Abstract

Hypertonic saline (HS) has been investigated as an immune modulator following hemorrhagic shock and sepsis. The neutrophil (PMN) response to HS is regulated by the release of ATP, which is converted to adenosine and activates adenosine receptors. Binding to A3 adenosine receptors promotes PMN activation and inhibition of A3 receptors improves the efficacy of HS resuscitation. A3 receptor expression of PMN has not been previously evaluated in injured patients.

Methods

Whole blood was obtained from 10 healthy volunteers and 60 injured patients within 2 hrs of injury. Inclusion criteria were blunt or penetrating injury with evidence of hypovolemic shock (SBP ≤ 90 mmHg and base deficit ≥6 mEq/L or need for blood transfusion); or evidence of severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) including initial Glasgow coma score (GCS) ≤ 8 or evidence of TBI on Head CT scan (Head AIS≥ 3) or intubation in the field or ED. A3 receptor expression was assessed by flow cytometry. PMN were also exposed to fMLP or HS (20-40 mM) in vitro. Clinical data was collected including admission physiology, injury severity (ISS scores), development of multiple organ failure, and survival.

Results

In normal volunteers, < 1% of PMN expressed A3 receptors on the cell surface. A3 receptor expression was significantly higher in injured patients and the level of expression correlated with the severity of injury (ISS ≥ 25: A3 positive PMN 36.6% vs. ISS <25: 16.2%; p=0.019) and degree of hypovolemic shock (SBP≤ 90: A3 positive PMN 43.8% vs. SBP>90: 20.6%; p=0.008). Stimulation with fMLP or HS increased A3 expression in normal volunteers, but only in patients with ISS< 25 or without hypovolemic shock.

Conclusion

A3 receptor expression on the surface of PMN is up-regulated by injury and increased expression levels are associated with greater injury severity and hypovolemic shock. Hypertonic saline increases A3 expression of PMN from healthy volunteers and less severely injured patients.

Keywords: adenosine A3 receptor, hypovolemic shock, neutrophil activation, hypertonic saline

Introduction

The polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) plays a key role in the inflammatory response, which occurs after severe traumatic injury or sepsis. Excessive PMN activation causes tissue injury due to the release of proteases and reactive oxygen species, which can lead to the development of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) in these critically ill patients (1). Recent studies have demonstrated that purinergic signaling through the release of ATP and autocrine feedback through adenosine receptors is a fundamental mechanism for neutrophil activation (2-4). PMNs express A2a receptors that lead to inhibition of neutrophil activation and A3 receptors that can lead to PMN activation when bound by adenosine (5).

Resuscitation with hypertonic saline is associated with improved survival and reduced inflammation in several animal models of hemorrhagic shock (6-8). However, recent clinical trials of hypertonic resuscitation following hypovolemic shock or severe traumatic brain injury have failed to demonstrate similar benefit in humans (9, 10). Thus a better understanding of the mechanisms of hypertonic modulation of the inflammatory response is needed. Recent work has demonstrated that hypertonic saline induces enhanced ATP release from PMNs that can result in PMN inhibition if A2a receptor expression predominates, but may exacerbate excessive PMN activation when A3 receptor expression is present (11-13). Furthermore, in a mouse model of sepsis, delayed resuscitation with HS actually increased A3 receptor expression and abolished the protective effects of hypertonic saline (11). This benefit was restored by the addition of an A3 receptor inhibitor (12). The expression of the PMN A3 receptor after injury in humans has not been previously studied. We hypothesized that severe injury would result in increased PMN A3 receptor expression, which may mitigate anti-inflammatory effects of hypertonic saline.

Methods

Patient Selection

Severely injured trauma patients were identified at the time of Emergency Department (ED) admission. Inclusion criteria were blunt or penetrating injury with evidence of hypovolemic shock based on an ED system blood pressure (SBP) ≤ 90 mmHg and a base deficit ≥6 mEq/L, the need for blood transfusion in the ED, evidence of severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) including initial GCS ≤ 8, evidence of TBI on Head CT scan (Head AIS≥ 3), or intubation in the field or ED. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 18 years of age. A group of ten healthy control donors was also recruited as a baseline comparison for A3 expression. Informed consent was obtained from the patient or their legal representative for continuation in the study as soon as feasible. The use of human subjects was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Washington.

Sample Collection

Whole blood (5 cc) was obtained by venipuncture from each patient within two hours of admission to the ED. Specimens for analysis were obtained from patients and controls using an evacuated tube collection system containing the anticoagulant sodium heparin (Vacutainer, Becton Dickinson, Rutherford, NJ). Samples were transported immediately to the laboratory for processing.

Clinical Data Collection

Prehospital and hospital data were collected for each patient including: demographics, mechanism of injury, injury severity using the AIS-98 injury severity score, vital signs and Glasgow Coma Score in the field and ED, initial routine laboratory results, and total fluids and blood products received in the first 24 hrs. Outcome parameters included survival to hospital discharge, development of multiple organ failure based on a non-neurological Marshall MODS score ≥ 6 (14, 15), which was assessed daily for duration of ICU duration after the initial 48 hrs after admission. Of these scores, the worst daily score was used for analysis in this report. In addition we monitored the development of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) based on a pO2/FiO2 ratio < 200 after 48 hrs of ICU admission, and durations of intensive care unit and hospital stays.

Assessment of Cell-Surface Adenosine Receptors on PMN

Multicolor extracellular staining and flow cytometric analysis of PMN A3 receptors were performed using 100-μL aliquots of fresh untreated whole blood, or whole blood treated with 20 mM HS, 40 mM HS, or 2 mM fMLP. The 40mM dose of HS represents the peak concentration observed with administration of the standard clinical dose of 250cc 7.5% saline in a 70kg adult. Samples were pipetted into 12 × 75 mm polystyrene Falcon tubes and incubated with saturating concentrations of anti-CD14-PerCP (BD Biosciences, San José, CA) and primary anti-human A3 adenosine receptor IgG antibodies that recognize extracellular portions of the receptor (Alpha Diagnostics, San Antonio, TX). After incubation for 30 min at 4°C in the dark, cells were centrifuged 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C and the cell pellet was resuspended in HBSS containing a 1:100 dilution of anti-IgG Alex 488 secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; final antibody concentration 1ug/ml). Samples were incubated for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. To prevent non-specific antibody binding, normal preimmune rabbit serum (Alpha Diagnostics, San Antonio, TX) was added to each tube prior to antibody exposure. Red blood cells were lysed by addition of 2 mL of FACS™ Lysing Solution. After 20 min at room temperature, cells were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 20°C. The supernatant was discarded and cells washed by centrifugation with HBSS . Then the cell pellet was re-suspended in 300 μL of 1% paraformaldehyde and cell staining was analyzed using a single-laser FACScan flow cytometer equipped with a 15-mW 488-nm air-cooled argon-ion laser (BD Biosciences). Instrument optical alignment, fluidics and day-to-day variability were monitored and adjusted using CaliBRITE® fluorescence beads and FACSComp® software. For each sample, 20,000 PMN events were collected at a flow rate of 500 events/sec using CellQuest® software, with a live gate set using FSC and SSC light-scatter profiles to distinguish PMN from other leukocytes. CD 14 staining was used to gate out the monocytes. Isotype-matched control antibodies were used to confirm specificity and to define quadrant markers for two-dimensional dot-plot and fluorescence histogram analysis of positive and negative cell populations. Subsequent data analysis was performed using FlowJo software v.8.8.6 (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR). Results are expressed as the frequency of marker-positive events PMN (% positive cells).

Statistical Analysis

Injury severity was stratified based on an injury severity score (ISS) greater than or equal to 25, hypotension in the field or ED (SBP≤90 mmHg), or arterial base deficit greater than or equal to 6 mEq/L. ANOVA was used to compare differences in the percentages of PMN expressing A3 receptors between groups. Differences were considered significant when P< 0.05.

Results

Ten healthy volunteers and 60 patients were enrolled between 1/25/2010 and 8/15/2010. The median age of the patient cohort was 40 yrs (IQR 26-57 yrs), 68% were male and 87% were victims of blunt trauma. The median ISS score was 29 (IQR 17-41) with 67% of patients having an ISS ≥ 25. Twenty-eight patients (47%) had hypotension in the ED (SBP ≤90 mmHg). Table 1 shows the patient demographics, initial physiology and injury severity. Mortality for this cohort was 12 patients (20%) with 22 patients (37%) meeting the criteria for ARDS and 6 patients (10%) developing multiple organ failure. Median length of hospital stay was 8 days (IQR 3-22 days) and median ICU stay was 3 days ( IQR 1-3 days).

Table 1.

Demographics, Initial physiology and Injury Severity, of the Patient Cohort, N=60

| Demographics | Median (IRQ) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Male Gender (% male) | 41 (68%) |

| Age >55 | 15 (25%) |

| Median Age (yrs) | 40 (26-57) |

|

| |

| Mechanism of Injury | |

|

| |

| Fall | 13 (22%) |

| MVC | 22 (37%) |

| MCC | 8 (13%) |

| Auto v-Pedestrian | 8 (13%) |

| GSW | 8 (13%) |

| Other | 1 (2%) |

|

| |

| Prehospital | |

|

| |

| First GCS | |

|

| |

| 3-8 | 27 (45%) |

| 9-13 | 7 (12%) |

| 14-15 | 12 (20%) |

|

| |

| Intravenous fluids (ml) | 1000 (0-1475) |

| Respiratory Rate | 24 (18-56) |

| PH Hypotension (SBP ≤90mmHg) | 30 (33%) |

| PH Bradycardia (HR<60 beats/min) | 9 (15%) |

| PH Tachycardia (HR>100beats/min) | 40 (67%) |

| Prehospital Intubation | 51 (85%) |

|

| |

| Emergency Department | |

|

| |

| ED Hypotension (SBP ≤90mmHg) | 28 (47%) |

| ED Tachycardia (HR>100beats/min) | 52 (87%) |

| ED Bradycardia (HR<60 beats/min) | 10 (17%) |

| ED Hypothermia (<36°C) | 32 (53%) |

| ED Acidosis (ABD ≥6 mmol/L) | 18 (30%) |

| ED Lactate ≥4mmol/L | 24 (40%) |

| ED Arrival Hgb <10g/dL | 20 (33%) |

| ED Coagulopathy (INR >1.4) | 7 (12%) |

|

| |

| Injury Severity Scores | |

|

| |

| AIS Head ≥3 | 34 (57%) |

| AIS Face ≥3 | 7 (12%) |

| AIS Chest ≥3 | 32 (53%) |

| AIS Abdomen ≥3 | 14 (23%) |

| AIS Extremity ≥3 | 14 (23%) |

| Max AIS ≥3 | 53 (88%) |

| ISS ≥25 | 40 (67%) |

| Median ISS | 29 (17-41) |

MVC= Motor Vehicle Crash, MCC= Motorcycle Crash, GSW= Gun Shot Wound, GCS= Glasgow Coma Score, PH= Prehospital, SBP= Systolic Blood Pressure , HR=heart rate, ABD= Arterial Base Deficit, Hgb= Hemoglobin, INR= International Normalized Ratio, AIS= Abbreviated Injury Score, ISS= Injury Severity Score

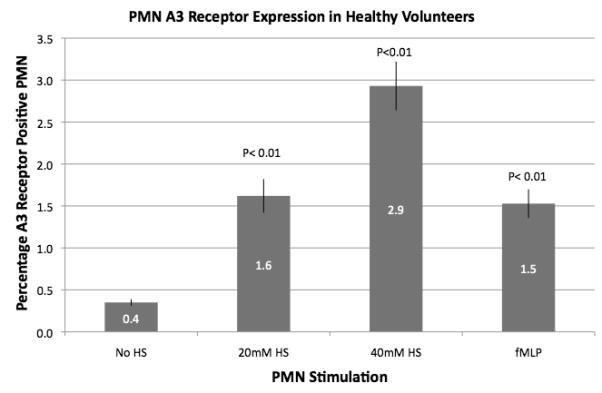

In whole blood from normal volunteers, <1.0% of peripheral PMN showed A3 receptor expression on the cell surface (Figure 1). There was a significant increase in A3 receptor expression upon in vitro exposure of cells with fMLP or hypertonic saline, but the resulting percentage of cells with A3 receptor expression even with stimulation was significantly lower than the expression in patient samples. Stimulated with 20 and 40 mM HS for 20 min increased the percentage of PMN expression A3 receptors from 0.4% to 1.6 and 2.9%, respectively. Stimulation of cells with 2 mM fMLP resulted in A3 expression of 1.5% of PMN. We found that lower concentrations of fMLP did not induce A3 receptor expression in whole blood.

Fig. 1.

Polymorphonuclear neutrophil A3 receptor expression in whole blood from healthy volunteers. Polymorphonuclear neutrophil A3 receptor expression was evaluated by flow cytometry on whole-blood samples obtained from healthy volunteers (n = 10). Baseline A3 receptor expression was very low and was significantly increased by in vitro exposure to HS (20 or 40 mM) or fMLP.

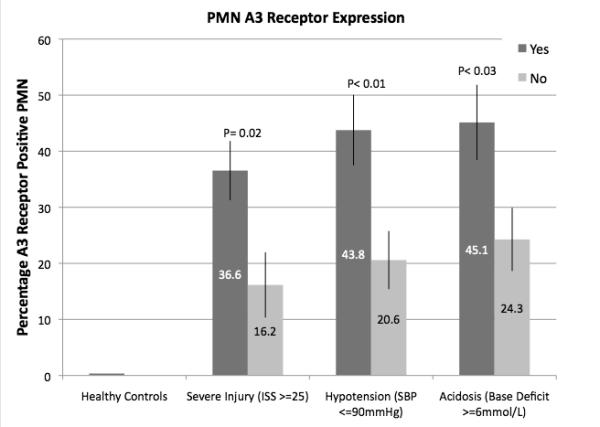

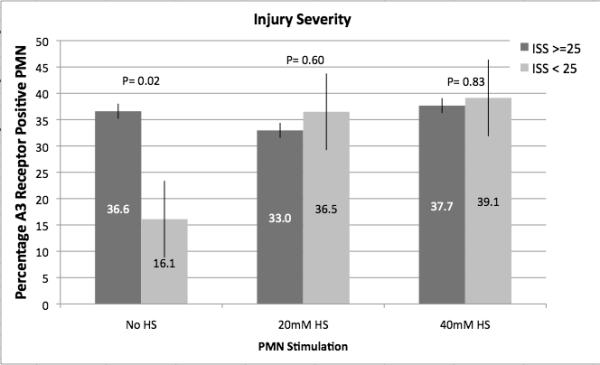

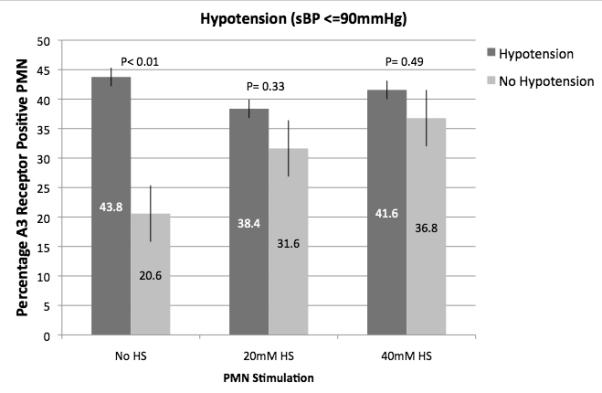

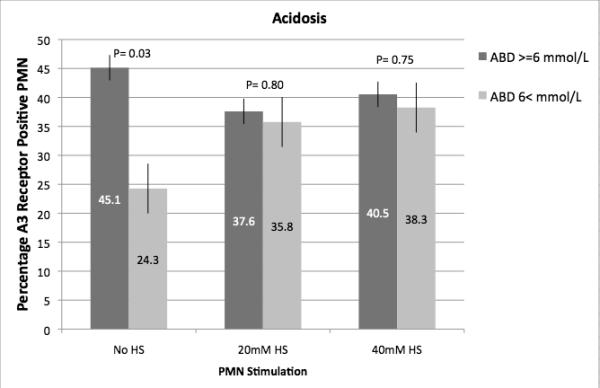

As illustrated in Figure 2, injured patients demonstrated much higher A3 expression than normal controls (46 to 130 fold higher) and this expression correlated with increased injury severity as defined by ISS > 25, hypotension in the field or ED (SBP < 90 mmHg) and metabolic acidosis in the ED as defined by a base deficit > 6 mEq/L. In vitro exposure of blood samples from trauma patients to hypertonic saline resulted in increased expression of A3 in the less severely injured, but no further increase was seen in samples from those patients with severe injuries, suggesting that no more that about 40-45%of PMN can be induced to express A3 receptors (Figure 3).

Fig. 2.

Polymorphonuclear neutrophil A3 receptor expression in injured patients. Polymorphonuclear neutrophil A3 receptor expression was evaluated by flow cytometry on whole-blood samples obtained from injured patients within 2 h of arrival in the ED (n = 60). Patients were stratified based on severity of injury (ISS score) or evidence of hypovolemic shock (SBP <90 mmHg or arterial base deficit ≥6 mM/L).

Fig. 3.

Effect of HS on A3 receptor expression from injured patients. Polymorphonuclear neutrophil A3 receptor expression was evaluated by flow cytometry on whole-blood samples obtained from injured patients within 2 h of arrival in the ED (n = 60). Samples were exposed to HS in vitro. Patients were stratified based on severity of injury (ISS score) or evidence of hypovolemic shock (SBP <90 mmHg or arterial base deficit ≥6 mM/L). A, Results based on stratification by the ISS score. B, Results based on stratification by hypovolemic shock (SBP ≤90 mmHg). C, Results based on stratification by metabolic acidosis (arterial base deficit ≥6 mM/L).

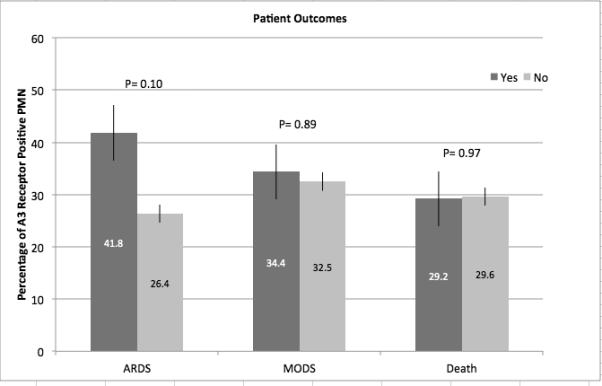

While we observed a relationship between A3 receptor expression and injury severity, we did not observe differences in A3 receptor expression between survivors and non-survivors or between patients who do or do not developed multiple organ failure (Figure 4). There was a trend toward higher A3 expression among patients who subsequently developed ARDS compared to patients who did not, but this difference did not reach statistical significance, possibly due to limited sample size as only 22 patients developed ARDS (p=0.096).

Fig. 4.

Relationship between A3 receptor expression and outcome in injured patients. Polymorphonuclear neutrophil A3 receptor expression was evaluated by flow cytometry on whole-blood samples obtained from injured patients within 2 h of arrival in the ED (n = 60). Patients were stratified based on mortality or the development of ARDS or MODS after injury.

Discussion

Patients with severe traumatic injury have an initial activation of the inflammatory response, which contributes to the development of late organ failure such as ARDS and MODS (1, 16). The PMN is considered a key regulator of this early response and thus understanding PMN activation in this setting is critical to defining immune-modulatory treatment strategies. Hypertonic saline has been proposed as one approach to modulate inflammation after injury and the validity of this approach is supported by preclinical studies in several animal models (6, 8, 17). Recent clinical trials, however, have failed to show benefit with regard to clinical outcome (9, 10, 18-20).

Our understanding of PMN activation has evolved over the past few years with increasing evidence pointing towards purinergic signaling through the release of ATP and autocrine feedback through nucleotide and adenosine receptors as a fundamental mechanism for PMN activation (2-4). ATP can also be released from damaged cells as a result of cell and tissue injury, which provides another source of adenosine that can regulate PMN activation. Hypertonic saline induces ATP release from PMNs, which can result in PMN inhibition if A2a receptor expression predominates, but HS may exacerbate excessive PMN activation when A3 receptor expression is present (11-13). Furthermore, hypertonic saline can lead to increased PMN A3 receptor expression under certain circumstances (5, 11).

This is the first study to evaluate A3 receptor expression in injured patients. We stratified patients based on their injury severity and evidence of hypovolemic shock. Our findings demonstrate that all injured patients have significantly higher A3 expression than cells from healthy volunteers and furthermore, patients with a high injury severity (ISS≥ 25) or evidence of hypovolemic shock exhibit the greatest A3 expression. Thus, the patients most likely to be treated with hypertonic saline resuscitation had the greatest expression of A3 receptors in response to their injuries. Exposure of whole blood from healthy volunteers and patients to hypertonic saline, in vitro, demonstrated further up-regulation of PMN A3 receptors in healthy volunteers and samples from patients with evidence of lower injury severity. It is possible that those patients with high injury severity or with hypovolemic shock are already expressing A3 receptors at a maximal level that cannot be further increased.

These studies have implications for our understanding of the effects of hypertonic resuscitation and suggest that desired immune-modulatory effects of HS in humans may require inhibition of A3 receptors. A recent study using hypertonic saline in a mouse model of sepsis suggested that use of an A3 receptor inhibitor could improve the immunomodulatory benefits of hypertonic saline. Further work needs to be done to clearly define the timing of these changes in receptor expression.

A limitation of our current study is that samples were available only up to 2 hours after hospital admission and, thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that A3 receptor expression may change during the early phase after injury. Thus we could not evaluate PMN activation and A3 receptor expression immediately after injury in the out-of-hospital setting when hypertonic saline would normally be administered. We know from our in vitro studies with PMNs from healthy volunteers that exposure of the cells to fMLP results in a rapid increase in A3 surface expression within the first 15 minutes (unpublished data, W. Junger) and thus it is likely that the response to injury may be equally rapid. Another limitation is that we were not able to measure the functional status of PMNs in the current study. However, previous studies have shown that PMNs from injured patients are activated, featuring increased CD11b expression as early as 1 hour after injury (21).

We also did not study the expression of the other major adenosine receptor of PMN, the A2a receptor, which suppresses PMN activation and thus may counteract the effects of A3 receptors. There is currently no commercial available antibody which recognizes the extracellular domain of the A2a receptor. The use of antibodies which recognize the intracellular domain would have been impossible as this approach would require permeabilization of the cells.. Finally, while we demonstrated a significant association between increased A3 receptor expression and severity of injury, we were unable to demonstrate any significant difference associated with patient outcomes. There was a trend toward higher A3 expression among patients who subsequently developed ARDS, but this did not reach statistical significance. It is likely that the sample size for this study limited our outcome analysis.

Hypertonic resuscitation has been of clinical interest for over 30 years and hyperosmotic treatment is commonly used to manage intracranial hypertension in patients with traumatic brain injury. Further studies are needed to continue to examine the mechanisms underlying post-injury inflammation in order to better define the therapeutic role of this approach following severe injury or sepsis.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lenz A, Franklin GA, Cheadle WG. Systemic inflammation after trauma. Injury. 2007;38:1336–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Junger WG. Purinergic regulation of neutrophil chemotaxis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2528–2540. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8095-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grassi F. Purinergic control of neutrophil activation. J Mol Cell Biol. 2010;2:176–177. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, et al. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314:1792–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Junger WG. Immune cell regulation by autocrine purinergic signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:201–212. doi: 10.1038/nri2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizoli SB, Kapus A, Fan J, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of hypertonic resuscitation on the development of lung inflammation following hemorrhagic shock. J Immunol. 1998;161:6288–6296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coimbra R, Hoyt DB, Junger WG, et al. Hypertonic saline resuscitation decreases susceptibility to sepsis after hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 1997;42:602–606. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199704000-00004. discussion 606-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angle N, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, et al. Hypertonic saline resuscitation diminishes lung injury by suppressing neutrophil activation after hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 1998;9:164–170. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199803000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bulger EM, May S, Brasel KJ, et al. Out-of-hospital hypertonic resuscitation following severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1455–1464. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulger EM, May S, Kerby JD, et al. Out-of-hospital Hypertonic Resuscitation After Traumatic Hypovolemic Shock: A Randomized, Placebo Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2011;253:431–441. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fcdb22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue Y, Chen Y, Pauzenberger R, et al. Hypertonic saline up-regulates A3 adenosine receptor expression of activated neutrophils and increases acute lung injury after sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2569–2575. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181841a91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue Y, Tanaka H, Sumi Y, et al. A3 adenosine receptor inhibition improves the efficacy of hypertonic saline resuscitation. Shock. 2011;35:178–183. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181f221fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Hashiguchi N, Yip L, et al. Hypertonic saline enhances neutrophil elastase release through activation of P2 and A3 receptors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00216.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzwater J, Purdue GF, Hunt JL, et al. The risk factors and time course of sepsis and organ dysfunction after burn trauma. J Trauma. 2003;54:959–966. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000029382.26295.AB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall JC, Cook DJ, Christou NV, et al. Multiple organ dysfunction score: a reliable descriptor of a complex clinical outcome. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1638–1652. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dewar D, Moore FA, Moore EE, et al. Postinjury multiple organ failure. Injury. 2009;40:912–918. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Junger WG, Coimbra R, Liu FC, et al. Hypertonic saline resuscitation: a tool to modulate immune function in trauma patients? Shock. 1997;8:235–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curry N, Hopewell S, Doree C, et al. The acute management of trauma hemorrhage: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2011;15:R92. doi: 10.1186/cc10096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulger E, Jurkovich G, Nathens A, et al. Hypertonic Resuscitation of Hypovolemic Shock after Blunt Trauma: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2008;143:139–148. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2007.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spruijt NE, Visser T, Leenen LP. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials exploring the effect of immunomodulative interventions on infection, organ failure, and mortality in trauma patients. Crit Care. 2010;14:R150. doi: 10.1186/cc9218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizoli SB, Rhind SG, Shek PN, et al. The immunomodulatory effects of hypertonic saline resuscitation in patients sustaining traumatic hemorrhagic shock: a randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial. Ann Surg. 2006;243:47–57. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000193608.93127.b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]