Abstract

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (EGFR), a receptor tyrosine kinase, is commonly altered in different tumor types leading to abnormally regulated kinase activity and excessive activation of downstream signaling cascades including cell proliferation, differentiation and migration. To investigate the EGFR signaling events in real time and in living cells and animals, we here describe a multidomain chimeric reporter whose bioluminescence can be used as a surrogate for EGFR kinase activity. This luciferase-based reporter was developed in squamous cell carcinoma cells (UMSCC-1) to generate a cancer therapy model for imaging EGFR. The reporter is designed to act as a phosphorylated substrate of EGFR and reconstitutes luciferase activity when it is not phosphorylated, thus providing a robust indication of EGFR inhibition. We validated the reporter in vitro and demonstrated that its activity could be differentially modulated by EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibition with erlotonib or receptor activation with EGF. Further experiments in vivo demonstrated quantitative and dynamic monitoring of EGFR tyrosine kinase activity in xenograft. Results obtained from these studies provide unique insight into pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of agents that modulate EGFR activity, revealing the usefulness of this reporter in evaluating drug availability and cell targeting in both living cells and mouse models.

Keywords: EGFR, EPS-15, Molecular Imaging, Split Luciferase, Reporter

Introduction

The emerging fields of genomics and proteomics have led to a better comprehension of the pathophysiology of cancer and the identification of novel signaling pathways. These pathways offer novel targets which has led to the development of lead molecules designed to inhibit the signaling derived from these pathways. However, this knowledge has provided considerable challenges for translating in vitro findings to in vivo cancer biology. Molecular imaging technologies have the potential to address these scientific challenges and to bridge the gap between in vitro drug discovery and in vivo target inhibition [1].

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is an established therapeutic target in oncology. Nearly 90% of all head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cases exhibit an enhanced expression of EGFR which leads to constitutive activation of the receptor and therefore correlates with tumor proliferation, metastasis, resistance to conventional therapy [2]. Furthermore, the over expression of EGFR has also been detected in many epithelial malignancies including cancers of bladder, breast, lung, brain, stomach, prostate, ovary and pancreas [3].

EGFR a 170 kDa transmembrane glycoprotein, belongs to the Erb/HER family of transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinases and is comprised of an extracellular ligand binding domain (621 amino acids) and an intracellular protein tyrosine kinase domain (542 amino acids) connected by a small transmembrane-anchoring region (23 amino acids) [4]. The binding of a ligand, such as EGF, causes the EGFR to dimerize with itself or with another member of ErbB family of receptors, leading to receptor-linked tyrosine activation and the activation of downstream signaling cascades including cell proliferation, differentiation, migration and adhesion. Studies by Lamaze and Schmid (1995) demonstrated the importance of kinase substrates for the efficient activation of EGFR signaling, and the epidermal growth factor substrate 15 (EPS15) is required for the efficient activation of EGFR [5]. Epidermal growth factor substrate 15 (EPS15) has been identified as one downstream signaling protein [6] that can be phosphorylated on Tyr850 residue following EGFR activation [7]. The EGFR signaling pathway is considered a key determinant of biologic aggressiveness of tumors, and a major target for novel anti-cancer therapies. Inhibition of this receptor with small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors or receptor specific antibodies has proven to be an effective therapeutic strategy in multiple cancer sites [8].

Although EGFR activity can be measured using standard molecular biology techniques in vitro, assessing EGFR inhibition in real time in animals has not been previously feasible. We reasoned that developing a method to image EGFR activity in animals would be a valuable tool to further understand the biology of in vivo EGFR inhibition. To this end we constructed the EGFR kinase reporter (EKR), a multi-domain chimeric protein that coordinately regulates luciferase activity based on both the concept of luciferase complementation [9] and reversible phosphorylation of the relatively specific EPS15 tyrosine phosphorylation site [10-11]. We demonstrate that EKR, but not the phenylalanine mutated control vector, is activated by micromolar concentrations of erlotonib and results in bioluminescence in living cells providing a molecular reporter that we use to quantify in vitro EGFR activity as well as in vivo inhibition of EGFR by erlotonib.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Chemicals

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to phospho-EGFR (Y845), Met (pYpYpY1230/1234/1235), GAPDH and mouse polyclonal Met antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to EGFR and firefly luciferase were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and Chemicon (Millipore, Billerica, MA), respectively. Mouse monoclonal antibodies to p-Tyrosine were purchased from Zymed (Carlsbad, CA). SU11274, an inhibitor of c-Met, was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Epidermal growth factors (EGFs) and Luciferin were purchased from Invitrogen and Biosynth (Naperville, IL) respectively. Erlotinib was gifted by Genentech (San Francisco, California).

Plasmid Construction

The EKR Reporter was generated in the mammalian expression vector pEF. Construction of the EKR luciferase reporter was based upon the split luciferase design of Luker et al., 2004. The N-terminal domain (NLuc) was PCR-amplified using primers that generated a product comprising a SalI restriction site followed by a Kozak consensus sequence and a NotI restriction site at the 3’ end. The C-terminal firefly luciferase domain (C-Luc) was amplified using primers that produce a 5’ XbaI site followed by the EPS15 substrate sequence (corresponding to amino acids 843-858) flanked by the linker GSHSGSGKP on each side, with a 3’ EcoRI restriction site after the termination codon. The SH2 domain was amplified from the mouse p52 Shc domain with insertion of a 5’ NotI site and a 3’ XbaI site for cloning. The EKR-mut reporter was constructed by mutagenesis of the EPS15 tyrosine phosphorylation site (Y850) to alanine using the Quick Change kit (Stratagene). All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing.

Cell Culture and Transfection

The head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell line, UMSCC1, was grown in RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Complete medium was supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 100 units/mL penicillin/streptomycin. Cell cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. To construct stable cell lines, the EKR reporter plasmids (wild type and mutant) were stably transfected into UMSCC1 cells using Fugene (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and stable clones were selected with 500μg/mL G418 (Invitrogen). Resulting clones were isolated and cultured for further analysis by western blot for determination of expression levels of the recombinant protein.

Western Blots and Immunoprecipitation

UMSCC1-EKR cells in culture dishes were collected and centrifuged at 1,800×g for 5 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were washed twice with cold PBS and then lysed with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris•HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM NaF, and 1 mM Na3VO4 and supplemented with complete protease inhibitors mixture (Roche Diagnostics). Cells in lysis buffer were rocked at 4°C for 30 min. The lysates were then cleared by centrifugation. Protein content was determined by a detergent-compatible protein assay kit from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Lysates with equal amounts of protein were separated by Laemmli SDS/PAGE, and the levels of protein expression were detected by western blot analysis with anti-EGFR (1:1000), p-EGFR (1:1000), MET (1:500), p-MET (1:1000), Luciferase (1:5000), p-tyrosine (1:1000) and GAPDH (1:1000) using the Enhanced Chemi-luminescence (ECL) Western Blotting System (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). For immunoprecipitation, cell supernatant extracts (2000μg) were incubated with the luciferase antibody for 1 hour. Immune complexes were captured using protein G–Sepharose (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and washed three times using RIPA buffer. The resulting pellet was boiled for five minutes in sample buffer (4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.004% bromophenol blue, 0.125M tris-HCL, pH 6.8) and resolved by SDS/PAGE.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfections

UMSCC1-EKR-WT cells were plated onto 6-well plates at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/ml and incubated for 24 hr in culture medium. The cells were then transfected with siRNAs specific to EGFR (J-003114-11 or J-003114-11 from Dharmacon) or non-targeting siRNA (D-001210-01, Dharmacon). siRNA transfection was carried out using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were analyzed 68 hr later for bioluminescence imaging followed by Western blot.

In Vitro and In Vivo Bioluminescence Imaging

Live cell bioluminescence imaging was performed using the IVIS imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA). D-luciferin (100μg/mL final concentration) was added to the growth medium prior to imaging and photon counts were acquired after 10 minute incubation at 37°C. An exposure time of one minute was used for acquisition. Living Image 3.0 software was used for data analysis (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA). For in Vivo experiments, UMSSC1-EKR cells (1.0 ×106) were inoculated into the flanks of nu/nu CD-1 nude mice (Charles River Laboratory) and grown for 10 days. When tumors reached approximately 100mm3 in volume, mice were randomized into two groups and treatment was initiated. Erlotinib was prepared in 1% Tween 80 and delivered at a dose of 100mg/kg by oral gavage. Control animals were treated with vehicle only. For in vivo bioluminescence, mice were anesthetized using a 2% isofluorane/air mixture and injected with a single dose of 100mg/kg D-luciferin in phosphate buffered saline intraperitoneally. Image acquisition was initiated 5 minutes following injection of luciferin. Serial bioluminescence images were acquired prior to erlotonib/vehicle treatment and at 3, 6, 12, and 24 hour time intervals afterwards.

Data Analysis

Percent changes in signal intensity were calculated using pretreatment values as baseline and plotted as means ± SEM for each of the groups. Statistical comparisons were made by using the unpaired Student’s t test with a value of p< 0.05 considered to be significant.

Results

Construction and validation of a bioluminescent EGFR Kinase Reporter

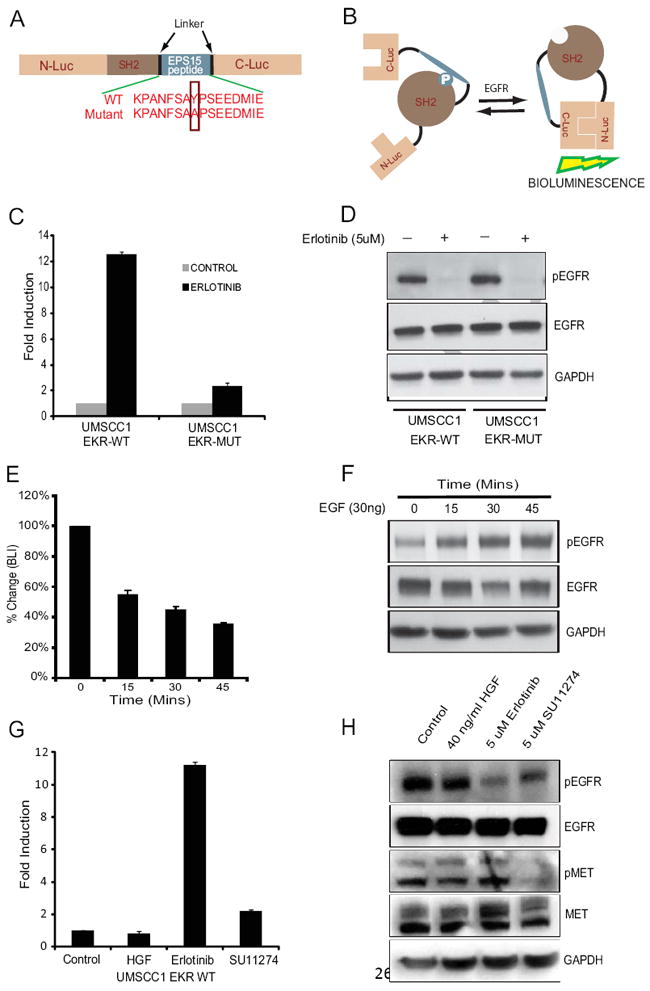

The EGFR kinase reporter (EKR) is a split luciferase vector mechanistically similar to a previously developed method to detect Akt and FADD kinases activity [11-12]. The reporter encodes a polypeptide with four functional domains (Fig. 1A): the N-and C-terminal are composed of luciferase amino acids 2-416 (N-luc) and amino acids 398-550 (C-luc), respectively, and flank the SH2 domain from mouse p52 Shc (amino acids 374-465) and the tyrosine phosphorylation sequence of EPS15 (Y850). EPS15 has previously been demonstrated to be specifically phosphorylated by activated EGFR [10] and its phosphorylation is highly regulated in cancer cell lines [7]. A phenylalanine mutation of the corresponding Y850 EPS15 phosphorylation site was also generated by site directed mutagenesis as a control vector for imaging experiments (EKR-Mut). The reporter’s design predicts that in the absence of EPS15 Y850 phosphorylation the N-and C- terminal luciferase domains interact and reconstitute enzyme activity, but that active phosphorylation of the EPS15 sequence promotes intra-molecular association with the SH2 domain and prevents functional interactions between the N- and C-terminal luciferase domains (Fig. 1B). Thus, the reporter is designed to increase bioluminescent activity following inhibition of the EPS15 peptide phosphorylation.

Fig 1. Bioluminescence EGFR Kinase Reporter (EKR).

(A) Diagrammatic representation of the EKR domain structure. N-Luc and C-Luc are the N- and C-terminal domains of firefly luciferase, respectively, and flank tandem SH2 domain and EPS15 sequences. Two versions of the EKR were developed: the EKR, which contains the wildtype EPS15 peptide sequence and the EKR-Mut, which contains an Y850A substitution and removes the EGFR phosphorylation site. (B) Schematic illustration demonstrating the basis of EKR activity. Phosphorylation of the EPS15 peptide at Y850 results in interaction with SH2 phosphopeptide binding domain causing steric constraints on C-luc and N-Luc association. Inhibition of Y850 phosphorylation results in decreased binding of the phosphopeptide to the SH2 domain and enables N-Luc and C-Luc to interact, producing bioluminescence. (C) UMSCC1-EKR-WT cells as well as UMSCC1-EKR-Mut cells were treated with 5uM erlotinib for 3 hours. The changes in bioluminescence activity over control vehicle treated levels were determined and reported as fold induction. (D) Cells from (C) were collected and lysed for western blotting analysis with antibodies for phospho-EGFR or total EGFR. GAPDH antibody was used as a loading control. (E) UMSCC1-EKR-WT cells were serum-starved overnight, treated with 30 ng/ml of EGF and imaged at various times (15, 30 and 45 mins). The changes in BLI activity compared with pretreatment value were expressed as percentage change. (F) Cells from (E) were analyzed by western blotting using antibodies specific for phospho-EGFR, total EGFR or GAPDH as a control. (G) UMSCC1-EKR-WT cells were treated with 40ng/ml HGF for 30 mins, 5uM erlotinib and 5uM c-MET inhibitor SU11274 for 3 hours. The changes in bioluminescence activity over control vehicle treated levels were determined and reported as fold induction. (H) Cells from (G) were analyzed by western blotting using antibodies specific for phospho-EGFR, total EGFR, phospho-MET, total MET or GAPDH as a control.

We hypothesized that the EKR would be a sensitive molecular reporter for EGFR kinase activity. Since EGFR is overexpressed in UMSCC1 squamous cell carcinoma cell line [13], we generated stable UMSCC1 cell lines expressing the EKR-WT, EKR-Mut, or luciferase. Treatment of UMSCC1-EKR-WT cells with an EGFR inhibitor, Erlotinib resulted in a 10-fold induction in bioluminescence activity compared to control DMSO treated cells. In contrast, UMSCC1-EKR-Mut cells showed no significant change in bioluminescence activity in response to Erlotinib treatment (Fig. 1C). Western blot analysis with either stable cell line upon Erlotinib treatment revealed a decrease in phospho-EGFR levels, but not total EGFR levels (Fig. 1D).

To explore if the EKR was able to sense activation of EGFR kinase activity (rather than inhibition), we also examined the effects of epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulation on EKR bioluminescent activity. UMSCC-1-EKR-WT cells were serum starved overnight and treated with 30ng/ml of EGF. Our results demonstrated a significant reduction (55 +/- 3% SD) of luciferase activity after 45 mins of EGF treatment (Fig. 1E). Western blot analysis of EGFR phosphorylation confirmed that reductions in luciferase activity corresponded to the observed increase in EGFR phosphorylation over this time period (Fig. 1F). To investigate the specificity of the reporter for EGFR, the EKR-WT reporter-expressing cells were treated with another receptor tyrosine kinase c-MET inhibitor SU11274 and EGFR inhibitor erlotinib for 3 hours. Also reporter cells serum starved overnight and treated with and c-MET receptor ligands hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF) for 30 mins. Bioluminescence activity measurements revealed a 10-fold increase after erlotinib treatment while c-met inhibitor and ligands did not show any significant change in bioluminescence activity (Fig. 1G). Western blot analysis of the SU11274 and erlotinib-treated cells revealed a decrease in phosphorylation of c-MET and EGFR respectively, whereas no change in levels of total c-MET and EGFR was observed (Fig. 1H). Together, the in vitro results demonstrate that enhancement or reduction of EKR luciferase activity depends upon EGFR activity. Because EGFR is activated in UMSCC1 cells under normal culture conditions, expression of the reporter in this cell line provides increased sensitivity and a quantitatively higher signal range to measure EGFR inhibition.

EKR detects EGFR inhibition in vitro

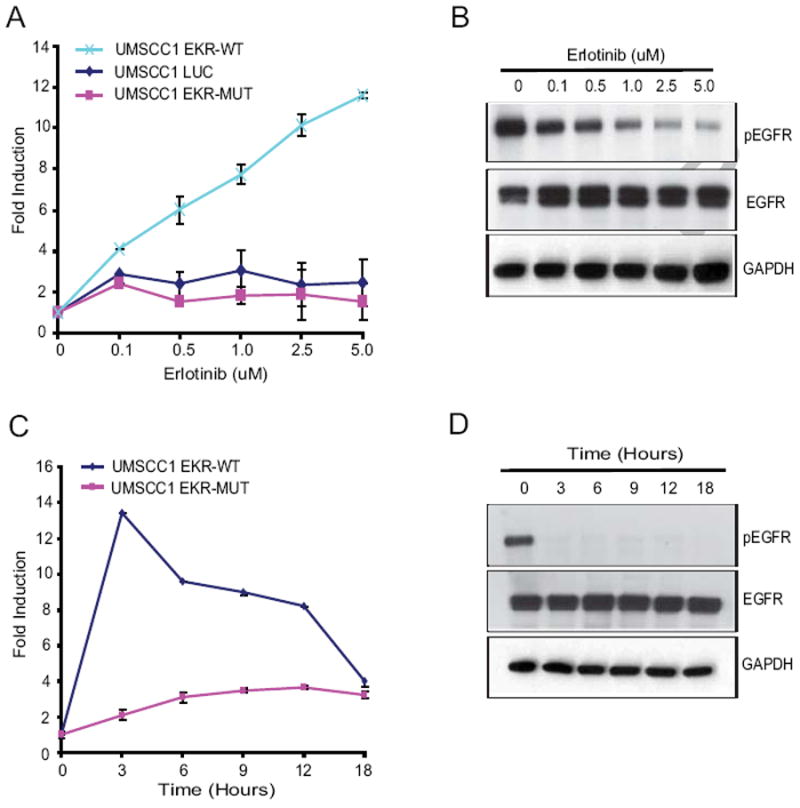

Live cell imaging experiments were performed to demonstrate dose-dependent kinetics for enhanced bioluminescence in EKR expressing cells after EGFR inhibition with a small molecule inhibitor of EGFR, Erlotonib (Fig. 2A) without significant changes in bioluminescent activity in EKR-Mut or Luc expressing cells. Bioluminescence in EKR expressing cells was maximally induced 13.2 +/- 0.9 fold over untreated controls by 5uM erlotonib. Western blot analysis of EGFR phosphorylation confirmed that the dose-dependent enhancement in luciferase activity corresponded directly to a decrease in EGFR phosphorylation (Fig. 2B). Time course experiments were also performed and demonstrated peak luminescence at approximately 3 hrs after erlotonib addition with sustained luciferase activity for up to 12 hours (Fig. 2C). These results demonstrate that the EKR reporter functions like a molecular switch that quantitatively measures EGFR tyrosine kinase activity using biologically relevant concentrations of erlotonib.

Fig 2. Imaging EGFR activity in vitro.

(A and B) Dose-dependent imaging of EGFR activity. UMSCC-EKR (WT and Mut) stable cells were treated with various doses (0.1μM, 0.5μM, 1μM, 2.5μM and 5μM) of erlotinib, an EGFR inhibitor, and BLI activity at 3 hours was analyzed and expressed as fold induction. Data were derived from a minimum of three independent experiments. Cell lysates were collected for western blot analysis using phospho-EGFR and total EGFR antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C and D) Time-dependent imaging of EGFR activity. UMSCC-EKR (WT and Mut) stable cells were treated with 5uM erlotinib at different time points (0, 3, 6, 9, 12 and 18 hours) and BLI activity was measured at the indicated time points. Lysates prepared from similarly treated cells were subjected to western blotting using antibodies as indicated.

Although the EKR bioluminescence was less robust at 6 hours, western blots demonstrated that EGFR phosphorylation was completely eliminated throughout this time period, suggesting that reporter activation is attenuated over time (Fig. 2D). To further investigate the time-dependence of EKR reporter activation we examined the effects of antibody-mediated EGFR inhibition, a kinetically slower process that occurs over several hours and requires both receptor endocytosis and down regulation [14]. Consistent with our previous findings, EGFR inhibition with Cetuximab did not activate the EKR reporter (data not shown) confirming that reporter sensitivity in UMSCC1 cells is maximal at early time points and is reduced with prolonged EGFR inhibition. In summary, our data demonstrate that the EKR reporter detects short term, dynamic EGFR inhibition (~12 hours) in living cells that overexpress the EGFR.

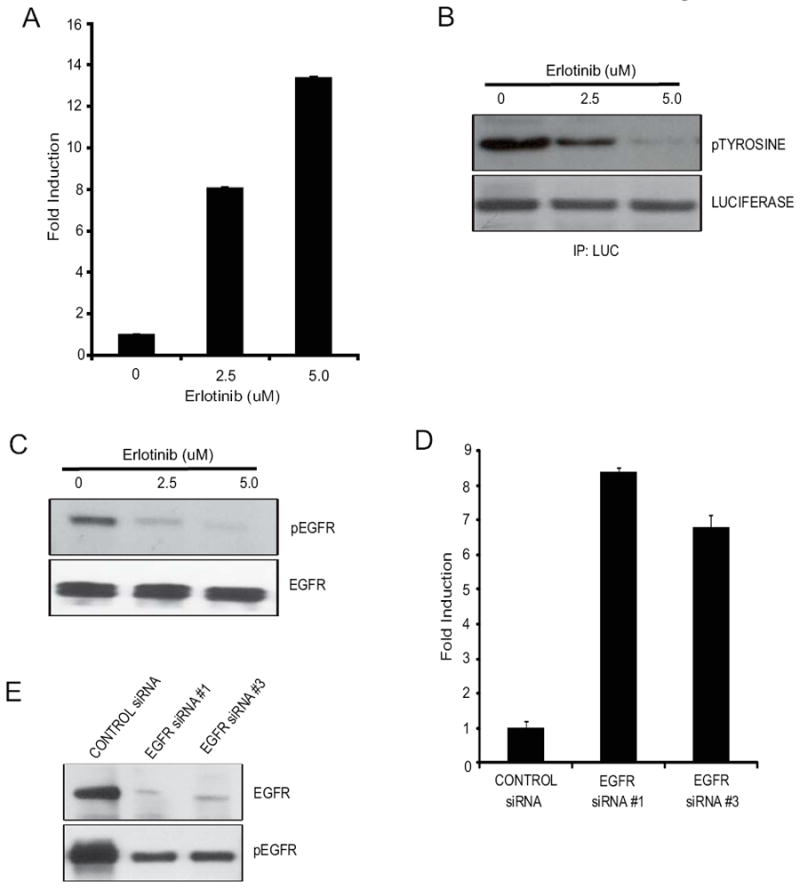

EKR is a substrate for EGFR tyrosine kinase

Since EKR function was predicated on it being phosphorylated in an EGFR-dependant manner, we treated UMSCC1-EKR-WT cells with erlotinib (2.5 uM and 5.0 uM) and observed an approximately 12-fold increase in bioluminescence with 5.0 uM of erlotinib (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, immunoprecipitation of EKR from these cells using a luciferase specific antibody followed by western blot analysis using a phospho-tyrosine antibody revealed a decrease in tyrosine phosphorylation of EKR in response to Erlotinib treatment (Fig. 3B). Inhibition of EGFR in treated but not control cells was also observed upon western blot analysis of cell extracts using antibodies specific for total EGFR and phospho-EGFR (Fig. 3C). The results confirm that EKR bioluminescence is dependent on EGFR tyrosine kinase activity through downstream phosphorylation of the reporter. Additional proof that EKR is a specific indicator for EGFR activity was obtained from experiments in which EGFR was inhibited in response to siRNA-mediated down-regulation of the receptor. Targeted down-regulation of EGFR expression resulted in a 7-fold induction of the bioluminescence activity compared to a control non-silencing siRNA in UMSCC1-EKR-WT cells (Fig. 3D). This result was consistent with a substantial decrease in levels of total EGFR and phosphorylated EGFR as determined by western blotting analysis (Fig. 3E).

Fig 3. EKR is a substrate for EGFR tyrosine kinase activity.

(A) UMSCC1-EKR-WT cells treated with erlotinib (2.5μM and 5μM) for 3 hours. Increase in bioluminescence activity of EKR reporter molecule was monitored and the data is plotted as fold induction over control and +/- SEM. (B) Luciferase specific antibody was used to immunoprecipitate the EKR reporter molecule and western blot analysis is performed by using phospho-tyrosine antibody, as well as luciferase specific antibody as control. (C) Cells from (A) were also collected and lysed for western blotting analysis with antibodies for phospho-EGFR or total EGFR.(D) UMSCC1-EKR-WT cells were transfected with 2 different EGFR siRNAs (EGFR siRNA#1 & siRNA#3) or scrambled siRNA, and bioluminescence activity was monitored after 68 hours. Changes in bioluminescence activity were plotted as fold induction using scrambled siRNA treatment level as baseline. (E) Cell lysates from (D) were collected and analyzed by western blotting analysis using antibodies specific for phospho-EGFR and total EGFR.

EKR In Vivo Imaging

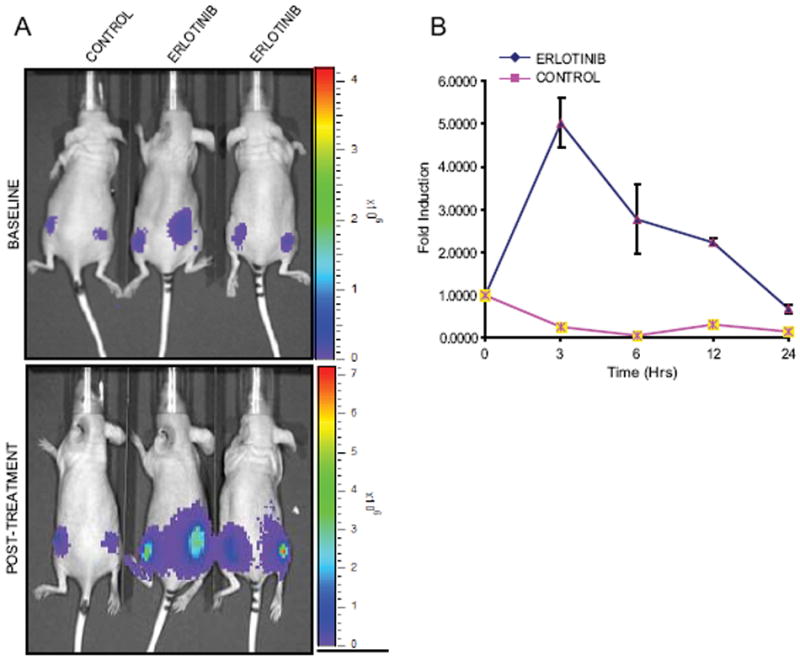

The EKR reporter efficiently detects EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibition by in vitro, and we therefore hypothesized that this reporter could be further developed into a model system to measure changes in EGFR activity in vivo. To test this concept, nude mice with established bilateral UMSCC1-EKR flank xenografts were given oral gavages of either 100mg/kg erlotinib or vehicle alone (Fig. 4A). Serial imaging was performed 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 hours following drug administration and compared to pretreatment bioluminescence. Results demonstrate that erlotonib significantly activated the EKR reporter 5.0 (+/- 0.58) fold with maximal activation 3 hours after treatment and significant activation for up to 6 hours (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that the EKR reporter is a novel molecular tool to measure EGFR inhibition in vivo.

Fig 4. Imaging of EGFR activity in vivo.

(A and B) UMSCC1-EKR stable cells were implanted subcutaneously into nude mice. BLI activity was monitored in mice after 4 weeks when tumors reached about 40-60mm3 size. BLI activity of pretreated and treated with vehicle control (20% DMSO in PBS) and erlotinib (100mg/kg) was monitored at various times. Fold induction of signal intensity were calculated using pretreatment values as baseline and plotted as means ± SEM for each of the groups.

Discussion

Quantitating tumor therapeutic response to anti-cancer therapies in vivo is often complicated by cell death and signal loss secondary to the intrinsic cytotoxicity of the treatment. Using FRET-based reporter studies from literature, we have constructed a reporter molecule, EKR, which we describe here, based on the split-luciferase technology [9,11,12]. We found that inhibition of EGFR kinase activity resulted in activation of reporter’s bioluminescence activity. Immunoprecipitation of the reporter followed by analysis of phospho-tyrosine content showed that the reporter was phosphorylated in EGFR-dependent manner. Our results demonstrated that the EKR reporter can detect short term, dynamic EGFR inhibition (~12 hours) in living cells that overexpress the EGFR. Notably, stimulation of UMSCC1-EKR (WT) cells with EGF resulted in increased levels of EGFR phosphorylation, which was consistent with the reductions in luciferase activity. Additionally, the EKR reporter also served as a novel molecular tool to measure EGFR inhibition in vivo.

The EKR reporter is unique in that it provides a gain of function for luciferase activity and has the advantage of maintaining a quantifiable signal in the context of successful therapeutic intervention. Practically, the EKR gain of function design allows for signal measurement under conditions of tumor regression and dynamic assessment of target activity under these conditions. The second advantage of the EKR design is its ability to preferentially detect EGFR inhibition instead of activation. This function enables rapid assessment of pharmacologic variables related to drug availability. For example, bioavailability of orally administered EGFR inhibitors can be determined immediately and sequentially to optimize therapeutic routes of drug administration. Small molecule EGFR inhibitors currently in clinical use have been shown to be limited by an inability to cross the blood brain barrier [15-16]. Integration of the EKR reporter into a CNS tumor model system could thus provide a rapid and non-invasive method for assessing target inhibition in the brain and be useful for drug discovery in this context.

Several strategies to measure ErbB family receptor function using luciferase or beta galactosidase reporters have been developed [17-19]. Wehrman et al., generated fusion proteins for EGFR, ErbB2, and ErbB3 that contained the extracellular and transmembrane RTK domains fused to weakly complementing B-galactosidase deletion mutants [17, 20]. In this two construct system, receptor activation results in enhanced galactosidase activity that can be measured using a fluorescent substrate and FACS analysis. Botvinnik et al., (2010) generated ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4 tobacco etch virus (TEV) constructs by fusing complementing fragments of the TEV protease to the c-terminal end of the respective receptors [21]. Ligand induced activation of receptors thus results in protease activity and release of a transcription factor that drives luciferase expression on a third co-transfected construct. Li et al., (2008) used luciferase complementation by fusing N- and C-terminal luciferase domains to EGFR and signaling partners Grb and Shc to demonstrate receptor activation through reconstitution of luciferase activity both in vitro and in vivo, although receptor dimerization could not be demonstrated with this system [19]. Yang et al., (2009) used luciferase complementation imaging to follow EGF-induced conformational changes in its receptor in real time in live cells. Their data demonstrated the utility of the luciferase system for in vivo imaging changes in EGF receptor dimerization and confirmation [22]. Each of these imaging strategies can demonstrate ErbB receptor activity after ligand stimulation, and each also provides subtly different information. B-Gal complementation reflects extracellular domain dimerization, TEV complementation reflects full length receptor dimerization, and the luciferase complementation strategy measured interactions with downstream signaling partners. However, each of these strategies also alters the EGFR by either truncation of the receptor or alteration/addition to the amino acid coding sequence, and thus the EKR may have the additional advantage of reporting the function of unmodified, wild type EGFR in cancer cell signaling.

There are advantages and disadvantages to each design for measuring ErbB receptor signaling, and the EKR reporter, while displaying dynamic activation, is limited by time and undergoes signal attenuation. The EKR is therefore not optimal for measuring prolonged or delayed EGFR inhibition, and furthermore it is not optimal for measuring EGFR activation by either ligand or radiation. Regardless, the simplicity, robust performance, and unique gain of function design demonstrate the utility of the EKR reporter as a molecular tool to measure EGFR activity both in vitro and in vivo.

In summary, we have demonstrated the ability to image EGFR inhibition both in vitro and in vivo using a multi-domain chimeric reporter vector. This technique for molecular imaging of pharmacologic EGFR inhibition complements existing EGFR reporter designs and preferentially measures target inhibition. The EKR thus provides a simple method for evaluating drug bioavailability and cell targeting in both living cells and mouse models and has the potential advantage of not interfering with or artificially modulating the function of the wild type receptor.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health research grants R01CA129623 (AR), R21CA131859 (AR), U24CA083099 (BDR) P50CA093990 (BDR).

Abbreviations used

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- EKR

EGFR kinase reporter

- EPS15

Epidermal growth factor substrate 15

- HNSCC

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- BLI

Bioluminescence imaging

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chenevert TL, Stegman LD, Taylor JM, Robertson PL, Greenberg HS, Rehemtulla A, Ross BD. Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging: an early surrogate marker of therapeutic efficacy in brain tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:2029–2036. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.24.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grandis JR, Tweardy DJ. TGF-alpha and EGFR in head and neck cancer. J Cell Biochem. 1993;17:188–191. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240531027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salomon DS, Brandt R, Ciardiello F, Normanno N. Epidermal growth factor-related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1995;19:183–232. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(94)00144-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gullick WJ, Downward J, Waterfield MD. Antibodies to the autophosphorylation sites of the epidermal growth factor receptor protein-tyrosine kinase as probes of structure and function. EMBO J. 1985;(4):2869–2877. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamaze C, Schmid SL. Recruitment of epidermal growth factor receptors into coated pits requires their activated tyrosine kinase. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:47–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fazioli F, Minichiello L, Matoskova B, Wong WT, Di Fiore PP. eps15, a novel tyrosine kinase substrate, exhibits transforming activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5814–5828. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Confalonieri S, Salcini AE, Puri C, Tacchetti C, Di Fiore PP. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Eps15 is required for ligand-regulated, but not constitutive, endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:905–912. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.4.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonner JA, De Los Santos J, Waksal HW, Needle MN, Trummel HQ, Raisch KP. Epidermal growth factor receptor as a therapeutic target in head and neck cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2002;12:11–20. doi: 10.1053/srao.2002.34864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luker KE, Smith MC, Luker GD, Gammon ST, Piwnica-Worms H, Piwnica-Worms D. Kinetics of regulated protein-protein interactions revealed with firefly luciferase complementation imaging in cells and living animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12288–12293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404041101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torrisi MR, Lotti LV, Belleudi F, Gradini R, Salcini AE, Confalonieri S, Pelicci PG, Di Fiore PP. Eps15 is recruited to the plasma membrane upon epidermal growth factor receptor activation and localizes to components of the endocytic pathway during receptor internalization. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:417–434. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.2.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Lee KC, Bhojani MS, Khan AP, Shilman A, Holland EC, Ross BD, Rehemtulla A. Molecular imaging of Akt kinase activity. Nat Med. 2007;13:1114–1119. doi: 10.1038/nm1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan AP, Schinske KA, Nyati S, Bhojani MS, Ross BD, Rehemtulla A. High-throughput molecular imaging for the identification of FADD kinase inhibitors. J Biomol Screen. 2010;15:1063–1070. doi: 10.1177/1087057110380570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng FY, Lopez CA, Normolle DP, Varambally S, Li X, Chun PY, Davis MA, Lawrence TS, Nyati MK. Effect of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor class in the treatment of head and neck cancer with concurrent radiochemotherapy in vivo, Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:2512–2518. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grünwald V, Hidalgo M. Developing inhibitors of the epidermal growth factor receptor for cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:851–867. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.12.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haas-Kogan DA, Prados MD, Lamborn KR, Tihan T, Berger MS, Stokoe D. Biomarkers to predict response to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1369–1372. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.10.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakravarti A, Chakladar A, Delaney MA, Latham DE, Loeffler JS. The epidermal growth factor receptor pathway mediates resistance to sequential administration of radiation and chemotherapy in primary human glioblastoma cells in a RAS-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4307–4315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wehrman TS, Raab WJ, Casipit CL, Doyonnas R, Pomerantz JH, Blau HM. A system for quantifying dynamic protein interactions defines a role for Herceptin in modulating ErbB2 interactions, Proc. Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19063–19068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605218103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wehr MC, Laage R, Bolz U, Fischer TM, Grünewald S, Scheek S, Bach A, Nave KA, Rossner MJ. Monitoring regulated protein-protein interactions using split TEV. Nat Methods. 2006;3:985–993. doi: 10.1038/nmeth967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W, Li F, Huang Q, Frederick B, Bao S, Li CY. Noninvasive imaging and quantification of epidermal growth factor receptor kinase activation in vivo. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4990–4997. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blakely BT, Rossi FM, Tillotson B, Palmer M, Estelles A, Blau HM. Epidermal growth factor receptor dimerization monitored in live cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:218–222. doi: 10.1038/72686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Botvinnik A, Wichert SP, Fischer TM, Rossner MJ. Integrated analysis of receptor activation and downstream signaling with EXTassays. Nat Methods. 2010;7:74–80. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang KS, Ilagan MX, Piwnica-Worms D, Pike LJ. Luciferase fragment complementation imaging of conformational changes in the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:7474–7482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808041200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]