Abstract

X-ray diffraction and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy (NMR) are the staple methods for revealing atomic structures of proteins. Since crystals of biomolecular assemblies and membrane proteins often diffract weakly and such large systems encroach upon the molecular tumbling limit of solution NMR, new methods are essential to extend structures of such systems to high resolution. Here we present a method that incorporates solid-state NMR restraints alongside of X-ray reflections into the conventional model building and refinement steps of structure calculations. Using the 3.7 Å crystal structure of the integral membrane protein complex DsbB-DsbA as a test case yielded a significantly improved backbone precision of 0.92 Å in the transmembrane region, a 58% enhancement from using X-ray reflections alone. Furthermore, addition of solid-state NMR restraints greatly improved the overall quality of the structure by promoting 22% of DsbB transmembrane residues into the most favored regions of Ramachandran space in comparison to the crystal structure. This method is widely applicable to any protein system where X-ray data are available, and is particularly useful for the study of weakly diffracting crystals.

Keywords: membrane protein, solid-state NMR, X-ray reflections, high resolution, joint calculation

Membrane proteins play a crucial role in most biological processes, such as immune recognition, signal and energy transduction and ion conduction. Thus, the study of membrane protein structure-function relationships and mechanistic features promises new frontiers in our understanding of these fundamental processes and in the medicinal therapies designed to mediate or thwart their pathologies (White 2009). However, only about 10% of the estimated 1,700 membrane protein structure families have been elucidated. A striking number of these structures exhibit relatively low-resolution (~3–4 Å) due to the challenges of solubilizing and crystallizing hydrophobic membrane proteins. Occasionally, hydrophilic and soluble partners or antibodies have facilitated the crystallization of membrane proteins (Inaba et al. 2009; Inaba et al. 2006; Li et al. 2010; Malojčić et al. 2008). Solution NMR has had several key successes in solving membrane protein structures (Bayrhuber et al. 2008; Gautier et al. 2010; Hiller et al. 2008; Van Horn et al. 2009; Zhou et al. 2008), but the challenge of long global rotational correlation times (>50 ns) of detergent-solubilized membrane proteins still exists. Solid-state NMR (SSNMR) has proven to be a powerful technique that is uniquely suited to studying the mechanisms of membrane proteins in a lipid-bilayer-mimicking environment (Cady et al. 2010; Hu et al. 2010; Mahalakshmi et al. 2008; Sharma et al. 2010; Verardi et al. 2011). Many magic-angle-spinning (MAS) SSNMR techniques have been developed to elucidate both structure and dynamics of membrane proteins (McDermott 2009). SSNMR does not rely upon crystallized samples; membrane protein samples, prepared by removing excess detergent, retain native lipids and hydrophobic cofactors (Tang et al. 2011), enabling high-resolution despite a lack of long range order. For soluble proteins, joint calculations of X-ray and solution NMR data have already produced structures of commensurate quality to those structures produced from either method alone (Chen et al. 2000; Koharudin et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2009; Matei et al. 2008; Schwieters et al. 2007; Shaanan et al. 1992). Recently, small angle X-ray scattering data combined with solution or solid-state NMR restraints have been used to refine multi-domain proteins (Gabel et al. 2008; Grishaev et al. 2008a; Grishaev et al. 2005; Grishaev et al. 2008b; Jehle et al. 2010; Nieuwkoop et al. 2010; Schwieters et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2009), and new methods combining solution and solid-state NMR for protein structure determination have been developed (Shi et al. 2009; Traaseth et al. 2009; Verardi et al. 2011). Nevertheless, the overall structural quality is limited by the resolution of the X-ray diffraction data, which is often suboptimal for membrane proteins. Therefore, combining the data obtained from low- and medium-resolution crystals with SSNMR derived high-resolution restraints should vastly improve the quality of membrane protein and membrane protein complex structures. This cooperative method holds enormous potential to determine membrane protein structures to super resolution, a term indicating that the accuracy of the protein structure exceeds the resolution of its X-ray reflections. This method is similar in principle to the recently demonstrated re-refinement of large protein complexes using restraints drawn from homology models (Schroder et al. 2010). However, the too few high quality membrane protein structures exist to warrant the routine application of this latter method for membrane proteins.

The 41 kDa membrane protein system DsbB-DsbA is the disulfide bond generating system in E. coli, which consists of the integral membrane protein DsbB (20 kDa) and the periplasmic protein DsbA (21 kDa). DsbA is responsible for forming disulfide bonds in substrate proteins in the periplasm of E. coli, while DsbB is responsible for reoxidizing DsbA and transferring the electrons to ubiquinone to continue the enzymatic cycle (Ito et al. 2008). DsbB has four transmembrane helices consisting of mainly hydrophobic residues, which makes it very difficult to crystallize DsbB by itself. Recently, single crystals of DsbB mutants have been successfully prepared when crystallized with its enzymatic partner DsbA. The resolution of the crystal structure is 3.7 Å for DsbB(C130S)-DsbA(C33A) (Inaba et al. 2006). Comprehensive 3D and 4D SSNMR experiments have been performed for de novo chemical shift assignments of DsbB (Li et al. 2008) and DsbA (Sperling et al. 2010), and thus atomic-resolution NMR restraints can be used to improve the structure model of this complex. Here we present a method of joint structure calculation of the DsbB-DsbA complex from X-ray reflections and SSNMR restraints, in which the overall backbone precision is improved by 39% over using X-ray reflections alone (1.03 Å vs. 1.70 Å).

It has been demonstrated that accurate backbone chemical shift assignments based on high-resolution multidimensional SSNMR spectroscopy can provide accurate information on protein backbone dihedral angles (Sperling et al. 2010). Hence, we obtained empirical dihedral angle restraints from the improved version of the Torsion Angle Likeliness Obtained from Shift and Sequence Similarity (TALOS+) (Shen et al. 2009) program using SSNMR assignments of most amino acids in the DsbB transmembrane helices (Li et al. 2008) and DsbA (Sperling et al. 2010). The backbone dihedral angles, φ and ψ, were predicted by using the chemical shifts of 15N, 13C′, 13Cα and 13Cβ of DsbB and DsbA in TALOS+. Good predictions (where 10 out of 10 of the best database matches fall in a consistent region in Ramachandran space) yielded 398 φ and ψ dihedral angle restraints. The average uncertainty of the dihedral angles is ± 10.9°, indicating the well-defined backbone structures of DsbB and DsbA.

In addition, we employed the strategy of selective labeling, in which [2-13C] glycerol or [1, 3-13C] glycerol is used as the carbon source during protein expression (Castellani et al. 2002), to acquire two-dimensional (2D) 13C-13C correlation experiments (Figure S1 of Supporting Information). The labeling scheme yields [2-13C-glycerol, 15N] DsbB(C41S) (2-DsbB) with mainly 13C labels at Cα atoms and [1, 3-13C-glycerol, 15N] DsbB(C41S) (1, 3-DsbB) with 13C labels at carbonyl and methylene/methyl atoms, which greatly reduces the degeneracy of the cross-peaks and eliminates or reduces the J-couplings between directly bonded 13C labels. 811 distance restraints were extracted from the spectra (136 unambiguous and 675 ambiguous distances). We employed the probabilistic assignment algorithm for automated structure determination (PASD) (Kuszewski et al. 2004) algorithm in XPLOR-NIH to obtain the ambiguous distance restraints.

A simulated annealing protocol was then used to determine the structure of DsbB(C130S)-DsbA(C33A) using Xplor-NIH (Schwieters et al. 2003). The restraints from the experimental data included backbone dihedral angles extracted from SSNMR chemical shifts using TALOS+ for both DsbB and DsbA, distance restraints from 13C-13C correlation experiments for DsbB and X-ray reflections obtained from the RCSB Protein Databank (PDB code 2HI7 or 2ZUP. These crystal structures were determined using very similar X-ray data) (Inaba et al. 2009; Inaba et al. 2006). The commonly used potential terms of bonds, angles, improper torsions, van der Waals, hydrogen bonds, distances from 13C-13C correlation experiments and dihedral angles (TALOS+ restraints) were included along with the explicit energy term for direct refinement against crystallographic structure factors (X-ray reflections). Table 1 shows the statistical comparison, based on the 10 lowest-energy structures out of 200 calculated, of the same joint-calculation protocol performed with X-ray reflections alone and with both restraints together. Further validations of calculated structures and R factors are summarized in Table S1 of Supporting Information. The average r.m.s. deviation of backbone atoms (bbRMSD) from their mean positions was improved from 1.70 Å (X-ray reflections only) to 1.03 Å (X-ray reflections and SSNMR restraints). In the transmembrane helices of DsbB, where most NMR restraints of DsbB are located, bbRMSD improvement is approximately 58% over the X-ray data alone (0.92 Å vs. 2.20 Å). The improvement in precision is evident in Figure 1, which shows overlays of the 10 lowest energy structures calculated with and without SSNMR restraints in panels A and B, respectively (both sets of structures include X-ray restraints).

Table 1.

Statistics of the joint calculation by SSNMR and X-ray for DsbB-DsbA.

| DsbB-DsbA | ||

|---|---|---|

| Datasets | X-ray | X-ray + SSNMR |

| NMR restraints | ||

| Distance restraints | ||

| Unambiguous NOE | - | 136 |

| Ambiguous NOE | - | 675 |

| Dihedral angle restraints | ||

| φ, ψ | - | 398 |

| X-ray data | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| No. reflections | 10159 | 10159 |

| Structure statistics | ||

| Violations (mean and s.d.) | ||

| Distance restraints (Å) | - | 0.121 (0.003) |

| Dihedral angle restraints (°) | - | 0.294 (0.048) |

| Deviations from idealized geometry | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 (0.001) | 0.007 (0.001) |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.801 (0.018) | 0.867 (0.012) |

| Impropers (°) | 0.554 (0.020) | 0.632 (0.016) |

| Average r.m.s. deviationa (Å) | ||

| Overall backbone | 1.70 | 1.03 |

| All heavy | 2.38 | 1.71 |

| DsbB transmembrane backboneb | 2.20 | 0.92 |

| Ramachandran space analysisc (%) | ||

| Most favored | 72.0 | 94.0 |

| Additionally allowed | 24.0 | 2.0 |

| Generously allowed | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Disallowed | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Numbers in parentheses represent the uncertainties.

Average r.m.s. deviation was calculated among 10 lowest-energy structures out of 200.

The transmembrane helices consist of residues 17 – 30, 43 – 60, 72 – 85, 146 – 161.

Performed in PROCHECK(Laskowski et al. 1993) for the crystal structure or one jointly-calculated structure in DsbB transmembrane regions.

Figure 1.

Overlay of 10 lowest-energy structures of DsbB-DsbA, calculated against (A) only X-ray reflections and (B) X-ray reflections and SSNMR restraints. The colors represent the secondary structure elements (magenta:α-helix, cyan and white: coil and turn, yellow:β-strand). The grey band indicates the membrane. The bbRMSD of the transmembrane regions has improved 58% with the joint calculation.

Furthermore, PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1993) validation of standard protein geometry for the calculated structure showed that the addition of SSNMR restraints promoted approximately 22% of DsbB transmembrane residues into most favored regions of Ramachandran space. The Cα coordinates of the structures calculated with distance restraints and X-ray reflections (data not shown) have a RMSD of 2.12 Å to the crystal structure, while adding dihedral angle restraints to the calculation improves the reference RMSD to 1.71 Å, indicating that the jointly calculated structure is indeed more accurate. The sample conditions for different techniques can be a contributing factor to structural differences. Therefore, we compared the de novo SSNMR chemical shifts of DsbB in native lipids with solution NMR chemical shifts of DsbB in detergent micelles. Figure 2 illustrates the similarities of most residues in transmembrane helices. A few outliers like L17, L43, G61, A62, L146, V160, V161 are close to the membrane surface, which may interact differently with detergents and lipids. Subtle structural differences are observed by comparing the solution structure with X-ray and jointly-calculated structures (solution vs. X-ray: 1.65 Å and solution vs. jointly-calculated: 1.64 Å just in the transmembrane helices).

Figure 2.

Comparison of chemical shifts of DsbB in solution (C44S, C104S) (Zhou et al. 2008) and in solid state (C41S). (A) 13CO chemical shifts, RMSD = 0.56 ppm; (B) 13Cα chemical shifts, RMSD = 0.70 ppm; (C) 13Cβ chemical shifts, RMSD = 0.95 ppm; (D) 15N chemical shifts, RMSD = 1.30 ppm. Outliers are marked.

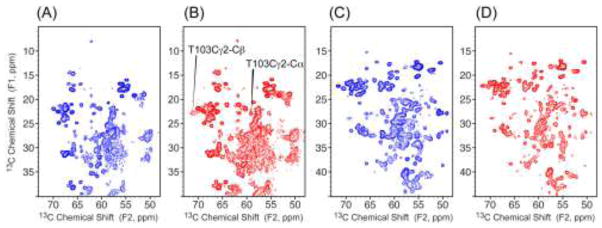

In order to be certain that NMR restraints obtained from DsbB and DsbA alone are relevant to the mutants in the complex, 2D 13C-13C correlation spectra have been acquired on [U-13C, 15N]DsbB(C41S) (U-DsbB), [U-13C, 15N]DsbB in a covalent complex with natural abundance DsbA(C33S) (U-DsbB/DsbA), [U-13C, 15N]DsbA (U-DsbA), and natural abundance DsbB in a covalent complex with [U-13C, 15N]DsbA(C33S) (DsbB/U-DsbA) to compare the chemical shifts. Figure 3 shows the expansions of 2D 13C-13C correlation spectra of these four samples, respectively. The spectra show the crosspeaks between Cα and Cβ, Cγ and Cδ sidechains for the majority of protein residues, which are the most sensitive to the secondary structure changes. The U-DsbB and U-DsbB/DsbA exhibit mostly the same crosspeaks representing the same chemical environments, except one residue T103 appearing in U-DsbB/DsbA. This residue, T103, is close to C104, which is covalently bonded to C30 in DsbA and thus experiences very different dynamics between the U-DsbB sample, where this loop is very mobile, and the U-DsbB/DsbA sample, where this loop is more spatially confined. As for DsbA, no significant differences were observed between 2D 13C-13C spectra of U-DsbA and DsbB/U-DsbA (Figure 3c, d). Therefore, using SSNMR restraints collected from DsbB and DsbA alone in the joint calculation of the DsbB-DsbA complex is valid.

Figure 3.

Comparison of 2D expansions of the13C-13C correlation spectra of (A) U-DsbB, (B) U-DsbB/DsbA, (C) U-DsbA and (D) DsbB/U-DsbA. The spectra were collected at 750 MHz (1H frequency) with a spinning speed of 12.5 kHz and 25 ms DARR mixing.

In summary, we have demonstrated a method for improving structures of membrane proteins by joint structure calculations including X-ray reflections and SSNMR restraints for the DsbB(C130S)-DsbA(C33A) membrane protein complex. This method can be generally applied to larger membrane proteins and membrane protein complexes, where X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy alone cannot provide high-resolution structures. By combining the strengths of X-ray crystallography for framing the protein fold and SSNMR for the ability to define the local structure at atomic-resolution, this protocol of joint structure determination can address the challenges in solving structures of membrane proteins to atomic resolution. SSNMR can also provide additional information on the cofactors in the active site of membrane proteins (Tang et al. 2011). Taking advantage of versatile sample conditions in membrane proteins, SSNMR can potentially be used to examine various mutants representing the different stages in the electron transfer pathway of disulfide bond formation. Moreover, Xplor-NIH allows additional restraints to be incorporated conveniently in the protocol, beyond those used in this study. For instance, 1H-1H distances from proton detection of perdeuterated proteins (Zhou et al. 2007) and conformation-sensitive chemical shift anisotropies (Harper et al. 2006; Wylie et al. 2009) could be possible restraints. Selectively labeled proteins within membrane protein complexes or their cofactors will provide site-specific distance restraints for achieving high resolution of protein-protein interfaces and binding sites. New methods under development, such as dynamic nuclear polarization (Maly et al. 2008) and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (Wickramasinghe et al. 2009), have great potential to significantly improve the sensitivity of membrane protein samples for SSNMR data collection (10~20 times compared to current experimental conditions). We expect a rapid acceleration in SSNMR data collection in the near future. These technologies will further facilitate this joint structure elucidation method for large membrane proteins and protein complexes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM075937, S10RR025037, and R01GM073770 ARRA supplement to C.M.R., and NRSA F32GM095344 to A.E.N), the Molecular Biophysics Training Grant (PHS 5 T32 GM008276) and Ullyot Fellowship to L.J.S., and the NIH Intramural Research Program of CIT to C.D.S. The authors thank the School of Chemical Sciences NMR Facility at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for assistance with data acquisition and Mike Hallock for helpful assistance with structure calculations.

Footnotes

Accession codes

Atomic coordinates and structural constraints have been deposited in the PDB with ID code 2LEG, and NMR data have been deposited in BioMagResBank with access code 17710.

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, 13C-13C correlation spectra of glycerol labeled DsbB samples and validations of structural calculations of DsbB-DsbA.

References

- Bayrhuber M, Meins T, Habeck M, Becker S, Giller K, Villinger S, Vonrhein C, Griesinger C, Zweckstetter M, Zeth K. Structure of the human voltage-dependent anion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15370–15375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808115105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady SD, Schmidt-Rohr K, Wang J, Soto CS, DeGrado WF, Hong M. Structure of the amantadine binding site of influenza M2 proton channels in lipid bilayers. Nature. 2010;463:689–692. doi: 10.1038/nature08722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani F, van Rossum B, Diehl A, Schubert M, Rehbein K, Oschkinat H. Structure of a protein determined by solid-state magic-angle- spinning NMR spectroscopy. Nature. 2002;420:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nature01070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Clore GM. A systematic case study on using NMR models for molecular replacement: p53 tetramerization domain revisited. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:1535–1540. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900012002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel F, Simon B, Nilges M, Petoukhov M, Svergun D, Sattler M. A structure refinement protocol combining NMR residual dipolar couplings and small angle scattering restraints. J Biomol NMR. 2008;41:199–208. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9258-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier A, Mott HR, Bostock MJ, Kirkpatrick JP, Nietlispach D. Structure determination of the seven-helix transmembrane receptor sensory rhodopsin II by solution NMR spectroscopy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:768–774. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishaev A, Tugarinov V, Kay LE, Trewhella J, Bax A. Refined solution structure of the 82-kDa enzyme malate synthase G from joint NMR and synchrotron SAXS restraints. J Biomol NMR. 2008a;40:95–106. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishaev A, Wu J, Trewhella J, Bax A. Refinement of multidomain protein structures by combination of solution small-angle X-ray scattering and NMR data. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16621–16628. doi: 10.1021/ja054342m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishaev A, Ying J, Canny MD, Pardi A, Bax A. Solution structure of tRNAVal from refinement of homology model against residual dipolar coupling and SAXS data. J Biomol NMR. 2008b;42:99–109. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9267-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JK, Grant DM, Zhang Y, Lee PL, Von Dreele R. Characterizing challenging microcrystalline solids with solid-state NMR shift tensor and synchrotron X-ray powder diffraction data: structural analysis of ambuic acid. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1547–1552. doi: 10.1021/ja055570j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller S, Garces RG, Malia TJ, Orekhov VY, Colombini M, Wagner G. Solution structure of the integral human membrane protein VDAC-1 in detergent micelles. Science. 2008;321:1206–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.1161302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F, Luo W, Hong M. Mechanisms of proton conduction and gating in influenza M2 proton channels from solid-state NMR. Science. 2010;330:505–508. doi: 10.1126/science.1191714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba K, Murakami S, Nakagawa A, Iida H, Kinjo M, Ito K, Suzuki M. Dynamic nature of disulphide bond formation catalysts revealed by crystal structures of DsbB. EMBO J. 2009;28:779–791. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba K, Murakami S, Suzuki M, Nakagawa A, Yamashita E, Okada K, Ito K. Crystal structure of the DsbB-DsbA complex reveals a mechanism of disulfide bond generation. Cell. 2006;127:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Inaba K. The disulfide bond formation (Dsb) system. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehle S, Rajagopal P, Bardiaux B, Markovic S, Kuhne R, Stout JR, Higman VA, Klevit RE, van Rossum BJ, Oschkinat H. Solid-state NMR and SAXS studies provide a structural basis for the activation of alphaB-crystallin oligomers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1037–1042. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koharudin LM, Furey W, Liu H, Liu YJ, Gronenborn AM. The phox domain of sorting nexin 5 lacks phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PtdIns(3)P) specificity and preferentially binds to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2) J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23697–23707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuszewski J, Schwieters CD, Garrett DS, Byrd RA, Tjandra N, Clore GM. Completely automated, highly error-tolerant macromolecular structure determination from multidimensional nuclear overhauser enhancement spectra and chemical shift assignments. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6258–6273. doi: 10.1021/ja049786h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, Macarthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. Procheck - a Program to Check the Stereochemical Quality of Protein Structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Schulman S, Dutton RJ, Boyd D, Beckwith J, Rapoport TA. Structure of a bacterial homologue of vitamin K epoxide reductase. Nature. 2010;463:507–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Berthold DA, Gennis RB, Rienstra CM. Chemical shift assignment of the transmembrane helices of DsbB, a 20-kDa integral membrane enzyme, by 3D magic-angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. Protein Sci. 2008;17:199–204. doi: 10.1110/ps.073225008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Koharudin LM, Gronenborn AM, Bahar I. A comparative analysis of the equilibrium dynamics of a designed protein inferred from NMR, X-ray, and computations. Proteins. 2009;77:927–939. doi: 10.1002/prot.22518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalakshmi R, Marassi FM. Orientation of the Escherichia coli outer membrane protein OmpX in phospholipid bilayer membranes determined by solid-State NMR. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6531–6538. doi: 10.1021/bi800362b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malojčić G, Owen RL, Grimshaw JPA, Glockshuber R. Preparation and structure of the charge-transfer intermediate of the transmembrane redox catalyst DsbB. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3301–3307. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly T, Debelouchina GT, Bajaj VS, Hu KN, Joo CG, Mak-Jurkauskas ML, Sirigiri JR, van der Wel PCA, Herzfeld J, Temkin RJ, Griffin RG. Dynamic nuclear polarization at high magnetic fields. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:052211. doi: 10.1063/1.2833582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matei E, Furey W, Gronenborn AM. Solution and crystal structures of a sugar binding site mutant of cyanovirin-N: no evidence of domain swapping. Structure. 2008;16:1183–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott A. Structure and Dynamics of Membrane Proteins by Magic Angle Spinning Solid-State NMR. Annu Rev Biophys. 2009;38:385–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop AJ, Rienstra CM. Supramolecular protein structure determination by site-specific long-range intermolecular solid state NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:7570–7571. doi: 10.1021/ja100992y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder GF, Levitt M, Brunger AT. Super-resolution biomolecular crystallography with low-resolution data. Nature. 2010;464:1218–1222. doi: 10.1038/nature08892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwieters CD, Clore GM. A physical picture of atomic motions within the Dickerson DNA dodecamer in solution derived from joint ensemble refinement against NMR and large-angle X-ray scattering data. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1152–1166. doi: 10.1021/bi061943x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N, Clore GM. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J Magn Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwieters CD, Suh JY, Grishaev A, Ghirlando R, Takayama Y, Clore GM. Solution Structure of the 128 kDa Enzyme I Dimer from Escherichia coli and Its 146 kDa Complex with HPr Using Residual Dipolar Couplings and Small- and Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13026–13045. doi: 10.1021/ja105485b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaanan B, Gronenborn AM, Cohen GH, Gilliland GL, Veerapandian B, Davies DR, Clore GM. Combining Experimental Information from Crystal and Solution Studies - Joint X-Ray and NMR Refinement. Science. 1992;257:961–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1502561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Yi M, Dong H, Qin H, Peterson E, Busath DD, Zhou HX, Cross TA. Insight into the mechanism of the influenza A proton channel from a structure in a lipid bilayer. Science. 2010;330:509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.1191750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Delaglio F, Cornilescu G, Bax A. TALOS plus: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J Biomol NMR. 2009;44:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Traaseth NJ, Verardi R, Cembran A, Gao J, Veglia G. A refinement protocol to determine structure, topology, and depth of insertion of membrane proteins using hybrid solution and solid-state NMR restraints. J Biomol NMR. 2009;44:195–205. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9328-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling LJ, Berthold DA, Sasser TL, Jeisy-Scott V, Rienstra CM. Assignment strategies for large proteins by magic-angle spinning NMR: the 21-kDa disulfide bond forming enzyme DsbA. J Mol Biol. 2010;399:268–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M, Sperling LJ, Berthold DA, Nesbitt AE, Gennis RB, Rienstra CM. Solid-state NMR study of the charge-transfer complex between ubiquinone-8 and disulfide bond generating membrane protein DsbB. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4359–4366. doi: 10.1021/ja107775w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traaseth NJ, Shi L, Verardi R, Mullen DG, Barany G, Veglia G. Structure and topology of monomeric phospholamban in lipid membranes determined by a hybrid solution and solid-state NMR approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:10165–10170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904290106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn WD, Kim HJ, Ellis CD, Hadziselimovic A, Sulistijo ES, Karra MD, Tian CL, Sonnichsen FD, Sanders CR. Solution Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Structure of Membrane-Integral Diacylglycerol Kinase. Science. 2009;324:1726–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.1171716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verardi R, Shi L, Traaseth NJ, Walsh N, Veglia G. Structural topology of phospholamban pentamer in lipid bilayers by a hybrid solution and solid-state NMR method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9101–9106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016535108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zuo X, Yu P, Byeon IJ, Jung J, Wang X, Dyba M, Seifert S, Schwieters CD, Qin J, Gronenborn AM, Wang YX. Determination of multicomponent protein structures in solution using global orientation and shape restraints. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:10507–10515. doi: 10.1021/ja902528f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SH. Biophysical dissection of membrane proteins. Nature. 2009;459:344–346. doi: 10.1038/nature08142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasinghe NP, Parthasarathy S, Jones CR, Bhardwaj C, Long F, Kotecha M, Mehboob S, Fung LWM, Past J, Samoson A, Ishii Y. Nanomole-scale protein solid-state NMR by breaking intrinsic 1H T1 boundaries. Nat Methods. 2009;6:215–218. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie BJ, Schwieters CD, Oldfield E, Rienstra CM. Protein Structure Refinement Using 13Cα Chemical Shift Tensors. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:985–992. doi: 10.1021/ja804041p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou DH, Shea JJ, Nieuwkoop AJ, Franks WT, Wylie BJ, Mullen C, Sandoz D, Rienstra CM. Solid-state protein-structure determination with proton-detected triple-resonance 3D magic-angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:8380–8383. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YP, Cierpicki T, Jimenez RHF, Lukasik SM, Ellena JF, Cafiso DS, Kadokura H, Beckwith J, Bushweller JH. NMR solution structure of the integral membrane enzyme DsbB: Functional insights into DsbB-catalyzed disulfide bond formation. Mol Cell. 2008;31:896–908. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.