Abstract

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) is potentially an important aid to public health decision-making but, with some notable exceptions, its use and impact at the level of individual countries is limited. A number of potential reasons may account for this, among them technical shortcomings associated with the generation of current economic evidence, political expediency, social preferences and systemic barriers to implementation. As a form of sectoral CEA, Generalized CEA sets out to overcome a number of these barriers to the appropriate use of cost-effectiveness information at the regional and country level. Its application via WHO-CHOICE provides a new economic evidence base, as well as underlying methodological developments, concerning the cost-effectiveness of a range of health interventions for leading causes of, and risk factors for, disease.

The estimated sub-regional costs and effects of different interventions provided by WHO-CHOICE can readily be tailored to the specific context of individual countries, for example by adjustment to the quantity and unit prices of intervention inputs (costs) or the coverage, efficacy and adherence rates of interventions (effectiveness). The potential usefulness of this information for health policy and planning is in assessing if current intervention strategies represent an efficient use of scarce resources, and which of the potential additional interventions that are not yet implemented, or not implemented fully, should be given priority on the grounds of cost-effectiveness.

Health policy-makers and programme managers can use results from WHO-CHOICE as a valuable input into the planning and prioritization of services at national level, as well as a starting point for additional analyses of the trade-off between the efficiency of interventions in producing health and their impact on other key outcomes such as reducing inequalities and improving the health of the poor.

Introduction

The inclusion of an economic perspective in the evaluation of health and health care has become an increasingly accepted component of health policy and planning. Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) has been used as a tool for addressing issues of efficiency in the allocation of scarce health resources, providing as it does a method for comparing the relative costs as well as health gains of different (and often competing) health interventions. Several country experiences have shown that cost-effectiveness information can be used alongside other types of information to aid different policy decisions. For example, it has been used to decide which pharmaceuticals should be reimbursed from public funds in Australia [1] and several European countries [2-4]. At an international level, sectoral CEA has been employed by the World Bank to identify disease control priorities in developing countries and essential packages of care for countries at different levels of economic development [5,6].

Beyond these examples, however, the use and application of CEA information to guide the priority-setting process of national governments remains rather limited. A number of potential reasons may account for this situation, among them political expediency, social preferences and systemic barriers to implementation. In addition, there are a number of more technical shortcomings associated with the generation of economic evidence capable of supporting sector-wide priority-setting in health, including data unavailability, methodological inconsistency across completed economic evaluations, and the limited generalizability or transferability of findings to settings beyond the location of the original study [7,8].

In this paper, we address a number of technical constraints to the appropriate use of cost-effectiveness information in health policy and planning. We then outline a process by which country-level decision-makers and programme managers can carry out their own context-specific analysis of the relative cost-effectiveness of interventions for reducing leading causes of national disease burden using CEA information from the WHO-CHOICE project (CHOosing Interventions that are Cost-Effective; http://www.who.int/evidence/cea). We conclude with a brief discussion of how sectoral CEA can contribute to broader priority-setting exercises at the national level.

Sectoral cost-effectiveness analysis

The majority of cost-effectiveness studies to date have informed technical efficiency questions. Technical efficiency refers to the optimal use of resources in the delivery or production of a given health intervention – ensuring there is no waste of resources. Most country applications focus on local and marginal improvements in technical efficiency. The term allocative efficiency, on the other hand, is typically used in health economics to refer to the distribution of resources among different programmes or interventions in order to achieve the maximum possible socially desired outcome for the available resources. By definition, addressing issues of allocative efficiency in health requires a broader, sectoral approach to evaluation, since the relative costs and effects of interventions for a wide range of diseases and risk factors need to be determined in order to identify the optimal mix of interventions that will meet the overall objectives of the health system, such as the maximization of health itself or the equitable distribution of health gains across the population.

By sectoral CEA we mean that all alternative uses of resources are evaluated in a single exercise, with an explicit resource constraint [9-12]. Prior to the WHO-CHOICE project, only a few applications of this broader use of CEA – in which a wide range of preventive, curative and rehabilitative interventions that benefit different groups within a population are compared in order to inform decisions about the optimal mix of interventions – can be found. Examples include the work of the Oregon Health Services Commission [13], the World Bank Health Sector Priorities Review [5] and the Harvard Life Saving Project [14]. Of these, only the World Bank attempted to make international or global comparisons. This is partly because there are a number of common technical and implementation problems that have been experienced by decision-makers interested in using the results of CEA to guide resource allocation decisions across the sector as a whole [8]. They include:

Methodological inconsistency

the heterogeneity of methods and outcome measures used in economic evaluations conducted by different investigators in different settings has complicated both the synthesis and the interpretation of cost-effectiveness results. For example, the measurement of costs may or may not have included assessment of informal care, travel and productivity losses so that the results of one study are not comparable with those of another, even if they were undertaken in the same setting.

Data unavailability

There remain considerable gaps in the cost-effectiveness evidence base, particularly for historically marginalized services and for currently under-served populations (e.g. mental health care in developing countries). This has limited the ability of policy-makers to address issues of allocative efficiency in the health sector.

Lack of generalizability

No country has yet been able to undertake all the studies necessary to compare the cost-effectiveness of all possible interventions in their own setting. They must borrow results from other settings. CEA findings, particularly costs, do not travel well due often to differences in health and economic systems. Because results have not been presented in ways that allow for transferability across settings, this has limited their use to the specific context in which they were derived.

Limited technical or implementation capacity

There is a shortage, particularly in lower-income countries, not only in terms of technical expertise to undertake economic evaluations in the first place, but also in terms of health service management capacity or political willingness to translate and implement findings into everyday health care practice.

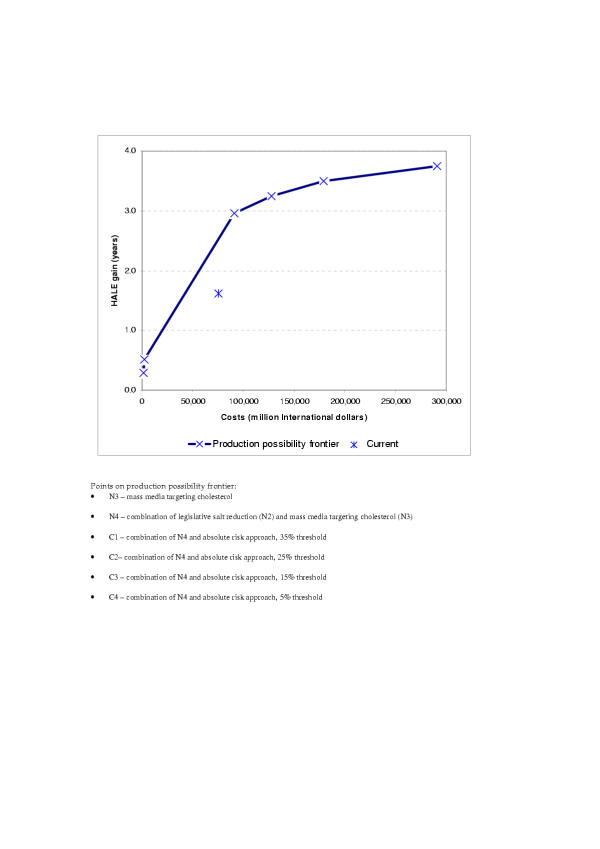

Despite the limitations, this type of sectoral analysis is potentially important, although it is also clear that it can and should be only one input into the priority-setting process. As is shown in Figure 1, the health system framework developed by WHO is concerned not just with the generation of health itself, but also with meeting other key social goals and preferences, including being responsive to consumers and ensuring that the financial burden of paying for the health system is distributed fairly across households [15]. Figure 1 also shows that the health system seeks to reduce inequalities in health and responsiveness as well as increasing aggregate levels. Yet often health interventions do not adequately reach the poor despite being cost-effective and widely promoted. A benefit-incidence analysis of 44 countries across Africa, Asia and Latin America showed, for example, that interventions like oral dehydration and immunization – technologies developed with the needs of the poor particularly in mind – do not reach the target group. Only one-half of all cases of diarrhoea among children in the poorest 20% of families had been treated with some kind of oral liquid. Similarly, immunization programmes are not reaching the poor nearly so well as they are the better off. On average, immunization coverage in a developing country's poorest 20% of the population is around 35%–40%, slightly more than half the level achieved in the richest 20% [16,17].

Figure 1.

Health System Goals.

In short, cost-effectiveness analysis can show what combination of interventions would maximize the level of population health for the available resources. Since it is only one input – albeit an important one – to the decision-making process, the information it provides needs to be evaluated against the impact of different mixes of interventions on other social goals [18]. We return to this issue later in the paper.

Generalized cost-effectiveness analysis: a new approach to sectoral CEA

Conceptual foundations

Generalized CEA has been developed to meet a number of the limitations in the implementation of sectoral CEA that were discussed earlier [10]. One of the desired characteristics for sectoral CEA is to identify current allocative inefficiencies as well as opportunities presented by new interventions. A further desired characteristic is that it be presented in a way that can be translated across settings to the maximum extent possible, so that the results can benefit as many decision-makers as possible. Generalized CEA does this in two ways.

1) The costs and health benefits of a set of related interventions are evaluated, singly and in combination, with respect to the counterfactual case that those interventions are not in place (a reference situation referred to as the null scenario).

2) CEA results are used to classify interventions into those that are very cost-effective, cost-ineffective, and somewhere in between rather than using a traditional league table approach.

The advantage of using the counterfactual or null scenario as the basis of the analysis is that it can identify current allocative inefficiencies as well as the efficiency of opportunities presented by new interventions [10]. From the starting point of the situation that would exist in the absence of the interventions being analyzed, the costs and effects on population health of adding interventions singly (and in combination) can be estimated, to give the complete set of information required to evaluate the health maximizing combination of interventions for any given level of resource constraints.

Traditional cost-effectiveness analysis does not evaluate the efficiency of the current mix of interventions, but considers only the efficiency of small changes, usually increases, in resource use at the margin (i.e. the starting point for analysis is the current situation of usual care). This shows whether a new procedure is more cost-effective than the existing one but avoids the question of whether the current procedure was worth doing, implicitly taking it as given that something would have to be done in that particular area. Because the current mix of interventions varies substantially across countries, the costs and effects of small changes in resource use also vary substantially, which is one factor limiting the transferability of results across settings. Removal of this constraint by using the counterfactual of what would happen in the absence of the interventions means that the results not only allow assessment of the efficiency of current resource use, but are also more generalizable across populations sharing similar demographic or epidemiological characteristics.

One perceived disadvantage of using a counterfactual situation as a starting point for analysis is that policy-makers are more familiar with moving from the known, current situation. However, by incorporating currently implemented strategies (at specified levels of effective coverage) in the set of interventions for analysis, the ability to assess the incremental costs and effects of changes to the current allocation of resources is in fact preserved. In any case, Generalized CEA should not be viewed as a substitute to the acquisition of more context-specific economic evidence on the efficiency of adding new health technologies to the existing intervention mix. Both types of analysis are, in fact, complementary to each other. Generalized CEA is most useful to decision-makers in terms of broadly identifying within a sectoral assessment framework an efficient mix of interventions. Thus, as a first step in policy analysis using Generalized CEA, interventions are first classified into groups that interact in terms of costs or effects. Within each group, and at different levels of coverage, interventions are evaluated singly and then in combination, allowing for non-linear interactions in terms of effectiveness (multiplicative) as well as costs ([dis]economies of scope). As a result, the most efficient combination for a given resource constraint is identified. Efficient combinations are then compared across mutually exclusive groups in a single league table, ranked according to the cost per unit of health gain achieved. Subsequently, threshold values can be decided for classifying interventions into, say, those that are very cost-effective, those that are cost-ineffective and those in between.

Incremental analysis, which is constrained by the current mix of interventions, can subsequently be employed to provide more context-specific information on how this efficient mix of interventions can best be achieved in a particular setting.

Practical implementation

The WHO-CHOICE project, using Generalized CEA, has been established to provide key information to policy-makers wishing to implement sectoral CEA. WHO-CHOICE has assembled sub-regional databases on the cost-effectiveness of an extensive range of interventions for leading causes of disease burden, including analysis of the interactions inherent in many combined interventions http://www.who.int/evidence/cea. A recent analysis of the cost-effectiveness of interventions for reducing exposure to leading risk factors for disease appears in the World Health Report 2002 [19]. The generation of such databases, which removes an important impediment to the analysis of health sector-wide allocative efficiency, has been facilitated by a number of methodological strategies:

• Use of a common set of analytical tools in WHO-CHOICE has overcome the problem of synthesizing studies that employ different perspectives and measures [20]. In order to collect, synthesize, analyze and report the costs and effects in a standardized manner, several tools have been developed. A multi-state modelling tool, PopMod [21] allows the analyst to estimate health effects by tracing what would happen to each age and sex cohort of a given population over 100 years, with and without each intervention. In order to collect programme-level costs associated with running the intervention (such as administration, training, and media) and patient-level costs (such as primary-care visits, diagnostics tests and medicines), a standard costing tool, Cost-It [22], has been developed. Finally, a tool has been developed for analysing the uncertainty around point estimates of cost-effectiveness (MCLeague [23]).

• Estimation of a null scenario as the starting point for analysis of the costs and effects of current and new interventions enhances the comparability of results, although it should be emphasized that local analysts may need to modify certain parameters (e.g. demographic structures, epidemiological characteristics, treatment coverage) in order to more accurately reflect a country's specific circumstances.

• WHO-CHOICE results to date have been made available at the level of 14 epidemiological sub-regions of the world (see Table 1). This is a compromise between providing detailed information on all interventions in all 192 member countries of WHO, something that is not possible in the shorter term, and the global approach that has been used in the past [5]. Generation of a single global estimate of the costs and effectiveness of a given intervention has not been attempted since such estimates provide almost no information that decision-makers can use in a country context.

Table 1.

Epidemiological sub-regions for reporting results of WHO-CHOICE

| Region* | Mortality stratum** | Countries |

| AFR | D | Algeria, Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Chad, Comoros, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Niger, Nigeria, Sao Tome And Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Togo |

| AFR | E | Botswana, Burundi, Central African Republic, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic Of The Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Swaziland, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe |

| AMR | A | Canada, United States Of America, Cuba |

| AMR | B | Antigua And Barbuda, Argentina, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Grenada, Guyana, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Saint Kitts And Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent And The Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad And Tobago, Uruguay, Venezuela |

| AMR | D | Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Haiti, Nicaragua, Peru |

| EMR | B | Bahrain, Cyprus, Iran (Islamic Republic Of), Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates |

| EMR | D | Afghanistan, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Morocco, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen |

| EUR | A | Andorra, Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, San Marino, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom |

| EUR | B | Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Tajikistan, The Former Yugoslav Republic Of Macedonia, Serbia and Montenego, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan |

| EUR | C | Republic of Moldova, Russian Federation, Ukraine |

| SEAR | B | Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand |

| SEAR | D | Bangladesh, Bhutan, Democratic People's Republic Of Korea, India, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal |

| WPR | A | Australia, Japan, Brunei Darussalam, New Zealand, Singapore |

| WPR | B | Cambodia, China, Lao People's Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Mongolia, Philippines, Republic Of Korea, Viet Nam |

| Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Micronesia (Federated States Of), Nauru, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu |

* Regions: AFR = Africa Region; AMR = Region of the Americas; EMR = Eastern Mediterranean Region; EUR = European Region; SEAR = South East Asian Region; WPR = Western Pacific Region ** Subregions: A = have very low rates of adult and child mortality; B = low adult, low child; C = high adult, low child; D = high adult, high child; E = very high adult, high child mortality.

• The use of an uncertainty framework, in which cost-effectiveness estimates for multiple interventions are presented in terms of their probability of being cost-effective at different budget levels, provides decision-makers with policy-relevant data on the choices to be made under conditions of resource expansion (or reduction) [23,24].

• Finally, a number of assumptions have been made with regard to the efficiency of implemented interventions. For example, in most settings it is assumed that health care facilities deliver services at 80% capacity utilization (e.g. that health personnel are fully occupied 80% of their time); or that regions have access to the lowest priced generic drugs internationally available. The reason for this is that there is limited value in providing information to decision-makers on the costs and effectiveness of interventions that are undertaken poorly (such assumptions, however, can be changed to reflect local experiences as required).

In order to facilitate more meaningful comparisons across regions, costs are expressed in international dollars (an international dollar has the same purchasing power as one US dollar has in the USA); effectiveness is measured in terms of disability-adjusted life years or DALYs averted (relative to the situation of no intervention for the disease or risk factor in question); and cost-effectiveness is described in terms of cost per DALY averted. One benefit of using the DALY as a primary measure of outcome is that it enables analysts to express population-level gain as a proportion of current disease burden (also measured in DALYs). In terms of thresholds for considering an intervention to be cost-effective, WHO-CHOICE has been using criteria suggested by the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health [25]: interventions that avert one DALY for less than average per capita income for a given country or region are considered very cost-effective; interventions that cost less than three times average per capita income per DALY averted are still considered cost-effective; and those that exceed this level are considered not cost-effective.

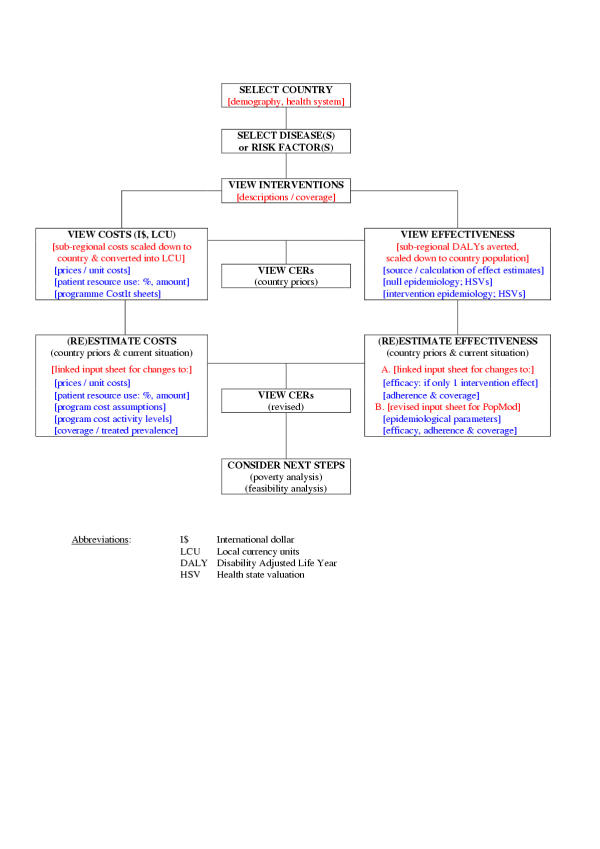

Figure 2 illustrates a way of presenting the full sectoral analysis using CHOICE results. The figure depicts the cost-effectiveness of multiple interventions in an epidemiological sub-region of Africa, called AfrD (see Table 1 for the countries in this sub-region). The figure includes a wide range of interventions, such as the provision of improved water and sanitation and preventive interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk factors. Intervention effectiveness in terms of DALYs averted is measured on the horizontal axis and annualized discounted costs of the interventions in international dollars are measured on the vertical axis. To enable the wide range of costs and effectiveness estimates for the individual interventions to be presented together, Figure 2 is drawn with the axes on a logarithmic scale. The lines drawn obliquely across the figure represent lines of equal cost-effectiveness. All points on the line at the south-east extreme have a cost-effectiveness ratio (CER) of I$1 per DALY averted. Because of the logarithmic scale, each subsequent line moving in a north-easterly direction represents a one order of magnitude increase in the CER, so all points on the next line have a CER of I$10, and the subsequent line represents a CER of I$100. The figure illustrates the variation in CERs across interventions within sub-region AfrD. Some interventions (for example, some preventive interventions aimed at reducing the incidence of HIV) avert one DALY at a cost of less than I$10. On the other hand, some preventive interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk factors cost almost I$100,000 per DALY averted. The figure allows the decision-makers to identify particularly bad buys (the brown shaded oval in Figure 2) and particularly good buys (the orange shaded oval in Figure 2) when choosing the mix of interventions they wish to ensure are provided in their setting.

Figure 2.

Cost-effectiveness of selected interventions for epidemiological sub-region AfrD (total population: 294 million).

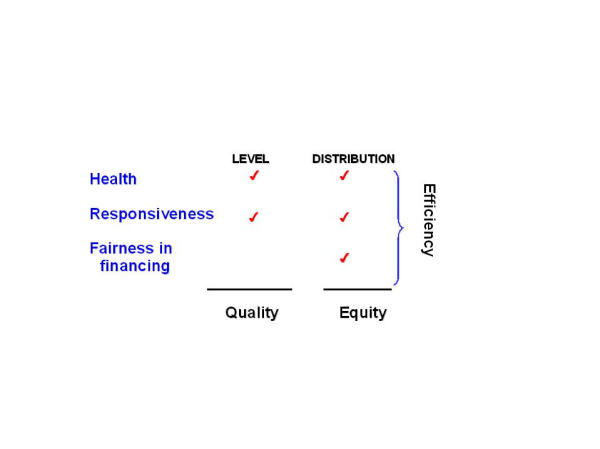

Another potential use of the results from the WHO-CHOICE exercise is to assess the performance of health systems. In WHO's health systems performance framework, health system efficiency is assessed in terms of whether the system's resources achieve the maximum possible benefit in terms of outcomes that people value [15,26]. Efficiency is the ratio of attainment (above the minimum possible in the absence of the resources) to the maximum possible attainment (also above the minimum). It reflects what proportion of the potential health system contribution to goal attainment is actually achieved for the observed level of resources. It could, in theory, be estimated for any of the health system goals or for all of them combined, but traditionally it has been limited to the assessment of the efficiency of translating expenditure into health outcomes using cost-effectiveness analysis. Figure 3 depicts the production frontier for a set of interventions to reduce the risks of cardiovascular disease in the countries of the Americas with very low rates of child and adult mortality, here called AmrA [27]. The vertical axis depicts the gain in the healthy life expectancy (HALE) of the population resulting from any given use of resources, while resource use or costs are shown on the horizontal axis. Available data on current coverage of the interventions and their costs and effectiveness allow current health attainment and costs to be estimated, represented as point *. The higher line shows the frontier estimated from information about the costs and effects of the most efficient mix of interventions at any given level or resource availability. Point * is below the frontier, suggesting that the health system is not achieving its full potential in terms of reducing the risks associated with high blood pressure and cholesterol [28]. The analysis could be used to evaluate how current resources used in preventing cardiovascular disease could be reallocated to achieve greater health benefits, as well as how any additional resources could be used most efficiently.

Figure 3.

Maximum possible health gains from selected interventions to reduce the risks of cardiovascular disease, sub-region AmrA.

The application of Generalized CEA to national-level health policy and planning

Factors to be considered in the contextualization of sub-regional cost-effectiveness data

In overcoming technical problems concerned with methodological consistency and generalizability, Generalized CEA has now generated data on avertable burden at a sub-regional level for a wide range of diseases and risk factors [19]. However, the existence of these CE data is no guarantee that findings and recommendations will actually change health policy or practice in countries. There remains a legitimate concern that global or regional CE results may have limited relevance for local settings and policy processes [29]. Indeed, it has been argued that a tension exists between Generalized CEA that is general enough to be interpretable across settings, and CEA that takes into account local context [30], and that local decision-makers need to contextualize sectoral CEA results to their own cultural, economic, political, environmental, behavioural, and infrastructural context [31].

In order to stimulate change where it may be necessary, there is a need to contextualize existing regional estimates of cost, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness to the setting in which the information will be used, since many factors may alter the actual cost-effectiveness of a given intervention across settings. These include: the availability, mix and quality of inputs, especially trained personnel, drugs, equipment and consumables; local prices, especially labour costs; implementation capacity; underlying organization structures and incentives; and the supporting institutional framework [32]. In addition, it may be necessary to address other concerns to ensure that the costs estimated on an ex-ante basis represent the true costs of undertaking an intervention in reality. For example, Lee and others [33-37]. (argue that cost estimates might not provide an accurate reflection of the true costs of implementing a health intervention in practice for a number of reasons: economic analyses can often be out of date by the time they are published [38]; the cost of pharmaceutical interventions may vary substantially depending on the type of contracts between payers, pharmacy benefits, management companies and manufacturers; or costs of care may be lowered by effective management (e.g. through negotiation, insurance companies may reduce prices). Likewise on the effectiveness side, there is a need for contextualisation. For example, effectiveness estimates used in CEA are often based on efficacy data taken from experimental and context-specific trials. When interventions are implemented in practice, effectiveness may well prove to be lower. According to Tugwell's iterative loop framework [39], the health care process is divided into different phases that are decisive in determining how effective an intervention will be in practice, including whether a patient has contact with the health care system or not, how the patient adheres to treatment recommendations, and with what quality the provider executes the intervention.

From regional to country-specific estimates

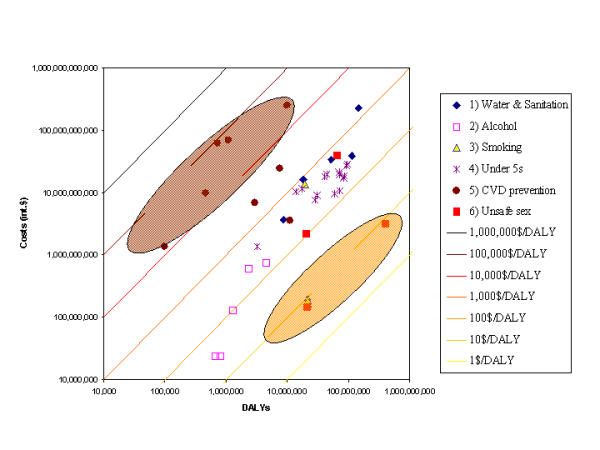

Figure 4 provides a schematic overview of the step-by-step approach by which WHO-CHOICE estimates derived at the regional level can be translated down to the context of individual countries. The following key steps are required:

Figure 4.

Steps towards the contextualisation of Generalized CEA in countries.

Choosing interventions

The first step for contextualizing WHO-CHOICE cost-effectiveness figures involves the specification and definition of interventions to be included in the analysis, including a clear description of the target population, population-level coverage and, where applicable, the treatment regimen. Since an intervention and its associated costs and benefits can be characterised not only by its technological content (e.g. a psychoactive drug) but also by the setting in which it is delivered (e.g. hospital versus community based care), service organisation issues also enter here. Interventions for some diseases may not be appropriate to a specific national setting (e.g. malaria control strategies) and can be omitted from the analysis, while interventions not already covered by the regional analyses may need to be added. Groups of interventions that are interrelated are evaluated together, since the health impact of undertaking two interventions together is not necessarily additive, nor are the costs of their joint production. Only by assessing their costs and health effects independently and in combination is it possible to account for interactions or non-linearities in costs and effects. For example, the total costs and health effects of the introduction of bed-nets in malaria control is likely to be dependent on whether the population is receiving malaria prophylaxis: this means that three interventions would be evaluated – bed-nets only, malaria prophylaxis only and bed-nets in combination with malaria prophylaxis.

Contextualization of intervention effectiveness

The population-level impact of different interventions is measured in terms of DALYs averted per year, relative to the situation of no intervention for the disease(s) or risk factor(s) in question. Key input parameters underlying this summary measure of population health under the scenario of no intervention include the population's demographic structure, epidemiological rates (incidence, prevalence, remission and case fatality) and health state valuations (HSV; the valuation of time spent in a particular health state, such as being blind or having diabetes, relative to full health [40]). If required and assuming the availability of adequate data, revised estimates of the underlying epidemiology of a disease or risk factor would necessitate some re-estimation by national-level analysts (either via regression-based prediction or by performing additional runs of the population model itself). The specific impact of an intervention is gauged by a change to one or more of these epidemiological rates or by a change to the HSV, and is a function of the efficacy of an intervention, subsequently adjusted by its coverage in the population and, where applicable, rates of adherence by its recipients. Since much of the evidence for intervention efficacy comes from randomised controlled trials carried out under favourable research or practice settings, it is important to adjust resulting estimates of efficacy according to what could be expected to occur in everyday clinical practice. Three key factors for converting efficacy into effectiveness concern treatment coverage in the target population (i.e. what proportion of the total population in need are actually exposed to the intervention), and for those receiving the intervention, both the rate of response to the treatment regimen and the adherence to the treatment. Data on these parameters can be sought and obtained at the local level, based on reviews of evidence and population surveys (if available) or expert opinion. A further potential mediator for the effectiveness of an intervention implemented in everyday clinical practice concerns the quality of care; if sufficiently good measures of service quality are available at a local level, data should also be collected for this parameter.

Contextualization of intervention costs

Intervention costs at the level of epidemiological sub-regions of the world have been expressed in international dollars (I$). This captures differences in purchasing power between different countries and allows for a degree of comparison across sub-regions that would be inappropriate using official exchange rates. For country-level analysis, costs would also be expressed in local currency units, which can be approximated by dividing existing cost estimates by the appropriate purchasing power parity exchange rate. A more accurate and preferable method is to substitute new unit prices for all the specific resource inputs in the Cost-It template (e.g. the price of a drug or the unit cost of an outpatient attendance). In addition, the quantities of resources consumed can easily be modified in line with country experiences (reflecting, for example, differences in capacity utilization). Depending on the availability of such data at a national level, it may be necessary to use expert opinion for this task.

Contextualization for different country-specific scenarios

The WHO-CHOICE database can be contextualized to the country level in three ways. The first is to evaluate all interventions on the assumption that they are done in a technically efficient manner, following the example of WHO-CHOICE. This requires minimum adjustments, limited to adjusting population numbers and structures, effectiveness levels and unit costs and quantities. This provides country policy-makers with the ideal mix of interventions – the mix that would maximize population health if they were undertaken efficiently. The second allows the analyst to capture some local constraints – for instance, scarcity of health personnel. In this case, the analysis would need to ensure that the personnel requirements imposed by the selected mix of interventions do not exceed the available supply. The third option is to modify the analysis assuming that interventions are undertaken at current levels of capacity utilization in the country and that there are local constraints on the availability of infrastructure. In this case, instead of using off-patented international prices of generic drugs, for example, the analyst may be constrained to include the prices of locally produced pharmaceutical products, or to use capacity utilization rates lower than the 80% assumed at sub-regional level.

Shifting from an existing set to a different portfolio of interventions will incur a category of costs which differ from production costs, i.e. transaction costs. Ignoring possible deviations in existing capacity and infrastructure to absorb such changes may mean that there is a significant difference between the 'theoretical' CE ratio based on Generalized CEA and one achievable in any particular setting [30]. However, the budget implications of a portfolio shift will depend on how dramatic the change will be when moving from the current mix of interventions to the optimal mix indicated by Generalized CEA. For instance, the incremental change of moving from an existing fixed facility health service in remote areas to an alternative of an emergency ambulance service might have dramatic political and budgetary implications. In contrast, a procedural change in a surgical therapy is likely to have less important budgetary consequences.

The output of such a contextualisation exercise is a revised, population-specific set of average and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for interventions addressing leading contributors to national disease burden. The potential usefulness of this information for health policy and planning can be seen in terms of confirming if current intervention strategies can be justified on cost-effectiveness grounds, and showing what other options would be cost-effective if additional resources became available. Its actual usefulness will be determined both by the availability of (or willingness to collect) local data as revised input values into the costing and effectiveness models, and by the extent to which efficiency considerations are successfully integrated with other priority-setting criteria.

The contribution of Generalized CEA to national-level priority-setting

Determination of the most cost-effective interventions for a set of diseases or risk factors, while highly informative in its own right, is not the end of the analytical process. Rather, it represents a key input into the broader task of priority-setting. For this task, the purpose is to go beyond efficiency concerns only and establish combinations of cost-effective interventions that best address stated goals of the health system, including improved responsiveness and reduced inequalities. Indeed, Generalised CEA has been specifically developed as a means by which decision makers may assess and potentially improve the overall performance (or efficiency) of their health systems, defined as how well the socially-desired mix of the five components of the three intrinsic goals is achieved compared to the available resources (Figure 1). Other allocative criteria against which cost-effectiveness arguments need to be considered include the relative severity and the extent of spillover effects among different diseases, the potential for reducing catastrophic household spending on health, and protection of human rights [12,13,18,30,31,41]. Thus, priority-setting necessarily implies a degree of trading-off between different health system goals, such that the most equitable allocation of resources is highly unlikely to be the most efficient allocation. Ultimately, the end allocation of resources arising from a priority-setting exercise, using a combination of qualitative or quantitative methods, will accord to the particular sociocultural setting in which it is carried out and to the expressed preferences of its populace and/or its representatives in government. A sequential analysis of these competing criteria, however, indicates that for the allocation of public funds, priority should be given to cost-effective interventions that are public goods (have no market) and impose high spillover effects or catastrophic costs (particularly in relation to the poor) [41], which underscores the need for prior cost-effectiveness information as a key requirement for moving away from subjective health planning (based on historical trends or political preferences) towards a more explicit and rational basis for decision-making.

There are also a number of functions of a health system that shape and support the realisation of the above stated goals, including resource generation and financing mechanisms, the organisation of services as well as overall regulation or stewardship [15]. These functions inevitably influence the priority-setting process in health and hence contribute to variations in health system performance. Indeed, it has been argued that health strategies based on efficiency criteria alone may lead to sub-optimal solutions, owing to market failures in health such as asymmetry of information between providers and patients, as well as a number of adverse incentives inherent within health systems [42]. Accordingly, the results of an efficiency analysis such as a sectoral CEA are likely to be further tempered by a number of capacity constraints and organisational issues. As already noted above, the actual availability of human and physical resources can be expected to place important limits on the extent to which (cost-effective) scaling-up of an intervention's coverage in the population can be achieved. In addition, broader organisational reforms aimed at improving health system efficiency by separating the purchasing and provision functions can be expected to lead to some impact on the final price of health care inputs or the total quantity (and quality) of service outcomes. Finally, decisions relating to the appropriate mechanism for financing health, including the respective roles of the public and private sector, can be expected to have a significant influence on the end allocation of resources. For example, should the role of the public sector be to provide an essential package of cost-effective services, leaving the private sector to provide less cost-effective services [6], or should it be to provide health insurance where private insurance markets fail (such as unpredictable, chronic and highly costly diseases, for which only potentially less cost-effective interventions are available)? [42]. Even if both objectives are pursued – providing basic services to particularly vulnerable populations while catering to the majority's inability to pay for highly costly interventions [43] – a shift away from the most efficient allocation is still implied.

Conclusion

The cost-effectiveness information currently available in the literature is almost entirely derived from the high-income countries of North America, Western Europe and Australasia [44,45]. For some disease areas (in particular for non-communicable diseases) information is lacking from Latin America, Africa and Asia, where the majority of the world's poor live (e.g. [46]). There are a number of ways in which this deficiency could be addressed. First, the results of cost-effectiveness studies in developed countries could simply be extrapolated to developing countries. This would be easy and quick but would give misleading answers and could encourage inefficient decisions to be made. Secondly, cost-effectiveness studies could be replicated in every country in which decisions need to be made for a certain disease area. This would be the safest way to proceed. However, it would be slow and costly. It would also divert limited research resources away from other important policy considerations including more appropriate mechanisms for health services delivery. This approach has not yet been fully implemented even in the richest countries. The third option – and the one proposed here – is to employ population and disease modelling techniques. These models can be adapted to the context of individual countries by applying national data and thereby provide policy-makers with relevant guidance for sector-wide priority setting. WHO-CHOICE is the first systematic attempt to provide this relevant information to countries in a way that enables analysts and programme managers to adapt results to their own settings.

It is important to emphasize that results of this type of contextualized sectoral CEA should not be used formulaically. To begin with, estimates of cost-effectiveness are imbued with an appreciable degree of uncertainty, meaning that any resource allocation procedure based purely on point estimates of CE ratios would overlook the fact that the uncertainty intervals around many competing interventions overlap, so it is simply not possible to be sure that one is more efficient than the other. Accordingly, WHO-CHOICE advocates the broad categorization of results (based on point estimates and their uncertainty intervals) into interventions that are highly cost-effective, those that are cost-ineffective and those that are somewhere in between. Furthermore, and as highlighted earlier, efficiency is only one criterion out of many that influence public health decision-making. Hence, there is always a need to balance efficiency concerns with other criteria, including the impact of interventions on poverty, equity, implementation capacity and feasibility.

Authors' contributions

RH and DC drafted the manuscript. All three authors contributed to the revision and finalisation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

WHO-CHOICE (CHOosing Interventions that are Cost-Effective) forms part of the WHO's Global Programme on Evidence for Health Policy. The following colleagues have actively contributed to the conceptual and methodological development of WHO-CHOICE and are warmly acknowledged: Dr Taghreed Adam, Dr Rob Baltussen, Dr David Evans, Raymond Hutubessy, Ben Johns, Jeremy Lauer, Dr Christopher Murray and Dr Tessa Tan Torres. The comments of reviewers Dr Viroj Tangcharoensathien and Aparnaa Somanathan are also gratefully acknowledged.

Contributor Information

Raymond Hutubessy, Email: hutubessyr@who.int.

Dan Chisholm, Email: chisholmd@who.int.

Tessa Tan-Torres Edejer, Email: tantorrest@who.int.

References

- Hailey D. Australian economic evaluation and government decisions on pharmaceuticals, compared to assessment of other health technologies. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:563–581. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond M, Jonsson B, Rutten F. The role of economic evaluation in the pricing and reimbursement of medicines. Health Policy. 1997;40:199–215. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(97)00901-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsinga E, Rutten FF. Economic evaluation in support of national health policy: the case of The Netherlands. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:605–620. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00400-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Pen C. Pharmaceutical economy and the economic assessment of drugs in France. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:635–643. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00402-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison DT, Mosley WH, Measham AR, Bobadilla JL. Disease control priorities in developing countries. New York, Oxford University Press. 1993.

- World Bank World development report 1993: Investing in health. New York, Oxford University Press. 1993.

- Adam T, Evans DB, Koopmanschap MA. Cost-effectiveness analysis: can we reduce variability in costing methods? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19:407–420. doi: 10.1017/S0266462303000369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutubessy RCW, Baltussen RMPM, Tan Torres-Edejer T, Evans DB. Generalised cost-effectiveness analysis: an aid to decision making in health. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy. 2002;1:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan P. The measurement of individual utility and social welfare. J Health Econ. 1998;17:39–52. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(97)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Evans DB, Acharya A, Baltussen RM. Development of WHO guidelines on generalized cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Econ. 2000;9:235–251. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(200004)9:3<235::AID-HEC502>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinnett AA, Paltiel AD. Mathematical programming for the efficient allocation of health care resources. J Health Econ. 1996;15:641–653. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(96)00493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff A. QALYs and the equity-efficiency trade-off. J Health Econ. 1991;10:21–41. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(91)90015-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon J, Welch HG. Priority setting: lessons from Oregon [see comments] Lancet. 1991;337:891–894. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tengs TO, Adams ME, Pliskin JS, Safran DG, Siegel JE, Weinstein MC, Graham JD. Five-hundred life-saving interventions and their cost-effectiveness [see comments] Risk Anal. 1995;15:369–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1995.tb00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Frenk J. A framework for assessing the performance of health systems. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:717–731. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwatkin DR. The need for equity-oriented health sector reforms. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:720–723. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.4.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwatkin DR. How well do health programmes reach the poor? Lancet. 2003;361:540–541. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12558-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James C, Carrin G, Savedoff W, Hanvoravongchai P. Using criteria to prioritize health interventions: implications for low-income countries. Geneva, World Health Organization WHO/HFS. 2003. Ref Type: Unpublished Work.

- World Health Organization The World Health Report 2002: Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. Geneva, World Health Organization. 2002.

- Making choices in health : WHO guide to cost-effectiveness analysis. Geneva, World Health Organization. 2003.

- Lauer JA, Rohrich K, Wirth H, Charette C, Gribble S, Murray CJL. PopMod: a longitudinal population model with two interacting disease states. Cost-effectiveness and Resource Allocation. 2003;1 doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam T, Aikins M, Evans D. CostIt software http://www.who.int/evidence/cea

- Hutubessy RC, Baltussen RM, Evans DB, Barendregt JJ, Murray CJ. Stochastic league tables: communicating cost-effectiveness results to decision-makers. Health Econ. 2001;10:473–477. doi: 10.1002/hec.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltussen RM, Hutubessy RC, Evans DB, Murray CJ. Uncertainty in cost-effectiveness analysis. Probabilistic uncertainty analysis and stochastic league tables. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2002;18:112–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Commission on Macroeconomics and Health Macroeconomics and health: investing in health for economic development. Report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health: Executive Summary. Geneva, World Health Organization. 2001.

- Evans DB, Tandon A, Murray CJ, Lauer JA. Comparative efficiency of national health systems: cross national econometric analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:307–310. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7308.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL, Lauer JA, Hutubessy RC, Niessen L, Tomijima N, Rodgers A, Lawes CM, Evans DB. Effectiveness and costs of interventions to lower systolic blood pressure and cholesterol: a global and regional analysis on reduction of cardiovascular-disease risk. Lancet. 2003;361:717–725. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutubessy RCW, Baltussen RMPM, Tan Torres-Edejer T, Evans DB. WHO-CHOICE: Choosing interventions that are cost-effective. In: Murray CJL, Evans DB, editor. Health system performance assessment: debate, new methods and empiricism. Geneva, World Health Organization, (forthcoming); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Witter S. Setting priorities in health care. In: Witter S, Ensor T, Jowett M, Thompson R, editor. Health economics for developing countries: a practical guide. London and Oxford, Macmillan Education Ltd; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaranayake L, Walker D. Cost-effectiveness analysis and priority setting: global approach without local meaning? In: Lee K, Buse K, Fustukian S, editor. Health policy in a globalising world. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 140–156. [Google Scholar]

- Paalman M, Bekedam H, Hawken L, Nyheim D. A critical review of priority setting in the health sector: the methodology of the 1993 World Development Report. Health Policy Plan. 1998;13:13–31. doi: 10.1093/heapol/13.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer JS. Economic analysis for health projects. Policy Research Working Paper No 611 Washington, DC, The World Bank. 1996.

- Bryan S, Brown J. Extrapolation of cost-effectiveness information to local settings. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1998;3:108–112. doi: 10.1177/135581969800300209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody JW, Omar Rahman M, Gertler PJ, Luck J, Carter GM, Farley DO. Policy and health; implications for development in Asia. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 1999.

- Baltussen R, Ament A, Leidl R. Making cost assessments based on RCTs more useful to decision-makers. Health Policy. 1996;37:163–183. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(96)90023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leidl RM. Some factors to consider when using the results of economic evaluation studies at the population level. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1994;10:467–478. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300006681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TH. Economics and cost-effectiveness in evaluating the value of cardiovascular therapies. What constitutes a useful economic study? The health systems perspective. Am Heart J. 1999;137:S67–S70. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power EJ, Eisenberg JM. Are we ready to use cost-effectiveness analysis in health care decision-making? A health services research challenge for clinicians, patients, health care systems, and public policy. Med Care. 1998;36:MS10–147. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugwell P, Bennett KJ, Sackett DL, Haynes RB. The measurement iterative loop: a framework for the critical appraisal of need, benefits and costs of health interventions. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38:339–351. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon JA, Murray CJL, Ustun B, Chatterji S. Health state valuations in summary measures of population health. In: Murray CJL, Evans DB, editor. Health systems performance assessment: debates, methods, and empiricism. Geneva, World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Musgrove P. Public spending on health care: how are different criteria related? Health Policy. 1999;47:207–223. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(99)00024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer JS, Berman P. End and means in public health policy in developing countries. Health Policy. 1995;32:29–45. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(95)00727-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPake B. The role of private sector in health service provision. In: Bennett S, McPake B, Mills A, editor. Private health providers in developing countries. Serving the public interest? London/New Jersey, Zedbooks; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AH, Gray AM. Handling uncertainty when performing economic evaluation of healthcare interventions. Health Technol Assess. 1999;3:1–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D, Fox-Rushby JA. Economic evaluation of communicable disease interventions in developing countries: a critical review of the published literature. Health Econ. 2000;9:681–698. doi: 10.1002/1099-1050(200012)9:8<681::AID-HEC545>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. Cost and cost-effectiveness of HIV/AIDS prevention strategies in developing countries: is there an evidence base? Health Policy Plan. 2003;18:4–17. doi: 10.1093/heapol/18.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]