Abstract

A microchip patterned with arrays of single cancer cells can be an effective platform for study of tumor biology, medical diagnostics, and drug screening. However, patterning and retaining viable single cancer cells on defined sites of the microarray can be challenging. In this study we used a tumor cell-specific peptide, chlorotoxin (CTX), to mediate glioma cell ahdesion on arrays of gold microelectrodes and investigated the effects of three surface modification schemes for conjugation of CTX to the microelectrodes on single cell patterning, which include physical adsorption, covalent bonding mediated by N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), and covalent bonding via crosslinking succinimidyl iodoacetate and Traut’s (SIA-Traut) regents. The CTX immobilization to microelectrodes was confirmed by high-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Physically adsorbed CTX showed better support for cell adheison and is more effective in confining adhered cells on the electrodes than covalently-bound CTX. Furthermore, cell adhesion and spreading on microelectrodes were quantified in real-time by impedance measurements, which revealed an impedance signal from physically adsorbed CTX electrodes four times greater than the signal from covalently-bound CTX electrodes.

Introduction

Cancer lesions are comprised of highly complex and diverse cell populations with great cell-to-cell variability in gene expression and biomarker presentations.1 Single-cell biosensors make it possible to study heterogeneous properties of cells in a population that are otherwise masked within the averaged response of the population.2 One promising platform for this purpose is an integrated microelectrode array (IMA) sensor addressable optically and electronically.3 These sensors are capable of continuous, automated analysis of individual cells and can quantitatively detect cellular events such as adhesion, spreading, growth, and migration.4 This is accomplished by monitoring electric signal alternations at the point of contact between the cell and microelectrode.3, 5 Yet, the development of such an IMA biosensor with cancer cells has proved to be more challenging than the sensors that are based on non-cancerous cells. This is largely due to the highly invasive or mobile nature of cancerous cells that makes patterning and further confining single cells on invididual electrodes particularly difficult. Additionally, to achieve optimal cell signal detectability, cells must spread across the entire electrode surface.6 Cell adhesion to IMA electrodes is governed by the cell-material interactions at the point of contact, and retaining viability and function of the patterned cells is essential for any patterning techniques and to the success of single-cell based IMA sensors.7

In this study, to create microarrays of single glioma cells on IMA sensors, we used a tumor cell-specific peptide, chlorotoxin (CTX), to mediate the natural adhesion of glioma cells on gold microelectrodes. Gliomas are the most deadly form of brain tumors, highly invasive, and known for their ability to migrate to nontumorous regions of the brain.8, 9 CTX, a 36 amino acid peptide derived from scorpion venom, binds to glioma tumor cells with high affinity.10, 11 CTX was immobilized on microelectrode surfaces by either physical adsorption, covalent bonding mediated by N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester, or covalent bonding via crosslinking succinimidyl iodoacetate and 2-Iminothiolane-HCl (SIA-Trauts) reagents. The NHS mediated bonding is more straightforward and simple, but offers limited control over the moleuclar orientation of attached CTX.12 The SIA-Traut mediated bonding is a two-step reaction but offers more control over the molecular orientation of CTX.

We investigated the influence of the binding method on cell patterning efficiency and behavior of patterned cells. The CTX binding on microelectrodes was characterized with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Single-cell adhesion and morphology and the effect of electrode size on the degree of cell spreading was examined by differential interference contrast (DIC) reflectance microscopy. Glioma cell attachment to the various CTX-modified electrodes and cell viability were quantified with the Alamar Blue assay. Finally, single-cell impedance monitoring was used to characterize the cell adhesion, spreading, and longevity in real-time.

Experimental

Materials

The following materials and chemicals were used as received: Remover PG (MicroChem, Newton, MA); Nano-Strip™ 2X (Cyantek, Fremont, CA); cysteamine, 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid 95% (11-MUA), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), N-hydroxysuccinimide 97% (NHS), 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)-propyl) carbodiimide (EDAC), medium molecular-weight chitosan, poly-L-lysine (Hydrochloride), and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), (Sigma-Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI); Succinimidyl iodoacetate (SIA) and 2-Iminothiolane-HCl (Traut’s reagent) (Molecular Biosciences, Boulder, CO); 2-[methoxy(polyethyleneoxy)propyl] trimethoxysilane (PEG) (Mw = 460–590 Da; Gelest, Morrisville, PA); Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), Opti-MEM® I Reduced-Serum Medium (O-MEM), 1X phosphate buffered saline solution (PBS), heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin-neomycin (PSN) antibiotic 100X mixture, TrypLE™ Express Stable Trypsin Replacement, fibronectin (bovine plasma), alamarBlue® (DAL 1100) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); lysine-arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (KRGD) oligopeptide (RS Synthesis, Louisville, KY); and Chlorotoxin (Alomone Labs Ltd., Jerusalem, Israel). All the solvents including toluene and triethylamine were HPLC grade and were purchased from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). Absolute ethanol was always deoxygenated by dry N2 before use. 9L cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA).

Surface modification

Arrays of gold microelectrodes were prepared on silicon oxide substrates following the procedure established previously13, 14, with minor modifications described herein. The protective photoresist layer on substrates was removed by Remover PG photoresist remover solution. The substrates were subsequently rinsed in isopropanol, ethanol, and DI water, respectively, immersed in Nano-Strip™ 2X piranha solution at room temperature for 30 min, rinsed with DI water, and dried with nitrogen. Before CTX conjugation, the piranha-treated substrates were modified by self-assembling either a cysteamine or 11-MUA monolayer on the gold electrodes of the substrates (both solutions at 20 mM concentration) for 16 hrs. The silicon oxide background of all the substrates were then passivated with PEG by immersing the substrates in 3 mM PEG and 1% triethylamine solution in anhydrous toluene at 60 °C for 18 hrs. Loosely bound moieties were removed from the surfaces by sonicating in toluene and ethanol for 5 min each, followed by rinsing with DI water and drying under nitrogen.

After PEG passivation, gold electrodes were chemically modified with CTX using one of three methods. For one group of substrates with 11-MUA modified surfaces, CTX physically adsorbed onto the electrodes at a concentration of 100 μg/mL in PBS of 8.2 pH at room temperature for 1 hr. The other two substrate groups were covalently-bound with CTX by one of two chemical schemes shown below.

One substrate group (Cov1) were covalently modified with CTX by immersing 11-MUA-modified substrates in an aqueous solution of 150 mM EDAC and 30 mM NHS for 30 min to attach the NHS ester intermediate to activate carboxylate groups of the alkanethiol SAM to chemically bond primary amine groups of CTX, where the lysine residues displace the NHS group during the reaction.15 These substrates were then exposed to a CTX peptide solution at a CTX concentration of 100 μg/mL in PBS buffer of 8.2 pH at room temperature for 1 hr.

Another substrate group (Cov2) were covalently modified with CTX in the following steps: the cysteamine-modified substrates were immersed in a solution of 3.5 mM SIA dissolved in thiolation buffer (100 mM PBS with 2 mM EDTA at 8.0 pH) for a 1 hr at room temperature, and concurrently 10 mg/mL Traut’s reagent were reacted with 500 μg/mL CTX at a molar ratio of 1:1 (both in Thiolation buffer) for 1 hr at predetermined volumes. The iodoacetate-functionalized SIA-cysteamine modified substrates were then rinsed with Thiolation buffer, and the resulting Traut’s-CTX solution was diluted to a final concentration of 100 μg/mL prior to reacting with the substrates for 1 hr at room temperature. Finally, all CTX-modified substrates were rinsed in their original solvents (PBS or Thiolation buffer) and DI water, respectively, to remove loosely bound moieties.

Cell culture and imaging on CTX-modified substrates

Rat glioma (9L) cell line was cultured in 75 cm2 flasks at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere. DMEM cell culture medium containing 10% FBS and 1% PSN antibiotic supplements was changed every third day for 9L cell passaging. For cell adhesion, 0.5 mL of 9L cells at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/mL with the cell numbers optimized to the total electrode surface area was plated onto each CTX-modified substrate. The cells were allowed to adhere to the substrates for 24 hrs under the standard culture conditions. For optical imaging using differential interference contrast (DIC) reflectance microscopy, cells were fixed with Karnovsky’s fixative (2% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS) for 60 min at room temperature. DIC images were acquired using a Nikon E800 upright microscope, (Nikon, Melville, NY).

XPS analysis of CTX-modified substrates

XPS spectra were taken on CTX-modified substrates using a PHI Versaprobe system. Pressure in the analytical chamber during the spectral acquisition was less than 5 × 10−8 Pascal. C1s, N1s, O1s, I3d3 and Au4f spectra were taken at 58.7 eV pass energy with 0.1 eV energy step and 50 ms per step. The takeoff angle (the angle between the sample normal and the input axis of the energy analyzer) was 45° (= 30 Å sampling depth). Igor Pro program was used to determine peak areas, calculate the elemental compositions, and peak-fit the high-resolution spectra. The binding energy scales of all elements were calibrated to Au4f peak, which was assigned to 84.0 eV.

Cell adhesion assay

9L cells were detached from 75 cm2 flasks and counted to bring to an initial concentration of 2 × 105 cells/mL for cell patterning over CTX-modified gold substrates placed into wells of a 24-well plate (1 mL/well, based on the gold surface area). After a 24 hrs of incubation at 37 °C to allow for cell attachment, a 10% Alamar Blue solution in phenol-free media was used to replace the previous cell seeding medium for a 4-hr incubation period at 37 °C. As a negative control, 10% Alamar Blue media was added to wells without cells. The fluorescence intensity was measured using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices) at excitation wavelength of 550 nm and emission wavelength of 590 nm. All data was plotted against a standard curve of percent Alamar Blue reduction, where linear regression analysis was carried out to determine a > 98% R2 value. Experiments were repeated two more times.

Impedance characterization of patterned cells

Electrical measurements of cells on the CTX-modified electrodes were recorded using a previously established IMA impedance platform.6 3.0 mL of 9L cells at a concentration of 2 × 104 cells/mL (based on total electrode surface area for IMA impedance chips) in O-MEM culture medium was plated onto each of the CTX-modified IMA substrates. Electrical measurements were recorded at the onset of cell seeding and throughout the seeding process. The input signal of a 10 mV (peak-to-peak) sine wave at 2 kHz frequency was passed through a 100 kΩ resistor in a voltage divider circuit configuration to limit the current amplitude to 100 nA. Electrical characterization involved the measurement of the voltage amplitude between the detecting electrode and counter electrode (ΔV) and the signal phase shift (Δϕ) using a SR810 lock-in amplifier. Complex impedance was calculated and analyzed post processing from the measured output voltage using MATLAB® software.

Results and Discussion

Surface modification chemistry on microelectrodes

CTX as an adhesion ligand was explored in order to adhere single 9L glioma cells to predefined locations on a patterned microelectrode array substrate. Physical adsorption (PA) and two covalent attachment methods (Cov1 and Cov2) were used to bind CTX to gold electrodes as illustrated in Fig. 1. In each case, a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) was produced to cover the surface of gold electrodes, while the silicon oxide background was passivated with a methoxy-PEG-silane layer. The PEG monolayer served to repel the protein and peptide adsorption.16

Fig. 1.

Illustration of surface modification of gold electrodes with CTX by three conjugation methods: (a) covalent bonding mediated by NHS (Cov1), (b) covalent bonding mediated by SIA-Traut (Cov2), and (c) physical adsorption (PA).

CTX binding by Cov1 scheme (Fig. 1a) involves the cross-linking of carboxylate groups on 11-MUA with primary amide functional groups on CTX via the NHS ester intermediate to form a stable amide bond. Specifically, CTX was covalently linked to NHS-SAM surfaces via the N-terminal α-amino group or the ε-amino group of the lysine side chain.17

CTX binding by Cov2 scheme (Fig. 1b) involves a three-step reaction. An amide-terminated thiol SAM (cysteamine) served as the base monolayer over the electrode surface and reacted with a heterobifunctional cross-linking reagent SIA to make a sulfhydryl reactive surface. CTX was chemically bound with Traut’s reagent at a stoicheometric ratio of 1:1 (CTX:Traut’s) to ensure that each CTX molecule has a singular, free sulfhydryl group to conjugate to the SIA monolayer. The main difference between the two covalent conjugation schemes is that Cov1 is more likely to link a CTX molecule by multiple binding sites (i.e. multiple NHS terminuses can cross-link three lysine amino acids per single CTX), while Cov2 used a molar ratio designed to link one Traut’s molecule to one CTX peptide, and subsequently to a single SIA terminus.

Fig. 1c represents CTX that is physically adsorbed (PA) to 11-MUA alkanethiol carboxylate. CTX would adsorb to the SAM interface of the gold surface in a nonspecific and noncovalent manner, i.e. through a combination of hydrogen bonding, electrostatic, and hydrophobic interactions.18 However, since the carboxylate terminus of 11-MUA has a net negative charge and chlorotoxin has a net positive charge,19 it is expected that electrostatic interaction plays a primary role in the CTX adsorption.

XPS characterization of CTX modification

XPS is well-established method to characterize the peptide adsorption and binding (within 10 nm of depth) onto surfaces.20 XPS analysis was carried out to determine the presence, relative amount, and binding of CTX on the substrates modified by the three binding schemes shown above. Fig. 2 shows high-resolution XPS spectra of C1s for Cov1, Cov2, and PA CTX-modified gold electrodes. Curve fitting of XPS high-resolution C1s spectra revealed the functional composition of the carbon species, demonstrating varying intensities of C=O, C–O/C–N, and C–C/C–H bonding as the C1s peak shifted for each sample. Cov2 CTX substrates exhibited the largest C–O/C–N peak centered at binding energy 286 eV (Fig. 2b), indicating the most bound CTX as CTX contains amide bonds (C–N) between amino acids and additional amide bonds along various side chains. Cov1 CTX substrates also exhibited a relatively large C–O/C–N peak (Fig. 2a), but not has pronounced as Cov2. PA CTX substrates revealed the smallest C–O/C–N peak and the largest C–C/C–H peak (centered at 285 eV) (Fig. 2c), which suggests sparse coverage of CTX over the 11-MUA-modifed surface.

Fig. 2.

High resolution XPS scans of carbon peaks for CTX on gold electrodes immobilized by (a) Cov1, (b) Cov2, and (c) PA schemes. Black dots represent the acquired spectral data from each sample. The black waveform represents the fitted curve based on the individual bonding peaks C=O (blue), C–O/C–N (green), and C–C/C–H (red).

To confirm that covalent bonding was formed for Cov1 and Cov2 conjugation schemes, high-resolution scans of N1s and I3d3 peaks were performed (Fig. 3). For the samples modified with Cov1 scheme, the XPS spectra of substrates modified with 11-MUA and NHS ester was compared to the spectra of substrates after completing the final step of CTX conjugation (Fig. 1a). Without conjugation of CTX to the NHS-terminated surface, the presence of N–O bonding was found at 402 eV (Fig. 3a) representing unreacted NHS ester. This peak was absent for samples conjugated with CTX by Cov1 scheme, indicating the covalent bonding of the peptide. For the sample modified with Cov2 scheme, the XPS spectra of substrates modified with a cysteamine monolayer linked with SIA was compared to the spectra of substrates after completing the final step of SIA-Traut’s mediated CTX conjugation. Without conjugation of CTX to the SIA-terminated surface, the iodine peak at 619 eV indicates the presence of SIA. After completing the last step of the CTX conjugation (Fig. 1b), iodine is cleaved from SIA and replaced by a C–S bond from the Traut’s reagent. Thus, the covalent linkage of Traut’s-CTX to SIA-terminated cysteamine can be interpreted from the absence of detected iodine at 619 eV binding energy (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

(a) Comparison of N1s high-resolution scans with fitted N–C (green) and N–O (blue) bonding peaks for Cov1 binding scheme without CTX (labeled “NHS”, bottom) and Cov1 scheme with CTX (labeled “Cov1”, top). Black dots represent the acquired spectral data, and the black waveform represents the fitted peak for each sample. (b) Comparison of high resolution scans of I3d3 peak for Cov2 scheme with CTX (labeled “Cov2”, black) and without CTX (labeled “SIA”, red), where both waveforms represent the acquired spectral data.

Cell adhesion quantification on CTX-modified substrates

To assess the effect of CTX on the cell adhesion, 200,000 9L cells were plated on each gold surfaces modified with CTX by either Cov1, Cov2, or PA method, and the gold surface without CTX was also included in the experiment. The cells were allowed to adhere for 24 hrs after seeding. The substrates were then rinsed, and the total number of viable cells remaining on the substrates were determined by the Alamar Blue assay.21 The cell count for each group was normalized to the initial seeded cells (Fig. 4). The surface modified with CTX by PA scheme supported highest cell adhesion, with 78% of seeded cells retained on the surface, followed by the surfaces modified by Cov1 (58%) and Cov2 (55%) schemes. On the surface without CTX, only 5% of seeded cells remained. This result indicates that CTX is effective in mediating glioma cell adhesion, and the way CTX is bound to the surface plays a signficant role in cellular behavior. PA CTX substrates exhibited better capability at adhering 9L than covalent CTX (e.g., 42% more cells on average). This might be due to the fact that the bioactivity of CTX via covalent attachment is lower than that of CTX via physical adsorption. The CTX with high bioactivity is expected to have high affinity to 9L cells.

Fig. 4.

Quantitative cell adhesion analyses using Alamar Blue assay for 9L cells 24 hr after seeding on gold substrates modified without CTX and with CTX through Cov1, Cov2, and physically adsorption schemes.

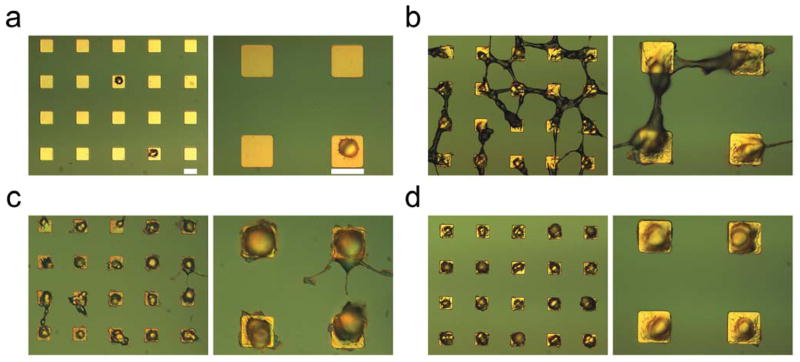

Glioma single-cell patterning on CTX-modified microelectrodes

To study the effect of various CTX conjugation schemes on the cell adhesion, spreading, and confinement to the electrode surfaces, 9L glioma cells were seeded on CTX modified microarrays of gold electrodes. Fig. 5 shows both low (left) and high (right) magnification DIC images of a typical microarray of patterned 9L cells on gold square electrodes (of 400 μm2 surface area that are spaced 40 μm apart) without CTX modification (Fig. 5a), with covalently attached CTX using Cov1 (Fig. 5b) or Cov2 (Fig. 5c) methods, or with physically adsorbed CTX (Fig. 5d). The microarrays without CTX were seen to have poor single-cell adherence, leaving most of the electrodes unoccupied. Conversely, electrodes with physically adsorbed CTX exhibited highly uniform patterns of single-cell adhesion and confinement to the electrodes (Fig. 5d). Yet, simply the presence of CTX on electrodes would not necessarily warrant a robust pattern of individual well-spread and confined cells. The glioma cells patterned on the substrates with covalently-bound CTX demonstrated cell morphology extended beyond the gold electrodes (Fig 5b–c). Similar cell morphology was also observed when 9L glioma cells were patterned on substrates where gold electrodes were functionalized using the common cell adhesion ligands, such as chitosan, fibronectin, poly-L-lysine, and RGD22, 23 (Fig. S1 in ESI). Glioma cells adhesion to these electrodes were typically fewer than those on CTX-modified electrodes, but more than those on the subsrates without adhesion ligands at all. Like the substrates with covalently-bound CTX, cell adhesion and spreading was not very well confined to the electrodes modified with chitosan, fibronectin, poly-L-lysine, or RGD. These results highlight the signficant role of CTX on mediating glioma cell adhesion and thus on the cell coverage (fraction of electrodes occupied by cells).

Fig. 5.

Optical DIC micrographs of 9L single-cell patterning 24 hr after seeding on 20 μm square gold electrodes modified with (a) no CTX (control), (b) covalently-bound CTX using NHS intermediary chemical scheme, (c) covalently-bound CTX using SIA-Traut intermediary chemical scheme, and (d) physically adsorbed CTX. In each panel, the right image is zoomed. The scale bars are 20 μm in all images, and spacing between the electrodes is 40 μm.

In the brain, glioma cells are capable of infiltrating throughout the brain tissue.24 This process involves the cell detachment from the primary tumor mass, ECM degradation, and cell elongation and migration that can span very long distances.25 The cellular morphological change shown on our covalent-bound CTX substrates (Fig. 5b–c), as well as substrates modified with common adhesion ligands like chitosan, fibronectin, poly-L-lysine, and RGD (Fig. S1 in ESI), demonstrated a similar trend and exhibited spontaneous elongation for migraton. It is believed that CTX targets the lipid raft that contains membrane-bound matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) protein complex with type 3 chloride channels (ClC-3), which ultimately prohibits the cell from making the necessary morphological changes for motility and contractility.24, 26

On our IMA sensor chips with the electrode surface modified with CTX using the PA method, glioma cells adhered and spread within the realm of each electrode. This desired morphology may be interpreted as a result of the affinity between the MMP-2 complex expressed by 9L and the CTX peptide that are bound to the gold surface. Although Cov1 chemical scheme showed good effect in attracting 9L to the electrode region, the cells were not immobilized and confined to the individual electrodes. It might be due to the inability to control the binding between CTX molecule and NHS-terminated SAM molecule in an one-to-one fashion. Conversely, Cov2 scheme was designed to control the binding of CTX through a single domain (from the Traut’s linker molecule). This binding formulation has been shown to inhibit glioma migration in vivo when linked to a nanoparticle.27 While CTX bound through Cov2 scheme showed improvement in immobilizing single 9L cells, it was not as effective as the CTX immobilized by PA scheme in producing consistent patterns. Despite the increased cell coverage on the electrodes (Fig. 5), both covalent binding schemes were unable to restrict single cells to the individual electrodes, and thus the amount of CTX is not as critical as the manner by which CTX is bound.

Having established that surface modification with PA CTX is the most effective approach to pattern single glioma cells on individual electrodes, the electrode sizes were investigated for optimal cell coverage. Fig. 6 shows images of typical 9L cells patterned on 10 μm, 15 μm, and 20 μm square electrodes. This result indicates that the 15 μm and 20 μm electrodes are best suitable for single glioma cell patterning. Cell patterning is a two-step process that involves cell attachment to the surface and spreading over the adhesion area. If the adhesion area is too small limiting the cell spreading, the attached cell tends to detach from the surface, as can be seen for some of the 10 μm sized electrodes (Fig. 6a). A larger adhesion area is more likely to secure a cell by providing additional space for cell spreading, as for the case of the 15 μm and 20 μm electrodes (Fig. 6b–c).

Fig. 6.

Optical DIC micrographs of 9L single-cell patterned 24 hr after seeding on CTX-modified electrodes, through physical adsorption, of (a) 10 μm, (b) 15 μm, and (c) 20 μm sizes. In each panel, the right image is zoomed. The scale bars are 20 μm in all images, and spacing between the electrodes is 40 μm.

Glioma cell impedance response on CTX-modified electrodes

Finally, to quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of CTX-mediated single-cell patterning on a microship, we analyze the degree of glioma cell attachment and spreading (and potential motility) using an electrical impedance system on our IMA chip. Cell impedance analysis has become a valuable characterization technique for detection and examination of cellular responses to chemical and biological agents in real-time for cytotoxicity studies and drug screening applications.3, 6 In this study, cell impedance analysis was used to provide further insight into the cell adhesion kinetics, morphology change, and detachment in response to the CTX-modified electrodes. Fig. 7 shows the normalized real impedance waveforms of a single 9L cell and the average of 9L single-cells on 30 μm detecting electrodes modified by the three CTX conjugation schemes. Cell impedance data was recorded starting at the onset of cell seeding across each electrode and at every 10 min for 44 hrs and normalized to the impedance prior to cell seeding. Impedance changes shown in these graphs correspond to the degree of alteration in cell–electrode coverage. The electrical current flowing through the cell–electrode–electrolyte pathway at the chosen 2 kHz frequency is paracellular due to the insulative properties of the cell. This means that current has to bypass the cell along shunt pathways, e.g., through narrow channels that exist between the cell and electrode surface and along the pathways that may exist around the cell into the bulk electrolyte.28 Thus, tighter adhesion and greater cell spreading reduces the space of these shunt pathways, in turn yielding a much larger cell impedance SNR.29

Fig. 7.

(a) Normalized real impedance waveforms of three 9L cell on PA, Cov1, and Cov2 CTX-modified 30 μm electrodes, respectively, monitored over a period of 44 h. (b) Averaged values of normalized single-cell real impedance (n = 10) for cells on the three substrates described in (a). Real impedance was normalized to the impedance prior to cell seeding.

From the impedance responses of three representative single cells on three substrates that were CTX-modified through PA, Cov1 and Cov2, respectively (Fig. 7a), we observed that the adhesion occurred in a relatively similar fashion during the first 4 hrs for all three cells, each yielding a real impedance magnitude ~2× greater than that prior to cell seeding (0 hr). However, the difference in impedance response was evident after this time point. The glioma cell impedance on the PA CTX electrode continued to rise considerably throughout the first 24 hrs, signifying continued cell spreading over the electrode. On the other hand, the impedance of the glioma cell on Cov2 CTX electrode peaked between 20 and 24 hrs at a magnitude 54% that of the cell on the PA CTX electrode and began to decline over the remaining period of impedance monitoring. The dramatically reduced impedance suggested the cell migration and eventual detachment from the electrode upon the attachment to a neighboring electrode on the IMA chip, which was verified by microscopy (image not shown).

Similar behavior was demonstrated by the 9L cell on the Cov1 CTX electrode, where the cell adhered and attempted to migrate without completely vacating the electrode (images not shown). While Fig. 7a shows the responses of three representative cells from three differently-modified electrodes, Fig. 7b shows averaged impedance reponses of 10 cells on each electrode array of the same cell population. After 24 hrs, the averaged impedance response of 9L cells on PA CTX electrodes was dramatically different from those on Cov1 and Cov2 CTX electrodes. Their average impedance signals remained high by the end of the experiment, indicating that this technique is effective in identifying key cellular events, such as attachment, morphology change, and migration with great sensitivity and temporal resolution in real time and a quantitative manner.

Conclusions

We presented three conjugation schemes to attach the high affinity tumor binding ligand chlorotoxin to microelectrodes for patterning highly motile single glioma cells. Our study demonstrated that physically adsorbed CTX on microelectrodes best supported glioma single-cell adhesion and spreading on IMA electrodes. Using single-cell impedance monitoring, glioma cell attachment, spreading, and migration can be quantitatively assessed in real-time. Our approach of using CTX as an adhesion ligand to pattern single cells is effective in producing large arrays of individual canerous cells with high fidelity. However, the CTX-mediated cell adhesion would not be effective in binding normal, noncancerous cells that do not express MMP-2. In addtion, CTX is costly compared to commonly-used adhesion ligands. The microarrays of single cancer cells developed in this study can be potentially used to study tumor biology and anti-cancer drug screening.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the funding support from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM075095) and lab assistance of Johnson Tey, Kandy Yeung, Sandy Yung, and YuChun Chen.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Fig. S1. 9L single-cell patterned on gold electrodes modified with chitosan, fibronectin, poly-L-lysine, and RGD. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Hanash SM, Pitteri SJ, Faca VM. Nature. 2008;452:571–579. doi: 10.1038/nature06916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levsky JM, Singer RH. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:4–6. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asphahani F, Zhang M. Analyst. 2007;132:835–841. doi: 10.1039/b704513a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luong JHT. Analytical Letters. 2003;36:3147–3164. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovacs GTA. Proceedings Of The Ieee. 2003;91:915–929. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asphahani F, Wang K, Thein M, Veiseh O, Yung S, Xu J, Zhang M. Physical Biology. 2011;8 doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/8/1/015006. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen CS, Jiang XY, Whitesides GM. MRS Bull. 2005;30:194–201. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huse JT, Holland EC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:319–331. doi: 10.1038/nrc2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norden AD, Drappatz J, Wen PY. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:610–620. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deshane J, Garner CC, Sontheimer H. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4135–4144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McFerrin MB, Sontheimer H. Neuron Glia Biol. 2006;2:39–49. doi: 10.1017/S17440925X06000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veiseh O, Gunn JW, Zhang MQ. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:284–304. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veiseh M, Veiseh O, Martin MC, Asphahani F, Zhang MQ. Langmuir. 2007;23:4472–4479. doi: 10.1021/la062849k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veiseh M, Zhang M. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1197–1203. doi: 10.1021/ja055473q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veiseh M, Wickes BT, Castner DG, Zhang M. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3315–3324. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veiseh M, Zareie MH, Zhang MQ. Langmuir. 2002;18:6671–6678. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laskin J, Wang P, Hadjar O. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2008;10:1079–1090. doi: 10.1039/b712710c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horbett TA, Brash JL. Acs Symposium Series. 1987;343:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhawan R, Joseph S, Sethi A, Lala AK. FEBS Lett. 2002;528:261–266. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lhoest JB, Detrait E, van den Bosch de Aguilar P, Bertrand P. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;41:95–103. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199807)41:1<95::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez GC, Haisley C, Hurteau J, Moser TL, Whitaker R, Bast RC, Stack MS. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80:245–253. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.6042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anamelechi CC, Clermont EC, Novak MT, Reichert WM. Langmuir. 2009;25:5725–5730. doi: 10.1021/la803963r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wan ACA, Tai BCU, Schumacher KM, Schumacher A, Chin SY, Ying JY. Langmuir. 2008;24:2611–2617. doi: 10.1021/la7025768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sontheimer H. Exp Biol Med. 2008;233:779–791. doi: 10.3181/0711-MR-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tate MC, Aghi MK. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6:447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veiseh O, Kievit FM, Fang C, Mu N, Jana S, Leung MC, Mok H, Ellenbogen RG, Park JO, Zhang MQ. Biomaterials. 2010;31:8032–8042. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veiseh O, Gunn JW, Kievit FM, Sun C, Fang C, Lee JSH, Zhang MQ. Small. 2009;5:256–264. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thein M, Asphahani F, Cheng A, Buckmaster R, Zhang MQ, Xu J. Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 2010;25:1963–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asphahani F, Thein M, Veiseh O, Edmondson D, Kosai R, Veiseh M, Xu J, Zhang MQ. Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 2008;23:1307–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.