Abstract

Hydatid disease caused by tapeworm is an increasing public health and socioeconomic concern. In order to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of praziquantel (PZQ) against tapeworm, PZQ-loaded hydrogenated castor oil solid lipid nanoparticle (PZQ-HCO-SLN) suspension was prepared by a hot homogenization and ultrasonication method. The stability of the suspension at 4°C and room temperature was evaluated by the physicochemical characteristics of the nanoparticles and in-vitro release pattern of the suspension. Pharmacokinetics was studied after subcutaneous administration of the suspension in dogs. The therapeutic effect of the novel formulation was evaluated in dogs naturally infected with Echinococcus granulosus. The results showed that the drug recovery of the suspension was 97.59% ± 7.56%. Nanoparticle diameter, polydispersivity index, and zeta potential were 263.00 ± 11.15 nm, 0.34 ± 0.06, and −11.57 ± 1.12 mV, respectively and showed no significant changes after 4 months of storage at both 4°C and room temperature. The stored suspensions displayed similar in-vitro release patterns as that of the newly prepared one. SLNs increased the bioavailability of PZQ 5.67-fold and extended the mean residence time of the drug from 56.71 to 280.38 hours. Single subcutaneous administration of PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension obtained enhanced therapeutic efficacy against tapeworm in infected dogs. At the dose of 5 mg/kg, the stool-ova reduction and negative conversion rates and tapeworm removal rate of the suspension were 100%, while the native PZQ were 91.55%, 87.5%, and 66.7%. When the dose reduced to 0.5 mg/kg, the native drug showed no effect, but the suspension still got the same therapeutic efficacy as that of the 5 mg/kg native PZQ. These results demonstrate that the PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension is a promising formulation to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of PZQ.

Keywords: pharmacokinetics, hydatid disease, Echinococcus granulosus

Introduction

Hydatid disease is a cause of substantial morbidity and mortality in most of the world, including parts of Europe, North America, South America, Asia, and Africa.1–3 It is a chronic cyst-forming parasitic helminthic disease of human beings as well as domestic and wild ungulates.4 This disease can result in a 10% decrease in whole of life performance for infected animals (reduction in quality of meat, production of fiber, production of milk, and the number of surviving offspring).5 Dogs are the definitive hosts that harbor the adult stage of the parasite, thus prophylaxis and therapy of tapeworm infection in dogs is the decisive step avoiding transmission of this disease to humans and livestock.4,6 Many programs have been implemented to remove the parasite in different countries/areas, such as continuous dosing of praziquantel (PZQ ) tablets or baits to dogs once or twice a week for years,7,8 but control of the transmission of tapeworm infection is very difficult. For example, it took New Zealand and Tasmania more than 30 years to eliminate the parasite infection following dog-targeted chemotherapy control.8 The program in Uruguay had little effect on livestock or human cystic echinococcosis rates over the first 20 years of the campaign.9 Epidemiologically, human cystic echinococcosis occurs predominantly in poor agricultural and pastoral communities.7 The poverty often relates to the failure of the community to adopt control measures. Therefore, achieving a high level of disease transmission control, reducing the cost of a control program, and increasing compliance from dog owners should be considered.

PZQ is one of the first-line anthelmintic drugs for treating tapeworm infections and has become the cornerstone for hydatid control campaigns worldwide.10 It has potent cestocidal activity against Taenia taeniaeformis, Echinococcus granulosus, Mesocestoides vogae, M. corti, Dipylidium caninum, and Hymenolepis diminuta in animals and humans.11,12 PZQ is highly effective on mature and immature tapeworm species tested in mice, rats, cats, dogs, and sheep.11 Although PZQ is a very effective anthelmintic, it is practically insoluble in water and has poor bioavailability because of extensive hepatic first-pass metabolism and rapid clearance from the bloodstream with a terminal elimination half-life (t½(el)) of 1–3 hours.13,14 Repeated administration of high dose PZQ over a long time for therapy of cestode infection is required. For example, the common usage of PZQ is up to 75 mg/kg per day for 15–20 days preoperatively for hydatid disease caused by Echinococcus spp.15 The dose of PZQ is 50 mg/kg/day for 15 days for the cysticercus stage of Taeniasolium, especially in its localization in the brain (neurocysticercosis).16 Frequent administration is not only time-wasting, but also costly. Moreover, repeated medication is too complex to efficiently achieve satisfactory mass control. The high daily dose might produce a slight transient disturbance in general wellbeing, such as tiredness, dizziness, nausea, and hangover feeling.17

To overcome these shortcomings, new strategies of delivery are necessary. Some researchers have developed the long-term sustained-release implantable PZQ-containing bar and PZQ-loaded sustained-release PCL implant.18,19 Liposomal formulations have also been prepared to improve the bioavailability, systemic circulation time, and cestocidal activity of PZQ.20,21

Previous studies demonstrate that solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) significantly prolong the systemic circulation time and increased the bioavailability of PZQ.22,23 The improved bioavailability and systemic circulation time of PZQ could enhance its therapeutic efficacy and reduce dose and administration frequency. SLNs are usually produced as either aqueous dispersions (suspensions) or dry powders. Suspensions are preferred with regard to the ease of handling (no reconstitution necessary) and for cost reasons (eg, cost of freeze drying).24 It has been reported that aqueous dispersions of SLNs were basically stable under the optimization of the storage conditions for up to 3 years; however, some systems show particle growth followed by gelation.24,25 Alternatively, the liquid can be converted into a dry product by spray drying or lyophilization to avoid occurring instabilities.24

In this work, a PZQ-loaded hydrogenated castor oil (HCO)-SLN (PZQ-HCO-SLN) suspension was prepared. The stability of the suspension was evaluated by physicochemical characteristics of the nanoparticles and in-vitro release property of the suspension. The pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy of the suspension were studied in dogs.

Materials and methods

Materials

HCO was purchased from Tongliao Tonghua Castor Chemical Co, Ltd (Inner Mongolia, China). PZQ reference standard was bought from China Institute of Veterinary Drug Control (Beijing, China). Native PZQ was obtained from Wuhan Kanglong Century Technology Development Co, Ltd (Wuhan, China). Poly vinyl alcohol (PVA) was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Methyl alcohol used for high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was of liquid chromatography grade, available from Tedia Company, Inc (Fairfield, OH). The water was prepared with a Millipore (Bedford, MA) Milli-Q® system.

Preparation of PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension

The PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension was prepared by the hot homogenization and ultrasonication method as described previously.23 Briefly, HCO (17 g) and PZQ (3 g) were added in a 250 mL beaker and put in a boiling water bath. After the lipid–drug mixture became a clear melting solution, 130 mL of boiling 1% PVA solution was poured into the lipid phase under magnetic stirring, and sonicated for 20 minutes with a VCX 750 Vibra-Cell™ (Sonics and Materials, Inc, Newtown, CT), using the 13 mm microprobe with amplitude 35%, to form a nanoemulsion. The hot nanoemulsion was cooled down to obtain a nanoparticle suspension. The control nanoparticle suspension was prepared in the same way without adding PZQ.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of SLNs

The morphology of nanoparticles was studied by SEM (SE S-3400N; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Briefly, 2 μL of the nanoparticle suspension was placed on a glass surface. After oven-drying, the samples were coated with gold using an ion sputter for 3 minutes and examined at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV.

Determination of drug recovery

To determine the drug recovery from the suspension, 0.2 mL suspension was added into a 15 mL tube containing 9.8 mL methyl alcohol. The tube was heated on a boiling water bath for 10 minutes and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm ( Centrifuge 5810 R; Eppendorf, Germany) for 25 minutes. The PZQ in the supernatant was measured by HPLC using a UV Detector at wavelength 215 nm (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). The control nanoparticle suspension without PZQ was treated similarly and used as blank for the measurements. The assay was repeated three times using different samples from independent preparations. Drug recovery is defined as follows:

| (1) |

Determination of diameter, polydispersity index, and zeta potential of SLNs

The diameter, polydispersity index, and zeta potential of nanoparticles was measured by photon correlation spectroscopy (PCS Zetasizer Nano ZS90; Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK). The nanoparticle suspension was diluted by 60 times for the determination of particle size and polydispersity index, and diluted by 360 times for zeta potential determination to get optimum kilo counts per second of 20–400 for measurements.

In-vitro release study

PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension (0.2 mL) was added in 1.8 mL 0.9% (w/v) sodium chloride (NaCl) solution (donor solution) in a dialysis bag (molecular weight: 8000–14,400) and dialyzed against 45 mL 0.9% (w/v) NaCl solution (receiver solution) in a 50 mL tube at 37°C under magnetic stirring at 100 rpm. At fixed times, the receiver solution was taken for PZQ quantitation by HPLC, and the dialysis bag was transferred to another 50 mL tube containing 45 mL fresh solution. The control nanoparticle formulation without PZQ was treated similarly and used as blank for the measurements. The experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Stability evaluation

Stability of the nanoparticle suspension was evaluated after the samples were stored at 4°C and room temperature for 4 months. The nanoparticle diameter, polydispersity index, and zeta potential, and the in-vitro release patterns, were used for the evaluation of the physical stability of the nanoparticle suspension. The assay was repeated three times using different samples from independent preparations.

Pharmacokinetic study

Xinjiang indigenous dogs (15–27 kg) were fed at the Veterinary Research Institute of Animal Science Academy of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. All experimental protocols concerning the handling of dogs were in accordance with the requirements of the experimental animal ethics/Ethics Committee at Animal Science Academy of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. The animals were housed at room temperature with free access to a standard diet and water. Before initiation of the experiment, ten healthy dogs were randomly divided into two groups, with five animals in each group. A single dose (5 mg/kg) of PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension or native PZQ suspended in 0.9% sterile NaCl at drug concentration of 2% (w/v) was then subcutaneously administered into the cervical area of the dogs. At different time points post injection, blood samples were taken from the vena cervicalis, and the drug levels in the plasma were assayed.

HPLC assay

PZQ concentrations in plasma were measured by HPLC. Sample extracts were prepared by mixing 1 mL plasma with 6 mL mixture of methyl tert-butyl ether and dichlormethane (2:1 v/v). The mixtures were vortexed for 3 minutes to allow complete mixing, followed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm (Sigma 1–14; Sartorius, Germany) for 25 minutes. The supernatant was then incubated in a fan-assisted oven (65°C, 30 minutes) and was dissolved in 300 μL mobile phase. A 100 μL aliquot was taken for HPLC analysis. Chromatographic conditions were as follows: reverse phase C18 column, VP-ODS, 250 mm × 4.6 mm ( Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan); mobile phase, acetonitrile/Milli-Q water (60/40, v/v); flow rate, 1.0 mL/min; column temperature, 20°C; and UV detector wavelength, 215 nm. The plasma concentration of PZQ was found to be linear over the range 5–2000 ng/mL. The correlation coefficient was 0.9999. The quantification limit of the method for PZQ in plasma was 5 ng/mL. The extraction recovery for the plasma PZQ from three concentrations (10, 100, and 500 ng/mL) was 89.1% ± 0.8%, 94.2% ± 3.6%, and 91.1% ± 1.2%, respectively. The relative standard deviations of accuracy and precision for three different plasma concentrations of PZQ (10, 100, and 500 ng/mL) were 4.5%, 0.6%, and 3.4%, respectively, for inter-day analysis, and 1.9%, 3.8%, and 1.3%, respectively, for intra-day analysis.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

The plasma concentrations versus time data were analyzed based on noncompartmental pharmacokinetics using PK Solutions 2.0 (Ashland, OH) software. The plasma drug concentrations over time data were used to calculate the area under the concentration–time curve (AUC0–∞) and the mean residence time (MRT) of the PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension and native PZQ.

Therapeutic trials

The therapeutic trials of PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension were performed in Xinjiang indigenous adult dogs naturally infected with E. granulosus. Fecal samples were taken from each dog pretreatment to confirm the E. granulosus infection by epidemiology survey, egg microscopy, and coproantigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay determination.26,27 Forty infected dogs were randomized into five treatment groups, with eight animals per group. Two drug doses (0.5 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg) in the form of either PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension or native PZQ suspended in 0.9% sterile sodium chloride at drug concentration of 2% (w/v) were subcutaneously administered into four groups of dogs. One untreated group was used as control. Fecal samples were taken daily from each animal for 1 week post-treatment. Samples were analyzed using the saturated sucrose flotation technique,28 and the number of eggs per gram of feces was calculated. At the end of the experiment, three dogs from each treatment were sacrificed and their intestines were examined for the presence of tapeworms. 11 If no tapeworm was found, they were considered as removed by the drug. The efficacy of the treatment was determined as stool-ova reduction rate,29 stool-ova negative conversion rate,30 and tapeworm removal rate.11

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where EPG is eggs per gram.

Statistical methods

The data on nanoparticle diameter, polydispersity index, zeta potential, and pharmacokinetic parameters of PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension and native PZQ suspension were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance. Significance was evaluated at P-value of 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (2003).

Results

Physicochemical characteristics of the SLNs

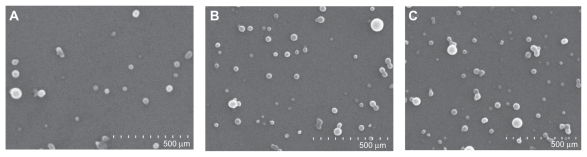

The drug recovery from the nanoparticle suspension was 97.59%. SEM studies showed that the nanoparticles were spherical with smooth surfaces and had no differences after 4 months of storage at 4°C and room temperature (Figure 1). The diameter, polydispersivity index, and zeta potential of nanoparticles displayed no significant changes after 4 months of storage at 4°C and room temperature as compared with that of the fresh preparation (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopy graphs of PZQ-HCO-SLN (65,000×): (A) Newly prepared SLNs, (B) SLNs stored at 4°C for 4 months; and (C) SLNs stored at room temperature for 4 months.

Abbreviations: PZQ-HCO-SLN, praziquantel-loaded hydrogenated castor oil solid lipid nanoparticle suspension; SLN, solid lipid nanoparticle.

Table 1.

The physicochemical characteristics of PZQ-HCO-SLN (mean ± SD, n = 3)

| Formulation | MD, nm | PDI | ZP, mV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newly prepared SLNs | 263.00 ± 11.15 | 0.34 ± 0.06 | −11.57 ± 1.12 |

| SLNs stored at 4°C | 256.00 ± 20.22 | 0.37 ± 0.05 | −10.87 ± 0.71 |

| SLNs stored at room temperature | 260.67 ± 19.22 | 0.36 ± 0.09 | −12.33 ± 0.81 |

Abbreviations: MD, mean diameter; PDI, polydispersity index; PZQ-HCO-SLN, praziquantel-loaded hydrogenated castor oil solid lipid nanoparticle suspension; SD, standard deviation; SLN, solid lipid nanoparticle; ZP, zeta potential.

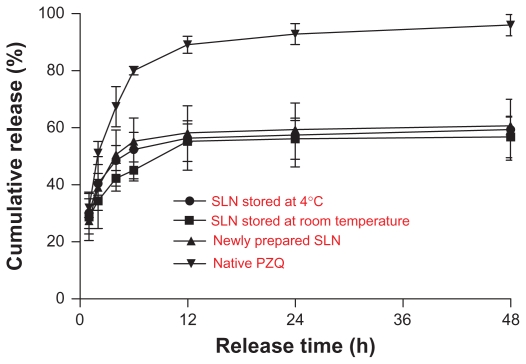

In-vitro release

The stored nanoparticle suspension displayed the same release pattern as that of the fresh preparation. In-vitro release curve of the SLN suspension exhibited a biphasic pattern with a fast release from 55.33% to 58.20% within the initial 12 hours, followed by a slow and sustained release (Figure 2). The amount of cumulated release over 48 hours was 56.79%–60.69%, and the daily release rate was lower than 0.5%. In contrast, the release rate of native PZQ suspension was much faster. The cumulative release was up to 91.03% by 12 hours. The release almost completed (96.00%) by 48 hours.

Figure 2.

In-vitro release of PZQ-HCO-SLN (mean ± SD, n = 3).

Abbreviations: PZQ, praziquantel; PZQ-HCO-SLN, praziquantel-loaded hydrogenated castor oil solid lipid nanoparticle suspension; SD, standard deviation; SLN, solid lipid nanoparticle.

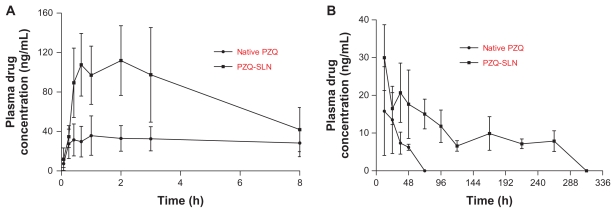

Pharmacokinetics

Plasma PZQ concentration–time curves are shown in Figure 3. The pharmacokinetic parameters are depicted in Table 2. After subcutaneous administration of native PZQ, the plasma drug concentration reached a peak level of 47.82 ng/mL at 1.45 hours, then decreased to the quantification limit (5 ng/mL) by 48 hours and was undetectable by 72 hours. In the HCO-SLN suspension group, PZQ reached a significantly higher peak concentration of 113.70 ng/mL at 1.93 hours and then decreased to the same level as that of native drug by 8 hours. The plasma drug concentration in the SLN group was higher than that of the native drug group again after 24 hours and maintained over 5 ng/mL for up to 264 hours. The plasma drug concentration was undetectable in the SLN group by 312 hours.

Figure 3.

Plasma PZQ concentration–time curves after a single dose of subcutaneous administration of PZQ-HCO-SLN and PZQ suspension (5 mg/kg) (mean ± S D, n = 5): (A) within 8 hours, (B) from 12 to 312 hours.

Abbreviations: PZQ, praziquantel; SLN, solid lipid nanoparticle.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of PZQ-HCO-SLN and PZQ suspension after subcutaneous administration in dog (mean ± SD, n = 5)

| Formulation | t½(ab), hours | t½(d), hours | t½(el), hours | tmax, hours | Cmax, ng/mL | MRT, hours | AUC0–∞, ng ·h/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PZQ-SLN | 0.31 ± 0.11 | 4.36 ± 1.81 | 189.62 ± 80.72a | 1.93 ± 1.09 | 113.70 ± 37.27a | 280.38 ± 116.41a | 5898.17 ± 2048.73a |

| Native PZQ | 0.97 ± 0.80 | 2.60 ± 0.79 | 34.53 ± 19.15 | 1.45 ± 1.07 | 47.82 ± 13.06 | 56.71 ± 23.41 | 1039.98 ± 149.19 |

Note: Statistical significances compared with native drug are P < 0.05.

Abbreviations: AUC0–∞, area under the concentration–time curve from zero to infinity; Cmax, maximal PZQ concentration in plasma; MRT, mean residence time; PZQ, praziquantel; PZQ-HCO-SLN, praziquantel-loaded hydrogenated castor oil solid lipid nanoparticle suspension; SD, standard deviation; SLN, solid lipid nanoparticle; t½(ab), absorption half-life; t½(d), distribution half life; t½(el), elimination half-life; tmax, time to reach Cmax.

The pharmacokinetic analysis revealed that t½(el) and MRT of PZQ-HCO-SLN were significantly longer than those of native PZQ (Table 2). Moreover, the AUC0–∞ and maximal PZQ concentration (Cmax) of the PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension was 5.67- and 2.38-fold higher, respectively, than those obtained with the native PZQ (Table 2).

Therapeutic efficacy

The therapeutic efficacy in dogs naturally infected with E. granulosus is shown in Table 3. At PZQ dose of 5 mg/kg, no egg was detected from the stool of dogs in the SLN group, while the stool-ova reduction and negative conversion rates in the native PZQ group were 91.55% and 87.5%, respectively. When the drug dose reduced to 0.5 mg/kg, the stool-ova reduction and negative conversion rates in the SLN group were 96.76% and 87.5%, but they dropped dramatically to 22.08% and 0% in the native PZQ group.

Table 3.

Stool-ova reduction and negative conversion, and tapeworm removal rates post-treatment

| Treatment | Dosage, mg/kg | Stool-ova reduction rate, % | Stool-ova negative conversion rate, % | Tapeworm removal rate, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PZQ-SLN | 5 | 100 ± 0 | 100 (8/8) | 100 (3/3) |

| PZQ-SLN | 0.5 | 96.76 ± 9.16 | 87.5 (7/8) | 66.7 (2/3) |

| Native PZQ | 5 | 91.55 ± 23.88 | 87.5 (7/8) | 66.7 (2/3) |

| Native PZQ | 0.5 | 22.08 ± 29.42 | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/3) |

| Untreatment | 0 | 13.89 ± 21.36 | 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/3) |

Abbreviations: PZQ, praziquantel; SLN, solid lipid nanoparticle.

Intestine examination showed that the tapeworm was only present in the stool-ova-positive dogs, therefore the tapeworm removal rates with different treatment were the same as that of the stool-ova negative conversion rates in the sacrificed dogs.

Discussion

The physicochemical characteristics of the nanoparticle suspension were similar to that of the freeze-dried PZQ-HCO-SLN prepared in the authors’ previous study, and the drug recovery from the nanoparticle suspension was high. Due to the presence of unincorporated drug in the suspension, the initial release rate of the PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension within 2 hours was faster than that of lyophilized PZQ-HCO-SLN, but the subsequent release was very similar to that of freeze dried nanoparticles.23 The results demonstrated that the PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension is an effective sustained-release formulation.

The nanoparticle diameter, polydispersivity index, zeta potential, and release pattern have always been used to evaluate the stability of nanoparticle suspensions.24,31 The HCO-SLN suspension did not have agglomeration, and the physicochemical characteristics had no significant changes after being stored at both 4°C and room temperature for 4 months, indicating the SLN suspension had good stability.

Subcutaneous administration of PZQ is one of the effective routes of cestode infection in animals.11,32 A previous study demonstrates that subcutaneous administration of PZQ-SLN is superior to oral and intramuscular routes for enhanced drug bioavailability and systemic circulation time.23 Therefore, the subcutaneous route was selected for pharmacokinetic study in this present work.

The PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension significantly extended the systemic circulation time and enhanced the bioavailability of PZQ. However, the Cmax of PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension was higher than that obtained with native PZQ, which is inconsistent with our previous study on lyophilized PZQ-HCO-SLN. This might be due to the free drug in the suspension, which could micronize or formulate pure drug nanoparticles in the preparation process, resulting in increased dissolution and swift absorption of the drug. In addition, the emulsifier could enhance the solubility of unentrapped drug, thus increasing the absorption rate of a drug at the injection site.33 Mass chemotherapy with PZQ can reduce the prevalence of tapeworm.34 However, the effect could only be sustained with continued regular use of PZQ baits. Once baiting ceases, animals become reinfected within a few months.34 The extended systemic circulation time of PZQ could decrease the dosage frequency, which is favorable to mass control of tapeworm infection.

E. granulosus prevalences are found in all continents and at least 100 countries.35 There are 22 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities in China reported with cystic echinococcosis, which is regarded as one of the major public health problems.36 In Xinjiang, the prevalence of cystic echinococcosis in humans, sheep, cattle, and dogs was 0.07–28.40, 6.10–100.00, 2.00–88.00, and 0–51.80, respectively. 36 In this study, dogs infected with E. granulosus were chosen to evaluate the anthelmintic activity of the SLN suspension using two PZQ doses. The high dose of 5 mg/kg was based on the clinic dosage.11 Subcutaneous administration of 5 mg/kg is effective in eliminating tapeworm from dogs.37,38 Considering the enhancement of pharmacological activity of PZQ by SLNs, a low dose of 0.5 mg/kg was also used to assess the therapeutic efficacy of the SLN suspension. At both doses, the stool-ova reduction and negative conversion rates and tapeworm removal rate indicate that the SLN suspension could significantly enhance the therapeutic efficacy and decrease the clinic dosage of PZQ. Since the cestocidal activity of PZQ is concentration- and time-dependent,11,21,28 exposure of the tapeworm to higher drug concentrations and/or longer time is essential for adequate treatment of parasite infection. In addition, the high drug concentration and long drug action time have a synergistic effect to enhance the cestocidal activity of PZQ.21 Based on the pharmacokinetics of the suspension and cestocidal mechanisms of PZQ, the enhanced cestocidal activity against other cestodes might be anticipated, but further studies need to be done to confirm its broad efficiency to treat tapeworm infections in most mammals.

Conclusion

The PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension has good stability stored at 4°C and room temperature. The SLN suspension significantly enhances the pharmacological activity and therapeutic efficacy of PZQ. The PZQ-HCO-SLN suspension would be a promising formulation for prophylaxis and therapy of tapeworm infection. The nanoparticle suspension would be an efficient alternative formulation for tapeworm transmission control.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Technology R&D Program in the 11th Five Year Plan of China (2006BAD04A16-41). The Earmarked fund for Modern Agro-insdustry Technology Research System. The Program for Cheung Scholar and Innovative Research Teams in Chinese Universities (No. IRT0866).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dakkak A. Echinococcosis/hydatidosis: a severe threat in Mediterranean countries. Vet Parasitol. 2010;174(1–2):2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anadol D, Özçelik U, Kiper N, Göçmen A. Treatment of hydatid disease. Paediatr Drugs. 2001;3(2):123–135. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200103020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romig T, Dinkel A, Mackenstedt U. The present situation of echinococcosis in Europe. Parasitol Int. 2006;55(Suppl 1):S187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenkins DJ. Echinococcus granulosus in Australia, widespread and doing well! Parasitol Int. 2006;55(Suppl 1):S203–206. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Battelli G. Evaluation of the economic costs of echinococcosis. Int Arch Hidatid. 1997;32:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig PS, Larrieu E. Control of cystic echinococcosis/hydatidosis: 1863–2002. Adv Parasitol. 2006;61:443–508. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)61011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gemmell MA, Lawson JR, Roberts MG. Control of echinococcosis/hydatidosis: present status of worldwide progress. Bull World Health Organ. 1986;64(3):333–339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craig PS, McManus DP, Lightowlers MW, et al. Prevention and control of cystic echinococcosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(6):385–394. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gemmell MA. Workshop summary: hydatid – new approaches. Vet Parasitol. 1994;54(1–3):295–296. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urrea-París M, Casado N, Moreno M, Rodriguez-Caabeiro F. Chemoprophylactic praziquantel treatment in experimental hydatidosis. Parasitol Res. 2001;87(6):510–512. doi: 10.1007/s004360100390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas H, Gönnert R. The efficacy of praziquantel against cestodes in animals. Z Parasitenk. 1977;52(2):117–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00389898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gemmell MA, Johnstone PD, Oudemans G. The effect of praziquantel on Echinococcus granulosus, Taenia hydatigena and Taenia ovis infections in dogs. Res Vet Sci. 1977;23(1):121–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caffrey CR. Chemotherapy of schistosomiasis: present and future. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11(4):433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cioli D, Pica-Mattoccia L. Praziquantel. Parasitol Res. 2003;90(Suppl 1):S3–9. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0751-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cobo F, Yarnoz C, Sesma B, et al. Albendazole plus praziquantel versus albendazole alone as a pre-operative treatment in intra-abdominal hydatisosis caused by Echinococcus granulosus. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:462–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bale JF., Jr Cysticercosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2000;2:355–360. doi: 10.1007/s11940-000-0052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leopold G, Ungethüm W, Groll E, Diekmann HW, Nowak H, Wegner DHG. Clinical pharmacology in normal volunteers of praziquantel, a new drug against schistosomes and cestodes – an example of complex study covering both tolerance and pharmacokinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1978;14:281–291. doi: 10.1007/BF00560463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiao W, Cheng F, Qun Q, et al. Epidemiological evaluations of the efficacy of slow-released praziquantel-medicated bars for dogs in the prevention and control of cystic echinococcosis in man and animals. Parasitol Int. 2005;54(4):231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng L, Lei L, Guo SR. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of praziquantel loaded implants based on PEG/PCL blends. Int J Pharm. 2010;387(1–2):129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mourao SC, Costa PI, Salgado HR, Gremiao MP. Improvement of antischistosomal activity of praziquantel by incorporation into phosphatidylcholine- containing liposomes. Int J Pharm. 2005;295(1–2):157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hrcková G, Velebny S, Corba J. Effects of free and liposomized praziquantel on the surface morphology and motility of Mesocestoides vogae tetrathyridia (syn. M. corti; Cestoda: Cyclophyllidea) in vitro. Parasitol Res. 1998;84(3):230–238. doi: 10.1007/s004360050387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang L, Geng Y, Li H, Zhang Y, You J, Chang Y. Enhancement the oral bioavailability of praziquantel by incorporation into solid lipid nanoparticles. Pharmazie. 2009;64(2):86–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie S, Pan B, Wang M, et al. Formulation, characterization and pharmacokinetics of praziquantel-loaded hydrogenated castor oil solid lipid nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2010;5(5):693–701. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Müller RH, Mader K, Gohla W. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) for controlled drug delivery – a review of the state of the art. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50(1):161–177. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freitas C, Müller RH. Effect of light and temperature on zeta potential and physical stability in solid lipid nanoparticle (SLN™) dispersions. Int J Pharm. 1998;168(2):221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gulnur T, Mi XY, Zhang ZZ, et al. Using antibodies against tegument antigens for copro-ELISA to detect Echinococcus granulous in dogs. Acta Veterinaria et Zootechnica Sinica. 2011;42(6):845–850. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang WB, Li J, McManus DP. Concepts in immunology and diagnosis of hydatid disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16(1):18–36. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.18-36.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dryden MW, Payn PA, Ridley R, Smith V. Comparison of common fecal flotation techniques for the recovery of parasite eggs and oocysts. Vet Ther. 2005;6(1):15–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miró G, Mateo M, Montoya A, Vela E, Calonge R. Survey of intestinal parasites in stray dogs in the Madrid area and comparison of the efficacy of three anthelmintics in naturally infected dogs. Parasitol Res. 2007;100(2):317–320. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slocombe JO, Heine J, Barutzki D, Slacek B. Clinical trials of efficacy of praziquantel horse paste 9% against tapeworms and its safety in horses. Vet Parasitol. 2007;144(3–4):366–370. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong Z, Xie SY, Zhu LY, Wang Y, Wang XF, Zhou WZ. Preparation and in vitro, in vivo evaluations of norfloxacin-loaded solid lipid nanopartices for oral delivery. Drug Deliv. 2011;18(6):441–450. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2011.577109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papini R, Matteini A, Bandinelli P, Pampurini F, Mancianti F. Effectiveness of praziquantel for treatment of peritoneal larval cestodiasis in dogs: a case report. Vet Parasitol. 2010;170(1–2):158–161. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Müller RH, Radtke M, Wissing SA. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) in cosmetic and dermatological preparations. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2002;54(Suppl 1):S131–155. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schelling U, Frank W, Will R, Romig T, Lucius R. Chemotherapy with praziquantel has the potential to reduce the prevalence of Echinococcus multilocularis in wild foxes (Vulpes vulpes) Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91(2):179–186. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1997.11813128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eckert J, Deplazes P. Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(1):107–135. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.107-135.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang ZH, Wang XM, Liu XQ. Echinococcosis in China, a review of the epidemiology of Echinococcus spp. Eco Health. 2008;5:115–126. doi: 10.1007/s10393-008-0174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen FL, Conder GA, Marsland WP. Efficacy of injectable and tablet formulations of praziquantel against mature Echinococcus granulosus. Amer J Vet Res. 1978;39(11):1861–1862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andersen FL, Conder GA, Marsland WP. Efficacy of injectable and tablet formulations of praziquantel against immature Echinococcus granulosus. Amer J Vet Res. 1979;40(5):700–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]