Abstract

Cells are continuously sensing their physical and chemical environment, generating dynamic interactions with the surrounding micro-environment and cells. Specific to neurons, neurite outgrowth is influenced by many factors, including the growth substrata mechanical properties and adhesive signals. In designing biomaterials for neural regeneration, it is important to better understand the influence of substrate material, rigidity, and bioadhesion on neurite outgrowth. To this end, we developed and characterized a tunable 3-D methylcellulose (MC) hydrogel polymeric system tethered to laminin-1 (MC-x-LN) across a range of substrate rigidities (G* range = 50Pa to 565Pa) and laminin densities. Viability and neurite outgrowth of primary cortical neurons plated within 3-D MC hydrogels were used as cell outcome measures. After four days in culture, neuronal viability was significantly augmented with increasing rigidity for MC-x-LN as compared to control non-bioactive MC; however, neurite outgrowth was only observed in MC hydrogels with complex moduli of 565Pa. Varying LN while maintaining a constant MC formulation (G* = 565Pa) revealed a threshold response for neuronal viability, whereas a direct dose-dependent response to LN density was observed for neurite outgrowth. Collectively, these data demonstrate the synergistic play between material compliance and bioactive ligand concentrations within MC hydrogels. Such results can be used to better understand the adhesive and mechanical factors that mediate neuronal response to MC-based tissue engineered materials.

Keywords: hydrogel, 3-D neuronal culture, laminin, methylcellulose

1. Introduction

Multiple factors influence cellular adhesion and migration on natural or synthetic supports, including the physical properties and density of adhesive ligands. Non-fouling materials (e.g., polyethylene glycol, dexatran, methylcellulose hydrogels) provide a backbone to link specific biological motifs to control cellular adhesion, migration, and infiltration [1-4]. With many of these polymeric substrates, control over the substrate rigidity is possible through modifications of the polymeric matrix properties. Consequently, the relationship of matrix structure and substrate rigidity to cell adhesion, migration, and spreading has been studied in a variety of cellular systems [5-7]. Of particular interest are observations that cell behavior on similar materials varies based on cell type. For instance, fibroblasts spread and migrate on more rigid substrates [8, 9], whereas among neuronal phenotypes, more compliant substrates have been shown to support longer neurite outgrowth compared to more rigid materials [10-13]. In addition to material properties, specific combinations of ligand modality and density are essential for successful cell spreading, migration, and neurite outgrowth [6, 7, 14-16].

A number of in vitro neurite outgrowth studies have utilized polymeric hydrogel systems to assess neurite outgrowth in 3-D as the matrix structure and mechanical properties are unique to each specific material [1, 4, 10, 15]. Non-fouling polymers provide structural support while enabling covalent coupling of bioadhesive cues to generate designer 3-D scaffolds. Methylcellulose (MC) is one such non-fouling hydrogel system in which the mechanical properties can be tuned to a range of rigidities by modifying the solution concentration, ionic strength, and/or molecular weight. Moreover, the thermoresponsive property of MC is appealing for neural tissue engineering applications particularly for situations where the implanted material needs to conform to irregularly shaped lesions/defects (e.g. spinal cord and traumatic brain injuries) [17-20]. We previously reported successful functionalization of MC with the extracellular matrix protein (ECM) laminin-1 (LN) via two different conjugation schemes [1, 18]. Due to the ease of manipulating mechanical properties, biofunctionalization, and the potential for use in neural tissue engineering, we chose to evaluate neuronal response to alterations in mechanical and ECM tethering densities within MC hydrogels.

In vivo, cellular behavior is directed through numerous interactions a cell encounters with its external environment (i.e., cell-cell, ECM, growth factors, cytokines, etc). LN is of particular interest for neuronal behaviors as this 800kDa heterotrimeric protein stimulates cell-signaling pathways for adhesion, neuritogenesis, and survival (See Review [21]). Additionally, LN and LN-derived active moieties have been incorporated within polymeric matrices to study neurite outgrowth [10, 11, 22, 23]. However, questions still remain on how substrate material, rigidity and incorporation/density of bioactive moieties such as LN in a 3-D MC matrix may interact to affect neurite outgrowth.

In this study we evaluated neuronal response to variations in both MC matrix compliance and LN ligand density. Specifically, we focused on investigating the relationship between viscoelastic properties of MC and the tethering density of LN in relation to neuronal viability and neurite outgrowth. The knowledge gained from this study may be applied toward developing design criteria for MC-based neural tissue engineered constructs capable of eliciting and supporting neurite outgrowth.

2. Methods

2.1. Methylcellulose – Laminin Tethering Scheme

MC (methylcellulose, Mw~38k and 40kDa; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) hydrogels were prepared in Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (D-PBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to a dispersion technique previously reported [19]. Tethering of laminin-l (LN; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) to MC was accomplished via the photosensitive conjugation reagent N-sulfosuccinimidyl-6-[4′-azido-2′-nitrophenylamino] hexanoate (sulfo-SANPAH; Pierce Biotechnology, Inc, Rockford, IL). Briefly, LN (200 μg/mL; Invitrogen) was incubated with a 0.5 mg/mL sulfo-SANPAH solution in absence of light for 2.5 hours. Residual unreacted sulfo-SANPAH was removed with micro-centrifuge filters (NanoSep, 50000 MWCO; Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY). LN-SANPAH (200 μg/mL) was reconstituted and thoroughly mixed on ice with MC. A thin layer of the MC+LN-SANPAH mixture was then cast onto a glass slide and exposed to UV light for 4 minutes (100 W, 365 nm; BP-100AP lamp, UVP, Upland, CA) to initiate the photoconjugation reaction. Upon completion of the photoconjugation reaction, unbound LN rinsed away using D-PBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween-20 followed by three rinses with D-PBS. MC tethered to LN is referred to as MC-x-LN; unmodified MC is referred to as MC. For cell culture assays, we used MC tethered to bovine serum albumin (BSA, MC-x-BSA; Sigma) to control for any effects of the conjugation procedures. MC-x-BSA was generated according to MC-x-LN procedure, in which the molar equivalent amount of BSA was substituted for LN. Conjugation of LN to MC was quantified via a dot blot immunoassay [18].

2.2. Dynamic Rheological Characterization

Rheological analyses were performed on a Bohlin CVO rheometer (Bohlin, East Brunswick, NJ) with a parallel plate configuration (0.5mm thick and 12mm in diameter). To examine the mechanical integrity of the MC hydrogels at physiological temperatures, a frequency sweep from 0.05-5 Hz was performed on each sample group (n=6-8 per group) under constant low amplitude oscillatory shear strain (0.5%) upon equilibration to 37°C. We evaluated MC samples of varying polymer Mw (38kDa and 40kDa), MC concentration in DPBS (6.75%, 7.8%, and 9.0%), MC at various stages of the tethering scheme (UV irradiated MC and MC-x-BSA), and varied protein tethering densities (20 μg/mL, 200 μg/mL, and 400 μg/mL). The complex moduli over a 0.05 to 5 Hz frequency sweep were compared to determine differences in rigidity across groups.

2.3. Cortical Neuron Isolation and Dissociation

Cortices from embryonic day 18 (E18) Sasco Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were dissected and dissociated according to Georgia Institute of Technology Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocols. This well-established protocol was modified from the Brewer lab [24] and optimized for cortical neuron cultures. Briefly, cortices were extracted from E18 fetuses, rinsed twice with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS; Invitrogen), and placed in a hibernate solution consisting of L-15 supplemented with 2% B-27 (Invitrogen). Cortices were then stored at 4°C until dissociation and plating (maximum of 7 days post-dissection). Dissociation of the cortical tissue began with rinsing the tissue with cold HBSS thrice, followed by incubation in trypsin (0.25%) + EDTA (1 mM; Invitrogen) at 37°C for 10 minutes. Following removal of trypsin, cortices were rinsed twice with HBSS then placed in HBSS supplemented with DNase (0.15 mg/mL; Sigma) and vortexed for 30 seconds. Remaining tissue fragments were removed and the resulting cell suspension was centrifuged at 180g for 3 minutes. The cell pellet was resuspended in Neurobasal medium supplemented with 2% B-27 and 0.5 mM L-glutamine (neuronal medium; Invitrogen) and placed on ice until the cells were plated. Cells were plated within 30 minutes of dissociation with no reduction in viability, as measured with a standard trypan blue exclusion viability assay.

2.4. 3-D Neuronal Cultures within MC

Dissociated primary cortical neurons were mixed on ice with MC to achieve desired MC formulation and a plating density of 3.5 × 106 cells/mL. After thoroughly mixing the cell-MC solution, the solution was transferred into custom microwell chambers to attain a 300μm thick hydrogel (150μL volume). The plated cell-MC solution was allowed to gel at 37°C for 45 minutes in a tissue culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% relative humidity). Upon gelation, neuronal medium was added atop of the hydrogel. Experimental groups consisted of varying MC formulations and LN tethering densities (n = 4-7 trials in triplicate). Additional, control cultures were also plated on poly-L-lysine coated polystyrene to control for potential variations in viability between dissection/dissociation procedures. All cultures were maintained in a tissue culture incubator with neuronal medium exchanges every other day until the experimental endpoint.

2.5. Viability and Neurite Outgrowth

At 4 days post-plating, viability was assessed with calcein AM (Invitrogen) and ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1; Sigma). Briefly, cultures were rinsed with PBS and then incubated with PBS containing 2 μM calcein AM and 4 μM EthD-1 for 30 minutes. Upon removal of the calcein AM/EthD-1 solution and subsequent rinsing, cellular viability was examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 510; Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Three random 100 μm thick z-stacks for each construct were captured and analyzed with LSM Image Browser (Zeiss) to record viability and neurite outgrowth. Each confocal z-stack was projected into a 2-D image to facilitate cell counting for cell viability quantification; the total number of calcein AM cells were divided by the total number of calcein AM and EthD-1 cells. The cell density within each 3-D culture was calculated from total cell count data (i.e., calcein AM + EthD-1 cells) divided by the confocal z-stack volume. Viability data were normalized to MC-x-BSA controls. From each 2-D projection, we also recorded the percentage of viable neurons that extended neurites of 20 μm or greater.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as ± one standard deviation from the mean. Results were analyzed by the appropriate one- or multi-way ANOVA, followed by pair-wise comparisons with Tukey’s or Bonferroni post-hoc test (Prism 5, GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). A 95% confidence level and corresponding p value <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Bioactive MC: LN Tethered to MC

LN was tethered to MC via the heterobifunctional crosslinker sulfo-SANPAH [18]. The reactions of this tethering scheme occur at physiological pH without harsh organic solvents, one of the advantages of sulfo-SANPAH. The NHS esters react efficiently with primary amino groups (-NH2) in the protein at pH 7-9 buffers to form stable amide bonds. This compound was then mixed with MC and exposed to UV light initiating the nitrophenyl azide end group to form a nitrene group which inserts into the C-H bonds in MC. We previously reported the conjugation efficiency as 4.1% with an initial LN reaction concentration of with 200 μg/mL LN, thus yielding 8.2 ± 1.3 μg LN per mL of MC [18]. Dodla et. al demonstrated increasing tethering density relative to increasing concentrations of LN present during the tethering reaction with sulfo-SANPAH and the conjugation efficiency was similar for LN concentrations above 100 μg/mL [22]. Therefore, based on these previous we generated a range of LN densities by varying the LN concentration during the tethering reaction (0, 20, 200, and 400 μg/mL). Assuming uniform conjugation efficiency, the LN density ranged from 0, 0.82, 8.2, and 16.4 μg of LN per mL of MC.

3.2. Rheological Properties of MC Hydrogels

3.2.1. Rigidity range obtained by varying MC Mw and concentration

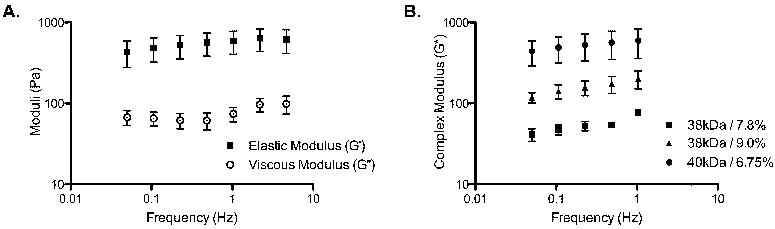

The viscoelasticity of the MC hydrogels was evaluated by rheology. MC formulations varied in molecular weight (Mw) and concentration (%w/v) in D-PBS. For all MC formulations, the elastic moduli (G’) dominated the viscous moduli (G”), indicating that at physiologically relevant temperatures (i.e., 37°C) MC was in a gelled state (Figure 1A). Comparing the complex moduli (G*) revealed significant rigidity differences among the MC groups (Figure 1B and Table 1; p <0.01, F(2, 55) = 127.0 for MC formulation, 2-way ANOVA). Increasing the concentration of MC (38kDa) from 7.8% to 9.0% resulted in a greater than threefold more rigid gel (G* = 50Pa to 175Pa at 0.5Hz; p<0.05). However, by increasing Mw chain from 38kDa to 40kDa, a more prominent 10-fold increase in G* was observed (~50Pa to 565Pa at 0.5Hz; p < 0.001). Looking at the contributions from the elastic and viscous components for all MC formulations, it was apparent that elastic moduli largely dominated the complex moduli (Table 1). It should be noted that the 40kDa MC solution at a matching concentration of 7.8% was extremely viscous and difficult to pipette; therefore the concentration was decreased to a manageable 6.75% for this study.

Figure 1.

Viscoelastic Properties. A. Representative plot of rheological data from MC 40kDa / 6.75% demonstrates that the elastic (G’, ■) modulus dominates the viscous modulus (G”, ○) indicating a gelled state at 37°C. This trend was observed for all MC formulations. B. Comparison of the complex modulus (G*) for each MC formulation established a difference in substrate rigidity that was dependent on molecular weight and concentration (w/v) in 1X D-PBS. Data presented as mean ± SEM.

Table 1.

Viscoelastic properties of MC forumulations. Average Complex, Elastic, and Viscous moduli at 0.5Hz for each MC formulation. One-way ANOVA revealed significant differences among groups (F = 182.7). Tukey’s post-hoc analysis revealed significant differences in pairwise comparisons between all groups (p < 0.05).

| MC Formulation | Complex Modulus (G* at 0.5Hz) | Elastic Modulus (G’ at 0.5Hz) | Viscous Modulus (G” at 0.5Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 38kDa / 7.8% | 53 ± 8 Pa | 53 ± 4 Pa | 8 ± 2 Pa |

| 38kDa / 9.0% | 174 ± 32 Pa | 171 ± 41 Pa | 26 ± 6 Pa |

| 40kDa / 6.75% | 565 ± 102 Pa | 560 ± 166 Pa | 61 ± 29 Pa |

3.2.2. Biofunctionalization did not significantly alter hydrogel viscoelasticity

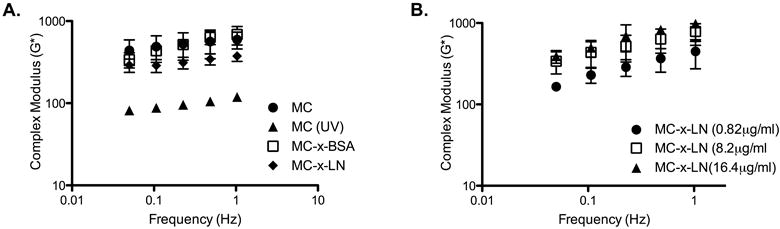

The tethering scheme includes a UV photo-initiated crosslinker to tether LN to MC. Therefore, we measured the viscoelasticity throughout the tethering scheme to ensure the properties of the end product (MC-x-LN) were not substantially affected by the tethering scheme as it has been previously reported degradation of the MC polymer chain under UV irradiation [25, 26]. Native MC, UV irradiated MC, MC-x-BSA, and MC-x-LN groups tested were of the same Mw, concentration, and protein tethering densities (40kDa, 6.75% in 1X DPBS, and 8.2 μg/mL BSA or LN; Figure 2A). We determined that UV irradiation to MC alone significantly decreased the complex modulus from 565Pa to 100Pa (Figure 2A; p < 0.01, F(3, 55) = 59.76 for MC group variation, 2-way ANOVA). However, completion of the protein tethering process with either LN-SANPAH or BSA-SANPAH did not significantly alter the complex moduli from the original range of native MC (Figure 2A; p > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Viscoelasticity is not significantly altered after photoconjugation scheme. A. Complex modulus (G*) of MC, UV exposed MC, MC-x-BSA, and MC-x-LN (Mw 40kDa at 6.75% in 1X DPBS). B. Varying the LN tethering densities did not significantly influence the complex modulus of MC-x-LN.

We also measured the rheological properties of the MC-x-LN groups with varying LN tethering densities to determine if LN tethering densities affect the viscoelastic properties of the resulting conjugate (40kDa MC at 6.75% in 1X DPBS with 0.82 μg/mL, 8.2 μg/mL, 16.4 μg/mL; Figure 2B). Within the range of LN densities we evaluated, the complex modulus of the tethered MC-LN products was not significantly dependent on LN density (Figure 2B) (p < 0.998, F(3, 60) = 0.2 for LN density variation, 2-way ANOVA). Collectively, the results demonstrated that MC-x-LN hydrogels with varying LN densities were generated without affecting the bulk mechanical integrity of the hydrogel.

3.3. 3-D Neuronal Cultures in MC-x-LN

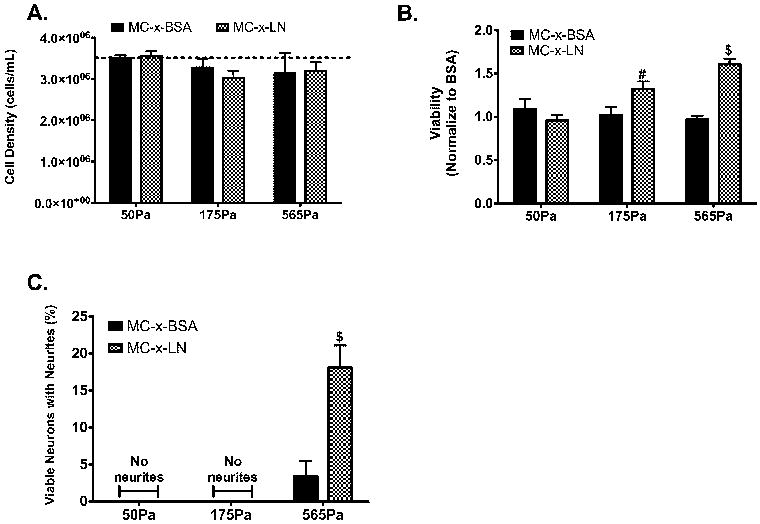

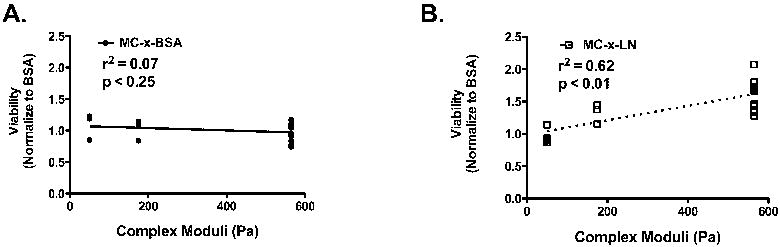

3.3.1. Viability and neurite outgrowth dependent on mechanical properties

The effect of the MC rigidity on 3-D neuronal culture viability and neurite outgrowth were investigated with the three varied hydrogel rigidities (G* = 50Pa, 175Pa, and 565Pa). MC tethered to BSA (MC-x-BSA) served as the baseline control for viability in a non-bioactive MC hydrogel. Matching MC formulations tethered to LN (tethered concentration of 8.2 μg/mL; MC-x-LN) were used to evaluate bioactive MC hydrogels at varying mechanical strengths. To highlight differences in viability among the experimental groups, viability data was normalized to the mean viability observed in MC-x-BSA controls across all three rigidity formulations. At 4 days post-plating in vitro, total cell density did not signifanctly deviate among groups nor the initial plating density (Figure 3A). The viability of the neurons plated in the MC-x-BSA gels did not significantly differ among the three different rigidities (Figure 3B). Additionally, the viability for the softest gel (50Pa) did not significantly deviate from baseline control level when tethered to LN (Figure 3B). Conversely, in the 175Pa formulation with LN, the viability significantly increased nearly 20% of the MC-x-BSA control (p < 0.05). Most strikingly, the presence of LN in the 565Pa MC formulation significantly increased nearly 60% compared to the MC-x-BSA control (p <0.01). Linear regression analysis on viability relative mechanical properties enabled further analysis of the relationship between MC rigidity and viability (Figure 4). The slope of the linear fit for MC-x-BSA viability was not significantly non-zero (r2 = 0.08, p < 0.25; Figure 4A), indicating the the mechanical properties had no effect on viability in the non-active MC-x-BSA cultures. In contrast, the positive slope for the linear regression of the MC-x-LN data was significantly non-zero (r2 = 0.62, p < 0.001; Figure 4B), indicating a direct relationship between the mechanical integrity of MC-x-LN hydrogels when the bioadhesive molecule LN is present.

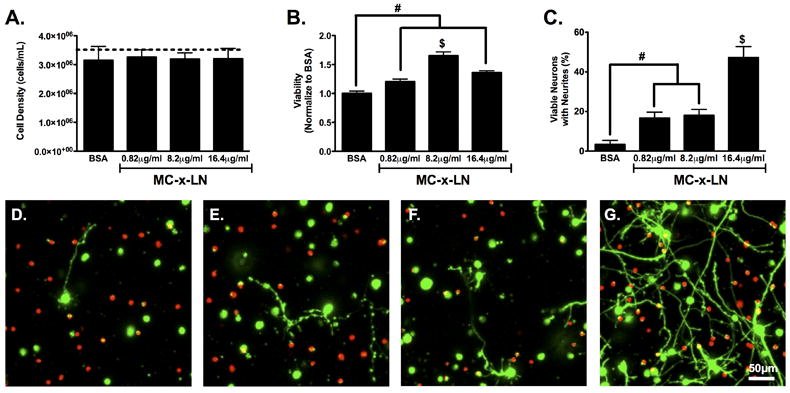

Figure 3.

Neuronal viability and neurite outgrowth dependent on MC mechanical properties. A. Cell density of cell cultures at 4 days post-plating in MC of three varying rigidities with and without LN. Dashed line represents initial plating density. B. Cellular viability as measured with calcein AM and EthD-1 stain normalized to average MC-x-BSA. C. Quantification of the percentage of viable neurons extending neurite processes. (n = 4-7, mean ± SEM, # represents p ≤ 0.05, $ represents p ≤ 0.001 relative to all groups)

Figure 4.

Viability directly related increasing MC-x-LN rigidity. A. Linear regression analysis of normalized viability responses within MC-x-BSA at varying rigidities. B. Linear regression analysis of normalized viability responses within MC-x-LN at varying rigidities.

Evaluation of neurite outgrowth further revealed differences in neuronal response among MC formulations (Figure 3C). Neurite outgrowth was absent in the lower moduli gels (50Pa and 175Pa) regardless of whether or not MC was tethered to LN. In contrast, we observed a low level of neurite outgrowth within the stiffest MC-x-BSA formulation (565Pa). An additional 5-fold increase was observed within 565Pa MC-x-LN compared to MC-x-BSA (p <0.01, Figure 3C). Based on these positive observations, we used the 565Pa MC formulations for the remainder of the studies to evaluate the influence of LN density on viability and neurite outgrowth.

3.3.2. Viability and neurite outgrowth dependent on tethered LN concentration

To evaluate the effect of varied LN densities on neuronal viability and neurite outgrowth, the MC formulation was held constant (565Pa) while a range of tethered LN concentrations was examined (n=4-8 per group; tethered concentration = 0.82, 8.2, or 16.2 μg/mL). MC-x-BSA served as the negative control to examine the specificity of LN. Similar to the results above, the cell density at 4 days post plating was not significantly different among groups nor the initial plating density (Figure 5A). Viability data were normalized to MC-x-BSA to evaluate viability in relation to the baseline non-bioactive MC hydrogel. The viability in MC-x-LN with lowest LN concentration (0.82 μg/mL) significantly increased compared to MC-x-BSA (p < 0.05, Figure 5B). Increasing the LN concentration to 8.2 μg/mL further enhanced viability to nearly 60% of the control (p < 0.01). However, doubling the LN concentration to 16.4 μg/mL did not provide any significant benefit to the viability. These results indicate that the LN density positively influenced neuronal viability until reaching a plateau at 8.2 μg/mL.

Figure 5.

Tethered LN enhanced viability and neurite outgrowth. A. Cell density of cell cultures at 4 days post-plating. Dashed line represents initial plating density. B. Cellular viability as measured with calcein AM and EthD-1 stain. C. Quantification of the percentage of viable neurons extending neurite processes. (n = 4-7, mean ± SEM, # represents p ≤ 0.05, $ represents p ≤ 0.01 relative to all groups). D-G. Confocal micrograph projections of 100 μm z-stacks, D. MC-x-BSA, E. MC-x-LN 0.82 μg/mL, F. MC-x-LN 8.2 μg/mL, and G. MC-x-LN 16.4 μg/mL.

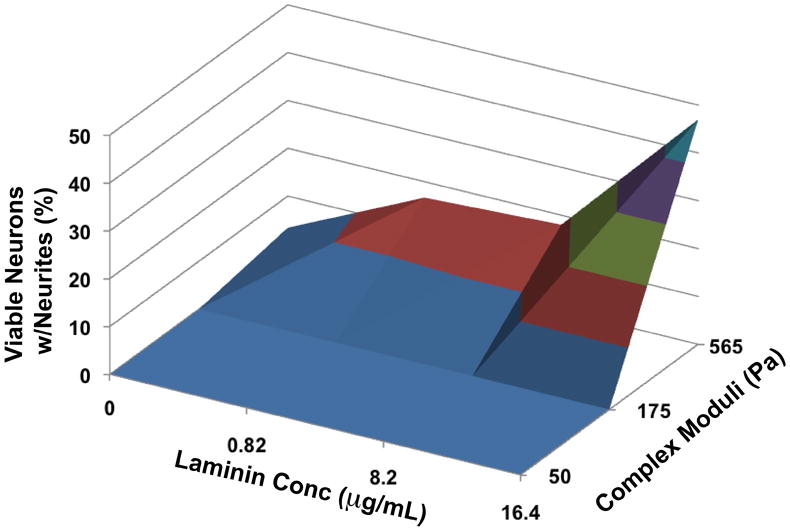

For neurite extension, the percentage of live cells with one or more neurite extensions significantly increased in all MC-x-LN groups compared to MC-x-BSA (p < 0.01, Figure 5C). Specifically, neurons cultured within the 0.82 and 8.2 μg/mL MC-x-LN gels extended 5-fold more neurites compare to the MC-x-BSA control (p < 0.01); however, no significant difference was observed between 0.82 and 8.2 μg/mL MC-x-LN formulations. Most strikingly, the 16.4 μg/mL MC-x-LN gels supported the highest percentage of neurite extensions, nearly 3-fold greater than 0.82 and 8.2 μg/mL and 15-fold greater than control MC-x-BSA (p < 0.001). Therefore, for this study, we observed a critical threshold of LN ligand (≥ 8.2 μg/mL) for maximum viability under these conditions, whereas the lowest concentration of LN (≥ 0.82 μg/mL) significantly enhanced neurite outgrowth compared to MC-x-BSA and increased in a dose-dependent manner. Graphically representing the neurite outgrowth data in a 3-D surface plot clearly demonstrates the collective influence of both MC compliance and LN concentration on neurite outgrowth (Figure 6), where concomitant increase in stiffness and LN concentration yielded the highest levels of neurite outgrowth.

Figure 6.

Neurite outgrowth dependent on rigidity and LN concentration. 3-D surface plot of neurite outgrowth with respect to laminin concentration and complex moduli of MC.

4. Discussion

Three main parameters influence initial neuronal attachment and subsequent neurite outgrowth in vitro, namely substrate material, rigidity, and ligand density [4, 10-15]; yet, the interplay or correlation between these parameters is not well understood, particularly for cells within 3-D hydrogel systems. In this study, the substrate material was held constant while we varied the rigidity and ligand density. The results demonstrate that cortical neuron viability and neurite outgrowth in 3-D MC hydrogels were dependent on substrate rigidity and LN density.

To accurately evaluate cell behavior in vitro, matching of cell culture substrate and in vivo mechanical properties may be a critical parameter [11, 27]. A review presented by Georges and Janmey highlighted the correlation between optimal mechanical properties for plating substrates and the measured mechanical properties of corresponding tissue [28]. Mechanical matching to specific tissue type is not only critical for in vitro cell studies, but it is also important for future tissue engineering considerations to ensure minimal mechanical mismatch at the host-implant interface. In our study, the MC formulations were intentionally tuned to span the dynamic mechanical range reported for cortical tissue (G’ = 150 – 500 Pa depending on the anatomical region, species, and age) [29-32]. This dynamic range was achieved by increasing either the concentration (7.8% to 9.0% of 38kDa MC) or the molecular weight (38kDa to 40kDa). What appear to be relatively small incremental changes in each parameter resulted in significant alterations in the viscoelastic properties. For example, the 40kDa MC contains approximately 3,000 more monomers per polymer chain compared to the 38kDa MC. Since MC forms physical, non-covalent crosslinks via intra- and inter-hydrophobic interactions, the increased number of hydrophobic monomers in the 40kDa MC formulation enhanced the propensity of hydrophobic interactions to generate a significantly more rigid hydrogel. We were also concerned that covalently tethering LN to MC directly to the MC chain would disrupt critical hydrophobic interactions required for gelation. However, we demonstrated that fully completing the photoconjugation scheme did not alter the mechanical properties. In contrast, exposing native MC to UV irradiation alone resulted in a significant decrease in complex modulus. Previous studies have reported degradation via scission of MC after UV irradiation [25, 26]. We speculate that UV exposure to native MC potentially degraded the polymer chains leading to the decreased mechanical integrity. We further speculate that the presence of the photoreactive SANPAH in the photoconjugation scheme consumed the majority of the irradiation energy to convert nitrophenyl azide groups to nitrene groups thus minimizing damage to MC polymer chain.

Traditionally, neurite outgrowth is considered to be inversely proportional to substrate rigidity [10-12]. However recent studies have challenged this notion, as neurite outgrowth on or within a specific material has been shown to exhibit a threshold and/or biphasic response over a range of mechanical properties [14, 15]. Specifically, a mechanical threshold for neurite outgrowth was observed with PC-12 cells plated in 2-D on a polymeric substrate with constant ligand density, but altered stiffness [14]. Such observations and reports are not surprising since similar biphasic responses have been reported for cell spreading and migration of fibroblasts, endothelial cells, hepatocytes, and myocytes [8, 9, 27]. In this study, we also observed a mechanical threshold for neurite outgrowth as neurite outgrowth. Rather than an inverse relationship between mechanical stiffness and neurite outgrowth, we convincingly show that softer MC-x-LN formulations did not support neurite outgrowth (50Pa and 175Pa), yet the stiffer 565Pa supported significantly more neurite extension (Figure 6). One Collectively, our results indicate that mechanical properties of a MC hydrogel play a significant role in determining neuronal cell behavior.

ECM proteins collagen IV, LN, and fibronectin have been shown to affect neurite outgrowth in a ligand concentration dependent manner [4, 14, 15]. In this study, we observed a direct positive correlation between LN tethering density and neurite outgrowth from primary cortical neurons. A multitude of studies indicate that neurite outgrowth correlates not only to isotropic ligand concentrations, but also anisotropic gradients for directed neurite outgrowth [4, 15, 16, 22, 23, 33-35]. However, similar to mechanical parameters, a biphasic cellular migration response to ligand density has been reported [36, 37]. At low protein densities, limited ligand availability inhibits cellular attachment and the ability to generate traction required for cellular motility. At high ligand densities, an over abundant amount of cell-ECM interactions actually hinders forward propulsion of the cell due to receptor saturation [37, 38]. In this study, we demonstrated that tethering LN to MC significantly enhanced neurite outgrowth in MC hydrogels. The percentage of neurons with neurites directly correlated with the density of LN present in the hydrogel (Figure 4), thus indicating that LN density within the MC-x-LN hydrogel did not surpass a peak in which neurite outgrowth would be hindered.

Additional complexities arise in attempting to generalize material properties for neurite outgrowth including substrate dimensionality (i.e. 2-D versus 3-D). The cellular microenvironment for a 2-D and 3-D experiment differs immensely. In 2-D however, cell-ECM interactions are limited to the cell-material interface. In contrast, in a 3-D configuration, cells are embedded in the matrix and can engage ECM-cell interactions on all surfaces of its membrane. For 3-D matrices, the substrate tortuosity and pore size must provide large enough voids to allow cell migration/axonal growth and/or enzymatic cleavable sites for cells to actively degrade the matrix as they migrate. Our lab previously reported the pore size of 38kDa MC at 8% to be relatively homogenous at 30-50 μm as measured by SEM [19], consistent with the pore size of the 565Pa MC-x-LN formulation in this study (20-40 μm as measured with SEM) further establishing MC as a growth-promoting matrix with geometry conducive to cellular migration and neurite outgrowth.

5. Conclusion

This study evaluated the effects of MC hydrogel formulation (polymer chain length and concentration) and protein tethering density on primary cortical neuron viability and neurite outgrowth. The results indicate that neuronal viability in MC-x-BSA groups was similar regardless of MC compliance, while a significant increase in viability was observed with the addition of LN only in the 175Pa and 565Pa MC formulations but not the 50Pa formulation. However, neurite outgrowth was only observed within the stiffest 565Pa MC group, which significantly monotonically increased with increasing LN density. Ultimately, understanding the key parameters that influence neural cellular response to specific biomaterials is critical for developing neural regenerative therapeutic strategies. Thermosensitive materials such as MC are attractive for neural tissue engineering, as the material may be injected as a liquid and conform to an irregularly shaped lesion or gap [17, 19]. Our study demonstrated that both the mechanical properties and bioadhesive ligand density are critical design aspects to consider for future MC-based cell and tissue engineering studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH NRSA Fellowship (F31 NS054527; SES), NSF EEC- 9731643 (MCL), and NIH EB001014 (MCL). We thank the following people for their technical assistance: A.J. García, R. Bellamkonda, M. Dodla, M. Levenston, and C. Wilson. We acknowledge R. Riebesell, J. Kroger, and G. Munglani for assisting with image quantification and rheology analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Stabenfeldt SE, Garcia AJ, LaPlaca MC. Thermoreversible laminin-functionalized hydrogel for neural tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2006;77A:718–25. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hern DL, Hubbell JA. Incorporation of adhesion peptides into nonadhesive hydrogels useful for tissue resurfacing. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1998;39:266–76. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199802)39:2<266::aid-jbm14>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahoney MJ, Anseth KS. Three-dimensional growth and function of neural tissue in degradable polyethylene glycol hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2265–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellamkonda R, Ranieri JP, Aebischer P. Laminin Oligopeptide Derivatized Agarose Gels Allow 3- Dimensional Neurite Extension in-Vitro. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1995;41:501–9. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490410409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray DS, Tien J, Chen CS. Repositioning of cells by mechanotaxis on surfaces with micropatterned Young’s modulus. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;66:605–14. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang G, Huang AH, Cai Y, Tanase M, Sheetz MP. Rigidity sensing at the leading edge through alphavbeta3 integrins and RPTPalpha. Biophys J. 2006;90:1804–9. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.072462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeung T, Georges PC, Flanagan LA, Marg B, Ortiz M, Funaki M, et al. Effects of substrate stiffness on cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure, and adhesion. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2005;60:24–34. doi: 10.1002/cm.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo WH, Frey MT, Burnham NA, Wang YL. Substrate rigidity regulates the formation and maintenance of tissues. Biophys J. 2006;90:2213–20. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.070144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelham RJ, Jr, Wang Y. Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13661–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balgude AP, Yu X, Szymanski A, Bellamkonda RV. Agarose gel stiffness determines rate of DRG neurite extension in 3D cultures. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1077–84. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Georges PC, Miller WJ, Meaney DF, Sawyer ES, Janmey PA. Matrices with compliance comparable to that of brain tissue select neuronal over glial growth in mixed cortical cultures. Biophys J. 2006;90:3012–8. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.073114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willits RK, Skornia SL. Effect of collagen gel stiffness on neurite extension. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2004;15:1521–31. doi: 10.1163/1568562042459698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flanagan LA, Ju YE, Marg B, Osterfield M, Janmey PA. Neurite branching on deformable substrates. NeuroReport. 2002;13:2411–5. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000048003.96487.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leach JB, Brown XQ, Jacot JG, Dimilla PA, Wong JY. Neurite outgrowth and branching of PC12 cells on very soft substrates sharply decreases below a threshold of substrate rigidity. Journal of neural engineering. 2007;4:26–34. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/4/2/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cullen DK, Lessing MC, LaPlaca MC. Collagen-dependent neurite outgrowth and response to dynamic deformation in three-dimensional neuronal cultures. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2007;35:835–46. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9292-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connor SM, Stenger DA, Shaffer KM, Ma W. Survival and neurite outgrowth of rat cortical neurons in three-dimensional agarose and collagen gel matrices. Neuroscience Letters. 2001;304:189–93. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01769-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin BC, Minner EJ, Wiseman SL, Klank RL, Gilbert RJ. Agarose and methylcellulose hydrogel blends for nerve regeneration applications. Journal of neural engineering. 2008;5:221–31. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/5/2/013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stabenfeldt SE, Munglani G, Garcia AJ, LaPlaca MC. Biomimetic Microenvironment Modulates Neural Stem Cell Survival, Migration, and Differentiation. Tissue Eng Pt A. 2010;16:3747–58. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tate MC, Shear DA, Hoffman SW, Stein DG, LaPlaca MC. Biocompatibility of methylcellulose-based constructs designed for intracerebral gelation following experimental traumatic brain injury. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1113–23. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai EC, Dalton PD, Shoichet MS, Tator CH. Matrix inclusion within synthetic hydrogel guidance channels improves specific supraspinal and local axonal regeneration after complete spinal cord transection. Biomaterials. 2006;27:519–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell SK, Kleinman HK. Neuronal laminins and their cellular receptors. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 1997;29:401–14. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dodla MC, Bellamkonda RV. Anisotropic scaffolds facilitate enhanced neurite extension in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;78:213–21. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu XJ, Dillon GP, Bellamkonda RV. A laminin and nerve growth factor-laden three-dimensional scaffold for enhanced neurite extension. Tissue Engineering. 1999;5:291–304. doi: 10.1089/ten.1999.5.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brewer GJ. Isolation and culture of adult rat hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1997;71:143–55. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(96)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wach RA, Mitomo H, Yoshii F. ESR investigation on gamma-irradiated methylcellulose and hydroxyethylcellulose in dry state and in aqueous solution. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry. 2004;261:113–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrov P, Petrova E, Stamenova R, Tsvetanov CB, Riess G. Cryogels of cellulose derivatives prepared via UV irradiation of moderately frozen systems. Polymer. 2006;47:6481–4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engler AJ, Griffin MA, Sen S, Bonnemann CG, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Myotubes differentiate optimally on substrates with tissue-like stiffness: pathological implications for soft or stiff microenvironments. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:877–87. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Georges PC, Janmey PA. Cell type-specific response to growth on soft materials. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1547–53. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01121.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coats B, Margulies SS. Material properties of porcine parietal cortex. Journal of biomechanics. 2006;39:2521–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gefen A, Margulies SS. Are in vivo and in situ brain tissues mechanically similar? Journal of biomechanics. 2004;37:1339–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prange MT, Margulies SS. Regional, directional, and age-dependent properties of the brain undergoing large deformation. J Biomech Eng. 2002;124:244–52. doi: 10.1115/1.1449907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thibault KL, Margulies SS. Age-dependent material properties of the porcine cerebrum: effect on pediatric inertial head injury criteria. Journal of biomechanics. 1998;31:1119–26. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kapur TA, Shoichet MS. Immobilized concentration gradients of nerve growth factor guide neurite outgrowth. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2004;68A:235–43. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pittier R, Sauthier F, Hubbell JA, Hall H. Neurite extension and in vitro myelination within three-dimensional modified fibrin matrices. Journal of Neurobiology. 2005;63:1–14. doi: 10.1002/neu.20116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sakiyama-Elbert SE, Hubbell JA. Controlled release of nerve growth factor from a heparin-containing fibrin-based cell ingrowth matrix. Journal of Controlled Release. 2000;69:149–58. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engler A, Bacakova L, Newman C, Hategan A, Griffin M, Discher D. Substrate compliance versus ligand density in cell on gel responses. Biophys J. 2004;86:617–28. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu P, Hoying JB, Williams SK, Kozikowski BA, Lauffenburger DA. Integrin-binding peptide in solution inhibits or enhances endothelial cell migration, predictably from cell adhesion. Annals of biomedical engineering. 1994;22:144–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02390372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DiMilla PA, Barbee K, Lauffenburger DA. Mathematical model for the effects of adhesion and mechanics on cell migration speed. Biophys J. 1991;60:15–37. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82027-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]