A substantial proportion of patients treated for early syphilis have serofast nontreponemal titers after therapy. Serological cure at 6 months is associated with age, number of sexual partners, Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, and an interaction between syphilis stage and baseline nontreponemal titers.

Abstract

Background. Syphilis management requires serological monitoring after therapy. We compared factors associated with serological response after treatment of early (ie, primary, secondary, or early latent) syphilis.

Methods. We performed secondary analyses of data from a prospective, randomized syphilis trial conducted in the United States and Madagascar. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–negative participants aged ≥18 years with early syphilis were enrolled from 2000–2009. Serological testing was performed at baseline and at 3 and 6 months after treatment. At 6 months, serological cure was defined as a negative rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test or a ≥4-fold decreased titer, and serofast status was defined as a ≤2-fold decreased titer or persistent titers that did not meet criteria for treatment failure.

Results. Data were available from 465 participants, of whom 369 (79%) achieved serological cure and 96 (21%) were serofast. In bivariate analysis, serological cure was associated with younger age, fewer sex partners, higher baseline RPR titers, and earlier syphilis stage (P ≤ .008). There was a less significant association with Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after treatment (P = .08). Multivariate analysis revealed interactions between log-transformed baseline titer with syphilis stage, in which the likelihood of cure was associated with increased titers among participants with primary syphilis (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] for 1 unit change in log2 titer, 1.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.25–2.70), secondary syphilis (AOR, 3.15; 95% CI, 2.14–4.65), and early latent syphilis (AOR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.44–2.40).

Conclusions. Serological cure at 6 months after early syphilis treatment is associated with age, number of sex partners, Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, and an interaction between syphilis stage and baseline RPR titer.

During the past century, medications for syphilis have evolved from mercury-based compounds to penicillin, which has been the therapy of choice for >60 years [1]. Although syphilis treatment recommendations have advanced since the prepenicillin era, the basis for evaluating therapeutic response remains serological testing. Clinical management relies upon interpretation of nontreponemal antibody test titers to assess treatment response, despite their inherent flaws including false-positive results and day-to-day variation in performance between assays.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends obtaining nontreponemal test titers to evaluate serological response at 6 and 12 months after treatment for primary and secondary syphilis and, additionally, at 24 months for early latent (EL) syphilis among persons without human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection [2]. Patients with nontreponemal titers that decline 4-fold or more are regarded as having an appropriate serological response, whereas those with a ≥4-fold increase are considered as having possible treatment failure or reinfection [2]. However, in a substantial proportion (15%–20%) of persons with early syphilis, nontreponemal titers neither increase nor decrease 4-fold after treatment and are referred to as being “serofast” [2–5]. The factors that predict serological response after syphilis treatment have not been well-defined, and the optimal management of serofast patients is unclear.

We conducted a large, randomized, multicenter study to compare the efficacy of benzathine penicillin with azithromycin for the treatment of early syphilis (defined as primary, secondary, or EL syphilis) in persons without HIV infection [4]. We found that both drugs had comparable efficacy with similar serological cure rates at 6 months, supporting other studies evaluating azithromycin as a potential therapy for Treponema pallidum infections [5, 6]. To begin to address the conundrum of serofast status, we examined the data collected from this study and assessed baseline factors associated with serological response.

METHODS

Study Design and Intervention

The open-label, randomized controlled trial was conducted from 12 June 2000 to 6 March 2009 at 5 sexually transmitted disease clinics in North America and 3 clinics in Madagascar [4]. The master protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and study sites.

Eligibility criteria and study procedures were described by Hook et al [4]. All participants were required to have reactive syphilis serological tests. In addition, primary syphilis was defined by the presence of genital ulcers positive for T. pallidum by dark-field examination or direct fluorescence antibody testing; secondary syphilis, by a palmar/plantar rash, condylomata lata, or lesions positive for T. pallidum by dark-field examination or direct fluorescence antibody testing; and EL syphilis, by documented seroconversion from a nonreactive serological result or sexual exposure in the past 12 months to a patient with known early syphilis [7]. Non–penicillin-allergic participants underwent treatment randomization to receive benzathine penicillin (2.4 million U by intramuscular injection) or azithromycin (2.0 g taken orally) as directly observed therapy [4]. Penicillin-allergic participants were randomized to receive doxycycline (100 mg taken orally twice daily for 14 days) or the azithromycin regimen. At baseline and at 3 and 6 months after treatment, participants had rapid plasma reagin (RPR) testing performed at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, according to published standards [7].

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was response to therapy, determined on the basis of changes in RPR titers at 6 months after treatment. Serological cure was defined as either negative RPR test results or a ≥4-fold (2 dilution) decrease in titer at 6 months. Serofast status was defined as either no change in titer or a ≤2-fold (1 dilution) titer decrease or increase from baseline [2]. All participants who had serofast status or did not respond to treatment at 6 months (defined as ≥4-fold titer increase without a clear history of reexposure) were retreated with benzathine penicillin or doxycycline.

Data Analysis

We performed statistical analyses on a subset of the original per-protocol cohort, which included participants without a change in protocol status (ie, pregnancy or HIV infection after enrollment) before the 6-month visit, [4] and who had serological data at 6 months after treatment. The proportion of participants with serological cure, serofast status, and treatment failure at 6 months in each treatment arm was determined. After exclusion of participants with serological treatment failure, we compared participants with serological cure to those with serofast status and conducted bivariate analyses with SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute) to determine associations with cure, using demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics (ie, history syphilis, underlying medical conditions, syphilis stage, baseline RPR titer, Jarisch-Herxheimer [J-H] reaction, initial treatment regimen), and behavioral characteristics (ie, sexual orientation and number of sex partners in past 6 months) that were chosen a priori on the basis of hypotheses of factors that may affect therapeutic response. Signs of syphilis were not included in the analyses, because they define syphilis stage. We estimated odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from the bivariate analysis, and factors with P values of <.20 were examined in multivariate analysis. Model development was conducted with the inclusion of all selected variables and their pair-wise interactions, using a step-down approach. A step-up approach was also implemented to avoid inappropriate automatic elimination or inclusion of model terms. Adjusted prevalence odds ratios (AORs) were estimated with 95% CIs from the regression procedure, to determine associations with serological cure at 6 months after therapy.

RESULTS

Participants and Response to Therapy

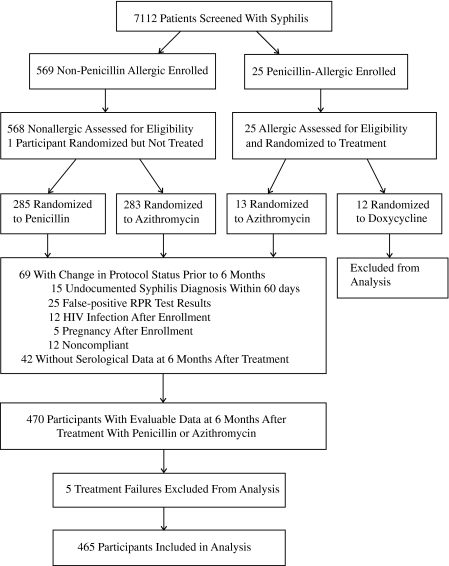

From June 2000 to March 2009, we screened 7112 patients and enrolled 593 (Figure 1). Among 568 non–penicillin-allergic participants, 285 received benzathine penicillin, and 283 received azithromycin. Of the 25 participants who were allergic to penicillin, 12 received doxycycline, and 13 received azithromycin. At 6 months after therapy, most participants exhibited serological cure regardless of treatment regimen, but ∼20% were serofast (Table 1). There were 4 treatment failures in the azithromycin group among Malagasy participants (whose titers increased by >2 dilutions); these were unlikely to have been due to azithromycin resistance in the absence of azithromycin detection in T. pallidum isolates from Madagascar [8]. Because there were no significant differences in the proportions of participants with serological cure or serofast status between treatment arms, the rest of the analysis was conducted using combined data from participants who received either penicillin or azithromycin. The small number of participants who experienced treatment failure or received doxycycline were excluded from further analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants in the trial and inclusion in the secondary analysis.

Table 1.

Comparison of Response to Therapy Between Treatment Arms, Determined 6 Months After Treatment

| Response type | Treatment arm, no. (%) of participants |

||||

| Not allergic to penicillin |

Allergic to penicillin |

Total | |||

| Benzathine penicillin | Azithromycin | Doxycycline | Azithromycin | ||

| (n = 231) | (n = 226) | (n = 9) | (n = 13) | (n = 479) | |

| Serological cure | 182 (78.8) | 177 (78.3) | 7 (77.8) | 10 (76.9) | 376 (78.5) |

| Serofast | 48 (20.8) | 46 (20.4) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (15.4) | 98 (20.5) |

| Treatment failure | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.3) | 0 | 1 (7.7) | 5 (1.0) |

Among participants randomized to receive penicillin or azithromycin, 465 (82.7%) were included in the per-protocol analysis with serological data at the 6-month visit. Their mean age was 27.1 years (range, 18.0–53.0 years), and 61.7% were men (Table 2). Most participants were Malagasy and heterosexual. Nearly half (46.9%) had secondary syphilis, 24.7% had primary syphilis, and 28.4% had EL syphilis.

Table 2.

Bivariate Analysis of Characteristics Associated With Serological Cure and Serofast Status at 6 Months

| Characteristic | Serological cure, no. (%) of participants (n = 369) | Serofast status, no. (%) of participants (n = 96) | OR (95% CI) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 234 (81.5) | 53 (18.5) | 1.41 (.89–2.22) |

| Female | 135 (75.8) | 43 (24.1) | 1 |

| Age, years | |||

| ≤24 | 198 (86.8) | 30 (13.2) | 3.30 (1.67–6.54) |

| 25–29 | 84 (83.2) | 17 (16.8) | 2.47 (1.15–5.33) |

| 30–39 | 51 (62.2) | 31 (37.8) | 0.82 (.40–1.69) |

| ≥40 | 36 (66.7) | 18 (33.3) | 1 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black | 54 (83.1) | 11 (16.9) | 1 |

| White or other | 11 (78.6) | 3 (21.4) | 0.75 (.18–3.13) |

| Malagasy | 304 (78.8) | 82 (21.2) | 0.76 (.38–1.51) |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Homosexuala | 12 (85.7) | 2 (14.3) | 1 |

| Heterosexual | 353 (79.3) | 92 (20.7) | 0.64 (.14–2.91) |

| Bisexual | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 0.25 (.02–2.58) |

| No. of sex partners in past 6 months | |||

| 0–1 | 135 (84.4) | 25 (15.6) | 1 |

| 2–5 | 182 (81.6) | 41 (18.4) | 0.82 (.48–1.42) |

| 6–10 | 32 (69.6) | 14 (30.4) | 0.43 (.20–.90) |

| >10 | 20 (55.6) | 16 (44.4) | 0.23 (.11–.51) |

| History of syphilis | |||

| No | 50 (65.8) | 26 (34.2) | 1 |

| Yes | 21 (63.6) | 12 (36.4) | 0.91 (.39–2.14) |

| Unknown/test not performed | 298 (83.7) | 58 (16.3) | 2.67 (1.54–4.64) |

| Other medical conditionsb | |||

| No | 207 (80.5) | 50 (19.5) | 1 |

| Yes | 162 (77.9) | 46 (22.1) | 0.85 (.54–1.33) |

| Syphilis stage | |||

| Primary | 100 (87.0) | 15 (13.0) | 1 |

| Secondary | 187 (85.8) | 31 (14.2) | 0.91 (.47–1.76) |

| Early latent | 82 (62.1) | 50 (37.9) | 0.25 (.13–.47) |

| Baseline RPR titer | |||

| ≤1:32 | 126 (62.7) | 75 (37.3) | 1 |

| >1:32 | 243(92.1) | 21 (8.0) | 6.89 (4.06–11.70) |

| Treatment regimen | |||

| Benzathine penicillin | 182 (79.1) | 48 (20.9) | 1 |

| Azithromycin | 187 (79.6) | 48 (20.4) | 1.03 (.66–1.61) |

| Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction | |||

| No | 223 (77.2) | 66 (22.8) | 1 |

| Yes | 146 (83.9) | 28 (16.1) | 1.54 (.95–2.52) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; RPR, rapid plasma reagin.

Homosexual participants included 12 men who had sex with men and 2 women.

Other medical conditions included any other significantly relevant medical problems reported by participants that involved ≥1 organ systems.

The proportions of evaluable participants who exhibited serological cure varied by syphilis stage and time point after therapy. Overall, the rate of serological cure was 75.1% (349/465) at 3 months and 79.4% (369/465) at 6 months. For primary and secondary syphilis, 84.5% (98/116) and 82.5% (179/217), respectively, exhibited serological cure by 3 months after treatment, with a slight increase to 87.0% and 85.8%, respectively, at 6 months. For participants with EL syphilis, however, a much lower proportion of 54.5% (72/132) had serological cure at 3 months, with only another 5.9% progressing to serological cure at 6 months (62.1% overall).

Characteristics Associated With Serological Cure

We compared characteristics of the 396 participants with serological cure to characteristics of participants with serofast status at 6 months after therapy (Table 2). Age <30 years was associated with increased odds of serological cure. Having a baseline RPR titer >1:32 was associated with a >6-fold increased probability of serological cure, compared with having a baseline RPR titer ≤1:32. Participants with EL syphilis had decreased odds of cure at 6 months, compared with persons with primary syphilis. A decreased odds of serological cure was also evident for participants with >5 sex partners in the past 6 months, compared with participants with ≤1 sex partner. Sex, race, history of syphilis, sexual orientation, history of other medical conditions, treatment regimen, or having a J-H reaction were not significantly associated with serological cure.

Multivariate analysis was conducted, including age and log2 baseline RPR titers as continuous variables, number of sex partners, and stage of syphilis. Because there was a trend toward an association with a J-H reaction after treatment (P = .08), this variable was also included in multivariate modeling. Interactions between age and J-H reaction and between log-transformed baseline RPR and stage entered the model, with P values of <.10. Having >5 sex partners in the past 6 months, relative to ≤1 sex partner, remained negatively associated with serological cure (Table 3). There was an association between age and serological cure that was observed in participants with and those without a J-H reaction; the age dependence was stronger in the former group and equivalent to a 0.88 reduction in the AOR for each 1-year increase in age. A J-H reaction after treatment resulted in a >2-fold increased odds in favor of a serological cure at 6 months for participants at age 27.1 years, the mean age of the study group. Secondary and EL syphilis were both negatively associated with cure at 6 months, compared with primary syphilis. Each 2-fold increase in baseline RPR titer was positively associated with the probability of serological cure for participants with any stage of early syphilis, with the qualitative interaction resulting in a more pronounced effect in the group with secondary syphilis (AOR, 3.15 [95% CI, 2.14–4.65]), compared with the groups with primary or EL syphilis.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Characteristics Associated With Serological Cure in Multivariate Analysis Assessing Main Effects and Interactions

| Parameter | AOR (95% CI) |

| No. of sex partners | |

| 2–5 vs 0–1 | 0.55 (.27–1.10) |

| 6–10 vs 0–1 | 0.25 (.09–.69) |

| >10 vs 0–1 | 0.12 (.04–.34) |

| Agea | |

| No J-H reaction | 0.98 (.94–1.01) |

| J-H reaction | 0.88 (.82–.94) |

| J-H reaction at mean age (27.1 years) | 2.49 (1.24–4.97) |

| Syphilis stage at mean log2 baseline RPR titerb | |

| Early latent vs primary | 0.14 (.04–.43) |

| Secondary vs primary | 0.25 (.08–.78) |

| Mean log2 baseline RPR titerb | |

| Primary syphilis | 1.83 (1.25–2.70) |

| Secondary syphilis | 3.15 (2.14–4.65) |

| Early latent syphilis | 1.86 (1.44–2.40) |

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval, J-H, Jarisch-Herxheimer; RPR, rapid plasma reagin.

Age was assessed as a continuous variable.

The mean log2 baseline RPR titer of 5.7 was used to assess the odds ratio for syphilis stage.

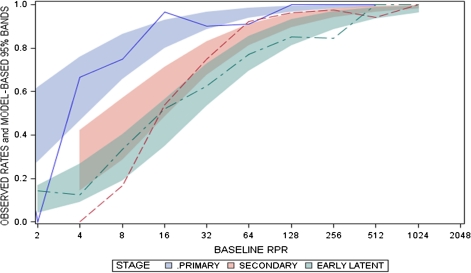

Serological Response Based on Baseline RPR

At 6 months after therapy, serological cure was attained in 62.7% of 201 participants with baseline RPR titers ≤1:32, in 90.6% of 180 participants with titers of 1:64 to 1:128, and in 95.2% of 84 participants with titers ≥1:256. A relationship between serological response and syphilis stage was evident for observed cure rates (Figure 2). Overall, participants with early syphilis and baseline RPR titers ≥1:64 had higher cure rates than those with lower RPR titers. However, in the presence of lower baseline titers, there was a higher probability of cure for participants with primary syphilis than for those with secondary or EL syphilis. Stratification of serological response on the basis of baseline RPR and stage of syphilis yielded similar results. Among participants with baseline titers of ≤1:32, the proportion who remained serofast at 6 months was 58.2% in the group with secondary syphilis and 42.7% in the group with EL syphilis; the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Serological cure as a function of baseline rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titer and stage of syphilis. The proportion or observed probability of cure was computed using logistic regression as a function of the baseline RPR titer and stage of syphilis (primary, secondary, and early latent [EL] syphilis). Colored bands represent 95% confidence intervals around each value of the baseline RPR titer for each stage of syphilis, with smaller bands for titers representing a larger proportion of baseline values from study participants. Overall, participants with early syphilis and baseline RPR titers ≥1:64 had higher cure rates than those with lower RPR titers. There was a higher probability of cure for participants with baseline titers ≤1:32 and primary syphilis, compared with participants with secondary or EL syphilis.

DISCUSSION

Despite the challenges in the interpretation of serological test results, change in nontreponemal titers and clinical response are the most widely used criterion for evaluation of the response to syphilis treatment. The basis for using serological response is derived from trials conducted >40 years ago to compare different therapeutic regimens for primary and secondary syphilis [9, 10]. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic evaluation to assess factors that differentiate HIV-negative individuals from those without serological response, using data from a large, prospective, controlled trial. As such, our findings may serve to guide clinicians regarding both the intensity of syphilis follow-up and the identification of patients who may become serofast after therapy without clear evidence of treatment failure. We found that serological cure was independently associated with young age, fewer sex partners in the past 6 months, earlier stage of infection, higher baseline RPR titers, and a J-H reaction after treatment. A relationship between the stage of infection and the baseline RPR titer was evident in predicting treatment response, because participants with primary syphilis had a higher proportion of serological cure, whereas 43%–58% of patients with secondary or EL syphilis and baseline titers ≤1:32 were serofast at 6 months after treatment.

Given that one-fifth of patients treated for early syphilis did not meet the criteria for serological cure at 6 months, it is important to consider the optimal time point for assessment of serological response. Prior studies evaluating rates of decline in nontreponemal titers after treatment for primary or secondary syphilis suggested that a 4-fold decline in VDRL titers at 3 months or an 8-fold decline at 6 months represented the earliest possible times to ascertain treatment response [10]. However, Brown et al [10] limited their analyses to patients with primary and secondary syphilis with titers between 1:4 and 1:128, which would have excluded more than one-third of our participants who had baseline titers below or above this range. Thus, our data not only confirm previous observations but extend them to a larger sample of patients. We found that 75% of participants with early syphilis had achieved serological cure 3 months after treatment and that there was not a marked further increase at 6 months, suggesting that the likelihood of a substantial decline in the serofast proportion over time is low.

Patients with syphilis who have not achieved the desired serological response and remain serofast represent a clinical challenge. Whether the serofast condition represents persistent infection or variability in host response is unknown. Syphilologists in the 1940s suggested that 4 factors affected syphilis treatment response: (1) the patient, (2) the invading parasite, (3) factors such as intercurrent infection and pregnancy, and (4) treatment [11]. Several investigators have evaluated the effect of HIV infection and treatment regimens on serological response [3, 9, 10, 12, 13]; however, only a few retrospective studies have assessed other factors [14, 15]. Romanowski et al [14] reported that patients with high pretreatment titers had a greater rate of decline than those with lower titers but were less likely to serorevert to negative. They also found that patients experiencing a repeat infection of early syphilis were less likely than those with initial infections to have seroreversion [14]. Another retrospective study involving both HIV-positive patients and HIV-negative patients found that men and persons in the late stage of syphilis had a slower treatment response [15]. HIV-infected persons have been shown to have a slower decrease in RPR titers after syphilis treatment, compared with HIV-negative patients [3].

In our study, we found no association between serological response and sex or history of syphilis, but participants who were younger or reported fewer sex partners had a higher likelihood of serological cure than those who were older or reported multiple partners. A retrospective analysis of HIV-negative syphilitic patients from Kaiser Permanente also reported that older age was associated with a decreased likelihood of reduction in RPR titers [16], which may be due to increasing senescence of the immune system [17]. Interestingly, having a J-H reaction, which is a possible marker of T. pallidum killing with treatment [18, 19], was independently associated with cure. The effect of number of sex partners on serological response has not been reported before, and further study to understand this association is merited.

Data from earlier studies indicate that higher penicillin doses do not significantly change the serofast proportion after treatment [9], which we did not evaluate in our trial. Rolfs et al [3] conducted a randomized trial involving treatment of early syphilis with either benzathine penicillin alone or supplemented with high-dose amoxicillin and probenecid to achieve higher drug levels in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid. These investigators reported serofast rates comparable to those in our participants through 12 months of follow-up.

A principal question in understanding the effect of quantitative nontreponemal titers for predicting treatment response is the extent to which they reflect the activity of the disease process or the immune response. Nontreponemal antibody titers are considered to correlate with disease activity [2]. However, we found that participants with higher baseline titers were more likely to achieve serological cure. This observation is best explained by findings from Baker-Zander et al [20], who demonstrated that VDRL-immunized rabbits exhibited partial protection against reinfection with T. pallidum. These investigators hypothesized that high VDRL antibody titers may help control the infection and facilitate clearance of organisms from persons with early infections. If so, higher baseline nontreponemal titers may signify a beneficial inflammatory and immune response to T. pallidum. Recently, other investigators attempted to distinguish the cellular response in syphilitic patients after treatment by analyzing the proportions of T lymphocytes and natural killer cells [21]. They found no differences in cell types or proportions among individuals with serofast status or seroreversion after treatment, compared with normal controls. Further investigations are essential to elucidate the biological basis for the serofast state and to determine whether serofast patients should undergo continued serological monitoring, retreatment, or cerebrospinal fluid examination for T. pallidum involvement.

Several study limitations should be acknowledged, including our use of combined data from participants treated with penicillin or azithromycin. Concerns about the use of azithromycin and its potential for treatment failures may yield questions about the generalizability of our findings to syphilitic patients treated with penicillin. However, we found no differences in serological response between treatment arms, and we removed participants who did not respond to treatment from our analysis. Our findings may not be applicable to patients treated with doxycycline, because the number of such participants in our study was small. We excluded participants who were pregnant, were HIV positive, had primary syphilis without reactive serologies, had late latent syphilis, or had neurosyphilis. Additional studies involving other populations, such as HIV-infected persons, are needed to assess the relationships between baseline RPR titers and stage of syphilis.

Our analyses were limited, because all participants who had a change in protocol status or were serofast at the 6-month evaluation were retreated with benzathine penicillin. We retreated these patients despite the lack of data to support this practice, because of the uncertainty of follow-up and the theoretical possibility of treatment failure over time. In the trial by Rolfs et al [3], which required 12 months of follow-up after syphilis treatment, only 52% of patients returned at 1 year, demonstrating the difficulty of retaining participants over time. Our results may have been different if we had extended the time to achieve our primary outcome to 12 months; however, improved strategies to increase study retention would be necessary to determine long-term outcomes and/or to assess potential benefits of retreatment after 6 months of follow-up.

The interpretation of quantitative nontreponemal titers after therapy will probably continue to perplex clinicians as they ponder the true significance of the serofast state and the optimal management of serofast patients. We identified key factors associated with serological response to syphilis treatment, using data from a large prospective study, which have implications for the management of early syphilis and expected outcomes after therapy. The CDC’s guidelines for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases [2] have categorized serological follow-up on the basis of stages of infection, but the additional effect of the baseline nontreponemal titer on response to treatment should be considered.

Notes

Acknowledgments.

We are grateful to Pfizer for contributing to early protocol development and providing the azithromycin and doxycycline for the study. We also thank the following: Carolyn Deal, PhD, Nancy Padian, PhD, and Peter Wolff, MHA, Sexually Transmitted Infections Clinical Trials Group Executive Committee; Willard Cates, MD, MPH, Myron Cohen, MD, and Walter E. Stamm, MD, Sexually Transmitted Diseases Clinical Trials Unit Executive Committee; Emil Gotschlich, MD, Kenyon Burke, EdD, Helen Lee, PhD, Larry Moulton, PhD, and Peter Rice, MD, Data Safety and Monitoring Board; Lihan Yan, Melinda Tibbals, Robin Cessna, Carol Smith, and Jamie Winestone, EMMES Corporation; Nincoshka Acevedo, BS, Florence Carayon, MA, and Jill Stanton, BA, Family Health International; Carol Langley, MD, and Janet N. Arno, MD, Indiana University School of Medicine; Tomay Mroczkowski, MD, Stephanie Taylor, MD, and Barbara Smith, RN, Louisiana State University; Carolyn Deal, PhD, Penny Hitchcock, DVM, Barbara Saverese, RN, and Peter Wolff, MHA, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease; Joan Stephens, RN, Anna Lee Hughes, RN, Tracey Burkett, CRNP, Connie Lenderman, MT (ASCP), MBA, Paula B. Dixon, Grace Daniels, and Sharron Hagy, University of Alabama at Birmingham/Jefferson County Department of Health; Heidi Swygard, MD, Karen Lau, FNP, and Christopher Bernart, PA, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Bodo Sahondra Randrianasolo, MD, Mbolatiana Soanirina, MD, Michèle Raharinivo, Felasoa Noroseheno Ramiandrisoa, MD, Ny Lovaniaina Rabenja, MD, Herinjaka Andrianasolo, Roméo Rakotomanga, Tahiana Rasolomahefa, Norbert Ratsimbazafy, MD, Zo Fanantenana Raharimanana, MD, Verolanto Ramaniraka, MD, Marina Rakotonirina, Tiana Ravelohanitra, Andrianiseta Rakotomihanta, Jacqueline Hortensia Rajaonarison, Lucienne Rasoamanana, Elyse Rasoanijanahary, Charlotte Razanasolonambinina, Olivier Claret Raoelina, MD, Naina Ranaivo, MD, Angele Zanatsoa, Claire Fety, Cynthai Mamy, Bruno Raoelina, Esther Solovavy, Justine, Julienne Rasoamarovavy, Diana Ratsiambakaina, MD, Agnè Ramaroson, MD, Theodosie Tombo, David Noelimanana, Florence Raeliarisoa, Gilbert Razaka Sadiry, Bacar Soumaely, Bernard, Justin Ranjalahy Rasolofomanana, Lala Rakotondramasy, Falimanantsoa Sylvain Ramandiarivony, Hobitiana Rakotoarimanan, and Lucie Razanamiandrisoa, University of North Carolina, Madagascar; Jocelyne Andriamiadana, MD, USAID Madagascar; and Institut Pasteur de Madagascar, Ministry of Health, Madagascar.

Financial support.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (contracts N01 A1 75329 to STD Clinical Trials Unit, Myron Cohen, MD, principal investigator and HHSN 26620040073C to STI Clinical Trials Group, Edward W. Hook, III, MD, principal investigator).

Potential conflicts of interest.

All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:187–209. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2010;58(RR–12):26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rolfs RT, Joesoef MR, Hendershot EF, et al. A randomized trial of enhanced therapy for early syphilis in patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. The Syphilis and HIV Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:307–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707313370504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hook EW, Behets F, van Damm K, et al. A phase III equivalence trial of azithromycin vs benzathine penicillin for treatment of early syphilis. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1729–35. doi: 10.1086/652239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hook EW, 3rd, Martin DH, Stephens J, Smith BS, Smith K. A randomized, comparative pilot study of azithromycin versus benzathine penicillin G for treatment of early syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:486–90. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riedner G, Rusizoka M, Todd J, et al. Single-dose azithromycin versus penicillin G benzathine for the treatment of early syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1236–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsen SA, Pope V, Johnson RE, Kennedy EJ., Jr . A manual of tests for syphilis. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Damme K, Behets F, Ravelomanana N, et al. Evaluation of azithromycin resistance in Treponema pallidum specimens from Madagascar. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:775–6. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bd11dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroeter AL, Lucas JB, Price EV, Falcone VH. Treatment for early syphilis and reactivity of serologic tests. JAMA. 1972;221:471–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown ST, Zaidi A, Larsen SA, Reynolds GH. Serological response to syphilis treatment: a new analysis of old data. JAMA. 1985;253:1296–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore JE. The modern treatment of syphilis. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Charles C Thomas Books; 1941. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghanem KG, Erbelding EJ, Cheng WW, Rompalo AM. Doxycycline compared with benzathine penicillin for the treatment of early syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:e45–e49. doi: 10.1086/500406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong T, Singh AE, De P. Primary syphilis: serological treatment response to doxycycline/tetracycline versus benzathine penicillin. Am J Med. 2008;121:903–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romanowski B, Sutherland R, Fick GH, Mooney D, Love EJ. Serologic response to treatment of infectious syphilis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:1005–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-12-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, Fernandez Guerrero ML, Lujan R, Fernandez Tostado S, de Gorgolas M, Requena L. Factors determining serologic response to treatment in patients with syphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1505–11. doi: 10.1086/644618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horberg MA, Ranatunga DK, Quesenberry C, Klein DB, Silverberg MJ. Syphilis epidemiology and clinical outcomes in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected patients in Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:53–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b6f0cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovaiou RD, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Age-associated changes within CD4+ T cells. Immunol Lett. 2006;107:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown ST. Adverse reactions in syphilis therapy. J Am Vener Dis Assoc. 1976;3:172–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farmer TW. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in early syphilis treated with crystalline penicillin G. JAMA. 1948;138:480–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.1948.02900070012003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker-Zander SA, Shaffer JM, Lukehart SA. VDRL antibodies enhance phagocytosis of Treponema pallidum by macrophages. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1100–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Wang LN, Zuo YG, et al. Clinical analysis and study of immunological function in syphilis patient with seroresistance. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009;89:813–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]