Abstract

Stress is common among college students and associated with adverse health outcomes. This study used the social networking Web site Facebook to identify self-reported stress and associated conditions among college students. Public Facebook profiles of undergraduate freshman at a large Midwestern State University (n = 300) were identified using a Facebook search. Content analysis of Facebook profiles included demographic information and displayed references to stress, weight concerns, depressive symptoms, and alcohol. The mean reported age was 18.4 years, and the majority of profile owners were female (62%). Stress references were displayed on 37% of the profiles, weight concerns on 6%, depressive symptoms on 24%, and alcohol on 73%. The display of stress references was associated with female sex (odds ratio [OR], 2.81; confidence interval [CI], 1.7–4.7), weight concerns (OR, 5.36; CI, 1.87–15.34), and depressive symptoms (OR, 2.7; CI, 1.57–4.63). No associations were found between stress and alcohol references. College freshmen frequently display references to stress on Facebook profiles with prevalence rates similar to self-reported national survey data. Findings suggest a positive association between referencing stress and both weight concerns and depressive symptoms. Facebook may be a useful venue to identify students at risk for stress-related conditions and to disseminate information about campus resources to these students.

Keywords: College students, Facebook, Internet, Social networking sites, Stress

Stress is becoming more common among college students; a 1999 survey of US college freshman found that 30% of students reported feeling frequently overwhelmed, an increase from 16% in 1985.1 While more than two-thirds of college students experience some type of stress, 38% of female college students and 27% of males report that their stress level is so high that it negatively affects their academic performance.2,3 Common sources of stress in college students include classes, illness or death of a loved one, relationships, debt, and conflict with roommates or parents. A third of students experience three or more major life stressors each year, and an increase in number of stressors is associated with increased use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana.2

High levels of chronic stress are linked to negative health outcomes including an increased risk of obesity, heart disease, cancer, Cushing syndrome, anorexia nervosa, and chronic fatigue syndrome, among other illnesses.4 Challenges with weight, including binge eating, disordered eating, anorexia nervosa, and overeating, have been linked to high levels of stress and stressful life events.4–7 Increased levels of stress also are associated with depression and anxiety disorders.2,8 Controversies exist regarding links between alcohol use and stress. Although studies report that alcohol use in response to stress is associated only with certain coping styles, perceived stress has been shown to be a predictor of high-risk alcohol use.9–14 Thus, intense or extended stress may be both psychologically and physiologically harmful.

Although stress is common and consequential in college students, many college students are unaware of student health resources for evaluation and stress relaxation treatment resources. More than a quarter of all college students report that they feel unable to manage their stress.2 Because many college students do not visit clinics where stress assessments may be performed, methods of identifying students who may be experiencing adverse consequences from stress remain elusive.2

An innovative method to investigate stress and associated conditions among college students may be social networking sites (SNSs), which are increasingly popular among college students. Social networking sites are Web sites that allow users to create a personal Web profile and communicate with peers. The majority of college students report maintaining an SNS profile, with as many as 98% of students reporting use of a Facebook profile.15 Facebook.com (Facebook Inc, Menlo Park, CA) is currently the most widely used SNS in the United States and has more than 500 million active users worldwide.16,17 College students report using Facebook.com for an average of 30 minutes each day.18

Facebook provides a unique view of college students’ lives in a public, online setting. Facebook includes a popular feature called “status update,” which allows members to display a short description of their current location, emotion, or activity. Status updates of a profile owner’s Facebook “friends” are compiled in a live Really Simple Syndication or Rich Site Summary (RSS) feed. RSS feeds gather regularly changing content from different sources on the Internet into one common source. In the Facebook RSS feed, these different sources are unique users’ status updates. Facebook displays also include personal information and photographs of the profile owner, group affiliations, and an optional section named Bumper Stickers, which are downloadable icons given to a profile owner by his/her friends.

Facebook is an innovative tool that is being used to study behavior; stress on Facebook has not yet been investigated.19–23 The purpose of this study was to evaluate undergraduate freshmen’s Facebook profiles for the prevalence of displayed references to stress and conditions that are commonly associated with stress: weight concerns, depressive symptoms, and alcohol. Facebook may present a novel tool to complement current methods of identifying stressed students as it allows a clinician, peer, or researcher to view a snapshot of a subject’s life in a natural environment. The goal of this study was to evaluate whether Facebook might be a useful venue to identify college students at risk for stress-related conditions.

METHODS

Setting

This content analysis was conducted between January 2009 and July 2010. Public Facebook profiles within a large Midwestern State University Facebook network were evaluated. To join a college network, a student must have a registered .edu e-mail address. The default privacy setting of Facebook allows profile content to be accessible to anyone within the profile owner’s Facebook network. This study was determined exempt by the University of Wisconsin institutional review board as only publicly available information was viewed.

Participants

At the time of this study, Facebook displayed profiles in search results whose owners have chosen to have all or part of the profile viewable to the public. The sample was further defined using the following Facebook search criteria: school status of undergraduate, college graduation class of 2012, and high school graduation class of 2008. Profiles were included if they met the following criteria: owner reported graduating from a high school within the United States, age reported as 18 or 19 years old, and profile activity within the past 30 days. Profiles were excluded if either status updates or personal information section was not publicly available.

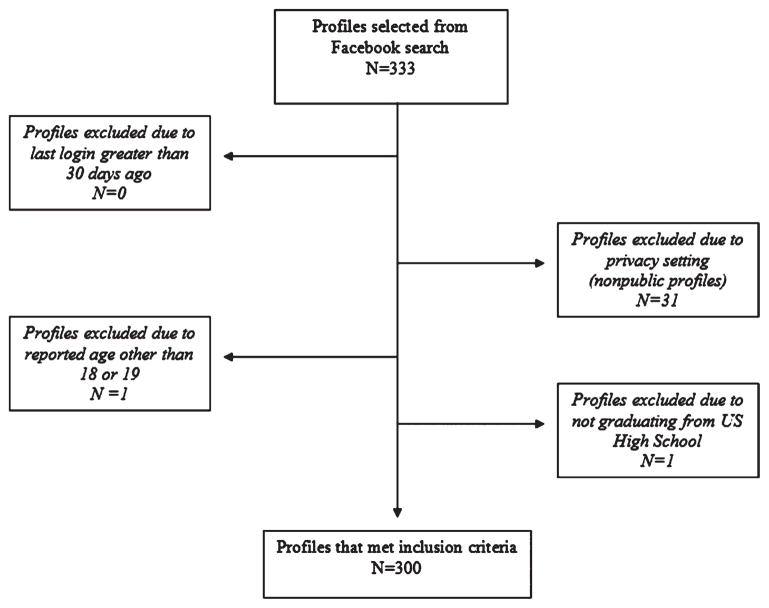

Facebook profiles were evaluated in the order in which the Facebook search engine presented them. Each profile was viewed only one time during the data collection period. A total of 333 profiles were viewed to obtain a target sample size of 300 profiles; 90% of profiles met inclusion criteria. The predominant reason for exclusion was not meeting criteria for privacy settings (31 profiles). One profile was excluded for listing a high school outside the United States, and one profile was excluded because the user’s age was other than 18 or 19 years. All profiles that were viewed had been active in the last 30 days. Figure 1 depicts the profile selection strategy.

FIGURE 1.

Facebook profiles included in the study.

Data Collection and Variables

A systematic investigation was performed of each profile that met inclusion criteria (n = 300). Demographic data, including age, sex, high school, date of profile origin (first activity), and date of most recent activity, which are self-reported in the personal information page or wall of Facebook profiles, were recorded. High school alma mater groupings were as in-state or out-of-state students. Each profile was evaluated for displayed references to stress, weight concerns, depressive symptoms, and alcohol.

Analysis included viewing all publicly available personal information including displayed group affiliations, status updates, bumper stickers, and any photographs of the profile owner. Groups consist of a Facebook page that is made to represent an interest or other commonality that Facebook members may share. Members can join public groups or may be invited to join private groups. Members may then contribute to the group page by posting on the profile wall, adding pictures, or discussing common interests. An example of a group might be “Students who like hiking” or “The group for people who like scary movies.” Status updates allow users to post short text updates to display to all friends on their profile wall and in the Facebook RSS feed. Facebook formerly prompted users with the question: “What are you doing right now?” which changed to “What’s on your mind?” in March 2009 to elicit status updates about current emotions or activities. Examples of status updates are “Evan is going to Spanish class and can’t wait to get outside afterward” or “Mary is feeling sad and missing home.” The application bumper stickers are optional and can be added to Facebook profiles by users. This application allows the user to add graphics that may contain a combination of photographs, text, and logos to their profile. Bumper stickers are user-generated by Facebook users. Friends may give bumper stickers to each other, and this content must be approved by the recipient prior to being displayed on the profile. Photographs are uploaded digital photos that are displayed in albums on Facebook profiles. These photographs can be shared with friends and linked to the profiles of others in the photos through tagging.

When available, the date the reference was displayed online was recorded. Facebook attaches a date stamp to all status updates and photos. The time of the reference was coded as occurring either before entering college (through August 2008) or during college (September 2008 through time of coding).

A code book developed in previous work was adapted.22 The code book defined key terms that were considered references to stress, weight concerns, depressive symptoms, and alcohol use. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition was used to develop key terms used to define depressive symptoms.24 Table 1 contains examples of code words used in identifying references on Facebook profiles. During an initial assessment of a separate pilot set of profiles, biases and criteria for coding were discussed thoroughly. A 10% subset of data was coded by both authors. Cohen κ for interrater reliability for the stress variable was 0.78.

Table 1.

Examples of Code Words Used to Identify References on Facebook Profiles

| Stress references | Stress |

| Overwhelmed | |

| Unable to relax | |

| Weight concern references | Obesity |

| Not eating because of weight | |

| Losing weight | |

| Dieting | |

| Depressive symptom references | Sad |

| Lonely | |

| Depression | |

| Suicide | |

| Crying | |

| Alcohol references | Alcoholic beverages |

| Missing class/activity due to drinking | |

| Drinking too much | |

| Drunk | |

| Hangover |

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 9.0 (2003; Statacorp LP, College Station, TX). We initially selected 300 profiles as the target based on previous work.22 We then evaluated the prevalence of references to key variables after 100 profiles had been coded and compared this prevalence to those determined after 300 profiles had been coded. Noting no statistically significant differences confirmed the sample size decision. Descriptive statistics were calculated to determine prevalence of references to stress, weight concerns, depressive symptoms, and alcohol; these results were then stratified by sex. Logistic regression was used to determine associations between displayed stress variable and displayed weight concerns, depressive symptoms, and alcohol. Associations were adjusted for sex.

RESULTS

The majority of the 300 analyzed Facebook profiles identified as female sex (62%) and age 18 years (61%). Most subjects (82%) were in-state students. Most profiles in the sample had a first date of Facebook activity between 2 and 3 years prior to the date of being examined. The mean number of days since the most recent activity on Facebook for the sample was 1.81 (SD, 3.3) days. The demographic data are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic Data From Facebook Profiles (n = 300)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 185 (62) |

| Male | 115 (38) |

| Age, y | |

| 19 | 116 (39) |

| 18 | 179 (61) |

| High school (alma mater) | |

| In state | 246 (82) |

| Out of state | 54 (18) |

| Date of first Facebook use | |

| 0–1 y ago | 8 (2.7) |

| 1–2 y ago | 79 (26) |

| 2–3 y ago | 210 (70) |

| ≥3 y ago | 3 (1) |

| Days since most recent Facebook use, mean (SD) | 1.81 (3.3) |

Of the 300 profiles, 36.8% included stress references. Stress references were present on 46% of the female profiles and 21% of male profiles in the sample. The majority of stress references were made by females (78%).

Stress references were most commonly displayed in status updates (98%). References to stress displayed before starting college were present on 49% of profiles, and 51% of profiles referenced stress either during college or both before and during college. However, stress references were coded on profiles during college for a period of 6 months, whereas the majority of profiles contained data from at least 2 years of high school. An increase in referencing stress was seen on Facebook profiles when the cohort began college, and a high level of higher level of stress was seen on the profiles during college. This can be seen in Figure 2. There was an average of two stress references per profile of the profiles that contained stress references.

FIGURE 2.

Graph of stress references per month. Graph depicts the total number of stress references made by the cohort of profiles in each grade during the period of October 2006 through February 2009. References made between on or after September 1, 2008, were considered “college” references. References prior to this date were considered “high school” references. The bold box indicates references made by the cohort during college.

References to weight concerns were displayed on 6.4% of profiles; depressive symptom references were present on 24.4% of profiles, and alcohol references on 72.9%. Examples of these references are shown in Table 2.

Female sex was a predictor of referencing stress (odds ratio [OR], 2.81; confidence interval [CI], 1.7–4.7; P < .0001). Profiles that displayed stress references were more likely to also reference weight concerns (OR, 5.36; CI, 1.87 15.34; P = .002) and depressive symptoms (OR, 2.7; CI, 1.57–4.63; P < .0001). The association between referencing stress and referencing alcohol was not statistically significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Examples of References on Facebook Profilesa

| Stress references | “Tami is back at school and already stressed out.” |

| “Kim is stressed and overwhelmed.” | |

| “Cory has a very stressful weekend up ahead.” | |

| Depressive symptoms | “Victoria has been so depressed the past week.” |

| “Pete hates his life and wonders if he has hit bottom yet.” | |

| “Natalie agrees, can we make this suicide pact happen?” | |

| Weight concerns | “Maggie is getting fatter by the minute.” |

| “Julie is trying to lose a few pounds. So don’t feed me!” | |

| “Alex is sick of her diet.” | |

| Alcohol references | “Ben got too drunk last night and is missing class.” |

| “Ashley is embarrassed by the drunk text messages she sent.’ | |

| “Tara is so happy she can drink more Vodka than you.” |

Facebook status updates appear in the third person in RSS feeds. All statements in this table have been changed from actual statements, and no real names of subjects have been used.

DISCUSSION

Conclusions

This study found that stress references on college freshmen’s Facebook profiles are common, particularly among females. Furthermore, an increase in referencing stress is seen from high school to college. This is consistent with previous studies that show that female college students self-report higher levels of stress on surveys than their male peers.25 A 2007 study of University of California freshman found that 38% of females and 17% of males report feeling frequently overwhelmed.26 The similarities found between this study and previous surveys suggest that adolescents who experience stress may use Facebook as an outlet for voicing this stress. This finding could reflect an increased comfort with displaying personal information online compared with surveys, as has been seen in previous studies.27 Students may share concerns about stress in their natural, frequently used environment, and this may lead students to report stress at a lower threshold than they may in a clinical encounter.

There was an association between stress and both weight concerns and depressive symptoms. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have shown that high levels of stress are associated with changes in weight and with the development of mental illness, such as depression and anxiety disorders.6,8 Mental health diagnoses are common among college students, with 17% of students ever having had a diagnosis of depression.28

While study findings suggest similarities between self-reports of stress and weight concerns or depressive symptoms on Facebook, it is worth considering an alternative explanation. Subjects who reference stress on their Facebook profiles may be predisposed to displaying distress publicly and may be more likely to reference stress and a concurrent issue on Facebook than other students.

The lack of a statistically significant association between alcohol references and stress references displayed on Facebook was unexpected. Existing studies show that stress is linked to alcohol use, particularly in males and individuals with certain coping styles.11,29 The study did not identify coping styles of the sample, so this link could not be assessed. A hypothesis for the lack of association is the high prevalence of alcohol references on Facebook profiles, also an unforeseen finding.

The ethical considerations of this novel method of investigating stress warrant discussion.30,31 As this study involved observation of public behavior, it can be compared with observing human interactions in a public setting, such as a park. As with this offline setting, interactions may be observed, although they are not intentional subjects of research.32 However, in contrast to observations in a public park, college students who use Facebook make a choice to make content available to the public versus limiting accessibility through privacy settings.31 Social networking sites are emerging as an important tool for health research, as well as for businesses, as colleges and employers use SNSs to screen potential candidates.19,20,22,33,34

Limitations

This study has several limitations based on the sample population and the use of Facebook as the primary research tool. This study focused on one university; further investigation is needed to learn the applicability to other college populations. Although a 2009 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study found that stress levels in adults differ by state and region in the United States, no known studies have been done to compare the stress levels between students in different universities.35 Second, this study used only one SNS; however, since an estimated 98% of undergraduate students use Facebook, it is likely that the results are representative of the population.15,18 Only publicly available profiles were viewed for this study, although fewer than 10% of profiles were excluded because of privacy settings. Third, it is unknown how Facebook selects profiles that appear in search results; profiles are displayed in a nonalphabetical, nonnumerical list.

Finally, although coding of profiles was completed thoroughly, Facebook profiles are dynamic. Each profile was viewed only one time, so profiles that were observed at the end of the investigation period of the study may have contained more data than profiles observed in the beginning of the study. In addition, Facebook privacy settings have evolved since this study was conducted and warrant review of methods for future studies of this nature.

Implications

Despite the limitations of this study, the results have important implications for college student healthcare and nursing practice. First, of the 333 profiles that were selected to be viewed to find out sample size of 300 profiles, only 31 contained privacy settings that warranted their exclusion from this study. We were surprised to find such a small minority of profiles of college students who had chosen to make all or part of their profile private. Although Facebook is continuously working to improve privacy settings on their Web site, few students in this study showed awareness of the potential implications of having a public profile. General awareness of consequences of having a public Facebook profile, as well as displaying personal information on the Internet, should be promoted among the college student population.

Facebook was targeted during 2009 and 2010 because of privacy concerns and has since revised default settings and attempted to promote awareness of privacy settings. Because of the changes in Facebook privacy settings, searching for Facebook profiles has changed dramatically since these profiles were collected in 2009. Profiles that are fully private no longer appear in Facebook searches for random profiles. The extent that this study could be replicated is unknown, and it is likely that many profiles that were seen in this study have different profile settings.

More than half of college students are interested in receiving information on stress reduction from their college or university.28 Facebook and other SNSs are growing in popularity and are already being used by some healthcare professionals to provide clinical advice and treatment updates to patients.36 Facebook may provide a mode of distribution of targeted stress reduction information to students through features such as public pages, groups, or advertisements and should be considered as a future venue of patient education.

Facebook provides a current and historical snapshot of the experiences and emotions a person chooses to publicly display online. Facebook could be used to complement current stress identification and prevention measures. Social networking sites have been suggested as a method to screen adolescents and college students for health conditions and risk behaviors.30 As healthcare professionals continue to explore the possibilities of using the Internet and SNSs as clinical tools, the possibilities of using Facebook for identification and/or diagnosis of conditions such as stress should continue to be explored.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Susan Zahner and Sarah Van Orman for assistance in manuscript editing and preparation.

The project described was supported by award K12HD055894 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Larson R. The future of adolescence: lengthening ladders to adulthood. Futurist. 2002:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boynton Health Services, University of Minnesota. Health and Academic Performance, Minnesota Postsecondary Students. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College Health Association–National College Health Assessment. Reference group data report (abridged): the American College Health Association. J Am Coll Health. 2009;57:477–488. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.5.477-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. stress system malfunction could lead to serious, life threatening disease. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2002. [Accessed April 5, 2009.]. http://www.nichd.nih.gov/news/releases/stress.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolff GE, Crosby RD, Roberts JA, Wittrock DA. Differences in daily stress, mood, coping, and eating behavior in binge eating and nonbinge eating college women. Addict Behav. 2000;25:205–216. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Economos CD, Hildebrandt ML, Hyatt RR. College freshman stress and weight change: differences by gender. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32:16–25. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greeno CG, Wing RR. Stress-induced eating. Psychol Bull. 1994;115:444–464. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almawi W, Tamim H, Al-Sayed N, et al. Association of comorbid depression, anxiety, and stress disorders with type 2 diabetes in Bahrain, a country with a very high prevalence of type 2 diabetes. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008;31:1020–1024. doi: 10.1007/BF03345642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veenstra MY, Lemmens PH, Friesema IH, et al. Coping style mediates impact of stress on alcohol use: a prospective population-based study. Addiction. 2007;102:1890–1898. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Frone MR, Mudar P. Stress and alcohol use: moderating effects of gender, coping, and alcohol expectancies. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:139–152. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutledge PC, Sher KJ. Heavy drinking from the freshman year into early young adulthood: the roles of stress, tension-reduction drinking motives, gender and personality. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:457–466. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park CL, Armeli S, Tennen H. The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:126–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratliff KG, Burkhart BR. Sex differences in motivations for and effects of drinking among college students. J Stud Alcohol. 1984;45:26–32. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1984.45.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardegna KH. Pro-Quest Information & Learning. 2007. The Relationship Between Perceived Stress, Identity Formation, and Risk-Taking Behavior in College Students. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis K, Kaufman J, Gonzalez M, Wimmer A, Christakis N. Tastes, ties, and time: a new social network dataset using Facebook.com. Soc Netw. 2008;30:330–342. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Site profile for Facebook.com. [Accessed July 15, 2009];2009 http://siteanalytics.compete.com/facebook.com.

- 17. [Accessed July 23, 2010.];500 Million stories. 2010 http://blog.facebook.com/blog.php?post=409753352130.

- 18.Pempek T, Yermolayeva YA, Calvert SL. College students’ social networking experiences on Facebook. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2009;30(3):227–238. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buffardi LE, Campbell WK. Narcissism and social networking Web sites. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2008;34:1303–1314. doi: 10.1177/0146167208320061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Personal information of adolescents on the Internet: a quantitative content analysis of MySpace. J Adolesc. 2008;31:125–146. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livingstone S. Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: teenagers’ use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media Soc. 2008;10:393–411. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno MA, Parks MR, Zimmerman FJ, Brito TE, Christakis DA. Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: prevalence and associations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:27–34. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muise A, Christofides E, Desmarais S. More information than you ever wanted: does Facebook bring out the green-eyed monster of jealousy? Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;12:441–444. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adlaf EM, Gliksman L, Demers A, Newton-Taylor B. The prevalence of elevated psychological distress among Canadian undergraduates: findings from the 1998 Canadian Campus Survey. J Am Coll Health. 2001;50:67–72. doi: 10.1080/07448480109596009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall N, Chipperfield JG, Perry RP, Ruthig JC, Goetz T. Primary and secondary control in academic development: gender-specific implications for stress and health in college students. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2006;19:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleming P. Sofware and sympathy: therapeutic interaction with the computer. In: Fish SL, editor. Talking to Strangers: Mediated Therapeutic Communications. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National College Health Assessment. Fall 2008 reference group data report. American College Health Association; 2009. [Accessed July 30, 2009.]. http://www.acha-ncha.org/docs/ACHA-NCHA_Reference_Group_Report_Fall2008.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hussong AM. Further refining the stress-coping model of alcohol involvement. Addict Behav. 2003;28:1515–1522. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pujazon-Zazik M, Park MJ. To tweet, or not to tweet: gender differences and potential positive and negative health outcomes of adolescents’ social Internet use. Am J Mens Health. 2010;4:77–85. doi: 10.1177/1557988309360819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreno MA, Fost NC, Christakis DA. Research ethics in the MySpace era. Pediatrics. 2008;121:157–161. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyd D. Internet Inquiry: Conversations About Method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. How can qualitative Internet researchers define the boundaries of their projects: a response to Christine Boyd; pp. 26–332. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kluemper DH, Rosen PA. Future employment selection methods: evaluating social networking Web sites. J Manage Psychol. 2009;24:567–580. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farmer AD, Holt C, Cook MJ, Hearing SD. Social networking sites: a novel portal for communication. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:455–459. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.074674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson TF, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Wechsler H. The state sets the rate: the relationship among state-specific college binge drinking, state binge drinking rates, and selected state alcohol control policies. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:441–446. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.043810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vance K, Howe W, Dellavalle RP. Social Internet sites as a source of public health information. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:133–136. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]