Abstract

Over the last decade, left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation has emerged as an alternative treatment strategy in patients with advanced heart failure irrespective of their transplant eligibility. However, success and applicability of this therapy is largely limited by high complication rates associated with these devices. Although superior outcomes have been achieved with the second-generation continuous-flow LVADs, device-related infections continue to be a prevalent complication in this patient population and contribute significantly to the financial burden of this therapy due to an increased need for hospitalizations and surgical interventions. Patient selection, device design and LVAD-induced immune system dysfunction appear to be major risk factors for the development of device-related infections. Improvements in device design and better patient selection strategies, particularly with respect to identifying individuals with genetic susceptibility to device-related infections, may further reduce this prevalent complication and improve outcomes in patients with advanced heart failure.

Keywords: biomaterial, device-related infections, driveline, heart failure, LVAD, pump-pocket

While the population of patients with congestive heart failure has gradually risen to over 5 million Americans and resulted in 282,000 annual deaths, the available transplant population has remained stagnant at approximately 2000 donors per year [1,2]. The significant gap has been filled by the recent advances and implementation of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs). The first-generation pulsatile-flow volume displacement devices and newer generation continuous-flow assist devices have provided a necessary therapy as either a bridge to transplantation or destination therapy in the growing end-stage heart failure population that remains refractory to maximal medical management [3–5]. With a growing number of heart failure patients failing maximal medical management each year, substantial growth in the number of LVAD implantations is anticipated over the next decade.

Despite advances in technology and subsequent improvements in morbidity and mortality of patients undergoing LVAD placement, post-implantation sepsis and device-related infections remain inherent risks inextricably tied to implanting LVADs [3,5]. In the Randomized Evaluation of Mechanical Assistance for the Treatment of Congestive Heart Failure (REMATCH) trial, sepsis accounted for more than twice the number of deaths than did device failure in patients with LVAD (41 vs 17%) [3]. Along with driving higher rates of morbidity and mortality, complications from infections incur significant costs. Oz and colleagues estimated the cost of index hospitalization to be US$119,874. However, these costs more than doubled (US$263,822) when patients developed sepsis, and increased more than sevenfold (US$869,199) when patients developed sepsis, pump-housing infections or perioperative bleeding [6]. As a result of the increasing associated patient risks of morbidity and mortality and ballooning costs incurred, it is imperative to review appropriate strategies for the prevention of infections with mechanical circulatory devices.

Definition & incidence

Device-related infections can be broadly categorized under driveline infections, pump-pocket infections (PPIs) and LVAD-associated endocarditis. Driveline infections occur along the percutaneous lead which connects the LVAD motor to its external power source. Erythema can be the initial sign at the driveline site that may represent the presence of subcutaneous infection and evidence of early cellulitis. However, it may be difficult to differentiate erythema secondary to cellulitis, as opposed to irritation of the surrounding skin. Clinical signs that point towards driveline infection include interval progression of cellulitis, fever, leukocytosis and purulent drainage from the driveline exit site. Since driveline infections can extend into the pump-pocket, these patients should be appropriately imaged for such involvement as a part of their work-up.

Pump-pocket infections occur within the recess that is developed within the abdominal cavity to house the LVAD device. The majority of currently used LVADs are designed to reside either within the abdominal cavity or preperitoneum above the posterior rectus sheath and below the rectus abdominis, and internal oblique muscles. Clinical evidence implicating the presence of PPI may include fever, leukocytosis, abdominal tenderness, as well as persistent purulent drainage from the driveline site [7,8]. Imaging modalities such as CT scan and ultrasound can be used to assess for fluid collections around the device and guide needle aspiration as indicated for cell count, Gram stain and microbiological culture. However, recent evidence suggests that integrated molecular and anatomic hybrid imaging using leukocyte scintigraphy and SPECT/CT may be a more sensitive in early diagnosis of driveline infections and PPIs [9]. Definitive identification of PPIs tends to occur when cultures are taken from fluid drained from the abscess site.

Left ventricular assist device patients with bacteremia/sepsis of unknown source should also be assessed for LVAD-associated endocarditis. Unfortunately, current imaging techniques including echocardiography are limited in their ability to detect LVAD-associated endocarditis. Definitive diagnosis is generally achieved through cultures obtained from the valves and/or internal pump surface following implantation or at autopsy.

Incidence of LVAD-associated infections reported in major clinical trials is summarized in Table 1. As noted in this table, driveline infections occur more commonly than PPIs, which are almost eradicated with the introduction of second- and third-generation LVADs. Since the REMATCH trial in 2001 [3], there has been a remarkable reduction in infectious complications in patients undergoing LVAD implantation.

Table 1.

Device-related infectious complications in major left ventricular assist device trials/registries.

| Trial/registry | Year | Device | Flow pattern | n | BTT/DT | Median duration of support (days) |

Incidence % (patient per year) | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis | Driveline | PPI | ||||||||

| REMATCH | 2001 | HeartMate® VE | Pulsatile | 68 | DT | 408 | 53.7% (0.60) | 36.7% (0.41) | [3] | |

| CUBS | 2007 | LionHeart™ | Pulsatile | 23 | BTT | 112 | 30.4% (0.32) | NA | 30.4% (0.32) | [49] |

| HeartMate II BTT | 2009 | HeartMate II® | Continuous | 133 | BTT | 126 | 20.0% (0.62) | 14.0% (0.37) | 0.0% (0.00) | [50] |

| HeartMate II DT | 2009 | HeartMate II | Continuous | 134 | DT | 621 | 36.0% (0.39) | 35.0% (0.48) | [5] | |

| HeartMate II DT | 2009 | HeartMate® XVE | Pulsatile | 66 | DT | 219 | 44.0% (1.11) | 36.0% (0.90) | [5] | |

| INTERMACS | 2010 | Multiple | Pulsatile | 593 | BTT and DT | NR | 32.0% (NR) | 21.0% (NR) | 7.0% (NR) | [51] |

| ADVANCE | 2010 | HeartWare® | Continuous | 137 | BTT | 228 | 6.4% (0.11) | 10.7% (0.21) | 0.0% (0.0) | [27] |

BTT: Bridge to transplantation; CUBS: Clinical Utility Baseline Study; DT: Destination therapy; INTERMACS: Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support; NA: Not applicable; NR: Not reported; PPI: Pump-pocket infection; REMATCH: Randomized Evaluation of Mechanical Assistance for the Treatment of Congestive Heart Failure.

Factors predisposing to LVAD infection

Patient-related risk factors

Numerous studies in the pulsatile-flow device era have failed to establish a significant relationship between demographic risk factors such as age [10,11], gender [12] or race [13] with the development of driveline infections or PPIs in LVAD recipients. Similarly, these factors do not seem to be related to LVAD-related infections in continuous-flow device recipients [14,15]. Even though it is generally held that metabolic derangements of diabetes may predispose patients to infection, studies have demonstrated comparable driveline infection and PPI rates in diabetic versus nondiabetic LVAD recipients [16,17]. It is important to note that restoration of normal cardiac output following LVAD implantation improves diabetic control in patients with advanced heart failure, which may be at least in part responsible for comparable infection rates observed in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals [18]. Raymond and colleagues have shown that patients with driveline infections had a significantly higher BMI compared with control groups, suggesting that obesity and associated metabolic syndrome may predispose LVAD recipients to device-related infections [19]. Similarly, our institutional experience with continuous-flow device patients revealed a trend toward significance between development of infection and increased BMI [14], while other researchers failed to demonstrate such a relationship [20,21]. Therefore, further studies are warranted to investigate the effect of BMI on the development of device- related infections.

A substantial body of literature suggests that malnutrition is associated with infectious complications, as well as increased mortality in surgical patients. In addition, patients with end-stage heart failure are particularly susceptible to develop malnutrition due to poor nutritional intake, specific metabolic imbalances, as well as elevated serum TNF-α [22,23]. Dang et al. have demonstrated that crude markers of nutritional status including serum albumin, total protein and absolute lymphocyte count were significantly associated with clinical outcomes, including post-implantation sepsis, intensive care unit length of stay, and bridge to transplantation rate, suggesting that malnutrition may complicate care of these patients [24].

Device-related risk factors

Patients requiring LVAD therapy have been historically supported by large, pulsatile, volume-displacement devices (HeartMate® XVE, Novacor and Thoratec), which were associated with significant rates of driveline infections as well as PPIs. However, significant reductions in infection rates were observed with the introduction of second-generation continuous-flow devices into clinical use (HeartMate II®, VentrAssist™ and MicroMed DeBakey) [21,25]. Indeed, a multicenter prospective randomized trial of destination therapy patients showed significantly lower device-related infection rates in HeartMate II recipients compared with HeartMate XVE [5]. A recent report from the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) also suggested that continuous-flow technology was associated with less infection rates than the pulsatile pumps [26]. Lower infection rates in the second-generation devices may be in part attributable to continuous-flow devices having a more compact design with relatively smaller percutaneous driveline. Moreover, continuous-flow devices do not have compliance chambers, polyurethane membranes or prosthetic valves that can serve as nidus for infection. Schaffer and colleagues performed a multivariate regression analysis predicting device-related infections following LVAD implantation, and suggested that year of LVAD implantation rather than the device type is associated with the development of device-related infections [15]. Therefore, improvements within LVAD patient care systems, resulting in earlier diagnosis and treatment of potential post-implantation complications have possibly contributed to overall reduction in device-related infections in these individuals. More recently, use of a third-generation centrifugal LVAD implanted in the pericardial cavity eliminating the need for pump-pocket (HeartWare® device, HeartWare International, Inc.) was associated with lower rates of device-related infection compared with historical controls [27]. On the other hand, the Clinical Utility Baseline Study (CUBS) trial previously demonstrated that use of a totally implantable LVAD system, eliminating the need for driveline, was associated with lower infection rates. Taken together, these data suggest that device design has a significant impact on the incidence and type of device-related infection.

Zierer and colleagues performed a multivariate analysis of patients undergoing pulsatile LVAD implantation and identified duration of support, as well as trauma at the driveline exit site, as independent predictors of late driveline infection [28]. This finding is particularly important since an increasing number of patients will be implanted with LVADs for destination therapy within the next decade. Interestingly, in our institutional experience, patients undergoing LVAD implantation for destination therapy showed a trend towards increase in infection after LVAD implantation compared with bridge to transplant patients, which was attributed to longer duration of support in these patients [14].

Immune system defects

In addition to patient- and device-related risk factors, it appears that LVAD-induced alterations in the host immune system may significantly contribute to the development of device-related infections following LVAD implantation. Itescu’s group from Columbia University have demonstrated that patients on LVAD support demonstrate lymphopenia with a selective reduction in CD4+ T cells and CD4+/CD8+ ratio compared with medically treated New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class IV heart failure patients [29]. At the cellular level, circulating peripheral mononuclear cells obtained from LVAD patients showed defective proliferative responses in vitro upon activation with various stimuli including phytohemagglutinin-P, anti-CD3 and staphylococcal enterotoxin B [30,31]. In addition, both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations demonstrated significantly higher levels of apoptosis, as defined by annexin V reactivity, compared with medically treated patients, which is at least in part mediated by activation of the CD95 (Fas) signaling in these patients [29,30]. Moreover, staphylococcal enterotoxin B challenge in CD3+ cells from LVAD patients showed significantly fewer CD3+ cells expressing IL-2 and TNF-α and higher numbers of CD3+ cells upregulating IL-10 than control patients by flow cytometry, suggesting a downregulation of proinflammatory cytokine expression, and an upregulation of suppressive cytokine expression [31,32].

In addition to T-cell defects, it has been shown that LVAD-derived biomaterials induce activation of B cells in vitro through calcineurin and CD40 ligand-dependent T-cell activation pathways [33]. Indeed, patients with LVAD demonstrated B-cell hyper-reactivity with significantly higher frequency of circulating antiphospholipid antibodies, as well as IgG antibodies against MHC class I and II antigens in vivo [33]. Taken together, these findings suggest that defects in T-cell function and cellular immunity accompanied by polyclonal B-cell hyper-reactivity observed in LVAD patients may lead to increased infectious complications in these patients.

It is important to point out that the aforementioned studies investigating the defects in the immune cell compartments were performed in patients undergoing pulsatile-device support and the findings may not be applicable to continuous-flow device patients. One study investigating lymphocyte function in six patients undergoing continuous-flow device implantation (DeBakey LVAD) demonstrated gradually increasing annexin V reactivity in circulating CD3+ T lymphocytes up to 4 weeks post-implantation, which was normalized by 7 weeks on LVAD support [34]. Moreover, the CD4/CD8 ratio was unchanged in the post-implantation period, suggesting that the defects in the immune system may be less severe in continuous-flow device patients. Future studies are warranted to investigate the precise mechanisms for the differential effects of pulsatile versus continuous- flow LVADs on the immune system.

Microbiology of LVAD infections

Numerous studies performed microbiological assessment of LVAD-related infections (Table 2). These studies identified Gram-positive organisms, particularly Staphylococcus and Enterococcus species, as the major culprit for both driveline infections and PPIs. Pseudomonas species appear to be the most common Gram-negative pathogen causing LVAD-related infections. Interestingly, microbiological profile does not seem to differ in pulsatile versus continuous-flow device patients. Although not as common, fungal pathogens – particularly Candida species – can cause driveline, pump-pocket, as well as LVAD-associated endocarditis in susceptible individuals [14,35–37]. These organisms are highly resistant to both innate and adaptive host defense mechanisms by forming a polysaccharide biofilm that serves to protect them from leukocytes, complement, antibodies and antimicrobial therapies [8]. In addition, the majority of these pathogens may be drug resistant and impose a challenge in the eradication of LVAD-related infections [14].

Table 2.

Most common pathogens isolated in left ventricular assist device-related infections.

| Study (year) | Device | Source of culture | Isolated pathogen or species | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | #2 | #3 | ||||

| Herrmann et al. (1997) | Novacor N100 | Device surface/pocket | Staphylococcus aureus | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Enterococcus faecalis | [52] |

| Sinha et al. (2000) | HeartMate® | Device surface/driveline/pocket | Staphylococcus | Pseudomonas | Propionibacterium | [45] |

| Simon et al. (2005) | HeartMate | Driveline Device pocket |

S. aureus MRSE |

S. epidermidis S. aureus |

E. faecalis | [35] |

| Gordon et al. (2001) | HeartMate/Novacor | Bloodstream | S. aureus | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Enterococci | [53] |

| Monkowski et al. (2007) | HeartMate/Thoratec | Driveline Device pocket |

S. aureus S. aureus |

Enterococci Enterococci |

Klebsiella | [36] |

| Zierer et al. (2007) | HeartMate/Novacor | Driveline | S. aureus | S. epidermidis | Corynebacterium jejunii | [28] |

| Topkara et al. (2010) | HeartMate II®/VentrAssist™ | Driveline | MRSA | P. aeruginosa | [14] | |

| Schaffer et al. (2011) | HeartMate XVE/HeartMate | Driveline Device pocket |

Staphylococcus Staphylococcus |

Pseudomonas Enterococci |

Serratia Pseudomonas |

[15] |

MRSA: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MRSE: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis.

Management of patients with LVAD infections

Driveline infections & PPIs

When infection of the driveline site is suspected, prompt culture and Gram stain of the site, along with blood cultures, should be obtained prior to the initiation of empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics that are tailored to flora including Staphylococcus and Pseudomonas species [14]. Additional imaging studies should be considered early in the course for assessment of fluid accumulations for a possible extension to deep tissue as well as pump-pocket. Consultation of infectious disease specialists can be beneficial when attempting to tailor therapy, particularly with respect to institution-specific guidelines and deciding on ultimate treatment durations. Although driveline infections can be managed through administration of systemic antibiotics, surgical drainage and incision of driveline site with driveline revision may be required to remove dead tissue and allow for faster wound healing and recovery. Vacuum-assisted closure devices have been successfully applied in select driveline infection cases as an adjuvant to antibiotic therapy; however, the efficacy of this method remains to be tested in larger patient cohorts [38,39]. Inpatient intervention is generally preferred; however, it has been possible to treat some patients on an outpatient basis using oral antibiotics.

Initial management of PPIs is similar to management of driveline infections with prompt cultures and the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Imaging typically demonstrates the presence of fluid surrounding the device when PPIs occur, generally requiring exploration of the pocket site through surgical incision and drainage. Use of antibiotic-impregnated beads applied locally to the pump-pocket has been suggested as an alternative therapy with less systemic side effects in select cases [40]. The presence of Gram-negative bacteria or yeast can require more invasive management and complete revision of the driveline tract [41]. Severe cases of pump-pocket or mediastinal infections with tissue defects may benefit from use of muscle or omental transposition flaps, although these procedures are associated with a high risk of mortality [42,43]. Intractable cases may require device explanation, particularly in the presence of LVAD-associated endocarditis. While there is no data to support any specific approach to therapy of LVAD-associated endocarditis, clinical decision-making for device exchange or explantation is generally based on the patient’s overall status including, but not limited to, presence of sepsis, end-organ dysfunction, progressive cachexia and/or septic emboli.

Effect of LVAD-related infections on outcomes

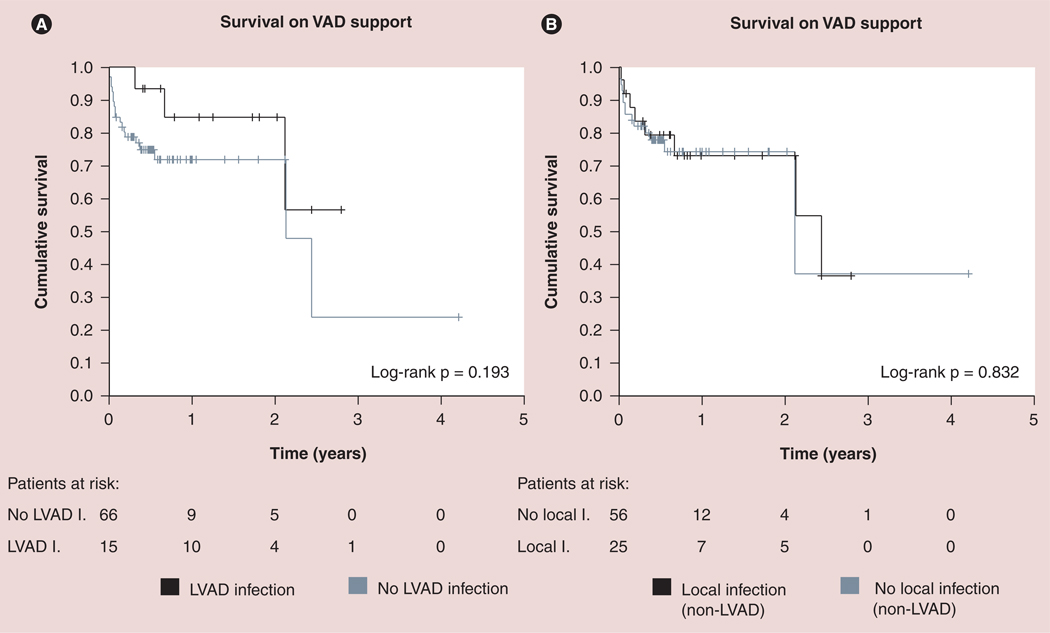

Analysis of infection outcomes in the REMATCH trial patients demonstrated that survival among LVAD recipients with post-implantation sepsis was significantly lower than those without sepsis [44]. On the other hand, device-related infections, particularly pump-pocket and driveline, appear to have no significant impact on post-implantation survival, bridge to transplantation success and post-transplantation survival [35,45,46]. Similarly, our institutional experience with continuous-flow patients revealed no effect of device-related infection on post-implantation survival (Figure 1) [14]. However, it is important to note that LVAD infections lead to increased morbidity and cost due to need for hospitalizations and surgical procedures. Zierer et al. suggested that number and duration of readmission to the hospital significantly increased in pulsatile device patients with late driveline infections [28]. Device-related infections also appear to be the primary indication of hospital readmission in patients with continuous-flow LVADs [Topkara VK et al., Unpublished data]. Although driveline infections and PPIs do not have a significant impact on mortality, LVAD-associated endocarditis may result in significantly higher mortality in infected patients; therefore, these patients should be aggressively managed [36].

Figure 1. Effect of nonsystemic infections on survival of patients on continuous-flow left ventricular assist device support.

(A) LVAD-related infections (black line) or no LVAD infection (gray line). (B) Local non-LVAD-related infections (black line) or no local infection (gray line).

LVAD: Left ventricular assist device; VAD: Ventricular assist device.

Reproduced with permission from [14].

Prevention strategies

Numerous prevention strategies can be implemented to reduce the growing number of infections associated with LVADs at the preoperative, operative and postoperative stages. Success of LVAD implantation is largely dependent on appropriate patient selection, which is best performed by a multidisciplinary team of surgeons, cardiologists, nurses and dieticians [47]. Previously developed screening criteria and LVAD scoring systems may be particularly useful in this process [48]. In nonemergent cases, clinicians should consider to optimize modifiable risk factors for development infection, such as nutritional status, which might improve outcomes.

Prevention strategies in the perioperative period focus on a clean implantation technique that should be performed under operating-room conditions of limited traffic. To decrease the incidence of driveline infections, the driveline tunnel is made as long as possible. Once the lead has been tunneled in place, at least 1–2 cm of the lead’s velour covering should be left outside the exit site to allow for proper connection. The antibiotic prophylaxis regimen at our institution is generally consisted of vancomycin, a broad-spectrum cephalosporin, flucanazole, rifampin and nasal mupirocin on the night of surgery, followed by a 2-day course of vancomycin in combination with cephalosporin (either a first or fourth generation) and a 7-day course of nasal mupirocin. In the early post-implantation period, patients are followed in an intensive-care unit setting and should be closely monitored for signs and symptoms of device- and non-device-related infections. Since the majority of LVAD-related infections develop following initial hospital discharge, it is of utmost importance to provide standardized education regarding signs and symptoms of infection, and care of driveline, including sterile techniques for dressing changes.

Following hospital discharge, patients and/or their caregivers should strictly adhere to aseptic technique. Although there are no current clinical trials delineating the best regimen for the care of driveline infections, daily exit-site care with a persistent antiseptic cleansing agent is recommended. Use of topical antibiotics such as silver sulfadiazine or polymixin-neomycin-bacitracin are generally not recommended for prophylaxis due to the risk of tissue maceration and selecting for resistant microorganisms. The driveline should be secured to minimize the risk of trauma to the exit site. Driveline sites should be periodically assessed by physicians and nurses in clinical visits, along with routine assessment of nutritional status. Assessment by a nutritionist with appropriate supplementation may be indicated in patients with signs and symptoms of nutritional imbalance. In diabetic LVAD patients, hemoglobin A1c and blood glucose levels should be routinely monitored and appropriately managed to decrease infectious risk. Since LVAD patients are susceptible for infections, they should avoid situations that could place them at a greater risk (contact with sick individuals, poor hygiene and living conditions, and so on), and notify their healthcare team immediately with any signs or symptoms suspicious for infection.

Expert commentary

Heart transplantation remains the gold-standard therapy in patients with end-stage heart failure refractory to medical therapy, with excellent long-term survival rates. Unfortunately, this option is limited by the scarcity of available donors. After being proven as a successful therapy for bridge to transplantation, LVADs were shown to be superior to medical therapy in patients with advanced heart failure who are ineligible for cardiac transplantation, so-called ‘destination therapy’ according to the landmark REMATCH study [3]. This study demonstrated that LVAD could be used as a permanent therapy in thousands of individuals with advanced heart failure who are out of options. Despite superior outcomes that were demonstrated with these pulsatile pumps, this technology did not find widespread clinical application to the advanced heart failure population due to a high incidence of complications following implantation, particularly with respect to infection.

Second-generation continuous-flow LVADs were developed in an effort to overcome the limitations associated with the older-generation devices. These devices are smaller in size, require less surgical dissection, are easier to implant, and more durable compared with older generation devices. Indeed, prospective randomized comparison of HeartMate XVE (pulsatile) and HeartMate II (continuous) devices have proven that the HeartMate II device was associated with fewer incidences of device-related infections following implantation. The reduction in device-related infection rates could be due to the smaller size of the device and/or driveline and the differences in flow pattern; however, the precise mechanisms remain largely unknown. The CUBS trial suggested that a fully-implantable LVAD system that eliminated the need for a driveline was associated with lower rates of infection. Smaller third-generation LVADs are currently being evaluated in clinical trials, and preliminary results suggest a further reduction in infectious complications in patients with these pumps. Taken together, these findings suggest that device type and/or design appears to be a very important predictor of infectious complications irrespective of clinical risk factors.

In addition to the device design, appropriate patient selection for LVAD implantation remains a very important determinant of device-related infections. It is important to note that the majority of the current evidence in the literature (including the studies discussed in this article) is derived from studies of patients implanted with pulsatile-flow LVADs, which are largely replaced by continuous-flow LVADs and are mainly of historical importance at this time. Therefore, it is critical for each institution to collect clinical information on continuous-flow patients before and after LVAD implantation, and develop screening tools as well as scoring systems, to achieve better patient selection and superior outcomes. Multicenter patient registries such as INTERMACS could serve a great resource to identify risk factors for device-associated infection and develop prevention and management strategies in patients undergoing implantation of a new generation of devices.

Five-year view

With the recent approval of continuous-flow devices for destination therapy, the number of patients undergoing LVAD therapy will continue to increase exponentially over the next 5 years. Numerous third-generation devices are currently in preclinical and clinical trials and are expected to be in clinical use in the near future, which may in turn decrease the infection rates in these patients. Accumulation of more clinical data would allow for better understanding of clinical risk factors, prevention and management strategies of device-related infections. To date, genetic markers of susceptibility to device-related infection following LVAD implantation have not been investigated. Recent advances in next-generation sequencing and whole-genome single nucleotide polymorphism array technology might help us identify individuals at risk prior to device implantation, and may be implemented in decision-making to further improve outcomes.

Key issues.

Despite recent improvements in outcomes, device-related infections remain a significant complication of left ventricular assist device (LVAD) therapy.

Device-related infections can be categorized into driveline infection, pump-pocket infection and LVAD-associated endocarditis. Diagnosis is primarily made through clinical signs and symptoms, microbiological work-up and imaging modalities to assess for possible involvement of pump-pocket and extension into deeper tissues.

Appropriate patient selection is of utmost importance to prevent device-related infections. Modifiable risk factors such as nutritional status should be periodically assessed before and after LVAD implantation and modified accordingly. In addition to clinical risk factors, device-related risk factors such as device design, duration of support and trauma to the driveline exit site appear to be risk factor for device-related infections.

LVAD therapy induces defects in the cellular and humoral immune system, including selective reduction in the number of CD4+ T cells, defective proliferative responses of peripheral mononuclear cells, increased apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and B-cell hyper-reactivity as potential mechanisms of susceptibility to infection in these individuals.

Most common pathogens leading to device-related infection include Staphylococcus, Enterococcus and Pseudomonas species. Although rare, fungal species, particularly Candida, may lead to device-related infections

Patients with documented device-related infection should be aggressively treated with targeted antibiotic therapy and surgical intervention as indicated.

Further advances in genomic technology might help us identify individuals who are genetically at risk for developing device-related infections prior to implantation, and therefore allow for superior patient selection.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by research funds from the NIH (T32HL007081).

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics – 2011 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;123(4):e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stehlik J, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-seventh official adult heart transplant report – 2010. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(10):1089–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, et al. Long-term use of a left ventricular assist device for end-stage heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345(20):1435–1443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pagani FD, Miller LW, Russell SD, et al. Extended mechanical circulatory support with a continuous-flow rotary left ventricular assist device. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;54(4):312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, Milano CA, et al. Advanced heart failure treated with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361(23):2241–2251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oz MC, Gelijns AC, Miller L, et al. Left ventricular assist devices as permanent heart failure therapy: the price of progress. Ann. Surg. 2003;238(4):577–583. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000090447.73384.ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chinn R, Dembitsky W, Eaton L, et al. Multicenter experience: prevention and management of left ventricular assist device infections. ASAIO J. 2005;51(4):461–470. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000170620.65279.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holman WL, Rayburn BK, McGiffin DC, et al. Infection in ventricular assist devices: prevention and treatment. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2003;75(6 Suppl.):S48–S57. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00479-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Litzler PY, Manrique A, Etienne M, et al. Leukocyte SPECT/CT for detecting infection of left-ventricular-assist devices: preliminary results. J. Nucl. Med. 2010;51(7):1044–1048. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.070664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Topkara VK, Dang NC, Martens TP, et al. Bridging to transplantation with left ventricular assist devices: outcomes in patients aged 60 years and older. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005;130(3):881–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang R, Deng M, Rogers JG, et al. Effect of age on outcomes after left ventricular assist device placement. Transplant. Proc. 2006;38(5):1496–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.02.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan JA, Weinberg AD, Hollingsworth KW, Flannery MR, Oz MC, Naka Y. Effect of gender on bridging to transplantation and posttransplantation survival in patients with left ventricular assist devices. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2004;127(4):1193–1195. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dang NC, Topkara VK, Kim BT, Oz MC, Naka Y. Effect of race on outcomes in patients with left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) ASAIO J. 2004;50(2):148. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topkara VK, Kondareddy S, Malik F, et al. Infectious complications in patients with left ventricular assist device: etiology and outcomes in the continuous-flow era. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2010;90(4):1270–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaffer JM, Allen JG, Weiss ES, et al. Infectious complications after pulsatile-flow and continuous-flow left ventricular assist device implantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30(2):164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Topkara VK, Dang NC, Martens TP, et al. Effect of diabetes on short- and long-term outcomes after left ventricular assist device implantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24(12):2048–2053. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler J, Howser R, Portner PM, Pierson RN., 3rd Diabetes and outcomes after left ventricular assist device placement. J. Card. Fail. 2005;11(7):510–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uriel N, Naka Y, Colombo PC, et al. Improved diabetic control in advanced heart failure patients treated with left ventricular assist devices. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2011;13(2):195–199. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raymond AL, Kfoury AG, Bishop CJ, et al. Obesity and left ventricular assist device driveline exit site infection. ASAIO J. 2010;56(1):57–60. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3181c879b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butler J, Howser R, Portner PM, Pierson RN., 3rd Body mass index and outcomes after left ventricular assist device placement. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2005;79(1):66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin SI, Wellington L, Stevenson KB, et al. Effect of body mass index and device type on infection in left ventricular assist device support beyond 30 days. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2010;11(1):20–23. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.227801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holdy K, Dembitsky W, Eaton LL, et al. Nutrition assessment and management of left ventricular assist device patients. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24(10):1690–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimball PM, Flattery M, McDougan F, Kasirajan V. Cellular immunity impaired among patients on left ventricular assist device for 6 months. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2008;85(5):1656–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dang NC, Topkara VK, Kim BT, Lee BJ, Remoli R, Naka Y. Nutritional status in patients on left ventricular assist device support. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005;130(5):e3–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulman AR, Martens TP, Christos PJ, et al. Comparisons of infection complications between continuous flow and pulsatile flow left ventricular assist devices. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007;133(3):841–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milano CA, Naftel DC, Padera RF, et al. Infection during mechanical circulatory support: can we really expect a better outlook with continuous flow technology. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(2):S52. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aaronson KD, Slaughter MS, McGee E, et al. Evaluation of the HeartWare® HVAD Left Ventricular Assist Device System for the Treatment of Advanced Heart Failure: Results of the ADVANCE Bridge to Transplant Trial. Circulation. 2010;122:2215–2226. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zierer A, Melby SJ, Voeller RK, et al. Late-onset driveline infections: the Achilles’ heel of prolonged left ventricular assist device support. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007;84(2):515–520. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ankersmit HJ, Edwards NM, Schuster M, et al. Quantitative changes in T-cell populations after left ventricular assist device implantation: relationship to T-cell apoptosis and soluble CD95. Circulation. 1999;100(19 Suppl.):II211–II215. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.suppl_2.ii-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ankersmit HJ, Tugulea S, Spanier T, et al. Activation-induced T-cell death and immune dysfunction after implantation of left-ventricular assist device. Lancet. 1999;354(9178):550–555. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)10359-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimball PM, Flattery M, McDougan F, Kasirajan V. Cellular immunity impaired among patients on left ventricular assist device for 6 months. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2008;85(5):1656–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimball P, Flattery M, Kasirajan V. T-cell response to staphylococcal enterotoxin B is reduced among heart failure patients on ventricular device support. Transplant. Proc. 2006;38(10):3695–3696. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.10.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuster M, Kocher A, John R, et al. B-cell activation and allosensitization after left ventricular assist device implantation is due to T-cell activation and CD40 ligand expression. Hum. Immunol. 2002;63(3):211–220. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(01)00380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ankersmit HJ, Wieselthaler G, Moser B, et al. Transitory immunologic response after implantation of the DeBakey VAD continuous-axial-flow pump. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2002;123(3):557–561. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.120011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon D, Fischer S, Grossman A, et al. Left ventricular assist device-related infection: treatment and outcome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;40(8):1108–1115. doi: 10.1086/428728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monkowski DH, Axelrod P, Fekete T, Hollander T, Furukawa S, Samuel R. Infections associated with ventricular assist devices: epidemiology and effect on prognosis after transplantation. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2007;9(2):114–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2006.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nurozler F, Argenziano M, Oz MC, Naka Y. Fungal left ventricular assist device endocarditis. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2001;71(2):614–618. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01444-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baradarian S, Stahovich M, Krause S, Adamson R, Dembitsky W. Case series: clinical management of persistent mechanical assist device driveline drainage using vacuum-assisted closure therapy. ASAIO J. 2006;52(3):354–356. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000204760.48157.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garatti A, Giuseppe B, Russo CF, Marco O, Ettore V. Drive-line exit-site infection in a patient with axial-flow pump support: successful management using vacuum-assisted therapy. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26(9):956–959. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKellar SH, Allred BD, Marks JD, et al. Treatment of infected left ventricular assist device using antibiotic-impregnated beads. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1999;67(2):554–555. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)01243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tjan TD, Asfour B, Hammel D, Schmidt C, Scheld HH, Schmid C. Wound complications after left ventricular assist device implantation. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2000;70(2):538–541. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01348-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hutchinson OZ, Oz MC, Ascherman JA. The use of muscle flaps to treat left ventricular assist device infections. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001;107(2):364–373. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200102000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sajjadian A, Valerio IL, Acurturk O, et al. Omental transposition flap for salvage of ventricular assist devices. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006;118(4):919–926. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000232419.74219.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holman WL, Park SJ, Long JW, et al. Infection in permanent circulatory support: experience from the REMATCH trial. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23(12):1359–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sinha P, Chen JM, Flannery M, Scully BE, Oz MC, Edwards NM. Infections during left ventricular assist device support do not affect posttransplant outcomes. Circulation. 2000;102(19) Suppl. 3:III194–III199. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulman AR, Martens TP, Russo MJ, et al. Effect of left ventricular assist device infection on post-transplant outcomes. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28(3):237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams MR, Oz MC. Indications and patient selection for mechanical ventricular assistance. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2001;71(3 Suppl):S86–S91. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02627-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schaffer JM, Allen JG, Weiss ES, et al. Evaluation of risk indices in continuous-flow left ventricular assist device patients. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2009;88(6):1889–1896. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pae WE, Connell JM, Adelowo A, et al. Does total implantability reduce infection with the use of a left ventricular assist device? The LionHeart experience in Europe. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26(3):219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller LW, Pagani FD, Russell SD, et al. Use of a continuous-flow device in patients awaiting heart transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357(9):885–896. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holman WL, Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, et al. Infection after implantation of pulsatile mechanical circulatory support devices. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010;139(6):1632–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herrmann M, Weyand M, Greshake B, et al. Left ventricular assist device infection is associated with increased mortality but is not a contraindication to transplantation. Circulation. 1997;95(4):814–817. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gordon SM, Schmitt SK, Jacobs M, et al. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in patients with implantable left ventricular assist devices. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2001;72(3):725–730. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]