Abstract

Prior studies have demonstrated that events causing displacement from parents—such as parental death, abandonment of the adolescent, or divorce—represent a risk factor for adolescent suicide, but research to date has not established a theoretical model explaining the association between parental displacement and adolescent suicidal behavior. The current studies examined the construct of failed belonging proposed by the interpersonal theory of suicide as one factor that may link parental displacement with adolescent suicide. Study 1 found that low levels of belonging mediated the association between parental displacement and adolescent suicide attempts in a large urban community sample of older adolescents between the ages of 18 and 23. In Study 2, parental displacement interacted with low belonging to predict suicide attempts, such that adolescents (average age 16.6 years; (SD = 1.2) who experienced both displacement and low levels of belonging had the highest risk for suicide.

Suicide and suicidal behaviors represent a serious public health problem among adolescents. Overall, suicide ranks as the third leading cause of death among adolescents and young adults between the ages of 10 and 24, accounting for 12% of all recorded deaths in this age group in the United States in 2005 (CDC, 2008). There is also recent evidence that the problem of adolescent suicide may be increasing, as suicide rates among adolescents have been found to be increasing in recent years after a period of decline (Bridge, Greenhouse, Weldon, Campo, & Kelleher, 2008). In addition to death by suicide, suicide attempts and suicidal ideation among this age group also represent significant problems and have an even greater prevalence. A recent survey indicated that 6.9% of United States high school students reported a suicide attempt in the past year (CDC, 2008) and other recent studies have found lifetime rates of adolescent suicide attempts ranging from 1.3% to 10.1% (Bridge, Goldstein, & Brent, 2006).

These statistics highlight the importance of the problem of adolescent suicidal behavior, and research that can illuminate which individuals are at risk is crucial for developing effective prevention and treatment initiatives. A number of different psychiatric and psychosocial risk factors for adolescent suicidal behavior have been examined. A recent review of the literature on adolescent suicidal behavior indicated that psychiatric risk factors, including presence of a psychiatric diagnosis and past history of suicidal behavior, demonstrate the strongest association with suicidal behavior (Bridge, Goldstein, & Brent, 2006). However, a number of studies have found that psychosocial risk factors related to the interpersonal environment are also associated with suicidal behavior, even when controlling for their relationship with psychiatric risk factors such as clinical diagnoses (e.g., Esposito & Clum, 2003; Fergusson, Woodward, & Horwood, 2000; Gould, Fisher, Parides, Flory, & Shaffer, 1996; Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1996).

Life events causing displacement in the relationship between the adolescent and parent are one psychosocial risk factor for adolescent suicidal behavior that has emerged across a number of studies (Bridge et al., 2006). These displacement events lead to either actual separation from the parent or a profound disruption in the relationship between the adolescent and parent, and several different types of displacement events have been examined as risk factors for adolescent suicide. Experiencing the death of a parent has been associated with both adolescent death by suicide (Agerbo, Nordentoft & Mortenson, 2002) and suicide attempts (Lewinsohn et al, 1996). Separation from a living parent or change in a primary caretaker has also been associated with both death by suicide (Brent et al., 1994) and suicide attempts (DeWilde, Kienhorst, Diekstra, & Wolters, 1992; Fergusson et al., 2000). Similarly, spending time in foster care has been linked with increased likelihood of hospitalization for a suicide attempt (Vinnerljung, Hjern, & Lindblad, 2006), and a heightened risk of suicidal behavior has been observed even after adolescents are reunified with their parents (Taussig, Clyman, & Landsverk, 2001). Although it is not necessarily associated with a separation between the parent and adolescent, parental divorce is likely to cause a disruption in the relationship and has been found to be associated with both completed suicide (Gould et al., 1996) and suicide attempts (De Wilde et al, 1992). Overall, this accumulating evidence indicates that parental displacement is consistently associated with adolescent suicidal behaviors. However, studies have not described or tested a theoretical framework explaining why displacement leads to suicidal behavior.

The interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior (Joiner, 2005) is a recent theoretical development that may offer an explanation for the association between parental displacement and adolescent suicidal behavior. The interpersonal theory proposes that suicidal behavior is a result of individuals having both the desire for death and the ability to enact serious self-injury. The theory proposes that the desire for death is caused by two failed interpersonal processes, a thwarted sense of belonging resulting from an unmet need to belong (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), and a sense of burdensomeness resulting from feeling that one is a burden on close others (Joiner et al., 2002). Additionally, individuals must acquire the ability to enact lethal self-injury, which is acquired through exposure to painful and provocative experiences that enable individuals to habituate to the fear and pain necessary to engage in suicidal behavior. The interpersonal theory has received strong support to date in over twenty empirical studies with adults which indicate that low belonging, burdensomeness, and acquired ability are associated with suicidal behaviors (see Van Orden et al., 2010, for a review).

While the interpersonal theory has not specifically been tested in adolescents to date, the processes involved in the theory have been proposed to be universal across the lifespan (Joiner, 2005), and research on suicidal behavior in children and adolescents suggests that the key constructs specified by the theory are applicable to younger age groups. For example, research on the “expendable child” provides evidence that burdensomeness is associated with suicidality in adolescents. A study of suicidal adolescents found that adolescents who reported suicidal ideation and behavior scored higher on a measure of expendability, which included specific items related to a sense of being a burden on one’s family (Woznica & Shapiro, 1990). Increased acquired ability, as indicated by a lack of pain response during self-injury, has been found to be predictive of number of lifetime suicide attempts in adolescents (Nock, Joiner, Gordon, Lloyd-Richardson, & Prinstein, 2006). The processes involved in the acquired ability for self-injury and suicidal behavior have even been observed in children as young as five, as a study of preschool children hospitalized for suicidal behavior found that these children had higher pain tolerance than a control group of children hospitalized for behavioral problems (Rosenthal & Rosenthal, 1984).

The construct of failed belonging proposed by the interpersonal theory of suicidal behavior is most relevant to the discussion of parental displacement and adolescent suicidal behavior, as it is likely that parental displacement events would have a significant impact on adolescent belonging. The definition of failed belonging in the interpersonal theory is based on the work of Baumeister and Leary (2005), who argue that all individuals have a fundamental need to belong that is only met if one has frequent, positive interactions with others and feels cared about by significant others. Recent theoretical elaboration by Van Orden and colleagues (2010) further clarifies this definition by defining two separate but related facets of thwarted belonging that have been empirically associated with suicidal behavior: the experience of loneliness and a lack of stable, caring relationships. Again, although direct tests of the interpersonal theory in adolescents have not been conducted, research on psychosocial risk factors for suicide in adolescents has begun to establish an association between both of these facets of failed belonging and suicidal behavior. For example, a survey of middle-school students found that feelings of loneliness were significantly associated with suicidal ideation (Roberts, Roberts, & Chen, 1998). Similarly, a study of adolescent psychiatric inpatients found that both peer rejection and low quality of peer relationships were associated with more severe suicidal ideation (Prinstein, Boergers, Spirito, Little, & Grapentine, 2000).

Parental relationships may represent one important source of belonging for adolescents, as parents may be particularly important for providing the stable, caring relationships that are a central component of belonging. Consistent with this possibility, there is some evidence that positive relationships between parents and adolescents are a protective factor that reduces risk of suicidal behavior in adolescents. Data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health found that connectedness with parents, including closeness with parents and the perceived caring of parents, was associated with lower levels of past suicidal ideation and attempts (Resnick et al, 1997) as well as serving as a protective factor against suicide attempts in the subsequent year (Borowsky, Ireland, & Resnick, 2001). Higher levels of parental involvement with children have been found to be a protective factor against adolescent suicide attempts (Flouri & Buchanan, 2001). Similarly, a recent treatment study of adolescents who had a prior suicide attempt found that family cohesion was protective against future attempts (Brent et al, 2009).

These studies provide preliminary evidence that parental relationships may be related to belonging for adolescents, and it seems probable that displacement events that disrupt the parent-adolescent relationship would negatively impact the adolescent’s sense of belonging by diminishing both the frequency and quality of interactions between the parent and adolescent. Again, while no studies to date have directly tested the link between displacement events and adolescent belonging, one study provides support for this hypothesis. A study of comparing Korean adolescents from immigrant families to Korean adolescents who had separated from one or both parents to move to the United States for schooling found that the adolescents who had separated from their families reported experiencing lower levels of parental support and higher levels of suicidal ideation than adolescents from intact immigrant families (Cho & Hasalm, 2010).

Taken together, these studies suggest that parental displacement may be associated with the construct of failed belonging from the interpersonal theory of suicide, and this association with failed belonging could account for the observed increase in suicide risk that has been found in displaced adolescents in prior studies. The current studies provide a direct test of this proposed association between parental displacement, low belonging, and adolescent suicidal behavior in two large, population-based samples of adolescents. We hypothesized that parental displacement events would lead to lower levels of belonging in adolescents by decreasing both the quality and quantity of interactions between the adolescent and parents. Specifically, we hypothesized that this experience of displacement would be associated with the experience of a decreased sense of belonging for the adolescent, manifested by phenomena such as increased sense of loneliness and a decreased sense of social support. We predicted that this failed belonging would have a direct effect on adolescent suicidal behavior, and therefore we expected to find a mediational relationship in which failed belonging mediated the observed relationship between parental displacement and adolescent suicidal behavior.

Study 1

Method

Participants

The current study included 1175 participants (541 men, 634 women) from a representative, urban community sample of older adolescents between the ages of 18 and 23. These participants were interviewed in 2002 as part of a multi-wave population based study conducted in south Florida. This study built on a previous population based investigation based in the Miami-Dade public school system (Vega & Gil, 1998; Turner & Gil, 2002). Importantly, this sample was ethnically diverse, consisting of approximately 28% non-Hispanic white participants, 46% Hispanic participants, and 26% African American participants. All participants completed either a face-to-face interview (70%) or a phone interview (30%), during which they answered questions regarding demographics, psychosocial variables, and mental health symptoms, including previous suicidal behavior. Data collection was approved by the Florida State University institutional review board, and all participants completed informed consent for participation in the study.

Measures

Recent suicide attempt

All participants were asked to report if they had engaged in a suicide attempt within the last year. Participants were rated (0) if they reported no attempts within the last year, and (1) if they reported an attempt within the last year.

Low social support (low belonging)

Participants’ perceptions of belonging were assessed using a measure of social support. Social support provides a good measure of belonging in this sample because it assesses participants’ perceptions that they have frequent, stable, and positive sources of interaction with family and friends, which are key aspects of belonging. Our measure of social support was created by assessing each participant’s combined levels of family social support and friendship support using the Provision of Social Relations Scale (Turner, Frankel, & Levin, 1983). The measure included 22 items. Most items measured positive aspects of support, such as feeling loved and cared for (i.e., “You feel that your family really cares about you”), closeness (i.e., “You feel close to your family”), acceptance (i.e., “When you are with your friends you are able to completely relax and be yourself”), and feeling able to rely on others (i.e., “Your family would always take the time to talk over your problems, should you want to”). Five of the items measured negative support such as criticism (i.e., “Your family is always telling you what to do and how to act”). These questions were rated with a five-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree, 5=strongly disagree), so that higher scores on the measure indicate lower levels of belonging. The alpha for the low social support scale in the present sample was .89, indicating good levels of internal consistency for the measure.

Parental displacement

All participants answered questions regarding parental displacement as part of a survey of stressful life events. For the current study, due to the older age of participants, only events occurring in the late adolescent period, after the age of 15, were included. Events were classified as parental displacement events if they involved a physical separation between the adolescent and parent or caused a disruption in the relationship between the adolescent and parent. Parental displacement events in the current study included the following scenarios: being sent away from home as a punishment, being abandoned by parents, living in an orphanage/foster home, being forced to live apart from parent(s), and parents becoming separated/divorced. Each participant was asked if he or she had ever experienced these situations, and each scenario was rated with (1) for each experience endorsed, and (0) if the participant had not experienced that situation. Each of these experiences was then summed to create a variable of overall level of displacement in late adolescence. Examination of the skewness and kurtosis of this variable indicated that it was normally distributed.

Data Analysis

The goal of Study 1 was to examine whether parental displacement contributed to suicide attempts through its association with low belonging. To explore this hypothesis, we used a path analysis model in which parent displacement was the source variable, which led to feelings of low social support as the mediator variable, which finally led to report of a suicide attempt as a dichotomous outcome variable (coded a 0=no attempt, 1=attempt). In this model we also included participant age, gender, and socio-economic status as covariates. Analyses were conducted using the MPlus statistical modeling software (Version 5.1; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2008). Standard model fit-evaluation criteria were used a CFI value greater than .95 and a RMSEA value less than .08 indicating good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Because this model involved a dichotomous outcome variable, the WLSMV estimator and theta parameterization were used in MPlus; these specifications are specifically designed for handling non-continuous outcome variables.

Results

First, we explored the correlations between parental displacement, social support and suicide attempt status. The means, standard deviations, and correlations for these variables can be found in Table 1. In the present sample 19 individuals (approximately 1.1% of participants) reported having attempted suicide within the last year. As predicted by the interpersonal theory of suicide, there was a significant bivariate correlation between a recent suicide attempt and low social support (r=.12, p<.01). Results for parental displacement were also in line with the theory’s predictions, as parental displacement had significant bivariate correlations with both suicide attempt status (r=.08, p<.01), and low social support (r=.21, p<.01).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for Study 1 Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Displacement | -- | ||

| Social Support | .21* | -- | |

| Attempt Status | .08* | .12* | -- |

|

| |||

| Mean | 41.46 | .21 | .01 |

| Standard Deviation | 11.60 | .50 | .10 |

Note:

indicates significant at p<.05

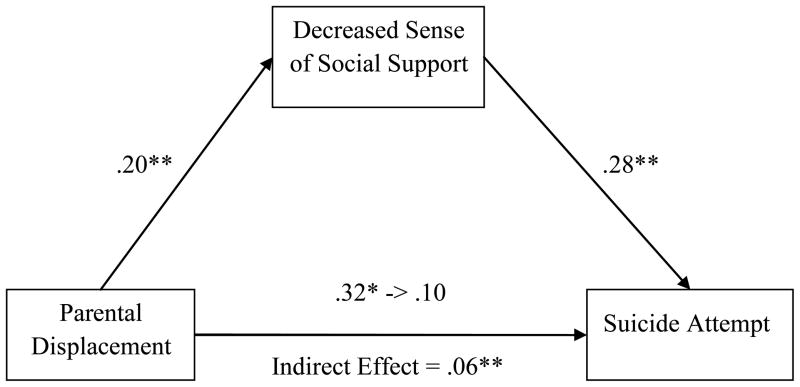

To examine our hypothesis that parental displacement would be associated with adolescent suicidality through its relationship with low social support, we predicted that a mediational model would best describe the relationships between the three variables. Thus, a mediational model was examined in a path analysis with the source variable being displacement, the mediator being social support, and the outcome variable being a recent suicide attempt. Participant age, gender, and socio-economic status were included as model covariates. The path magnitudes obtained for this model are displayed in Figure 1. This model provided a good fit to the data (CFI>.99, RMSEA<.001). In this model, the first path, between parental displacement and low social support was significant (β=.20, p<.001). As predicted, the path between the mediator and outcome variable, suicide attempt, was also significant (β=.28, p<.001). Importantly, when controlling for the mediator variable, low social support, the previous significant relationship (β=.32, p<.01) between parental displacement and suicide attempt became non-significant (β=.10, p=.06). Mediation was further supported by a significant indirect effect of parental displacement on suicide attempt (β=.06, p<.01), obtained through MPlus. The only covariate in the model to significantly predict suicide attempt was age (β= −.18, p=.03), and SES was also a significant predictor of low social support (β= −.25, p<.001).

Figure 1. Relationship Between Displacement, Social Support, and Suicide Attempt Status.

*Indicates path significance at the p < .05 level; ** Indicates path significance at the p < .01 level.

The final test of our mediational model was to further test the flow of the mediational effects of low social support on the relationship between parental displacement and suicide attempt. The PRODCLIN program was used to test the mediational impact of both mediation variables used. This program was developed by MacKinnon and colleagues (2007) and tests mediational effects without some of the problems inherent in other methods of testing for mediation (e.g. inflated rates of Type I error, see MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). In addition, the logic for this method is suited to testing for mediation in path analysis (Bollen, 1987). PRODCLIN examines the product of the unstandardized path coefficients divided by the pooled standard error of the path coefficients (αβ/σαβ) and a confidence interval is generated. If the values between the upper and lower confidence limits include zero, this suggests the absence of a statistically significant mediation effect. The unstandardized path coefficients and standard errors of the path coefficients for the indirect effect of parental displacement and suicide attempts via low social support were entered into PRODCLIN to yield lower and upper 95% confidence limits of .06 and .18. These findings further support the mediational impact of low belonging and low social support on the relationship between parental displacement and suicide attempts.

Discussion

Results of Study 1 are consistent with past work which has found an association between parental displacement and adolescent suicidality, but extend that work by placing the association within the context of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Events causing displacement between the adolescent and parent were found in the present study to be associated with suicide attempts, but the association between parental displacement and adolescent suicide was fully accounted for by the relationship between parental displacement and the adolescent’s report of feelings of low belonging as measured by an index of social support. These results suggest that parental displacement events may disrupt the adolescent’s interpersonal environment, leading to decreased feelings of belonging and an increased desire for death as proposed by the theory.

The present study had several features which limit the interpretation of results. Most notably, the study was cross-sectional in nature, and thus it is difficult to determine the temporal pattern of the association between the variables. In most cases, the data indicated that displacement events preceded suicide attempts, as all reported suicide attempts occurred within the past year but displacement events occurred in the preceding few years, after age 15. However, it is uncertain whether low levels of belonging preceded or were the result of parental displacement events. For this reason, future studies are needed to determine temporal precedence in this association. Another potential limitation of the study was the older age of participants at the time of the assessment. While the parental displacement events occurred during the period of late adolescence, some participants were already in the young adult period at the time of assessment. It is notable that these parental displacement events continued to have an impact on suicide attempts extending into the period of emerging adulthood, but due to the age of participants the applicability of these results to the adolescent period may be limited. Study 2 addressed this limitation by examining a sample of younger adolescents.

Study 2

Method

Participants

Data for this study were drawn from the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (Lewinsohn, Hops, Rohde, Seeley, & Andrews, 1993). Participants were adolescents who were randomly selected from 9 high schools in urban and rural Oregon who completed a large battery of assessment measures including a semistructured diagnostic interview as well as self-report indices of symptoms and psychosocial variables. A total of 1,709 participants completed the Time 1 (T1) assessment–representing an overall participation rate of 61%. Participants’ average age at T1 was 16.6 years (SD = 1.2), and 59% of the sample were girls. For more detailed information about the sample and its representativeness of the population, which was considerable, see Lewinsohn et al. (1993). In the current study, due to some participants missing survey data on some of the variables included in the analyses, the total sample size was 1,482 participants.

Measures

Loneliness (low belonging)

Belonging was assessed using a measure of loneliness. While loneliness does not capture the total construct of belonging, as it does not directly measure the experience of connectedness and positive interactions with others, recent theoretical work has described loneliness as one of the two primary facets of the experience of failed belonging (Van Orden et al., 2010). For this reason, we view loneliness as reflecting a key component of the subjective experience of failed belonging, and feel that it represents an adequate measure for testing the association between failed belonging and suicidal behavior in the current study. For the current study, we assessed loneliness using the adapted UCLA Loneliness Scale (Roberts, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1993). This scale is a brief, eight-item measure adapted from the original twenty item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, Peplau, & Cutrona, 1980). Items were selected for the adapted scale based on past work with the scale, their perceived face-validity with adolescents, and discussion with a focus group of adolescents. Items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often) and included statements such as “I feel isolated from others” and “I lack companionship.”

Parental displacement

An index of parental displacement was calculated using participants’ responses to selected items of a self-report measure of negative life events that occurred in the past year. Items were drawn from the Schedule of Recent Experiences (Holmes & Rahe, 1967) and the Life Events Schedule (Sandler & Block, 1979). As in study 1, events were classified as parental displacement events if they involved a physical separation between the adolescent and parent or were likely to cause a significant disruption in the relationship between the adolescent and parent. The following events were coded as parental displacement events: divorce of parents, arrest of a parent, death of a parent, extended illness or severe injury of a parent, and abandonment by a parent. While arrest, illness, and injury of a parent may not be typically viewed as displacement events, we feel that, like divorce, they represent significant displacement events because they likely involve either a temporary separation from the parent or would decrease the quantity of quality of interactions between the adolescent and the parent. Again, each of these scenarios was coded (1) if the participant had experienced that situation and (0) if he or she had not experienced it. The ratings for each scenario were summed to create a continuous measure of parental displacement. Examination of the skewness and kurtosis of this variables indicated that it was normally distributed.

Suicidal behavior

Suicidal behavior was assessed during the diagnostic interview administered to all participants, and participants were asked if they had ever attempted death by suicide. If they responded affirmatively, they were asked to identify how many times they had attempted suicide in the past. For the present study, these responses were used as a count variable of number of suicide attempts.

Data Analyses

In order to examine the relationships between displacement and suicidal behaviors, we used zero-inflated Poisson regression (ZIP). This analytic approach accounts for the fact that number of previous suicide attempts is a count variable, and is thus non-normally distributed. Furthermore, a variable like previous number of suicide attempts is likely to contain a large portion of individuals who have never attempted suicide, resulting in an inflated response of zero. ZIP takes the inflated zero response into account by dividing the analysis of the suicide count variable into two components: 1) the occurrence of a suicide attempt, and 2) the frequency of previous suicide attempts for those who have attempted. Independent variables are then tested to determine if they significantly predict either portion of the count variable. The MPlus statistical modeling program was used to conduct these analyses. The occurrence portion of the suicide variable was interpreted as a dichotomous variable (previous suicide attempt =0, no attempt =1) with a binomial distribution and a logit link, while the frequency portion of the suicidal behavior variable is estimated as a count variable with a Poisson distribution and log link.

Our goal was to replicate the analyses of Study 1 and examine the association between parental displacement, failed belonging, and suicidal behavior. A mediational model was again tested to determine whether the association between parental displacement and suicidal behavior was mediated by low levels of belonging. Gender was used as a covariate in this model, but age was not due to the restricted range of participants in this study (16 and 17 year-olds).

Results

The means, standard deviations, and correlations between variables used in Study 2 are presented in Table 2. In this sample 26 individuals reported attempting suicide at least one time (approximately 1.5% of the sample). There was a small, yet significant, correlation between parental displacement and loneliness (r = .06, p<.01). Displacement and loneliness did not have significant correlations with the number of previous suicide attempts reported, which may have been a function of the count nature of the variable. Thus, we explored mediational analysis using ZIP regression.

Table 2.

Means, Correlations, and Standard Deviations for Study 2 Variables

Note:

indicates significance at p<.05

indicates percentage of sample endorsing at least one suicide attempt; UCLA = UCLA Loneliness Scale, DISPL = Parental Displacement

SA = Number of Suicide Attempts

The analyses exploring loneliness as a mediator of the relationship between parental displacement and suicidal behavior were conducted by including both variables in a model as predictors of both the occurrence and frequency of previous suicide attempts. A path linking parental displacement as a predictor of loneliness was also modeled, allowing for the exploration of a mediational path. The results of the analysis indicated that displacement was a significant predictor of loneliness (β = .06, p=.02). Consistent with the interpersonal theory, loneliness was a significant predictor of the occurrence of a previous suicide attempt (β= −.35, p<.01, OR=.85). However, contrary to our hypotheses, parental displacement alone did not predict the occurrence of a previous suicide attempt. Additionally, neither loneliness nor displacement represented significant predictors of frequency of previous suicide attempts.

One possible reason that we failed to find an association between loneliness, displacement, and suicidal behavior would be if the experience of displacement did not lead to the experience of failed belonging in all of our participants. Recent theoretical work by Van Orden and colleagues (2010) has suggested that failed belonging is a dynamic state that may depend on the interaction between life events and intrapersonal factors. In this case, it is possible that while parental displacement would not be sufficient to lead to failed belonging in all adolescents, those adolescents who are already cognitively vulnerable to low belonging due to the experience of loneliness may respond to a displacement event by experiencing thwarted belonging and subsequent risk for suicidal behavior. To test this possibility, an exploratory analysis examining a moderational model of the association between loneliness, parental displacement, and suicide was conducted to determine whether parental displacement and loneliness have an interactive effect in predicting suicidal behavior..

To test this potential interaction we included displacement, loneliness, and the two-way interaction of these variables in the model simultaneously predicting both occurrence and frequency of suicidal behavior. Similar to the mediational analysis, results indicated significant main effect for loneliness (β= −.35, p<.01,, OR=.85) but not displacement (β= −.035, p=.80,OR=.02) predicting the occurrence of a suicide attempt, but not the frequency of suicide attempts. These results were qualified, however, by a significant interaction effect in predicting the occurrence of a previous suicide attempt (β= .13, p<.01, OR=1.30). Results predicting the frequency of previous suicide attempts showed that the interaction was not significant (β= .31, p=.70). Participant sex was not a significant predictor of either occurrence or number of suicide attempts.

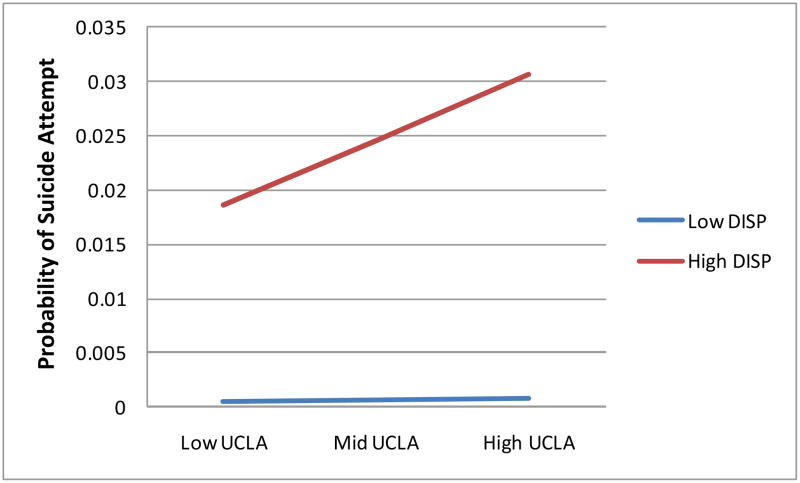

The nature of the interaction between loneliness and parental displacement in predicting the occurrence of a suicide attempt can be seen in Figure 2. It is important to note that this interaction has been graphed in reverse for ease of interpretation; this is because ZIP assesses the non-occurrence of a count variable, so the values obtained refer to a higher probability that no suicide attempts were endorsed but are graphed in regard to probability of a suicide attempt being reported. As can be seen in Figure 2, those with low levels of displacement had minimal probability of a suicide attempt. For those with high displacement, however, even for high levels of belonging there was an increased probability of a previous suicide attempt. Furthermore, for those with high displacement and low belonging there was a much increased probability of the occurrence of a suicide attempt.1

Figure 2. Interaction Between Loneliness and Displacement in Predicting Suicide Attempt.

Low and high levels are 1 standard deviation above/below the mean. UCLA refers to the UCLA depression scale; DISP refers to the Displacement composite variable.

Discussion

Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, it is somewhat unclear why the combination of displacement and low belonging would be especially pernicious for adolescents in this sample. One plausible possibility is that displacement may serve to activate or amplify preexisting feelings of failed belonging, leading to an increased desire for death and thus an increased probability of a suicide attempt. In this way, failed belonging may be viewed as a potential diathesis for suicidal behavior that may be activated by certain interpersonal life stressors. Alternatively, it may be that parental displacement events are associated with decreases in belonging for a certain subset of individuals, such as those with a depressogenic cognitive style or preexisting suicidal ideation. Similar to Study 1, the current study is limited by its cross-sectional design, and thus the temporal relationship between these variables is unclear.

General Discussion

Consistent with prior research demonstrating an association between parental displacement events and adolescent suicidality, the current studies demonstrated that parental displacement was associated with suicide attempts in two large, population based samples of adolescents. Results of the present studies extend prior work, however, by demonstrating that the effect of displacement on suicidality can be more clearly interpreted in light of the association between parental displacement and the broader interpersonal variable of thwarted belonging proposed by Joiner’s (2005) interpersonal theory of suicide. The theory proposes that thwarted belonging is associated with an increased desire for death and thus increased risk for suicide, and both of the present studies indicated that parental displacement in conjunction with failed belonging was associated with adolescent suicide attempts. The nature of that association, however, differed somewhat between the two studies.

Results of Study 1 were consistent with our initial hypothesis that parental displacement would be associated with suicide attempts through its association with low belonging as measured by an index of social support. This hypothesis was supported by the results of a mediational model which indicated that the association between displacement and suicide attempts was fully mediated by the association between displacement and low levels of belonging. Overall, these results suggest that parental displacement events are associated with disruptions of the adolescent’s interpersonal environment, which are, in turn, associated with increased risk for a suicide attempt.

In contrast, the pattern of results found in Study 2 was more complex. A mediational model was not supported in this sample. Instead, a moderational model best fit the data, with a significant interaction found between parental displacement and failed belonging as measured by an index of loneliness. This pattern of results indicated that, while all adolescents who experienced displacement had an increased risk of a suicide attempt, those who experienced both displacement and low levels of belonging had the greatest risk for suicide attempts. This pattern of results suggests that displacement may serve to amplify the effects of failed belonging, increasing or activating the desire for death in vulnerable adolescents.

While both studies showed effects for parental displacement on suicide attempts as a function of low levels of belonging, the difference between the two samples is noteworthy. One possible explanation for this difference may lie in the different indices of belonging used in the two studies. While both the measures of social support and loneliness are directly related to the construct of belonging proposed by Joiner’s (2005) theory, they appear to tap into distinct facets of the construct that have slightly different associations with interpersonal events such as displacement and thus affect suicidality in different ways.

For Study 1, the index of belonging was a measure of social support that assessed the adolescent’s feelings of belonging in the context of specific relationships with family members and friends. In this way, participants were forced to focus on specific relationships when reporting their feelings of belonging. Those participants who experienced parental displacement would likely have also reported deficits in social support related to their relationships with their parents, and thus our measures of parental displacement and belonging may have been more closely related. In contrast, the measure of belonging in Study 2 was a much more general measure of feelings of loneliness. Loneliness as it was assessed in this study represents a broader, more cognitive facet of the construct of belonging than the specific measure of social support in relationships used in Study 1. Thus, instead of measuring belonging as it is directly related to the interpersonal environment as in Study 1, the measure of loneliness may be viewed as a broader, more stable cognitive risk factor for suicidal behavior, accounting for its interactive effect with parental displacement on suicide attempts. Future research can better describe these different facets of belonging and determine whether they have distinct associations with suicidal behavior.

While both studies found significant associations between displacement, belonging, and suicidal behavior, it is important to note that the size of the observed effects was small. This is consistent with past research indicating that the strongest risk factors for suicidal behavior are psychiatric risk factors such as diagnosis or past attempts, while psychosocial risk factors have small effects on predicting risk (Bridge et al, 2006). Despite the small size of the effects, however, they are significant because they fit into a predictive model of suicidal behavior and they provide a theoretical rationale for the observed association between displacement and suicidal behavior. For this reason, even though the independent effects of displacement or belonging on predicting suicide attempts is small, they play a role in our overall understanding of the interpersonal context of suicidal behavior as well as helping refine our ability to predict suicidal behavior in the context of a theoretical model. Additionally, since suicidal behavior is such a serious public health problem, any variables that can reliably predict suicide attempts are important to consider. Finally, these results provide one of the first tests of the interpersonal theory of suicide in adolescents, and indicate that the theory can be successfully applied to adolescents.

Although the current studies provide evidence that the parental displacement is associated with adolescent suicidality in conjunction with its relationship to failed belonging, they are limited by the cross-sectional nature of their design. The present studies were unable to determine temporal associations between thwarted belonging and parental displacement. While it seems plausible that parental displacement would decrease feelings of belonging, which would account for the mediational model found in Study 1, longitudinal studies are needed to establish a causal relationship. Similarly, longitudinal research is needed to determine the temporal pattern of the interaction observed in Study 2 and establish whether low levels of belonging act as a risk factor for adolescents who experience displacement or whether certain adolescents respond to displacement events with decreases in feelings of belonging.

Another limitation of the current studies is their limited application of the theoretical context of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Both studies established that parental displacement is associated with the construct of low belonging as proposed by the interpersonal theory, but they did not address the two other components of the theory, perceived burdensomeness and the acquired ability to enact lethal self-injury. Although the construct of failed belonging seems most intuitively related to parental displacement, it is also plausible that displacement could impact the other variables, and that these variables may also partially account for the association between adolescent suicidality and displacement. For example, it is possible that adolescents who experience displacement may develop the belief that they area burden on their families. Additionally, displaced adolescents may lack the parental supervision that prevents them from engaging in painful and provocative experiences, and thus may be more likely to increase their acquired ability for suicide. While the observed association between displacement and failed belonging provides a new theoretical basis for understanding the association between displacement and adolescent suicidality, further research is also needed to examine the other aspects of the theory and their potential relationship to displacement

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Despite these limitations, the present studies provide important evidence for developing a theoretical model for explaining the previously established association between parental displacement and adolescent suicidality. In two large, diverse, population-based samples of adolescents, parental displacement was found to be a correlate of suicide attempts in conjunction with low belonging. These results are one of the first tests of the interpersonal theory of suicide in adolescents, and suggest that further work extending the major predictions of the theory to studying suicidal behavior in adolescents would provide a fruitful line of inquiry. In particular, longitudinal research to establish the temporal nature of the associations would be beneficial. Results also may have important implications for clinical work, and suggest that failed belonging may be one factor to consider in working with adolescents who experience parental displacement events. For displaced adolescents who already experience suicidal ideation or suicidal behavior, low feelings of belonging may also represent an important treatment target in psychotherapy. Interventions focused on increasing belonging by supporting family relationships, strengthening positive peer relationships or fostering relationships with mentors or other adults may be beneficial for decreasing adolescent suicide risk. Alternatively, targeted preventive interventions with displaced adolescents could work to decrease suicide risk by fostering belonging, perhaps especially with those adolescents who already report loneliness.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded, in part, by National Institute of Mental Health grant F31MH081396 to Edward A. Selby, under the sponsorship of Thomas E. Joiner, Jr. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. We also thank R. Jay Turner for the allowing the use of his data for this study.

Footnotes

To follow-up on the significant interaction found in Study 2, the interaction between displacement and belonging was also examined in the sample from Study 1. While a significant interaction effect was obtained, the form of the interaction was complex and not fully consistent with results from Study 2. Results suggested all adolescents who experienced displacement showed higher probability of a suicide attempt regardless of levels of belonging, but low levels of belonging conferred a risk for suicide attempt in adolescents who did not experience displacement events.

References

- Agerbo E, Nordentoft M, Mortenson PB. Familial, psychiatric, and socioeconomic risk factors for suicide in young people: Nested case control study. British Medical Journal. 2002;325:74–77. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7355.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Greenhill LL, Compton S, Emslie G, Wells K, Walkup JT, Turner JB. The Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters study (TASA): Predictors of suicidal events in an open treatment trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:987–996. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbe4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Liotus L, Schweers J, Balach L, Roth C. Familial risk factors for adolescent suicide: A case-control study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1994;89:52–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:372–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Weldon AH, Campo JV, Kelleher KJ. Suicide trends among youths aged 10–19 years in the United States, 1996–2005. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300:1025–1026. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.9.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Total, direct, and indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1987;17:37–69. [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky IW, Ireland M, Resnick MD. Adolescent suicide attempts: Risks and protectors. Pediatrics. 2001;107:485–493. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2007. Surveillance Summaries, June 6, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(SS-4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y, Haslam N. Suicidal ideation and distress among immigrant adolescents: The role of acculturation, life stress, and social support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:370–379. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9415-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWilde EJ, Kienhorst ICWM, Diekstra RFW, Wolters WHG. The relationship between adolescent suicidal behavior and life events in childhood and adolescence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:45–51. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito CL, Clum GA. The relative contribution of diagnostic and psychosocial factors in the prediction of adolescent suicidal ideation. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:386–395. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Risk factors and life processes associated with the onset of suicidal behavior during adolescence and early adulthood. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:23–39. doi: 10.1017/s003329179900135x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flouri E, Buchanan A. The protective role of parental involvement in adolescent suicide. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention. 2001;23:17–22. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.23.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Fisher P, Parides M, Flory M, Shaffer D. Psychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicide. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1155–1162. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120095016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Pettit JW, Walker RL, Voelz ZR, Cruz J, Rudd MD, Lester D. Perceived burdensomeness and suicidality: Two studies on the suicide notes of those attempting and those completing suicide. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2002;21:531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA. Adolescent psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:133–44. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1996;3:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39(3):384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Author; 1998–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Joiner TE, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research. 2006;144:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein M, Boergrs J, Spirito A, Little T, Grapentine WL. Peer functioning, family dysfunction and psychological symptoms in a risk factor model for adolescent inpatients’ suicidal ideation severity. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29(3):392–405. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2903_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, Tabor J, Beuhring T, Sieving RE, Shew M, Ireland M, Bearinger L, Udry R. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen YR. Suicidal thinking among adolescents with a history of attempted suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1294–300. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. A brief measure of loneliness suitable for use with adolescents. Psychological Reports. 1993;72:1379–1391. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3c.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal PA, Rosenthal S. Suicidal behavior by pre-school children. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;141:520–525. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39:472–480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Block M. Life stress and maladaptation of children. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1979;8:41–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00894384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taussig HN, Clyman RB, Landsverk J. Children who return home from foster care: A 6-year prospective study of behavioral health outcomes in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):e10. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Frankel BG, Levin DM. Social support: Conceptualization, measurement, and implications for mental health. In: Greenley J, editor. Community and Mental Health. Vol. 3. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1983. pp. 67–110. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Gil A. Psychiatric and substance use disorders in South Florida: Racial/ethnic and gender contrasts in a young adult cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:43–50. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gil AG. Longitudinal research in the social and behavior sciences: An interdisciplinary series. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. Drug use and ethnicity in early adolescence. [Google Scholar]

- Vinnerljung B, Hjern A, Lindblad F. Suicide attempts and severe psychiatric morbidity among former child welfare clients – a national cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(7):723–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woznica JG, Shapiro JR. An analysis of adolescent suicide attempts: The expendable child. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1990;15:789–796. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/15.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]