Abstract

Context:

In epidemiological studies of childhood obesity, simple and reliable surrogate estimates of insulin sensitivity are needed because the gold standard, the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, is not feasible on a large scale.

Objective:

To examine the correlation of fasting and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)-derived surrogate indices of insulin sensitivity with the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp in obese adolescents with normal glucose tolerance, prediabetes, and diabetes.

Patients and Design:

A total of 188 overweight/obese adolescents (10 to <20 yr old) who completed a standard 2-h OGTT and 3-h hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp were included. Fasting-derived surrogates [fasting glucose (GF), fasting insulin (IF), 1/IF, GF/IF, homeostasis model assessment and quantitative insulin sensitivity check index] and OGTT-derived surrogates [whole-body insulin sensitivity index and the ratio of glucose and insulin areas under the curve (GlucAUC/InsAUC)] were calculated.

Main Outcome Measures:

We evaluated the correlations between the clamp-measured insulin sensitivity and the surrogate estimates and area under the receiver operating characteristic curves.

Results:

Fasting indices (1/IF, GF/IF, homeostasis model assessment of insulin sensitivity, and quantitative insulin sensitivity check index) correlated significantly with clamp insulin sensitivity (r = 0.82, 0.78, 0.81, and 0.80, respectively), with lower correlations between the OGTT surrogates and clamp (whole-body insulin sensitivity index, r = 0.77; GlucAUC/InsAUC, r = 0.62). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curves was more than or equal to 0.94 for all surrogates except GlucAUC/InsAUC. Across quartiles of clamp-measured insulin sensitivity, there was a significant overlap in individual values of IF, 1/IF, and GF/IF.

Conclusion:

In obese adolescents with normal or impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes, OGTT-derived surrogates do not offer any advantage over the simpler fasting indices, which correlate strongly with clamp insulin sensitivity. Surrogate indices of insulin sensitivity could be used in epidemiological studies but not to define insulin resistance in individual patients or research subjects.

Childhood obesity and dysmetabolic syndrome, in which insulin resistance is a common thread, are escalating pediatric health issues that have created new challenges for clinical diagnosis, treatment, and research (1–4). Therefore, measures of insulin sensitivity are becoming increasingly important as both diagnostic and research tools. The gold standard for assessing insulin sensitivity is the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, which measures the in vivo rate of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal by the total organism (5, 6). Due to the costly, labor-intensive, and invasive nature of the method, it is not applicable in large-scale epidemiological studies. Therefore, surrogate indices of insulin sensitivity have been developed [e.g. the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) and whole-body insulin sensitivity index (WBISI)] (5, 7, 8). In adults, many surrogate indices across a range of glucose tolerance (including diabetes) and categories of weight status and age have been validated and used extensively in epidemiological studies (8, 9). However, most pediatric studies have assessed the use of fasting indices only, whereas data on the relative usefulness of oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)-derived surrogates in pediatrics are lacking (10–16). Furthermore, to our knowledge, no testing of any of these estimates against the euglycemic clamp method in youth with diabetes has been reported. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to examine surrogate indices of insulin sensitivity derived from both fasting and OGTT against hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp-measured insulin sensitivity in obese youth across the spectrum of glucose tolerance, from normal to impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) to diabetes.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

A total of 188 overweight and obese participants (77 Black, 105 White, six biracial; ages 10 to <20 yr old; Tanner stages II–V), including 70 girls with untreated polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), who were participants in our National Institutes of Health-funded K24 Grant of Childhood Insulin Resistance and had complete OGTT and hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp data were included. Some of these participants were reported previously (17–19). There were 101 with normal glucose tolerance (NGT) including 45 with PCOS, 50 with IGT including 25 with PCOS, 23 with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and negative pancreatic autoantibodies, and 14 with a clinical diagnosis of T2DM but with positive autoantibodies, herein called obese type 1 diabetes mellitus (OB-T1DM). Among patients with T2DM, there were six on lifestyle therapy alone, 11 on metformin, two on insulin, and four on metformin and insulin together. Among OB-T1DM patients, there were two on lifestyle therapy alone, three on insulin, two on metformin, and seven on metformin and insulin together. A glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) above 8.5% was an exclusion criterion in subjects with diabetes for patient safety reasons in undergoing the experimental procedures and to minimize the potential impact of glucotoxicity on insulin sensitivity. Participants were recruited through newspaper advertisements, fliers posted in buses and the medical campus, and the outpatient clinics in the Weight Management and Wellness Center and the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology. Participants were screened by history, physical exam, and routine hematological and biochemical tests. Pubertal development was determined by physical examination according to Tanner criteria (20) and confirmed with measurement of plasma testosterone in males, estradiol in females, and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in both males and females. Overweight was defined as age- and sex-specific body mass index (BMI) more than or equal to the 85th and less than the 95th percentile, and obesity was BMI more than or equal to the 95th percentile (21). Procedures were conducted at the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center of the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh, and parental consent and child assent were obtained before any research tests.

Experimental procedures

A 3-h hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp was performed after a 10- to 12-h overnight fast after admission to the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center the previous afternoon. The details of the clamp procedures have been described previously (17, 22, 23). Briefly, participants were prescribed a weight-maintaining diet containing 55% carbohydrate, 15% protein, and 30% fat for 1 wk before and during their hospital stay. Metformin and long- and/or intermediate-acting insulin were discontinued in diabetic participants 48 h before the clamp, and glycemia was controlled with sc injections of rapid-acting insulin, as described previously (18), with the last injection given no less than 6 h before the clamp. Baseline blood samples for fasting glucose and insulin were collected at −30, −20, −10, and 0 min before initiation of insulin infusion (80 mU/m2 · min). Blood glucose was clamped at 100 mg/dl (5.5 mmol/liter) by a variable-rate infusion of 20% dextrose in water.

Either the morning before the clamp or within a 1- to 3-wk period, assigned at random, a 2-h OGTT (1.75 g/kg glucola, maximum 75 g) was performed after a 10- to 12-h overnight fast, as described previously (24). Management of glycemia in patients with diabetes was the same as for the clamp above, except that metformin and long- and/or intermediate-acting insulin were discontinued 24 h before the OGTT. Blood samples were obtained at −15, 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min for determination of glucose and insulin as described previously (24). Body composition was determined by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) with measurement of total fat mass, fat-free mass (FFM), and percent body fat as reported before (17, 18).

Biochemical analyses

Plasma glucose was measured by the glucose oxidase method (Yellow Springs Instrument Co., Yellow Springs, OH). Plasma insulin was analyzed by a commercial RIA (catalog no. 1011; Linco, St. Charles, MO) as before (10). Pancreatic autoantibodies (glutamic acid decarboxylase 65-kDA and insulinoma-associated protein-2) were measured to distinguish obese youth with autoimmune type 1 diabetes from type 2 diabetes as reported before (17, 24).

Calculations of clamp-derived and surrogate indices of insulin sensitivity

Peripheral insulin sensitivity [insulin sensitivity measured by the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp (ISEuClamp)] was calculated during the last 30 min of the clamp to be equal to the rate of exogenous glucose infusion divided by the steady-state clamp insulin concentration and expressed per kilogram body weight (mg/kg · min per μU/ml × 100) or per kilogram FFM (mg/kgFFM · min per μU/ml × 100) (17, 18, 23). Calculations of fasting-derived indices were made using the mean of four fasting glucose (GF) and insulin (IF) concentrations before the start of the euglycemic clamp (−30, −20, −10, and 0 min). Fasting glucose to insulin ratio (GF/IF) and 1/IF,the HOMA for insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IS), which is the reciprocal of HOMA for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) (HOMA2 Calculator at http://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk), and the quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) were calculated according to established methods (5, 7, 25, 26). All indices, including 1/IF and HOMA-IS, were used to express insulin sensitivity, as opposed to resistance, because the euglycemic clamp measures sensitivity, and thus one can assess for positive correlations among all measures. Glucose and insulin data generated during the OGTT were used to calculate the WBISI according to the method of Matsuda and DeFronzo (8). Also, areas under the curve (AUC) for glucose and insulin were calculated by the trapezoidal rule and expressed as the ratio of glucose AUC to insulin AUC (GlucAUC/InsAUC) according to published methods (11, 24).

Statistical analyses

Differences in continuous variables across groups were determined by univariate ANOVA using Bonferroni post hoc mean separation in SPSS (PASW version 18; Chicago, IL). Spearman correlation coefficients were used to relate surrogate (fasting and OGTT derived) indices to clamp-derived measures of insulin sensitivity within glucose tolerance status groups for uniformity because some variables were not distributed normally. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were developed for each index to evaluate the ability of each index to discriminate those subjects with insulin resistance. For purposes of classifying insulin resistance for ROC analysis, a cutoff of 4.5 mg/kg · min per μU/ml measured by hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp was used. This cutoff is the 10th percentile of insulin sensitivity in a cohort of normal-weight youth as previously described by us (27). All other data analyses and figures are based on clamp-measured insulin sensitivity expressed per kilogram FFM unless otherwise indicated. Data are presented as mean ± se, and a P value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Subject characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Subject characteristics by glucose tolerance group

| NGT (1), n = 101 | IGT (2), n = 50 | T2DM (3), n = 23 | OB-T1DM (4), n = 14 | P, ANOVA |

P, post hoc |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 1 vs. 4 | 2 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 4 | 3 vs. 4 | ||||||

| Age (yr) | 14.8 ± 0.2 | 14.7 ± 0.3 | 15.0 ± 0.4 | 14.1 ± 1.6 | 0.60 | ||||||

| Sex (% male) | 38 | 32 | 43 | 36 | 0.81 | ||||||

| Tanner stage (% IV–V) | 88 | 88 | 87 | 79 | 0.29 | ||||||

| Race (% African-American, White, biracial) | 44, 51, 5 | 36, 62, 2 | 43, 57, 0 | 36, 64, 0 | 0.91 | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34.7 ± 0.6 | 36.5 ± 0.9 | 35.9 ± 1.1 | 30.6 ± 1.4 | 0.01 | NS | NS | 0.10 | NS | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| BMI percentile | 97.7 ± 0.2 | 98.7 ± 0.2 | 98.8 ± 0.1 | 95.7 ± 1.0 | <0.001 | 0.04 | NS | 0.01 | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| % overweight/% obese | 10/90 | 2/98 | 0/100 | 29/71 | |||||||

| Fat mass (kg) | 40.7 ± 1.4 | 43.0 ± 1.7 | 40.1 ± 2.1 | 32.9 ± 3.1 | 0.07 | ||||||

| FFM (kg) | 50.5 ± 1.0 | 51.3 ± 1.4 | 53.3 ± 2.4 | 46.3 ± 2.6 | 0.22 | ||||||

| Total body fat (%) | 42.8 ± 0.8 | 44.1 ± 0.7 | 42.1 ± 1.4 | 39.9 ± 2.2 | 0.21 | ||||||

| HbA1C (%) | 5.4 ± 0.04 | 5.4 ± 0.06 | 6.6 ± 0.14 | 6.3 ± 0.29 | <0.001 | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | NS |

NS, Not significant.

Participants were categorized according to their glucose tolerance status (Table 1): NGT, IGT, antibody-negative T2DM, and antibody-positive OB-T1DM. There were no significant differences among the groups with respect to age, sex, race, and Tanner stage. The OB-T1DM had the lowest BMI and BMI percentile. However, fat mass, FFM, and percent body fat from DEXA were not significantly different across groups. The HbA1C was higher in both diabetic groups than nondiabetic NGT and IGT groups (Table 1).

Measures of clamp-derived and surrogate estimates of insulin sensitivity (Table 2)

Table 2.

Clamp-derived measures and surrogate indices of insulin sensitivity by glucose tolerance group

| NGT (1), n = 101 | IGT (2), n = 50 | T2DM (3), n = 23 | OB-T1DM (4), n = 14 | P, ANOVA |

P, post hoc |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 1 vs. 4 | 2 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 4 | 3 vs. 4 | ||||||

| SIEuClamp (mg/kg · min per μU/ml) | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.03 | NS | NS | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| SIEuClamp (mg/kg FFM · min per μU/ml) | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 5.7 ± 0.7 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.01 | NS | NS | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| GF (mg/dl) | 94.8 ± 0.6 | 96.9 ± 1.0 | 117 ± 4.5 | 131 ± 11 | <0.001 | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| IF (μU/ml) | 32.3 ± 1.6 | 48.8 ± 4.2 | 44.8 ± 5.5 | 25.1 ± 2.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.08 | NS | NS | <0.01 | 0.05 |

| 1/IF | 0.038 ± 0.002 | 0.028 ± 0.002 | 0.030 ± 0.003 | 0.047 ± 0.005 | <0.001 | <0.01 | NS | NS | NS | <0.01 | 0.02 |

| GF/IF | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 6.0 ± 0.8 | <0.001 | <0.01 | NS | <0.001 | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| QUICKI | 0.292 ± 0.002 | 0.279 ± 0.003 | 0.275 ± 0.004 | 0.290 ± 0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| HOMA-IS | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | <0.001 | <0.01 | 0.06 | NS | NS | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| WBISI | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.02 | NS | NS | <0.01 | 0.07 |

| GlucAUC/InsAUC | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.81 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 1.0 | <0.001 | NS | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

NS, Not significant.

Fasting plasma glucose levels were significantly higher in youth with diabetes compared with IGT and NGT and were highest in OB-T1DM. Fasting plasma insulin was lowest in OB-T1DM and highest in IGT. Consequently, fasting glucose (GF)/fasting insulin (IF) was highest in OB-T1DM and was lowest in subjects with IGT. Clamp-measured insulin sensitivity was lowest in T2DM and IGT and highest in NGT and OB-T1DM; the latter two were not different from each other. Indices 1/IF, HOMA-IS, QUICKI, and WBISI were lowest in T2DM and IGT subjects compared with NGT and OB-T1DM, with no significant difference between the latter two groups. Ratio of glucose AUC to insulin AUC (GlucAUC/InsAUC) was lowest in IGT and highest in OB-T1DM because of very low insulin levels and high glucose levels. GlucAUC/InsAUC was not different between NGT and IGT (Table 2).

Relationships between clamp-measured insulin sensitivity and the surrogate estimates (Figs. 1–4)

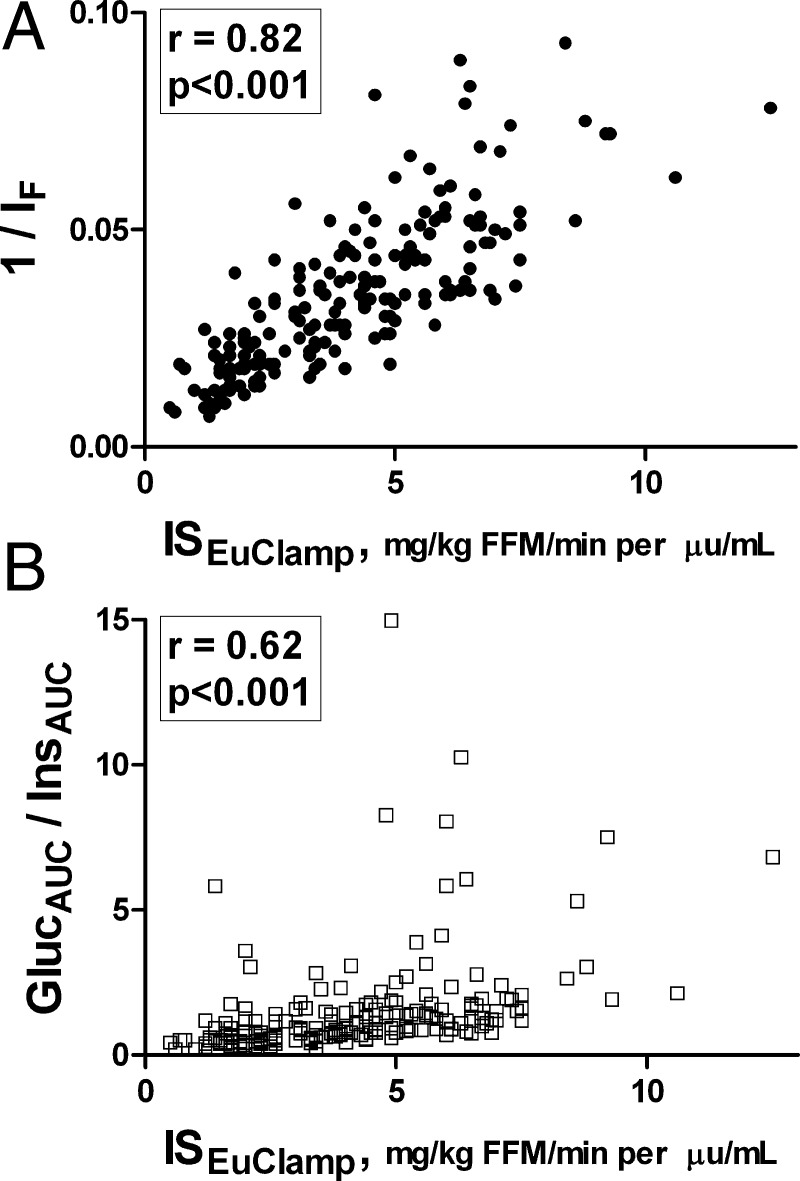

Fig. 1.

The correlations between clamp-measured insulin sensitivity and surrogate estimates (A, 1/IF; B, GlucAUC/InsAUC) of insulin sensitivity in the total population of overweight/obese adolescents.

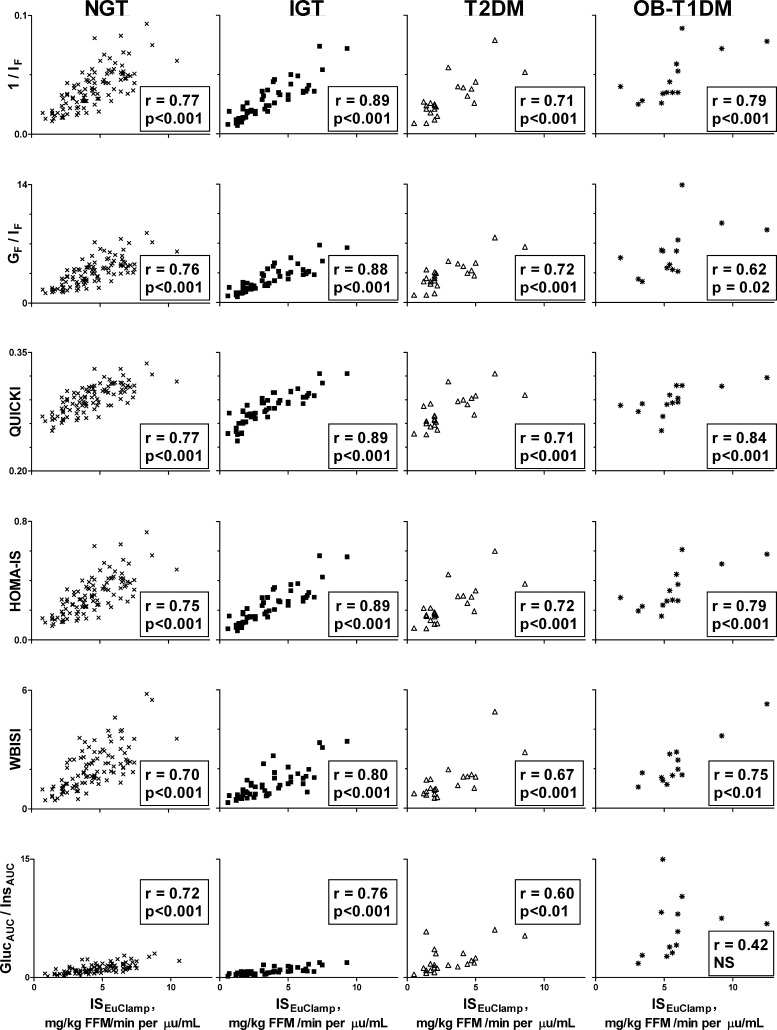

Fig. 2.

Correlations between clamp-measured insulin sensitivity and surrogate estimates of fasting and OGTT-derived insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese adolescents shown separately in each group: NGT, IGT, T2DM, and OB-T1DM.

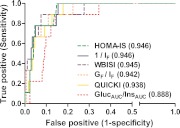

Fig. 3.

ROC curves of of 1/IF, GF/IF, QUICKI, HOMA-IS, WBISI, and GlucAUC/InsAUC with all groups combined. A cutoff of 4.5 mg/kg · min per μU/ml was used to define insulin resistance (27). The area under the ROC curve for each index is in parentheses.

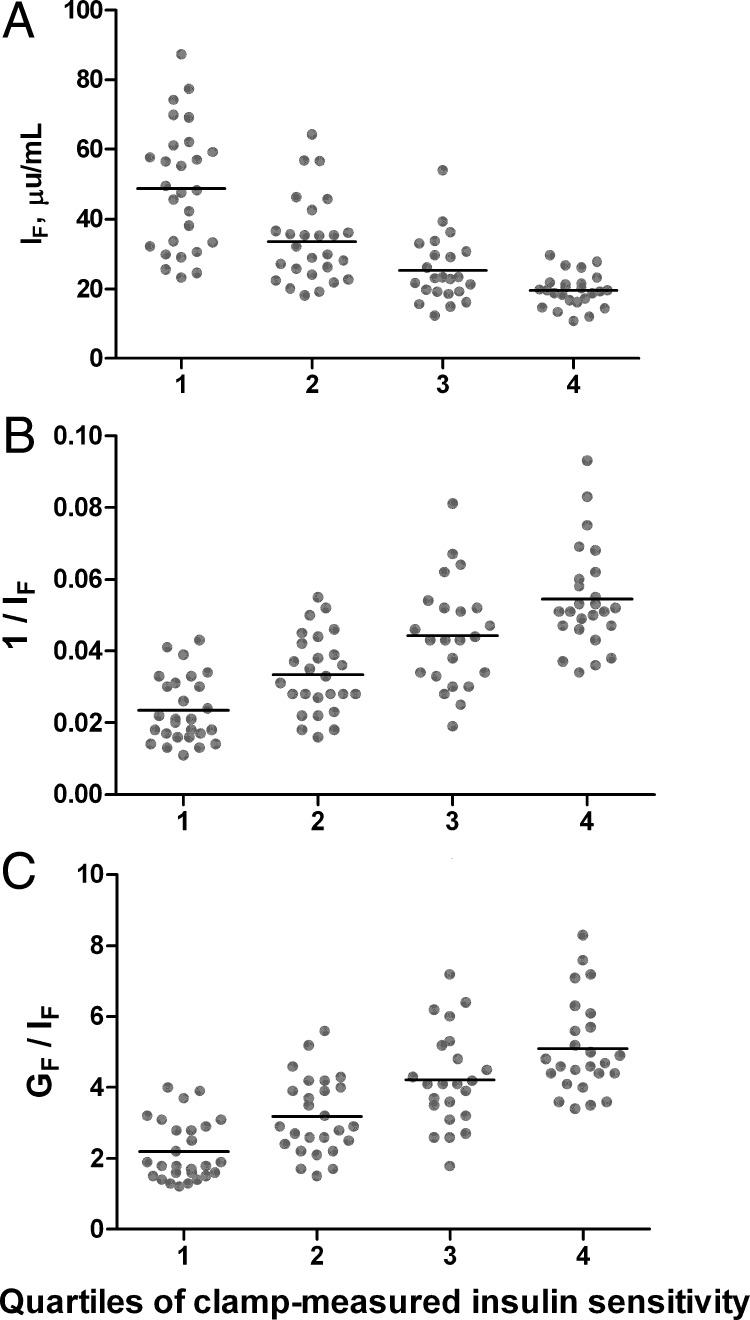

Fig. 4.

Distribution of IF (A), 1/IF (B), and GF/IF (C) according to quartiles of clamp-measured insulin sensitivity in NGT subjects (n = 101). Black bars represent mean, and points represent individual values. Quartiles of clamp-measured insulin sensitivity were defined as quartile 1 (most insulin resistant), at or below 25th percentile (insulin sensitivity ≤3.1 mg/kg FFM · min per μU/ml); 2, higher than 25th to at or below 50th percentile (>3.1 to ≤4.4); 3, higher than 50th to at or below 75th percentile (>4.4 to ≤5.8); and 4 (most insulin sensitive), higher than 75th percentile (>5.8).

Overall, the various estimates of insulin sensitivity showed correlation coefficients ranging from 0.62 (GlucAUC/InsAUC) to 0.82 (1/IF) with ISEuClamp (Fig. 1). Correlation coefficients were intermediate for other indices: GF/IF, r = 0.78; QUICKI, r = 0.80; HOMA-IS, r = 0.81; WBISI, r = 0.77. All correlations were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Figure 2 depicts the correlations in each glucose tolerance group separately. In general, 1/IF, HOMA, and QUICKI had the highest correlations with clamp insulin sensitivity regardless of glucose tolerance group (Fig. 2). The lowest correlations were with WBISI and GlucAUC/InsAUC. The correlations between GF/IF and ISEuClamp were highest in NGT and IGT, intermediate in T2DM, and lowest in OB-T1DM. In the OB-T1DM group, the highest correlation was with QUICKI, followed by 1/IF and HOMA-IS.

The area under the ROC curve (ROCAUC) for each index ranged from 0.888–0.946 (Fig. 3). GlucAUC/InsAUC was the least useful discriminator of insulin resistance, whereas the ROCAUC was 0.94 or higher for all of the other surrogates measures, indicating high sensitivity and specificity for detection of insulin resistance according to the criteria used here. Figure 4 illustrates the significant overlap in individual values of IF, 1/IF, and GF/IF across quartiles of clamp-measured insulin sensitivity.

Correlations in males separate from females

All correlations calculated within each sex were significant (P < 0.05) unless otherwise noted. In males with NGT (n = 38), the highest correlations were between clamp and 1/IF, GF/IF, and HOMA-IS (r = 0.73 for each), whereas the lowest correlation was with WBISI (r = 0.55). In males with IGT (n = 16), the highest correlations were with 1/IF and QUICKI (r = 0.82 for both) and the lowest was with WBISI (r = 0.78). In T2DM males (n = 10), the highest correlation was between clamp and QUICKI (r = 0.92), and the lowest correlation was with WBISI (r = 0.84). In OB-T1DM males (n = 5), the highest correlations were with 1/IF, HOMA-IS, and QUICKI (r = 0.90 for each), and the remaining fasting and OGTT-based indices were nonsignificant.

In females with NGT (n = 63), the highest correlations were between clamp and 1/IF, GF/IF, and GlucAUC/InsAUC (r = 0.79 for each) and the lowest correlation was with QUICKI (r = 0.75). In IGT females (n = 34), the highest correlation was with GF/IF (r = 0.92), and the lowest was with GlucAUC/InsAUC (r = 0.70). In females with T2DM (n = 13), all correlations were nonsignificant. In T1DM females (n = 9), the highest correlation was with QUICKI (r = 0.94), and the lowest was with WBISI (= 0.71).

Discussion

The present study evaluated surrogate estimates of insulin sensitivity in obese youth against the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp and, for the first time, included youth diagnosed with diabetes. Data presented here indicate that 1) fasting-derived indices of insulin sensitivity show consistently higher correlations with clamp-derived measures of insulin sensitivity than OGTT-derived indices in obese youth with varying degrees of glucose tolerance, 2) HOMA or QUICKI do not seem to have any added advantage over the simple measure of 1/IF because all three show similar correlations with clamp-measured insulin sensitivity and similar utility for prediction of insulin sensitivity according to ROC analysis, and 3) it is inappropriate to use any surrogate measure as a means of diagnosing insulin resistance in any single individual (i.e. using cutoffs to define a patient as insulin sensitive or insulin resistant), because the overlap of these estimates across quartiles of clamp-measured insulin sensitivity is great.

Importantly, OGTT-derived estimates of insulin sensitivity did not outperform those derived from fasting samples when compared with the gold standard of clamp methodology. Guzzaloni et al. (28) also reported no advantage of OGTT-derived indices over fasting-derived indices for identification of significant differences in insulin sensitivity across pubertal stages and sexes in obese children. Yeckel et al. (16) reported similar correlation coefficients to the present study for WBISI and clamp sensitivity, but a lower correlation (r = −0.57) between HOMA-IR and clamp, in a much smaller group (n = 38) of obese NGT and IGT youth. This lower correlation with HOMA-IR may be due to the smaller number of participants and differences in the racial makeup of the populations, the number of fasting samples used to derive HOMA-IR (12), and the expression of insulin sensitivity, which is per FFM in our study.

In studies comparing surrogate indices against insulin sensitivity derived from a minimal model (SiMINMOD) frequently sampled iv glucose tolerance test (FSIVGTT), correlations with HOMA-IR and with fasting insulin were significant (10, 13). In agreement with the present report, Rössner et al. (13) indicated that QUICKI showed similar results to HOMA-IR and, in a later publication, indicated that HOMA and QUICKI have an equal ability to predict insulin sensitivity (12). In contrast, however, the correlations reported (13) for the SiMINMOD were lower than reported here with the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp. The contrast between the latter study and ours could stem from differences in the study population. Our study includes only pubertal adolescents with the majority (79–88%) in Tanner stage IV–V, in contrast to the population studied by Rössner et al. (13), which included children in Tanner stages I/II/III/IV/V with a significant imbalance between females and males among prepubertal and pubertal groups (Tanner V, 46.8% of females vs. 20.7% of males, and Tanner I, 8.3% of females vs. 37.8% of males). Bearing in mind that puberty is a significant determinant of insulin sensitivity, with gender-related differences in pubertal stage and insulin sensitivity (29), including youth with varying stages of puberty may be partly responsible for the observed differences between the two studies. Also, the present study reported Spearman correlations, whereas the other (13) reported partial correlations of ln-transformed data adjusted for BMI and age. The gender-specific correlations reported by Rössner et al. (13) were somewhat stronger in males, the opposite of others' findings using a clamp (14), which may be due to the imbalance of each gender within the pubertal stages discussed above. The present study indicates somewhat greater correlations in females than males for NGT, IGT, and OB-T1DM, but not in T2DM. However, definitive conclusions regarding sex effects in the diabetic groups should not be drawn here because of the small numbers of subjects when subdivided by sex (T2DM, 10 male and 13 female; OB-T1DM, five male and nine female). A relatively small study in 18 obese children and adolescents (seven prepubertal and 11 pubertal) who repeated the FSIVGTT up to three times showed high correlations (r > 0.85) between SiMINMOD and multiple surrogate indices: HOMA-IR, QUICKI, and GF/IF (30). However, Cutfield et al. (10) showed virtually no relationship between QUICKI and SiMINMOD in lean, prepubertal children despite significant correlations between SIMINMOD and either HOMA-IR or IF. A low or nonexistent correlation to SiMINMOD may be a systematic reflection of QUICKI's original derivation from the clamp and not SIMINMOD, instead of evidence against the ability of QUICKI to estimate insulin sensitivity. Thus, factors that could potentially explain the reported differences in the correlations between surrogates and SiMINMOD include differing study populations (age, race, Tanner stage, etc.) and different analytical methods and sample size (12). Also, use of the 90-min FSIVGTT protocol modified for pediatric use employed by some (10) may introduce variation among reports.

The only studies examining surrogate indices against clamp-derived measures in a pediatric population were from Yeckel et al. (16) as mentioned previously; Uwaifo et al. (15) reporting on a relatively small (n = 31) group of NGT normal-weight and overweight youth; Schwartz et al. (14) reporting a well executed study on a large (n = 323) cohort of normal-weight, overweight, and obese adolescents; and another study by us (11) examining a large sample (n = 156) of normal-weight and obese prepubertal children and pubertal adolescents. None of these studies, however, included youth with diabetes, and there were only a small number with IGT (11, 16). These studies demonstrated the usefulness of fasting-derived surrogate indices in estimating insulin sensitivity in prepubertal, pubertal lean, overweight, and obese children (11, 14, 15). Uwaifo et al. (15) found a stronger correlation between QUICKI and clamp-derived insulin sensitivity than with HOMA. However, Gungor et al. (11) showed identical correlations between either QUICKI or HOMA and clamp-derived insulin sensitivity, similar to our present findings. Contrary to our current study, however, this previous study included lean and prepubertal children and none with diabetes (11). Schwartz et al. (14) reported lower correlations than reported here in adolescents with 85th percentile or higher BMI. However, they used a lower rate of insulin infusion during the clamp than the current report. In the absence of stable isotopes to measure hepatic glucose production (HGP), the lower insulin infusion rates may result in incomplete suppression of HGP in those subjects with BMI at or above the 85th percentile. Also, the present study expressed insulin sensitivity as the insulin-stimulated glucose disposal over the last 30 min of the clamp, divided by the steady-state insulin over the same period (from 150–180 min, the mean of four determinations), whereas Schwartz et al. (14) reported the insulin-stimulated glucose disposal over 40 min corrected for the ln-transformed steady-state insulin over only 20 min (160–180 min). Lastly, lean body mass, used to adjust insulin sensitivity, was predicted from skinfold thickness in the study by Schwartz et al. (14), whereas the current work used DEXA. With respect to OGTT-derived estimates of insulin sensitivity, only Yeckel et al. (16) compared WBISI with clamp, showing a stronger correlation for WBISI than HOMA-IR. However, the correlations reported were to the clamp insulin-stimulated glucose disposal rate (M or Rd, milligrams per square meter per minute), which is not corrected for the prevailing clamp steady-state insulin level when one calculates insulin sensitivity as is the case in our study.

In all the groups and irrespective of glucose tolerance status, the simple calculation of 1/IF had comparable correlations to those observed with the more complicated calculations of HOMA or QUICKI with clamp insulin sensitivity. Thus, the more complicated calculations of HOMA and QUICKI, as well as OGTT-based surrogate estimates of insulin sensitivity, may be unnecessary because they do not provide better estimation of insulin sensitivity than that obtained from fasting insulin alone (12). Similar was the case with GF/IF, except in obese youth with type 1 diabetes in whom the correlation with clamp-measured insulin sensitivity dropped precipitously because of the significantly higher fasting glucose and lower insulin levels resulting in a higher GF/IF ratio. This higher ratio is not indicative of higher insulin sensitivity but rather is a reflection of the severe insulin deficiency and the consequent hyperglycemia in these patients. It remains to be determined what the correlations would be between surrogate indices and clamp-measured insulin sensitivity in normal-weight youth with a more classically diagnosed type 1 diabetes.

The 1/IF and HOMA yielded the highest ROCAUC, indicating the greatest accuracy (combination of sensitivity and specificity) for identifying insulin resistance according to the cutoff criteria used. Regarding the OGTT-derived indices, WBISI has a comparably high ROCAUC as well, but GlucAUC/InsAUC had the lowest sensitivity and specificity of all. However, when ROC analysis was conducted in nondiabetic subjects only, the ROCAUC for GlucAUC/InsAUC was comparable to the other surrogate indices (data not shown). Overall and for all groups combined, all indices gave excellent ROCAUC values (≥0.94, except GlucAUC/InsAUC) for identification of insulin resistance based on a cutoff derived in normal-weight children (27). Consistently high values for ROCAUC may be enhanced by the high prevalence of insulin resistance in this overweight/obese cohort, which included subjects known to have low insulin sensitivity (IGT and diabetic individuals).

The present data show significant overlap in surrogate estimates of insulin sensitivity across quartiles of clamp-measured insulin sensitivity. Therefore, it is improper to use an absolute cutoff value, as commonly practiced, for fasting insulin and other surrogates (31–33) to define insulin resistance in any one individual patient or research subjects (6). Although surrogate estimates of insulin sensitivity may prove useful in large-scale epidemiological studies, their use to diagnose individuals as insulin resistant vs. sensitive based on arbitrary cutoffs is uncalled for and should be abandoned. Furthermore, because of the wide differences in the strength of the correlations reported in the literature between clamp-measured sensitivity and surrogate indices, the former should be the experimental approach in small-scale studies where accurate measurements of peripheral tissue insulin sensitivity are needed.

The current observation of lower correlations between OGTT-derived indices and clamp insulin sensitivity compared with fasting indices may stem from the poor reproducibility of the OGTT in obese youth (34). We previously showed that the percent positive agreement between two OGTT is low for both impaired fasting glucose and IGT (22.2 and 27.3%) (34). Furthermore, the degree of insulin deficiency will modulate the degree of glycemia achieved during the OGTT; thus, the OGTT-derived WBISI or GluAUC/InsAUC may not reflect insulin sensitivity but, instead and importantly, insulin secretion. Because performing an OGTT is more time, energy, and cost requiring than a fasting blood sample, its use in determining insulin sensitivity remains unjustified unless one needs to determine glucose tolerance status.

A potential limitation of the current study that may not be consistent with real-life experiences is that fasting-derived indices were calculated based on four samples collected 10 min apart at the baseline of the euglycemic clamp. This collection followed controlled overnight conditions mediated by the admission of the participant to the hospital the previous afternoon. It is important to bear in mind that significant intra-individual variations have been reported in both fasting glucose and insulin levels, and surrogates from one vs. four fasting samples yield variable results (12, 34, 35). Also, in the absence of tracer use during the clamp, it is uncertain that HGP was suppressed in all subjects, even though the use of the high-rate insulin infusion would have in all likelihood done so. Another limitation is that the patients with diabetes were on a variety of treatments including insulin and metformin. In diabetic patients, any type of treatment may modify the natural state of insulin action and/or secretion, unless the patient is studied at diagnosis before institution of any therapy or unless treatment is discontinued for prolonged periods, neither of which is ethically acceptable. However, the scientific literature, replete with such experiments that have the same limitations, has remarkably advanced our understanding of the pathophysiological changes in insulin action and secretion in T2DM and their modulations with various therapeutic approaches (36, 37). Also, diabetics with an HbA1C above 8.5% were not studied, and it is possible that the strength of the correlations between surrogate indices may vary with the level of glycemic control. Lastly, a minor limitation is that the order of the clamp study and OGTT was random and not standardized.

In conclusion, we present for the first time an evaluation of fasting- and OGTT-derived indices for insulin sensitivity against the gold-standard hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp in obese youth across the continuum of glucose tolerance, including obese diabetic children. These data show that OGTT-derived surrogates do not offer additional advantage to fasting indices, especially considering the additional cost and the longer duration of an OGTT as well as the additional burden to the research participants and staff. Indices 1/IF, HOMA, and QUICKI were the best surrogate estimates, with no appreciable advantage of the latter two over the simple 1/IF, as previously indicated (6, 14). Such findings may be helpful in large-scale epidemiological studies, whether or not the natural history or the effect of therapeutic interventions on insulin resistance in childhood is being investigated. There is no rational justification for using such indices in the clinical setting or on an individual basis. Additional larger-scale studies of youth with T2DM or OB-T1DM may prove beneficial, especially with the escalating rates of obesity in children with type 1 diabetes and its consequence of insulin resistance (38).

Acknowledgments

These studies would not have been possible without the nursing staff of the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center, the devotion of the research team (Nancy Guerra, CRNP; Sabrina Kadri; Kristin Porter, RN; Sally Foster, RN, CDE; Lori Bednarz, RN, CDE), the laboratory expertise of Resa Stauffer, and most importantly, the commitment of the study participants and their parents.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant RO1 HD27503 (to S.A.), K24 HD01357 (to S.A.), Richard L. Day Endowed Chair (to S.A.), Department of Defense (to S.A., S.L., L.G., and H.T.), American Diabetes Association Junior Faculty Award (to S.J.L.), Thrasher Research Fund (to F.B.), and MO1 RR00084 (General Clinical Research Center) and UL1 RR024153 (Clinical and Translational Science Award).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AUC

- Area under the curve

- BMI

- body mass index

- DEXA

- dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- FFM

- fat-free mass

- FSIVGTT

- frequently sampled iv glucose tolerance test

- GF

- fasting glucose

- GlucAUC/InsAUC

- ratio of glucose AUC to insulin AUC

- HbA1C

- glycosylated hemoglobin

- HGP

- hepatic glucose production

- HOMA

- homeostasis model assessment

- HOMA-IS

- HOMA for insulin sensitivity

- HOMA-IR

- HOMA for insulin resistance

- IF

- fasting insulin

- IGT

- impaired glucose tolerance

- ISEuClamp

- insulin sensitivity measured by the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp

- NGT

- normal glucose tolerance

- OB-T1DM

- obese type 1 diabetes mellitus

- OGTT

- oral glucose tolerance test

- PCOS

- polycystic ovary syndrome

- QUICKI

- quantitative insulin sensitivity check index

- ROC

- receiver-operating characteristic

- SiMINMOD

- insulin sensitivity derived from a minimal model

- T2DM

- type 2 diabetes mellitus

- WBISI

- whole-body insulin sensitivity index.

References

- 1. Rosenbloom AL, Joe JR, Young RS, Winter WE. 1999. Emerging epidemic of type 2 diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care 22:345–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pinhas-Hamiel O, Zeitler P. 2005. The global spread of type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents. J Pediatr 146:693–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. 2002. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet 360:473–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cook S, Weitzman M, Auinger P, Nguyen M, Dietz WH. 2003. Prevalence of a metabolic syndrome phenotype in adolescents: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 157:821–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Trout KK, Homko C, Tkacs NC. 2007. Methods of measuring insulin sensitivity. Biol Res Nurs 8:305–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levy-Marchal C, Arslanian S, Cutfield W, Sinaiko A, Druet C, Marcovecchio ML, Chiarelli F. 2010. Insulin resistance in children: consensus, perspective, and future directions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:5189–5198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. 1985. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28:412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. 1999. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 22:1462–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bonora E, Targher G, Alberiche M, Bonadonna RC, Saggiani F, Zenere MB, Monauni T, Muggeo M. 2000. Homeostasis model assessment closely mirrors the glucose clamp technique in the assessment of insulin sensitivity: studies in subjects with various degrees of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 23:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cutfield WS, Jefferies CA, Jackson WE, Robinson EM, Hofman PL. 2003. Evaluation of HOMA and QUICKI as measures of insulin sensitivity in prepubertal children. Pediatr Diabetes 4:119–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gungor N, Saad R, Janosky J, Arslanian S. 2004. Validation of surrogate estimates of insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in children and adolescents. J Pediatr 144:47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rössner SM, Neovius M, Mattsson A, Marcus C, Norgren S. 2010. HOMA-IR and QUICKI: decide on a general standard instead of making further comparisons. Acta Paediatr 99:1735–1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rössner SM, Neovius M, Montgomery SM, Marcus C, Norgren S. 2008. Alternative methods of insulin sensitivity assessment in obese children and adolescents. Diabetes Care 31:802–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schwartz B, Jacobs DR, Jr, Moran A, Steinberger J, Hong CP, Sinaiko AR. 2008. Measurement of insulin sensitivity in children. Diabetes Care 31:783–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Uwaifo GI, Fallon EM, Chin J, Elberg J, Parikh SJ, Yanovski JA. 2002. Indices of insulin action, disposal, and secretion derived from fasting samples and clamps in normal glucose-tolerant black and white children. Diabetes Care 25:2081–2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yeckel CW, Weiss R, Dziura J, Taksali SE, Dufour S, Burgert TS, Tamborlane WV, Caprio S. 2004. Validation of insulin sensitivity indices from oral glucose tolerance test parameters in obese children and adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:1096–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bacha F, Lee S, Gungor N, Arslanian SA. 2010. From prediabetes to type 2 diabetes in obese youth: pathophysiological characteristics along the spectrum of glucose dysregulation. Diabetes Care 33:2225–2231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tfayli H, Bacha F, Gungor N, Arslanian S. 2009. Phenotypic type 2 diabetes in obese youth: insulin sensitivity and secretion in islet cell antibody-negative versus -positive patients. Diabetes 58:738–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee S, Guerra N, Arslanian S. 2010. Skeletal muscle lipid content and insulin sensitivity in Black versus White obese adolescents: is there a racial difference? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:2426–2432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tanner JM. 1969. Growth and endocrinology in the adolescent. In: Gardner L, ed. Endocrine and genetic diseases of childhood. Philadelphia: Saunders; 19–60 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rosner B, Prineas R, Loggie J, Daniels SR. 1998. Percentiles for body mass index in US children 5 to 17 years of age. J Pediatr 132:211–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burns SF, Lee S, Arslanian SA. 2009. In vivo insulin sensitivity and lipoprotein particle size and concentration in Black and White children. Diabetes Care 32:2087–2093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Defronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R. 1979. Glucose clamp technique: method for quantifying insulin-secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol 237:E214–E223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tfayli H, Bacha F, Gungor N, Arslanian S. 2010. Islet cell antibody-positive versus -negative phenotypic type 2 diabetes in youth: does the oral glucose tolerance test distinguish between the two? Diabetes Care 33:632–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Katz A, Nambi SS, Mather K, Baron AD, Follmann DA, Sullivan G, Quon MJ. 2000. Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index: a simple, accurate method for assessing insulin sensitivity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:2402–2410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. 2004. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care 27:1487–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee S, Gungor N, Bacha F, Arslanian S. 2007. Insulin resistance: link to the components of the metabolic syndrome and biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction in youth. Diabetes Care 30:2091–2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guzzaloni G, Grugni G, Mazzilli G, Moro D, Morabito F. 2002. Comparison between β-cell function and insulin resistance indexes in prepubertal and pubertal obese children. Metabolism 51:1011–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moran A, Jacobs DR, Jr, Steinberger J, Hong CP, Prineas R, Luepker R, Sinaiko AR. 1999. Insulin resistance during puberty: results from clamp studies in 357 children. Diabetes 48:2039–2044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Conwell LS, Trost SG, Brown WJ, Batch JA. 2004. Indexes of insulin resistance and secretion in obese children and adolescents: a validation study. Diabetes Care 27:314–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Esteghamati A, Ashraf H, Khalilzadeh O, Zandieh A, Nakhjavani M, Rashidi A, Haghazali M, Asgari F. 2010. Optimal cut-off of homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome: third national surveillance of risk factors of non-communicable diseases in Iran (SuRFNCD-2007). Nutr Metab 7:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Silfen ME, Manibo AM, McMahon DJ, Levine LS, Murphy AR, Oberfield SE. 2001. Comparison of simple measures of insulin sensitivity in young girls with premature adrenarche: the fasting glucose to insulin ratio may be a simple and useful measure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:2863–2868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Love-Osborne K, Sheeder J, Zeitler P. 2008. Addition of metformin to a lifestyle modification program in adolescents with insulin resistance. J Pediatr 152:817–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Libman IM, Barinas-Mitchell E, Bartucci A, Robertson R, Arslanian S. 2008. Reproducibility of the oral glucose tolerance test in overweight children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:4231–4237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sunehag AL, Treuth MS, Toffolo G, Butte NF, Cobelli C, Bier DM, Haymond MW. 2001. Glucose production, gluconeogenesis, and insulin sensitivity in children and adolescents: an evaluation of their reproducibility. Pediatr Res 50:115–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Preumont V, Hermans MP, Brichard S, Buysschaert M. 2010. Six-month exenatide improves HOMA hyperbolic product in type 2 diabetic patients mostly by enhancing beta-cell function rather than insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Metab 36:293–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Juurinen L, Kotronen A, Granér M, Yki-Järvinen H. 2008. Rosiglitazone reduces liver fat and insulin requirements and improves hepatic insulin sensitivity and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes requiring high insulin doses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:118–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Libman IM, Pietropaolo M, Arslanian SA, LaPorte RE, Becker DJ. 2003. Changing prevalence of overweight children and adolescents at onset of insulin-treated diabetes. Diabetes Care 26:2871–2875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]