Abstract

Liposomal amphotericin B has been used as an alternative treatment of mucosal leishmaniasis, but the optimal dose is not established. We retrospectively reviewed the clinical outcome of eight patients with mucosal leishmaniasis treated with liposomal amphotericin B. The mean total dose was 35 mg/kg (range 24–50 mg/kg), which resulted in the healing of all the lesions in all patients and no recurrences were observed during the follow-up period (mean 25 months; range 7–40 months).

Tegumentary American leishmaniasis is a zoonotic disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania, transmitted through the bite of various species of female phlebotomine sandflies1; the disease is an important public health problem in Brazil and is expanding its range through the state of São Paulo. Nevertheless, in terms of research, prevention, and control initiatives, leishmaniasis is a neglected disease that draws little interest from financial donors, public health authorities, and professionals.1 The mucosal leishmaniasis is the most severe form of the cutaneous disease, caused by progressively destructive lesions of the nasal, oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal tissues, causing severe facial deformation and respiratory disturbances.2

Pentavalent antimonials are the current drugs of choice for the treatment of mucosal leishmaniasis (ML), although they are far from ideal because of serious adverse side effects.3 Similarly, pentamidine and amphotericin B deoxycholate are parenteral agents that can be poorly tolerated by patients and require close medical supervision to avoid well-known serious adverse events with both drugs. Liposomal amphotericin B has been used as an alternative treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis and, in comparison to conventional amphotericin B deoxycholate, has demonstrated a similar efficacy and lower toxic effects, although the optimum dosing regimen is undefined.4,5

We performed a retrospective study in eight patients to evaluate the efficacy and total dose of liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome NeXtar, San Dimas, CA) used for the treatment and clinical cure of ML. This study had the permission and the Institutional approval provided by the Clinic of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases, Hospital das Clinicas of University of São Paulo and it was considered respectful and ethical in its treatment of human subjects.

The drug was administered in 3–5 mg/kg/day doses. The dosage was determined by the prescriber and the duration of the treatment. Doses and outcomes are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics and outcomes of patients with mucosal leishmaniasis treated with liposomal amphotericin B*

| Sex/age, years | Lesion site | Previous treatment | Contraindication(s)† | Total cumulative dose, mg | Weight, Kg | Dose mg/Kg | Outcome | Duration of hospital stay/follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 M/64 | Nasal septum | None | AVR | 2100 | 65 | 32.3 | Cure | 15 days/8 months |

| 2 M/40 | Nasal septum | None | AVR | 2910 | 100 | 29.1 | Cure | 15 days/9 months |

| 3 M/84 | Nasal septum | None | AVR, CRF | 2000 | 70 | 28.6 | Cure | 23 days/40 months |

| 4 M/76 | Nasal septum | (2 years earlier) | AVR, ARF | 3000 | 60 | 50 | Cure | 21 days/37 months |

| 5 M/47 | Palate, larynx | (3 years earlier) | AVR, DM | 3000 | 60 | 50 | Cure | 40 days/35 months |

| 6 M/66 | Nasal septum | (9 days earlier) | ARF | 2600 | 68 | 38.2 | Cure | 24 days/25 months |

| 7 M/35 | Nasal septum, palate | (10 days earlier) | AVR | 2250 | 85 | 26.5 | Cure | 21 days/40 months |

| 8 M/52 | Nasal septum, palate | (5 days earlier) | ARF | 2240 | 93 | 24 | Cure | 14 days/7 months |

| Mean | 25,125 | 75,125 | 34.83 | 21,625 days/25,125 months |

ARF = acute renal failure; AVR = altered ventricular repolarization; CRF = chronic renal failure; DM = diabetes mellitus.

Contraindications to the use of antimonials, pentamidine, or deoxycholate amphotericin B.

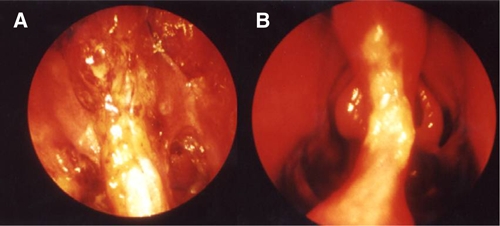

All patients received liposomal amphotericin B because there was contraindication for antimonials. The respective contraindications are described in the Table 1. Patient nos. 3, 6, 7, and 8 were from the state of Bahia, localized in the Northeast. Patient 1 was from Paraná, a state localized in the South, and other patients (2, 4, and 5) were from the state of Sao Paulo. The patient 8 had human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) under antiviral therapy. The cure and failure criteria were previously described.6 Figure 1 describes a case showing the image of nasal septum before and after the treatment of ML.

Figure 1.

(A) Patient no. 8, nasofibrolaryngoscopy of nasal cavities showing mucosal edema and granuloma of nasal septum before treatment and (B) the healed lesion after treatment, allowing the visualization of the middle turbinate.

Side effects were observed in six patients and included chills, myalgia, back pain, nausea, and headache. Reduced glomerular filtration rate and hypokalemia were observed in two patients, but both levels returned to normal 2 days after the discontinuation of the drug and its subsequent reintroduction. All of the patients were clinically cured, and no failure or recurrence of disease was observed during the follow-up period (range 7–40 months; mean 25 months). Retreatment was not required for any of the patients.

Lipid formulations of amphotericin B have been effective treatments for visceral leishmaniasis in many countries, including Brazil.7–9 This formulation is packaged with cholesterol and other phospholipids within a small unilamellar liposome that binds to parasite ergosterol precursors, causing disruption of the parasite membrane without substantial harm to mammalian cell membranes. Additionally, the concentration of liposomal amphotericin B is high in macrophages, which enhances drug concentration in infected tissues, particularly the liver and spleen.10 This is an important benefit of the liposomal formulation, as Leishmania parasites are often present in host macrophages.

Despite a small overall number of cases evaluated, the results of this study are similar to findings in previous studies.4,5 The current World Health Organization (WHO) Technical Report Series recommends 2–3 mg/kg daily up to a total dose of 40–60 mg/kg of liposomal amphotericin B.11 We showed that a total lower dose can be used and with a shorter admission time because we used higher daily doses (3–5 mg/kg). The ideal dose of liposomal amphotericin B has not yet been established; a mean total dose of 2.500 mg or 35 mg/kg resulted in the healing of lesions in all patients independent of lesion severity, with no recurrences observed during the follow-up period. This reduced dose can be important to decrease costs. In Brazil, the price of 50 mg of the liposomal amphotericin is around US$200 and the total treatment would be from US$8,000 to US$12,000. However, the cost of antimonial is US$176.55 for the total treatment.3 Therefore, we believe that further studies are needed to confirm these findings in additional relevant populations.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Valdir Sabaga Amato, Division of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases, Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo, Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil, E-mail: valdirsa@netpoint.com.br. Felipe Francisco Tuon, Division of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases, Hospital Universitário Evangélico de Curitiba, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil, E-mail: flptuon@gmail.com. Raphael Abegão de Camargo, Department of Infectious Diseases University of São Paulo, Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil, E-mail: raphabegao@yahoo.com.br. Regina Maia Souza, Laboratório de Investigação Médica-Parasitologia, Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo, Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil, E-mail: regina-maia@uol.com.br. Carolina Rocio Santos, Department of Infectious Diseases University of São Paulo, Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil, E-mail: carolnet83@hotmail.com. Antonio Carlos Nicodemo, Department of Infectious Diseases University of São Paulo, Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil, E-mail: ac_nicodemo@uol.com.br.

References

- 1.Reithinger R, Dujardin J, Louzir H, Pirmez C, Alexander B, Brooker S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:581–596. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camargo RA, Tuon FF, Sumi DV, Gebrim EM, Imamura R, Nicodemo AC, Cerri GG, Amato VS. Mucosal leishmaniasis and abnormalities on computed tomographic scans of paranasal sinuses. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:515–518. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amato VS, Tuon FF, Siqueira AM, Nicodemo AC, Neto VA. Treatment of mucosal leishmaniasis in Latin America: systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:266–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nonata R, Sampaio R, Marsden PD. Mucosal leishmaniasis unresponsive to glucantime therapy successfully treated with AmBisome. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:77. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90404-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amato VS, Nicodemo AC, Amato JG, Boulos M, Neto VA. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis associated with HIV infection treated successfully with liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:341–342. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amato VS, Tuon FF, Imamura R, Abegão de Camargo R, Duarte MI, Neto VA. Mucosal leishmaniasis: description of case management approaches and analysis of risk factors for treatment failure in a cohort of 140 patients in Brazil. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1026–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bern C, Adler-Moore J, Berenguer J, Boelaert M, den Boer M, Davidson RN, Figueras C, Gradoni L, Kafetzis DA, Ritmeijer K, Rosenthal E, Royce C, Russo R, Sundar S, Alvar J. Liposomal amphotericin B for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:917–924. doi: 10.1086/507530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sundar S, Sinha PK, Rai M, Verma DK, Nawin K, Alam S, Chakravarty J, Vaillant M, Verma N, Pandey K, Kumari P, Lal CS, Arora R, Sharma B, Ellis S, Strub-Wourgaft N, Balasegaram M, Olliaro P, Das P, Modabber F. Comparison of short-course multidrug treatment with standard therapy for visceral leishmaniasis in India: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:477–486. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sundar S, Mehta H, Suresh AV, Singh SP, Rai M, Murray HW. Amphotericin B treatment for Indian visceral leishmaniasis: conventional versus lipid formulations. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:377–383. doi: 10.1086/380971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogelsinger H, Weiler S, Djanani A, Kountchev J, Bellmann-Weiler R, Wiedermann CJ, Bellmann R. Amphotericin B tissue distribution in autopsy material after treatment with liposomal amphotericin B and amphotericin B colloidal dispersion. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:1153–1160. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO . Control of the leishmaniasis: report of a meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on the Control of Leishmaniases. Geneva: 2010. pp. 22–26. March 2010. [Google Scholar]