Abstract

Health systems are often evaluated using indicators such as maternal mortality, which reflect the health status of the population and the effectiveness of health services. Addressing the right to health of persons with disabilities is a significant challenge for health systems because health services for this subgroup are interdependent on other sectors in society, such as education, employment and transportation. By considering health care access of persons with disabilities, it is possible to evaluate the overall effectiveness of the health system in terms of equity, accessibility and right to health.

The outcomes of certain health services can be used to assess the overall effectiveness of a health care system. For example, maternal mortality is an indicator of the quality of a country’s maternal health services, which in turn reflects the overall functioning of the country’s health system.1 We propose that access by persons with disabilities to health care services, along with measures of disability, constitutes an indicator of overall equity in a health care system. Disability is defined here as activity limitation arising from any one of a variety of conditions, such as spinal cord injury, diabetes or HIV/AIDS, and it can constitute a significant barrier to accessing health care. Transport to health care facilities may be inaccessible to persons with disabilities, and the educational opportunities and social welfare supports available to such individuals may not be sufficient to enable them to properly access the health care they need. The “system” that facilitates health for persons with disabilities thus reaches beyond the confines of health care facilities and the purview of health care professionals; indicators using this group of patients will therefore reflect the effectiveness of intersectoral and systemic contributors to equitable health care provision.

Disability and research for health

“All disabled people have the same needs for basic health services as anyone else. This is often denied.”2 With an estimated 650 million people living with disabilities in the world today and 2 billion family members directly affected by disability,3 the provision of health care for persons with disabilities represents a significant and largely overlooked challenge. However, it is now recognized that we cannot achieve the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals4 without addressing the health needs and rights of this group of people. Addressing the right to health of persons with disabilities will require an intersectoral response that addresses all of the determinants of health. Such a response is exactly what was sought in the Bamako call to action5issued at the conclusion of the 2008 Global Ministerial Forum on Research for Health in Mali. The insights we would derive from mounting this type of response for persons with disabilities would be useful in evaluating how other health needs are addressed.

In the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health,6 which was endorsed by all WHO member states at the 54th World Health Assembly in 2001, disability is defined as a degree of functional impairment(s) involving an organ or body part that may result in activity limitation(s), such as difficulties executing tasks or activities of daily living, and also in participation restrictions that hinder a person’s ability to play a meaningful role in society. This understanding of disability is much broader than the traditional idea of disability as a “handicap” that one either has or does not have, such as a loss of function resulting from an amputation or spinal cord injury; instead it incorporates many types of chronic illness as well as transitory conditions that impair functioning, limit activities or restrict participation. Everyone can therefore expect to experience some degree of disability at some point in their life.

Equity, disability and accessibility

Equity in health “implies that ideally everyone should have a fair opportunity to attain their full health potential and, more pragmatically, that none should be disadvantaged from achieving this potential, if it can be avoided.” (p. 433)7 Equity in health care implies “equal access to available care for equal need, equal utilization for equal need, equal quality of care for all.”(p. 424)7 A review of concepts and measurements of equity found the above definitions to be “clear and accessible to non-technical audiences, but lacking guidance on measurement.”(p. 173)8 If we are to use access to health care services by persons with disabilities as an indicator of equity in health care, we must have reliable and valid measures of both disability and access to health care.

International research projects such as Measuring Health and Disability in Europe9 and the Washington Group on Disability Statistics10 have improved techniques to measure disability. They have found that the continuum of activity limitations offers the most accurate scale to measure disability in self-report and observational studies.11-12 Measures developed by these initiatives are now being used in general household surveys and national censuses as well as in specialized health surveys.

Given that an all-encompassing tool to measure access to health care has yet to be developed, we propose using the conceptual framework offered by the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2000.13 That framework includes accessibility:“facilities, goods and services have to be accessible to everyone without discrimination within the jurisdiction of the state.”13 The committee identified four dimensions of accessibility: non-discrimination, physical accessibility, economic accessibility (affordability) and information accessibility.

Three additional elements of this committee’s statement also relate to the concept of accessibility.13 Availability concerns the quantity of service available; for example, functioning public health and health care facilities, goods, services and programs have to be available to the general public in sufficient quantity. Acceptability refers to the need for all health facilities, goods and services to be respectful of medical ethics, culturally appropriate, sensitive to gender and life-cycle issues and to be designed to respect confidentiality and improve the health status of those concerned. The final element is quality: health facilities, goods and services must be scientifically and medically appropriate to provide services of good quality.

Evaluating equity in health systems

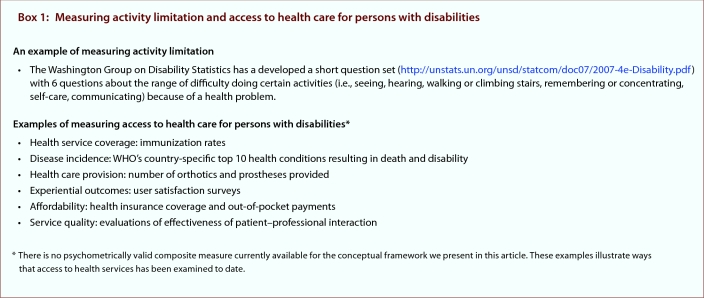

Evaluating health system accessibility and equity in responding to the right to health of all users, then, may best be done by evaluating the experiences of persons with disabilities. To do this we could take a sample population of persons with disabilities (e.g., people experiencing disability owing to chronic heart failure or diabetic peripheral neuropathy) and measure their activity limitations and access to health care (see Box 1). The data obtained from this sample could then be compared with data on the access to health care of people without activity limitations. In summary, although current indicators for health systems such as maternal mortality are useful, access to health care for people with activity limitation is an alternative indicator that would evaluate broader health system function, reflect the experiences of a wider population and involve intersectoral and systemic contributors to equitable health care.

Box 1.

Measuring activity limitation and access to health care for persons with disabilities

Biographies

Malcolm MacLachlan, PhD, is a professor at the Centre for Global Health and in the School of Psychology, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Hasheem Mannan, PhD, is a research fellow at the Centre for Global Health and in the School of Psychology, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin.

Eilish McAuliffe, PhD, is director of the Centre for Global Health and a senior lecturer in the School of Medicine, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding source: None.

Contributors: All three authors contributed substantially to the conception and drafting of the article, revised it critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. The first draft was written by Hasheem Mannan. Malcolm MacLachlan is the guarantor for the study.

References

- 1.Parkhurst Justin O, Danischevski Kirill, Balabanova Dina. International maternal health indicators and middle-income countries: Russia. BMJ. 2005 Sep 3;331(7515):510–513. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7515.510. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/16141161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Commission. Guidance note on disability and development for European Union delegations and services. Brussels: European Commission Directorate-General for Development; 2004. p. 6. http://ec.europa.eu/development/body/publications/docs/Disability_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fritz D, Rischewski D. What you need to know about: Disability and development cooperation - 10 facts or fallacies? Eschborn, Germany: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH; 2010. [accessed 2010 Dec 05]. http://www.gtz.de/de/dokumente/gtz2010-0477en-disability-development.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millennium Project. About MDGs: What they are. New York: United Nations; 2006. http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/goals/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Bamako call to action: research for health. Lancet. 2008 Nov 29;372(9653):1855. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: The Organization; 2001. [accessed 2008 Mar 28]. http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22(3):429–445. doi: 10.2190/986L-LHQ6-2VTE-YRRN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braveman Paula. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:167–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=16533114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brussels: European Commission; 2008. [accessed 2010 Dec 05]. MHADIE - Measuring Health and Disability in Europe. Policy recommendations. http://www.supportproject.eu/events/mhadie-measuring-health-and-disability-in-europe.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations Statistical Commission. Report of the Washington Group on Disability Statistics. Report no.: E/CN.3/2007/4. Geneva: United Nations Economic and Social Council; 2007. [accessed 2008 May 28]. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/doc07/2007-4e-Disability.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Center for Health Statistics. Washington Group on Disability Statistics. Hyattsville (MD): The Center; 2009. [accessed 2010 Oct 13]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/washington_group.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations Economic and Social Council. Report of the work session of the Budapest Initiative on measuring health status (Geneva, 20-22 January 2010). Report no.: ECE/CES/2010/46 (General Comments) Geneva: The Council; 2010. [accessed 2010 Dec 05]. [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations Economic and Social Council. The right to the highest attainable standard of health: 08/11/2000. Report no.: E/C.12/2000/4 (General Comments) Geneva: The Council; 2000. [accessed 2010 July 12]. http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/%28symbol%29/E.C.12.2000.4.En. [Google Scholar]