Academic Alternate Relationship Plans (AARPs) were implemented in the departments of medicine in the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry at the University of Alberta in 2002 and the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Calgary and Calgary Health Region in 2004. These plans, which compensate physicians on a contractual instead of a fee-for-service basis, have strengthened the ability of the two departments to deliver on their clinical, research and education missions. This commentary describes why and how they were developed.

To understand the context in which these AARPs were developed, recognition of the health care reform agenda in Canada and specifically in Alberta is required. Several national and provincial reports, including the Romanow,1 Kirby2 and Mazankowski3 reports, suggested the need to reframe and refocus the health care system to ensure access, quality and sustainability. These reports all recommended that alternative mechanisms be considered for physician remuneration in an effort to encourage innovative health care delivery. The Mazankowski report,3 which resulted from a review of Alberta’s health system, not only recommended alternative approaches for physician remuneration but also set specific targets. The Auditor General of Alberta, in consecutive annual reports4-7 (1998–2002), highlighted several issues: physicians needed to reduce their reliance on fee-for-service income to support their work in medical education and research; stakeholders in the health care system needed to understand that the scope of the work conducted by physicians in academic medicine went beyond seeing patients (the only work for which they were remunerated at the time); and inequities in physician remuneration in academic centres needed to be addressed.

Before the inception of the AARPs in Calgary and Edmonton, the two departments of medicine were experiencing similar challenges, many of which were common across Canada: the province’s population was growing significantly, the population was aging, demand for specialist services was increasing, there were substantially fewer physicians in the workforce than needed (a situation that was projected to continue), physicians were burning out, the demand for medical education was increasing, innovative care models needed to be developed to meet public expectations, and fee-for-service clinical earnings had increased significantly during the 1990s, which made it difficult to recruit academic physicians.8-10

The growth rates of the metropolitan populations of Calgary and Edmonton were among the highest in Canada during the late 1990s and at the beginning of the new decade. Approximately 40%–50% of the new residents were foreign immigrants, creating challenges with respect to language barriers and complex health and social problems. A survey of Albertans in 2003 reported significant concerns regarding specialist access, with only 38% of respondents reporting having easy access to specialist services.10 Both departments already had far fewer physicians than they needed, and the situation was expected to get worse with the projected retirements of senior faculty members. In Calgary, a time-motion study revealed that the average department member was working at a 1.20 full-time equivalent (FTE), excluding on-call hours, and many were working well above this level.8 Furthermore, significantly more women were expected to qualify as new medical specialist physicians than in the past, which was expected to add to the workforce deficit. The FTE model proposed by the Physician Resource Planning Committee of the Alberta Medical Association and Alberta Health and Wellness used a work-week discount factor of 0.81 for female physicians, assuming that female physicians would work fewer hours per week than male physicians, that many of them would take maternity leaves and that they would shift away from heavy clinical loads earlier in their careers than their male counterparts.8 There were serious concerns about physician burnout, which were not unique to Alberta.8 A planned increase in the undergraduate class size in both Alberta medical schools was expected to increase the teaching needs at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

The department of medicine at the University of Alberta had a practice plan in place before the adoption of the AARP that allocated clinical payments in a way that was intended to allow academic physicians to focus more on their department’s academic mission. However, increasing demands on the practice plan’s participants for clinical work were hindering the ability of the practice plan to fulfil this intention. The plan found itself with an increasing debt burden and the department found itself with an inability to recruit academic physicians. An AARP was expected to break with the model of incentives and disincentives prevalent in the traditional fee-for-service system and instead provide a mechanism that would reward physicians for innovative practice patterns independent of patient volume and provide incentives for greater use of interdisciplinary and preventive approaches to improving overall population health.

The process used to develop the AARP was based on a framework established within Alberta Health and Wellness, which included the preparation of a letter of intent, a full proposal, a service delivery plan, governance and accountability measures, a budget and workforce plans. The initial agreement in Edmonton included a services agreement between the regional health authority and participating physicians; a grant agreement between the faculty and the provincial ministries of advanced education and learning and health and wellness that included expected outcomes, performance measures and targets; and the actual alternative payment plan. An agreement also had to be reached with the Alberta Medical Association. After 2003 the AARP process evolved with the establishment of the tri-lateral agreement between the respective health authorities, the Alberta Medical Association and Alberta Health and Wellness, but the core elements were retained.11 The AARP agreement, which commenced in August 2004 in Calgary, followed the new process.

The leaders and individual members of the divisions within the departments of medicine at the two universities had to do considerable work once the agreement was reached. Communication about the AARP was key, as participation in the plan was voluntary. The leaders of each division established objectives for their division and circulated them to their members. These included developing and implementing innovative models of health care delivery, designing new practice patterns, improving recruitment and retention, improving the national competitiveness of the division, ensuring that the division and its members were fully engaged in educational activities, enhancing opportunities for medical research, fostering the ability of division members to assume leadership roles, ensuring that remuneration was adequate and ensuring that workloads within the division were fair and equitable. Stakeholders—Alberta Health and Wellness, the Alberta Medical Association, Alberta Advanced Education and Technology, the faculties of medicine at the two universities and the regional health authorities—expected results consistent with the goals of the AARP: adequate physician complements, innovative care delivery, improved access to medical specialists, delivery of high-quality care, delivery of high-quality education to health care learners, greater research capacity, demonstration of effective governance and accountability.

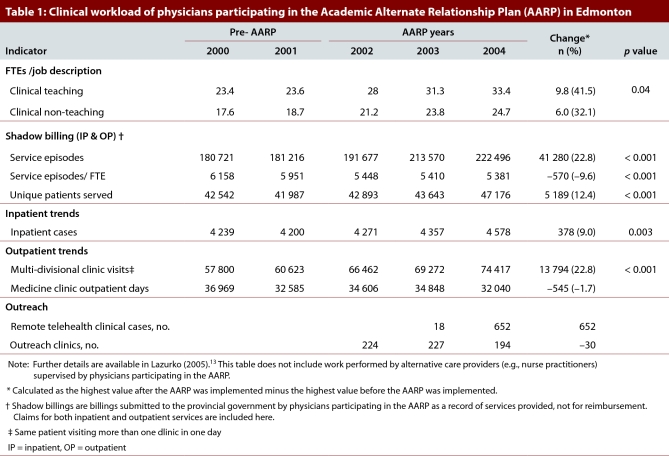

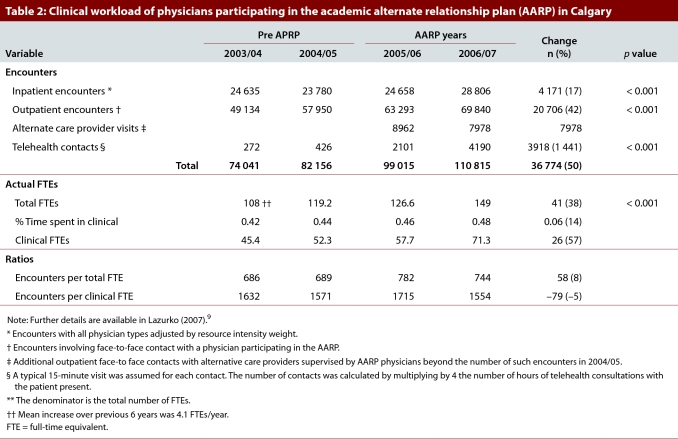

Data collected from multiple sources in both Edmonton and Calgary before and after the implementation of the AARP were evaluated by the same external evaluator using the same methodology each time. This before–after analysis was completed using specific indicators in each CARE pillar: clinical care, administration, research and education.12,13 Descriptive epidemiologic analysis was conducted and comparisons of observed and expected events were analyzed using a Poisson distribution, with a p value < 0.05 considered significant. In Edmonton, access to specialist services improved: clinical full-time equivalents increased by 35%, from 30.5 in 2001 to 41.4 in 2004, and clinical service volume increased by 23% (calculated from data shown in Table 1). In Calgary, clinical workload (patient encounters), including outpatient contacts with alternative care providers and telehealth contacts, increased by 50% (Table 2). A survey of 135 physicians12 revealed that 63%, 64% and 56% of physicians in Calgary felt that the AARP had had a positive effect on their ability to spend more time with patients with complex needs, implement innovations and provide interdisciplinary care, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical workload of physicians participating in the Academic Alternate Relationship Plan (AARP) in Edmonton

Table 2.

Clinical workload of physicians participating in the academic alternate relationship plan (AARP) in Calgary

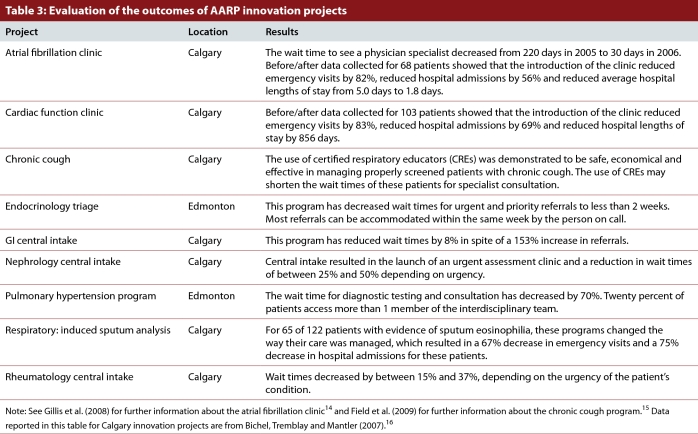

Separate innovation funding led to enhanced linkages with primary care physicians, the development of central referral and triage processes, support for interdisciplinary models of care, the application of clinical practice guidelines and the creation of new specialty clinics (Table 3).14-16 Recruitment increases (Tables 1 and 2) of 31.1% and 38% respectively for Edmonton and Calgary were significantly higher than the increases of 1%–5% in Edmonton and 4.3% in Calgary per annum in the 6 years preceding the implementation of the AARP. Combined teaching hours in Edmonton and Calgary increased by 22% and 25%, respectively, after the AARP was implemented. Research performance also improved: in Edmonton, the number of research FTEs in Edmonton increased by 39% and the percentage of their time that department members dedicated to research increased from 15% in 2003 to 21% in 2006 (Table 1).

Table 3.

Evaluation of the outcomes of AARP innovation projects

Implementation of an AARP is complex, and we acknowledge that in other settings, individual parameters and context for implementation are important considerations. Evaluation of an AARP is complicated, and we acknowledge the limitations and intrinsic bias of the before–after methodology we used. The AARP was implemented in Edmonton and Calgary during an economic boom in Alberta, and some of the positive effects of the AARP that we noted may have been related to the province’s robust economic growth. However, there are relatively few studies in Canada examining the effect of physician remuneration models on the efficiency and quality of care in academic centres. The Queen’s University alternative funding plan, which was established in 1994, has been assessed with a survey of the perceptions of referring physicians and specialists17 and with a before–after analysis in that university’s department of family medicine.18 The perception survey revealed mixed results, but the before–after analysis demonstrated that after the alternative funding plan was implemented academic productivity improved, practice volume decreased by 10% and patient flow improved. In Nova Scotia, a recently completed audit of the alternative funding plan in the department of medicine at Dalhousie University suggested that it helped recruitment and retention and enhanced patient care.19 Our analysis adds more robust results to this body of literature.

In Edmonton and Calgary, the introduction of an alternative funding plan significantly enhanced recruitment and clinical volumes, improved patient access to specialist services and helped the departments of medicine to fulfill their teaching and research missions. We believe that the introduction of AARPs has been the single largest contributor to the academic and clinical success of our departments and has been a major lever for health care transformation in our setting.

Biographies

Affiliations at the time of submission: Allison Bichel, MPH MBA, was project manager for Innovation Initiatives in the Department of Medicine, Calgary Health Region, and University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Maria Bacchus, MD, was vice chair of the Department of Medicine, Calgary Health Region, and University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Jon Meddings, MD, was chairman of the Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.

John Conly, MD, was chairman of the Department of Medicine, Calgary Health Region, and University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding source: This work was funded in part by the departments of medicine at the University of Calgary and University of Alberta.

Contributors: Allison Bichel, as a consultant to the Calgary Health Region, was responsible for the implementation of the health service innovations for the academic alternate relationship plan in the Department of Medicine in Calgary, for the design and implementation of the evaluation of the innovations in Calgary and for preliminary collation of the data for this article. John Conly, Maria Bacchus and Jon Meddings conceived of this article, arranged for the full evaluation data of the academic alternate relationship plans from their respective sites to be obtained from Alberta Health and Wellness and act as guarantors for this article. Allison Bichel drafted the initial manuscript. All of the authors reviewed and revised the manuscript for critical content and approved the final version to be published.

References

- 1.Romanow R J. Building on values: the future of health care in Canada. Saskatoon: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. [accessed 2010 Nov 22]. http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/Collection/CP32-85-2002E.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirby M J L. The health of Canadians: the federal role. Volume 6: Recommendations for reform. Ottawa: Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology; 2002. [Accessed 2010 Sept 02]. http://www.parl.gc.ca/37/2/parlbus/commbus/senate/Com-e/soci-e/rep-e/repoct02vol6-e.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazankowski D. A framework for reform: report of the Premier’s Advisory Council on Health. Edmonton: Government of Alberta; 2001. [accessed 2010 Sept 02]. http://www.health.alberta.ca/documents/Mazankowski-Report-2001.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valentine P. Annual report of the Auditor General of Alberta 1998–99. Edmonton: Government of Alberta; 1999. [accessed 2010 Sept 02]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valentine P. Annual report of the Auditor General of Alberta 1999–2000. Edmonton: Government of Alberta; 2000. [accessed 2010 Sept 02]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valentine P. Annual report of the Auditor General of Alberta 2000–2001. Edmonton: Government of Alberta; 2001. [accessed 2010 Sept 02]. http://www.oag.ab.ca/files/oag/ar2000-01.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn FJ. Annual report of the Auditor General of Alberta 2001–2002. Edmonton: Government of Alberta; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Medicine, Alberta Health Services. Proposal for an alternate funding plan. Calgary: Calgary Health Region; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Medicine, Alberta Health Services. Physician resource planning working group. Key findings and recommendations. Calgary: Calgary Health Region; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health Services Utilization and Outcomes Commission. Health services satisfaction: survey of Albertans 2003. Calgary: 2003. [accessed 2010 Sept 02]. p. 3. http://www.assembly.ab.ca/lao/library/egovdocs/alhsuo/2003/142772.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alberta Health and Wellness. Academic alternate relationship plans. [accessed 2010 Sept 02]. http://www.health.alberta.ca/professionals/ARP-Academic.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazurko M. Final evaluation report. Academic alternate relationship plan. Calgary: Department of Medicine, University of Calgary and Calgary Health Region, Department of Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazurko M. Final evaluation report. Alternate funding plan. Edmonton: Department of Medicine, University of Alberta; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillis Anne M, Burland Laurie, Arnburg Beverly, Kmet Cheryl, Pollak P T, Kavanagh Katherine, Veenhuyzen George, Wyse D G. Treating the right patient at the right time: an innovative approach to the management of atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24(3):195–198. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70583-x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/18340388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Field S K, Conley D P, Thawer A M, Leigh R, Cowie R L. Assessment and management of patients with chronic cough by a certified respiratory educator. A randomized controlled trial. Can Respir J. 2009;16(2):49–54. doi: 10.1155/2009/263054. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/19399308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bichel A, Tremblay A, Mantler E. Department of Medicine and Medical Services alternative relationship plan innovation initiatives. Final evaluation report. Calgary: Calgary Health Region; 2007. [accessed 2011 Feb 2]. http://www.departmentofmedicine.com/d_medicine/pages/news%20files/Innovation%20Report%202007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godwin M, Shortt S, McIntosh L, Bolton C. Physicians’ perceptions of the effect on clinical services of an alternative funding plan at an academic health sciences centre. CMAJ. 1999;160(12):1710–1714. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/10410632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godwin M, Seguin R, Wilson R. Queen’s University alternative funding plan. Effect on patients, staff, and faculty in the Department of Family Medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2000;46:1438–1444. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/10925758. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.North South Group Inc. Audit of the Department of Medicine alternative funding arrangement. Halifax: Nova Scotia of Health Physician Services; 2005. [accessed 2010 Nov 23]. http://www.gov.ns.ca/health/reports/pubs/Alternate_Funding_Audit_2004.pdf. [Google Scholar]