Abstract

Background

Bodychecking is a leading cause of injury among minor hockey players. Its value has been the subject of heated debate since Hockey Canada introduced bodychecking for competitive players as young as 9 years in the 1998/1999 season. Our goal was to determine whether lowering the legal age of bodychecking from 11 to 9 years affected the numbers of all hockey-related injuries and of those specifically related to bodychecking among minor hockey players in Ontario.

Methods

In this retrospective study, we evaluated data collected through the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program. The study’s participants were male hockey league players aged 6–17 years who visited the emergency departments of 5 hospitals in Ontario for hockey-related injuries during 10 hockey seasons (September 1994 to May 2004). Injuries were classified as bodychecking-related or non-bodychecking-related. Injuries that occurred after the rule change took effect were compared with those that occurred before the rule’s introduction.

Results

During the study period, a total of 8552 hockey-related injuries were reported, 4460 (52.2%) of which were attributable to bodychecking. The odds ratio (OR) of a visit to the emergency department because of a bodychecking-related injury increased after the rule change (OR 1.26, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.16–1.38), the head and neck (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.26–1.84) and the shoulder and arm (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.04–1.35) being the body parts with the most substantial increases in injury rate. The OR of an emergency visit because of concussion increased significantly in the Atom division after the rule change, which allowed bodychecking in the Atom division. After the rule change, the odds of a bodychecking-related injury was significantly higher in the Atom division (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.70–2.84).

Interpretation

In this study, the odds of injury increased with decreasing age of exposure to bodychecking. These findings add to the growing evidence that bodychecking holds greater risk than benefit for youth and support widespread calls to ban this practice.

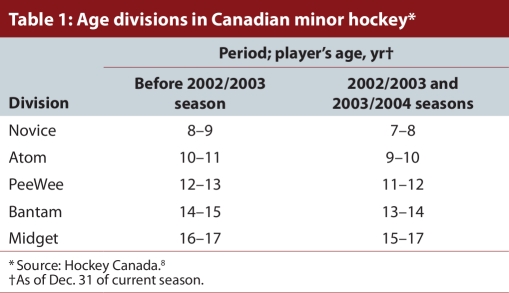

Bodychecking is the most common cause of all ice hockey injuries. The practice has raised particular concern because it can lead to severe injuries such as fractures and traumatic brain injury.1-5 Unfortunately, bodychecks from behind, which send players headfirst into the boards, are still a frequent cause of injury, despite rules prohibiting this practice.3 The debate about the value of bodychecking for Canadian minor hockey players has increased since the 1998/1999 hockey season, when Hockey Canada introduced a 5-year voluntary pilot program that lowered the legal age for body contact from 12 and 13 years (PeeWee division6) to 10 and 11 years (Atom division7) (see Table 1 for Hockey Canada’s age divisions over the period of this study). Proponents of the rule change have argued that lowering the age limit for body contact enables minor hockey players to learn how to properly receive and give a bodycheck at an earlier age and that this early learning and repeated reinforcement of proper technique would reduce injuries at older ages. In 2005, Hockey Canada approved continuation of the pilot program beyond the initially planned 5-year period. By that time, the age categories had also been changed, and the youngest players in the Atom division were 9 years old (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Age divisions in Canadian minor hockey

The purpose of this study was to examine available data on injuries among competitive minor hockey players in Ontario to determine whether there has been any change in the rate of bodychecking injuries since the legal age for body contact was lowered in 1998/1999. We also examined whether available data support the claim that allowing body contact at an early age (i.e., in the Atom Division) reduces bodychecking injuries at older ages (i.e., in PeeWee, Bantam and Midget divisions).

Methods

This study is based on data from 5 Ontario hospitals that participate in the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (CHIRPP). We used data from 3 pediatric hospitals (The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa and the Children’s Hospital of Western Ontario in London) and 2 general hospitals (Kingston General Hospital and Hotel Dieu Hospital, both in Kingston). CHIRPP is a national surveillance system that collects data on injuries of people who visit the emergency departments of 14 hospitals across Canada. The information collected consisted of what the injured person was doing at the time of the injury, the cause of the injury, the factors contributing to the injury, the time and place of the injury and the patients’ age and sex.9 Although only selected hospitals report to CHIRPP, previous authors have reported that the data collected through the program represent general injury patterns among Canadian youth.10,11

We included in the study male patients between the ages of 6 and 17 years who visited an emergency department because of a hockey-related injury between September 1994 and May 2004 (10 hockey seasons). We excluded female patients because Hockey Canada’s rule change related to bodychecking was limited to minor hockey leagues for boys. We also excluded patients from the province of Quebec who visited the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (by checking the residence postal codes of patients at this hospital).

Narrative descriptions of injuries are captured in the CHIRPP database under the variable “What happened?” We used these descriptions to identify hockey-related injuries and to classify injuries as being related or not related to bodychecking, according to the automated methodology developed by McFaull.2 For narratives containing the term “check,” “checked,” “cross checked,” “pushed from behind,” “hit from behind,” “was hit by other/another player,” “got hit by other/another player,” “hit against boards,” “hit into boards,” “hit by elbow,” “elbowed,” “hit by knee,” “kneed,” “body contact,” “mis en échec,” “heurté,” and “plaqué,” we classified the injury as being related to bodychecking; all other injuries were grouped as non-bodychecking injuries.

We excluded injuries for which the narrative contained the term “collision between players” or “collided with a player” because we believed that such injuries might or might not relate to bodychecking, and the information contained in the narratives was insufficient to conclusively determine whether the injuries had occurred as a result of bodychecking or other mechanisms.

To assess the potential for misclassification by the automated system that we used to classify bodychecking and non-bodychecking injuries, a 10% random sample of the data for hockey-related injuries was manually coded, and the level of agreement between manual and automated coding was determined.

We classified players, on the basis of age and the date of injury, into specific divisions of Hockey Canada (The Canadian Hockey Association became Hockey Canada). The association changed its age categorization for minor league divisions in the 2002/2003 season.8 Therefore, for the last 2 seasons under consideration in this study (2002/2003 and 2003/2004), we classified players according to the new groupings (Table 1).

Most minor hockey leagues in Ontario implemented the pilot program that lowered the legal age for body contact during the 1998/1999 season. The Ottawa District Minor Hockey League and the Kingston Area Minor Hockey Association joined the program during the 2001/2002 hockey season. Accordingly, if the injured player presented to any of the 5 Ontario hospitals between the 1994/1995 and 1997/1998 hockey seasons or presented to the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, the Kingston General Hospital or the Hotel Dieu Hospital of Kingston between the 1998/1999 and 2000/2001 hockey seasons, the injury was categorized as having occurred before the rule change. If the injured player presented to The Hospital for Sick Children or the Children’s Hospital of Western Ontario after the 1998/99 hockey season or presented to the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, the Kingston General Hospital or the Hotel Dieu Hospital between the 2001/2002 and 2003/2004 hockey seasons, the injury was classified as having occurred after the rule change.

We compared visits to the emergency department by minor hockey league players for bodychecking injuries (i.e., hockey-related injuries attributed to bodychecking) and non-bodychecking injuries (i.e., hockey-related injuries resulting from mechanisms other than bodychecking). We calculated the odds of sustaining a bodychecking injury as the proportion of emergency department visits for hockey-related injuries that were due to bodychecking after the rule change divided by the proportion of visits for hockey-related injuries due to bodychecking before the rule change.

The St. Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board approved this study. Statistical analyses were performed with the SAS 8.0 system (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, N.C.). We used Mantel-Haenszel χ2 statistics to calculate the odds ratios (ORs), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for sustaining bodychecking injuries relative to non-bodychecking injuries.

Results

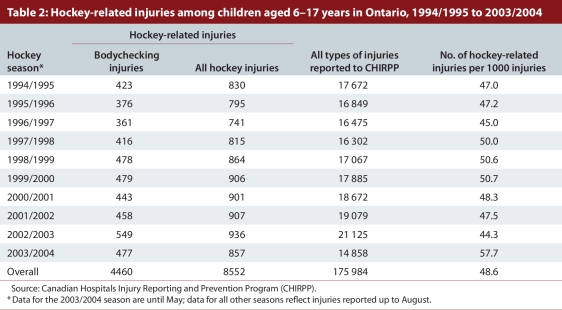

Our analysis of the CHIRPP data revealed 9043 hockey-related injuries among children aged 6 to 17 years. We excluded 491 of these injuries because the narratives contained the terms “collision between players” or “collided with a player,” and we could not determine if they were related to bodychecking or some other mechanism. The remaining 8552 hockey-related injuries represented 4.9% of the 175 984 injuries (including the 491 excluded injuries) for this age group in the CHIRPP or 48.6 hockey-related injuries per 1000 injuries of all types (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hockey-related injuries among children aged 6–17 years in Ontario, 1994/1995 to 2003/2004

Manual coding of a 10% random sample of the hockey-related injuries (n = 855) revealed that the automated system misclassified only 30 (3.5%) of the injuries. The level of agreement between automated and manual coding was excellent (α = 0.93, p < 0.001).

More than half of all hockey-related injuries (4460 or 52.2%) reported through CHIRPP by the study hospitals during the study period were related to bodychecking. The number of bodychecking injuries fluctuated over the study period, in a pattern similar to that for all hockey-related injuries (Table 2). Because of a lack of data on the number of minor hockey players in each season, we could not determine whether an increase in the number of hockey-related injuries (and corresponding increases in bodychecking injuries) was due to an increase in the number of players, an increase in the rate of injuries or both.

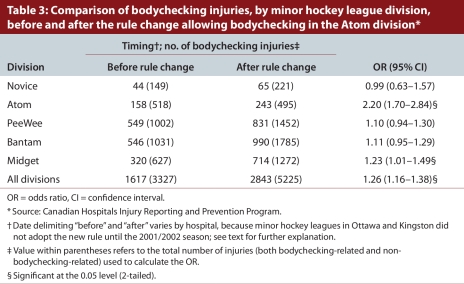

Overall, the odds of sustaining a bodychecking injury increased after the rule change in all divisions of the various minor hockey leagues (except in the Novice division, in which body contact is not allowed) relative to the period preceding the rule change (Table 3). The rule change had the greatest effect in the Atom division. For that division, representing the youngest age group in which bodychecking was allowed after the rule change, there was a significant increase in the odds of an emergency department visit due to a bodychecking injury (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.70–2.84).

Table 3.

Comparison of bodychecking injuries, by minor hockey league division, before and after the rule change allowing bodychecking in the Atom division

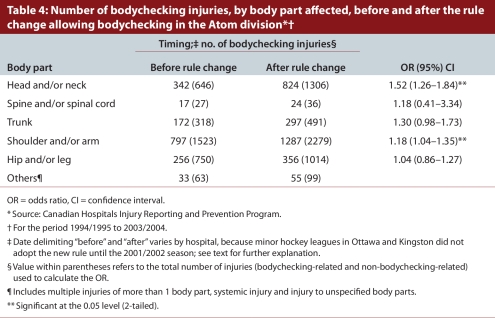

The body parts most often affected as a result of bodychecking injuries were the shoulders and/or arms, followed by the head and/or neck and the hip and/or leg (Table 4). The odds of an emergency department visit because of an injury to the head or neck related to bodychecking increased significantly (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.26–1.84) after the legal age for bodychecking was reduced.

Table 4.

Number of bodychecking injuries, by body part affected, before and after the rule change allowing bodychecking in the Atom division

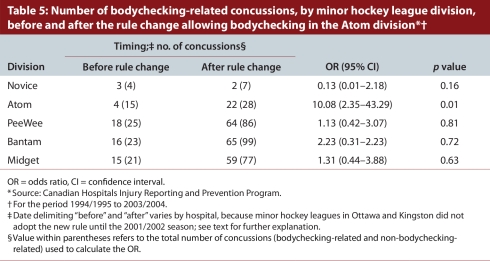

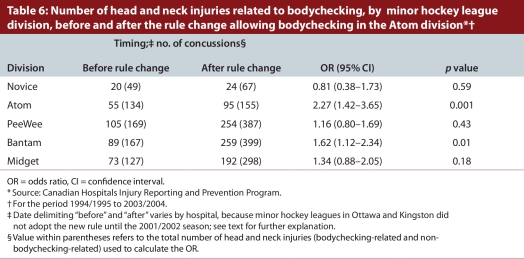

We also analyzed the odds of an emergency department visit due to bodychecking after the rule change relative to before the rule change for concussions and head and neck injuries. The odds of a visit to the emergency department due to concussion increased significantly after the rule change within the Atom division, for which bodychecking was not allowed before the rule change but was allowed after the rule change (OR 10.08, 95% CI 2.35–43.29) (Table 5). Similarly, the odds of a visit to the emergency department due to a head or neck injury increased significantly after the rule change in both the Atom division (OR 2.27, 95% CI 1.42–3.65) and the Bantam division (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.12–2.34) divisions (Table 6).

Table 5.

Number of bodychecking-related concussions, by minor hockey league division, before and after the rule change allowing bodychecking in the Atom division

Table 6.

Number of head and neck injuries related to bodychecking, by minor hockey league division, before and after the rule change allowing bodychecking in the Atom division

Interpretation

In this study, more than half of the hockey-related injuries leading to visits to the emergency department were attributable to bodychecking. Players in the division affected by the change in rules that allowed bodychecking at a younger age (the Atom division) sustained a significantly higher number of bodychecking-related injuries after the rule change. The proportion of bodychecking injuries relative to non-bodychecking injuries also increased slightly among players in the PeeWee, Bantam and Midget divisions (Table 3).

In a previous study,12 the odds of bodychecking injuries among hockey players 10 to 13 years of age were higher in Ontario (where bodychecking was introduced at a younger age) than Quebec, which indicates that there was no protective effect from learning to bodycheck earlier. Although Macpherson and colleagues12 also used the CHIRPP database, their focus was on injuries that occurred between 1995 and 2002, whereas we analyzed the period before and after the rule change (that is, 1994 to 2004), and we focused solely on Ontario.

The authors of another study13 found a 2-fold increase in the rate of injuries among 11-year-old children who initially played at the Atom level (where bodychecking was not allowed) but were subsequently moved to the PeeWee division (where bodychecking was allowed) after the change in age classification implemented by Hockey Canada for the 2002/2003 season (see Table 1). Similarly, after a 3-year longitudinal study examining injury rates among Atom players in the Ottawa District Hockey Association (where bodychecking was prohibited) and in minor leagues within the Ontario Hockey Federation (where bodychecking was allowed), Montelpare and colleagues14 reported that the proportion of checking-related injuries in the leagues that allowed checking was 3 times greater than in the league that did not allow checking.

Willer and colleagues15 found that hockey leagues that allowed bodychecking for all players between 9 and 14 years of age had higher rates of injury than leagues that did not allow bodychecking. Despite these results, the authors stated that bodychecking should be introduced at an earlier age, attributing their results to a speculated increase in testosterone and aggression at these ages. Dryden and colleagues16 calculated rate ratios (bodychecking v. non-bodychecking) in each age group in the study by Willer and colleagues,15 comparing the bodychecking and non-bodychecking teams. Their analysis showed that, for all age groups, the leagues that allowed bodychecking always had higher rates of injury. The rate ratios ranged from 2 to 10, clearly demonstrating that bodychecking increased the odds of injury for every age group.16 From these studies, it is clear that learning to bodycheck at a younger age does not reduce a player’s odds of injury; instead, it prolongs the exposure to risk.

In our study, we found that the odds of head and brain injuries (including concussion) increased significantly after the legal age for body contact was reduced. Furthermore, the odds of trauma to the head and brain increased as soon as children were exposed to bodychecking (i.e., in the Atom division) and did not decline in the older age divisions.

The strong relation between bodychecking and the occurrence of concussions suggested by these results is consistent with the results of a study by Emery and Meeuwisse,1 who examined the mechanisms and types of injury sustained by players in a Canadian minor hockey league. Those authors found that bodychecking was the primary mechanism of injury in age divisions that allowed checking, and concussion was the most prevalent type of injury.1 These results heighten concerns about bodychecking, because concussions have been shown to cause impairments in information processing and cognition, postconcussion syndrome17-19 and neuropsychological deficits. Furthermore, multiple concussions have a cumulative detrimental effect.20-22 Such traumatic brain injuries should be a priority concern for players, parents, league administrators and others involved in the sport.

There is no evidence that changes in other aspects of the game (e.g., equipment use or training regimens) during the study period contributed to the increase in injury rate observed since the change in the bodychecking rule. Unfortunately, the head and neck are the most susceptible sites for increased injury. Although Hockey Canada has reversed the earlier change, and bodychecking is now allowed only in the PeeWee, Bantam and Midget divisions,23 thousands of children are still needlessly exposed to the risk of potentially serious injury, especially repeated brain injury.

Limitations

This study was based on injury data for players who visited emergency departments of hospitals participating in the CHIRPP surveillance program and did not include players who visited hospitals not participating in this program or those who sought medical care in physicians’ offices or clinics. The CHIRPP data set captured only relatively severe injuries requiring hospital treatment, and use of this data source might have limited the number of minor injuries included in the analysis. The large sample size and the study design allowed us to calculate odds ratios; however, the total number of minor hockey players each year was not available, and hence we could not calculate injury rates.

Another limitation of using the CHIRRP data set is that we did not know the specific age divisions and competitive levels of the players; we based our categorization solely on patients’ ages. In addition, we could not determine whether players had been injured in non-league play, such as high school games. However, other studies have shown that the risks in competitive play are higher than those in less competitive environments.4 We may also have undercounted the number of injuries related to bodychecking because we categorized an injury as being related to bodychecking only if the narrative text in the database explicitly indicated that bodychecking had been involved. Some injuries in the database might have resulted from a bodycheck, but the narrative description might have focused on another aspect of the injury (for example, “injured arm after sliding into the boards”).

Implications

Ultimately, the issue of bodychecking in ice hockey needs to be resolved by a weighing of the risks and benefits of the practice by all those with a stake in ice hockey and in the health of children and youth. There is now a substantial consensus, based on a multitude of research studies, that bodychecking increases the number of injuries. In particular, the incidence of concussion and other injuries increases consistently with increase in exposure to bodychecking, reaching its zenith at the elite levels of collegiate leagues and the National Hockey League.24-26 Bodychecking is also clearly associated with significant risks of fracture27-29 and spinal injury.30

Despite the growing evidence of the detrimental effects of bodychecking, there is no evidence to indicate that earlier exposure to bodychecking and earlier learning about how to give and receive a bodycheck lowers subsequent odds of injury in hockey.

Several years ago, 14 governmental jurisdictions in Canada established a Canadian sport policy, with the intent of having Canadians of all ages participate in sport.31 The policy describes sport as “a powerful vehicle for the enhancement of health, well-being, and community development.”31 In Canada, hockey is a sport with great potential to increase the health of individuals; however, it is clear that the risks of bodychecking far outweigh any potential benefits.

Conclusion

In our study, the odds of injuries, especially injuries to the head and brain, increased when bodychecking was allowed among younger players. The increased odds were noted in the first year of exposure to bodychecking and were sustained during all subsequent years. Players not exposed to bodychecking did not show any changes in rates of injury over time.

This study has contributed to the extensive evidence base that bodychecking causes substantial risks of all types of injuries, especially injuries to the head and brain. Although bodychecking can have the effect of intimidating those who receive the bodycheck, there is no evidence that this has any beneficial effect for any player, team, organization or for the sport. Stakeholders such as hockey organizations, insurers, sponsors, the media, parents and players should commit to multifaceted approaches to reduce the risks of injury in ice hockey. In addition to eliminating bodychecking from the sport 4 and changing the rules of the game, educational, legal and financial approaches ought to be introduced to reduce the risk of injury and to correct those factors that contribute to risk and attrition from the sport.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Public Health Agency of Canada for providing access to the study data.

Biographies

Michael D Cusimano, MD, PhD, FRCSC, is a neurosurgeon with the Division of Neurosurgery and director of the Injury Prevention Office, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont., Canada. Dr. Cusimano leads the Canadian Research Team in Traumatic Brain Injury and Violence.

Nathan A Taback, PhD, is an assistant professor of Biostatistics at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto.

Steven R McFaull, MSc, is a research analyst at the Centre for Healthy Human Development at the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Ryan Hodgins, MD, is a medical resident at the University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Tsegaye M Bekele, MPH, is a research analyst at the Ontario HIV Network.

Nada Elfeki, MSc, is a Research Coordinator with the Injury Prevention Research Office at St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Michael Cusimano is a volunteer vice-president of the Think First Foundation of Canada, a non-profit organization dedicated to the prevention of brain and spinal cord injury.

Funding source: Michael Cusimano receives research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and not of the Think First Foundation of Canada or the CIHR.

Contributors: All co-authors were involved in drafting the article. Nathan Taback, Tsegaye Bekele, Steven McFaull and Ryan Hodgins conducted the analyses. Micheal Cusimano is the guarantor.

References

- 1.Emery Carolyn A, Meeuwisse Willem H. Injury rates, risk factors, and mechanisms of injury in minor hockey. Am J Sports Med. 2006 Jul 21;34(12):1960–1969. doi: 10.1177/0363546506290061. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=16861577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McFaull S. Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (CHIRPP) News. 19. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2001. Jan, Contact injuries in minor hockey: A review of the CHIRPP Database for the 1998/1999 hockey season. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tator C H, Carson J D, Cushman R. Hockey injuries of the spine in Canada, 1966-1996. CMAJ. 2000 Mar 21;162(6):787–788. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/10750464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marchie Anthony, Cusimano Michael D. Bodychecking and concussions in ice hockey: Should our youth pay the price? CMAJ. 2003 Jul 22;169(2):124–128. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/12874161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hostetler S, Xiang H, Smith G. Characteristics of ice hockey-related injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2001–2002. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):661–666. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1565. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15574599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hockey Canada. Player Development: Pee Wee. [accessed 2008 Jan 30]. http://www.hockeycanada.ca/index.php/ci_id/7655/la_id/1.htm.

- 7.Hockey Canada. Player Development: Atom. [accessed 2008 Jan 28]. http://www.hockeycanada.ca/index.php/ci_id/7535/la_id/1.htm.

- 8.Hockey Canada. Player Development. [accessed 2008 Aug 10]. http://www.hockeycanada.ca/index.php/ci_id/7534/la_id/1.htm.

- 9.Public Health Agency of Canada. What is CHIRPP? [accessed 2007 July 12]. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/injury-bles/chirpp/index.html.

- 10.Pickett W, Brison R J, Mackenzie S G, Garner M, King M A, Greenberg T L, Boyce W F. Youth injury data in the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program: do they represent the Canadian experience? Inj Prev. 2000;6(1):9–15. doi: 10.1136/ip.6.1.9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/10728534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackenzie S G, Pless I B. CHIRPP: Canada’s principal injury surveillance program. Inj Prev. 1999;5(3):208–213. doi: 10.1136/ip.5.3.208. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/10518269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macpherson A, Rothman L, Howard A. Body-checking rules and childhood injuries in ice hockey. J Ped. 2006;117(2):143–147. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagel Brent E, Marko Josh, Dryden Donna, Couperthwaite Amy B, Sommerfeldt Joseph, Rowe Brian H. Effect of bodychecking on injury rates among minor ice hockey players. CMAJ. 2006 Jul 18;175(2):155–160. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051531. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/16847275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montelpare W, McPherson N. Measuring the effects of initiating body checking at the Atom age level. J ASTM Int. 2004;1(2):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willer B, Kroetsch B, Darling S, Hutson A, Leffy J. Injury rates in house league select, and representative youth ice hockey. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(10):1658–1663. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000181839.86170.06. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=16260964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dryden Donna M, Rowe Brian H, Hagel Brent E, Marko Josh. Body checking in youth hockey is dangerous. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(4):799. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000210152.83076.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cantu R C. Cerebral concussion in sport: management and prevention. Sports Med. 1992;14(1):64–74. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199214010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grindel Scott H. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of minor traumatic brain injury. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2003;2(1):18–23. doi: 10.1249/00149619-200302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCrea Michael, Kelly James P, Randolph Christopher, Cisler Ron, Berger Lisa. Immediate neurocognitive effects of concussion. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(5):1032–1040. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200205000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantu R C. Second-impact syndrome. Clin Sports Med. 1998;17(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins Michael W, Lovell Mark R, Iverson Grant L, Cantu Robert C, Maroon Joseph C, Field Melvin. Cumulative effects of concussion in high school athletes. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(5):1175–1179. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200211000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaetz M, Goodman D, Weinberg H. Electrophysiological evidence for the cumulative effects of concussion. Brain Inj. 2000;14(12):1077–1088. doi: 10.1080/02699050050203577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hockey Canada. Hockey Canada Semi-annual meeting report. 2007;(2) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wennberg R A, Tator C H. National Hockey League reported concussions, 1986–87 to 2001–02. Can J Neurol Sci. 2003;30(3):206–209. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100002596. http://cjns.metapress.com/openurl.asp?genre=article&issn=0317-1671&volume=30&issue=3&spage=206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honey C R. Brain injury in ice hockey. Clin J Sport Med. 1998;8(1):43–46. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199801000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodman D, Gaetz M, Meichenbaum D. Concussions in hockey: There is cause for concern. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(12):2004–2009. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200112000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts W O, Brust J D, Leonard B, Hebert B J. Fair-play rules and injury reduction in ice hockey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150(2):140–145. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170270022003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinto M, Kuhn J E, Greenfield M L, Hawkins R J. Prospective analysis of ice hockey injuries at the Junior A level over the course of one season. Clin J Sport Med. 1999;9(2):70–74. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199904000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regnier G, Boileau R, Marcotte G. Effects of body-checking in the Pee Wee (12 and 13-years-old) division in the Province of Quebec. In: Castaldi C R, Hoerner E F, editors. Safety in Ice Hockey. Philadelphia: American Society for Testing Materials; 1989. pp. 84–103. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tator C H, Carson J D, Cushman R. Hockey injuries of the spine in Canada, 1966-1996. CMAJ. 2000 Mar 21;162(6):787–788. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmid/10750464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Canadian Sport Policy. http://www.pch.gc.ca/progs/sc/pol/pcscsp/2003/index_e.cfm.