Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by brain pathology of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and extracellular amyloid plaques. NFTs contain aberrantly hyperphosphorylated Tau as paired helical filaments (PHFs). Although NFs have been shown immunohistologically to be part of NFTs, there has been debate that the identity of NF proteins in NFTs is due to the cross-reactivity of phosphorylated NF antibodies with phospho-Tau. Here, we provide direct evidence on the identity of NFs in NFTs by immunochemical and mass spectrometric analysis. We have purified sarkosyl-insoluble NFTs and performed liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry of NFT tryptic digests. The phosphoproteomics of NFTs clearly identified NF-M phosphopeptides SPVPKS*PVEEAK, corresponding to Ser685, and KAES*PVKEEAVAEVVTITK, corresponding to Ser736, and an NF-H phosphopeptide, EPDDAKAKEPS*KP, corresponding to Ser942. Western blotting of purified tangles with SMI31 showed a 150-kDa band corresponding to phospho-NF-M, while RT97 antibodies detected phospho-NF-H. The proteomics analysis also identified an NF-L peptide (ALYEQEIR, EAEEEKKVEGAGEEQAAAK) and another intermediate filament protein, vimentin (FADLSEAANR). Mass spectrometry revealed Tau phosphopeptides corresponding to Thr231, Ser235, Thr181, Ser184, Ser185, Thr212, Thr217, Ser396, and Ser403. And finally, phosphopeptides corresponding to MAP1B (corresponding to Ser1270, Ser1274, and Ser1779) and MAP2 (corresponding to Thr350, Ser1702, and Ser1706) were identified. In corresponding matched control preparations of PHF/NFTs, none of these phosphorylated neuronal cytoskeletal proteins were found. These studies independently demonstrate that NF proteins are an integral part of NFTs in AD brains.—Rudrabhatla, P., Jaffe, H., Pant, H. C. Direct evidence of phosphorylated neuronal intermediate filament proteins in neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs): phosphoproteomics of Alzheimer's NFTs.

Keywords: Tau, sarkosyl, AD brain

Alzheimer, in his original description of the pathology of a brain from a patient with dementia, identified neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) as a key diagnostic feature (1). Together with extracellular amyloid plaques, they represent the hallmark pathology of AD and have been the focus of investigation for many decades. A large number of studies showed that NFTs correlated well with the clinical expression of dementia in AD (2–6). NFTs target selective populations of neurons, and particularly, specific layers of the cortex. Accordingly, the origin, nature, and structure of NFTs have been the focus of biochemical, immunological, and electron microscopic investigations over the years. An early EM study identified paired helical filaments (PHFs) as a principal constituent of NFTs (7). A tangle/PHF-enriched fraction was later isolated, adequate for the production of a PHF antibody (8, 9), which reacted with NFTs in situ. Because of their insolubility, procedures for the isolation of purified PHF fractions called for detergents so as to facilitate biochemical analyses of the core proteins (10, 11). Meanwhile, antibodies to neuronal cytoskeletal proteins, microtubules (MTs), NFs, and MAPs were tested in AD brain sections and purified PHF fractions. It was shown that NFTs/PHFs reacted with antibodies to NFs (12–18) and, most important, the MT-associated protein, tau (19–22). The phosphorylated tau was identified as the principal core protein in PHFs that is responsible for their solubility properties (13, 23). Although it was early recognized that antibody cross-reactivity between cytoskeletal proteins was a possibility (17), only later was it confirmed (24, 25). It was the latter study that reported that most NF antibodies cross-react with tau (from rat brain), indicating that they shared epitopes at phosphorylated sites (25). On the other hand, it was shown by immunohistochemistry that NFs are a regular component of AD tangles (17, 26, 27). A vast literature has accumulated over the years proposing the roles of tau hyperphosphorylation and β-amyloidosis in the progression of AD. The question of NFs as a significant constituent of PHFs was left open, however, to an independent confirmation of their presence. Nevertheless, NFs are the most abundant proteins of the mature nervous system and determine axonal caliber and conduction velocity of the nerve fiber. While their phosphorylation provides stability to large axons, they also serve in calcium buffering, among many other neuronal functions (28). Several studies have recently demonstrated a drastic loss of nonphosphorylated immunoreactive NF protein (NF antibody, SMI32) in pyramidal cells in the frontal, inferior temporal, and visual cortices in AD (29–34). It was suggested that these changes in neuronal cytoskeleton lead to NFT pathology in AD since the loss of pyramidal neurons containing SMI32 is associated with brain atrophic changes in AD and has been correlated with memory and cognitive impairment in the disease progression (35, 36). Previous reports including our group have revealed the immunohistochemistry of AD tangles with RT97 antibodies, suggesting the presence of NFs in AD (37). This suggests that abnormally phosphorylated NF proteins may be constituents of PHF in AD brains, consistent with the earlier immunological observations. To this end, we decided to isolate and purify PHFs according to the standard protocols and analyze them by the mass spectrometry procedure.

In the present study, we provide direct and independent evidence that aberrantly phosphorylated NF-M/H are integral components of AD tangles. In addition to p-Tau peptides, we have detected phosphopeptides corresponding to NF-M, NF-H, MAP1B, and MAP2. Proteomic analysis of NFTs also resulted in the identification of vimentin and low-molecular-weight NF (NF-L). These data provide an independent confirmation of the presence of NF proteins as integral constituent of NFTs from AD brain and signal the need to address the significance of NFs in the pathology and etiology of AD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Phosphorylated NF monoclonal antibody SMI31 was purchased from Covance (Gaithesburg, MD, USA). RT97 monoclonal antibody clone was a kind gift from Dr. Brian Anderton (Institute of Psychiatry, London, UK) and Dr. Ralph Nixon (Nathan Kline Institute, Orangeburg, NY, USA). The pTau-Ser262 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and p-Thr231 was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Sarkosyl, trypsin, and β-tubulin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Frozen samples of age- and postmortem-matched control and AD brains were obtained from the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (Belmont, MA, USA).

Methods

Preparation of NFTs from AD brain

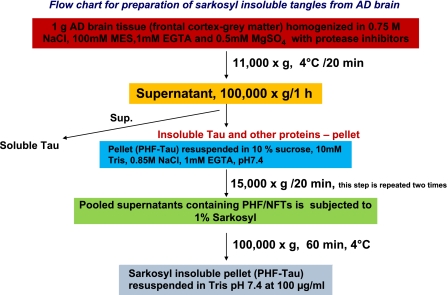

Samples of frozen (−80°C) control and AD brains (63 yr, control 1 and AD 1; 81 yr, control 2 and AD 2) corresponded to 1 g of gray matter of frontal cortex. Meninges and blood vessels were cleaned from the brain tissue. We have followed the sarkosyl solubility method for the isolation and purification of NFTs (38, 39). In brief, the tissue (1 g) was homogenized in 1 ml of buffer [pH 6.5; 0.75 M NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM MgSO4, and 100 mM 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid] along with protease inhibitor and centrifuged at 11,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The pellet was discarded, and supernatant was centrifuged in an ultracentrifuge at 100,000 g for 60 min at 4°C. The supernatant was saved, and the pellet was subjected to sarkosyl solubilization by resuspension in PHF/NFT extraction buffer containing sucrose (10 mM Tris; 10% sucrose; 0.85 M NaCl; and 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4) and spun at 15,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. Under these conditions, isolated PHFs and/ or small PHF aggregates remain in the supernatant, whereas intact or fragmented NFTs and larger PHF aggregates are pelleted. The pellet was reextracted in the sucrose buffer at the same low-speed centrifugation. The supernatants from both sucrose extractions were pooled and subjected to 1% sarkosyl solubilization by stirring at ambient temperature, then centrifuged at 100,000 g for 60 min at 4°C in a Beckman 60 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Sarkosyl treatment removes membranous material from the crude PHF preparations, thereby enriching for PHFs/NFTs. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCL (pH 7.4), using 0.5 μl of buffer for each milligram of initial weight of brain sample protein, and designated the NFT preparation.

Protein estimation

Protein concentration in the samples from control and AD brains was estimated in triplicate using BCA protein assay (40).

Western blotting

Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (41). Western blotting was performed using phospho-Tau and phospho-NF-M/H antibodies. Both SMI31 and RT 97 were used at 1:3000 concentrations. The pTau Ser262 was used at 1:1000 (0.2 μg/μl), and pTau Thr231 was used at 1:2000. The equal loading of the protein samples was confirmed by immunoblotting with β-tubulin (1:2500).

Protein digestion and mass spectrometry-phosphoproteomics

Protein (100 μg) from the NFT preparation was dried in the SpeedVac (ThermoSavant, Farmingham, NY, USA) and dissolved in 8 M urea/0.4 M NH4HCO3 for reduction by dithiothreitol and alkylation by indoacetic acid. After dilution to 2 M urea/0.1 M NH4HCO3, tryptic digestion was performed according to a standard protocol (42) as described previously (43). Digested samples were then acidified with trifluoroacetic acid, combined, and cleaned up utilizing Oasis HLB medium (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA). Eluted digests were dried in the SpeedVac system and subjected to phosphopeptide enrichment by TiO2 chromatography, according to the method of Wu et al. (43). Phosphopeptide-enriched samples were finally analyzed with liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectroscopy (MS/MS) on an LTQ XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corp., San Jose, CA, USA) with the instrument set up to acquire a full survey scan followed by a collision-induced dissociation MS/MS spectrum on each of the top 10 most abundant ions in the survey scan. MS/MS spectra were searched by using the SEQUEST program (Thermo Electron) against a human FASTA database to identify phosphopeptides and specific phosphorylation sites.

Proteomics

TiO2 flow-through was retained and subjected to proteomic analysis to detect the nonphosphorylated proteins in NFT preparations. The MS/MS peptide sequences were searched by SEQUEST against the FASTA database as described above.

RESULTS

Western blot analysis of control and AD brains

The flowchart for the preparation of NFTs is shown in Fig. 1. After the first step of low-speed centrifugation at 11,000 g, the pellet was discarded, and supernatant was subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C in order to obtain soluble and insoluble tau. Western blotting was performed on both fractions from control and AD brain samples. Figure 2A shows the Coomassie blue stain of 100,000 g sarkosyl soluble fractions from 2 control and 2 AD brains (lanes 1–4) and corresponding insoluble fractions (lanes 5–8), ages 63 yr (control 1 and AD1) and 81 yr (control 2 and AD2). Immunoblot analysis was performed with phospho-Tau S262 (p-Ser262 antibody; Fig. 2B). The p-Ser262 antibody cross-reacted with high-molecular-weight NF phosphoproteins (NF-M/H) and high-molecular-weight MAPs (HMW MAPs), as shown in Fig. 2B (lanes 7 and 8). Phosphorylated Tau and the HMW phosphoproteins were not detected in the soluble lysates (either control or AD) but were strongly expressed in the AD insoluble fraction. Evidently, the HMW proteins in the AD fraction share the epitope surrounding Ser262 in tau. The insoluble fractions subjected to SMI31 immunoblotting exhibited higher phospho-NF-M/H in AD brains compared to control brains (Fig. 2D). The 100,000 g pellets were processed to isolate the NFTs as described in Materials and Methods.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the preparation of NFTs from AD brain by sarkosyl insoluble tau tangles preparation.

Figure 2.

Postmortem control (C1, 63 yr; C2, 81 yr) and AD brains (AD1, 63 yr; AD2, 81 yr) were homogenized and subjected to low-speed centrifugation at 11,000 g for 15 min. Supernatant of the low-speed centrifugation was subjected to ultracentrifugation to obtain soluble and insoluble lysates. A) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of 100,000 g soluble fraction (supernatant; lanes 1–4) and insoluble fraction (pellet; lanes 4–8). B) Western blot of SDS-PAGE gel in A, produced using phospho tau (S-262) antibody. Lanes correspond to soluble (lanes 1–4) and insoluble fractions (lanes 5–8) from control and AD brain lysates. Lane 1 and 5, C1; lanes 2 and 6, C2; lanes 3 and 7, AD1; lanes 4 and 8, AD2. C) β-Tubulin was used to show the equal protein load. D) Western blot of 100,000 g pellet of samples, using SMI 31 antibody.

NFT preparation and identification of phospho-Tau isoforms

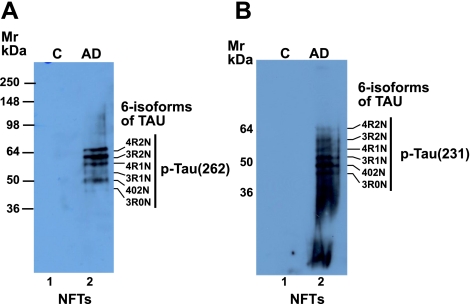

Purified NFTs were analyzed by immunoblotting with phospho-Tau antibodies pThr231 and p-Ser262. Figure 3 shows the expression of pSer262 and p-Thr231 in NFT fractions from control (lane 1) and AD brains (lane 2), respectively. Both antibodies detected all 6 isoforms of tau (4R2N, 3R2N, 4R1N, 3R1N, 402N, and 3R0N) in the NFT preparation from AD brain, while the control NFT fractions were negative. Of the 6 isoforms detected by pSer262, 4R2N, 3R2N, 4R1N, and 402N were intense compared to 3R1N and 3R0N (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, expression of the 4R2N isoform with pThr231 was less intense compared to the others (Fig. 3B). These results demonstrate that only the AD NFT fractions contain phosphorylated tau.

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of PHF/NFTs with phospho-Tau Thr231 (A) and p-Tau Ser262 Tau (B). p-Tau-262 and pTau-231 immunoblot analysis of NFT showed all 6 isoforms of Tau as labeled, 4R2N, 3R2N, 4R1N, 3R1N, 402N, 3R0N. Full-length 3-repeat tau (3R2N) and 4-repeat tau (4R2N) containing N-terminal inserts are encoded by exons 2 and 3; MT-binding repeats are encoded by exons 9–12. The 6 different tau isoforms are generated by alternative splicing of exons 2, 3, and 10. Tau isoforms 3R0N and 4R0N do not include exons 2 and 3. Exclusion of alternatively spliced exon 10 generates 3-repeat tau isoforms. Inclusion or exclusion of alternatively spliced exons 2 and 3 generates 3R1N, 4R1N, 3R2N, or 4R2N tau isoforms.

Detection of phosphorylated NF-M/H in NFTs

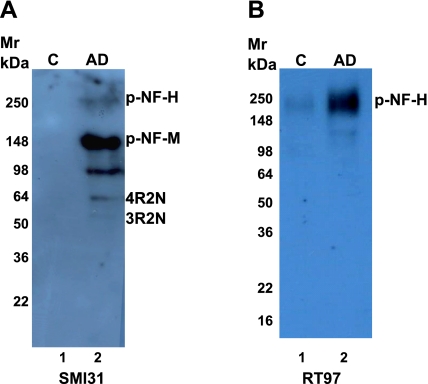

To determine whether the NFT preparations contained neuronal intermediate filaments, they were subjected to immunoblotting with two well-documented antibodies that recognize phosphorylated epitopes of NF-M and NF-H, SMI31 and RT97. With SMI31, a strong immunoreactivity was detected at 150 kDa, corresponding to NF-M, a band corresponding to NF-H and also Tau isoform 1 at 64 kDa (Fig. 4A). We have shown earlier that SMI31 antibodies cross-react with Tau at higher concentrations (37). Immunoblots with RT97, which is selective for NF-H and does not detect phospho-Tau, showed significant immunoreactivity corresponding to NF-H in the AD fraction but not in the control, suggesting that NFTs contain NF-H (Fig. 4B). Note that no tau expression is seen with RT97 antibody. Summarizing, these immunoblots of a purified NFT fraction from AD brains indicate the presence of both NF-M and NF-H in addition to tau.

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of NFTs with SMI31 (A) and RT97 antibodies (B).

Mass spectrometry analysis confirms the presence of neuronal intermediate filaments NF-M and NF-H in a purified NFT preparation from AD brain

Phosphoproteomics of NFTs

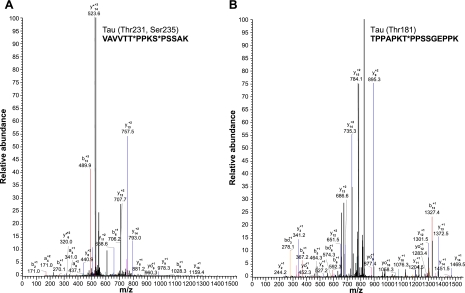

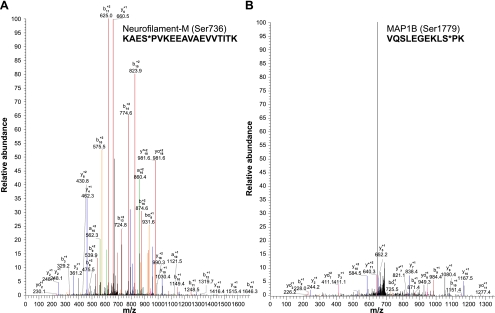

We performed mass spectrometry analysis of phosphopeptides from tryptic digests of purified NFTs from AD brain. We detected a Tau phosphopeptide, VAVVRT*PPKS*PSSAK, which is phosphorylated at two sites, Thr231 and Ser235 (Fig. 5A). In addition, tau phosphopeptides TPPAPKTT*PPSSGEPPK (Thr181; Fig. 5B), TPPAPKTTPPS*SGEPPK (Ser184), TPPAPKTTPPSS*GEPPK (Ser185), and TPSLPT*PPTR (Thr217), listed in Table 1, were also identified. We have also detected Tau phosphopeptides corresponding to Thr212, Thr217, Ser396, Ser400, and Thr403 (Table 1). Significantly, several NF phosphopeptides were also identified. We have detected the phospho-NF-M peptides SPVPKS*PVEEAK, corresponding to Ser685, and KAES*PVKEEAVAEVVTITK, corresponding to Ser736 (Fig. 6A and Table 2). We have also detected an additional NF-M peptide, VSGSPSS*GFRSQSWSR, corresponding to Ser33, and an NF-H peptide, EPDDAKAKEPS*K, corresponding to Ser942 (Table 2). These results confirm that NFTs are composed of NF-M and NF-H in addition to tau. The phosphoproteomics analysis also showed the identity of MAP1B phosphopeptides corresponding to Ser1779 (Fig. 6B) and Ser1270 and Ser1274 and MAP2 phosphopeptides pertaining to Thr350, Ser1702, and Ser1706 (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Analysis of MS/MS spectra after TiO2 enrichment of tryptic digest peptides identified tau phosphopeptides corresponding to Thr-231 and Ser235, VAVVTT*PPKS*PSSAK (A); and Thr181, TPPAPKT*PPSSGEPPK (B). Mass spectrum represents fragment ions corresponding to the phosphopeptide.

Table 1.

Phosphopeptides and phosphorylation sites identified in NFT Tau

| Phosphopeptide | MH+ | Phosphorylation site |

|---|---|---|

| TPPAPKT*PPSSGEPPK | 1667.8 | Thr181 |

| TPPAPKTPPS*SGEPPK | 1667.8 | Ser184 |

| TPPAPKTPPSS*GEPPK | 1667.8 | Ser185 |

| VAVVRT*PPKS*PSSAK | 1131.63 | Thr231, Ser235 |

| SRT*PSLPT*PPTR | 1469.65 | Thr212, Thr217 |

| TPSLPT*PPTR | 1146.55 | Thr217 |

| TDHGAEIVYKS*PVVSGDTSPR | 2295.06 | Ser396 |

| TDHGAEIVYKSPVVS*GDTSPR | 2295.06 | Ser400 |

| TDHGAEIVYKS*PVVSGDT*SPR | 2375.03 | Ser396, Thr403 |

Figure 6.

A) Analysis of MS/MS spectra after TiO2 enrichment of tryptic digested peptides identified the NF-M phosphopeptide, KAES*PVKEEAVAEVVTITK, corresponding to Ser736. Mass spectra exhibit fragment ions corresponding to phosphopeptide. B) Also identified was a MAP1B phophopeptide, VQSLEGEKLS*PK, corresponding to Ser1779.

Table 2.

Phosphopeptides and phosphorylation sites identified in NF-M and NF-H

| NF | Phosphopeptide | MH+ | Phosphorylation site |

|---|---|---|---|

| NF-M | SPVPKS*PVEEAK | 1347.655 | Ser685 |

| NF-M | KAES*PVKEEAVAEVVTITK | 2108 | Ser736 |

| NF-M | VSGSPSS*GFRSQSWSR | 1719.78 | Ser33 |

| NF-H | EPDDAKAKEPS*K | 1431 | Ser942 |

Table 3.

Phosphopeptides and phosphorylation sites identified in MAP1 and MAP2

| MAP | MH+ | Sequence | Phosphorylation site |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAP1B | 1394.69 | VQSLEGEKLS*PK | Ser1779 |

| MAP1B | 2858.38 | VLSPLRS*PPLIGSESAYESFLSADDK | Ser1274 |

| MAP1B | 2858.38 | VLS*PLRSPPLIGSESAYESFLSADDK | Ser1270 |

| MAP2 | 1651 | KIDLS*HVTS*KCGS*LK | Ser1702, Ser1706 |

| MAP2 | 1575 | VAIIRT*PPKSPATPK | Thr350 |

MH+ represents the mass of the singly charged phosphopeptide ion.

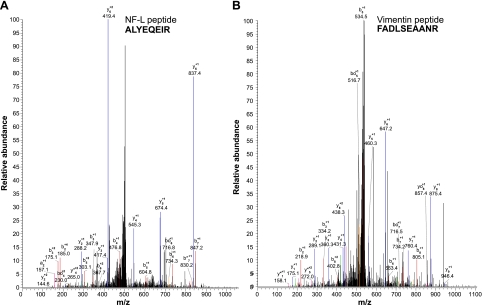

Proteomics of tangles

In addition to the TiO2 phosphoproteomic analysis, we have further performed a nonphosphorylated peptide analysis by an MS/MS of the flow-through from the TiO2 column. This provided an identification of cytoskekeletal protein peptides in the purified NFT preparation, as summarized in Table 4. Seven nonphosphorylated peptides from 3 tau isoforms were identified, along with 1 NF-M peptide and 2 from NF-L. Moreover, 7 peptides from 4 different MAP isoforms were also recognized, along with one from another intermediate filament protein, vimentin. The mass spectrum of NF-L and vimentin are shown in Fig. 7A, B, respectively. Although the spectrometric analysis confirms the immunological data as to the presence of NFs, it is also telling us that the NFT preparation is far more complex than that of tau paired helical filaments and that the contribution of each of these cytoskeletal proteins to the neuronal pathology should be explored.

Table 4.

Peptides identified in NFTs

| Peptide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Tau isoform 1 | TKIATPRGAAPPGQK |

| TPSLPTPPTR | |

| IGSLDNITHVPGGGNK | |

| LQTAPVPMPDLK | |

| QEFEVMEDHAGTYGLGDRK | |

| Tau isoform 3 | AEEAGIGDTPSLEDEAAGHVTQAR |

| Tau isoform 4 | VQIVYKPVDLSK |

| NF-M | SEEVATKEELVADAK |

| NF-L | ALYEQEIR |

| EAEEEEKKVEGAGEEQAAK | |

| Vimentin | KFADLSEAANR |

| MAP1B isoform 2 | VQSLEGEKLSPK |

| SRLASVSADAEVAR | |

| MAP2 isoform 1 | MEFHDQQELTPSTAEPSDQKEK |

| SRLASVSADAEVAR | |

| MAP6 isoform 2 | EEVASAVSSSYR |

| MAP4 isoform 1 | KCSLPAEEDSVLEK |

Proteomics of NFTs revealed the identity of NF, Tau, MAP1B, and vimentin peptides.

Figure 7.

Proteomic analysis resulted in the identification of NF-L peptide, ALYEQEIR (A); and vimentin peptide, FADLSEAANR (B).

DISCUSSION

NFTs are a predominant feature in the pyramidal cells of hippocampus and in the cerebral cortex of people with AD. Tau deposits occur in dystrophic neuritis, as fine neuropil threads, and as massive neurofibrillary tangles in neuronal cell bodies. Do NFTs contain proteins other than tau? We have convincingly demonstrated by an independent method, i.e., mass spectrometry and immunohistochemistry, that NFs, NF-L, NF-M, and NF-H, are indeed integral components of NFTs in AD brains. In addition to these NF phosphopeptides (NF-M, NF-H), 3 nonphosphopeptides have also been recorded, including 2 from NF-L. The presence of all 3 NF subunits suggests that intact 10-nm NFs may also be integrated into PHFs/NFTs. The mass spectroscopic and immunochemical data presented in this study confirm a series of immunological studies in the 1980s eighties that demonstrated NFs in NFTs in situ and in preparations of PHF purified from AD brain tissue (12, 14–17). Western blots of purified PHF preparations with NF phospho-specific antibodies, SMI31 and RT97 also showed robust expression of NF-H at 250 kDa and NF-M at 150 kDa. Note that the antibody concentrations used here were 1:3000 which, in the case of SMI31, revealed a particularly stronger band at 150 kDa corresponding to p-NF-M. In previous studies, the MT preparation was used to isolate phospho-tau from rat brain (25). Their target preparation from rat brain was MAPs, the heat-stable supernatant MT-associated protein fraction (i.e., tau) using the assembly/disassembly, (twice-cycled MTs), method of Shelanski et al. (44). Since non-phospho-tau binds MTs and stabilizes the MT structure, and the phosphorylated tau dissociates from MTs and destabilizes MTs, the tau used in these studies apparently should be minimally phosphorylated, if at all. In addition, NF antibody concentrations used for Western blotting were at least an order of magnitude higher than those used in current study, varying from 1:10 to 1:300, depending on antibody; SMI31 and RT97 were used at a 1:300 dilution. Hence, it is not surprising that these very high concentrations stained different isoforms of tau in the heat-stable preparation. Specificity, however, becomes more evident, particularly at a 10-fold dilution. RT97, for example, at 1:300 displayed 6 tau isoforms in the normal rat preparation (where tau phosphorylation levels, as in normal human brain should be low). In the present as well as in a previous study (37), tau was not detected with RT97, although pNF-H was expressed robustly (Fig. 4).

The NF-M phosphopeptides identified in NFTs, KAES*PVKEEAVAEVVTITK, corresponding to Ser685, and SPVPKS*PVEEAK, corresponding to Ser736, are within the carboxy-terminal domain KSP domain of NF-M. We have reported by quantitative phosphoproteomics that Ser685 is 5.97-fold higher and Ser736 is 7.11-fold abundantly phosphorylated in AD brain compared to normal brain (37). Aberrant phosphorylation of NFs is detected not only in the NFTs, but also in both triton-X insoluble and soluble fractions of brain lysate (45). The peptide VSGSPSS*GFRSQSWSR, corresponding to Ser33, in the N-terminal region of NF-M has been identified. The role of N-terminal domain phosphorylation of NF-M has not been shown to be involved in any neuropathology, although it has been identified in abnormally hyperphosphorylated NFs extracted from neurons treated with okadaic acid (46).

As expected, the mass spectrometric/phosphoproteomic analysis revealed an abundance of tau peptides, phosphopeptides, and nonphosphorylated peptides representing tau isoforms (Tables 1 and 4). Six isoforms of tau exist in human brain (47), differing by the presence or absence of two types of amino acid insertion in the amino-terminal half of the molecule (inserts 1 and 2) and one of the amino acid insertion in the carboxy-terminal half of tau (48). Our spectrometric and Western blot data confirm that all 6 full-length tau isoforms are present in PHF/NFTs isolated from the AD brain. Moreover, our data are in full agreement with previous studies (including mass spectrometric) identifying tau phosphorylation sites in PHF, including pThr231 which is strongly associated with the appearance of NFTs (23, 49–54). Most sites identified occupy motifs for proline-directed kinases (e.g., Erk1/2, SAPK, Cdk5, GSK3) in addition to casein kinase 1. Our data confirm previous studies showing that the most densely phosphorylated sites correspond to the central region of Tau (175–238), flanking the MT-binding region.

What is most striking in our proteomic analysis of PHF is the abundance of MAP peptides phosphorylated from MAP1 (Ser1779, Ser1270, and Ser1274) and MAP2 (Thr350, Ser1702, and Ser1706) as well as 6 nonphosphorylated peptides from isoforms of MAP1B, MAP2, MAP4, and MAP6. Together with the one vimentin peptide, the data suggest that the purified NFTs are a complex of filamentous cytoskeletal proteins, tau, MAPs, and the intermediate filament proteins, vimentin and NFs. If so, then antibody cross-reactivity should be expected, particularly between tau and NFs, since they share common phosphorylated epitopes. If these proteins are integral components of PHFs, we need to explore their contribution to the origin and evolution of NFTs.

Can NFs be used as biomarkers for the early detection of AD? Since neuronal intermediate filaments are the major components of neuronal cytoskeleton, aberrant regulation of some of these structures may contribute to the tangle pathology seen in neurodegenerative disorders. Moreover, neuronal death and degeneration may release fragments of these proteins into body fluids at sufficient levels to be easily detected by specific antibodies at early, preclinical stages of AD. A battery of antibodies to NF-specific phosphoepitopes and Tau in NFTs may offer a unique approach to the design of effective early biomarkers.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the grants from the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health. The authors acknowledge the Harvard Brain Resource Center (Boston, MA, USA) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Brain and Tissue Bank (Bethesda, MD, USA) for providing human brain tissue. The authors thank Dr. Philip Grant for extensive editing and reviewing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alzheimer A. (1907) Über eine eigenartige. Erkrankung der Hirnrinde. J. Gen. Psychiatr. (German) 64, 146–148 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arriagada P. V., Growdon J. H., Hedley-Whyte E. T., Hyman B. T. (1992) Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 42, 631–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bierer L. M., Hof P. R., Purohit D. P., Carlin L., Schmeidler J., Davis K. L., Perl D. P. (1995) Neocortical neurofibrillary tangles correlate with dementia severity in Alzheimer's disease. Arch. Neurol. 52, 81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gomez-Isla T., Price J. L., McKeel D. W., Jr., Morris J. C., Growdon J. H., Hyman B.T. (1996) Profound loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons occurs in very mild Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 16, 4491–4500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guillozet A. L., Weintraub S., Mash D. C., Mesulam M. M. (2003) Neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid, and memory in aging and mild cognitive impairment. Arch. Neurol. 60, 729–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mitchell T. W., Mufson E. J., Schneider J. A., Cochran E. J., Nissanov J., Han L. Y., Bienias J. L., Lee V. M., Trojanowski J. Q., Bennett D. A., Arnold S. E. (2002) Parahippocampal tau pathology in healthy aging, mild cognitive impairment, and early Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 51, 182–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kidd M. (1963) Paired helical filaments in electron microscopy of Alzheimer's disease. Nature 97, 192–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iqbal K., Wiśniewski H. M., Shelanski M. L., Brostoff S., Liwnicz B. H., Terry R. D. (1974) Protein changes in senile dementia. Brain Res. 77, 337–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grundke-Iqbal I., Johnson A. B., Terry R.D, Wisniewski H.M., Iqbal K. (1979) Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles: antiserum and immunohistological staining. Ann. Neurol. 6, 532–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Selkoe J., Ihara Y., Salazar F. J. (1982) Alzheimer's disease: Insolubility of partially purified paired helical filaments in sodium dodecyl sulphate and urea, Science 215, 1243–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iqbal K., Zaidi T., Thompson C. H., Merz P. A., Wisniewski H. M. (1984) Alzheimer paired helical filaments: bulk isolation, solubility, and protein composition, Acta Neuropathol. 62, 167–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ishii T., Haga S., Tokutake S. (1979) Presence of neurofilament protein in Alzheimer's neurofibrillary tangles (ANT). An immunofluorescent study. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 48, 105–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ihara Y., Nukina N., Sugita H., Toyokura Y. (1981) Staining of Alzheimer's neurofibrillary tangles with antiserum against 200 K component of neurofilament. Proc. Jpn. Acad. 57, 152–156 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anderton B. H., Breinburg D., Downes M. J., Green P. J., Tomlinson B. E., Ulrich J., Wood J. N., Kahn J. (1982) Monoclonal antibodies show that neurofibrillary tangles and neurofilaments share antigenic determinants. Nature 298, 84–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gambetti P., Autilio-Gambetti L., Perry G., Shecket G., Crane R. C. (1983) Antibodies to neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease raised from human and animal neurofilament fractions. Lab. Invest. 49, 430–435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sternberger N. H., Sternberger L. A., Ulrich J. (1985) Aberrant neurofilament phosphorylation in Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82, 4274–4276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miller C. C., Brion J. P., Calvert R., Chin T. K., Eagles P. A., Downes M. J., Flament-Durand J., Haugh M., Kahn J., Probst A., Ulrich J., Anderton B. H. (1986) Alzheimer's paired helical filaments share epitopes with neurofilament side arms. EMBO J. 2, 269–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kosik K. S., Selkoe D. J., Sapirstein V. (1984) Possible modifications of vimentin following acquisition of triton insolubility. Biochem. Int. 4, 483–490 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Tung Y. C., Wisniewski H. M. (1984) Alzheimer paired helical filaments: immunochemical identification of polypeptides. Acta Neuropathol. 62, 259–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kosik K. S., Joachim C. L., Selkoe D. J. (1986) Microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) is a major antigenic component of paired helical filaments in Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 11, 4044–4048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nukina N., Ihara Y. (1986) One of the antigenic determinants of paired helical filaments is related to tau protein. J. Biochem. 5, 1541–1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Delacourte A., Defossez A. (1986) Alzheimer's disease: tau proteins, the promoting factors of microtubule assembly, are major components of paired helical filaments. J. Neurol. Sci. 76, 173–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Tung Y. C., Quinlan M., Wisniewski H. M., Binder L. I. (1986) Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83, 4913–4917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ksiezak-Reding H., Dickson D. W., Davies P., Yen S. H. (1987) Recognition of tau epitopes by anti-neurofilament antibodies that bind to Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84, 3410–3414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nukina N., Kosik K. S., Selkoe D. J. (1987) Recognition of Alzheimer paired helical filaments by monoclonal neurofilament antibodies is due to cross reaction with tau protein, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84, 3415–3419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perry G., Rizzuto N., Autilio-Gambetti L., Gambetti P. (1985) Paired helical filaments from Alzheimer disease patients contain cytoskeletal components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82, 3916–3920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sternberger L. A., Sternberger N. H. (1983) Monoclonal antibodies distinguish phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms of neurofilaments in situ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 80, 6126–6130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rudrabhatla P., Pant H. C. (2011) Topographic regulation of neuronal intermediate filament proteins by phosphorylation: in health and disease. In Cytoskeleton of the Nervous System, Advances in Neurology, Vol. 3 (Nixon R. A., Yuan A. eds) pp. 627–656, Springer Science, New York [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hof P. R., Cox K., Morrison J. H. (1990) Quantitative analysis of a vulnerable subset of pyramidal neurons in Alzheimer's disease: superior frontal and inferior temporal cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 301, 44–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hof P. R., Morrison J. H. (1990) Quantitative analysis of a vulnerable subset of pyramidal neurons in Alzheimer's disease: II. Primary and secondary visual cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 301, 55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bussiere T., Giannakopoulos P., Bouras C., Perl D. P., Morrison J. H., Hof P. R. (2003) Progressive degeneration of nonphosphorylated neurofilament protein-enriched pyramidal neurons predicts cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease: stereologic analysis of prefrontal cortex area 9. J. Comp. Neurol. 463, 281–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bussiere T., Gold G., Kovari E., Giannakopoulos P., Bouras C., Perl D. P., Morrison J. H., Hof P. R. (2003) Stereologic analysis of neurofibrillary tangle formation in prefrontal cortex area 9 in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience 117, 577–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Giannakopoulos P., Herrmann F. R., Bussiere T., Bouras C., Kovari E., Perl D. P., Morrison J. H., Gold G., Hof P. R. (2003) Tangle and neuron numbers, but not amyloid load, predict cognitive status in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 60, 1495–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ayala-Grosso C., Tam J., Roy S., Xanthoudakis S., Da Costa D., Nicholson D. W., Robertson G. S. (2006) Caspase-3 cleaved spectrin colocalizes with neurofilament-immunoreactive neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience 141, 863–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Morrison J. H., Lewis D. A., Campbell M. J., Huntley G. W., Benson D. L., Bouras C. (1987) A monoclonal antibody to non-phosphorylated neurofilament protein marks the vulnerable cortical neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 416, 331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morrison J. H., Hof P. R. (2002) Selective vulnerability of corticocortical and hippocampal circuits in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Progr. Brain Res. 136, 467–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rudrabhatla P., Grant P., Jaffe H., Strong M. J., Pant H. C. (2010) Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of neuronal intermediate filament proteins (NF-M/H) in Alzheimer's disease by iTRAQ. FASEB J. 11, 4396–4407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee V. M. Y., Wang J. L., Trojanowski J. Q. (1999) Purification of paired helical filament tau and normal tau from human brain tissue. Methods Enzymol. 30, 981–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kelleher I., Garwood C., Hanger D. P., Anderton B. H., Noble W. (2007) Kinase activities increase during the development of tauopathy in htau mice. J. Neurochem. 103, 2256–2267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith P. K., Krohn R. I., Hermanson G. T., Mallia A. K., Gartner F. H., Provenzano M. D., Fujimoto E. K., Goeke N. M., Olson B. J., Klenk D. C. (1985) Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150, 76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stone K. L., Williams K. R. (1993) Enzymatic digestion of proteins and HPLC peptide isolation. In A Practical Guide to Protein and Peptide Purification for Microsequencing (Matsudaira P. ed) pp. 43–69, Academic Press, San Diego, CA, USA [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dosemeci A., Jaffe H. (2010) Regulation of phosphorylation at the postsynaptic density during different activity states of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Com. 391, 78–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wu Q., Shakey W., Liu A., Schuller Follettie M. T. (2007) Global profiling of phosphopeptides by titania affinity enrichment. J. Proteome Res. 6, 4684–4689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shelanski M. L., Gaskin F., Cantor C. R. (1973) Microtubule assembly in the absence of added nucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 70, 765–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shea T. B., Dahl D. C., Nixon R. A., Fischer I. (1997) Triton-soluble phosphovariants of the heavy neurofilament subunit in developing and mature mouse central nervous system. J. Neurosci. Res. 48, 515–523 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sacher M. G., Athlan E. S., Mushynski W. E. (1992) Okadaic acid induces the rapid and reversible disruption of the neurofilament network in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 186, 324–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Goedert M., Jakes R. (1990) Expression of separate isoforms of human tau protein: correlation with the tau pattern in brain and effects on tubulin polymerization. EMBO J. 9, 4225–4230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Goedert M., Trojanowski J. Q., Lee V. M. Y. (1997) The neurofibrillary pathology of Alzheimer's disease. In The Molecular and Genetic Basis of Neurological Disease, 2nd Ed. (Rosenberg R. N., Prusiner S. B., DiMauro S., Barchi R. L. eds) pp. 613–627, Butterworth, Boston [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sengupta A., Kabat J., Novak M., Wu Q., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., (1998) Phosphorylation of tau at both Thr231 and Ser262 is required for maximal inhibition of its binding to microtubules. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 357, 299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kimura T., Yamashita S., Fukuda T., Park J. M., Murayama M., Mizoroki T., Yoshiike Y., Sahara N., Takashima A. (2007) Hyperphosphorylated TAU in parahippocampal cortex impairs place learning in aged mice expressing wild-type human TAU. EMBO J. 26, 5143–5152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mazanetz M. P., Fisher P. M. (2007) Untangling tau hyperphosphorylation in drug design for neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 464–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Alonso Adel C., Li B., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K. (2006) Polymerization of hyperphosphorylated TAU into filaments eliminates its inhibitory activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 8864–8869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Johnson G. V. W., Stoothoff W. H. (2004) Tau phosphorylation in neuronal cell function and dysfunction. J. Cell. Science 117, 5721–5729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hanger D. P., Byers H. L., Wray S., Leung K. Y., Saxton M. J., Seereeram A., Reynolds C. H., Ward M. A., Anderton B. H. (2007) Novel phosphorylation sites in tau from Alzheimer brain support a role for casein kinase 1 in disease pathogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 23645–23654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]