Abstract

Background:

We describe the relationship between World Trade Center (WTC) cough syndrome symptoms, pulmonary function, and symptoms consistent with probable posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in WTC-exposed firefighters in the first year post-September 11, 2001 (baseline), and 3 to 4 years later (follow-up).

Methods:

Five thousand three hundred sixty-three firefighters completed pulmonary function tests (PFTs) and questionnaires at both times. Relationships among WTC cough syndrome, probable PTSD, and PFTs were analyzed using simple and multivariable models. We also examined the effects of cofactors, including WTC exposure.

Results:

WTC cough syndrome was found in 1,561 firefighters (29.1%) at baseline and 1,186 (22.1%) at follow-up, including 559 with delayed onset (present only at follow-up). Probable PTSD was found in 458 firefighters (8.5%) at baseline and 548 (10.2%) at follow-up, including 343 with delayed onset. Baseline PTSD symptom counts and probable PTSD were associated with WTC cough syndrome at baseline, at follow-up, and in those with delayed-onset WTC cough syndrome. Similarly, WTC cough syndrome symptom counts and WTC cough syndrome at baseline were associated with probable PTSD at baseline, at follow-up, and in those with delayed-onset probable PTSD. WTC arrival time and work duration were cofactors of both outcomes. A small but consistent association existed between pulmonary function and WTC cough syndrome, but none with PTSD.

Conclusions:

The study showed a moderate association between WTC cough syndrome and probable PTSD. The presence of one contributed to the likelihood of the other, even after adjustment for shared cofactors such as WTC exposure.

The September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center (WTC) created a hazardous environment where New York City Fire Department (FDNY) rescue workers faced numerous health and safety challenges.1 Virtually every firefighter in FDNY’s workforce participated in the 10-month WTC rescue and recovery effort; thousands subsequently reported respiratory and mental health symptoms.

In 2002, the “WTC cough syndrome,” consisting of an initial cough followed by persistent upper and lower respiratory symptoms, often accompanied by gastroesophageal reflux disorder (GERD),2 was first described by our group. Since then, many investigators have also reported associations between WTC exposure and respiratory symptoms,3‐5 abnormal pulmonary function,2,3,6 and accelerated declines in pulmonary function.7 Likewise, we and others have reported elevated rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or symptoms consistent with PTSD in WTC-exposed rescue/recovery workers4,8,9 and residents.10

Recent studies, all but one in non-WTC exposed groups, have examined relationships between asthma11,12 and other obstructive airways diseases and comorbid illnesses, including psychologic conditions.13 Others have shown relationships between PTSD and physical health ailments, including respiratory diseases,14‐16 and reduced health-related quality of life.17,18

The goal of this study was to examine the relationship between WTC cough syndrome symptoms and symptoms consistent with PTSD, including assessment of delayed onset of symptoms. We also report on the influence of cofactors such as the intensity of WTC exposure and pulmonary function.

Materials and Methods

The FDNY-WTC Medical Monitoring Program performs health evaluations of the FDNY workforce approximately every 18 months. These evaluations include pulmonary function tests and self-administered, computer-based, medical and mental health questionnaires. Study participation requires informed written consent; the study was approved (No. 02-02-041 and No. 07-09-320) by our institutional review board at the Montefiore Medical Center.

Study Participants and Time Periods

As of September 10, 2005, the end of the study period, 10,074 firefighters who reported first arrival at the WTC site in the first 2 weeks after September 11, 2001, were enrolled in the FDNY-WTC Medical Monitoring Program. We excluded data from 2,013 firefighters who did not remain part of the active workforce during the study period, from 1,272 without a baseline questionnaire, and from 1,131 without a follow-up questionnaire. Because we were also interested in spirometry results, we additionally excluded 295 firefighters without pulmonary function test results performed on the day that the questionnaire was completed. This left 5,363 firefighters in our analytic cohort.

WTC Exposure Status

Exposure group definitions were based on initial arrival time at the WTC site as follows: (1) arriving on the morning of September 11, 2001, and present during the tower collapses; (2) arriving during the afternoon of September 11, 2001; (3) arriving on September 12, 2001; or (4) arriving between days 3 and 14. The duration variable was based on summing the number of months participants worked at the site, from September 2001 through July 2002. Both variables were based on questionnaire responses.

Tobacco Smoking Status

Using questionnaire responses, smoking status was grouped into current, former, and never smokers. Pack-year data were also recorded.

Pulmonary Function Test

Spirometry was performed according to American Thoracic Society guidelines and quality assurance standards.19 FEV1 was expressed as percent predicted based on Hankinson prediction equations.20

PTSD Symptoms

PTSD symptoms were based on items in the PTSD checklist (PCL),21 but were modified for speed of administration. Details of the FDNY-modified PCL (PCL-m) administered at each health evaluation have been described previously.8 Questions were also modified to fit the context of September 11, 2001. For example, at both time points participants were asked, “Since the disaster, have you experienced any of the following…?” Answer choices were binary (yes/no).

Probable PTSD

Questionnaire responses alone cannot establish a diagnosis of PTSD. Because our outcome measure was based only on the PCL-m, we refer to those who met our threshold as having “probable PTSD,” consistent with previous literature.22 Two conditions were required. The first was based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition, Text Revision) (DSM-IV-TR)23 criteria and required at least two affirmative responses in the arousal domain, at least one in the reexperiencing domain, and at least three in the avoidance/numbing domain. The second condition was a summary score of at least nine affirmative responses, which was determined to be an appropriate threshold for probable PTSD in this population in our previous work.8 Individuals with probable PTSD met the most conservative definition, satisfying both criteria. In a recent analysis, agreement between the PCL-m and the PCL was high (κ = 0.85) in our population.24 The Cronbach α values for the original PCL and the PCL-m were 0.95 and 0.91, respectively. The Cronbach α values for individual domains were 0.87 and 0.81 for arousal, 0.90 and 0.85 for avoidance, and 0.90 and 0.75 for reexperiencing, respectively.

WTC Cough Syndrome Symptoms

WTC cough syndrome is a descriptive term and required at least one symptom in each of the three categories (upper respiratory, lower respiratory, and GERD). Lower respiratory symptoms were assessed with the question, “Since the disaster, have you had any of the following new or worsening respiratory symptoms?” Possible answer choices were “no respiratory symptoms,” “wheezing,” “shortness of breath,” “frequent or daily cough,” or “nighttime cough, wheeze, or shortness of breath interfering with sleep.” Multiple answers were allowed. Upper respiratory symptoms were similarly assessed with answer choices “nasal congestion or drip,” “sore or hoarse throat,” and “difficulty swallowing.” GERD symptoms were assessed using responses of “stomach upset or heartburn” and “chest tightness or pain.” The WTC cough syndrome total symptom score at each time point was a nonweighted summation of the symptoms in each category (maximum score of 9).

Delayed-Onset WTC Cough Syndrome and Probable PTSD

Some firefighters did not meet the criteria for WTC cough syndrome or Probable PTSD at baseline but did at follow-up. They are referred to as “delayed onset” for the respective outcomes.

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate analyses of categoric variables used the χ2 test with OR and 95% CI. Group comparisons of continuous variables were assessed using the Student t test or the Mann-Whitney U test for nonnormally distributed variables. Spearman correlation coefficients are reported. Simple linear regression analysis was used to test the relationships between FEV1 % predicted and symptom counts.

We used multivariable logistic regression analyses to examine associations with WTC cough syndrome and probable PTSD at baseline and follow-up and delayed onset of these outcomes. In delayed-onset models, the symptomatic group was compared with the “resilient” group who did not meet the criteria for WTC cough syndrome or probable PTSD at either baseline or follow-up.25‐27 Firefighters who had a larger symptom count at follow-up than at baseline were considered to have an “increase in symptom count over the study period.” This is stated as a binary variable. Variables tested in all models were selected for plausibility and based on their predictive value in previous studies. They included age on September 11, 2001, WTC exposure (initial arrival time and work duration), FEV1 % predicted, and smoking status. Interaction terms (eg, between WTC arrival time and work duration) were tested but did not remain in final models. Variables remained in final models based on a P value of < .05 and/or assessment of their impact on other variables in the model. We used the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic to assess the goodness-of-fit of final models. Data were analyzed using SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina).

Results

The analytic cohort represented 53.2% of the 10,074 eligible WTC-exposed firefighters (n = 5,363) who completed an examination during the study period. Comparing the analytic cohort with those excluded (n = 4,711), the proportion of persons in the earliest arrival group was similar (15.9% vs 16.0%; χ2 = 0.02, degrees of freedom [df] = 1, P = .89). There were small but statistically significant differences in race (94.6% white vs 92.8% white; χ2 = 14.3, df = 1, P < .01), rank (37.6% officers vs 34.4% officers; χ2 = 11.0, df = 1, P < .01), age on September 11, 2001 (37.8 ± 6.4 years vs 41.7 ± 8.1 years; t = 26.4, df = 8,949, P < .01), and WTC work duration (median 4 months [interquartile range (IQR), 2-6] vs median 3 months [IQR, 2-6]; z = −6.6, P < .01).

Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants by WTC cough syndrome and probable PTSD at either time point (ever). At baseline, WTC cough syndrome was reported by 1,561 of the cohort (29.1%) and probable PTSD by 458 (8.5%); of these, 272 (5.1% of the total sample) had both. At follow-up, WTC cough syndrome was reported by 1,186 participants (22.1%) and probable PTSD by 548 (10.2%); of these, 259 (4.8% of the total sample) reported both. The follow-up sums included 559 firefighters with delayed-onset WTC cough syndrome (47.1% of all WTC cough syndrome at follow-up) and 343 firefighters with delayed-onset probable PTSD (62.6% of all probable PTSD at follow-up). There were significant differences in exposure groups based on arrival time for those with probable PTSD compared with those without (χ2 = 103.1, df = 3, P < .01), and for those with WTC cough syndrome compared with those without (χ2 = 107.9, df = 3, P < .01). Further results can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

—Characteristics by PTSD and WTC Cough Syndrome

| Analytic Cohort (N = 5,363) | Ever WTC Cough (n = 2,120) | Never WTC Cough (n = 3,243) | Statistical Test | dfa | P Value | Ever PTSD (n = 801) | Never PTSD (n = 4,562) | Statistical Test | df | P Value | |

| Arrival time | |||||||||||

| During collapse | 853 (15.9) | 441 (20.8) | 412 (12.7) | χ2 = 107.9 | 3.0 | < .01 | 214 (26.7) | 639 (14.0) | χ2 = 103.1 | 3 | < .01 |

| Afternoon day 1 | 3,647 (68.0) | 1,443 (68.1) | 2,204 (68.0) | … | … | … | 516 (64.4) | 3,131 (68.6) | … | … | … |

| Day 2 | 570 (10.6) | 164 (7.7) | 406 (12.5) | … | … | … | 53 (6.6) | 517 (11.3) | … | … | … |

| Day 3-14 | 293 (5.5) | 72 (3.4) | 221 (6.8) | … | … | … | 18 (2.3) | 275 (6.0) | … | … | … |

| Age group on September 11, 2001 | |||||||||||

| < 25 y | 90 (1.7) | 12 (0.6) | 78 (2.4) | χ2 = 37.6 | 4.0 | < .01 | 6 (0.8) | 84 (1.8) | χ2 = 7.5 | 4 | .11 |

| 25-34 y | 1,822 (34.0) | 678 (32.0) | 1,144 (35.3) | … | … | … | 261 (32.6) | 1,561 (34.2) | … | … | … |

| 35-44 y | 2,686 (50.1) | 1,124 (53.0) | 1,562 (48.2) | … | … | … | 421 (52.6) | 2,265 (49.7) | … | … | … |

| 45-54 y | 740 (13.8) | 299 (14.1) | 441 (13.6) | … | … | … | 111 (13.9) | 629 (13.8) | … | … | … |

| ≥ 55 y | 25 (0.5) | 7 (0.3) | 18 (0.6) | … | … | … | 2 (0.3) | 23 (0.5) | … | … | … |

| Race | |||||||||||

| White | 5,075 (94.6) | 2,019 (95.2) | 3,056 (94.2) | χ2 = 2.5 | 1.0 | .11 | 765 (95.5) | 4,310 (94.5) | χ2 = 1.4 | 1 | .23 |

| Other | 288 (5.4) | 101 (4.8) | 187 (5.8) | … | … | … | 36 (4.5) | 252 (5.5) | … | … | … |

| Rank | |||||||||||

| Firefighters | 3,323 (62.0) | 1,309 (61.8) | 2,014 (62.1) | χ2 = 0.1 | 1.0 | .79 | 477 (59.5) | 2,846 (62.4) | χ2 = 2.3 | 1 | .13 |

| Officers | 2,040 (38.0) | 811 (38.3) | 1,229 (37.9) | … | … | … | 324 (40.5) | 1,716 (37.6) | … | … | … |

| Tobacco useb | |||||||||||

| > 10 pack-y | 174 (3.3) | 75 (3.5) | 99 (3.1) | χ2 = 1.6 | 3.0 | .67 | 37 (4.6) | 137 (3.0) | χ2 = 13 | 3 | < .01 |

| 1-9 pack-y | 393 (7.3) | 150 (7.1) | 243 (7.5) | … | … | … | 67 (8.4) | 326 (7.2) | … | … | … |

| Former smoker | 711 (13.3) | 274 (13.0) | 437 (13.5) | … | … | … | 124 (15.5) | 587 (12.9) | … | … | … |

| Never smoker | 4,077 (76.1) | 1,617 (76.4) | 2,460 (75.9) | … | … | … | 572 (71.5) | 3,505 (76.9) | … | … | … |

| Duration, mo, median (IQR)c | 4 (2-6) | 5 (3-7) | 3 (2-6) | z = 12.9 | … | .01 | 5 (3-8) | 4 (2-6) | z = 10.1 | … | < .01 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. df = degrees of freedom; IQR = interquartile range; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; WTC = World Trade Center.

df for tests = number of groups − 1.

Eight members did not respond to the question about tobacco use.

Significance between these groups for duration distribution tested using Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test.

Individual PTSD and WTC Cough Syndrome Symptoms

Cross-sectional analyses showed each individual WTC cough syndrome symptom was endorsed by a significantly greater proportion of those with probable PTSD than those without, both at baseline and at follow-up (all P < .01). Similarly, each individual PTSD symptom was concurrently endorsed by a significantly greater proportion of those with WTC cough syndrome than those without, both at baseline and at follow-up (all P < .01). Full results can be found in e-Tables 1 and 2.

Total Number of Symptoms and Number by Domain/Category

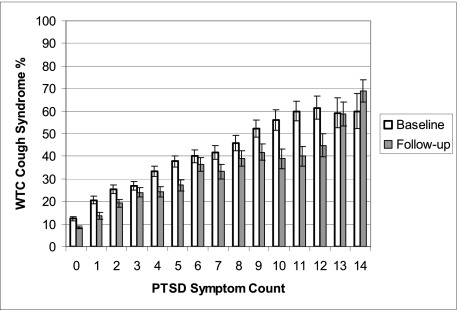

WTC cough syndrome at baseline was associated with PTSD symptom counts at baseline (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.19-1.23) (Fig 1) and symptom counts within each DSM-IV-TR PTSD domain at baseline (arousal OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.36-1.45; avoidance OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.37-1.49; reexperiencing OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.70-1.98). WTC cough syndrome at follow-up was associated with PTSD symptom counts at follow-up (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.19-1.23) (Fig 1) and symptom counts within each DSM-IV-TR PTSD domain at follow-up (arousal OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.41-1.50; avoidance OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.36-1.47; reexperiencing OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.73-2.02).

Figure 1.

PTSD symptom counts and WTC cough syndrome at baseline and follow-up. Rate of WTC cough syndrome in cohort members by number of PTSD symptoms (N = 5,363). Error bars represent SEM. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; WTC = World Trade Center.

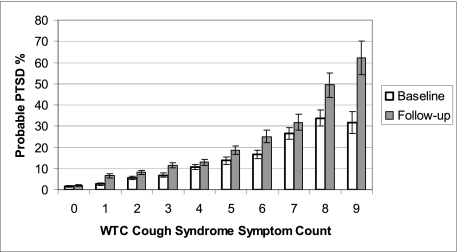

Probable PTSD at baseline was associated with the number of WTC cough syndrome symptoms at baseline (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.41-1.52) (Fig 2) and the number of symptoms within each category (lower respiratory OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.77-2.05; upper respiratory OR, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.97-2.42; and GERD OR, 2.41; 95% CI, 2.13-2.74). Probable PTSD at follow-up was associated with the number of WTC cough syndrome symptoms at follow-up (OR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.43-1.54) (Fig 2) and the number of symptoms within each category (lower respiratory OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.74-2.01; upper respiratory OR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.89-2.30; and GERD OR, 2.45; 95% CI, 2.19-2.75).

Figure 2.

WTC cough syndrome symptom counts and probable PTSD at baseline and follow-up. Rate of probable PTSD in cohort members by number of WTC cough syndrome symptoms (N = 5,363). Error bars represent the SEM. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of abbreviations.

The correlations between WTC cough syndrome symptom counts and PTSD symptom counts were ρ = 0.42 (both reported at baseline) and ρ = 0.46 (both reported at follow-up). The correlation between WTC cough syndrome symptom counts at baseline and PTSD symptom counts at follow-up was ρ = 0.32. The correlation between PTSD symptom counts at baseline and WTC cough syndrome symptom counts at follow-up was ρ = 0.33. All correlations were statistically significant at the P < .01 level.

Spirometry Associations With WTC Cough Syndrome and Probable PTSD

We examined FEV1 % predicted at the baseline examination and at follow-up in relation to the number of WTC cough syndrome and PTSD symptoms. FEV1 % predicted at baseline was associated with the number of WTC cough syndrome symptoms (ρ = −0.08, P < .01), lower respiratory symptoms (ρ = −0.10, P < .01), upper respiratory symptoms (ρ = −0.04, P < .01), and GERD symptoms (ρ = −0.04, P < .01) reported at baseline. FEV1 % predicted at follow-up was also associated with the number of WTC cough syndrome symptoms (ρ = −0.09, P < .01), lower respiratory symptoms (ρ = −0.11, P < .01), and GERD symptoms (ρ = −0.06, P < .01), but was not significantly associated with the number of upper respiratory symptoms (ρ = −0.01, P = .59). FEV1 % predicted was not significantly associated with probable PTSD symptom counts (ρ = −0.02, P = .26), or counts within DSM-IV-TR PTSD symptom groups at baseline (arousal ρ = −0.02, P = .26; avoidance ρ = −0.01, P = .30; reexperiencing ρ < −0.01, P = .56), or follow-up (total ρ = −0.01, P = .30; arousal ρ= −0.02, P = .19; avoidance ρ < −0.01, P = .84; reexperiencing ρ = −0.01, P = .29) in cross-sectional analyses.

Multivariable Regression Models at Baseline, Follow-up, and Delayed Onset

Multivariable logistic regression models for WTC cough syndrome at baseline and at follow-up and for those with delayed onset are shown in Table 2. In all three models, arrival at the WTC site during the collapse, WTC work duration, and age on September 11, 2001, exhibited significant associations. Baseline probable PTSD was also strongly associated with WTC cough syndrome in all models (eg, OR, 3.6; 95% CI, 2.9-4.4 at baseline); follow-up probable PTSD was strongly associated with WTC cough syndrome in the follow-up (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.4-2.2) and delayed-onset (OR 1.8; 95% CI, 1.3-2.5) models. An increase in probable PTSD symptom count over the study period was significantly associated with follow-up WTC cough syndrome (OR 1.9; 95% CI, 1.7-2.3) and delayed onset WTC cough syndrome (OR 2.1; 95% CI, 1.8-2.6). Baseline FEV1 % predicted was inversely associated with WTC cough syndrome at baseline (OR, 0.992; 95% CI, 0.987-0.997). Follow-up FEV1 % predicted was inversely associated with WTC cough syndrome in the follow-up (OR, 0.992; 95% CI, 0.986-0.999) and in the delayed-onset models (OR, 0.990; 95% CI, 0.981-0.998).

Table 2.

—Logistic Models Predicting WTC Cough Syndrome at Year 1 and at Follow-up, and Delayed-Onset WTC Cough Syndrome

| WTC Cough Syndrome Baseline (N = 5,363) |

WTC Cough Syndrome Follow-up (n = 5,363) |

Delayed-Onset WTC Cough Syndromea (n = 3,802) |

||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Arrival during collapse | 2.70 | 1.91, 3.82 | 1.80 | 1.22, 2.67 | 1.69 | 1.20, 2.40 |

| Arrival afternoon day 1 | 1.75 | 1.26, 2.41 | 1.37 | 0.95, 1.97 | 1.49 | 1.13, 1.97 |

| Arrival day 2 | 1.27 | 0.87, 1.84 | 0.96 | 0.62, 1.48 | b | b |

| Duration months | 1.10 | 1.07, 1.12 | 1.10 | 1.07, 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.07, 1.14 |

| Age on September 11, 2001 | 1.01 | 1.01, 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.00, 1.03 |

| Baseline FEV1 % predictedc | 0.992 | 0.987, 0.997 | ||||

| Follow-up FEV1 % predictedc | 0.992 | 0.986, 0.999 | 0.990 | 0.981, 0.998 | ||

| Baseline probable PTSD | 3.59 | 2.93, 4.39 | 1.56 | 1.23, 1.99 | 2.18 | 1.50, 3.16 |

| Follow-up probable PTSD | NA | NA | 1.78 | 1.42, 2.22 | 1.82 | 1.34, 2.47 |

| PTSD score increase | NA | NA | 1.94 | 1.66, 2.26 | 2.14 | 1.75, 2.61 |

| Baseline WTC cough syndrome | NA | NA | 3.24 | 2.81, 3.75 | NA | NA |

FEV1 of exhalation based on the prediction equations of Hankinson.18 OR is adjusted. NA = not applicable. See Table 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Delayed onset is compared with the resilient group, which did not meet symptom thresholds at either time point.

Because of small numbers, delayed-onset models combined arrival day 2 and arrival days 3-14 as a reference for exposure.

Baseline FEV1 was used to test WTC cough syndrome at baseline; follow-up FEV1 was used at follow-up.

Multivariable logistic regression models showing associations with probable PTSD at baseline and follow-up and for those with delayed-onset probable PTSD are shown in Table 3. In all models, arrival during the collapse, WTC work duration, and losing a coworker during the collapse were significant. Association with baseline WTC cough syndrome was present in all models. Follow-up WTC cough syndrome was associated with follow-up probable PTSD (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.5-2.3) and delayed-onset probable PTSD (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.3-2.2). An increase in WTC cough syndrome symptom count during the study period was significantly associated with probable PTSD at follow-up (OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.8-2.8) and delayed-onset probable PTSD (OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.9-3.3). FEV1 % predicted was not significantly associated with probable PTSD in any model.

Table 3.

—Logistic Models Predicting Probable PTSD at Baseline and Follow-up, and Delayed-Onset Probable PTSD

| Probable PTSD Baseline (N = 5,363) |

Probable PTSD Follow-up (n = 5,363) |

Delayed-Onset Probable PTSDa (n = 4,905) |

||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Arrival during collapse | 2.87 | 1.41, 5.81 | 1.94 | 1.07, 3.53 | 1.89 | 1.25, 2.85 |

| Arrival afternoon day 1 | 2.22 | 1.12, 4.39 | 1.28 | 0.73, 2.25 | 1.08 | 0.75, 1.54 |

| Arrival day 2 or later | 1.22 | 0.55, 2.69 | 1.18 | 0.62, 2.28 | b | b |

| Duration months | 1.08 | 1.04, 1.12 | 1.10 | 1.07, 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.08, 1.16 |

| Age on September 11, 2001 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.98, 1.01 |

| Lost firefighter during collapse | 2.67 | 1.79, 3.99 | 1.75 | 1.15, 2.67 | 1.84 | 1.11, 3.05 |

| Baseline FEV1 % predictedc | 1.01 | 0.998, 1.013 | ||||

| Follow-up FEV1 % predictedc | NA | NA | 1.01 | 0.997, 1.014 | 1.00 | 0.992, 1.012 |

| Baseline WTC cough syndrome | 3.59 | 2.93, 4.39 | 1.66 | 1.32, 2.08 | 2.00 | 1.53, 2.62 |

| Follow-up WTC cough syndrome | NA | NA | 1.85 | 1.47, 2.32 | 1.71 | 1.31, 2.24 |

| WTC cough syndrome score increase | NA | NA | 2.22 | 1.76, 2.81 | 2.50 | 1.92, 3.25 |

| Baseline Probable PTSD | NA | NA | 8.51 | 6.73, 10.75 | NA | NA |

FEV1 of exhalation based on the prediction equations of Hankinson.18 See Table 1 and 2 legends for expansion of abbreviations.

Delayed onset is compared with the resilient group, which did not meet symptom thresholds at either time point.

Because of small numbers, delayed-onset models combined arrival day 2 and arrival days 3-14 as a reference for exposure.

Baseline FEV1 was used to test probable PTSD at baseline; follow-up FEV1 was used at follow-up.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of highly exposed WTC firefighters that examined comorbid respiratory and mental health symptoms over time. Using bivariate and multivariable techniques, the concordance between these symptoms at baseline and follow-up was striking, in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. This relationship was consistent whether the analysis was based on individual symptoms, number of symptoms within each WTC cough syndrome category or PTSD domain, or total number of symptoms. The relationship remained statistically significant in multivariable models.

Arrival time during the collapse and work duration at the WTC site were both independent predictors of outcomes in all models, demonstrating a significant exposure response in this population for both respiratory and probable PTSD outcomes. Presence during the collapse entailed unique events that were particularly traumatic. Regarding respiratory health, the potential for lung injury due to inhalation exposure was extreme during the morning of September 11, 2001. Regarding mental health, firefighters arriving during the morning of September 11, 2001, were similar in many ways to disaster survivors.10 In a paramilitary organization like FDNY, the loss of 343 coworkers could be particularly traumatic, a fact emphasized by our finding that “the loss of a coworker during the disaster” was an independent predictor of probable PTSD in all models, particularly strong in the baseline model.

Those with delayed-onset probable PTSD or delayed-onset WTC cough syndrome had more comorbid symptoms at baseline than the resilient group, suggesting that elevated symptom loads for one outcome could increase susceptibility for development of the other over time. Also, we noted the appearance of new symptoms of both WTC cough syndrome and probable PTSD years after the traumatic event, a finding with clinical implications. The strength and consistency of this relationship warrant screening for one outcome when the other is present and similarly warrant investigation into comorbid treatment, because lack of treatment of one condition may impede improvement or resolution of the other.

We found that WTC cough syndrome symptoms were associated with concurrently measured FEV1 % predicted at baseline and follow-up. These correlations, although small, were consistent in different analyses, and remained significant in multivariable analyses. Regarding WTC-exposed individuals, we found no other studies on the relationship between PTSD and pulmonary function. Regarding non-WTC studies, the relationship between PTSD and pulmonary function remains unclear. For example, in a group of asthmatics, no significant association was found between spirometry values and PTSD symptoms.28 Another study found a strong relationship between PTSD and asthma symptoms, and also reported a relationship between traumatic stress and pulmonary function.29 For these reasons, we plan additional studies.

Prior studies have shown relationships between PTSD and physical health ailments, including respiratory diseases,14‐16 as well as health-related quality of life.17,18 Chronic disease may increase vulnerability and the likelihood of PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Relationships between psychologic and physical illnesses such as asthma15,30 or GERD14 have also been reported. Possible physiologic explanations for the association between PTSD and asthma include, among others, altered inflammatory response,15 immune abnormalities,30 or low cortisol levels.31 It is also possible that certain respiratory symptoms could heighten or precipitate arousal symptoms, such as difficulty sleeping, unusual irritability, and increased anger in those firefighters who, pre-WTC, might have prided themselves on their physical abilities. Persistence of WTC-related respiratory symptoms might serve as constant reminders of the disaster, possibly making reexperiencing (one of three PTSD domains in the DSM-IV-TR) more likely.

Alternatively, symptoms of PTSD may have played a role in increasing physical symptoms.32 Some studies suggest that those with a history of PTSD are at increased risk of developing a wide range of physical diseases and symptoms,30 including asthma.15 Associations between the brain and gut have been postulated because the limbic system, a part of the brain responsible for emotionality and visceral pain transmission, is also responsible for controlling the gut.33 The nature of our cross-sectional data does not permit us to speculate as to which direction may be more likely, which we acknowledge as a study limitation.

The study had other potential limitations. First, our analytic cohort of 5,363 may not be representative of the entire population, but when comparing the cohort to those excluded, most factors were nearly identical (eg, proportion of most highly exposed) or comparable (eg, race/ethnicity). Probable PTSD and WTC cough syndrome were derived from symptom questionnaires, which, although sensitive, are not as specific as physician diagnoses. Symptom questionnaires may also be subject to recall bias. Multivariable regression results were not adjusted for multiple tests and therefore some of the apparently significant results must be considered tentative. Our screening tool for assessment of PTSD was based on the PCL-17, but the wording of questions and the answer formats were slightly different. However, this modified version had been used previously in the FDNY population,8,34,35 and was found to agree well with the PCL-17.24 We believe that a considerable strength of this study is our use of the same tool and method of administration at both time points, and reported prevalence estimates that were consistent with other studies.22 One final limitation is that we could not estimate the precise timing of delayed-onset symptoms, because of the time interval between baseline and follow-up questionnaires.

Conclusions

In FDNY WTC-exposed firefighters, a moderate association existed between commonly reported WTC cough syndrome and probable PTSD symptoms, which might warrant screening for one outcome when the other is present. Similarly, consideration should be given to the synergistic impact of treating both conditions (treatment of one condition may affect improvement of the other and conversely, lack of treatment of one may inhibit recovery in the other). Also, clinicians should be alert to the possibility of new symptoms presenting even years after the traumatic event. The concordance between WTC cough syndrome and PTSD symptoms was likely influenced, in part, by shared cofactors, including arrival during the collapse and longer WTC work duration. But it was also clear that WTC cough syndrome and probable PTSD are related, even when adjusting for these shared cofactors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Mr Niles had full access to all of the data in the study and takes full responsibility for the integrity of all of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Mr Niles: contributed to origination of the study, analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript.

Dr Webber: contributed to origination of the study, analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript.

Mr Gustave: contributed to data preparation, data analysis, and editing of the manuscript.

Dr Cohen: contributed to statistical expertise and editing of the manuscript.

Ms Zeig-Owens: contributed to data preparation, data analysis, and editing of the manuscript.

Dr Kelly: contributed to editing of the manuscript, particularly of the final draft.

Ms Glass: contributed to editing of the manuscript, particularly of the final draft.

Dr Prezant: contributed to origination of the study, analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Tables can be found in the Online Supplement at http://chestjournal.chestpubs.org/content/140/5/1146/suppl/DC1.

Abbreviations

- df

degrees of freedom

- DSM-IV-TR

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition, Text Revision)

- FDNY

New York City Fire Department

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disorder

- PCL

posttraumatic stress disorder checklist

- PCL-m

New York City Fire Department-modified posttraumatic stress disorder checklist

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

- WTC

World Trade Center

Footnotes

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [Grant R01-OH07350].

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (http://www.chestpubs.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml).

References

- 1.Landrigan PJ, Lioy PJ, Thurston G, et al. NIEHS World Trade Center Working Group Health and environmental consequences of the world trade center disaster. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(6):731–739. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prezant DJ, Weiden M, Banauch GI, et al. Cough and bronchial responsiveness in firefighters at the World Trade Center site. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(11):806–815. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herbert R, Moline J, Skloot G, et al. The World Trade Center disaster and the health of workers: five-year assessment of a unique medical screening program. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(12):1853–1858. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farfel M, DiGrande L, Brackbill R, et al. An overview of 9/11 experiences and respiratory and mental health conditions among World Trade Center Health Registry enrollees. J Urban Health. 2008;85(6):880–909. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9317-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webber MP, Gustave J, Lee R, et al. Trends in respiratory symptoms of firefighters exposed to the world trade center disaster: 2001-2005. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(6):975–980. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banauch GI, Alleyne D, Sanchez R, et al. Persistent hyperreactivity and reactive airway dysfunction in firefighters at the World Trade Center. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(1):54–62. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1329OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banauch GI, Hall C, Weiden M, et al. Pulmonary function after exposure to the World Trade Center collapse in the New York City Fire Department. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(3):312–319. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200511-1736OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corrigan M, McWilliams R, Kelly K, et al. FDNY World Trade Center Firefighters’ Mental health – computerized self-administered questionnaire to identify symptoms, PTSD & Counseling Service Use. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(suppl 3):S702–S709. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stellman JM, Smith RP, Katz CL, et al. Enduring mental health morbidity and social function impairment in world trade center rescue, recovery, and cleanup workers: the psychological dimension of an environmental health disaster. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(9):1248–1253. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galea S, Vlahov D, Resnick H, et al. Trends of probable post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(6):514–524. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, To T. Burden of comorbidity in individuals with asthma. Thorax. 2010;65(7):612–618. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.131078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brackbill RM, Hadler JL, DiGrande L, et al. Asthma and posttraumatic stress symptoms 5 to 6 years following exposure to the World Trade Center terrorist attack. JAMA. 2009;302(5):502–516. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz PP, Julian LJ, Omachi TA, et al. The impact of disability on depression among individuals with COPD. Chest. 2010;137(4):838–845. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauterbach D, Vora R, Rakow M. The relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder and self-reported health problems. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):939–947. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188572.91553.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Toole BI, Catts SV. Trauma, PTSD, and physical health: an epidemiological study of Australian Vietnam veterans. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagan J, Galea S, Ahern J, Bonner S, Vlahov D. Relationship of self-reported asthma severity and urgent health care utilization to psychological sequelae of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center among New York City area residents. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(6):993–996. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097334.48556.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beckham JC, Moore SD, Feldman ME, Hertzberg MA, Kirby AC, Fairbank JA. Health status, somatization, and severity of posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1565–1569. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schelling G, Stoll C, Haller M, et al. Health-related quality of life and posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(4):651–659. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199804000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. ATS/ERS Task Force Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at: 10th Annual Meeting of the International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies; October 24, 27, 1993; San Antonio, Texas. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perrin MA, DiGrande L, Wheeler K, Thorpe L, Farfel M, Brackbill R. Differences in PTSD prevalence and associated risk factors among World Trade Center disaster rescue and recovery workers. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1385–1394. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soo J, Webber MP, Gustave J, Lee R, Hall CB, Cohen HW, et al. Trends of Probable PTSD in Firefighters Exposed to the World Trade Center Disaster: 2001-2009. Dis Med andPubHealth Prep . In pressis. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2011.48. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boscarino JA, Adams RE. PTSD onset and course following the World Trade Center disaster: findings and implications for future research. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(10):887–898. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0011-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andrews B, Brewin CR, Stewart L, Philpott R, Hejdenberg J. Comparison of immediate-onset and delayed-onset posttraumatic stress disorder in military veterans. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118(4):767–777. doi: 10.1037/a0017203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buyantseva LV, Tulchinsky M, Kapalka GM, et al. Evolution of lower respiratory symptoms in New York police officers after 9/11: a prospective longitudinal study. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(3):310–317. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318032256e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayatbakhsh MR, Najman JM, Clavarino A, Bor W, Williams GM, O’Callaghan MJ. Association of psychiatric disorders, asthma and lung function in early adulthood. J Asthma. 2010;47(7):786–791. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2010.489141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzer C, Koch B, Grabe HJ, et al. Association of airflow limitation with trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder. Eur Respir J. 2011(37)(5):1068–1075. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00028010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boscarino JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and physical illness: results from clinical and epidemiologic studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1032:141–153. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yehuda R, Southwick SM, Nussbaum G, Wahby V, Giller EL, Jr, Mason JW. Low urinary cortisol excretion in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990;178(6):366–369. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199006000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simon GE, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(18):1329–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones MP, Dilley JB, Drossman D, Crowell MD. Brain-gut connections in functional GI disorders: anatomic and physiologic relationships. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(2):91–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berninger A, Webber MP, Cohen HW, et al. Trends of elevated PTSD risk in firefighters exposed to the World Trade Center disaster: 2001-2005. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(4):556–566. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berninger A, Webber MP, Niles JK, et al. Longitudinal study of probable post-traumatic stress disorder in firefighters exposed to the World Trade Center disaster. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53(12):1177–1185. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.