Abstract

Context:

KISS1 is a candidate gene for GnRH deficiency.

Objective:

Our objective was to identify deleterious mutations in KISS1.

Patients and Methods:

DNA sequencing and assessment of the effects of rare sequence variants (RSV) were conducted in 1025 probands with GnRH-deficient conditions.

Results:

Fifteen probands harbored 10 heterozygous RSV in KISS1 seen in less than 1% of control subjects. Of the variants that reside within the mature kisspeptin peptide, p.F117L (but not p.S77I, p.Q82K, p.H90D, or p.P110T) reduces inositol phosphate generation. Of the variants that lie within the coding region but outside the mature peptide, p.G35S and p.C53R (but not p.A129V) are predicted in silico to be deleterious. Of the variants that lie outside the coding region, one (g.1-3659C→T) impairs transcription in vitro, and another (c.1-7C→T) lies within the consensus Kozak sequence. Of five probands tested, four had abnormal baseline LH pulse patterns. In mice, testosterone decreases with heterozygous loss of Kiss1 and Kiss1r alleles (wild-type, 274 ± 99, to double heterozygotes, 69 ± 16 ng/dl; r2 = 0.13; P = 0.03). Kiss1/Kiss1r double-heterozygote males have shorter anogenital distances (13.0 ± 0.2 vs. 15.6 ± 0.2 mm at P34, P < 0.001), females have longer estrous cycles (7.4 ± 0.2 vs. 5.6 ± 0.2 d, P < 0.01), and mating pairs have decreased litter frequency (0.59 ± 0.09 vs. 0.71 ± 0.06 litters/month, P < 0.04) and size (3.5 ± 0.2 vs. 5.4 ± 0.3 pups/litter, P < 0.001) compared with wild-type mice.

Conclusions:

Deleterious, heterozygous RSV in KISS1 exist at a low frequency in GnRH-deficient patients as well as in the general population in presumably normal individuals. As in Kiss1+/−/Kiss1r+/− mice, heterozygous KISS1 variants in humans may work with other genetic and/or environmental factors to cause abnormal reproductive function.

Human puberty is triggered by the pulsatile secretion of GnRH from the hypothalamus to stimulate release of pituitary gonadotropins and, in turn, gonadal sex steroids. Patients with incomplete or absent puberty due to isolated GnRH deficiency (i.e. idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism) present a unique opportunity to identify the genetic factors that are responsible for awakening the reproductive endocrine cascade at puberty.

The last several years have seen an explosion in the identification of genes for GnRH deficiency. For every gene encoding a cell membrane-associated receptor implicated in the pathophysiology of GnRH deficiency, the gene encoding the corresponding ligand has also been found to harbor loss-of-function variants in hypogonadotropic patients. The genes encoding these receptor-ligand pairs include FGFR1/FGF8 (1, 2), PROKR2/PROK2 (3), TACR3/TAC3 (4), and most recently GNRHR/GNRH1 (5–8). Although mutations in PROKR2/PROK2 and TACR3/TAC3 were reported simultaneously (3–4), mutations in FGF8 were reported 4 yr after the initial reports of mutations in FGFR1 (1–2), and mutations in GNRH1 were reported 12 yr after mutations in GNRHR (5–8). The one exception to the if-receptor-then-ligand rule is the kisspeptin pathway: inactivating mutations in KISS1R (aka GPR54) were identified 7 yr ago (9, 10), but no mutations in KISS1 in patients with GnRH deficiency have been reported to date (11).

We therefore performed a systematic, large-scale evaluation of genetic variation in KISS1. First, we identified rare sequence variants (RSV) in KISS1 in a large cohort of patients with GnRH deficiency. After RSV were identified, we performed in vitro assays to evaluate their functional significance, particularly because some were found in unaffected family members as well as in presumably normal control subjects. Because some RSV were located outside of the mature kisspeptin peptide and therefore challenging to study in vitro, in silico prediction programs were used to evaluate their potential pathogenicity. All of the RSV that were identified were monoallelic and not biallelic; we therefore complemented these human studies with an examination of reproductive phenotypes in heterozygous and double-heterozygous Kiss1 and Kiss1r mice.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

A total of 1025 probands (688 men, 336 women, and one unspecified sex) with either congenital or acquired GnRH deficiency were examined. A total of 831 patients had congenital GnRH deficiency (413 with and 441 without anosmia, defined in Ref. 12), 89 women had hypothalamic amenorrhea (defined in Ref. 13), 62 patients had constitutional delay of puberty (absence of thelarche by 13 yr and/or menarche by 15 yr or testes <4 ml and/or no growth spurt by 14 yr, followed by eventual completion of pubertal development), and 19 men had serum testosterone of 101–279 ng/dl, that is, low but not in the frankly hypogonadal range. Two hundred Caucasian control subjects with normal reproductive function and sense of smell by history provided blood for DNA analysis. Data from 325 additional Caucasian control subjects was provided by M. Daly (personal communication). Whole-genome data from the 1000 Genomes Project reported in dbSNP build 133 provided additional control data from 178 subjects (14). The study was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Sequencing

The three exons of KISS1 (GenBank accession no. NM_002256.3) were sequenced in all probands and controls (12, 13). The 100 bp 5′ of the KISS1 transcription start site was also sequenced in 281 probands with normosmic GnRH deficiency and 200 controls. Probands found to carry RSV in KISS1 were also screened for mutations in the following genes for GnRH deficiency: GNRH1, GNRHR, FGF8, FGFR1, PROK2, PROKR2, TAC3, TACR3, KISS1R, KAL1, CHD7, and NELF. PolyPhen (15), MutationTaster (16), PMUT (17), and SIFT (18) were used to assess the functional significance of variants found.

Neuroendocrine phenotyping

Five probands were admitted to the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Clinical Research Center for an overnight 12-h, every 10-min sampling study to assess endogenous LH pulsatility, with measurement of FSH and sex steroids on study pools (19). Two subjects (4 and 13) also underwent 7-d studies with exogenous GnRH administration (19).

In vitro studies

Wild-type (WT) kisspeptin 68–121 and the variant S77I, Q82K, and P110T 54-amino-acid peptides as well as human kisspeptin 112–121 and the variant F117L decapeptide were synthesized by the MGH Peptide Core Laboratory. CHO cells stably expressing KISS1R were stimulated with 10−10 to 10−4 m WT or F117L decapeptides, and inositol phosphate (IP) accumulation was quantified (20). To test for dominant-negative activity, IP accumulation was quantified in CHO-KISS1R cells stimulated simultaneously with WT decapeptide 10−9 m and F117L decapeptide 10−9 to 10−4 m.

The WT 54-amino-acid kisspeptin and the S77I, Q82K, and P110T variants were compared in IP assays as described above as well as in a calcium mobilization assay. CHO-KISS1R cells were plated in a 96-well plate in serum-free medium for 2 h. Medium was replaced with 100 μl Fluo-4 NW dye loading solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and incubated for 30 min at 37 C. Cells were then treated with increasing concentrations of the WT, S77I, Q82K, or P110T 54-mers, and fluorescence was measured using a PolarStar fluorometer (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC). All experiments were done in triplicate and repeated in three independent studies.

To study the transcriptional activity of the WT and g.1-3659C→T KISS1 regulatory regions, DNA from −1702 to +60 bp of transcription start was PCR amplified from the genomic DNA of subject 1 and cloned into pGL3 Basic (Promega, Madison, WI). WT and mutant constructs were transiently transfected into HEK 293 cells using the Fugene reagent (Roche, South San Francisco, CA). After 24 h, cells were lysed using passive lysis buffer (Promega), and the luciferase assay system (Promega) was used to produce luminescence measured on a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA). Experiments were performed in at least quadruplicate and repeated in two independent studies.

Animals

Age-matched WT and mutant mice were generated in the 129S1/SvImJv background and housed as previously described (21). All procedures were approved by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care of MGH. Mice with nine different genotypes were analyzed: WT (+/+), Kiss1 heterozygotes (K+/−), Kiss1r (aka Gpr54) heterozygotes (G+/−), Kiss1 and Kiss1r double heterozygotes (K+/−G+/−), Kiss1 homozygotes (K−/−), Kiss1r homozygotes (G−/−), Kiss1 homozygotes/Kiss1r heterozygotes (K−/−G+/−), Kiss1 heterozygotes/Kiss1r homozygotes (K+/−G−/−), and Kiss1 and Kiss1r double homozygotes (K−/−G−/−).

All phenotypic assessments were done without knowledge of the genotype. Mice were inspected daily starting at postnatal d 21 (P21) for signs of sexual maturation (21). Animals were weighed, inspected, and then killed by asphyxiation with carbon dioxide at 12–16 wk (males) and 22–42 wk (females). WT and heterozygote females were in the estrous phase of the estrous cycle; homozygote females were either in estrus or diestrus. Blood was obtained before 1200 h by submandibular bleed and/or cardiac puncture. Reproductive organs were dissected and weighed, and sections were prepared, mounted, and stained by the Harvard Medical School Rodent Histopathology Core (for ovaries, serial sections every 150 μm).

Fertility

Mating cages were checked twice weekly and the presence of new litters noted. The number of pups per litter was counted at weaning; for some mating cages, pups were also counted at the time the litter was noted, and no significant difference was found (data not shown).

Hormone assays

FSH was measured using the FSH (rat) enzyme immunoassay (ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH). LH was measured by immunoradiometric assay and testosterone by RIA by the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction Ligand Assay and Analysis Core. Respective intraassay and interassay coefficients of variation were 5.5 and 7.7% for FSH, 3.9 and 6.7% for LH, and 3.4 and 8.1% for testosterone. Reportable ranges were 0.89–57 ng/ml for FSH, 0.04–37.4 ng/ml for LH, and 15–918 ng/dl for testosterone.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported in text and figures as mean ± sem. The frequency of rare KISS1 variants in patients vs. controls was compared using Fisher's exact test. Peptide activity in vitro was compared using two-way ANOVA. Luciferase activity produced by WT and mutant constructs was compared using an unpaired t test. For most mouse phenotypes, differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis using Tukey's method. Specific comparisons between WT and K+/−G+/− and between K−/− and K−/−G−/− were also assessed by unpaired t tests. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to analyze anogenital distance over time in WT and K+/−G+/− mice. Linear regression was performed for testosterone concentrations vs. number of intact Kiss1 and Kiss1r alleles. For hormone measurements, values above or below the reportable range were set at the upper or lower limit of the reportable range, respectively. All tests were two-tailed, and P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Identification of RSV

Of 1025 probands with GnRH-deficient conditions, 15 were found to carry heterozygous RSV in KISS1 that were seen in less than 1% of 525 control subjects and 178 subjects in the 1000 Genomes Project. Figure 1 summarizes the location and functional consequences of the variants, which are found throughout the KISS1 gene, with no obvious clustering of variants or mutational hotspots.

Fig. 1.

RSV identified in probands. A, Genomic organization of KISS1. Light blue rectangles, noncoding portions of exons; purple rectangles, coding portions of exons; dark blue lines, introns. B, Amino acid sequence of the KISS1 gene product in humans, cow, mouse, and rat. Light blue, signal peptide; blue, mature kisspeptin, with the active C-terminal amino acids in dark blue; line above, putative PEST sequence; asterisks, residues altered by sequence variants. C, Variants identified in subjects, with sequencing chromatographs, nucleotide and amino acid changes, predictions of functional consequences by in silico programs, and activity tested in vitro. ↓↓, Likely damaging; ↓, possibly damaging; ↔, benign; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

The RSV c.328C→A, p.P110T, has been reported in 14% of Han Chinese and 16% of Korean girls with normal puberty, respectively, but in 0% of African girls (22, 23). Thus, P110T appears to be an Asian polymorphism. The RSV c.268C→G, p.H90D was found in two African-American probands and in one control subject of unknown ethnicity. This variant has also been reported in the homozygous state in two of 77 Brazilian patients with central precocious puberty (11). One Caucasian control subject harbored an RSV, c.286G→C, p.A96V. Two of four prediction programs predicted this change to be deleterious.

Excluding p.P110T, the frequency of RSV in KISS1 was 12 in 1025 (1.2%) in individuals with GnRH-deficient conditions and three in 703 (0.4%) in control subjects (P = 0.12).

Phenotypes of probands with KISS1 RSV

Table 1 summarizes phenotypic characteristics of the 15 probands with KISS1 RSV. Seven had GnRH deficiency associated with anosmia, six were normosmic, and two had delayed puberty and hypothalamic amenorrhea. A variety of nonreproductive phenotypes were seen in probands, such as hearing loss, polydactyly, and leukodystrophy.

Table 1.

Subject genotypes and phenotypes

| Subject | Diagnosis | Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | Frequency in control subjects | Coding RSV in other genes | Additional phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | nIHH | g.1-3659C→T | 0/378 | None found | Impaired adrenal androgen production | |

| 2 | KS | g.1-3659C→T | 0/378 | KAL1 p.R191X/Y | Hypothyroidism; erosion of two ear bones | |

| 3 | CDP/HA | c.1−7 C→T | 0/378 | None found | Missing teeth, crowded teeth | |

| 4 | KS | c.1−7 C→T | 0/378 | None found | ||

| 5 | nIHH | c.103G→A | G35S | 0/703 | None found | Cleft lip, microphallus, bilateral cryptorchidism, Asperger's syndrome |

| 6 | nIHH | c.157C→T | C53R | 0/703 | FGFR1 p.G687R/+ | Preaxial polydactyly |

| 7 | Adult IHH/anosmia | c.230G→T | S77I | 0/703 | None found | Hysterical blindness |

| 8 | Adult IHH/anosmia | c.244C→A | Q82K | 0/703 | None found | Cryptorchidism, outpatient coronary disease, peripheral neuropathy |

| 9 | nIHH | c.268C→G | H90D | 1/703 | None found | Flat feet, foreshortened limbs |

| 10 | CDP/HA | c.268C→G | H90D | 1/703 | None found | |

| 11 | KS | c.328C→A | P110T | 0/703 | None found | Absent olfactory bulbs |

| 12 | KS | c.328C→A | P110T | 0/703 | None found | Hearing loss, missing teeth, microphallus, unilateral cryptorchidism |

| 13 | KS | c.328C→A | P110T | 0/703 | None found | Hearing loss, cryptorchidism, mosaic XXY |

| 14 | nIHH | c.349T→C | F117L | 1/703 | None found | Missing teeth, leukodystrophy, ataxia |

| 15 | nIHH | c.377C→T | A129V | 0/703 | None found |

CDP, Constitutional delay of puberty; HA, hypothalamic amenorrhea; KS, Kallmann syndrome; nIHH, normosmic idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.

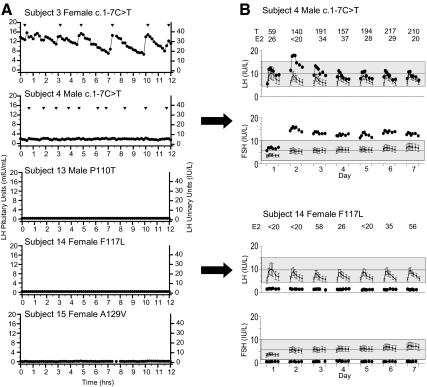

Detailed neuroendocrine phenotyping was available for five individuals, all but one of whom showed absent or very-low-amplitude LH pulses (Fig. 2). Subjects 4 and 14 also underwent treatment with exogenous pulsatile GnRH. Subject 4 (c.1-7C→T) showed a typical response to GnRH therapy, but subject 14 (p.F117L) failed to respond to exogenous GnRH, with LH, FSH, and estradiol levels remaining low throughout the study.

Fig. 2.

Neuroendocrine profiles of subjects with RSV in KISS1. A, Baseline secretory patterns of LH as determined by frequent sampling (every 10 min) for 12 h in subjects 3, 4, 15, 16, and 17. Arrowheads indicate pulses. B, Gonadotropin responses to 7 d pulsatile GnRH. The response to a single GnRH pulse (time = 0 to +2 h) was monitored each day. Daily sex-steroid levels are shown above the graphs. T, Testosterone, in ng/dl; E2, estradiol, in pg/ml.

Functional consequences of RSV

The effects of four variants that lie within the mature kisspeptin peptide (S77I, Q82K, P110T, and F117L) were studied in vitro. (The H90D variant has previously been shown to have activity indistinguishable from WT kisspeptin, Ref. 11). The F117L variant lies within the carboxyl-terminal decapeptide of kisspeptin, which is necessary and sufficient for activation of the kisspeptin receptor (24). The WT and F117L kisspeptin decapeptides were compared in their ability to stimulate IP accumulation in CHO-KISS1R cells (Fig. 3A). The EC50 for the WT decapeptide was 0.11 nm, whereas the EC50 of the F117L mutant was 200 nm. There was no evidence of antagonist or dominant-negative activity of the mutant F117L kisspeptin (Fig. 3A). Functional studies of mutant 54-amino-acid kisspeptins containing S77I, Q82K, or P110T did not show a significant change in Ca2+ release or IP accumulation compared with WT (data not shown). Although the S77I variant did not alter activation of the kisspeptin receptor, it alters a serine residue within a putative PEST sequence, a domain associated with rapid degradation of proteins (11).

Fig. 3.

Characterization of KISS1 variants in vitro. A, IP accumulation induced by WT or F117L kisspeptin decapeptide at doses from 10−10 to 10−4 m; B, transcriptional activity of WT and g.1-3659C→T kisspeptin regulatory regions. Data from a representative experiment are shown. CPM, Counts per minute; RLU, radioluminescent units; CMV, cytomegalovirus enhancer.

The variants that lie within the KISS1 coding region but outside the mature kisspeptin peptide were analyzed in silico. The c.103G→A (p.G35S) variant alters the last base pair of exon 2 and thus is strongly predicted to disrupt splicing between exons 2 and 3. The variant C53R is predicted to be inactivating by three of four computer prediction programs, and A129V is predicted to be inactivating by one of four programs.

The variants that lie outside the KISS1 coding region were also analyzed in vitro and in silico. The effect of the g.1-3659C→T variant on transcriptional efficiency was examined in HEK 293 cells transiently transfected with constructs containing the WT or variant KISS1 regulatory region fused to the luciferase gene. The g.1-3659C→T variant showed a 58% reduction in transcriptional efficiency compared with WT (Fig. 3B). The variant c.1-7C→T lies near the translation start site within the consensus Kozak sequence, a sequence that enhances translational efficiency, although the role of the −7 position has not been formally studied (25).

Pedigrees

Figure 4 shows the probands' pedigrees. Two probands were found to have other variants in genes implicated in GnRH deficiency. Subject 2 has a p.R191X nonsense mutation in KAL1. Subject 6 carries a p.G687R change in FGFR1. This variant affects a residue in the tyrosine kinase domain and is predicted in silico to be deleterious by four of four prediction programs.

Fig. 4.

Pedigrees of subjects with RSV in KISS1. Arrows indicate probands. HA, Hypothalamic amenorrhea; IHH, idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.

The p.F117L variant found in subject 14 was also found in the subject's mother, who had menarche at age 11 yr and who noted irregular menses until age 14–15 yr. On formal smell testing, she scored at less than the fifth percentile.

Phenotypes of male mouse heterozygotes

To test the hypothesis that heterozygous mutations in Kiss1 can cause reproductive deficits either alone or in combination with mutations in other genes, mice heterozygous for Kiss1 (K+/−), Kiss1r (also called Gpr54, G+/−), or both (K+/−G+/−) were studied. Kiss1/Kiss1r double-heterozygote mice had significantly shorter anogenital distances (an indicator of testosterone action) (21) than WT mice (at P34, 13.0 ± 0.2 vs. 15.6 ± 0.2 mm, P < 0.001, Fig. 5A). Serum testosterone concentrations decreased with increasing heterozygous loss of Kiss1 and Kiss1r alleles (WT 274 ± 99, K+/− 123 ± 28 ng/dl, G+/− 130 ± 77 ng/dl, K+/−G+/− 69 ± 16 ng/dl; r2 = 0.13; P = 0.03 for correlation between testosterone and number of mutant Kiss1 and/or Kiss1r alleles; Fig. 5, C and D). No differences in FSH or LH concentrations or testicular weights were seen (Fig. 5B and data not shown), nor was there a difference in seminiferous tubule diameter between WT and Kiss1/Kiss1r double-heterozygote mice (194 ± 2 μm, n = 4, vs. 196 ± 2 μm, n = 7; P = 0.5).

Fig. 5.

Phenotypes of male mutant mice. A, Anogenital distance (AGD) in male mice over time of 11 animals were in each group; B, combined weights of testes; C, serum testosterone; D, serum testosterone as a function of number of WT alleles. K+/−, Kiss1 heterozygote; G+/− Kiss1r (Gpr54) heterozygote; K+/−G+/−, Kiss1 and Kiss1r double heterozygote; K−/−, Kiss1 homozygote; G−/−, Kiss1r homozygote; K−/−G−/− Kiss1 and Kiss1r double homozygote. Columns and error bars show mean ± sem. *, P < 0.01 compared with WT; †, P < 0.01 compared with K−/−, as determined by two-way ANOVA; for clarity, not all differences are indicated. Columns in B and C with different letters (a, b, c) are statistically different by one-way ANOVA.

Phenotypes of female mouse heterozygotes

Kiss1/Kiss1r double-heterozygote female mice achieved vaginal opening at ages comparable to those of WT animals (Fig. 6A). However, daily vaginal smears revealed longer estrous cycles in Kiss1/Kiss1r double-heterozygote mice (WT 5.6 ± 0.2 d, K+/−G+/− 7.4 ± 0.2 d, P < 0.01; Fig. 6B). This difference was attributable to a longer estrous phase (WT 2.1 ± 0.1 d, K+/−G+/− 4.1 ± 0.2 d, P < 0.01; Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Phenotypes of female mutant mice and fertility of mutant mice. A, Percentage of female mice with vaginal opening (VO) over time. B, Length of estrous cycle. Daily vaginal smears were obtained over a period of 2–10 months. Mice in prolonged estrus (>10 d) were excluded. C, Length of estrous phase. D, Average number of litters per month for each mating pair. E, Average number of pups per litter. Genotype abbreviations as in Fig. 5. Columns and error bars show mean ± sem. Numbers indicate cycles or litters evaluated. Columns with different letters (a, b, c) are statistically different by one-way ANOVA. *, P < 0.01 compared with WT by one-way ANOVA.

Uterine weights of female double-heterozygote mice were indistinguishable from those of WT mice (204 ± 40 vs. 162 ± 12 g, P = 0.2). Ovarian histology revealed no difference in the number of corpora lutea between WT and double-heterozygote mice (WT 5.0 ± 0.8, n = 6; K+/− G+/− 6.1 ± 0.6, n = 7; P = 0.3). FSH and LH concentrations also did not differ between WT and double-heterozygote female mice (data not shown).

Fertility of heterozygote mice

Compared with WT mice and Kiss1 and Kiss1r single heterozygotes, the frequency of litters was lower for Kiss1/Kiss1r double-heterozygote mating pairs (WT 0.71 ± 0.06, G+/− 0.83 ± 0.06, K+/−G+/− 0.59 ± 0.09 litters/month; P < 0.05 for G+/− vs. K+/−G+/−; Fig. 6D). The number of pups per litter was significantly smaller in double-heterozygote crosses than in WT crosses (WT 5.4 ± 0.3, K+/−G+/− 3.5 ± 0.2, P < 0.001; Fig. 6E). The number of pups per litter was also smaller for single-heterozygote crosses (K+/− 4.2 ± 0.1, G+/− 4.0 ± 0.2, P < 0.05 for both groups compared with WT; Fig. 6E).

Double-homozygote phenotypes

Reproductive phenotypes of mice doubly homozygous for mutations in Kiss1 and Kiss1r were also examined because it had previously been observed that the reproductive deficit of Kiss1 homozygotes was less severe than that of Kiss1r homozygotes (21). Kiss1/Kiss1r double homozygotes were comparable to Kiss1r single homozygotes and significantly different from Kiss1 single homozygotes for anogenital distance and testicular weight in males (Fig. 5, A and B) and for timing of vaginal opening in females (Fig. 6A).

Discussion

This study identified RSV in KISS1, a likely candidate gene for GnRH deficiency given the identification of mutations in KISS1R (which encodes the kisspeptin receptor) in patients with GnRH deficiency (9, 10), the hypogonadotropic phenotypes of mice with targeted deletions of either Kiss1 or Kiss1r (24), and kisspeptin's powerful biological role in stimulating GnRH neurons (24). A number of RSV were identified, all heterozygous. None coded for a frameshift or premature termination codon, prompting the pursuit of additional in silico, in vitro, and in vivo studies to explore the functional consequences of these variants. The discovery of these RSV, some clearly deleterious, coupled with the finding of reproductive phenotypes in heterozygous Kiss1 mutant mice suggest that heterozygous RSV in KISS1 can contribute, albeit rarely, to the phenotype of GnRH deficiency, much the way that heterozygous RSV in PROK2, PROKR2, TAC3, TACR3, CHD7, and WDR11 have been associated with GnRH-deficient phenotypes (3, 26–31).

Of the 10 KISS1 RSV that were identified in this study, some were clearly deleterious and some were not. Located within the C-terminal decapeptide, where the biological activity of kisspeptin resides, the p.F117L change is clearly inactivating in vitro. Located within the parent protein but outside of the mature kisspeptin peptide, c.103G→A (p.G35S), is strongly predicted to disrupt pre-mRNA splicing and therefore is almost certainly deleterious. Located outside of the coding sequence, the variant g.1-3659C→T lies in a cAMP response element and impairs transcription in vitro.

Other variants revealed potential mechanisms of pathogenicity that were not formally tested. The variant c.1-7C→T is located within the Kozak consensus sequence and may impair translation. Mutagenesis of several positions within the Kozak sequence has been shown to reduce translation, but manipulations at position −7 have not been reported (25). S77I alters a serine residue within a PEST sequence, known to be involved in the rapid degradation of proteins (11). A PEST variant could potentially impact kisspeptin signaling by slowing kisspeptin degradation, prolonging occupation of KISS1R and causing desensitization, thereby impairing GnRH secretion.

The rarity of variants makes it difficult to demonstrate statistically that KISS1 mutations cause GnRH deficiency in humans. We did not observe a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of the total number of KISS1 variants in patients vs. controls; to do so would require roughly twice the number of control subjects. Similarly, for any single variant, to demonstrate a difference in prevalence between patients and controls would require data for approximately 2000 control subjects (32). Although our current data are unable to resolve these differences, such analyses will soon be able to be performed as large-scale data from whole-exome and whole-genome studies become available.

Thus, even for the variants demonstrated to be deleterious, the question remains: do these heterozygous variants contribute to the GnRH deficiency phenotype? The word “contribute” is used instead of “cause” because mutations in more than one gene have been found in individual patients with GnRH deficiency, leading the previous traditional monogenic status of this disorder to be supplanted by an oligogenic framework (3, 33). Thus, the burden of disease causation no longer falls on a single gene but rather on multigene networks that control GnRH secretion. As a result, the contribution of heterozygous mutations is being increasingly recognized, even in the absence of clear familial segregation. For example, the gene encoding the prokineticin receptor, PROKR2, is a rich source of mutations in GnRH deficiency, the overwhelming majority of which are heterozygous (monoallelic) as opposed to homozygous or compound heterozygous (biallelic) (27, 28). Similarly, patients carrying mutations in the neurokinin B receptor (encoded by TACR3), another G protein-coupled receptor, frequently appear to carry only heterozygous mutations (30).

Moving beyond the precedents established by other genes for GnRH deficiency, heterozygous KISS1 mutations could cause GnRH-deficient states through a number of mechanisms. There is evidence that monoallelic expression of genes is more widespread than previously appreciated (34). If this is true for KISS1 in relevant cells (e.g. hypothalamic neurons), a heterozygous mutation in the allele that is expressed could act as a second hit leading to loss of both alleles. Alternatively, heterozygous KISS1 variants may act in concert with other genetic factors to bring about GnRH deficiency. This oligogenic model could account for several observations: 1) the presence of heterozygous KISS1 variants in unaffected family members, who presumably do not carry the other genetic factors working with KISS1 to cause GnRH deficiency; 2) the range of reproductive phenotypes seen in subjects carrying KISS1 variants, from transient to permanent forms of GnRH deficiency; and 3) the presence of nonreproductive phenotypes such as anosmia, leukodystrophy, polydactyly, and hearing loss. These phenotypes would not necessarily be expected to be seen with KISS1 mutations alone, because mice with Kiss1 mutations and humans and mice with KISS1R/Kiss1r mutations have not been reported to have phenotypes beyond hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (9, 10, 21), and could be due to effects of other genetic factors (12, 28). This could also account for subject 13's pituitary resistance to GnRH, which would not be expected with loss of KISS1 function but does not preclude the presence of a concomitant hypothalamic defect.

Using a mouse model to test the hypothesis that heterozygous mutations in KISS1 can contribute to GnRH deficiency, we found that heterozygous Kiss1 mutations can indeed produce reproductive phenotypes and that these phenotypes are further accentuated by heterozygous mutations in Kiss1r. Given the rarity of variants in KISS1 and KISS1R, it is unlikely that an individual carrying mutations in both genes will be found. It would be more likely for KISS1 variants to act in concert with other genes for GnRH deficiency in which variants are more common. Indeed, two probands with KISS1 variants in this study harbor variants in other genes for GnRH deficiency: KAL1 (subject 2) and FGFR1 (subject 6). Although a hemizygous mutation in KAL1 is generally sufficient to cause Kallmann syndrome in male patients, subject 2's father is inferred to carry the same KAL1 mutation (because he had a granddaughter through another union with the same KAL1 mutation), yet he fathered several children. Thus, the proband's KISS1 variant may have acted in combination with the KAL1 mutation to cause GnRH deficiency. Interactions between GnRH-deficiency genes could be further tested using a variety of mouse models that mirror human GnRH deficiency (26, 35, 36).

The rarity of KISS1 variants is striking and echoes the rarity of mutations in KISS1R (12). Many genes for GnRH deficiency harbor mutations at much higher frequencies in GnRH-deficient patients: 5% in TACR3 (29, 30), 4% in GNRHR (12, 37), 4% in PROKR2 (3, 27), 5–14% in KAL1 (12, 38, 39), and 7–10% in FGFR1 (1, 40, 41). Thus, when attempting to identify the genetic basis of a patient's GnRH deficiency, it may be reasonable to prioritize sequencing of genes more likely to carry mutations over screening KISS1/KISS1R. Given oligogenicity, however, identifying a mutation in one gene does not preclude the presence of mutations in a second gene.

Why nucleotide variants/mutations in both KISS1 and KISS1R are so rare is puzzling. It is possible that variants in the kisspeptin pathway are not promulgated in families because this ligand-receptor pair contributes to a diverse range of critical cellular activities from conception to grave. Kisspeptin is secreted in great quantities throughout pregnancy (42) and inhibits trophoblast invasion in cell culture (43). Kisspeptin may therefore play an important role in embryonic implantation. Furthermore, kisspeptin is also known by the name metastin, based on its ability to limit the metastatic potential of melanoma and breast-cancer cell lines (44, 45). Therefore, mutations in KISS1 and KISS1R may be rare because kisspeptin's roles in placentation and/or metastasis suppression create negative selection pressure against the transmission of inactivating variants within families.

Rare variants in KISS1 can be associated with GnRH-deficient states and, as demonstrated by the mouse studies herein, may work in combination with other genetic factors to bring about reproductive phenotypes. As data emerge from large-scale genomic studies, it may soon be possible to determine which variants are common polymorphisms and which are likely to be pathological. Similarly, genomic studies of patients with GnRH deficiency may identify the gene mutations that may work in combination with KISS1 to cause GnRH deficiency. Demanding the identification of homozygous, loss-of-function mutations in a candidate gene as proof of that gene's contribution to disease may cause genes with important physiological functions to be overlooked.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. L. Jameson and J. Weiss for assistance in obtaining DNA samples, P. B. Kaplowitz for referring a research subject, W. F. Crowley, Jr., for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript, and M. Daly for supplying data from 325 control subjects.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01 HD015788 (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NICHD), M01-RR-01066 (Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, from the National Center for Research Resources), T32 DK007529 (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders), U54 HD028138 (through cooperative agreement as part of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research, NICHD), and K12 HD051959 (as part of the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health program, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, HICHD, and Office of the Director).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- IP

- Inositol phosphate

- P21

- postnatal d 21

- RSV

- rare sequence variants

- WT

- wild type.

References

- 1. Dodé C, Levilliers J, Dupont JM, De Paepe A, Le Dû N, Soussi-Yanicostas N, Coimbra RS, Delmaghani S, Compain-Nouaille S, Baverel F, Pêcheux C, Le Tessier D, Cruaud C, Delpech M, Speleman F, Vermeulen S, Amalfitano A, Bachelot Y, Bouchard P, Cabrol S, Carel JC, Delemarre-van de Waal H, Goulet-Salmon B, Kottler ML, Richard O, Sanchez-Franco F, Saura R, Young J, Petit C, Hardelin JP. 2003. Loss-of-function mutations in FGFR1 cause autosomal dominant Kallmann syndrome. Nat Genet 33:463–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Falardeau J, Chung WC, Beenken A, Raivio T, Plummer L, Sidis Y, Jacobson-Dickman EE, Eliseenkova AV, Ma J, Dwyer A, Quinton R, Na S, Hall JE, Huot C, Alois N, Pearce SH, Cole LW, Hughes V, Mohammadi M, Tsai P, Pitteloud N. 2008. Decreased FGF8 signaling causes deficiency of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in humans and mice. J Clin Invest 118:2822–2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dodé C, Teixeira L, Levilliers J, Fouveaut C, Bouchard P, Kottler ML, Lespinasse J, Lienhardt-Roussie A, Mathieu M, Moerman A, Morgan G, Murat A, Toublanc JE, Wolczynski S, Delpech M, Petit C, Young J, Hardelin JP. 2006. Kallmann syndrome: mutations in the genes encoding prokineticin-2 and prokineticin receptor-2. PLoS Genet 2:e175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Topaloglu AK, Reimann F, Guclu M, Yalin AS, Kotan LD, Porter KM, Serin A, Mungan NO, Cook JR, Ozbek MN, Imamoglu S, Akalin NS, Yuksel B, O'Rahilly S, Semple RK. 2009. TAC3 and TACR3 mutations in familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism reveal a key role for Neurokinin B in the central control of reproduction. Nat Genet 41:354–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Roux N, Young J, Misrahi M, Genet R, Chanson P, Schaison G, Milgrom E. 1997. A family with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and mutations in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. N Engl J Med 337:1597–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Layman LC, Cohen DP, Jin M, Xie J, Li Z, Reindollar RH, Bolbolan S, Bick DP, Sherins RR, Duck LW, Musgrove LC, Sellers JC, Neill JD. 1998. Mutations in gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene cause hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Nat Genet 18:14–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bouligand J, Ghervan C, Tello JA, Brailly-Tabard S, Salenave S, Chanson P, Lombès M, Millar RP, Guiochon-Mantel A, Young J. 2009. Isolated familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and a GNRH1 mutation. N Engl J Med 360:2742–2748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chan YM, de Guillebon A, Lang-Muritano M, Plummer L, Cerrato F, Tsiaras S, Gaspert A, Lavoie HB, Wu CH, Crowley WF, Jr, Amory JK, Pitteloud N, Seminara SB. 2009. GNRH1 mutations in patients with idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:11703–11708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Roux N, Genin E, Carel JC, Matsuda F, Chaussain JL, Milgrom E. 2003. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:10972–10976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Thresher RR, Acierno JS, Jr, Shagoury JK, Bo-Abbas Y, Kuohung W, Schwinof KM, Hendrick AG, Zahn D, Dixon J, Kaiser UB, Slaugenhaupt SA, Gusella JF, O'Rahilly S, Carlton MB, Crowley WF, Jr, Aparicio SA, Colledge WH. 2003. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N Engl J Med 349:1614–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Silveira LG, Noel SD, Silveira-Neto AP, Abreu AP, Brito VN, Santos MG, Bianco SD, Kuohung W, Xu S, Gryngarten M, Escobar ME, Arnhold IJ, Mendonca BB, Kaiser UB, Latronico AC. 2010. Mutations of the KISS1 gene in disorders of puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:2276–2280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sykiotis GP, Plummer L, Hughes VA, Au M, Durrani S, Nayak-Young S, Dwyer AA, Quinton R, Hall JE, Gusella JF, Seminara SB, Crowley WF, Jr, Pitteloud N. 2010. Oligogenic basis of isolated gonadotropin-releasing hormone deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:15140–15144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caronia LM, Martin C, Welt CK, Sykiotis GP, Quinton R, Thambundit A, Avbelj M, Dhruvakumar S, Plummer L, Hughes VA, Seminara SB, Boepple PA, Sidis Y, Crowley WF, Jr, Martin KA, Hall JE, Pitteloud N. 2011. A genetic basis for functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. N Engl J Med 364:215–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DL, Auton A, Brooks LD, Gibbs RA, Hurles ME, McVean GA. 2010. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 467:1061–1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ramensky V, Bork P, Sunyaev S. 2002. Human non-synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res 30:3894–3900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schwarz JM, Rödelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. 2010. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods 7:575–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferrer-Costa C, Gelpí JL, Zamakola L, Parraga I, de la Cruz X, Orozco M. 2005. PMUT: a web-based tool for the annotation of pathological mutations on proteins. Bioinformatics 21:3176–3178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. 2009. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc 4:1073–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dwyer AA, Hayes FJ, Plummer L, Pitteloud N, Crowley WF., Jr 2010. The long-term clinical follow-up and natural history of men with adult-onset idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:4235–4243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuohung W, Burnett M, Mukhtyar D, Schuman E, Ni J, Crowley WF, Glicksman MA, Kaiser UB. 2010. A high-throughput small-molecule ligand screen targeted to agonists and antagonists of the G-protein-coupled receptor GPR54. J Biomol Screen 15:508–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lapatto R, Pallais JC, Zhang D, Chan YM, Mahan A, Cerrato F, Le WW, Hoffman GE, Seminara SB. 2007. Kiss1−/− mice exhibit more variable hypogonadism than Gpr54−/− mice. Endocrinology 148:4927–4936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Luan X, Zhou Y, Wang W, Yu H, Li P, Gan X, Wei D, Xiao J. 2007. Association study of the polymorphisms in the KISS1 gene with central precocious puberty in Chinese girls. Eur J Endocrinol 157:113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ko JM, Lee HS, Hwang JS. 2010. KISS1 gene analysis in Korean girls with central precocious puberty: a polymorphism, p.P110T, suggested to exert a protective effect. Endocr J 57:701–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pineda R, Aguilar E, Pinilla L, Tena-Sempere M. 2010. Physiological roles of the kisspeptin/GPR54 system in the neuroendocrine control of reproduction. Prog Brain Res 181:55–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kozak M. 1986. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell 44:283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pitteloud N, Zhang C, Pignatelli D, Li JD, Raivio T, Cole LW, Plummer L, Jacobson-Dickman EE, Mellon PL, Zhou QY, Crowley WF., Jr 2007. Loss-of-function mutation in the prokineticin 2 gene causes Kallmann syndrome and normosmic idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:17447–17452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cole LW, Sidis Y, Zhang C, Quinton R, Plummer L, Pignatelli D, Hughes VA, Dwyer AA, Raivio T, Hayes FJ, Seminara SB, Huot C, Alos N, Speiser P, Takeshita A, Van Vliet G, Pearce S, Crowley WF, Jr, Zhou QY, Pitteloud N. 2008. Mutations in prokineticin 2 and prokineticin receptor 2 genes in human gonadotrophin-releasing hormone deficiency: molecular genetics and clinical spectrum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:3551–3559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sarfati J, Guiochon-Mantel A, Rondard P, Arnulf I, Garcia-Piñero A, Wolczynski S, Brailly-Tabard S, Bidet M, Ramos-Arroyo M, Mathieu M, Lienhardt-Roussie A, Morgan G, Turki Z, Bremont C, Lespinasse J, Du Boullay H, Chabbert-Buffet N, Jacquemont S, Reach G, De Talence N, Tonella P, Conrad B, Despert F, Delobel B, Brue T, Bouvattier C, Cabrol S, Pugeat M, Murat A, Bouchard P, Hardelin JP, Dodé C, Young J. 2010. A comparative phenotypic study of kallmann syndrome patients carrying monoallelic and biallelic mutations in the prokineticin 2 or prokineticin receptor 2 genes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:659–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Young J, Bouligand J, Francou B, Raffin-Sanson ML, Gaillez S, Jeanpierre M, Grynberg M, Kamenicky P, Chanson P, Brailly-Tabard S, Guiochon-Mantel A. 2010. TAC3 and TACR3 defects cause hypothalamic congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:2287–2295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gianetti E, Tusset C, Noel SD, Au MG, Dwyer AA, Hughes VA, Abreu AP, Carroll J, Trarbach E, Silveira LF, Costa EM, de Mendonça BB, de Castro M, Lofrano A, Hall JE, Bolu E, Ozata M, Quinton R, Amory JK, Stewart SE, Arlt W, Cole TR, Crowley WF, Kaiser UB, Latronico AC, Seminara SB. 2010. TAC3/TACR3 mutations reveal preferential activation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone release by neurokinin B in neonatal life followed by reversal in adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:2857–2867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim HG, Ahn JW, Kurth I, Ullmann R, Kim HT, Kulharya A, Ha KS, Itokawa Y, Meliciani I, Wenzel W, Lee D, Rosenberger G, Ozata M, Bick DP, Sherins RJ, Nagase T, Tekin M, Kim SH, Kim CH, Ropers HH, Gusella JF, Kalscheuer V, Choi CY, Layman LC. 2010. WDR11, a WD protein that interacts with transcription factor EMX1, is mutated in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and Kallmann syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 87:465–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Collins JS, Schwartz CE. 2002. Detecting polymorphisms and mutations in candidate genes. Am J Hum Genet 71:1251–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pitteloud N, Quinton R, Pearce S, Raivio T, Acierno J, Dwyer A, Plummer L, Hughes V, Seminara S, Cheng YZ, Li WP, Maccoll G, Eliseenkova AV, Olsen SK, Ibrahimi OA, Hayes FJ, Boepple P, Hall JE, Bouloux P, Mohammadi M, Crowley W. 2007. Digenic mutations account for variable phenotypes in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Invest 117:457–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gimelbrant A, Hutchinson JN, Thompson BR, Chess A. 2007. Widespread monoallelic expression on human autosomes. Science 318:1136–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chung WC, Moyle SS, Tsai PS. 2008. Fibroblast growth factor 8 signaling through fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is required for the emergence of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology 149:4997–5003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matsumoto S, Yamazaki C, Masumoto KH, Nagano M, Naito M, Soga T, Hiyama H, Matsumoto M, Takasaki J, Kamohara M, Matsuo A, Ishii H, Kobori M, Katoh M, Matsushime H, Furuichi K, Shigeyoshi Y. 2006. Abnormal development of the olfactory bulb and reproductive system in mice lacking prokineticin receptor PKR2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:4140–4145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bhagavath B, Ozata M, Ozdemir IC, Bolu E, Bick DP, Sherins RJ, Layman LC. 2005. The prevalence of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor mutations in a large cohort of patients with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Fertil Steril 84:951–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bhagavath B, Xu N, Ozata M, Rosenfield RL, Bick DP, Sherins RJ, Layman LC. 2007. KAL1 mutations are not a common cause of idiopathic hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism in humans. Mol Hum Reprod 13:165–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Albuisson J, Pecheux C, Carel JC, Lacombe D, Leheup B, Lapuzina P, Bouchard P, Legius E, Matthijs G, Wasniewska M, Delpech M, Young J, Hardelin JP, Dode C. 2005. Kallmann syndrome: 14 novel mutations in KAL1 and FGFR1 (KAL2). Hum Mutat 25:98–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pitteloud N, Meysing A, Quinton R, Acierno JS, Jr., Dwyer AA, Plummer L, Fliers E, Boepple P, Hayes F, Seminara S, Hughes VA, Ma J, Bouloux P, Mohammadi M, Crowley WF., Jr 2006. Mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 cause Kallmann syndrome with a wide spectrum of reproductive phenotypes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 254–255:60–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Trarbach EB, Costa EM, Versiani B, de Castro M, Baptista MT, Garmes HM, de Mendonca BB, Latronico AC. 2006. Novel fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 mutations in patients with congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with and without anosmia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4006–4012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Horikoshi Y, Matsumoto H, Takatsu Y, Ohtaki T, Kitada C, Usuki S, Fujino M. 2003. Dramatic elevation of plasma metastin concentrations in human pregnancy: metastin as a novel placenta-derived hormone in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:914–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bilban M, Ghaffari-Tabrizi N, Hintermann E, Bauer S, Molzer S, Zoratti C, Malli R, Sharabi A, Hiden U, Graier W, Knöfler M, Andreae F, Wagner O, Quaranta V, Desoye G. 2004. Kisspeptin-10, a KiSS-1/metastin-derived decapeptide, is a physiological invasion inhibitor of primary human trophoblasts. J Cell Sci 117:1319–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee JH, Welch DR. 1997. Suppression of metastasis in human breast carcinoma MDA-MB-435 cells after transfection with the metastasis suppressor gene, KiSS-1. Cancer Res 57:2384–2387 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Miele ME, Robertson G, Lee JH, Coleman A, McGary CT, Fisher PB, Lugo TG, Welch DR. 1996. Metastasis suppressed, but tumorigenicity and local invasiveness unaffected, in the human melanoma cell line MelJuSo after introduction of human chromosomes 1 or 6. Mol Carcinog 15:284–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]