Abstract

Unlike cytotoxic agents that indiscriminately affect rapidly dividing cells, newer antineoplastic agents such as targeted therapies and immunotherapies are associated with thyroid dysfunction. These include tyrosine kinase inhibitors, bexarotene, radioiodine-based cancer therapies, denileukin diftitox, alemtuzumab, interferon-α, interleukin-2, ipilimumab, tremelimumab, thalidomide, and lenalidomide. Primary hypothyroidism is the most common side effect, although thyrotoxicosis and effects on thyroid-stimulating hormone secretion and thyroid hormone metabolism have also been described. Most agents cause thyroid dysfunction in 20%–50% of patients, although some have even higher rates. Despite this, physicians may overlook drug-induced thyroid dysfunction because of the complexity of the clinical picture in the cancer patient. Symptoms of hypothyroidism, such as fatigue, weakness, depression, memory loss, cold intolerance, and cardiovascular effects, may be incorrectly attributed to the primary disease or to the antineoplastic agent. Underdiagnosis of thyroid dysfunction can have important consequences for cancer patient management. At a minimum, the symptoms will adversely affect the patient’s quality of life. Alternatively, such symptoms can lead to dose reductions of potentially life-saving therapies. Hypothyroidism can also alter the kinetics and clearance of medications, which may lead to undesirable side effects. Thyrotoxicosis can be mistaken for sepsis or a nonendocrinologic drug side effect. In some patients, thyroid disease may indicate a higher likelihood of tumor response to the agent. Both hypothyroidism and thyrotoxicosis are easily diagnosed with inexpensive and specific tests. In many patients, particularly those with hypothyroidism, the treatment is straightforward. We therefore recommend routine testing for thyroid abnormalities in patients receiving these antineoplastic agents.

Cytotoxic agents, which affect any rapidly dividing cell, and endocrine agents, which act as agonists or antagonists on endocrine receptors present in cancers arising from hormone-responsive tissues, were the cornerstones of early cancer therapy. A new group of anticancer agents became available with the development of immunotherapies, agents that enhance recognition and destruction of cancer cells by the host’s immune system. Since around 1990, targeted therapies that inhibit specific cellular processes required for cancer cell growth and survival have been introduced.

Many cancer patients are at risk of developing thyroid dysfunction [reviewed in detail in (1–3)]. For example, iodinated contrast can be associated with acute effects on the thyroid, including hyperthyroidism in the presence of autonomous nodules or mild Graves disease, or transient hypothyroidism in patients with Hashimoto thyroiditis (1,2). Radiation therapy can be associated with hypothyroidism from direct effects on the thyroid or secondary to hypopituitarism from brain irradiation, which probably explains most of the increased incidence of hypothyroidism after bone marrow or stem cell transplants (3,4). Childhood irradiation has also been associated with the development of thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer (5).

Cytotoxic agents are rarely associated with thyroid abnormalities in the absence of irradiation. However, they may sensitize the thyroid gland to the effects of concomitant radiation therapy, increasing the risk of radiation-induced primary hypothyroidism (6). Some agents such as mitotane, 5-fluorouracil, estrogens, tamoxifen, podophyllin, and L-asparaginase alter levels of thyroid hormone–binding proteins without clinical significance (7–14). Other agents such as lomustine, vincristine, and cisplatin have in vitro effects on the thyroid (15–17), without obvious clinical impact.

In contrast to cytotoxic agents, novel antineoplastic agents such as targeted therapies and immunotherapies more specifically target signaling pathways in cancer cells but frequently have adverse effects on the thyroid gland. The symptoms of these effects can adversely affect patient’s quality of life but are easily diagnosed and treated, and a key to their detection is considering thyroid dysfunction in the differential diagnosis of a patient with relevant symptoms.

Importance of Assessing Thyroid Function in Cancer Patients

Identifying thyroid disease can be difficult in cancer patients but may have important consequences. Many of the symptoms of hypothyroidism such as fatigue and constipation are common in cancer patients and can be difficult to distinguish from symptoms attributable to the underlying malignancy, antineoplastic treatment, or medications used for symptom control (18,19). Symptoms of thyroid disease can also be confused with treatment-related toxic effects, leading to dose reductions or changes in treatment, or with other complications such as sepsis, leading to misguided treatment strategies. Unrecognized hypothyroidism or thyrotoxicosis may affect the metabolism of other medications (20). Finally, although rare, thyroid dysfunction can lead to life-threatening consequences in the cancer patient—sunitinib-induced hypothyroidism has been associated with myxedema coma (21) and cardiac compromise (22,23).

Some reports have found that development of thyroid dysfunction may be a marker for increased likelihood of response to therapy. For example, in patients with renal cell cancer, occurrence of remission and overall survival in patients treated with sorafenib or sunitinib was better in those who developed hypothyroidism than in those who did not (24,25). Thyroid autoimmunity is also associated with an improved tumor response to interleukin 2 (IL-2) therapy for melanoma (26) and renal cell cancer (27–29). Studies of ipilimumab have shown that the presence of immune-related adverse events, including hypophysitis, is associated with tumor regression (30), and several explanations for such an association can be proposed. First, bias may occur because of longer exposure to the agent in patients who respond to treatment, which may also increase the risk of developing thyroid disease. This has been shown for IL-2 (31). Second, for ipilimumab, the occurrence of autoimmunity is likely a marker of release of the immune system from its physiological control of self versus nonself recognition, indicating that the therapeutic goal is being achieved. Third, hypothyroidism may be beneficial in cancer patients. For example, development of hypothyroidism after head and neck irradiation was associated with improved survival (32). Hypothyroidism has also been associated with improved survival in patients with glioma (33) as well as a lower cancer risk and more indolent disease in patients with breast cancer (34). Although the mechanism is unknown, one hypothesis is that hypothyroidism could reduce antineoplastic drug metabolism, leading to higher drug levels and hence possibly increased efficacy. Alternatively, it has also been suggested that thyroid hormone itself can lead to tumor growth (35,36) and that its absence can deprive the tumor of a needed stimulus. Because of the proposed link between hypothyroidism and improved cancer outcomes, some concerns have been expressed about treating hypothyroidism in cancer patients (37,38). However, there is no prospective evidence that treating hypothyroidism worsens cancer outcomes, and, indeed, some studies suggest a protective role of thyroid hormone in certain cancers (39).

In patients receiving any of the agents to be discussed in this review, the clinician should have a high level of suspicion for thyroid disease when the patients are diagnosed with symptoms consistent with thyrotoxicosis or hypothyroidism. For thyrotoxicosis, symptoms include palpitations, weight loss, heat intolerance, frequent bowel movements, tremor, proximal muscle weakness, tachycardia, lid retraction or lid lag, insomnia, irritability, and fever. For hypothyroidism, symptoms include fatigue, weight gain, dry skin or dry hair, brittle nails, constipation, bradycardia, and hypothermia. In addition, for hypophysitis, headache and symptoms relating to other hormonal deficiencies can also be seen.

The purpose of this review is to call attention to the many off-target effects of novel antineoplastic agents that can cause thyroid dysfunction. We will describe currently recognized thyroid-related side effects of these agents, specifically, the frequency, clinical presentation, and possible underlying mechanisms. In addition, we provide recommendations for monitoring thyroid function during treatment with these agents and suggest appropriate treatment.

Methods

Data were collected by searching Medline. Search terms included names of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved novel antineoplastic agents and words relating to the thyroid gland (including “thyroid,” “hypothyroidism,” “hyperthyroidism,” “thyrotoxicosis,” and “Graves”). Certain non–FDA-approved agents with well-described thyroid effects were also included. Abstracts were assessed for relevance, and pertinent articles were reviewed in full. Articles describing the efficacy of these agents in thyroid cancer were excluded. Reference lists in the retrieved articles were also searched. Only English language articles were included. The compounds’ FDA-approved labeling was also examined for mention of thyroid side effects. The listed recommendations (Table 1) were based on published recommendations when available. Otherwise, they were based on the authors’ clinical experience. In making our recommendations, we placed a high priority on identifying thyroid disease early in its course to prevent adverse consequences on patients’ quality of life or inappropriate decisions regarding their therapy.

Table 1.

Novel antineoplastic agents, their mechanisms of action, indications, thyroid effects, and proposed screening for thyroid dysfunction*

| Agent | Mechanism of anticancer action | Main indications | Likely mechanism of effect on thyroid | Clinical manifestations | Average time from first exposure to onset | Frequency of thyroid dysfunction | Proposed screening |

| Hypothyroidism | |||||||

| Primary hypothyroidism | |||||||

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors: imatinib, sunitinib, sorefanib, motesanib, dasatinib, nilotinib, axitinib, and cediranib | ATP analogs that inhibit the action of tyrosine kinases | CML, GIST, renal cell cancer, hepatocellular cancer, investigational in other cancers | Preexisting LT4 therapy: imatinib, sorefanib, motesanib increase metabolism of LT4 (perhaps via type 3 deiodinase) | Increased LT4 requirement in athyreotic patients | Less than 2 wk | 21%–100% | TSH before treatment. Monitor TSH every 4 wk and titrate LT4 as required. Once TSH and dose are stable, monitor TSH every 2 mo. For imatinib, consider doubling dose of LT4 on initiation of therapy. |

| Previously euthyroid patients: sunitinib, sorafenib, dasatinib, nilotinib, axitinib and cediranib: Capillary regression leading to inadequate vascularity and acute or subacute gland destruction; possible direct effects on thyrocyte. | Hypothyroidism, occasionally preceded by mild thyrotoxicosis because of destructive thyroiditis†. | 4–16 wk for sorafenib, 4–94 wk for sunitinib | 18%–85%, less common with sorafenib and nilotinib than with other agents | TSH before treatment and then every month for the first 4 mo, then every 2–3 mo. | |||

| Denileukin diftitox | Ligand-binding domain of IL-2 linked with diphtheria toxin, allowing targeted delivery of toxin to lymphocytes | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, investigational for NHL and GVHD | Cytokine release from intrathyroidal lymphocytes or into general circulation from tumor cells leading to thyrocyte destruction | Thyroiditis, with initial thyrotoxicosis followed by hypothyroidism†. | 1––2 mo | Unknown, one case series only | TSH and anti-TPO antibodies before treatment and then TSH every month for the first 3 mo, then every 2–3 mo |

| 131I-based cancer therapies | Tositumomab with 131I: CD-20 antibody with 131I allowing targeted delivery of 131I to lymphocytes | Tositumomab with 131I: NHL | Uptake of 131I into thyrocytes with destruction from β-radiation. | Hypothyroidism | 1–6 y | 10%–60% | TSH before treatment. Pretreatment iodine administration to saturate thyroid, usually SSKI four drops three times daily starting 24 h before treatment and continued for 2 wk after treatment dose. TSH every 6 mo for life. |

| 131I iobenguane: MIBG with 131I, allowing targeted delivery to adrenergic tissues | 131I MIBG: Pheochromocytoma, carcinoid, neuroblastoma (none FDA-approved). | ||||||

| Immuno-therapies | Increased expression of MHC-I and tumor-specific antigens leading to NK cell/macrophage/T-cell killing of the cell. | Hepatitis C, hepatitis B, hairy cell leukemia, CML, malignant melanoma, follicular lymphoma, condyloma accuminata, Kaposi sarcoma | Stimulation of autoimmunity | Hashimoto thyroiditis with hypothyroidism, typically not painful | 1–6 mo | 5%–50% | TSH and anti-TPO antibodies before treatment, monitor TSH every 2–3 mo if anti-TPO positive, otherwise every 6 mo. |

| Aldesleukin (IL-2): Activation of NK and T-cells. | Malignant melanoma, renal cell cancer | TSH before treatment and then every 2–3 mo | |||||

| Thalidomide/lenalidomide: Immunomodulators with additional anti-angiogenic and pro-apoptotic activity. | Multiple myeloma, erythema nodosum leprosum, 5q- MDS (lenalidomide) | TSH before treatment, then every 2–3 mo | |||||

| Secondary or central hypothyroidism | |||||||

| Bexarotene | Retinoid X receptor agonist | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | Decreased TSHB gene expression, reduced secretion of TSH | Central hypothyroidism | Hours-days | >90% | TSH and free T4 before treatment. Start LT4 1.6 μg/kg daily on initiation of therapy. Monitor free T4 weekly for 5–7 wk and then every 1–2 mo and adjust LT4 dose as needed. In patients on pretreatment LT4 expect increase in required dose. Stop LT4 or reduce to pretreatment dose when stopping bexarotene. |

| Ipilimumab, tremelimumab | Monoclonal antibody directed against CTLA-4 | Ipilimumab approved for unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Investigational in renal, prostate and bladder cancer, and NHL. | Immune dysregulation with hypophysitis | Central hypothyroidism | 9–24 wk | 5%–17% | Baseline pituitary MRI before treatment. TSH, free T4, and 8 AM cortisol before treatment and then every 2–3 mo. Low threshold for pituitary imaging and complete hormonal evaluation (see text). |

| Thyrotoxicosis | |||||||

| Ipilimumab, tremelimumab | Monoclonal antibody directed against CTLA-4 | Ipilimumab approved for unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Investigational in renal, prostate and bladder cancer, and NHL. | Immune dysregulation | Painful thyroiditis, Graves disease | 1–3 mo | Rare | Baseline pituitary MRI before treatment. TSH, free T4, and 8 AM cortisol before treatment and then every 2–3 mo. Low threshold for pituitary imaging and complete hormonal evaluation (see text). |

| Alemtuzumab | Anti-CD52 antibody | B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, investigational for conditioning before stem cell transplant, and for GVHD | Immune reconstitution abnormalities | Graves disease | 6–31 mo | 10%–30% (in patients with multiple sclerosis) | TSH before treatment, then every 2–3 mo |

| Interferon-α | Increased expression of MHC-I and tumor-specific antigens leading to NK cell/macrophage/T-cell killing of the cell. | Hepatitis C, hepatitis B, hairy cell leukemia, CML, malignant melanoma, follicular lymphoma, condyloma accuminata, Kaposi sarcoma | Immune dysregulation | Graves disease or painful thyroiditis | 4–9 mo | 1% | TSH and anti-TPO antibodies before treatment, monitor TSH every 2–3 mo if anti-TPO positive, otherwise every 6 mo. |

CD = Cluster of differentiation; CML = chronic myeloid leukemia; CTLA-4= cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; GIST = gastrointestinal stromal tumors; GVHD = graft-vs-host disease; IL-2 = interleukin 2. LT4 = levothyroxine; MDS = myelodysplastic syndrome; MHC = major histocompatibility complex; MIBG = metaiodobenzylguanidine. MRI = Magnetic resonance imaging; NHL= non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NK = natural killer; SSKI = saturated solution of potassium iodide; T4 = thyroxine; TKIs = tyrosine kinase inhibitors; TPO = thyroid peroxidase; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone; TSHB = Gene encoding the β-subunit of thyroid-stimulating hormone.

It is useful to distinguish between the two commonest causes of thyrotoxicosis (symptoms attributable to excess thyroid hormone). The first is hyperthyroidism (thyroid hormone overproduction) such as occurs in Graves disease; the second is release of preformed thyroid hormone because of inflammation (thyroiditis). This may be caused by release of cytokines, viral infection, or probably hypoxia attributable to the adverse effect of certain drugs such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) on the thyroidal microvasculature. The hyperthyroid phase of the thyroiditis seen with TKIs tends to be mild but eventually leads to hypothyroidism. Thyrotoxicosis due to acute cytokine release may be more severe but can result in either transient or permanent hypothyroidism.

Normal Thyroid Function

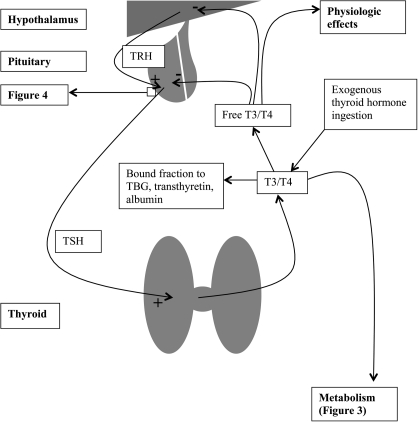

In the normal hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis (40), thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) is secreted by the hypothalamus into the hypophyseal portal vein, which carries it to the anterior pituitary. The anterior pituitary releases thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in response to TRH. TSH acts on the thyroid to stimulate all steps involved in thyroid hormone biosynthesis and secretion. Thyroxine (T4) is secreted together with triiodothyronine (T3) from the thyroid. Some T4 is bound to thyroxine-binding globulin, transthyretin, and albumin, whereas the remainder is free and exerts physiological effects. In treated hypothyroid patients, thyroid hormone is ingested as levothyroxine. Exogenous or endogenous T4 is monodeiodinated to the active form of the hormone, T3, by types 1 or 2 deiodinase present in peripheral tissues. Both T4 and T3 exert negative feedback on TRH secretion from the hypothalamus and on TSH secretion from the pituitary (Figure 1) (40).

Figure 1.

Normal thyroid hormone physiology. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) is secreted by the hypothalamus into the hypophyseal portal vein, which carries it to the anterior pituitary. The anterior pituitary releases thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in response to TRH. TSH acts on the thyroid to stimulate all steps involved in thyroid hormone biosynthesis and secretion. Thyroxine (T4) is secreted together with triiodothyronine (T3) from the thyroid. Some is bound to thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG), transthyretin, and albumin, whereas the remainder is free and exerts physiological effects. In hypothyroid patients, thyroid hormone is ingested as levothyroxine. Exogenous or endogenous T4 is monodeiodinated to the active form of the hormone, T3, by types 1 or 2 deiodinase present in peripheral tissues. Both T4 and T3 exert negative feedback on TRH secretion from the hypothalamus and on TSH secretion from the pituitary.

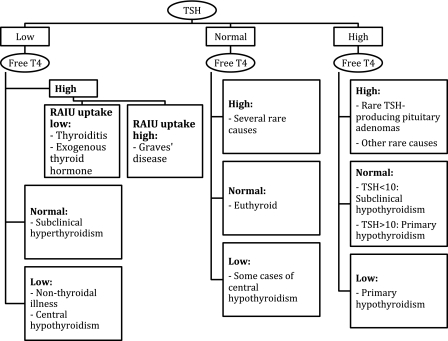

The single best screening test for thyroid dysfunction is a TSH assay, except in patients with pituitary disease (Figure 2). In these patients, as well as in all patients with an abnormal TSH, assessment of free thyroxine is indicated. Serum triiodothyronine determinations are rarely helpful because serum T3 levels are usually suppressed in sick patients (41).

Figure 2.

Interpretation of common tests of thyroid function. There are other possible rare causes of elevated free thyroxine (T4) with normal or elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). These include thyroid hormone resistance; treatment with amiodarone or high-dose propranolol (which reduces conversion of T4 to triiodothyronine [T3]); amphetamine-induced hyperthyroxinemia; or some patients on antipsychotic medications. TSH provides the single best assessment of thyroid status. If it is abnormal, or if a pituitary etiology of thyroid dysfunction is suspected, the measurement of a free T4 is the next step. Note that an estimation of free thyroxine should be done, rather than simply a total T4. This can be done by a direct measurement of free T4 or the total T4 combined with an indirect determination of the fraction of free thyroid hormone (usually a determination of T3 resin uptake, or thyroid hormone–binding ratio). A radioactive iodine uptake (RAIU) is helpful to determine the etiology of thyrotoxicosis, with a value above 25% being consistent with hyperthyroidism (usually Graves disease), vs a destructive thyroiditis in which the uptake is very low. A thyroid scan is usually not necessary for making this distinction.

Radioactive iodine uptake, in which a test dose of 123I is given orally and its uptake into the thyroid gland is measured 6 or 24 hours later, is useful to distinguish Graves disease from other etiologies of thyrotoxicosis such as thyroiditis (42). Thyroiditis is inflammation of the thyroid, which can be autoimmune (Hashimoto thyroiditis), post-viral, related to therapeutic drugs, or from other thyroid insults. Hashimoto thyroiditis typically leads to hypothyroidism, but in some patients, the process may be so severe and acute that the release of preformed thyroid hormone is sufficient to cause thyrotoxicosis. A thyroid gland affected by thyroiditis has a low uptake of radioactive iodine, whereas a patient with Graves disease typically has a 24-hour iodine uptake above 25% (42). Because of the frequent use of computed tomography scans with iodinated contrast in cancer patients, it may be difficult to use 123I uptake to distinguish between thyrotoxicosis from increased thyroid hormone synthesis vs that attributable to thyroiditis. The uptake will be low in both cases if the gland is already saturated with nonradioactive iodine from iodinated contrast (42). In primary hypothyroidism, thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies can be used to distinguish autoimmune disease from other etiologies of hypothyroidism (43). These are also frequently present in patients with Graves disease (43).

Antineoplastic Agents and Their Association with Thyroid Disease

Targeted Therapies

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) are small molecules, usually analogs of ATP, that prevent ATP from binding to critical sites of a wide variety of tyrosine kinases that are involved in the phosphorylation of cellular signaling proteins essential for tumor cell survival and proliferation (44). These include breakpoint cluster region proto-oncogene ABL1 (BCR-ABL) fusion protein; epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR); vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) 1, 2, and 3; platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-α; mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ERK; and v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF). The available agents have varying affinities for the different tyrosine kinases, but none is specific for a single tyrosine kinase, and they may also affect other off-target intracellular processes (44).

Two types of thyroid disturbance can be seen with TKIs. The first is a recurrence of hypothyroidism in patients with preexisting hypothyroidism under satisfactory treatment with thyroid hormone. This effect is seen with imatinib, sorafenib, and motesanib but has not yet been reported with sunitinib (45–49). A prospective study (45) investigating the use of imatinib for the treatment of metastatic medullary thyroid cancer showed that all eight patients on previously stable doses of levothyroxine hormone replacement after thyroidectomy developed grossly increased levels of TSH (average TSH level increased from 1.32 to 23.83 mIU/L) and reduced serum free T4 levels (average free T4 level decreased from 1.45 to 1.09 ng/dL) within 2 weeks of starting this agent. Despite doubling the dose of levothyroxine, the TSH only normalized in three patients. TSH levels returned to normal after discontinuing imatinib (45). Similar effects have been seen in thyroidectomized thyroid cancer patients with other TKIs, such as sorafenib and motesanib (46–49). For imatinib, this effect on thyroid function appears to be limited to patients with hypothyroidism who are taking exogenous thyroid hormone replacement because studies in patients with normal pretreatment thyroid function showed no change in hormone levels (50). The TSH elevation is likely attributable to the accelerated clearance of thyroid hormone through its inactivating pathways, primarily increased activity of type 3 deiodinase, which inactivates both T3 and T4 (46) (Figure 3). In a thyroidectomized patient who cannot increase thyroid hormone production, increased type 3 deiodinase activity would reduce availability of thyroid hormone.

Figure 3.

Thyroid hormone metabolism. Thyroid hormone is inactivated primarily by type 3 deiodinase (D3), which removes one iodine from the 3 or 5 position of triiodothyronine (T3) or thyroxine (T4), forming compounds that will not bind to the thyroid hormone receptor. About 20% of T4 is conjugated to sulfate or glucuronide and cleared by biliary excretion. D1, D2 = Type 1 and type 2 deiodinase, respectively; rT3 = Reverse triiodothyronine; T2 = 3, 3′ diiodothyronine.

In patients initiating imatinib, sorafenib, or motesanib therapy, who are receiving exogenous levothyroxine, we recommend a pretreatment TSH followed by monitoring of TSH every 4 weeks and appropriate adjustment of the levothyroxine dose. Once the TSH and dose of levothyroxine are stable, the frequency of monitoring can be decreased to every 2 months. For imatinib, it is worth considering empirically doubling the dose of levothyroxine on initiation of therapy.

The second type of thyroid disturbance seen with TKIs is hypothyroidism in patients with previously normal thyroid function. In a prospective study (51) of thyroid function in patients receiving sunitinib for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (51), 42 patients without preexisting hypothyroidism were followed prospectively. Fifteen (32%) developed hypothyroidism (TSH greater than 10), with nine having a TSH greater than 20 mIU/L. This high incidence has been replicated in other studies including populations receiving sunitinib for other malignancies, with a range of 32%–85% (25,44,52–55). The onset of hypothyroidism is variable, ranging from 4 to 94 weeks after initiation of treatment (51,52). Although the majority of patients have permanent hypothyroidism (51), reversibility is suggested by an increase in TSH during sunitinib administration that recovers during the 2-week interval off treatment (56).

Sorafenib has also been associated with hypothyroidism in patients with previously normal thyroid function, with an incidence of 18% in one study (57,58) and 67% in another study (58). Other TKIs have also been associated with thyroid disease in patients with previously intact thyroid function. In a retrospective study of 64 patients treated for chronic myeloid leukemia, hypothyroidism was seen in 13%, 50%, and 22% of patients treated with imatinib, dasatinib, or nilotinib, respectively (59). The incidence of preceding transient thyrotoxicosis was also high, suggesting a phase of thyroiditis preceding the loss of function (59). Axitinib, an investigational TKI, was associated with the development of a reversibly increased TSH in nine of 12 Japanese patients, with onset within 1 month of starting treatment (60). Hypothyroidism was also reported with cediranib, another VEGFR blocker being investigated in solid tumors, with an incidence of 45% in one study (61). There are currently no reports of thyroid dysfunction with erlotinib or gefitinib.

The mechanism of TKI-induced hypothyroidism is unclear. Case reports of thyrotoxicosis preceding the development of hypothyroidism suggest that there is a preceding thyroiditis (51,54,58–60,62–65). Some suggestions for the mechanism of hypothyroidism seen with TKIs include direct toxic effects on thyrocytes, reduced TPO activity (53), impaired iodine uptake (56), or stimulation of Hashimoto thyroiditis (66), although Hashimoto thyroiditis is unlikely to be the main mechanism because of the low prevalence of anti-TPO antibodies in patients with sunitinib-induced hypothyroidism (55,56). The most likely explanation is that the thyroid dysfunction is related to the effects of these agents on tyrosine kinases involved in vascular function, such as VEGFR. This could cause attenuation of the thyroid blood flow to this extremely vascular gland. If the blood flow decreases rapidly, an ischemic thyroiditis could result, leading to a transient period of thyrotoxicosis. If the decreased blood flow develops more slowly, gradual thyroid destruction may occur with resulting hypothyroidism (57). Supporting evidence for this theory includes the finding that thyroid cells express VEGF and VEGFR mRNA, and mouse studies have shown glandular capillary regression with TKI exposure (67). In humans, two recent case reports demonstrated reduced thyroid volume and reduced vascularity by Doppler ultrasound (56,68,69), with rapid increase in the size of the thyroid with cessation of sunitinib. This reduced thyroid volume (because of reduced blood flow) may also explain the impaired radioactive iodine uptake in vivo (56) but not in vitro (70). It should be noted that bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against VEGF-A, has not been consistently associated with thyroid disease. One study (71) found hypothyroidism in seven of 30 children treated with bevacizumab for primary central nervous system tumors, but these children had received radiation therapy to the brain, which can itself be associated with hypothyroidism (71).

For patients treated with TKIs who are not receiving thyroid hormone replacement, systematic monitoring of thyroid function is required. Wolter et al. (52) recommended measuring TSH and T4 before treatment with sunitinib and then monitoring TSH on days 1 and 28 of the first four cycles, then on day 28 of every third cycle (52). Torino et al. (72) recommended measurement of thyroid function tests before treatment with TKIs and then measuring TSH on day 1 of every cycle (72). These screening regimens are complex and may be difficult to implement. We therefore suggest measurement of TSH before treatment, then every 4 weeks for 4 months, then every 2–3 months.

Bexarotene.

Bexarotene is a selective agonist of the retinoid X receptor (RXR), a nuclear hormone receptor that has several functions. Most pertinent is its ability to form heterodimers with other nuclear transcription factors, such as the thyroid hormone receptor, retinoid A receptor, vitamin D receptor, and peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (73,74). Activation of RXR causes alteration of cell growth, apoptosis, and cell differentiation. Bexarotene is currently approved for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (75) and is also under investigation for psoriasis and other cancers, such as lung, breast, and thyroid cancer (76).

Systemic administration of bexarotene is associated with central hypothyroidism (77). In one study (77), 26 of 27 patients given bexarotene for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma developed a low T4 with reduced or low–normal TSH. This combination is the classical pattern of central hypothyroidism (Figure 2). The fall in TSH was rapid after starting therapy and reversible within a few days of discontinuing the medication. In other phase II/III studies, 40%–100% of participants receiving bexarotene developed reversible central hypothyroidism (77,78), with TSH suppression occurring within 4–8 hours (79). Indeed, in rats, the fall in TSH was noted as soon as 30–60 minutes after administration (80).

Bexarotene appears to interfere with the normal feedback of thyroid hormone on the pituitary (77,81). T3 binding to its receptor in the pituitary leads to heterodimerization of the receptor with RXR, which suppresses transcription of the β-subunit of TSH, which is required for thyroid stimulation (Figure 4). In the presence of bexarotene, the inhibition of transcription becomes ligand (T3) independent (77,81). In addition to reducing TSH-β mRNA levels, bexarotene also directly inhibits secretion of TSH from the thyrotrophs (80). This inhibition of secretion explains the immediate fall in TSH levels after exposure to bexarotene.

Figure 4.

Intracellular action of thyroid hormone. Thyroid hormone acts mainly via nuclear receptors. Thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) enter the cells, and T4 can be converted to its active form, T3, by intracellular type 2 deiodinases. T3 will bind to the thyroid hormone receptor (TR), which associates with the retinoid X receptor (RXR). The complex binds to the thyroid response element (TRE), which interacts with DNA and increases or decreases mRNA transcription. This leads to altered protein expression, which leads to most of the physiological effects of thyroid hormone. In addition, this will reduce thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) production.

Bexarotene also has TSH-independent effects on thyroid hormone metabolism. Thyroidectomized thyroid cancer patients receiving thyroid hormone replacement who started bexarotene had a dramatic decrease in T3, T4, and free T4 levels with TSH levels that failed to rise appropriately (82), probably because of an effect on peripheral thyroid hormone metabolism via non-deiodinase mechanisms. Indeed, one study found an increase in T4-sulfate (82) (Figure 3), and other studies found induction of liver cytochrome P450 systems that also metabolize thyroid hormone (83). These effects suggest an increased requirement for levothyroxine to achieve appropriate therapeutic levels.

Specific recommendations have been formulated for the management of hypothyroidism during bexarotene therapy (84,85). Sherman (85) recommended starting 50 μg of levothyroxine simultaneously with bexarotene and then measuring free T4 level weekly for the first 5–7 weeks, then every 1–2 months, and allowing adjustment of the dose of levothyroxine to maintain the free T4 within the normal range. Because bexarotene directly affects TSH secretion, bexarotene-treated patients should be monitored with free T4 rather than TSH levels. Because thyroid hormone degradation is affected, clinicians should anticipate the need for higher than usual thyroid hormone replacement dosages in these patients (often two to three times the typical replacement dosage of 1.6 μg/kg ideal body weight per day) (84,85). We therefore recommend starting levothyroxine at 1.6 μg/kg body weight per day (rather than 50 μg) to maintain normal thyroid hormone levels.

Iodine-Based Cancer Therapies—Radioimmunotherapy.

Several antineoplastic agents act by combining Iodine-131 (131I), which kills cells by the release of cytotoxic β-radiation during isotopic decay, with a moiety conferring targeted delivery of the radioiodine to malignant cells. However, thyroid cells will concentrate the 131I released from these agents, leading to hypothyroidism in a substantial proportion of patients. Tositumomab is a Cluster of Differentiation 20 (CD20) antibody combined with 131I, which is approved for treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The incidence of treatment-related hypothyroidism is 9%–41% (86–88), usually as a late side effect (6–24 months or longer) after treatment. A similar prevalence has been seen in studies of the non–FDA-approved combination of rituximab, another CD20 antibody, with 131I (89,90). Likewise, 131I iobenguane (or 131I metaiodobenzylguanidine) has been used to target 131I uptake into neuroendocrine tissues, with investigational uses including pheochromocytoma, carcinoid, and neuroblastoma. Rates of hypothyroidism have been reported to range from 12% to 64% (91–93). Prevention of hypothyroidism, usually by administering oral iodine in the form of Lugol solution or saturated solution of potassium iodide (SSKI), is routinely implemented before and during administration of these medications. However, SSKI itself can cause hypothyroidism or thyrotoxicosis (94). SSKI is usually given at a dose of four drops three times daily, starting 24 hours before administration of the medication and continuing for 2 weeks after. Because Lugol iodine has only about one-sixth the amount of iodine as SSKI, it needs to be given at a higher dose (24 drops three times daily). TSH should be measured before treatment and then monitored semiannually to diagnose late-onset hypothyroidism.

Denileukin Diftitox.

Denileukin diftitox is a drug in which the ligand-binding domain of IL-2 is fused to diphtheria toxin (95). The IL-2 domain binds to the IL-2 receptors on lymphocytes and macrophages, and the toxin moiety inhibits protein synthesis leading to cell death. It is approved for use in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and has also been investigated for use in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and to treat graft-vs-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplant (95). Thyrotoxicosis was seen in one patient in a phase III trial of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (96). Afterward, eight patients with positive TPO antibodies who developed thyrotoxicosis within 1–35 days of treatment with denileukin diftitox were reported in a retrospective case series (97).

The mechanism of denileukin-induced thyroid dysfunction is unclear. Although administration of IL-2 itself is associated with thyroid disease, the IL-2 component of denileukin diftitox does not activate the IL-2 receptor and should therefore not be associated with lymphocyte activation. In addition, the drug should not be toxic to thyrocytes because they do not have high-affinity IL-2 receptors (97). The thyrotoxicosis is likely from thyroiditis because radioactive iodine uptake was reduced, and five of the eight patients eventually developed permanent hypothyroidism (97). The authors (97) suggest that the thyroiditis may be triggered in susceptible individuals by the effect of cytokines released into the general circulation as tumor cells lyse. Alternatively, these anti-TPO antibody–positive patients likely have an increased number of T-lymphocytes present in the thyroid gland. In the presence of denileukin diftitox, these intrathyroidal lymphocytes may lyse and release cytokines locally, leading to thyroiditis (97). We recommend measurement of TSH and anti-TPO antibodies before treatment and then TSH measurements every month for the first 3 months, then every 2–3 months thereafter for patients receiving this therapy.

Alemtuzumab.

Alemtuzumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to the CD52 receptor on lymphocytes and monocytes causing complement-mediated lysis of these cells and profound lymphopenia (98). It is FDA-approved for hematological malignancies, mainly high-risk or previously treated B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (99). Alemtuzumab is also used for conditioning for stem cell transplants and for graft-vs-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplant and is being investigated for autoimmune disorders including multiple sclerosis (100–102). Nine of 27 participants receiving this drug for multiple sclerosis developed TSH receptor antibody–positive Graves disease 9–31 months after treatment, and two others developed thyroiditis (103). Another study of alemtuzumab in patients with multiple sclerosis reported hyperthyroidism in 14.8%, hypothyroidism in 6.9%, and thyroiditis in 4.2% (100). Thyroid disease has also been described in patients receiving alemtuzumab for vasculitis, Behçet disease, and renal transplant immunosuppression (98,104,105).

The mechanism of thyroid autoimmunity after alemtuzumab treatment is likely related to loss of self-tolerance in the immune reconstitution that occurs following profound lymphopenia, analogous to what occurs after initiation of antiretroviral therapy for infection with the HIV, and during immune system recovery after bone marrow transplantation (106). With alemtuzumab, the autoimmune effects are mostly antibody mediated (type 2 hypersensitivity), including Graves disease, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, Goodpasture syndrome, and autoimmune neutropenia (100,107). It is unknown why antibody-mediated autoimmunity is favored and why thyroid dysfunction has not been described in oncology patients. The lack of thyroid dysfunction in cancer patients when compared with patients with multiple sclerosis may be related to the concurrent use of other immunosuppressive agents in cancer patients or to the underlying autoimmunity in patients with multiple sclerosis. In the absence of evidence of thyroid dysfunction with alemtuzumab in cancer patients, we extrapolate findings from patients with multiple sclerosis and recommend measuring TSH before starting treatment and then every 2–3 months during alemtuzumab therapy.

Immunotherapies

Interferon-α.

Interferon-α is a cytokine that increases the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and tumor-specific antigens on the tumor cell surface, stimulating immune-mediated destruction of the cell (108). It also has direct antitumor effects. Interferon-α is used in hepatitis C, melanoma, renal cell cancer, and some hematologic malignancies (108) and has been associated with several types of thyroid disease, all of which appear to be more common in patients receiving the drug for hepatitis C than for malignant indications (109). It has been suggested that the hepatitis C virus itself is associated with thyroid dysfunction (109). The most common thyroid abnormality seen with interferon-α is a destructive or autoimmune thyroiditis, leading to hypothyroidism after a brief thyrotoxic phase. Interferon-α has also been associated with Graves disease (110). The risk of hypothyroidism has been reported to be 2%–10% (110–115), with a risk of thyroid autoimmunity (including development of thyroid autoantibodies) approaching 20% (116,117). The presence of anti-TPO antibodies before treatment increases the risk of hypothyroidism fourfold (118–120). The onset is 1–23 months after initiation of treatment, with a median of 4 months (110,114). The hypothyroidism is persistent in almost 60% of patients (113,121), although transient hypothyroidism has also been described (122). Graves disease after interferon-α treatment does not generally remit on withdrawal of the drug (115).

Interferon-α may likely result in thyroid disease by stimulating an autoimmune response. Interferon-α increases MHC class I expression on thyroid tissue from Graves patients but only if lymphocytes are present in the thyroid tissue (123). Furthermore, overexpression of these antigens has been associated with activation of cytotoxic T-cells with resulting cellular destruction (124). Hence, interferon-α can aggravate an immune response in subjects who have preexisting subclinical thyroiditis with intrathyroidal lymphocytes (123). In addition, interferon-α can shift the immune response to a Th1-mediated immune response, which is associated with increased production of the proinflammatory cytokines interferon-γ and IL-2, which then can trigger an autoimmune response. Direct effects on thyroid cells, leading to nonautoimmune destructive thyroiditis, have also been described (109,115,120,125).

No specific recommendations exist for patients treated with interferon-α for oncological indications, although recommendations have been made for patients with hepatitis C (126). We recommend the same screening in oncological patients, with pretreatment TSH and anti-TPO antibodies, followed by a TSH measurement every 2 months if the patient is TPO antibody positive. In TPO antibody–negative patients, a semiannual TSH is sufficient.

Aldesleukin (IL-2).

IL-2, a cytokine that activates natural killer cells and antigen-specific T-cells, is used pharmacologically to stimulate tumor cell killing, sometimes in conjunction with lymphokine-activated killer cells. It is approved for use in melanoma and renal cell cancer, although its use has declined as better-tolerated and more effective agents have become available.

Many reports (127,128) describe an increase in the incidence of autoimmune disease after IL-2 therapy, although some patients received lymphokine-activated killer cells or interferon-α concurrently. Thyroid disease is particularly common with an incidence of 10%–50%, but a range of other autoimmune toxic effects has been described (28,29,127–131). In addition to hypothyroidism, biphasic thyroiditis and thyrotoxicosis have also been described (129,132–134). Hypothyroidism usually occurs 4–17 weeks after initiation of treatment (28,29). It may be reversible on discontinuing the drug (29,132).

IL-2 therapy is believed to cause thyroid disease by stimulating autoreactive lymphocytes, leading to autoimmune thyroiditis. Human studies have shown that patients treated with IL-2 have higher rates of thyroid autoantibody positivity (28,130) and increased lymphocyte infiltration of the thyroid gland (135). Patients with thyroid disease who underwent fine needle aspiration had features consistent with autoimmune thyroiditis (134). Patients with preexisting positive autoantibodies appear to have a higher risk of developing hypothyroidism during IL-2 treatment (29). Patients treated with IL-2 also have increased levels of interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α, which may enhance presentation of human leukocyte antigen class II and associated autoantigens by thyrocytes leading to autoimmunity, or IL-2 may have direct effects on thyrocyte functioning (136–138). We recommend measuring TSH before treatment and then every 2–3 months during treatment with IL-2.

Ipilimumab/Tremelimumab.

Ipilimumab and tremelimumab are monoclonal antibodies directed against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, a receptor expressed on T-cells that exerts a suppressive effect on the immune response after T-cell/antigen-presenting cell interaction (139). Blocking the receptor leads to increased T-cell activation and antitumor effects. Ipilimumab is approved for treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma (140). In addition, ipilimumab is being investigated in other solid and hematologic cancers, and tremelimumab is being investigated for prostate cancer (141–143).

Ipilimumab and tremelimumab have been associated with immune-related adverse events, most frequently enterocolitis but also hepatitis, cutaneous reactions, uveitis, pancreatitis, arthritis, nephritis, and lymphocytic hypophysitis (autoimmune destruction of the pituitary gland, leading to impaired anterior and sometimes posterior pituitary function) (144–146). In the initial phase I study of tremelimumab, one patient developed hypophysitis (139). In the studies of ipilimumab, eight patients (5% of the participants in the study) developed hypophysitis, with onset 9–24 weeks after initiation of treatment (147). Incidence in other studies ranged from 0% to 17% (148,149). Most patients presented with vague symptoms of fatigue, headache, memory difficulties, and constipation. All eight patients in the initial study had adrenal and thyroid insufficiency from pituitary failure, and most also had hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. These broad effects are different from those associated with bexarotene, which causes selective loss of TSH. Treatment of hypophysitis includes lifelong hormone replacement therapy because only a few patients recover pituitary function (30,150). Ipilimumab is usually stopped if hypophysitis develops, although some patients have been rechallenged with ipilimumab with no adverse events (151). In addition, treatment of hypophysitis with high-dose glucocorticoids has been suggested, although this is not routine and evidence for benefit is lacking (30,147). However, high-dose glucocorticoid treatment does not appear to alter the antineoplastic effects of the drug (147,152). Thyroiditis (139,153,154) and euthyroid Graves ophthalmopathy (153) have also been associated with these agents.

We recommend measuring TSH, free T4, and morning cortisol levels before initiating treatment and then every 2–3 months or sooner if the patient develops symptoms of headache, nausea, vomiting, lethargy, or constipation. If any endocrine dysfunction occurs, we recommend emergent referral to an endocrinologist for further evaluation. The patient may require hospital admission for expedited work-up. A pituitary protocol magnetic resonance imaging scan should be performed to evaluate for hypophysitis. In addition, remaining pituitary function should be assessed (testosterone or estrogen, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, prolactin, adrenocorticotrophic hormone), including an assessment for diabetes insipidus (serum sodium level, monitoring of urine output). No consensus has emerged regarding continuation of the antineoplastic agent or treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids. We suggest stopping the inciting agent. If the agent must be restarted, close monitoring of pituitary function (8 AM cortisol, TSH, and free T4) should be done. If high-dose glucocorticoids are initiated, a suggested regimen is 4 mg of dexamethasone every 6 hours for 7 days, followed by a rapid taper to 0.5 mg daily, and then a change to prednisone or hydrocortisone at replacement doses under the guidance of an endocrinologist.

Immunomodulatory Drugs: Thalidomide/Lenalidomide.

Thali-domide and lenalidomide are immunomodulatory drugs with a range of antineoplastic actions (155,156). They enhance T-cell stimulation and proliferation, induce endogenous cytokine release, and increase the number and function of natural killer cells, thus enhancing immune-mediated destruction of tumor cells. They also have antiangiogenic activity by inhibiting angiogenic growth factors, and they inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis of tumor cells (155,156). Thalidomide and lenalidomide are FDA-approved for treatment of multiple myeloma and, in the case of lenalidomide, for 5q myelodysplastic syndrome but are also under investigation for treatment of solid tumors, including thyroid cancer (157–159) and for a range of autoimmune diseases (160).

Reports of hypothyroidism from thalidomide use appeared as early as the 1960s (161), and several more recent reports have appeared as well, as thalidomide use has increased (160,162–164). In a 2002 study (162), 20% of participants who received thalidomide for multiple myeloma developed a TSH greater than 5 mIU/L, and 7% had a TSH greater than 10 mIU/L (162). Hypothyroidism mostly occurred 1–6 months after initiation of treatment (162).

Lenalidomide shares many of the features of thalidomide, but it is more potent and has fewer side effects (165,166). In larger studies (167,168), the rates of hypothyroidism with lenalidomide have been reported to be 5%–10% (167,168). A recent case series (169) found thyroid abnormalities in 10 of 170 lenalidomide-treated patients after a median of 5 months of therapy. The patients reportedly had both hypothyroidism and thyrotoxicosis, and many had been exposed to prior radiation or thalidomide (169). In two additional case reports of thyroid dysfunction associated with lenalidomide, a period of suppressed TSH was noted. One patient recovered, whereas the other became permanently hypothyroid (170,171).

Many mechanisms have been suggested for the hypothyroidism seen with thalidomide (162). Older studies from the 1950s and 1960s suggested an inhibition of thyroid hormone secretion (172) or a reduction of iodine uptake into follicular cells (173). Because these agents are antiangiogenic, one possibility is that thalidomide and lenalidomide compromise the blood flow to the thyroid in a manner similar to what is suggested for TKIs (162). TSH suppression before the development of hypothyroidism in some patients suggests an ischemic or autoimmune thyroiditis (162). This may be an autoimmune thyroiditis induced by deregulation of cytokine levels or through direct effects on T-lymphocytes (162). A direct toxic effect on thyroid cells is also possible, but this has not been evaluated. We suggest a TSH measurement before treatment and then every 2–3 months during treatment, consistent with recent recommendations (174).

Conclusions and Treatment Recommendations

There are no known strategies to prevent thyroid disease in patients receiving these new antineoplastic agents, and possible preventive measures (such as immunosuppressants to prevent ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis) may be more toxic than the thyroid disease itself. Hence, screening for thyroid disease is likely beneficial, although no official screening recommendations for thyroid function in asymptomatic patients were identified in the literature for patients receiving antineoplastic agents. This is in contrast to amiodarone, a drug with a similar incidence of thyroid side effects (2%–10%) to antineoplastic agents, but where there are official screening recommendations for thyroid function tests every 3–6 months (175,176). We have provided recommendations in this review that are based on prior recommendations where available or based on the specific pattern of thyroid abnormalities anticipated with each agent (Table 1). Although these recommendations are not evidence based, they are logical given the reported complications and provide a framework for providers to identify and treat thyroid dysfunction before the appearance of symptoms. In addition, we recommend monitoring thyroid function tests in all clinical trials of novel antineoplastic agents.

Treatment for thyroid diseases is safe and likely to enhance patient quality of life, as well as potentially allow effective treatments for the underlying cancer to continue. Treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH 5–10 mIU/L with a normal free T4) is generally discouraged in a healthy population because of lack of evidence for benefit (177,178). In the cancer patient, it may be difficult to determine if mild hypothyroidism is truly asymptomatic because of the substantial overlap between symptoms of hypothyroidism with symptoms related to treatment or the underlying disease. Therefore, it seems reasonable to start low-dose levothyroxine therapy in these patients as a therapeutic trial, especially if they are receiving an agent associated with a high risk of hypothyroidism. In patients with TSH greater than 10 mIU/L or with low free T4 levels, treatment should be initiated. In one study (55), at least half of patients who started levothyroxine treatment for sunitinib-associated hypothyroidism had improvement of their symptoms of fatigue (55).

Treatment for hypothyroidism generally consists of thyroid hormone replacement with levothyroxine. A starting dose of 1.6 μg/kg per day is reasonable for patients without underlying cardiac disease. In patients with coronary artery disease, a lower dose such as 50 μg/d may be used for the first few weeks. Monitoring of thyroid hormone replacement is usually by serum TSH measurements, with a goal of maintaining TSH within the normal range. In the case of central hypothyroidism (seen with bexarotene and ipilimumab/tremelimumab), TSH concentrations cannot be used to monitor treatment, and free T4 levels should be monitored, with a goal of about 1–1.5 ng/dL. Although levothyroxine should ideally be taken on an empty stomach at least 1 hour before any other medications to prevent interference with absorption, it is our experience that it simplifies the life of the cancer patient and improves compliance if levothyroxine is taken with other medications. Adjustments in tablet potency can then be made to achieve the desired TSH or free T4 level. Alternatively, there is good evidence to suggest that taking levothyroxine at bedtime leads to increased thyroid hormone levels when compared with morning dosing (179), suggesting that this is an alternative especially if the patients take medications in the morning that would otherwise interfere with thyroid hormone absorption. If the patient is hospitalized and unable to take oral medications, levothyroxine can be held for a few days because it has a long half-life. Alternatively, it can also be given intravenously; the intravenous dose is usually 20%–30% lower than the oral dose to account for the increased bioavailability.

Treatment for thyrotoxicosis is more complex and usually should be done in conjunction with an endocrinologist. Beta-blockers, usually a nonselective agent such as propranolol, can be used for symptom control. Thyrotoxicosis from thyroiditis is usually self-limiting, and specific treatment is not required although such patients must be monitored for subsequent hypothyroidism. For Graves disease, antithyroid medications, such as methimazole (10–30 mg daily), are usually initiated, followed by definitive treatment with 131I ablation, although this cannot usually be done if the patient has received iodinated contrast in the past 3 months.

As this review highlights, there are multiple areas of uncertainty in this topic, and most of the data are derived from case reports or case series, small prospective studies, or laboratory-based studies. There are therefore several paths of research that should be pursued. First, knowledge about the mechanism of thyroid dysfunction may promote further knowledge of the biological effects of the drug, indicate possible preventive strategies, and refine the proposed screening strategies recommended herein. Second, large randomized clinical trials of screening and treatment of thyroid disease should be performed to evaluate improvement in patient quality of life, fatigue, and other symptoms and also to evaluate unanticipated effects on cancer outcomes or other adverse effects. This would only be appropriate in patients who would not otherwise qualify for replacement irrespective of the presence or absence of cancer, such as patients with mild hypothyroidism (TSH less than 10 mIU/L).

In summary, thyroid side effects, mostly hypothyroidism, are common with the newer antineoplastic drugs. These agents affect the thyroid via actions on many levels of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis. Although common, the time of appearance of these off-target effects is not predictable, and we therefore recommend close monitoring of patients receiving these medications. This may allow early recognition and treatment of thyroid disease, allowing continued treatment of the underlying cancer, as well as improving the quality of life of the patient.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (DK36256 and DK44128 to PRL).

Notes

The funders did not have any involvement in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the article; or the decision to submit the article for publication. The authors would like to thank Dr Robert Dluhy and Dr Alfred Lee for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this article. The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.van der Molen AJ, Thomsen HS, Morcos SK. Effect of iodinated contrast media on thyroid function in adults. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(5):902–907. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2238-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markou K, Georgopoulos N, Kyriazopoulou V, Vagenakis AG. Iodine-induced hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2001;11(5):501–510. doi: 10.1089/105072501300176462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger C, Le-Gallo B, Donadieu J, et al. Late thyroid toxicity in 153 long-term survivors of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35(10):991–995. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jereczek-Fossa BA, Alterio D, Jassem J, et al. Radiotherapy-induced thyroid disorders. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30(4):369–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider AB, Sarne DH. Long-term risks for thyroid cancer and other neoplasms after exposure to radiation. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2005;1(2):82–91. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hancock SL, Cox RS, McDougall IR. Thyroid diseases after treatment of Hodgkin’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(9):599–605. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108293250902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beex L, Ross A, Smals A, Kloppenborg P. 5-fluorouracil-induced increase of total serum thyroxine and triiodothyronine. Cancer Treat Rep. 1977;61(7):1291–1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surks MI, Sievert R. Drugs and thyroid function. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(25):1688–1694. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512213332507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong BJ. How medications affect thyroid function. West J Med. 2000;172(2):102–106. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.2.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamby CC, Love RR, Lee KE. Thyroid function test changes with adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(4):854–857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.4.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garnick MB, Larsen PR. Acute deficiency of thyroxine-binding globulin during L-asparaginase therapy. N Engl J Med. 1979;301(5):252–253. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197908023010506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferster A, Glinoer D, Van Vliet G, Otten J. Thyroid function during L-asparaginase therapy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: difference between induction and late intensification. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1992;14(3):192–196. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartalena L, Martino E, Antonelli A, et al. Effect of the antileukemic agent L-asparaginase on thyroxine-binding globulin and albumin synthesis in cultured human hepatoma (HEP G2) cells. Endocrinology. 1986;119(3):1185–1188. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-3-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Djurica SN, Plecas V, Milojevic Z, et al. Direct effects of cytostatic therapy on the functional state of the thyroid gland and TBG in serum of patients. Exp Clin Endocrinol. 1990;96(1):57–63. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1210989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutcliffe SB, Chapman R, Wrigley PF. Cyclical combination chemotherapy and thyroid function in patients with advanced Hodgkin’s disease. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1981;9(5):439–448. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950090505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paulino AC. Hypothyroidism in children with medulloblastoma: a comparison of 3600 and 2340 cGy craniospinal radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53(3):543–547. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02744-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massart C, Le Tellier C, Lucas C, et al. Effects of cisplatin on human thyrocytes in monolayer or follicle culture. J Mol Endocrinol. 1992;8(3):243–248. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0080243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, Jean-Pierre P, Morrow GR. Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist. 2007;12(suppl 1):4–10. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas J. Cancer-related constipation. Curr Oncol Rep. 2007;9(4):278–284. doi: 10.1007/s11912-007-0034-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Connor P, Feely J. Clinical pharmacokinetics and endocrine disorders. Therapeutic implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1987;13(6):345–364. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198713060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen SY, Kao PC, Lin ZZ, Chiang WC, Fang CC. Sunitinib-induced myxedema coma. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(3):370.e1–370.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collinson F, Vasudev N, Berkin L, et al. Sunitinib-induced severe hypothyroidism with cardiac compromise [published online ahead of print November 30, 2010] Med Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9757-z. doi:10.1007/s12032-010-9757-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Lorenzo G, Autorino R, Bruni G, et al. Cardiovascular toxicity following sunitinib therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a multicenter analysis. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(9):1535–1542. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidinger M, Vogl UM, Bojic M, et al. Hypothyroidism in patients with renal cell carcinoma: blessing or curse? Cancer. 2011;117(3):534–544. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolter P, Stefan C, Decallonne B, et al. Evaluation of thyroid dysfunction as a candidate surrogate marker for efficacy of sunitinib in patients (pts) with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15S):5126. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phan GQ, Attia P, Steinberg SM, White DE, Rosenberg SA. Factors associated with response to high-dose interleukin-2 in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(15):3477–3482. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franzke A, Peest D, Probst-Kepper M, et al. Autoimmunity resulting from cytokine treatment predicts long-term survival in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(2):529–533. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.2.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weijl NI, Van der Harst D, Brand A, et al. Hypothyroidism during immunotherapy with interleukin-2 is associated with antithyroid antibodies and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(7):1376–1383. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.7.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atkins MB, Mier JW, Parkinson DR, et al. Hypothyroidism after treatment with interleukin-2 and lymphokine-activated killer cells. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(24):1557–1563. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806163182401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang JC, Hughes M, Kammula U, et al. Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA4 antibody) causes regression of metastatic renal cell cancer associated with enteritis and hypophysitis. J Immunother. 2007;30(8):825–830. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318156e47e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kruit WH, Bolhuis RL, Goey SH, et al. Interleukin-2-induced thyroid dysfunction is correlated with treatment duration but not with tumor response. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(5):921–924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.5.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson M, Hercbergs A, Rybicki L, Strome M. Association between development of hypothyroidism and improved survival in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(10):1041–1046. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.10.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hercbergs AA, Goyal LK, Suh JH, et al. Propylthiouracil-induced chemical hypothyroidism with high-dose tamoxifen prolongs survival in recurrent high grade glioma: a phase I/II study. Anticancer Res. 2003;23(1B):617–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cristofanilli M, Yamamura Y, Kau SW, et al. Thyroid hormone and breast carcinoma. Primary hypothyroidism is associated with a reduced incidence of primary breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103(6):1122–1128. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis FB, Tang HY, Shih A, et al. Acting via a cell surface receptor, thyroid hormone is a growth factor for glioma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(14):7270–7275. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Theodossiou C, Skrepnik N, Robert EG, et al. Propylthiouracil-induced hypothyroidism reduces xenograft tumor growth in athymic nude mice. Cancer. 1999;86(8):1596–1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garfield DH, Wolter P, Schoffski P, Hercbergs A, Davis P. Documentation of thyroid function in clinical studies with sunitinib: why does it matter? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(31):5131–5132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garfield D, Hercbergs A, Davis P. Unanswered questions regarding the management of sunitinib-induced hypothyroidism. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4(12):674. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dentice M, Luongo C, Huang S, et al. Sonic hedgehog-induced type 3 deiodinase blocks thyroid hormone action enhancing proliferation of normal and malignant keratinocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(36):14466–14471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706754104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larsen PR, Davies TF, Schlumberger MJ, Hay ID. Thyroid physiology and diagnostic evaluation of patients with thyroid disorders. In: Kronenberg H, Williams RH, Polonsky KS, et al., editors. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2008. pp. 299–332. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaplan MM, Larsen PR, Crantz FR, et al. Prevalence of abnormal thyroid function test results in patients with acute medical illnesses. Am J Med. 1982;72(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90565-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarkar SD. Benign thyroid disease: what is the role of nuclear medicine? Semin Nucl Med. 2006;36(3):185–193. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sinclair D. Clinical and laboratory aspects of thyroid autoantibodies. Ann Clin Biochem. 2006;43(pt 3):173–183. doi: 10.1258/000456306776865043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lodish MB, Stratakis CA. Endocrine side effects of broad-acting kinase inhibitors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(3):R233–R244. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Groot JW, Zonnenberg BA, Plukker JT, van Der Graaf WT, Links TP. Imatinib induces hypothyroidism in patients receiving levothyroxine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78(4):433–438. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdulrahman RM, Verloop H, Hoftijzer H, et al. Sorafenib-induced hypothyroidism is associated with increased type 3 deiodination. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(8):3758–3762. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gupta-Abramson V, Troxel AB, Nellore A, et al. Phase II trial of sorafenib in advanced thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4714–4719. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schlumberger MJ, Elisei R, Bastholt L, et al. Phase II study of safety and efficacy of motesanib in patients with progressive or symptomatic, advanced or metastatic medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(23):3794–3801. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sherman SI, Wirth LJ, Droz JP, et al. Motesanib diphosphate in progressive differentiated thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(1):31–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa075853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dora JM, Leie MA, Netto B, et al. Lack of imatinib-induced thyroid dysfunction in a cohort of non-thyroidectomized patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158(5):771–772. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Desai J, Yassa L, Marqusee E, et al. Hypothyroidism after sunitinib treatment for patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(9):660–664. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-9-200611070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolter P, Stefan C, Decallonne B, et al. The clinical implications of sunitinib-induced hypothyroidism: a prospective evaluation. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(3):448–454. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong E, Rosen LS, Mulay M, et al. Sunitinib induces hypothyroidism in advanced cancer patients and may inhibit thyroid peroxidase activity. Thyroid. 2007;17(4):351–355. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grossmann M, Premaratne E, Desai J, Davis ID. Thyrotoxicosis during sunitinib treatment for renal cell carcinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;69(4):669–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rini BI, Tamaskar I, Shaheen P, et al. Hypothyroidism in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(1):81–83. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mannavola D, Coco P, Vannucchi G, et al. A novel tyrosine-kinase selective inhibitor, sunitinib, induces transient hypothyroidism by blocking iodine uptake. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(9):3531–3534. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tamaskar I, Bukowski R, Elson P, et al. Thyroid function test abnormalities in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(2):265–268. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miyake H, Kurahashi T, Yamanaka K, et al. Abnormalities of thyroid function in Japanese patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sorafenib: a prospective evaluation. Urol Oncol. 2010;28(5):515–519. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim TD, Schwarz M, Nogai H, et al. Thyroid dysfunction caused by second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors in Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia. Thyroid. 2010;20(11):1209–1214. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mukohara T, Nakajima H, Mukai H, et al. Effect of axitinib (AG-013736) on fatigue, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and biomarkers: a phase I study in Japanese patients. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(4):963–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01465.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goss GD, Arnold A, Shepherd FA, et al. Randomized, double-blind trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel with either daily oral cediranib or placebo in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: NCIC clinical trials group BR24 study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(1):49–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pinar D, Boix E, Meana JA, Herrero J. Sunitinib-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2009;32(11):941–942. doi: 10.1007/BF03345777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Faris JE, Moore AF, Daniels GH. Sunitinib (sutent)-induced thyrotoxicosis due to destructive thyroiditis: a case report. Thyroid. 2007;17(11):1147–1149. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iavarone M, Perrino M, Vigano M, Beck-Peccoz P, Fugazzola L. Sorafenib-induced destructive thyroiditis. Thyroid. 2010;20(9):1043–1044. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barbaro D. Sorafenib and thyrotoxicosis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010;33(6):436. doi: 10.1007/BF03346617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alexandrescu DT, Popoveniuc G, Farzanmehr H, et al. Sunitinib-associated lymphocytic thyroiditis without circulating antithyroid antibodies. Thyroid. 2008;18(7):809–812. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kamba T, Tam BY, Hashizume H, et al. VEGF-dependent plasticity of fenestrated capillaries in the normal adult microvasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290(2):H560–H576. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00133.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Makita N, Miyakawa M, Fujita T, Iiri T. Sunitinib induces hypothyroidism with a markedly reduced vascularity. Thyroid. 2010;20(3):323–326. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rogiers A, Wolter P, Op de Beeck K, et al. Shrinkage of thyroid volume in sunitinib-treated patients with renal-cell carcinoma: a potential marker of irreversible thyroid dysfunction? Thyroid. 2010;20(3):317–322. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Salem AK, Fenton MS, Marion KM, Hershman JM. Effect of sunitinib on growth and function of FRTL-5 thyroid cells. Thyroid. 2008;18(6):631–635. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reismuller B, Azizi AA, Peyrl A, et al. Feasibility and tolerability of bevacizumab in children with primary CNS tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54(5):681–686. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Torino F, Corsello SM, Longo R, Barnabei A, Gasparini G. Hypothyroidism related to tyrosine kinase inhibitors: an emerging toxic effect of targeted therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(4):219–228. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kliewer SA, Umesono K, Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. Retinoid X receptor interacts with nuclear receptors in retinoic acid, thyroid hormone and vitamin D3 signalling. Nature. 1992;355(6359):446–449. doi: 10.1038/355446a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Keller H, Dreyer C, Medin J, et al. Fatty acids and retinoids control lipid metabolism through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-retinoid X receptor heterodimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(6):2160–2164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Duvic M, Hymes K, Heald P, et al. Bexarotene is effective and safe for treatment of refractory advanced-stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: multinational phase II-III trial results. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(9):2456–2471. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haugen BR. Drugs that suppress TSH or cause central hypothyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23(6):793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sherman SI, Gopal J, Haugen BR, et al. Central hypothyroidism associated with retinoid X receptor-selective ligands. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(14):1075–1079. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904083401404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Duvic M, Martin AG, Kim Y, et al. Phase 2 and 3 clinical trial of oral bexarotene (Targretin capsules) for the treatment of refractory or persistent early-stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(5):581–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Golden WM, Weber KB, Hernandez TL, et al. Single-dose rexinoid rapidly and specifically suppresses serum thyrotropin in normal subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(1):124–130. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu S, Ogilvie KM, Klausing K, et al. Mechanism of selective retinoid X receptor agonist-induced hypothyroidism in the rat. Endocrinology. 2002;143(8):2880–2885. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.8.8930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sharma V, Hays WR, Wood WM, et al. Effects of rexinoids on thyrotrope function and the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis. Endocrinology. 2006;147(3):1438–1451. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smit JW, Stokkel MP, Pereira AM, Romijn JA, Visser TJ. Bexarotene-induced hypothyroidism: bexarotene stimulates the peripheral metabolism of thyroid hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(7):2496–2499. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Howell SR, Shirley MA, Ulm EH. Effects of retinoid treatment of rats on hepatic microsomal metabolism and cytochromes P450. Correlation between retinoic acid receptor/retinoid x receptor selectivity and effects on metabolic enzymes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1998;26(3):234–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]