Abstract

Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) is a multifunctional matrix protein that has recently been examined in various wound processes, primarily for its ability to activate the latent complex of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). TGF-β has been shown to play a major role in stimulating mesenchymal cells to synthesize extracellular matrix. After injury, corneal keratocytes become activated and transform into fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Our hypothesis is that TSP-1 regulates the transformation of keratocytes into myofibroblasts (MF) via TGF-β. In the current study, we examined the expression of TSP-1 and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), a marker of MF, during rat corneal wound healing. Three-mm keratectomy or debridement wounds were made in the central rat cornea and allowed to heal from 8 hours to 8 weeks in vivo. Unwounded rat corneas served as controls. Expression of TSP-1, SMA and Ki67, a marker of proliferating cells, were examined by indirect-immunofluorescence microscopy. In unwounded corneas, TSP-1 expression was observed primarily in the endothelium. No expression was seen in the stroma, and only low levels were detected in the epithelium. Ki67 was localized in the epithelial basal cells and no SMA was present in the central cornea of unwounded eyes. After keratectomy wounds, TSP-1 expression was seen 24 hours after wounding in the stroma immediately subjacent to the wound-healing epithelium. The expression of TSP-1 increased daily and peaked 7–8 days after wounding. SMA expression, however, was not observed until 3–4 days after wounding. Interestingly, SMA-positive cells were almost exclusively seen in the stromal zone expressing TSP-1. Peak expression of SMA-positive cells was observed 7–8 days after wounding. Ki67-expressing cells were seen both in the area expressing TSP-1 and the adjacent area. In the debridement wounds, no SMA expressing cells were observed at any time point. TSP-1 was localized in the basement membrane zone from 2–5 days after wounding, and the localization did not appear to penetrate into the stroma. These data are in agreement with our hypothesis that TSP-1 localization in the stromal matrix is involved in the transformation of keratocytes into myofibroblasts.

Keywords: Thrombospondin-1, Myofibroblasts, Provisional matrix, Keratectomy, Corneal wound repair, Corneal stroma

1. Introduction

Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) is a large (450kDa) trimeric, extracellular glycoprotein that is a member of a family of five related proteins (Baenziger et al., 1971; Bornstein, 2001; Carlson et al., 2008; Lawler, 2000; Leung, 1984; Murphy-Ullrich et al., 1993; Murphy-Ullrich and Hook, 1989; Roberts, 2005; Sheibani and Frazier, 1999; Taraboletti et al., 1987). TSP-1 is a major constituent of platelet α-granules (Baenziger et al., 1971; Leung, 1984), and was first purified from human blood platelets in 1978. Its name derives from the observation that platelets exposed to thrombin secrete a “thrombin sensitive protein” (Baenziger et al., 1971; Leung, 1984). TSP-1 is also secreted by a wide variety of epithelial and mesenchymal cells in patterns that suggest that the protein is involved in developmental changes in the embryo and in response to injury in the adult (Baenziger et al., 1971; Bornstein, 2001; Carlson et al., 2008; Lawler, 2000; Leung, 1984; Murphy-Ullrich et al., 1993; Murphy-Ullrich and Hook, 1989; Roberts, 2005; Sheibani and Frazier, 1999; Taraboletti et al., 1987). TSP-1 binds heparin sulfate proteoglycan, several integrins—αVb3, α3β1, α4β1, and α5β1—as well as, CD36, a cell surface receptor. TSP-1 also binds other matrix materials, including plasminogen, fibrinogen, fibronectin, and urokinase. These interactions generate the formation of multi-protein complexes that can pass information between the cell surface and the matrix (Carlson et al., 2008; Lawler, 2000; Roberts, 2005). In addition, TSP-1 also binds the TGF-β latency-associated peptide (LAP), leading to the activation of TGF-β. In this process, the 4 amino acid sequence KRFK in TSP-1 binds to the sequence LSKY in the LAP (Murphy-Ullrich et al., 1993). Interaction between these two sequences leads to a conformational change in the LAP/TGF-β complex that allows TGF-β to interact with its receptors. As would be predicted for a protein that can regulate cell proliferation and migration, TSP-1 is most highly expressed during tissue development and wound repair. TSP-1 is expressed at high levels in developing lung, heart, liver, bone, kidney, cartilage, and skeletal muscle. TSP-1 is also expressed at high levels in healing skin, kidney and lung (Darby et al., 1990; Desmouliere et al., 1993; Friedman, 1993; Murphy-Ullrich et al., 1992). In the skin, TSP-1 is rapidly deposited in the wound site, presumably from degranulating platelets (Agah et al., 2002; Streit et al., 2000). Absence of TSP-1 is associated with delayed healing, prolonged inflammation and delayed scab loss (Agah et al., 2002). Expression of TSP-1 has also been observed to correlate with the level of kidney fibrosis in kidney wound models (Friedman, 1993).

In the adult cornea, TSP-1 has been reported to be localized in the endothelium, Descemet’s membrane (Hiscott et al., 1997; Sekiyama et al., 2006; Uno et al., 2004), and immediately subjacent to the corneal epithelial basal cells (Sekiyama et al., 2006). TSP-1 does not appear to be expressed in the unwounded stroma, but several reports have indicated that it is present after wounding. Uno et al. (2004) reported that TSP-1 was present on the wounded corneal surface within 30 minutes after an abrasion wound in mice. Cao et al. (2002) also demonstrated a 5-fold increase in TSP-1 mRNA 18 hours after an excimer laser wound. In addition, Hiscott et al. (1999) found that TSP-1 was upregulated in human corneas after an incisional wound.

In the current investigation, we examined the relationship between TSP-1 expression and corneal wound repair in two wound models. One in which the basement membrane is left intact and a second where the basement membrane is removed. In the normal cornea, keratocytes, quiescent fibroblasts, are interconnected. Immediately after corneal injury, keratocytes become active and transform into a repair phenotype, termed fibroblasts (Jester et al., 1995; Jester et al., 1987; Weimar, 1957). In some wound types, myofibroblasts differentiate from fibroblasts and are characterized by the presence of stress fibers containing smooth muscle actin (SMA). Myofibroblasts are large contractile cells that are normally associated with scar formation. Previous studies have indicated that TGF-β1 stimulates myofibroblast differentiation (Desmouliere et al., 1993; Friedman, 1993). Thus, we hypothesized that TSP-1 could be involved in the activation of latent TGF-β1, leading to myofibroblast generation (Murphy-Ullrich et al., 1992). We also hypothesized that temporal and spatial differences in TSP-1 expression might explain why wounds without basement membrane damage rarely form myofibroblasts, while wounds involving basement membrane damage frequently express myofibroblasts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Animal Model

All studies conformed to the ARVO Statement for the Use Of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Adult Sprague-Dawley rats were anesthetized and either a 3-mm debridement or keratectomy was made, as previously described (Zieske and Gipson, 1986; Zieske et al., 1987). In brief, the central area of the cornea was demarcated with a 3 mm trephine. For the keratectomy, the trephine was rotated gently to cut into the stroma. The circular area was traced with a sharp pair of surgical forceps, and the anterior portion of the stroma was removed by pulling with the forceps. This type of wound leaves a bare stroma with the epithelium and basement membrane removed. For the debridement, after the area is marked with the trephine, the epithelium within this area is removed by gently scraping with a blade. This type of wound only removes the epithelium and leaves the basement membrane intact. The eyes were allowed to heal for 8 hours to 8 weeks. Six rats for each time point had the right eye wounded, and the contralateral eye served as a control. At the allotted time, animals were euthanized and the eyes were processed for immunofluorescence (Zieske et al., 2001a, 2001b).

2.2 Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Immunofluorescence, using unfixed 6-μm cryostat sections, was performed as previously published (Zieske et al., 2001a, 2001b). In brief, tissue sections were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with anti-thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1: Lab Vision, Thermo Fischer Scientific; Fremont, CA) and/or anti-α-smooth muscle actin (SMA: Dako North America, Inc; Carpinteria, CA), or anti-Ki67 (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA), followed by a 1 hour incubation with the corresponding secondary antibody: fluorescein or rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (TSP-1) or anti-mouse IgG (SMA and Ki67: Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc; West Grove, PA). Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI, a nuclear counter-stain (Vector Laboratories), was used to mount the coverslips. Negative controls, primary antibody omitted, were routinely run with every antibody-binding experiment. Slides were viewed and photographed with a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope equipped with a digital SPOT camera (Micro Video Instruments, Inc; Avon, MA).

3. Results

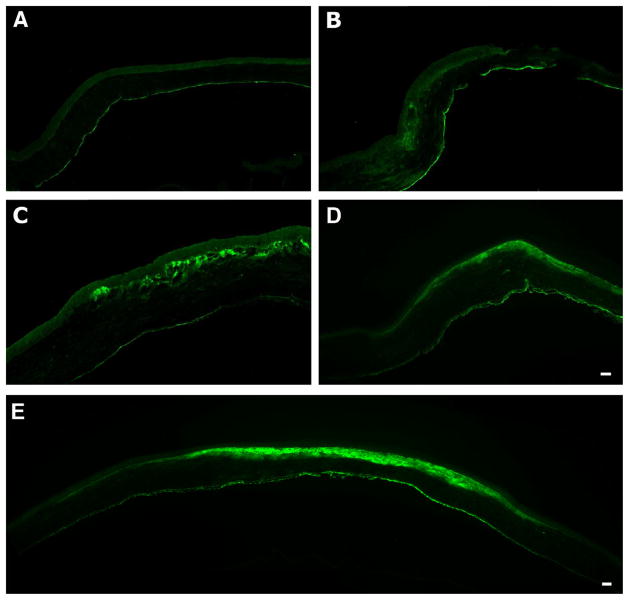

In an initial step to understand the role of TSP-1 during corneal wound healing, 3-mm keratectomies and debridements were performed on adult rats and examined. In unwounded corneas (Fig. 1A), TSP-1 expression was observed primarily in the endothelium. Twenty-four hours after a 3-mm keratectomy, TSP-1 appeared in the stroma at the edge of the wound area just below the leading edge of the epithelium (Fig. 1B). By 48 hours (data not shown), the expression of TSP-1 was localized to the area subjacent to the wound-healing epithelium and increased daily (Fig. 1C and D) and appeared to peak at 7–8 days (Fig. 1E). Some TSP-1 expression was apparent at 2 weeks; however, by 4 weeks post-keratectomy, TSP-1 expression had returned to that seen in unwounded cornea (data not shown). Interestingly, TSP-1 showed a strikingly selective localization in the wound area (Fig. 1E) and never spread into the peripheral stroma outside the original wound area.

Figure 1.

Immunolocalization of TSP-1 after 3-mm keratectomy. As seen in unwounded cornea (A), TSP-1 localized mainly in the endothelium; however, upon wounding (24 hours, B), TSP-1 was present in the stroma just below the leading edge of the wound-healing epithelium. By 3 days (C), TSP-1 localization was present in the stroma subjacent to the wound-healing epithelium and remained in that area, as is seen in (D) 6 days. The maximal TSP-1 localization was seen at 7–8 days (E, 7 days). Of interest, the area in which the TSP-1 localizes does not extend beyond the wound area after the epithelium closes. Bar = 50 microns.

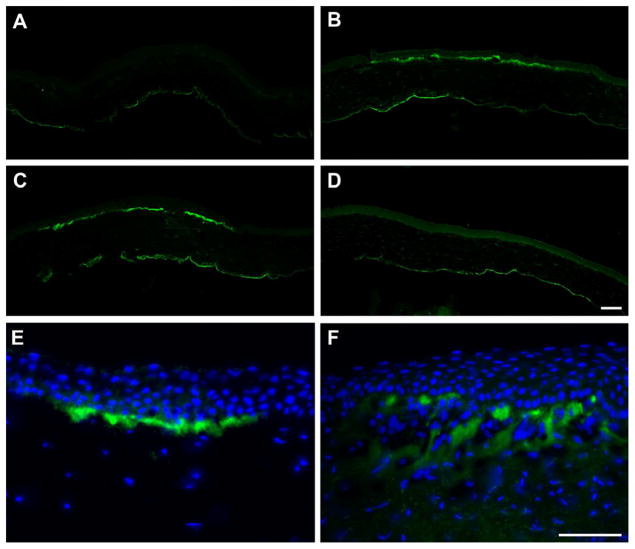

Unlike the keratectomy, TSP-1 expression did not appear in the stroma by 24 hours post-debridement (Fig. 2A). Instead, the expression was slightly delayed and was present by 48 hours (Fig. 2B) and localized subjacent to the wound-healing epithelium. TSP-1 expression also peaked earlier after debridement (Fig. 2C), and no expression was noted by 5 days (Fig. 2D). Note that the expression in the debridement wound, like the keratectomy, remained in the wound area; however, of interest, the depth of the TSP-1 localization in the debridement is much shallower than that in the keratectomy and is confined to the basement membrane zone (Fig 2E and F, respectively). In addition, the localization was not continuous, but appeared in patches.

Figure 2.

Immunolocalization of TSP-1 after 3-mm debridement. Unlike the keratectomy, no TSP-1 localization was present at 24 hours (A) post-debridement. By 48 hours (B), TSP-1 localization appeared just below the wound-healing epithelium in a much narrower margin than the keratectomy. This localization peaked at 3 days (C), and returned to that seen in unwounded cornea by 5 days (D). The difference in the TSP-1 localization between the two wound types was apparent. In the debridement at 3 days (E), the TSP-1 was primarily in the basement membrane zone, whereas, in the keratectomy at 3 days (F), the TSP-1 reaches into the anterior portion of the stroma. TSP-1 = green, DAPI = blue. Bars = 50 microns.

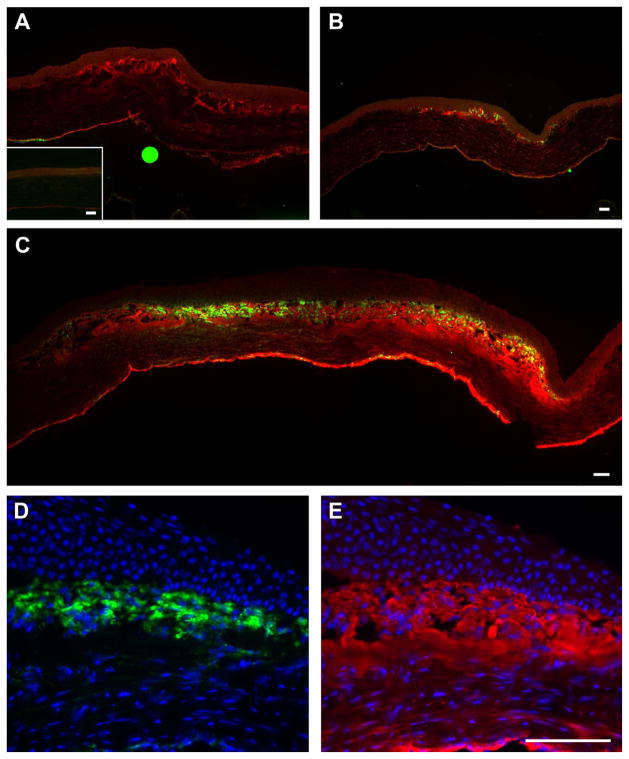

To examine if TSP-1 is associated with the appearance of myofibroblasts, both wound models were stained with anti-SMA. No SMA was present in the debridement tissue (data not shown) or in unwounded control (Fig. 3A, inset) however, by 4 days post-keratectomy, SMA expression is present in the cells subjacent to the wound-healing epithelium (Fig. 3B)—3 days later than TSP-1 (Fig. 3A). As with TSP-1, by 7–8 days post-keratectomy, SMA-positive cells reached their peak (Fig. 3C). Also, like TSP-1, some SMA-positive cells were present at 2 weeks (data not shown). Note that the localization of the SMA-positive cells was in the same area as the TSP-1 (Fig. 3C). Higher magnification of SMA-positive cells in the central portion of the wound area 1 week after keratectomy (Fig. 3D) shows that SMA was indeed in the cells; whereas, TSP-1 is mostly in the matrix of the stroma (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Immunolocalization of SMA and TSP-1 after 3-mm keratectomy. As with TSP-1, there was no SMA present in the unwounded cornea (A, inset) except for in the blood vessels in the limbus (data not shown). After wounding, TSP-1 appeared earlier than SMA and was present in the anterior stroma of the wound area (A, 3 days). By 4 days (B), SMA appeared in the same area as TSP-1, and as with TSP-1, SMA localization peaked by 7–8 days (C, 7 days). Of note, SMA-positive cells were only present in the healing stroma in the area where TSP-1 was present. To confirm localization, higher magnification of 1 week post-keratectomy shows that SMA-positive cells (D) were present only in the area where TSP-1 (E) was localized. SMA = green, TSP-1 = red and DAPI = blue. Bar = 50 microns.

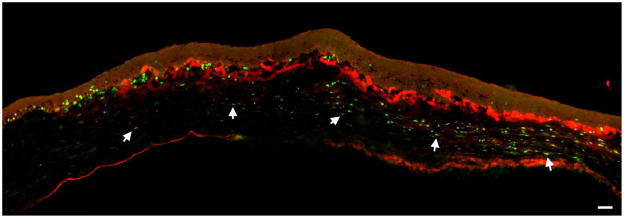

Lastly, we examined Ki67 to determine if there was a relationship between TSP-1 expression and proliferating cells. The proliferating cells in the keratectomy wound were primarily localized subjacent to the original wound area (Fig 4); this is similar to what was seen in debridement wounds (Hutcheon et al., 2005; Zieske et al., 2001a). Interestingly, there was no obvious relationship between Ki67-positive cells and TSP-1 localization. The lack of relationship was seen at all time points (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Immunolocalization of TSP-1 and Ki67 at 3 Days post-keratectomy. Proliferating (Ki67-positive) cells are present in the epithelial basal cells outside of the wound area and in the stroma. Most of the stromal proliferating cells (arrows) are present just below the area in which the TSP-1 is localizing. However, some proliferating cells are present in the TSP-1-positive zone. Ki67 = green, TSP-1 = red. Bar = 50 microns.

4. Discussion

4.1 Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) Expression

One of the major findings of this study is that TSP-1 is deposited in the stroma following a wound where the basement membrane is damaged. Previous investigations have examined TSP-1 localization after a wound where the basement membrane is left intact (Uno et al., 2004). In these investigations and in our current study, TSP-1 was expressed only in the most superficial aspect of the stroma corresponding to the basement membrane zone. Our findings were in basic agreement that TSP-1 expression was maximal early after wounding and rapidly decreased (Uno et al., 2004), some variation in the time course was observed between rats and mice. In a non-ocular model, Bornstein reported that TSP-1 mRNA levels were highest 1 day after wounding and gradually fell to almost undetectable levels by day 10 (Bornstein, 2001).

Following a keratectomy wound, the temporal and spatial localization of TSP-1 varied dramatically compared to the debridement wound. In the keratectomy cornea, TSP-1 expression increased daily and peaked 7–8 days after wounding. Localization decreased after 10 days and returned to control levels in most corneas by 14 days. We also observed major differences in the spatial localization of TSP-1. Perhaps the most important difference was the depth of the TSP-1 localization into the stroma. In the debridement wound, localization was confined to the basement membrane zone. It was not clear from our data, if TSP-1 penetrated beyond the basement membrane; however, following the keratectomy wound, TSP-1 was localized in the anterior one-third to one-half of the stroma. These results suggest that TSP-1 could have differing functions in the two wound models. The localization in the keratectomy model suggests that TSP-1 has the potential to interact with fibroblasts migrating into the wound area, whereas, TSP-1 in the debridement model might play a role in epithelial migration and adhesion. This possibility was suggested by the findings of Uno et al. (2004), who demonstrated that addition of TSP-1 appeared to enhance epithelial migration rates. They did not propose a mechanism of action; however, it is possible that the epithelial cells are adhering to one of the many integrin receptor sites found in TSP-1 (Bornstein, 2001; Bornstein et al., 2004; Carlson et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2000). The enhancement is most likely not the result of TGF-β activation, since TGF-β was shown in numerous studies to block epithelial proliferation and migration. (For Review see Tandon et al. (2010) and Roberts (1998))

In both wound models, TSP-1 expression showed a strikingly selective localization in the wound area subjacent to the wound-healing epithelium. By 7–8 days after a keratectomy, TSP-1 was present in the entire area generated by the original wound. Interestingly, the localization at 7 days appeared extremely compact with little, if any, gradient of TSP-1 extending beyond the original wound area towards the limbus or endothelium (Fig. 1). The selective localization of TSP-1 in the wound area suggests that TSP-1 could potentially play several roles in the keratectomy model, including activator of TGF-β1, transient component of extracellular matrix and participant in adhesion during wound healing.

TSP-1 has been associated with a variety of biological activities, including anti-angiogenesis, cell proliferation, cell migration, and fibrosis (Agah et al., 2002; Bornstein et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2000; Crawford et al., 1998; Kyriakides and Maclauchlan, 2009; Murphy-Ullrich and Poczatek, 2000; Tan and Lawler, 2009). However, in our current study, we found no correlation between TSP-1 expression and stromal cell proliferation. The relationship between TSP-1 expression and fibrosis may be the most relevant to our current investigation. In several systems, the extent of fibrosis appears to correlate with the extent of TSP-1 expression (Chatila et al., 2007; Frangogiannis et al., 2005; Hugo et al., 1998; Xie et al., 2010). In all of these investigations, TSP-1 was detected before myofibroblasts were observed. These authors concluded that TSP-1 promoted fibrosis by activating TGF-β1, which in turn stimulated the formation of myofibroblasts. Indeed when TGF-β1 activation was blocked, fibrosis was blunted. Another interesting aspect of TSP-1 expression is that its localization appears to help form a protective barrier to confine fibrosis to the wound area. This was apparent in both heart and kidney damage (Chatila et al., 2007; Hugo et al., 1998), the fibrosis was confined to the area of TSP-1 expression; however, when TSP-1 expression was blocked, fibrosis was seen in a much wider area (Chatila et al., 2007).

4.2 Colocalization of TSP-1 and myofibroblasts

One of the striking differences between wounds that involve penetration of the basement membrane versus ones that do not is the generation of myofibroblasts. Debridement wounds seldom, if ever, involve the appearance of myofibroblasts and subsequent scarring; whereas, keratectomy-type wounds are associated with myofibroblast formation [for review see - (Saika et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2001)]. Myofibroblast formation has been shown to involve TGF-β1 (Jester et al., 1997; Moller-Pedersen et al., 1998). Since TGF-β1 is normally secreted in an inactive latent form, its activation plays a key regulatory role (Schlotzer-Schrehardt et al., 2001). We hypothesized that one of the functions of TSP-1 in corneal wound repair is the activation of TGF-β1. A comparison of the localization of TSP-1 and SMA suggest that the hypothesis could be correct. As seen in Figures 1 and 3, in the keratectomy wounds, TSP-1 is localized in the wound area beginning at one day; whereas, SMA was not detected until 4 days. In addition, SMA-positive cells were only detected in the TSP-1- positive area of the stroma. These data suggest that as fibroblasts migrate into the wound area, they interact with TSP-1, which activated TGF-β1 in this area. The activated TGF-β1 then stimulates the transformation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. In contrast, in the debridement wound, fibroblasts do not migrate into an area with high levels of TSP-1 and active TGF-β1, and therefore, are not transformed into myofibroblasts. It is not clear from our data if the fibroblasts, myofibroblasts or epithelium produce the TSP-1. However, in culture, both epithelial cells and fibroblasts were stimulated by TGF-β1 to secrete TSP-1 (data not shown). One of the difficulties in studying the effects of TGF-β in wound repair is that TGF-β ββ is secreted in a latent form, and thus, its presence does not necessarily correlate with effect. Most probes of TGF-β ββ do not distinguish between the active and latent forms, and detecting active TGF-ββ β is technically challenging. We are not aware of any studies that have assayed active TGF- ββ β in a corneal wound-healing model. However, most studies agree that TGF-β ββ1 and -ββ β2 are elevated after wounding. We compared the activation of Smad, a TGF-β ββ-signaling molecule, in rat debridement and keratectomy wounds (Hutcheon et al., 2005). We found little Smad activation in the debridement wound, while active Smad was elevated in the epithelial cells covering the keratectomy wound area. This activation peaked at 2 days and persisted for 1 week. Jung and coworkers (Huh et al., 2009a, 2009b) saw similar results comparing TGF-β ββ-signaling proteins in debridement and full-thickness wounds in chickens. Interestingly, most of the stromal TGF-ββ β signaling appeared to be through the p38 MAP kinase rather than the Smad pathway.

One of the common themes in many investigations of corneal wound repair is the deposition of temporary or provisional matrix components. These matrix components include fibronectin (Fujikawa et al., 1981; Suda et al., 1981), tenescin C (Tervo et al., 1991; van Setten et al., 1992), SPARC (Berryhill et al., 2003; Latvala et al., 1996) latent TGF-β binding proteins (Schlotzer-Schrehardt et al., 2001), osteopontin (Miyazaki et al., 2008), and TSP-1 (Hiscott et al., 1999). These matrix components, as a whole, appear to provide an ideal environment that promotes migration and transformation of cells required for wound repair. We hypothesize that following wounding a variety of matrix components are synthesized that stimulate migration of both fibroblasts and blood derived cells into the wound area. In the wound area, the cells are exposed to a “sink” of active TGF-β, which can stimulate the formation of myofibroblasts and wound repair. Unfortunately, this wound healing can lead to the formation of a scar. In contrast, in wounds where the basement membrane is not damaged the extent of newly synthesized matrix materials is confined and the amount of active TGF-β is lower. Thus, when cells migrate into the wound area they are not met by an environment that promotes myofibroblast formation and no scar is generated.

We examine the effect of the basement membrane in two corneal wound models.

Thrombospondin-1 is deposited to a far greater extent when the basement membrane is absent.

Myofibroblasts are observed only when basement membrane is damaged.

Myofibroblasts and thrombospondin-1 appear to co-localize.

Thrombospondin-1 may be part of a provisional matrix that stimulates myofibroblast formation.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH/NEI Grant No. R01 EY05665 to JDZ.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agah A, Kyriakides TR, Lawler J, Bornstein P. The lack of thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) dictates the course of wound healing in double-TSP1/TSP2-null mice. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:831–839. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64243-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baenziger NL, Brodie GN, Majerus PW. A thrombin-sensitive protein of human platelet membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68:240–243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.1.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berryhill BL, Kane B, Stramer BM, Fini ME, Hassell JR. Increased SPARC accumulation during corneal repair. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein P. Thrombospondins as matricellular modulators of cell function. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:929–934. doi: 10.1172/JCI12749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein P, Agah A, Kyriakides TR. The role of thrombospondins 1 and 2 in the regulation of cell-matrix interactions, collagen fibril formation, and the response to injury. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Wu HK, Bruce A, Wollenberg K, Panjwani N. Detection of differentially expressed genes in healing mouse corneas, using cDNA microarrays. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2897–2904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson CB, Lawler J, Mosher DF. Structures of thrombospondins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:672–686. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7484-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatila K, Ren G, Xia Y, Huebener P, Bujak M, Frangogiannis NG. The role of the thrombospondins in healing myocardial infarcts. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2007;5:21–27. doi: 10.2174/187152507779315813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Herndon ME, Lawler J. The cell biology of thrombospondin-1. Matrix Biol. 2000;19:597–614. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford SE, Stellmach V, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Ribeiro SM, Lawler J, Hynes RO, Boivin GP, Bouck N. Thrombospondin-1 is a major activator of TGF-beta1 in vivo. Cell. 1998;93:1159–1170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81460-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby I, Skalli O, Gabbiani G. Alpha-smooth muscle actin is transiently expressed by myofibroblasts during experimental wound healing. Lab Invest. 1990;63:21–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmouliere A, Geinoz A, Gabbiani F, Gabbiani G. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in granulation tissue myofibroblasts and in quiescent and growing cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:103–111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangogiannis NG, Ren G, Dewald O, Zymek P, Haudek S, Koerting A, Winkelmann K, Michael LH, Lawler J, Entman ML. Critical role of endogenous thrombospondin-1 in preventing expansion of healing myocardial infarcts. Circulation. 2005;111:2935–2942. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. The cellular basis of hepatic fibrosis. Mechanisms and treatment strategies. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1828–1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306243282508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa LS, Foster CS, Harrist TJ, Lanigan JM, Colvin RB. Fibronectin in healing rabbit corneal wounds. Lab Invest. 1981;45:120–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscott P, Armstrong D, Batterbury M, Kaye S. Repair in avascular tissues: fibrosis in the transparent structures of the eye and thrombospondin 1. Histol Histopathol. 1999;14:1309–1320. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscott P, Seitz B, Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Naumann GO. Immunolocalisation of thrombospondin 1 in human, bovine and rabbit cornea. Cell Tissue Res. 1997;289:307–310. doi: 10.1007/s004410050877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo C, Shankland SJ, Pichler RH, Couser WG, Johnson RJ. Thrombospondin 1 precedes and predicts the development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis in glomerular disease in the rat. Kidney Int. 1998;53:302–311. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh MI, Chang Y, Jung JC. Temporal and spatial distribution of TGF-beta isoforms and signaling intermediates in corneal regenerative wound repair. Histol Histopathol. 2009a;24:1405–1416. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh MI, Kim YH, Park JH, Bae SW, Kim MH, Chang Y, Kim SJ, Lee SR, Lee YS, Jin EJ, Sonn JK, Kang SS, Jung JC. Distribution of TGF-beta isoforms and signaling intermediates in corneal fibrotic wound repair. J Cell Biochem. 2009b;108:476–488. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheon AE, Guo XQ, Stepp MA, Simon KJ, Weinreb PH, Violette SM, Zieske JD. Effect of wound type on Smad 2 and 4 translocation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2362–2368. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV, Barry-Lane PA, Petroll WM, Olsen DR, Cavanagh HD. Inhibition of corneal fibrosis by topical application of blocking antibodies to TGF beta in the rabbit. Cornea. 1997;16:177–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV, Petroll WM, Barry PA, Cavanagh HD. Expression of alpha-smooth muscle (alpha-SM) actin during corneal stromal wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:809–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV, Rodrigues MM, Herman IM. Characterization of avascular corneal wound healing fibroblasts. New insights into the myofibroblast. Am J Pathol. 1987;127:140–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakides TR, Maclauchlan S. The role of thrombospondins in wound healing, ischemia, and the foreign body reaction. J Cell Commun Signal. 2009;3:215–225. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0077-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latvala T, Puolakkainen P, Vesaluoma M, Tervo T. Distribution of SPARC protein (osteonectin) in normal and wounded feline cornea. Exp Eye Res. 1996;63:579–584. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler J. The functions of thrombospondin-1 and-2. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:634–640. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung LL. Role of thrombospondin in platelet aggregation. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:1764–1772. doi: 10.1172/JCI111595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki K, Okada Y, Yamanaka O, Kitano A, Ikeda K, Kon S, Uede T, Rittling SR, Denhardt DT, Kao WW, Saika S. Corneal wound healing in an osteopontin-deficient mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:1367–1375. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller-Pedersen T, Cavanagh HD, Petroll WM, Jester JV. Neutralizing antibody to TGFbeta modulates stromal fibrosis but not regression of photoablative effect following PRK. Curr Eye Res. 1998;17:736–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Ullrich JE, Gurusiddappa S, Frazier WA, Hook M. Heparin-binding peptides from thrombospondins 1 and 2 contain focal adhesion-labilizing activity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26784–26789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Ullrich JE, Hook M. Thrombospondin modulates focal adhesions in endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:1309–1319. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.3.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Ullrich JE, Poczatek M. Activation of latent TGF-beta by thrombospondin-1: mechanisms and physiology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Ullrich JE, Schultz-Cherry S, Hook M. Transforming growth factor-beta complexes with thrombospondin. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:181–188. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AB. Molecular and cell biology of TGF-beta. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1998;24:111–119. doi: 10.1159/000057358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DD. Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol. 2005. THBS1 (thrombospondin-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saika S, Yamanaka O, Okada Y, Tanaka S, Miyamoto T, Sumioka T, Kitano A, Shirai K, Ikeda K. TGF beta in fibroproliferative diseases in the eye. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2009;1:376–390. doi: 10.2741/S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Zenkel M, Kuchle M, Sakai LY, Naumann GO. Role of transforming growth factor-beta1 and its latent form binding protein in pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73:765–780. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiyama E, Nakamura T, Cooper LJ, Kawasaki S, Hamuro J, Fullwood NJ, Kinoshita S. Unique distribution of thrombospondin-1 in human ocular surface epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1352–1358. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani N, Frazier WA. Thrombospondin-1, PECAM-1, and regulation of angiogenesis. Histol Histopathol. 1999;14:285–294. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit M, Velasco P, Riccardi L, Spencer L, Brown LF, Janes L, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Yano K, Hawighorst T, Iruela-Arispe L, Detmar M. Thrombospondin-1 suppresses wound healing and granulation tissue formation in the skin of transgenic mice. EMBO J. 2000;19:3272–3282. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda T, Nishida T, Ohashi Y, Nakagawa S, Manabe R. Fibronectin appears at the site of corneal stromal wound in rabbits. Curr Eye Res. 1981;1:553–556. doi: 10.3109/02713688109069181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K, Lawler J. The interaction of Thrombospondins with extracellular matrix proteins. J Cell Commun Signal. 2009;3:177–187. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0074-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon A, Tovey JC, Sharma A, Gupta R, Mohan RR. Role of transforming growth factor Beta in corneal function, biology and pathology. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10:565–578. doi: 10.2174/1566524011009060565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraboletti G, Roberts DD, Liotta LA. Thrombospondin-induced tumor cell migration: haptotaxis and chemotaxis are mediated by different molecular domains. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2409–2415. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.5.2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervo K, van Setten GB, Beuerman RW, Virtanen I, Tarkkanen A, Tervo T. Expression of tenascin and cellular fibronectin in the rabbit cornea after anterior keratectomy. Immunohistochemical study of wound healing dynamics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:2912–2918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uno K, Hayashi H, Kuroki M, Uchida H, Yamauchi Y, Oshima K. Thrombospondin-1 accelerates wound healing of corneal epithelia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315:928–934. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Setten GB, Koch JW, Tervo K, Lang GK, Tervo T, Naumann GO, Kolkmeier J, Virtanen I, Tarkkanen A. Expression of tenascin and fibronectin in the rabbit cornea after excimer laser surgery. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1992;230:178–183. doi: 10.1007/BF00164660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimar V. The transformation of corneal stromal cells to fibroblasts in corneal wound healing. Am J Ophthalmol. 1957;44:173–180. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(57)90445-2. discussion 180–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SE, Mohan RR, Ambrosio R, Jr, Hong J, Lee J. The corneal wound healing response: cytokine-mediated interaction of the epithelium, stroma, and inflammatory cells. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:625–637. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie XS, Li FY, Liu HC, Deng Y, Li Z, Fan JM. LSKL, a peptide antagonist of thrombospondin-1, attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis in rats with unilateral ureteral obstruction. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33:275–284. doi: 10.1007/s12272-010-0213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieske JD, Gipson IK. Protein synthesis during corneal epithelial wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieske JD, Guimaraes SR, Hutcheon AE. Kinetics of keratocyte proliferation in response to epithelial debridement. Exp Eye Res. 2001a;72:33–39. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieske JD, Higashijima SC, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Gipson IK. Biosynthetic responses of the rabbit cornea to a keratectomy wound. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987;28:1668–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieske JD, Hutcheon AE, Guo X, Chung EH, Joyce NC. TGF-beta receptor types I and II are differentially expressed during corneal epithelial wound repair. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001b;42:1465–1471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]