Abstract

Histone acetyltransferase 1 (HAT1) is an enzyme that is likely to be responsible for the acetylation that occurs on lysines 5 and 12 of the NH2-terminal tail of newly synthesized histone H4. Initial studies suggested that, despite its evolutionary conservation, this modification of new histone H4 played only a minor role in chromatin assembly. However, a number of recent studies have brought into focus the important role of both this modification and HAT1 in histone dynamics. Surprisingly, the function of HAT1 in chromatin assembly may extend beyond just its catalytic activity to include its role as a major histone binding protein. These results are incorporated into a model for the function of HAT1 in histone deposition and chromatin assembly.

HAT1 is the founding member of an expanding class of enzymes known as type B histone acetyltransferases (HATs). HATs are divided into two categories, type A and type B[1]. The type A HATs are nuclear enzymes that acetylate histones in the context of chromatin and their role in a variety of nuclear processes is well characterized. Traditionally, type B HATs are distinguished by their specificity for free histone substrates and their partial cytoplasmic localization. Based on these properties, type B HATs are thought to be involved in the acetylation of histones H3 and H4 that occurs rapidly upon their synthesis.

Acetylation of newly Synthesized Histones

In the mid-1970’s it was demonstrated that newly synthesized histone H4 is rapidly acetylated in the cytoplasm following its’ synthesis[2–4]. Subsequently, histone H3 was also shown to be acetylated rapidly after translation[4]. In the case of histone H4, acetylation of newly synthesized molecules was found to occur in a precise pattern that is highly conserved across eukaryotic evolution. Of the four lysine residues in the NH2-terminal tail that are subject to acetylation (at positions 5, 8, 12 and 16) there are high levels of modification at lysines 5 and 12 and little or no modification on lysines 8 and 16[5–8]. For histone H3, while it appears most organisms acetylate newly synthesized molecules, different patterns of acetylation can be found on the five NH2-terminal tail lysine residues that can be acetylated (at positions 9, 14,18, 23 and 27). For example, in flies (D. melanogaster), newly synthesized H3 is acetylated on lysines 14 and 23 while in tetrahymena (T. thermophila) lysines 9 and 14 are acetylated[7]. In S. cerevisiae, the situation is not clear. Pulse labeling experiments have shown that there are detectable levels of acetylation on newly synthesized histone H3 at all five lysine residues in the NH2-terminal tail[9]. However, acetylation of histone H3 on lysine 9 was shown to have a peak of abundance in S-phase that is dependent on the Asf1 histone chaperone[10]. Whether there are S-phase peaks of acetylation on the other lysines of the H3 NH2-termianl tail has not been determined.

With regard to the acetylation of newly synthesized histone H3, it is important to keep in mind that the proportion of new H3 molecules that are modified is small relative to histone H4. This is particularly true in mammalian cells, where this observation has been made using a variety of techniques[4, 5, 7, 11, 12]. Collectively, these studies indicate that roughly two-thirds of the new H3 molecules are unmodified. Whether the modified and unmodified new histone H3 molecules function in distinct ways during the chromatin assembly process has not been determined.

The NH2-terminal tail acetylation of the newly synthesized H3 and H4 molecules is a transient modification. Once these histones are transported into the nucleus and assembled into chromatin they are deacetylated during the process of chromatin maturation. During this maturation process, which lasts for 20–60 minutes in mammalian cells, histone H1 becomes associated with chromatin increasing the stability of nucleosomes[13].

In addition to the acetylation that occurs on the NH2-teriminal tails, acetylation of lysine residues in the core domain of newly synthesized histones H3 and H4 has recently been observed. The most well-characterized core domain acetylation occurs on lysine 56 of histone H3[14–16]. Lysine 56 is located at the end of the α-N helix of histone H3 and is a point of contact with DNA at the entry/exit point of the nucleosome. Thus, H3 lysine 56 acetylation may be capable of physically altering the contact between histone H3 and DNA[17]. Histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation occurs on newly synthesized histones, peaks during S-phase and is removed from histones in G2/M[16, 18, 19]. Mutations in yeast that alter H3 lysine 56 to mimic the constitutively unacetylated state (H3 K56R) result in cells that have increased levels of chromosomal breaks and are sensitive to DNA damaging agents[16, 18–26]. Evidence suggests that H3 lysine 56 acetylation plays an important role in both replication-coupled and replication-independent chromatin assembly as well as the reassembly of chromatin structure that accompanies DNA damage repair[16, 27–30]. A critical function of H3 lysine 56 acetylation in these processes may be to regulate interactions with histone chaperones as this modification has been shown to promote the association of H3 with both the CAF-1 and Rtt106 histone chaperones[31]. While originally thought to be limited to yeast, H3 lysine 56 acetylation is also found in higher eukaryotes and may play important roles in stem cell biology and cancer progression[32, 33].

A second site of histone core domain acetylation that that has been observed on newly synthesized histones is histone H4 lysine 91[34]. H4 lysine 91 lies along the interface between the H3/H4 tetramer and the H2A/H2B dimers. In fact, H4 lysine 91 normally forms a salt bridge with an aspartic acid residue in histone H2B[35]. Hence, neutralization of the positive charge of H4 lysine 91 may function to destabilize tetramer-dimer interactions and, thus, regulate the process of histone octamer assembly. Histone H4 lysine 91 is also a highly conserved modification that has been observed in human, bovine and yeast cells[34, 36, 37]. It is not known whether histone H4 lysine 91 acetylation is specifically found on newly synthesized histones. However, the fact that this modification was observed on molecules associated with a nuclear Hat1p-containing complex suggests that this may be the case. In addition, consistent with a role for H4 lysine 91 acetylation in chromatin assembly, genetic analysis of these mutations indicate that this modification functions in common pathways with histone chaperones Asf1 and CAF-1[34].

HAT1 and the acetylation of the histone H4 NH2-terminal tail

Despite its exceptional degree of evolutionary conservation, a specific function for the diacetylation of newly synthesized histone H4 on lysines 5 and 12 has not been identified. In fact, although the presence of this modification pattern is closely correlated with histone deposition, a number of studies suggest that this acetylation plays, at most, a minor role in chromatin assembly. For example, genetic studies in yeast involving mutants in which histone H4 lysines 5 and 12 are changed to arginine showed that the absence of this acetylation pattern had no effect on chromatin assembly and caused no defects in cell proliferation or viability[38–40]. In addition, replication-coupled chromatin assembly mediated by the CAF-1 complex was shown to function normally in the complete absence of the NH2-terminal tails of histones H3 and H4[41]. However, a recent study in Physarum polycephalum suggests that histone H4 lysine 5/12 acetylation promotes chromatin assembly in this organism. Thiriet and colleagues demonstrated that exogenously added histone proteins could be imported into the nucleus and assembled into chromatin. Taking advantage of this interesting model system, it was found that introducing histone H4 proteins with lysine to arginine substitutions at positions 5 and 12 dramatically reduced nuclear import. Importantly, changing these lysine residues to glutamine (thought to mimic constitutive acetylation) increased the rate of nuclear import[42]. A similar result was also recently reported using an in vitro nuclear translocation assay in HeLa cells where an H4 tail-EYFP fusion protein was more readily transported when lysines 5 and 12 were changed to glutamine to mimic constitutive acetylation[43]. These important results identify a specific step in the chromatin assembly pathway, namely histone import into the nucleus, that may be regulated by the diacetylation of newly synthesized histone H4.

The biochemical characterization of histone acetyltransferase activities from a variety of organisms suggested that the enzyme responsible for the acetylation of new histone H4 molecules was present in the cytoplasm[44–49]. A histone acetyltransferase specific for free H4 was first purified to homogeneity from S. cerevisiae cytoplasmic extracts[50]. The catalytic subunit of this enzyme was named Hat1p. This enzyme displayed an absolute specificity for free histones relative to nucleosomal substrates and modified histone H4 lysine 12 (the recombinant form of the enzyme acetylated both H4 lysines 5 and 12)[50, 51]. Similar activities isolated from other organisms also targeted free histone H4 on lysines 5 and 12[52–56]. While deletion of the HAT1 gene in yeast had no impact on cell proliferation or viability (similar to what is seen with the H4 K5,12R mutation), subsequent genetic analyses were also consistent with a role for HAT1 in the acetylation of newly synthesized histone H4[50, 51]. For example, the telomeric silencing defect observed in the absence of yeast Hat1p could be phenocopied by a mutation that altered histone H4 lysine 12 to arginine (mimicking a constitutively deacetylated state)[57]. In addition, the loss of HAT1 led to a decrease in the abundance of histone H4 acetylated at lysine 12 in chromatin localized near a DNA double strand break[58].

More direct evidence of a role for Hat1 in the acetylation of newly synthesized histone H4 has come from a number of recent studies that have shown that Hat1 is responsible for at least a portion of the acetylation that occurs on histone H4 lysines 5 and 12 in the pool of cytosolic histones. In chicken DT40 cells in which the HAT1 gene has been deleted the level of histone H4 lysine 5 and 12 acetylation in bulk chromatin does not change but there is a significant, but not complete, loss of these modifications on soluble histone H4[59]. A similar result was obtained in S. cerevisiae where treatment of the cells with hydroxyurea leads to cell cycle arrest in cells and an accumulation of soluble histones. In the absence of HAT1, there is a large decrease in histone H4 lysine 5 and 12 acetylation on these accumulated cytosolic histones[60]. The siRNA knockdown of Hat1 in mammalian cells has a more subtle effect on cytosolic histone H4 lysine 12 acetylation. The relatively minor effect on lysine 12 acetylation in these experiments may be due to the incomplete repression of Hat1 expression observed with the siRNA knockdown[61]. While definitive proof of Hat1s’ involvement in the acetylation of newly synthesized histone H4 will require the use of pulse-labeling techniques in cells genetically deleted for the HAT1 gene, the circumstantial evidence now strongly implicates Hat1 in this process. In addition, the accumulated evidence also strongly supports the idea that Hat1 is not the sole enzyme capable of acetylating newly synthesized histone H4 on lysines 5 and 12. Identifying other HATs that are capable of modifying the pool of new histones will significantly advance our efforts to understand the function of this conserved modification pattern.

A conserved core structure for type B histone acetyltransferases

Hat1 does not appear to function in isolation. However, in stark contrast to the large, multi-subunit complexes associated with type A HATs, Hat1 has been has been found to be a component of complexes that have remarkably simple subunit compositions[62]. In yeast, the core Hat1p complex appears to consist of Hat1p and Hat2p. This complex was originally purified from cytoplasmic extracts[50]. Similar complexes were subsequently isolated from a variety of other organisms (human, Xenopus, chicken and corn) where the Hat2p subunit is one of the homologous proteins Rbap46 or Rbap48 (Rbbp7/Rbbp4)[63–65]. Hat2p and related proteins are WD repeat proteins that are components of several types of complexes that are involved in histone metabolism such as CAF-1, HDAC complexes, NURF and PRC2[66–79]. These proteins have been shown to possess histone chaperone activity and, therefore, are thought to mediate the interactions of these varied complexes with histones[65, 80–83].

The basic subunit structure of the core Hat1 complex, a HAT associated with a histone chaperone, may be a conserved property of type B histone acetyltransferases. Rtt109p shares several important characteristics with Hat1p, which suggest that it be considered as the second member of the type B histone acetyltransferase family. This enzyme is responsible for the acetylation of newly synthesized histone H3 lysine 56 and contributes to the acetylation of several lysine residues in the H3 NH2-terminal tail. In addition, Rtt109p is specific for non-nucleosomal substrates. Interestingly, this enzyme is also found as part of a two-subunit complex with Vps75p, a NAP1-family histone chaperone. As seen for the association of Hat2p with Hat1p, the binding of Vps75p to Rtt109p has a dramatic effect on the enzyme’s catalytic activity[21–24, 84–89]. Hence, while there does not appear to be any structural similarity between the components of the Hat1 and Rtt109 complexes, the functional significance of the association of type B HATs with a partner histone chaperone has been conserved.

Another property shared between Hat1p and Rtt109p is a transient or substoichiometric interaction with Asf1p. Asf1p is necessary for the acetylation of histone H3 lysine 56 by Rtt109p. However, they do not appear to form a stable complex[22, 24, 27, 84, 90]. Surprisingly, the original type A HAT, Gcn5p, has also been implicated in the acetylation of the NH2-terminal tail of newly synthesized histone H3[10, 86, 91]. Gcn5p has been shown to exist in a number of high molecular weight complexes that are very different from the simple HAT/histone chaperone structure of the Hat1 and Rtt109 complexes[62, 92, 93]. However, Gcn5p was identified as the catalytic subunit of enzyme activity that specifically acetylated non-nucleosomal histone H3[94]. This complex did not appear to be related to the previously characterized Gcn5p-containing complexes. Therefore, it remains to be determined whether Gcn5p also associates with a histone chaperone to function in the acetylation of newly synthesized histone H3.

Nuclear HAT1-containing complexes

The core Hat1-Hat2(Rbap46/48) complex was originally purified from cytoplasmic extracts[50]. However, subsequent analyses indicated that Hat1 is actually a predominantly nuclear enzyme[95–97]. When in the nuclear compartment, this core Hat1 complex interacts with a number of other factors. The nature of these interactions provides important clues to the functional role of Hat1.

The most abundant form of nuclear Hat1p in yeast is the NuB4 complex (Nuclear type B HAT specific for H4). In addition to Hat1p and Hat2p, this complex also contains Hif1p. Importantly, Hif1p appears to be present in this complex at roughly stoichiometric levels with Hat1p and Hat2p[96, 97]. Hif1p is a member of the N1 family of histone chaperones and specifically interacts with histones H3 and H4. Hif1p can also participate in the deposition of histones onto DNA suggesting that Hat1p may be directly involved in the chromatin assembly process[96]. While Hif1p is clearly a component of the NuB4 complex, both genetic and biochemical data indicate that Hif1p also has functions in chromatin assembly that are independent of its association with Hat1p and Hat2p[97, 98].

As is the case for the core Hat1 complex, the NuB4 complex also appears to be evolutionarily conserved. This was first suggested by experiments involving the affinity purification of epitope tagged versions of human histones H3.1 and H3.3. For both histone H3 variants, not only the core Hat1 complex components, Hat1 and Rbap46/48, were found to co-purify but the human homolog of Hif1p, known as NASP (nuclear autoantigenic sperm protein) co-purified, as well[99]. While these results did not definitively determine whether Hat1 was physically associated with NASP, a more detailed study has recently used an epitope-tagged NASP to demonstrate that it interacts with Hat1 and Rbap46 in human cells[61]. Curiously, purification of a nuclear Hat1 complex from X. laevis did not detect the co-purification of N1 itself. Rather, in addition to the X. laevis Rbap46, a 14-3-3 protein was found to be a component of the nuclear Hat1 complex[64]. The function of the 14-3-3 protein/Hat1 interaction is not known but 14-3-3 proteins have been shown to directly interact with histone NH2-terminal tail domains in a modification specific manner to mediate the interaction of those histones with other HATs[100, 101].

While the NuB4 complex was originally isolated from yeast nuclear extracts, recent evidence from both yeast and human model systems suggests that interactions between the Hat1 core complex and an N1 family histone chaperone may also occur in the cytoplasm as an early step in the chromatin assembly pathway. These results derived from experiments involving the fractionation of epitope-tagged histones from cytoplasmic extracts[61]. One important caveat of these experiments is that nuclear proteins that are not stably associated with chromatin can readily leak out of the nucleus during the preparation of cytoplasmic extracts making it difficult to definitively determine sub-cellular localization. In addition, immuno-localization studies of the NuB4 complex components in both yeast and human cells show that these factors are highly enriched in the nucleus[65, 96, 97, 102, 103]. Therefore, it is likely that the bulk of the NuB4 complex is in the nucleus and that if this complex is found in the cytoplasm, it is likely to be a transient intermediate in the histone deposition process. An important question for future studies is whether the Hat1-containing complexes found in the cytoplasm and nucleus perform distinct activities or whether they are functionally related.

The NuB4 complex interacts with Asf1p, which plays a central role in controlling the flux of histones to the various chromatin assembly pathways. This interaction is also evolutionarily conserved having been detected in yeast, chicken and human cells[27, 61, 104, 105]. Asf1p appears to interact with the NuB4 complex at substoichiometric levels. When Asf1p is isolated by affinity purification, the presence of NuB4 complex components can be detected by Western blot analysis but are difficult to observe by either coomassie blue or silver staining[27]. Likewise, Asf1p is not readily apparent in purified Hat1p complexes[50, 65, 96, 106]. The interaction of Asf1p with the NuB4 complex requires the presence of both of its histone chaperones (Hat2p and Hif1p) and appears to be mediated by their interactions with histones[27, 61]. These histones are likely to interact with the NuB4 complex prior to their association with Asf1p based on the observation that the bulk of the histone H4 that is bound to Asf1p is acetylated on lysines 5 and 12[61, 105]. It is not clear where the interaction of the NuB4 complex with Asf1p occurs. As is the case for the NuB4 complex itself, the NuB4-Asf1p complex has been detected in human cytosolic extracts[61, 105, 107]. Again, as these factors are predominantly nuclear, the presence of these complexes in cytoplasmic extracts may represent a transient intermediate in the histone deposition process or result from an artifact of the fractionation process.

The Hat1 core complex also associates with nuclear factors independent of the NuB4 complex. Using a TAP-tagged Hat1p, Suter and colleagues, used affinity purification to identify proteins that physically interact with Hat1p. In addition to the expected Hat2p and Hif1p, all six subunits of the origin recognition complex (ORC) co-purified with Hat1p. Reciprocal affinity purification of the ORC complex then showed that only the Hat1 core complex (Hat1p and Hat2p) was actually associated with ORC. As was the case with Asf1p, ORC was present in levels far below those of Hat2p and Hif1p. A number of observations suggest that the physical interaction between the Hat1 core complex and ORC is functionally relevant. First, deletion of the HAT1 or HAT2 genes produced synthetic growth and viability defects when combined with temperature sensitive alleles of ORC2 and ORC5. Second, although the interaction between ORC and the Hat1 core complex did not vary throughout the cell cycle, Hat1p displayed an S-phase specific localization to chromatin at origins of replication. However, the role of the Hat1 core complex at origins is not known as the absence of Hat1p did not lead to any alterations in DNA replication[108]. Perhaps Hat1p acts to modify histone acetylation levels at origins (analogous to the role of Hbo1 in mammalian cells) or that the interaction with ORC may help to localize the Hat1 core complex to sites of DNA replication to participate in replication coupled chromatin assembly but that functional redundancy exists with other HATs or with the acetylation of histone H3 masking the effect of Hat1p loss[109, 110].

Histone chaperone activities of HAT1-containing complexes

Perhaps the most surprising components of the Hat1-containing complexes are histone H4 and histone H3. Enzymes are typically involved in transient interactions with their substrate. The enzyme will bind to the substrate, perform the relevant catalysis and then release the reaction product. However, Hat1 does not appear to function in a strictly catalytic fashion and appears to act in a somewhat stoichiometric manner by serving as a major histone interacting protein. This was first observed in experiments in which an epitope tagged histone H4 was affinity purified from yeast cytoplasmic extracts. The primary proteins associated with the cytoplasmic histone H4 were Hat1p, Hat2p, histone H3 and Kap123p (a karyopherin/importin)[111]. Histone H3 and H4 were also found to be associated with the NuB4 complex isolated from yeast nuclei[96]. Hat1 has also been found to co-purify with the soluble fraction of epitope tagged histones H3 and H4 from a variety of other organisms that include P. polycepharum, chickens and humans[42, 61, 99, 104, 112, 113]. These soluble histone fractions have been isolated from both cytosolic and nuclear extracts and the other components of the NuB4 complex (Hat2/Rbap48 and Hif1p/NASP) are often found associated with the histones as well. Hence, a picture has emerged in which Hat1 not only associates with histone H4 soon after its synthesis but also remains bound to the histone throughout much of the deposition pathway.

The stable association of Hat1 complexes with histones H3 and H4 raises a number of interesting issues. The first is the question of how Hat1 remains stably associated with histones H3 and H4. While the simple answer is that Hat1 remains bound to histones because of its association with histone chaperones, the real answer may be more complicated. For example, while Hat1 must interact with the histone H4 tail to acetylate lysines 5 and 12, it is not known whether the Hat1 active site remains associated with the H4 tail after modification. Acetylation of lysine 5 and/or 12 may result in a reorganization of the complex such that the histones become primarily associated with the histone chaperone subunits. This scenario is supported by the observation that the Hat1-Hat2(Rbap46) core complex may have multiple modes of interaction with histone H4. In isolation, the Rbap46/48 proteins do not bind to the H4 NH2-terminal tail domain but are capable of interacting with the first α-helix[65, 83]. However, in the context of the Hat1 core complex, Hat1 and Hat2(Rbap46) can stably interact with a peptide encoding the H4 NH2-terminal tail domain and this domain is required for the interaction of the complex with the full-length histone[50, 113]. Therefore, the components of the Hat1 core complex interact with histone H4 through multiple mechanisms and it will be important to determine whether the mode of interaction between the Hat1 core complex and histones is static or whether the interaction is dynamic depending on factors such as modification state of the histones or sub-cellular localization of the complex.

The second important issue is the question of why a type B HAT would remain stably associated with histones H3 and H4. One hypothesis is that the diacetylation of H4 lysines 5 and 12 plays a critical role in the chromatin assembly process and that during the pathway of histone deposition, the histones can be ambushed by histone deacetylases and this important modification pattern removed. In this model, Hat1 rides shotgun with the H3 and H4 to restore the diacetylation of histone H4. While this is an attractive hypothesis, the relatively weak impact of histone H4 lysine 5/12 acetylation on chromatin assembly, aside from a potential role in nuclear import, argues against it. Indeed, if the primary function of H4 lysine 5/12 acetylation is to promote nuclear import, it would not be necessary for Hat1 to remain associated with histones in the nucleus. Also, the acetylation of histone H3 lysine 56 has been shown to play important roles in chromatin assembly yet the Rtt109p/Vps75p complex does not display the same sustained association with histones that is seen for the Hat1 complexes.

There are a number of alternative explanations (that are non-mutually exclusive) for the stable association of Hat1 with histones. A related model is that, rather than protecting lysines 5 and 12 from deacetylation, the binding of Hat1 to histone H4 could prevent the inappropriate modification of other residues. H4 lysine 12 is positioned in the active site of Hat1, in part, through the alignment of H4 lysines 8 and 16 with acidic patches on Hat1[114]. In fact, the presence of positive charge at positions 8 and 16 is important for the catalytic activity of Hat1[115, 116]. If the H4 NH2-terminal tail remains bound in the active site of Hat1 following its acetylation, lysines 8 and 16 would be inaccessible to nuclear type A HATs. Given the important role of histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation in transcriptionally active chromatin, the Hat1 complexes may play an important role in maintaining proper patterns of epigenetic inheritance by preventing the acetylation of this residue until after chromatin is assembled[117].

Another scenario to explain the association of Hat1 complexes with histones H3 and H4 relates to the presence of multiple histone chaperones in these complexes. For example, the NuB4 complex, which contains both Hat2p(Rbap46) and Hif1p(NASP), also interacts with Asf1p[27, 61, 104]. It appears likely that all of these histone chaperones are binding to the histones simultaneously as the histones play an important role in mediating the interactions between in these multi-chaperone complexes[61, 97]. One of the primary functions of histone chaperones, which are negatively charged proteins, has been proposed to be the shielding of the highly concentrated positive charge of the histones to prevent inappropriate interactions[118]. However, structural studies of histone chaperones indicate that they make relatively limited contact with the histones that would not shield a significant fraction of the histones positive charge[119]. Therefore, it may be necessary for multiple chaperones to associate with histones H3 and H4 during the process of histone deposition. In fact, Hat1p itself is an acidic protein with an isoelectric point of 5.1. Therefore, in addition to its’ catalytic activity, Hat1 may also contribute to the histone chaperone activity of its associated complexes.

The importance of the histone chaperone function of Hat1p was highlighted by the recent demonstration that the catalytic activity of Hat1p is not sufficient for its function in vivo. Fusion of a nuclear export signal (NES) to yeast Hat1p effectively excluded the enzyme from the nucleus, with a concomitant increase in cytoplasmic localization. Also, the NES-Hat1p fusion did not diminish the catalytic activity of the enzyme. Importantly, the presence of this catalytically active Hat1p in the cytoplasm was not sufficient to compensate for the defect in telomeric silencing seen in the absence of Hat1p[120]. Hence, the ability of Hat1p to localize to the nucleus, and not just its enzymatic activity, contributes to its cellular function.

A model of HAT1 function

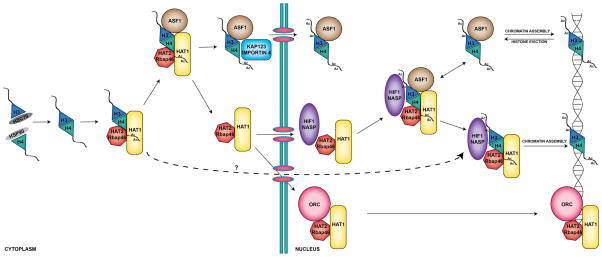

The original view of Hat1 as an enzyme that simply generated the diacetylation of newly synthesized histone H4 as an early step in histone deposition is not consistent with recent results. Rather, the role of Hat1 should be viewed as an integral component of the chromatin assembly process that may function at multiple steps. The basic features of a current model for Hat1 function are shown in Figure 1. The process of chromatin assembly is considered to be a step-wise process involving the sequential action of a series of enzymes and histone chaperones[118, 121]. Our understanding of these steps has become clearer with the identification of several discreet complexes containing soluble histones H3 and H4. The first factors that interact with newly synthesized H3 and H4 appear to be the heat shock factors HSC70 and HSP90, with HSC70 found with H3 and HSP90 with H4[43, 61]. These factors are likely to assist in the folding of the newly synthesized histone molecules into complexes with the appropriate stoichiometries[99, 122]. The evidence that these heat shock proteins function upstream of Hat1 comes from the observation that the histone H4 associated with these factors is not acetylated on lysine 12[61].

Figure 1. Model for the function of Hat1 in chromatin assembly.

The Hat1 core complex (Hat1 and Hat2/Rbap46) initially interacts with newly synthesized histones H3 and H4 and modifies the H4 by acetylating lysines 5 and 12. This complex may then interact with Asf1 and facilitate the association of the histones with their cognate nuclear import factor. The Hat1 core complex also transits to the nucleus where it is predominantly localized. Whether the Hat1 core complex can be co-transported with histone H3 and H4 is not known. Once inside the nucleus, the Hat1 core complex makes a number of interactions. The Hat1 core complex can interact with the origin recognition complex (ORC) and localize to origins of replication. The bulk of the Hat1 core complex forms the NuB4 complex with the addition of an N1 family histone chaperone (Hif1p or NASP). The NuB4 complex also appears to interact with Asf1. This interaction may be part of the pathway for deposition of newly synthesized histones or may be necessary for the modification of recycled histones. The NuB4 complex also functions independently of Asf1 and may be a component of a separate chromatin assembly pathway that functions in DNA repair-linked chromatin reassembly and may act in other chromatin assembly pathways, as well.

As all other soluble H3/H4-containing complexes that have been identified contain H4 lysine 12 acetylation, it is likely that interaction with Hat1 is the next step in the histone deposition pathway[61, 105]. It is also likely that this initial interaction between the Hat1-Hat2(Rbap46) complex and histones H3/H4 occurs in the cytoplasm. However, while there is conflicting evidence as to whether Hif1p(NASP) is associated with the cytoplasmic HAT1 complex, overall, the evidence suggests that the bulk of this interaction occurs in the nucleus and that a significant fraction of the cytoplasmic Hat1-Hat2(Rbap46) complex is independent of Hif1(NASP)[50, 61, 96–98, 107].

The fate of the Hat1 complex following its initial interaction with histones H3/H4 and the acetylation of H4 lysines 5 and 12 is not entirely clear. One possibility is that Asf1 interacts with the Hat1 complex to facilitate the transfer of the histones to the proper karyipherin/importin for nuclear import. Data showing that Asf1 interacts with both the Hat1-containing complexes and with the karyopherins/importins and that the histone H4 bound to the import factors is acetylated on lysine 12 supports this sequence of events[61, 105]. However, it is not known whether all of the histones associated with the cytoplasmic Hat1 are funneled into this Asf1/karyopheric pathway. Given that Hat1-containing complexes are stably associated with histones H3 and H4 in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus, it is not unreasonable to speculate that the Hat1 complexes may play a more direct role in the nuclear import of the histones[96, 111]. The presence of multiple mechanisms for histone nuclear import is supported by the fact that loss of the primary histone binding karyopherin/importin does not cause a dramatic defect in histone nuclear import[111].

Regardless of whether it is co-transported with histones H3 and H4 or whether it transits to the nucleus independently, the function of Hat1 once it is in the nucleus is not well understood. While in the nuclear compartment, Hat1, in all likelihood, exist in several distinct pools. For example, biochemical evidence indicates that a Hat1-Hat2(Rbap46) complex exists that does not contain a Hif1p(NASP) subunit and is consistent with the interaction of this complex with ORC occurring independently of Hif1p[98, 108]. It is undetermined whether the binding of the Hat1-Hat2(Rbap46) complex with the ORC complex occurs in the context of simultaneous binding to histone H3 and H4. In addition, it is not clear whether this interaction is related to replication-coupled chromatin assembly or whether this interaction is directly involved in the DNA replication process.

The most abundant form of Hat1p in the nucleus is apt to be in the form of the NuB4 complex[96]. In the context of chromatin assembly, the function of the NuB4 complex may be similar to that ascribed for the cytoplasmic HAT1 complex. That is, the NuB4 complex may be involved in directing newly synthesized histone H3/H4 complexes to Asf1 for subsequent distribution to replication-coupled and replication-independent chromatin assembly pathways. As discussed above, the majority of the NuB4 complex and Asf1 are nuclear and much of the histone H4 found associated with Asf1 is diacetylated[11, 105]. Another intriguing possibility is that the NuB4 complex may perform functions in the nucleus beyond its role in the metabolism of newly synthesized histones. In addition to histone deposition, Asf1 plays an important role in the eviction of histones from chromatin in the context of transcriptional regulation[119, 123–125]. It is not known how these histones are recycled into the pathway of chromatin assembly but the association of Asf1 with the NuB4 complex may be an indication that some recycled histone H4 may need to reacquire the deposition-related pattern of acetylation prior to its reassembly into chromatin.

While the available evidence suggests that the NuB4 complex functions immediately upstream of Asf1, the importance of this interaction is not known as Hat1 has not been demonstrated to directly influence either replication-coupled or replication-independent chromatin assembly. However, an analysis of the chromatin reassembly that accompanies the recombinational repair of a DNA double strand break has provided a model system to directly examine the role of the NuB4 complex. Using an inducible HO endonuclease that generates a single double strand break at the MAT locus, Tyler and colleagues used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to monitor levels of histone H3 near the double strand break. As expected, the levels of H3 decrease as single-strand resection occurs. As double strand break repair is completed, histone H3 levels are restored. Importantly, the restoration of H3 required the presence of Asf1p and histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation confirming the utility of this model for the study of DNA repair-linked chromatin assembly[126].

Loss of HAT1 and HIF1 had previously been shown to cause defects in the recombinational repair of DNA double strand breaks[96, 127]. An involvement in DNA repair is an evolutionarily conserved characteristic of these NuB4 complex components[59, 115, 128]. In addition, a direct involvement of the NuB4 complex in the recombinational repair of DNA double strand breaks was suggested by the fact that both Hat1p and Hif1p are recruited to chromatin near the sites of DNA damage[58]. By monitoring H3 levels at the MAT locus following an HO-induced DNA double strand break, the loss of Hat1p and Hif1p were both shown to result in a significant decrease in the reassembly of chromatin structure following DNA repair, marking the first direct demonstration of a role for the NuB4 complex in a chromatin assembly process. In addition, this system also provided evidence that the NuB4 complex does not exclusively function upstream of Asf1p. Combining deletions of either HAT1 or HIF1 with a deletion of ASF1 (in addition to specific mutations in histone H3) caused an increase in sensitivity to the HO-induced double strand break and an increased defect in DNA repair-linked chromatin reassembly[98]. Therefore, at least in the context of DNA repair, the NuB4 complex may perform functions in chromatin assembly that are independent of Asf1p. One possibility is that Hif1p, which has been shown to function in chromatin assembly assays in vitro, may be part of a distinct chromatin assembly pathway. Alternatively, the NuB4 complex may be capable of shuttling histones into other chromatin assembly pathways in the absence of Asf1p.

Our understanding of the function of Hat1 in chromatin assembly has grown dramatically in the past several years. However, many important issues remain to be addressed. Foremost among these is a reconciliation of the biochemical and genetic analyses of Hat1. At the biochemical level, Hat1 and its associated complexes are highly conserved and appear to be among the primary histone H3/H4 binding proteins in most eukaryotic organisms examined[42, 43, 61, 99, 104, 105, 112, 129]. In addition, Hat1 generates an evolutionarily conserved pattern of modification that is found on a very high percentage of newly synthesized histones[5, 11, 105]. Despite this apparent involvement in the histone deposition pathway, Hat1 is not essential for viability in any of the cell types in which it has been genetically deleted (S. cerevisiae, S. pombe and chicken DT40 cells)[50, 51, 59, 115]. Therefore, uncovering the complete picture of how Hat1 is integrated in the process of chromatin assembly, which may involve in vivo analyses in a wider variety of organisms, is an important goal. In addition, while it has now been shown that Hat1 is directly involved in the reassembly of chromatin structure that accompanies DNA double strand break repair, it is not known how this reassembly is related to other types of chromatin assembly pathways in the cell. Hence, it will be important to determine whether Hat1, and its associated factors, also participate in replication-coupled and replication-independent chromatin assembly. Finally, studies involving Hat1 have focused on its role in the formation and regulation of chromatin structure. However, it is now apparent that acetylation is a widely used modification that is involved in many cellular processes[36, 130, 131]. Probing the role of Hat1 in non-histone acetylation may uncover novel cellular functions for the original histone acetyltransferase.

Highlights.

Discussion of recent advances in our understanding of the type B histone acetyltransferase Hat1.

Hat1 acetylates newly synthesized histone H4 at lysines 5 and 12.

Hat1 and its complexes have been found to be major binding partners of soluble histones H3 and H4.

A model proposed for the activities of Hat1 complexes in the process of chromatin assembly.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Amy Knapp for critical reading of the manuscript. Work in my lab on Hat1 is funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM062970).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brownell JE, Allis CD. Special HATs for special occasions: linking histone acetylation to chromatin assembly and gene activation. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 1996;6:176–184. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruiz-Carillo A, Wangh LJ, Allfry V. Processing of newly synthesized histone molecules. Science. 1975;190:117–128. doi: 10.1126/science.1166303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louie AJ, Candido EP, Dixon GH. Enzymatic modifications and their possible roles in regulating the binding of basic proteins to DNA and in controlling chromosomal structure. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1974;38:803–819. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1974.038.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson V, Shires A, Tanphaichitr N, Chalkley R. Modifications to histones immediately after synthesis. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:471–483. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90282-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson LJ, Gu Y, Yakovleva T, Tong K, Barrows C, Strack CL, Cook RG, Mizzen CA, Annunziato AT. Modifications of H3 and H4 during Chromatin Replication, Nucleosome Assembly, and Histone Exchange. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9287–9296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512956200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chicoine LG, Schulman IG, Richman R, Cook RG, Allis CD. Nonrandom utilization of acetylation sites in histones isolated from Tetrahymena. Evidence for functionally distinct H4 acetylation sites. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:1071–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sobel RE, Cook RG, Perry CA, Annunziato AT, Allis CD. Conservation of deposition-related acetylation sites in newly synthesized histones H3 and H4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1237–1241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polo SE, Roche D, Almouzni G. New histone incorporation marks sites of UV repair in human cells. Cell. 2006;127:481–493. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo MH, Brownell JE, Sobel RE, Ranalli TA, Cook RG, Edmondson DG, Roth SY, Allis CD. Transcription-linked acetylation by Gcn5p of histones H3 and H4 at specific lysines. Nature. 1996;383:269–272. doi: 10.1038/383269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adkins MW, Carson JJ, English CM, Ramey CJ, Tyler JK. The histone chaperone anti-silencing function 1 stimulates the acetylation of newly synthesized histone H3 in S-phase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1334–1340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loyola A, Bonaldi T, Roche D, Imhof A, Almouzni G. PTMs on H3 variants before chromatin assembly potentiate their final epigenetic state. Mol Cell. 2006;24:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cousens LS, Alberts BM. Accessibility of newly synthesized chromatin to histone acetylase. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:3945–3949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Annunziato AT, Seale RL. Histone deacetylation is required for the maturation of newly replicated chromatin. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:12675–12684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu F, Zhang K, Grunstein M. Acetylation in histone H3 globular domain regulates gene expression in yeast. Cell. 2005;121:375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozdemir A, Spicuglia S, Lasonder E, Vermeulen M, Campsteijn C, Stunnenberg HG, Logie C. Characterization of lysine 56 of histone H3 as an acetylation site in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25949–25952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masumoto H, Hawke D, Kobayashi R, Verreault A. A role for cell-cycle-regulated histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation in the DNA damage response. Nature. 2005;436:294–298. doi: 10.1038/nature03714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimko JC, North JA, Bruns AN, Poirier MG, Ottesen JJ. Preparation of fully synthetic histone h3 reveals that acetyl-lysine 56 facilitates protein binding within nucleosomes. J Mol Biol. 2011;408:187–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maas NL, Miller KM, DeFazio LG, Toczyski DP. Cell cycle and checkpoint regulation of histone H3 K56 acetylation by Hst3 and Hst4. Mol Cell. 2006;23:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celic I, Masumoto H, Griffith WP, Meluh P, Cotter RJ, Boeke JD, Verreault A. The sirtuins hst3 and Hst4p preserve genome integrity by controlling histone h3 lysine 56 deacetylation. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1280–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller A, Yang B, Foster T, Kirchmaier AL. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen and ASF1 modulate silent chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via lysine 56 on histone H3. Genetics. 2008;179:793–809. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.084525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsubota T, Berndsen CE, Erkmann JA, Smith CL, Yang L, Freitas MA, Denu JM, Kaufman PD. Histone H3-K56 acetylation is catalyzed by histone chaperone-dependent complexes. Mol Cell. 2007;25:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han J, Zhou H, Horazdovsky B, Zhang K, Xu RM, Zhang Z. Rtt109 acetylates histone H3 lysine 56 and functions in DNA replication. Science. 2007;315:653–655. doi: 10.1126/science.1133234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Driscoll R, Hudson A, Jackson SP. Yeast Rtt109 promotes genome stability by acetylating histone H3 on lysine 56. Science. 2007;315:649–652. doi: 10.1126/science.1135862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider J, Bajwa P, Johnson FC, Bhaumik SR, Shilatifard A. Rtt109 is required for proper H3K56 acetylation: a chromatin mark associated with the elongating RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37270–37274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Recht J, Tsubota T, Tanny JC, Diaz RL, Berger JM, Zhang X, Garcia BA, Shabanowitz J, Burlingame AL, Hunt DF, Kaufman PD, Allis CD. Histone chaperone Asf1 is required for histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation, a modification associated with S phase in mitosis and meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6988–6993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601676103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Celic I, Verreault A, Boeke JD. Histone H3 K56 hyperacetylation perturbs replisomes and causes DNA damage. Genetics. 2008;179:1769–1784. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.088914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fillingham J, Recht J, Silva AC, Suter B, Emili A, Stagljar I, Krogan NJ, Allis CD, Keogh MC, Greenblatt JF. Chaperone control of the activity and specificity of the histone H3 acetyltransferase Rtt109. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4342–4353. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00182-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rufiange A, Jacques PE, Bhat W, Robert F, Nourani A. Genome-wide replication-independent histone H3 exchange occurs predominantly at promoters and implicates H3 K56 acetylation and Asf1. Mol Cell. 2007;27:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen CC, Carson JJ, Feser J, Tamburini B, Zabaronick S, Linger J, Tyler JK. Acetylated lysine 56 on histone H3 drives chromatin assembly after repair and signals for the completion of repair. Cell. 2008;134:231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan T, Liu CL, Erkmann JA, Holik J, Grunstein M, Kaufman PD, Friedman N, Rando OJ. Cell cycle- and chaperone-mediated regulation of H3K56ac incorporation in yeast. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Q, Zhou H, Wurtele H, Davies B, Horazdovsky B, Verreault A, Zhang Z. Acetylation of histone H3 lysine 56 regulates replication-coupled nucleosome assembly. Cell. 2008;134:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie W, Song C, Young NL, Sperling AS, Xu F, Sridharan R, Conway AE, Garcia BA, Plath K, Clark AT, Grunstein M. Histone h3 lysine 56 acetylation is linked to the core transcriptional network in human embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell. 2009;33:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das C, Lucia MS, Hansen KC, Tyler JK. CBP/p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 on lysine 56. Nature. 2009;459:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature07861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye J, Ai X, Eugeni EE, Zhang L, Carpenter LR, Jelinek MA, Freitas MA, Parthun MR. Histone H4 lysine 91 acetylation a core domain modification associated with chromatin assembly. Mol Cell. 2005;18:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cosgrove MS, Boeke JD, Wolberger C. Regulated nucleosome mobility and the histone code. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1037–1043. doi: 10.1038/nsmb851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basu A, Rose KL, Zhang J, Beavis RC, Ueberheide B, Garcia BA, Chait B, Zhao Y, Hunt DF, Segal E, Allis CD, Hake SB. Proteome-wide prediction of acetylation substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13785–13790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906801106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Eugeni EE, Parthun MR, Freitas MA. Identification of novel histone post-translational modifications by peptide mass fingerprinting. Chromosoma. 2003;112:77–86. doi: 10.1007/s00412-003-0244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Megee PC, Morgan BA, Mittman BA, Smith MM. Genetic analysis of histone H4: essential role of lysines subject to reversible acetylation. Science. 1990;247:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.2106160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang W, Bone JR, Edmondson DG, Turner BM, Roth SY. Essential and redundant functions of histone acetylation revealed by mutation of target lysines and loss of the Gcn5p acetyltransferase. Embo J. 1998;17:3155–3167. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma XJ, Wu J, Altheim BA, Schultz MC, Grunstein M. Deposition-related sites K5/K12 in histone H4 are not required for nucleosome deposition in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6693–6698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shibahara K, Verreault A, Stillman B. The N-terminal domains of histones H3 and H4 are not necessary for chromatin assembly factor-1- mediated nucleosome assembly onto replicated DNA in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7766–7771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ejlassi-Lassallette A, Mocquard E, Arnaud MC, Thiriet C. H4 replication-dependent diacetylation and Hat1 promote S-phase chromatin assembly in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:245–255. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-07-0633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alvarez F, Munoz F, Schilcher P, Imhof A, Almozuni G, Loyola A. Sequential establishment of marks on soluble histones H3 and H4. J Biol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.223453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopez-Rodas G, Tordera V, Sanchez del Pino MM, Franco L. Subcellular localization and nucleosome specificity of yeast histone acetyltransferases. Biochemistry. 1991;30:3728–3732. doi: 10.1021/bi00229a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lopez-Rodas G, Tordera V, Sanchez del Pino MM, Franco L. Yeast contains multiple forms of histone acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:19028–19033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lopez-Rodas G, Perez-Ortin JE, Tordera V, Salvador ML, Franco L. Partial purification and properties of two histone acetyltransferases from the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;239:184–190. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90825-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiegand RC, Brutlag DL. Histone acetylase from Drosophila melanogaster specific for H4. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:4578–4583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garcea RL, Alberts BM. Comparative studies of histone acetylation in nucleosomes, nuclei, and intact cells. Evidence for special factors which modify acetylase action. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:11454–11463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sures I, Gallwitz D. Histone-specific acetyltransferases from calf thymus Isolation, properties, and substrate specificity of three different enzymes. Biochemistry. 1980;19:943–951. doi: 10.1021/bi00546a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parthun MR, Widom J, Gottschling DE. The major cytoplasmic histone acetyltransferase in yeast: links to chromatin replication and histone metabolism. Cell. 1996;87:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kleff S, Andrulis ED, Anderson CW, Sternglanz R. Identification of a gene encoding a yeast histone H4 acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24674–24677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mingarro I, Sendra R, Salvador ML, Franco L. Site specificity of pea histone acetyltransferase B in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13248–13252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sobel RE, Cook RG, Allis CD. Non-random acetylation of histone H4 by a cytoplasmic histone acetyltransferase as determined by novel methodology. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18576–18582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolle D, Sarg B, Lindner H, Loidl P. Substrate and sequential site specificity of cytoplasmic histone acetyltransferases of maize and rat liver. FEBS Lett. 1998;421:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang L, Loranger SS, Mizzen C, Ernst SG, Allis CD, Annunziato AT. Histones in transit: cytosolic histone complexes and diacetylation of H4 during nucleosome assembly in human cells. Biochemistry. 1997;36:469–480. doi: 10.1021/bi962069i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richman R, Chicoine LG, Collini MP, Cook RG, Allis CD. Micronuclei and the cytoplasm of growing Tetrahymena contain a histone acetylase activity which is highly specific for free histone H4. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:1017–1026. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.4.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kelly TJ, Qin S, Gottschling DE, Parthun MR. Type B histone acetyltransferase Hat1p participates in telomeric silencing. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7051–7058. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7051-7058.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qin S, Parthun MR. Recruitment of the type B histone acetyltransferase Hat1p to chromatin is linked to DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3649–3658. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3649-3658.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barman HK, Takami Y, Ono T, Nishijima H, Sanematsu F, Shibahara K, Nakayama T. Histone acetyltransferase 1 is dispensable for replication-coupled chromatin assembly but contributes to recover DNA damages created following replication blockage in vertebrate cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:1547–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Poveda A, Sendra R. Site specificity of yeast histone acetyltransferase B complex in vivo. Febs J. 2008;275:2122–2136. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campos EI, Fillingham J, Li G, Zheng H, Voigt P, Kuo WH, Seepany H, Gao Z, Day LA, Greenblatt JF, Reinberg D. The program for processing newly synthesized histones H3.1 and H4. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1343–1351. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee KK, Workman JL. Histone acetyltransferase complexes: one size doesn't fit all. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:284–295. doi: 10.1038/nrm2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lusser A, Eberharter A, Loidl A, Goralik-Schramel M, Horngacher M, Haas H, Loidl P. Analysis of the histone acetyltransferase B complex of maize embryos. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4427–4435. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Imhof A, Wolffe AP. Purification and properties of the xenopus hat1 acetyltransferase: association with the 14-3-3 proteins in the oocyte nucleus [In Process Citation] Biochemistry. 1999;38:13085–13093. doi: 10.1021/bi9912490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Verreault A, Kaufman PD, Kobayashi R, Stillman B. Nucleosomal DNA regulates the core-histone-binding subunit of the human Hat1 acetyltransferase. Curr Biol. 1998;8:96–108. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tie F, Furuyama T, Prasad-Sinha J, Jane E, Harte PJ. The Drosophila Polycomb Group proteins ESC and E(Z) are present in a complex containing the histone-binding protein p55 and the histone deacetylase RPD3. Development. 2001;128:275–286. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muller J, Hart CM, Francis NJ, Vargas ML, Sengupta A, Wild B, Miller EL, O'Connor MB, Kingston RE, Simon JA. Histone methyltransferase activity of a Drosophila Polycomb group repressor complex. Cell. 2002;111:197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00976-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kuzmichev A, Nishioka K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Histone methyltransferase activity associated with a human multiprotein complex containing the Enhancer of Zeste protein. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2893–2905. doi: 10.1101/gad.1035902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qian YW, Lee EY. Dual retinoblastoma-binding proteins with properties related to a negative regulator of ras in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25507–25513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qian YW, Wang YC, Hollingsworth RE, Jr, Jones D, Ling N, Lee EY. A retinoblastoma-binding protein related to a negative regulator of Ras in yeast. Nature. 1993;364:648–652. doi: 10.1038/364648a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hassig CA, Fleischer TC, Billin AN, Schreiber SL, Ayer DE. Histone deacetylase activity is required for full transcriptional repression by mSin3A. Cell. 1997;89:341–347. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martinez-Balbas MA, Tsukiyama T, Gdula D, Wu C. Drosophila NURF-55, a WD repeat protein involved in histone metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:132–137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Taunton J, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. A mammalian histone deacetylase related to the yeast transcriptional regulator Rpd3p [see comments] Science. 1996;272:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Verreault A, Kaufman PD, Kobayashi R, Stillman B. Nucleosome assembly by a complex of CAF-1 and acetylated histones H3/H4. Cell. 1996;87:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang Y, Iratni R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Histone deacetylases and SAP18, a novel polypeptide, are components of a human Sin3 complex. Cell. 1997;89:357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wade PA, Jones PL, Vermaak D, Wolffe AP. A multiple subunit Mi-2 histone deacetylase from Xenopus laevis cofractionates with an associated Snf2 superfamily ATPase. Curr Biol. 1998;8:843–846. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang Y, Ng HH, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Bird A, Reinberg D. Analysis of the NuRD subunits reveals a histone deacetylase core complex and a connection with DNA methylation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1924–1935. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xue Y, Wong J, Moreno GT, Young MK, Cote J, Wang W. NURD, a novel complex with both ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling and histone deacetylase activities. Mol Cell. 1998;2:851–861. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Czermin B, Melfi R, McCabe D, Seitz V, Imhof A, Pirrotta V. Drosophila enhancer of Zeste/ESC complexes have a histone H3 methyltransferase activity that marks chromosomal Polycomb sites. Cell. 2002;111:185–196. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00975-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Suganuma T, Pattenden SG, Workman JL. Diverse functions of WD40 repeat proteins in histone recognition. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1265–1268. doi: 10.1101/gad.1676208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Song JJ, Garlick JD, Kingston RE. Structural basis of histone H4 recognition by p55. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1313–1318. doi: 10.1101/gad.1653308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Furuyama T, Dalal Y, Henikoff S. Chaperone-mediated assembly of centromeric chromatin in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6172–6177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601686103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vermaak D, Wade PA, Jones PL, Shi YB, Wolffe AP. Functional analysis of the SIN3-histone deacetylase RPD3-RbAp48-histone H4 connection in the Xenopus oocyte. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5847–5860. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Han J, Zhou H, Li Z, Xu RM, Zhang Z. Acetylation of lysine 56 of histone H3 catalyzed by RTT109 and regulated by ASF1 is required for replisome integrity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28587–28596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Han J, Zhou H, Li Z, Xu RM, Zhang Z. The Rtt109-Vps75 histone acetyltransferase complex acetylates non-nucleosomal histone H3. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14158–14164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Burgess RJ, Zhou H, Han J, Zhang Z. A role for Gcn5 in replication-coupled nucleosome assembly. Mol Cell. 2010;37:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Berndsen CE, Tsubota T, Lindner SE, Lee S, Holton JM, Kaufman PD, Keck JL, Denu JM. Molecular functions of the histone acetyltransferase chaperone complex Rtt109-Vps75. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:948–956. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Selth LA, Lorch Y, Ocampo-Hafalla MT, Mitter R, Shales M, Krogan NJ, Kornberg RD, Svejstrup JQ. An rtt109-independent role for vps75 in transcription-associated nucleosome dynamics. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4220–4234. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01882-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kolonko EM, Albaugh BN, Lindner SE, Chen Y, Satyshur KA, Arnold KM, Kaufman PD, Keck JL, Denu JM. Catalytic activation of histone acetyltransferase Rtt109 by a histone chaperone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20275–20280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009860107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Collins SR, Miller KM, Maas NL, Roguev A, Fillingham J, Chu CS, Schuldiner M, Gebbia M, Recht J, Shales M, Ding H, Xu H, Han J, Ingvarsdottir K, Cheng B, Andrews B, Boone C, Berger SL, Hieter P, Zhang Z, Brown GW, Ingles CJ, Emili A, Allis CD, Toczyski DP, Weissman JS, Greenblatt JF, Krogan NJ. Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature. 2007;446:806–810. doi: 10.1038/nature05649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sklenar AR, Parthun MR. Characterization of yeast histone H3-specific type B histone acetyltransferases identifies an ADA2-independent Gcn5p activity. BMC Biochem. 2004;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Grant PA, Duggan L, Cote J, Roberts SM, Brownell JE, Candau R, Ohba R, Owen-Hughes T, Allis CD, Winston F, Berger SL, Workman JL. Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes & Development. 1997;11:1640–1650. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Eberharter A, Sterner DE, Schieltz D, Hassan A, Yates JR, 3rd, Berger SL, Workman JL. The ADA complex is a distinct histone acetyltransferase complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6621–6631. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sklenar AR, Parthun MR. Characterization of yeast histone H3-specific type B histone acetyltransferases identifies an ADA2-independent Gcn5p activity. BMC Biochem. 2004;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ruiz-Garcia AB, Sendra R, Galiana M, Pamblanco M, Perez-Ortin JE, Tordera V. HAT1 and HAT2 proteins are components of a yeast nuclear histone acetyltransferase enzyme specific for free histone H4. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12599–12605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ai X, Parthun MR. The nuclear Hat1p/Hat2p complex: a molecular link between type B histone acetyltransferases and chromatin assembly. Mol Cell. 2004;14:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Poveda A, Pamblanco M, Tafrov S, Tordera V, Sternglanz R, Sendra R. Hif1 is a component of yeast histone acetyltransferase B, a complex mainly localized in the nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16033–16043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ge Z, Wang H, Parthun MR. Nuclear Hat1p Complex (NuB4) Components Participate in DNA Repair-linked Chromatin Reassembly. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:16790–16799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.216846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tagami H, Ray-Gallet D, Almouzni G, Nakatani Y. Histone H3.1 and H3.3 complexes mediate nucleosome assembly pathways dependent or independent of DNA synthesis. Cell. 2004;116:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Karam CS, Kellner WA, Takenaka N, Clemmons AW, Corces VG. 14-3-3 mediates histone cross-talk during transcription elongation in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zippo A, Serafini R, Rocchigiani M, Pennacchini S, Krepelova A, Oliviero S. Histone crosstalk between H3S10ph and H4K16ac generates a histone code that mediates transcription elongation. Cell. 2009;138:1122–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lebel EA, Boukamp P, Tafrov ST. Irradiation with heavy-ion particles changes the cellular distribution of human histone acetyltransferase HAT1. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;339:271–284. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0390-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Welch JE, Zimmerman LJ, Joseph DR, O'Rand MG. Characterization of a sperm-specific nuclear autoantigenic protein. I. Complete sequence and homology with the Xenopus protein, N1/N2. Biol Reprod. 1990;43:559–568. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Barman HK, Takami Y, Nishijima H, Shibahara K, Sanematsu F, Nakayama T. Histone acetyltransferase-1 regulates integrity of cytosolic histone H3–H4 containing complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;373:624–630. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jasencakova Z, Scharf AN, Ask K, Corpet A, Imhof A, Almouzni G, Groth A. Replication stress interferes with histone recycling and predeposition marking of new histones. Mol Cell. 2010;37:736–743. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Eberharter A, Lechner T, Goralik-Schramel M, Loidl P. Purification and characterization of the cytoplasmic histone acetyltransferase B of maize embryos. FEBS Lett. 1996;386:75–81. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Blackwell JS, Jr, Wilkinson ST, Mosammaparast N, Pemberton LF. Mutational analysis of H3 and H4 N termini reveals distinct roles in nuclear import. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20142–20150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701989200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Suter B, Pogoutse O, Guo X, Krogan N, Lewis P, Greenblatt JF, Rine J, Emili A. Association with the origin recognition complex suggests a novel role for histone acetyltransferase Hat1p/Hat2p. BMC Biol. 2007;5:38. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Iizuka M, Matsui T, Takisawa H, Smith MM. Regulation of replication licensing by acetyltransferase Hbo1. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1098–1108. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.1098-1108.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Iizuka M, Stillman B. Histone acetyltransferase HBO1 interacts with the ORC1 subunit of the human initiator protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23027–23034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mosammaparast N, Guo Y, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Pemberton LF. Pathways mediating the nuclear import of histones H3 and H4 in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:862–868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Drane P, Ouararhni K, Depaux A, Shuaib M, Hamiche A. The death-associated protein DAXX is a novel histone chaperone involved in the replication-independent deposition of H3.3. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1253–1265. doi: 10.1101/gad.566910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Saade E, Mechold U, Kulyyassov A, Vertut D, Lipinski M, Ogryzko V. Analysis of interaction partners of H4 histone by a new proteomics approach. Proteomics. 2009;9:4934–4943. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dutnall RN, Tafrov ST, Sternglanz R, Ramakrishnan V. Structure of the histone acetyltransferase Hat1: a paradigm for the GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase superfamily. Cell. 1998;94:427–438. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81584-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Benson LJ, Phillips JA, Gu Y, Parthun MR, Hoffman CS, Annunziato AT. Properties of the type B histone acetyltransferase Hat1: H4 tail interaction, site preference, and involvement in DNA repair. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:836–842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Makowski AM, Dutnall RN, Annunziato AT. Effects of acetylation of histone H4 at lysines 8 and 16 on activity of the Hat1 histone acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43499–43502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shahbazian MD, Grunstein M. Functions of site-specific histone acetylation and deacetylation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:75–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.162114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Das C, Tyler JK, Churchill ME. The histone shuffle: histone chaperones in an energetic dance. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:476–489. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Park YJ, Luger K. Histone chaperones in nucleosome eviction and histone exchange. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mersfelder EL, Parthun MR. Involvement of Hat1p (Kat1p) catalytic activity and subcellular localization in telomeric silencing. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29060–29068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802564200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Corpet A, Almouzni G. Making copies of chromatin: the challenge of nucleosomal organization and epigenetic information. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bowman A, Ward R, Wiechens N, Singh V, El-Mkami H, Norman DG, Owen-Hughes T. The histone chaperones Nap1 and Vps75 bind histones H3 and H4 in a tetrameric conformation. Mol Cell. 41:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Adkins MW, Howar SR, Tyler JK. Chromatin disassembly mediated by the histone chaperone Asf1 is essential for transcriptional activation of the yeast PHO5 and PHO8 genes. Mol Cell. 2004;14:657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kim HJ, Seol JH, Han JW, Youn HD, Cho EJ. Histone chaperones regulate histone exchange during transcription. Embo J. 2007;26:4467–4474. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Schwabish MA, Struhl K. Asf1 mediates histone eviction and deposition during elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2006;22:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chen CC, Tyler J. Chromatin reassembly signals the end of DNA repair. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3792–3797. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.24.7188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Qin S, Parthun MR. Histone H3 and the histone acetyltransferase Hat1p contribute to DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:8353–8365. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.23.8353-8365.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, McDonald ER, 3rd, Hurov KE, Luo J, Bakalarski CE, Zhao Z, Solimini N, Lerenthal Y, Shiloh Y, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ. ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science. 2007;316:1160–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.1140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Parthun MR. Hat1: the emerging cellular roles of a type B histone acetyltransferase. Oncogene. 2007;26:5319–5328. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kim SC, Sprung R, Chen Y, Xu Y, Ball H, Pei J, Cheng T, Kho Y, Xiao H, Xiao L, Grishin NV, White M, Yang XJ, Zhao Y. Substrate and functional diversity of lysine acetylation revealed by a proteomics survey. Mol Cell. 2006;23:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yang XJ, Seto E. Lysine acetylation: codified crosstalk with other posttranslational modifications. Mol Cell. 2008;31:449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]