Abstract

Background

Pathological gambling (PG) is a form of behavioural addiction that has been associated with elevated impulsivity and also cognitive distortions in the processing of chance, probability and skill. We sought to assess the relationship between the level of cognitive distortions and state and trait measures of impulsivity in treatment-seeking pathological gamblers.

Method

Thirty pathological gamblers attending the National Problem Gambling Clinic, the first National Health Service clinic for gambling problems in the UK, were compared with 30 healthy controls in a case-control design. Cognitive distortions were assessed using the Gambling-Related Cognitions Scale (GRCS). Trait impulsivity was assessed using the UPPS-P, which includes scales of urgency, the tendency to be impulsive in positive or negative mood states. Delay discounting rates were taken as a state measure of impulsive choice.

Results

Pathological gamblers had elevated impulsivity on several UPPS-P subscales but effect sizes were largest (Cohen's d>1.4) for positive and negative urgency. The pathological gamblers also displayed higher levels of gambling distortions, and elevated preference for immediate rewards, compared to controls. Within the pathological gamblers, there was a strong relationship between the preference for immediate rewards and the level of cognitive distortions (R2=0.41).

Conclusions

Impulsive choice in the gamblers was correlated with the level of gambling distortions, and we hypothesize that an impulsive decision-making style may increase the acceptance of erroneous beliefs during gambling play.

Keywords: Behavioural addiction, decision making, delay discounting, problem gambling, risk taking

Introduction

Gambling is a recreational activity that becomes disordered in approximately 0.9% of the British population using DSM criteria (Wardle et al. 2010). There is extensive clinical and pathophysiological overlap between pathological gambling (PG) and the substance use disorders (Potenza, 2006; Frascella et al. 2010), prompting a probable reclassification of PG among the addictions in the forthcoming DSM-V (Mitzner et al. 2010; Bowden-Jones & Clark, in press). PG is thought to arise through a combination of biological, social and psychological risk factors (Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002; Sharpe, 2002). One of the defining features of gamblers' cognition is the tendency to overestimate the chances of winning, due to variety of cognitive distortions in the processing of chance, skill and probability (Ladouceur & Walker, 1996; Clark, 2010). Indeed, it is unclear whether these distortions have an obvious parallel in substance use disorders (Xian et al. 2008). Using psychometric measures of gambling distortions, such as the Gambling-Related Cognitions Scale (GRCS; Raylu & Oei, 2004a) or the Gambling Beliefs Questionnaire (GBQ; Steenbergh et al. 2002), several studies have reported elevated levels of distorted cognitions in individuals with disordered gambling compared to those without gambling problems (Miller & Currie, 2008; Emond & Marmurek, 2010; Myrseth et al. 2010). These cognitions are attenuated by treatment (Breen et al. 2001), and higher baseline scores predicted poorer outcome in a Gambler's Anonymous programme (Oei & Gordon, 2008).

Studies using personality measures and neurocognitive tests have also highlighted changes in impulsivity in PG. Scores on the Barratt Impulsivity Scale and the Eysenck Impulsivity Venturesomeness Empathy (IVE) scale reliably increased in case-control studies (Blaszczynski et al. 1997; Petry, 2001b; Nower et al. 2004; Lawrence et al. 2009a), and prospective studies have confirmed that high impulsivity during adolescence predicts later gambling problems (Vitaro et al. 1999; Slutske et al. 2005). Rather than being a unidimensional construct, impulsivity is being increasingly viewed as a constellation of traits, including a lack of planning or forethought, reduced perseverance and the seeking of novel or intense sensory experiences (Evenden, 1999; Verdejo-Garcia et al. 2008). Recent research has also identified a fourth impulsivity component, labelled ‘urgency’: the tendency to engage in impulsive acts during intense mood states. This construct was initially identified by Whiteside & Lynam (2001) using a composite of the Barratt and Eysenck scales and the Zuckerman Sensation Seeking Scale, and subsequent work by Cyders, Smith and colleagues (Cyders & Smith, 2008b) has distinguished positive and negative aspects of urgency. The urgency construct is profoundly relevant to gambling behaviour, as it is known that many gamblers are motivated to gamble to alleviate states of depression, stress or boredom (Jacobs, 1986), but simultaneously, positive mood (perhaps associated with hypomania or dramatic wins) may also prompt gambling sprees (Cummins et al. 2009; Lloyd et al. 2010). Although positive and negative urgency are moderately correlated and both are related to a range of risky behaviours (Cyders & Smith, 2008b), there are some differential effects. Positive urgency predicted longitudinal increases in gambling behaviour across university (Cyders & Smith, 2008a), and changes in risk taking and alcohol consumption following positive mood induction (Cyders et al. 2010), whereas negative urgency is associated with bulimic symptoms (Anestis et al. 2007) and tobacco cravings (Billieux et al. 2007).

Impulsivity can also be assessed in the laboratory using a variety of neurocognitive tasks. The delay discounting paradigm assesses impulsive choice by presenting a series of decisions between a smaller reward available soon (or immediately), and larger rewards available after a longer delay (Bickel & Marsch, 2001; Reynolds, 2006). Indifference points obtained from varying one of the decision parameters (e.g. the delay to the larger reward) can be fitted to a hyperbolic discounting curve, allowing derivation of a parameter k that indicates the steepness of the discounting function. Impulsive subjects show enhanced preference for the smaller immediate rewards and steeper discounting of delayed outcomes (i.e. higher k values), and several studies have described such a tendency in treatment-seeking and community groups with disordered gambling (Petry, 2001a; Alessi & Petry, 2003; Dixon et al. 2003; Ledgerwood et al. 2009).

Although impulsivity and gambling-related cognitive distortions have been described in pathological gamblers, the links between these constructs has received minimal attention. In an undergraduate sample comprising a range of gambling problems, the Eysenck Impulsivity score predicted higher scores on the GBQ (MacKillop et al. 2006), and a similar relationship was reported between Barratt scores and a measure of cognitive distortions that apply across many forms of psychopathology, such as personalization of negative events and all-or-none thinking (Mobini et al. 2007). We reasoned that an impulsive style of decision making may increase a gambler's tendency to accept erroneous beliefs about gambling over more ‘rational’ alternative interpretations that reflect more accurately the nature of chance. As such, the primary focus of the present study was to assess the degree of coupling between gambling-related cognitive distortions and state and trait indices of impulsivity, in participants with PG. Gamblers were recruited through the National Problem Gambling Clinic in London, which is the first (and only) National Health Service treatment facility for gambling in the UK. Given the limited treatment facilities for gambling prior to the opening of the clinic in 2008, there are few data available on the clinical characteristics and preferred forms of gambling of treatment-seeking gamblers in the UK, and it is vital to study gambling at a national level given the pronounced cultural and legislative heterogeneity in gambling practices across countries (Raylu & Oei, 2004b). A secondary objective was therefore to replicate prior findings, primarily from Australian and North American studies, of increased levels of gambling distortions, self-reported impulsivity, and discounting of delayed rewards in PG.

Method

Participants

Pathological gamblers (n=30) were recruited from the National Problem Gambling Clinic (28 males, two females; mean age=40.1 years, s.d.=12.3, range 21–60) and compared with community-recruited healthy controls (28 males, two females; mean age=35.8 years, s.d.=12.2, range 19–60). The protocol was approved by the Cambridge Local Research Ethics Committee (09/H0305/77) and all volunteers provided written informed consent. Participants were reimbursed for their time and travel expenses. The two groups did not differ in age (t=1.33, p=0.187), years of education (t=1.42, p=0.160) or errors committed on the National Adult Reading Test (NART; Nelson & Willison, 1991), which provides an estimate of verbal IQ (t=1.31, p=0.190). Inclusion criteria for the PG group were: DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for PG, and age 18–60 years. PG was confirmed using the Massachusetts Gambling Screen (MAGS; Shaffer et al. 1994), which indexes the DSM-IV criteria, in conjunction with a score of ⩾8 on the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI; Ferris & Wynne, 2001). Exclusion criteria for both groups were: history of neurological illness, previous psychiatric hospitalization, current pharmacotherapy and significant physical illness. Among the controls, 27 had a PGSI score of 0 and had never gambled; two scored 1 on the PGSI and one scored 2.

The PG participants were recruited as a convenience sample, and comprised three subgroups in terms of their treatment profile: 15 gamblers (50%) were tested prior to receiving any treatment, seven (23%) were currently receiving treatment and eight (27%) had recently completed a 10-session course of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). In the PG group, the presence of other current and lifetime diagnoses of mental illness was assessed by a semi-structured interview using the ICD-10, in conjunction with the computerized version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (e-MINI; Medical Outcome Systems, USA) (Sheehan et al. 1998). Any discrepancies between these measures were resolved through discussion with the lead psychiatrist (H.B.J.) and further review of the medical records. Ten cases met current or lifetime diagnoses of major depressive disorder (six current, four lifetime). Two cases recorded current generalized anxiety disorder. For substance use disorders, one case met lifetime cannabis dependence, one case lifetime alcohol dependence, and two cases current alcohol dependence. The healthy controls recorded no lifetime or current mental health problems on the e-MINI screen.

The various forms of gambling that were played were assessed with a modified version of item 1 from the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Lesieur & Blume, 1987); in addition, the PG participants were asked which form they considered most problematic for them. Sixty per cent of the PG group considered fixed odds betting terminals (FOBTs) to represent their problematic form of gambling. The other preferred games were sports betting (16%), internet poker or blackjack (7%), slot machines (10%), and casino games (7%). Convergent data were obtained from games played once a week or more (SOGS item 1) (individual participants may endorse more than one form, so the total does not sum to 100%): gaming machines (59%), betting on horses (52%), lottery (41%), sports betting (38%), card games (24%), casino games (17%), bingo (7%), bowling/pool (7%) or stock market (3%). In examining the relationship status of the participants, the modal status in the PG group was single (50%), 30% were in a steady relationship, 13% were married and 7% were divorced. Among controls, the modal status was married (47%), with 23% single, 17% in a steady relationship, 10% divorced and 3% widowed. Both groups were predominately of British nationality (PG: 97%; controls: 88%). Employment status was similar in both groups; in the PG group, 61% were employed full time, 7% students, 10% self-employed, 3% retired and 17% unemployed. In the controls, 43% were employed full time, 17% students, 3% self-employed, 17% unemployed and 13% in part-time employment. The PG group rated the largest amount of money gambled in a single day, on a four-point scale: £10–£100 (6%), £100–£1000 (17%), £1000–£10 000 (60%), over £10 000 (17%). Current level of debt ranged from £0 to £80 000: 23% had no debt due to bail-out; in the gamblers with current debt, this debt ranged from £600 to £80 000 (mean £25 557).

Procedure

All participants attended a single test session in a quiet laboratory or treatment room, where they completed a cognitive assessment and questionnaire measures of clinical and personality measures.

Kirby Monetary Choice Questionnaire (MCQ; Kirby et al. 1999)

The MCQ is a measure of delay discounting comprising 27 hypothetical choices between a smaller reward available immediately versus a larger reward available at some point in the future (e.g. ‘Would you prefer £15 today or £35 in 13 days?’). The larger reward varies across three levels of magnitude: small (£25–£35), medium (£50–£60) and large (£75–£80), deriving three k values that were averaged for the overall discounting rate. Given that the k parameter assumes an underlying hyperbolic discounting curve, an area under the curve (AUC) value was also extracted for each participant, as a parameter that is neutral to the underlying discounting function (Myerson et al. 2001).

UPPS-P Impulsive Behaviour Scale (Cyders et al. 2007)

This is a 59-item self-report questionnaire using a Likert scale from 1 (I agree strongly) to 4 (I disagree strongly) to assess five impulsivity subscales: Negative Urgency (e.g. ‘Sometimes when I feel bad, I can't seem to stop what I am doing even though it is making me feel worse’); Positive Urgency (e.g. ‘When overjoyed, I feel like I can't stop myself from going overboard’); (lack of) Planning (e.g. ‘I usually make up my mind through careful reasoning’ – negative loading); (lack of) Perseverance (e.g. ‘I finish what I start’ – negative loading); and Sensation Seeking (e.g. ‘I would enjoy the sensation of skiing very fast down a high mountain slope’).

GRCS (Raylu & Oei, 2004a)

The GRCS a 23-item self-report questionnaire using a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) to assess five subscales: Predictive Control (e.g. ‘Losses when gambling are bound to be followed by a series of wins’); Illusion of Control (e.g. ‘I have specific rituals and behaviours that increase my chances of winning’); Interpretive Bias (e.g. ‘Relating my winnings to my skill and ability makes me continue gambling’); Gambling Expectancies (e.g. ‘Gambling makes things seem better’); and Inability to Stop (e.g. ‘I'm not strong enough to stop gambling’).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were implemented in SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc., USA). A natural log transformation was applied to the discounting k values, to improve suitability for parametric analysis. Visual inspection of the discounting data led to exclusion of three participants' scores on this measure (one PG, two controls), who uniformly selected the larger reward across all delay (i.e. the pre-specified delays and amounts on the MCQ failed to isolate indifference points for these participants). Group comparisons on the GRCS and UPPS-P were performed by entering the component subscales into a multivariate ANOVA. A mixed-model ANOVA was used to compare k discounting values, with magnitude of the larger reward as a within-subjects factor. Within the PG group, Pearson's coefficients were used to assess univariate relationships between the UPPS-P, GRCS and Kirby MCQ variables, and a stepwise multiple linear regression assessed possible additive contributions of the UPPS-P and Kirby MCQ variables to predicting the level of cognitive distortions (with GRCS as the dependent variable).

Results

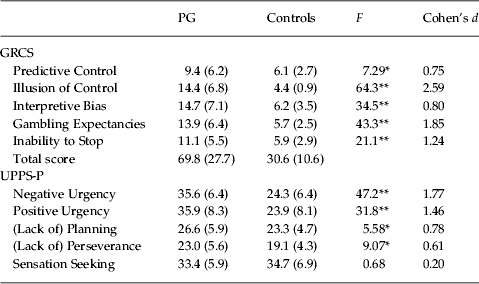

The PG group displayed a higher level of gambling-related cognitions (F5,54=13.1, p<0.001), with significant differences on all of the GRCS subscales (see Table 1). On the UPPS-P, the PG group displayed elevated impulsivity (F5,54=10.0, p<0.001), with significant differences on all subscales with the exception of Sensation Seeking (see Table 1). Effect sizes (Cohen's d) revealed stronger effects for the two urgency subscales (d=1.46–1.77) in comparison to the narrow impulsivity subscales (d=0.61–0.78).

Table 1.

Mean scores (s.d.) on the GRCS and UPPS-P Impulsivity Scale in the participants with pathological gambling (PG) and healthy controls

GRCS, Gambling-Related Cognitions Scale; s.d., standard deviation.

ANOVA degrees of freedom 1, 59.

p<0.05, ** p<0.005.

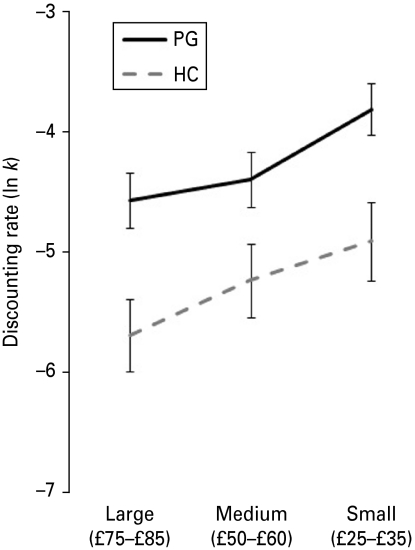

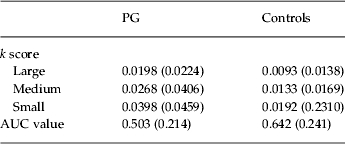

Choice behaviour on the delay discounting scale was analysed using a mixed-model ANOVA of group (PG, controls) by magnitude (small, medium, large). The PG group displayed higher k values than healthy controls (main effect of group: F1,55=8.02, p=0.006), indicating elevated impulsive choice in the PG group (see Fig. 1). All participants showed higher k values (steeper discounting) for smaller, compared to larger, delayed rewards (F1,55=23.2, p<0.001). This is consistent with a typical ‘magnitude effect’ (e.g. Chapman, 1996), and suggests that the PG participants are using similar cognitive mechanisms for making these inter-temporal decisions to the healthy controls. There was no interaction of group by magnitude (F1,55=0.894, p=0.412). In addition, the PG and healthy controls differed on the AUC measure for the discounting function (t55=2.3, p=0.025), a parameter that does not assume any underlying mathematical function. The AUC values are displayed in Table 2, alongside the untransformed k scores for comparison with previous studies with the MCQ.

Fig. 1.

Delay discounting (ln k) on the Monetary Choice Questionnaire (MCQ), in patients with pathological gambling (PG) and healthy controls (HC). Errors bars indicate standard error of the mean.

Table 2.

Untransformed delay discounting measures on the Monetary Choice Questionnaire (MCQ), in the participants with pathological gambling (PG) and healthy controls

AUC, Area under the curve.

Values given as mean (standard deviation).

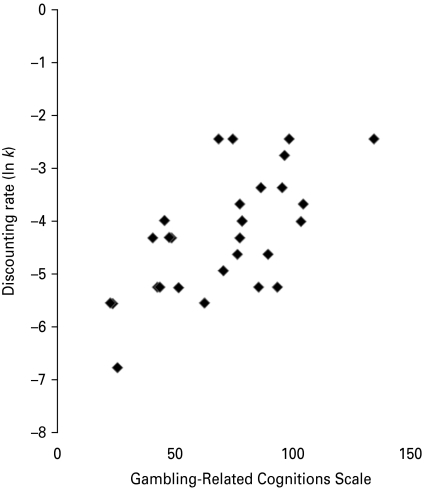

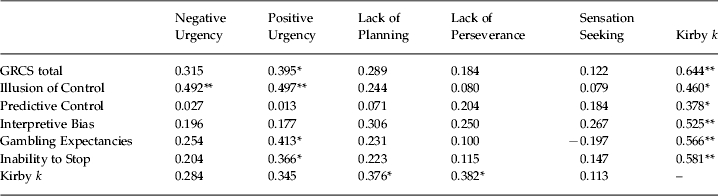

We examined univariate associations between delay discounting (average k), UPPS-P impulsivity and GRCS scores in the PG group. In keeping with previous work (e.g. Kirby et al. 1999; Mobini et al. 2007; Koff & Lucas, 2011), moderate associations were observed between the delay discounting rates and self-reported impulsivity (UPPS-P), with the highest coefficients observed on Lack of Planning (r=0.376, p=0.044) and Lack of Perseverance (r=0.382, p=0.041). A strong correlation was observed between impulsive choice on the delay discounting scale and the level of gambling cognitions (see Fig. 2), explaining 41% of the variance in the total GRCS score. Each of the GRCS subscale correlations was statistically significant (see Table 3). In light of a previous study showing that gambling distortions are attenuated by psychological treatment (Breen et al. 2001), we observed no significant difference in the GRCS scores in the three PG subgroups at different stages of treatment: pre-treatment group, mean GRCS=74.6 (s.d.=20.9); during treatment group, mean GRCS=71.4 (s.d.=37.2); post-treatment group, mean GRCS=59.5 (s.d.=30.6, F2,27=0.78, p=0.469). Notably, the correlation between the discount rate and the GRCS total remained highly significant after controlling for stage of treatment (partial coefficient r=0.612, p=0.001).

Fig. 2.

Delay discounting (ln k scores, averaged across the three magnitude levels) is correlated significantly with total score on the Gambling-Related Cognitions Scale (GRCS), in the pathological gamblers.

Table 3.

Univariate correlations (Pearson's r) between the delay discounting (Kirby k; n=29), Gambling-Related Cognitions Scale (GRCS) (n=30) and UPPS-P (n=30) in the pathological gamblers

p<0.05, ** p<0.005.

UPPS-P impulsivity was less clearly associated with the level of cognitive distortions in the PG group: Negative and Positive Urgency were both associated with Illusion of Control, and Positive Urgency was additionally correlated with the Gambling Expectancies and Inability to Stop subscales, and the GRCS total (see Table 3). To test whether the UPPS-P urgency scales added significantly to the discounting rates in the prediction of gambling distortions, a stepwise multiple regression model was run with the total GRCS score as the dependent variable, and the delay discounting rate, Positive Urgency and Negative Urgency as predictors. The k score was the only variable retained in the model as a significant predictor of the level of cognitive distortions (R2=0.415, overall F1,27=19.1, p<0.001, kβ=0.64). (The same conclusion was drawn using a hierarchical regression with the discounting rate entered at the first step and the Urgency scores entered at the second step: there was no significant change in the R2 between the two steps; overall R2=0.481.) We also explored the relationships between delay discounting (average k) and the GRCS score and UPPS-P subscales in the healthy controls. The total GRCS scores displayed moderate variability in the controls (minimum=23, maximum=60) and, as in the PG, impulsive choice on the delay discounting measure was predictive of the level of gambling distortions (r=0.431, p=0.022). The correlations between delay discounting and the UPPS-P subscales were not significant in the controls, although the coefficients for Negative (r=0.20) and Positive (r=0.34) Urgency, and Lack of Planning (r=0.21), were comparable to the strength of relationships observed in previous studies (Kirby et al. 1999; Mobini et al. 2007; Koff & Lucas, 2011).

Discussion

The present study is the first UK study to describe clinical and psychological data in treatment-seeking PG. A convenience sample of 30 gamblers recruited from the National Problem Gambling Clinic were predominantly male, well-educated (48% had entered higher education), and typically in full-time employment (61%). As expected, these gamblers participated in a range of games, with the preferred form of gambling being FOBTs in some 60% of the sample. These gaming machines (now known as category B2 gaming machines) are characterized by high stakes, high jackpots, and a rapid rate of play, and are a relatively new arrival on the UK gambling landscape. Although the national prevalence of FOBT play was low (4%) in the 2010 British Gambling Prevalence Survey (Wardle et al. 2010), FOBT play was the third most common form of gambling among the problem gamblers recruited in that survey (in 9%). Our data further highlight the attractiveness of these games in a treatment-seeking group with PG.

The major finding in the present dataset was of a relationship between impulsive choice on the delay discounting task and the level of gambling-related cognitive distortions. This was a particularly strong effect in the PG group, where discounting scores explained 41% of the variability in gambling distortions, and it was also observed at a significant level (19% shared variance) in the healthy controls. Group differences in impulsivity, and inaccurate beliefs about skill, chance and probability, are widely recognized in the literature on problem gambling, but the relationship between these putative aetiological mechanisms has received little attention. Our findings support a previous study in student gamblers (MacKillop et al. 2006), where the GBQ was correlated moderately (r=0.40) with Eysenck Impulsivity scores. We extend these findings into a treatment-seeking PG sample, and demonstrate that a state measure of impulsive choice is the stronger predictor of gambling distortions than self-reported impulsivity. This close linkage illustrates that gamblers with more ‘myopic’ (i.e. focused on the present) decision making and a reduced capacity to defer gratification are more susceptible to the diverse range of complex distortions that occur during play, such as beliefs in superstitions and rituals (GRCS Illusion of Control), the failure to appreciate independence of turns (GRCS Predictive Control), and expectancies that gambling will be exciting and/or relieve negative affect (GRCS Gambling Expectancies) (Toneatto et al. 1997; Raylu & Oei, 2004a). Indeed, delay discounting was significantly associated with all five of the GRCS subscale scores in the PG group. Many of these distortions can also be elicited in healthy, non-problem gamblers (Clark, 2010), and we saw that discounting rates were also predictive of GRCS scores in the healthy controls. We have reported previously that individual differences on the GRCS predicted neural responses to gambling ‘near-misses’ in healthy non-gamblers (Clark et al. 2009).

We were able to replicate several group differences reported previously in Australian and North American studies. First, the PG group reported more cognitive distortions on the GRCS, with significant group differences on each of the five subscales (Raylu & Oei, 2004a; Emond & Marmurek, 2010). Prospective data do not yet exist to arbitrate whether these cognitions predate the onset of problem gambling, or occur as a consequence of long-term gambling. Second, the PG group displayed elevated impulsivity on the UPPS-P questionnaire. Significant differences were observed on the two subscales of ‘narrow’ impulsivity (Lack of Premeditation and Lack of Perseverance) and also on the two Urgency subscales, but the effect sizes for the Urgency subscales were considerably larger. This is the first study to differentiate Positive Urgency and Negative Urgency in treatment-seeking PG, and our findings clearly emphasize the relevance of these constructs to PG. By inference, impulsive acts in problem gamblers may predominantly arise through an interaction with current affective state, perhaps through impaired emotion regulation mechanisms (Billieux et al. 2010; Cyders et al. 2010). Although Positive and Negative Urgency scales were correlated in the present data, it remains to be seen whether positive or negative mood states represent distinct pathways to risk taking in individual gamblers (Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002). We observed no group differences in sensation seeking, consistent with some (Blaszczynski et al. 1986; Parke et al. 2004; Ledgerwood et al. 2009) but not all (Cunningham-Williams et al. 2005) previous studies in PG. This may reflect the exclusively male sample (Nower et al. 2004), or it is possible that sensation seeking can be decomposed further into subfactors, such as boredom proneness, some of which may be associated with PG (Fortune & Goodie, 2010). Alternatively, sensation seeking may dispose recreational engagement with gambling rather than the transition to disordered gambling, and may therefore have less relevance to adult treatment-seeking groups (cf. van Leeuwen et al. 2010).

Finally, there were significant differences in delay discounting between the two groups, in addition to the individual differences seen on this measure. Both groups showed the standard ‘magnitude effect’ on the discounting task, such that large rewards of a relatively higher value (£75–£85) were discounted less than large rewards of a relatively smaller value (£25–£35). This is a consistent finding in the behavioural economics literature (Chapman, 1996; Green & Myerson, 2004), and, as in the original study using this measure in heroin addicts (Kirby et al. 1999), the magnitude effect did not interact with group status: participants with PG showed similar sensitivity to reward magnitude to the controls. Steeper discounting on the Kirby MCQ procedure replicates previous work in PG using other variants of the delay discounting paradigm (Petry, 2001a; Alessi & Petry, 2003; Dixon et al. 2003; MacKillop et al. 2006; Ledgerwood et al. 2009), and patients with Parkinson's disease with medication-induced PG also show steeper delay discounting than controls with Parkinson's disease on the MCQ (Housden et al. 2010). The discount rates in the PG group were correlated significantly with the UPPS-P subscales of ‘narrow’ impulsivity. This is in keeping with past personality studies in the general population, which primarily find an association with the Barratt non-planning subscale (Kirby et al. 1999; Mobini et al. 2007; Koff & Lucas, 2011). Although statistically significant in the larger studies, it is likely that this state–trait relationship is of only modest strength (r≈0.3) because of the distinct sources of variability in the two measures: one is an introspective evaluation of generalized impulsive tendencies and the other is a state measure involving a series of financial decisions.

Some limitations should be noted. First, the present sample was composed of only treatment-seeking PG, and findings may not generalize to all levels of disordered gambling (although see MacKillop et al. 2006), and our convenience sample included a mixture of cases tested before, during and after treatment. It was reported previously that ratings of gambling distortions are reduced by a course of psychotherapy (Breen et al. 2001), although such an effect was not statistically significant in our data, possibly because the CBT programme did not place a strong emphasis on the correction of specific gambling distortions. Nonetheless, the association with delay discounting remained highly significant when partialling for stage of treatment. Second, in this restricted sample we did not exclude participants with some of the common clinical co-morbidities with PG, including mood disorders and substance use disorders, which may be associated with impulsivity and discounting tendencies (Reynolds, 2006; Takahashi et al. 2008; Dombrovski et al. 2011). We note that the rate of substance use disorder co-morbidity was relatively low compared to international data in treatment-seeking PG (Ramirez et al. 1983; Black & Moyer, 1998), and we did not examine the additive impact of these co-morbidities on psychological functioning (e.g. Petry, 2001a) for reasons of statistical power.

Previous studies have described associations between facets of impulsivity and gambling severity (Steel & Blaszczynski, 1998; Krueger et al. 2005), physiological arousal during gambling (Anderson & Brown, 1984; Krueger et al. 2005), and short-term treatment outcomes (Leblond et al. 2003; Goudriaan et al. 2008). The present work highlights mood-related impulsivity (‘urgency’) and delay discounting as especially relevant facets in gambling behaviour. The correlation between delay discounting and gambling distortions may indeed shed further light on the nature of these faulty cognitions in disordered gambling. Previous work eliciting gambling distortions with the ‘think aloud’ technique has reported high rates of erroneous verbalizations even in non-problematic regular players (Ladouceur & Walker, 1996; Delfabbro, 2004), and it was not until psychometric measures such as the GRCS and GBQ were developed that the elevated level of distortions in PG became evident (Raylu & Oei, 2004a; Emond & Marmurek, 2010; Myrseth et al. 2010). However, it remains unclear from the psychometric scales whether increased scores reflect the frequency of these cognitions, the conviction with which the beliefs are held, or the tendency to use these beliefs to justify excessive gambling (Ladouceur & Walker, 1996; Delfabbro, 2004). Measures of impulsivity, and the delay discounting paradigm most specifically, capture the conflict between short-term gratification and longer-term gains. The resolution of these inter-temporal decisions recruits neural regions, including the ventral striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (McClure et al. 2004; Hariri et al. 2006; Sellitto et al. 2010), that are implicated in the pathophysiology of problem gambling (Potenza et al. 2003; Reuter et al. 2005; Lawrence et al. 2009b). These dilemmas may be analogous to the conflict that gamblers experience between the rapid acceptance of a distorted belief, versus a more deliberative, analytical appraisal that their recent gambling results do not reflect skill, luck or other common biases. Measures of impulsivity including delay discounting were also seen to predict more general Beckian cognitive distortions associated with psychopathology in a student sample (Mobini et al. 2006, 2007). Therefore, based on the link between delay discounting and GRCS scores, we hypothesize that the willingness to accept distorted gambling thoughts over more rational explanations may be a key pathological process in disordered gambling.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Medical Research Council (MRC) grant (G0802725) and completed within the Behavioural and Clinical Neuroscience Institute, supported by a consortium award from the MRC and Wellcome Trust (director: T. W. Robbins). A.V.-G. was funded by the grant Jose Castillejo (JC 2009-00265) from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science hosted by the Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Cambridge. Preliminary findings were presented at the National Centre for Responsible Gaming annual meeting (Las Vegas, November 2010) and the Society for the Study of Addiction annual meeting (York, UK, November 2010).

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Alessi SM, Petry NM. Pathological gambling severity is associated with impulsivity in a delay discounting procedure. Behavioral Processes. 2003;64:345–354. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(03)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G, Brown RI. Real and laboratory gambling, sensation-seeking and arousal. British Journal of Psychology. 1984;75:401–410. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1984.tb01910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Selby EA, Fink EL, Joiner TE. The multifaceted role of distress tolerance in dysregulated eating behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:718–726. doi: 10.1002/eat.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: delay discounting processes. Addiction. 2001;96:73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J, Gay P, Rochat L, Van Der Linden M. The role of urgency and its underlying psychological mechanisms in problematic behaviours. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:1085–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J, Van Der Linden M, Ceschi G. Which dimensions of impulsivity are related to cigarette craving? Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1189–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DW, Moyer T. Clinical features and psychiatric comorbidity of subjects with pathological gambling behavior. Psychiatric Services. 1998;49:1434–1439. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.11.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczynski A, Nower L. A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction. 2002;97:487–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczynski A, Steel Z, McConaghy N. Impulsivity in pathological gambling: the antisocial impulsivist. Addiction. 1997;92:75–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczynski AP, Wilson AC, McConaghy N. Sensation seeking and pathological gambling. British Journal of Addiction. 1986;81:113–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden-Jones H, Clark L. Pathological gambling: a neurobiological and clinical update. British Journal of Psychiatry. in press doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.088146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen RB, Kruedelbach NG, Walker HI. Cognitive changes in pathological gamblers following a 28-day inpatient program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:246–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman GB. Temporal discounting and utility for health and money. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition. 1996;22:771–791. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.22.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L. Decision-making during gambling: an integration of cognitive and psychobiological approaches. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 2010;365:319–330. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Lawrence AJ, Astley-Jones F, Gray N. Gambling near-misses enhance motivation to gamble and recruit win-related brain circuitry. Neuron. 2009;61:481–490. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins LF, Nadorff MR, Kelly AE. Winning and positive affect can lead to reckless gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:287–294. doi: 10.1037/a0014783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham-Williams RM, Grucza RA, Cottler LB, Womack SB, Books SJ, Przybeck TR, Spitznagel EL, Cloninger CR. Prevalence and predictors of pathological gambling: results from the St. Louis Personality, Health and Lifestyle (SLPHL) study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2005;39:377–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA Smith GT 2008aClarifying the role of personality dispositions in risk for increased gambling behavior Personality and Individual Differences 45503–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA Smith GT 2008bEmotion-based dispositions to rash action: positive and negative urgency Psychological Bulletin 134807–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Zapolski TC, Combs JL, Settles RF, Fillmore MT, Smith GT. Experimental effect of positive urgency on negative outcomes from risk taking and on increased alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:367–375. doi: 10.1037/a0019494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfabbro P. The stubborn logic of regular gamblers: obstacles and dilemmas in cognitive gambling research. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2004;20:1–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOGS.0000016701.17146.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Marley J, Jacobs EA. Delay discounting by pathological gamblers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:449–458. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrovski AY, Szanto K, Siegle GJ, Wallace ML, Forman SD, Sahakian B, Reynolds CF 3rd, Clark L. Lethal forethought: delayed reward discounting differentiates high- and low-lethality suicide attempts in old age. Biological Psychiatry 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.025. . Published online: 18 February 2011. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emond MS, Marmurek HH. Gambling related cognitions mediate the association between thinking style and problem gambling severity. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2010;26:257–267. doi: 10.1007/s10899-009-9164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1999;146:348–361. doi: 10.1007/pl00005481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris J, Wynne H. Canadian Problem Gambling Index. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse; Ottawa, Ontario: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fortune EE, Goodie AS. The relationship between pathological gambling and sensation seeking: the role of subscale scores. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2010;26:331–346. doi: 10.1007/s10899-009-9162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frascella J, Potenza MN, Brown LL, Childress AR. Shared brain vulnerabilities open the way for nonsubstance addictions: carving addiction at a new joint? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1187:294–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudriaan AE, Oosterlaan J, De Beurs E, Van Den Brink W. The role of self-reported impulsivity and reward sensitivity versus neurocognitive measures of disinhibition and decision-making in the prediction of relapse in pathological gamblers. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:41–50. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J. A discounting framework for choice with delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:769–792. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Brown SM, Williamson DE, Flory JD, De Wit H, Manuck SB. Preference for immediate over delayed rewards is associated with magnitude of ventral striatal activity. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:13213–13217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3446-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housden CR, O'Sullivan SS, Joyce EM, Lees AJ, Roiser JP. Intact reward learning but elevated delay discounting in Parkinson's disease patients with impulsive-compulsive spectrum behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2155–2164. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs D. A general theory of addictions: a new theoretical model. Journal of Gambling Behaviour. 1986;2:15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1999;128:78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koff E, Lucas M. Mood moderates the relationship between impulsiveness and delay discounting. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;50:1018–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger TH, Schedlowski M, Meyer G. Cortisol and heart rate measures during casino gambling in relation to impulsivity. Neuropsychobiology. 2005;52:206–211. doi: 10.1159/000089004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladouceur R, Walker M. Salkovskis P. M. Trends in Cognitive and Behavioural Therapies. Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 1996. A cognitive perspective on gambling; p. 89. ), pp. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AJ Luty J Bogdan NA Sahakian BJ Clark L 2009aImpulsivity and response inhibition in alcohol dependence and problem gambling Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 207163–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AJ Luty J Bogdan NA Sahakian BJ Clark L 2009bProblem gamblers share deficits in impulsive decision-making with alcohol-dependent individuals Addiction 1041006–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblond J, Ladouceur R, Blaszczynski A. Which pathological gamblers will complete treatment? British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;42:205–209. doi: 10.1348/014466503321903607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood DM, Alessi SM, Phoenix N, Petry NM. Behavioral assessment of impulsivity in pathological gamblers with and without substance use disorder histories versus healthy controls. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;105:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur HR, Blume SB. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): a new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:1184–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J, Doll H, Hawton K, Dutton WH, Geddes JR, Goodwin GM, Rogers RD. How psychological symptoms relate to different motivations for gambling: an online study of internet gamblers. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Anderson EJ, Castelda BA, Mattson RE, Donovick PJ. Convergent validity of measures of cognitive distortions, impulsivity, and time perspective with pathological gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:75–79. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure SM, Laibson DI, Loewenstein G, Cohen JD. Separate neural systems value immediate and delayed monetary rewards. Science. 2004;306:503–507. doi: 10.1126/science.1100907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NV, Currie SR. A Canadian population level analysis of the roles of irrational gambling cognitions and risky gambling practices as correlates of gambling intensity and pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2008;24:257–274. doi: 10.1007/s10899-008-9089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitzner GB, Whelan JP, Meyers AW. Comments from the trenches: proposed changes to the DSM-V classification of pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9225-x. . Published online: 24 October 2010. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobini S, Grant A, Kass AE, Yeomans MR. Relationships between functional and dysfunctional impulsivity, delay discounting and cognitive distortions. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:1517–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Mobini S, Pearce M, Grant A, Mills J, Yeomans MR. The relationship between impulsivity, sensation seeking and cognitive distortions in a sample of non-clinical population. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40:1153–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L, Warusawitharana M. Area under the curve as a measure of discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2001;76:235–243. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2001.76-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrseth H, Brunborg GS, Eidem M. Differences in cognitive distortions between pathological and non-pathological gamblers with preferences for chance or skill games. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2010;26:561–569. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson HE, Willison J. National Adult Reading Test (NART) Test Manual. NFER-Nelson; Windsor, UK: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nower L, Derevensky JL, Gupta R. The relationship of impulsivity, sensation seeking, coping, and substance use in youth gamblers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:49–55. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oei TP, Gordon LM. Psychosocial factors related to gambling abstinence and relapse in members of Gamblers Anonymous. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2008;24:91. doi: 10.1007/s10899-007-9071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke A, Griffiths M, Irwing P. Personality traits in pathological gambling: sensation seeking, deferment of gratification and competitiveness as risk factors. Addiction Research and Theory. 2004;12:201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM 2001aPathological gamblers, with and without substance use disorders, discount delayed rewards at high rates Journal of Abnormal Psychology 110482–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM 2001bSubstance abuse, pathological gambling, and impulsiveness Drug and Alcohol Dependence 6329–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101:142–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01591.x. (Suppl. 1), [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN, Leung HC, Blumberg HP, Peterson BS, Fulbright RK, Lacadie CM, Skudlarski P, Gore JC. An FMRI Stroop task study of ventromedial prefrontal cortical function in pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1990–1994. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez LF, McCormick RA, Russo AM, Taber JI. Patterns of substance abuse in pathological gamblers undergoing treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1983;8:425–428. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(83)90044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raylu N Oei TP 2004aThe Gambling Related Cognitions Scale (GRCS): development, confirmatory factor validation and psychometric properties Addiction 99757–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raylu N Oei TP 2004bRole of culture in gambling and problem gambling Clinical Psychology Review 231087–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter J, Raedler T, Rose M, Hand I, Glascher J, Buchel C. Pathological gambling is linked to reduced activation of the mesolimbic reward system. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:147–148. doi: 10.1038/nn1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B. A review of delay-discounting research with humans: relations to drug use and gambling. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2006;17:651–667. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280115f99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellitto M, Ciaramelli E, Di Pellegrino G. Myopic discounting of future rewards after medial orbitofrontal damage in humans. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:16429–16436. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2516-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer HJ, Labrie R, Scanlan KM, Cummings TN. Pathological gambling among adolescents: Massachusetts Gambling Screen (MAGS) Journal of Gambling Studies. 1994;10:339–362. doi: 10.1007/BF02104901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe L. A reformulated cognitive-behavioral model of problem gambling. A biopsychosocial perspective. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:1–25. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. (Suppl. 20), ; quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Poulton R. Personality and problem gambling: a prospective study of a birth cohort of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:769–775. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z, Blaszczynski A. Impulsivity, personality disorders and pathological gambling severity. Addiction. 1998;93:895–905. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93689511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergh TA, Meyers AW, May RK, Whelan JP. Development and validation of the Gamblers' Beliefs Questionnaire. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Oono H, Inoue T, Boku S, Kako Y, Kitaichi Y, Kusumi I, Masui T, Nakagawa S, Suzuki K, Tanaka T, Koyama T, Radford MH. Depressive patients are more impulsive and inconsistent in intertemporal choice behavior for monetary gain and loss than healthy subjects – an analysis based on Tsallis' statistics. Neuroendocrinology Letters. 2008;29:351–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toneatto T, Blitz-Miller T, Calderwood K, Dragonetti R, Tsanos A. Cognitive distortions in heavy gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies. 1997;13:253–266. doi: 10.1023/a:1024983300428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen AP, Creemers HE, Verhulst FC, Ormel J, Huizink AC. Are adolescents gambling with cannabis use? A longitudinal study of impulsivity measures and adolescent substance use: the TRAILS study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;72:70–88. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-Garcia A, Lawrence AJ, Clark L. Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance-use disorders: review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers and genetic association studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32:777–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Arseneault L, Tremblay RE. Impulsivity predicts problem gambling in low SES adolescent males. Addiction. 1999;94:565–575. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94456511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle H, Moody A, Spence S, Orford J, Volberg R, Jotangia D, Griffiths M, Hussey D, Dobbie F. British Gambling Prevalence Survey. National Centre for Social Research; London: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Xian H, Shah KR, Phillips SM, Scherrer JF, Volberg R, Eisen SA. Association of cognitive distortions with problem and pathological gambling in adult male twins. Psychiatry Research. 2008;160:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]