1. Introduction

Proliferation is driven by an intricate machinery, the smooth operation of which is essential for the development and survival of the organism. The central task of this machinery is to copy the genetic material of a dividing cell and to distribute it evenly between daughter cells. Yet, in higher eukaryotes, the division of every single cell has to be coordinated with the development of the whole organism. Mistakes in this cell cycle program are rarely tolerated: they give rise to developmental aberrations or cancer and often lead to the organism's demise.

A collaborative effort from many laboratories has transformed our understanding of the cell cycle from a black box to an amazing level of molecular detail. Early groundbreaking studies revealed the crucial role of oscillating kinase activities in driving the embryonic cell cycle1–4. The activation of a kinase, which was first referred to as "maturation-promoting factor" and later identified to be cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk1, was shown to trigger entry of cells into mitosis. Its capability to phosphorylate its substrates is dependent on the periodic synthesis of essential cyclin subunits5–7. Consequently, the removal of cyclins shuts down Cdk1 and leads to exit from mitosis. It was soon realized that ]cyclins are disposed of by ubiquitin-proteasome dependent degradation8, which brought ubiquitination into the limelight of cell cycle control.

Subsequent studies extended the role of ubiquitination in regulating proliferation far beyond its part in the tug-of-war between kinase-activation and protein degradation. Ubiquitination also regulates checkpoints that ensure the high fidelity of cell division, and signaling networks that couple proliferation to differentiation and development. Such a powerful role in cell cycle control comes with its own risk, and many malignancies result from aberrant ubiquitination. In this review, we will discuss key concepts which illustrate how ubiquitination regulates cell cycle progression, and how its misregulation can trigger aberrant proliferation and cancer.

2. The players in ubiquitin-dependent cell cycle control

2.1 An enzymatic cascade mediates ubiquitin-dependent cell cycle control

During ubiquitination, a covalent isopeptide bond is formed between the carboxy-terminus (C-terminus) of ubiquitin and a nucleophilic side chain in the substrate protein9,10. In the vast majority of cases, ubiquitin is linked to the ε-amino group of lysine residues, but modifications also occur at the amino-terminus11, the hydroxyl-group of serine residues12, or the thiol-group of cysteine residues13,14.

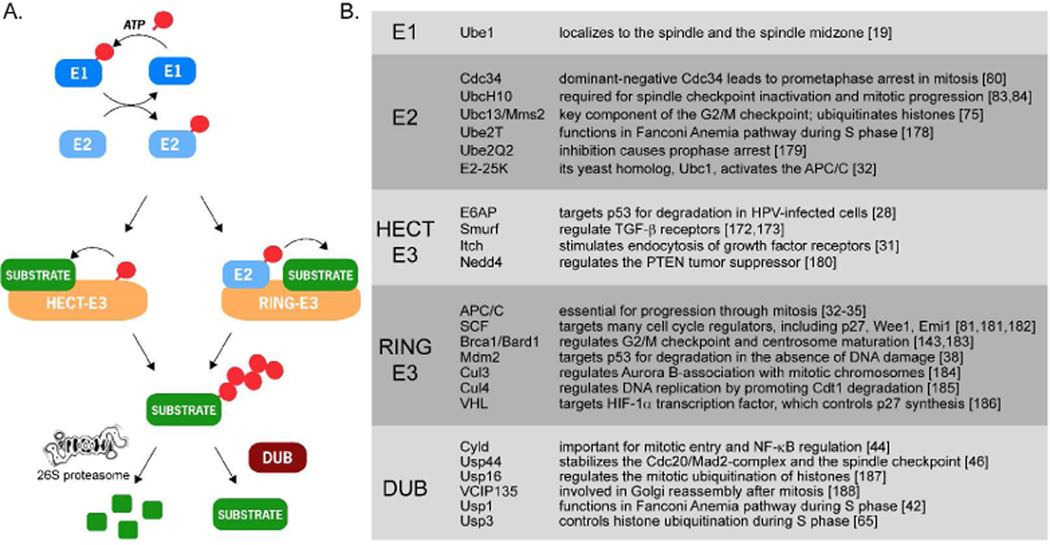

In order to allow the transfer of ubiquitin to its acceptor, it is first activated by a ubiquitin-activating enzyme, E1 (Fig. 1). E1 uses ATP to form a phosphodiester bond between the C-terminus of ubiquitin and AMP, before the ubiquitin is transferred to the active-site cysteine of E1 by thioester formation15. At least two human E1 enzymes activate ubiquitin16–18, but in most cases, this reaction is carried out by the product of the essential UBE1 gene. In dividing cells, the Ube1 protein localizes to hotspots of cell cycle control, such as the cytoskeleton, the mitotic spindle, or the spindle midzone19. Cell lines carrying thermosensitive mutations in UBE1 suffer from cell cycle arrest, and in fact provided early evidence that ubiquitination is crucial for cell cycle control20.

Figure 1. Enzymatic players in ubiquitin dependent cell cycle control.

A. Schematic overview over the enzymatic cascade catalyzing ubiquitination. B. Examples of enzymes at the different steps of ubiquitination that have roles in ubiquitin-dependent cell cycle control.

The charging with ubiquitin triggers conformational changes in E1 that expose a binding site for the recruitment of one of ~60 human ubiquitin conjugating enzymes, or E2s21. E2s receive the activated ubiquitin on an active-site cysteine by trans-esterification. Most E2s are single domain proteins, some of which have short extensions at the N- or C-terminus. Several of these E2s, including Ubc13, Cdc34, or UbcH10, have central functions in cell cycle control. In few cases, E2 domains are found in large multifunctional proteins, one of which, the 528 kDa BRUCE, localizes to the spindle midzone and functions during the abscission stage of cytokinesis22.

Once ubiquitin is bound to an E2, its transfer to the substrate relies on ubiquitin-protein ligases, or E3s. The E3s recruit distinct sets of substrates and thereby provide most of the specificity of ubiquitination. They largely come in two different flavors, and either contain a catalytic HECT- or RING-domain. HECT-domains (Homologous to E6AP C-Terminus) harbor an active-site cysteine, which is charged with ubiquitin by E2s before the ubiquitin is transferred to the substrate. By contrast, RING-E3s (Really Interesting New Gene) do not have an active site cysteine. Instead, they bind at the same time to the charged E2 and the substrate, and activate the E2 to transfer ubiquitin directly to the substrate acceptor23–26.

With ~50 HECT- and ~600–1000 RING-domain containing proteins, E3s are the most abundant class of ubiquitination enzymes in humans. Many of these enzymes have pivotal roles in cell cycle control. For example, HECT-E3s are named after the E6AP protein, which is hijacked by the human papillomavirus E6 protein to catalyze the ubiquitination and degradation of the cell cycle regulator p5327, 28. Other HECT-E3s implicated in cell cycle control include Smurf ubiquitin ligases that terminate anti-mitogenic TGF-β signaling29,30, or Itch, which promotes the endocytosis of ErbB4 growth factor receptors31. Among the many RING-E3s controlling proliferation are the anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C)32–35, the SCF36, the tumor suppressor Brca1/Bard137, or the oncogene Mdm238.

The modification with ubiquitin can be reversed by ~100 human deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs)39,40. DUBs contain a cysteine protease domain or a Zn2+-binding JAMM domain41, through which they hydrolyze the isopeptide bond between the C-terminus of ubiquitin and the substrate. As regulators of proliferation, DUBs themselves are controlled during cell cycle progression by recruitment of binding partners42, regulation of expression levels43,44, autocatalytic cleavage45, or modifications46. The misregulation of DUBs can result in aberrant proliferation and cancer, which is well understood for the tumor suppressor Cyld44,47.

Proteins decorated with ubiquitin chains containing at least four ubiquitin molecules can be recognized by the 26S proteasome48. The proteasome is a compartmentalized protease, which unfolds ubiquitinated proteins and degrades them in a secluded chamber49. It recognizes ubiquitinated proteins by using dedicated receptors, which either bind the proteasome transiently or are integral components of the proteasomal cap49–51. Before substrates are degraded, ubiquitin is cleaved off by proteasome-resident DUBs, so that it can be reused by the cell40. The activities of the proteasome and its associated DUBs are essential for cell cycle progression. Consequently, proteasome inhibition blocks proliferation of cancer cells, and has recently been approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma52.

2.2 The APC/C and the SCF: leading characters in the cell cycle cast

Two main characters in this impressive cast of enzymes are the anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C) and the SCF32–36. Both enzymes are essential for proliferation in all eukaryotes. In dividing cells, the APC/C orchestrates progression through mitosis and G1, while the SCF operates at all stages of the cell cycle program. Despite differences in their temporal regulation, the APC/C and the SCF are very similar in their basic architecture.

Both the APC/C and the SCF are oligomeric RING-E3s, which have multiple core subunits (4 in the case of SCF; 13 for APC/C)53. In both enzymes the catalytic activity is provided by RING-finger proteins, Rbx1 or Ro52 in SCF36,54 and Apc11 in APC/C55, which are anchored to the enzyme by a scaffold cullin protein (Cul1 in SCF and Apc2 in APC/C). The various substrates are delivered to the SCF or APC/C by specific adaptors that associate only transiently with the E3s. The SCF, for example, uses ~60 F-box proteins, which contain an F-box domain to associate with the SCF-core subunit Skp1, and a substrate binding domain, such as WD40- or leucine-rich repeats56. The equivalent of F-box proteins in the APC/C are the co-activators Cdc20 and Cdh1, which employ WD40-repeats as substrate binding domains57,58.

While the blueprints for SCF and APC/C are similar, differences exist in the regulation of substrate-binding to these E3s. The SCF is always eager to promote ubiquitination, but only modifies substrates that have been marked by posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation or hydroxylation. Once a substrate is phosphorylated, it is rapidly recognized by the F-box protein and delivered for ubiquitination to the SCF36. Mutation of phosphorylation sites or kinases stabilizes SCF-substrates, which in the case of β-catenin results in aberrant cell cycle control and cancer59. Contrary to SCF, the activity of the APC/C itself is regulated during the cell cycle, and APC/C-substrates are usually not modified. The APC/C is activated during mitosis by phosphorylation of core subunits60, and it is shut down during late G1 by degradation of its specific E2 UbcH1061, degradation and inhibitory phosphorylation of the substrate targeting factors Cdc20/Cdh157, and expression of its inhibitor Emi157,63. Additional inhibitors, such the spindle checkpoint proteins Mad2 and BubR1, ensure APC/C-activation at the proper time and place during the cell cycle, which will be discussed in more detail throughout this review62–64.

2.3 Different ubiquitin modifications have distinct functions in cell cycle control

The intimate collaboration of E1, E2s, and E3s results in the transfer of a single ubiquitin (monoubiquitination) or the decoration of substrates with ubiquitin chains (multiubiquitination) (Fig. 2). Depending on the modified protein, monoubiquitination recruits different partners that then trigger specific reactions. In eukaryotic cell cycle control, the monoubiquitination of histones is important for recognition of stalled replication forks and S phase progression65,66; monoubiquitination of growth factor receptors regulates their endocytosis and limits growth factor signaling67; and monoubiquitination of PCNA recruits translesion polymerases to mediate DNA repair, thereby removing road-blocks to cell cycle progression68.

Figure 2. Different ubiquitin modifications have distinct functions in cell cycle control.

Substrates can be modified with a single ubiquitin (monoubiquitination) or with ubiquitin chains (multiubiquitination). Ubiquitin chains differ in structure and function, depending on what lysine of ubiquitin is used for chain formation. Examples for different modifications and their substrates in cell cycle control are shown on the right.

When chains are assembled, one of the seven lysine residues of ubiquitin serves as acceptor site for the next ubiquitin to be attached. Depending on the lysine residue preferentially employed for chain formation, these chains differ in structure and function69,70. In yeast, all lysine residues of ubiquitin can be modified71, but we understand most about the consequences of chains linked through K48, K11, or K63. K48-linked chains are bound by the 26S proteasome; they are the canonical signal for degradation, and essential for proliferation32. Chains linked through K11 of ubiquitin are assembled by the human cell cycle E3 anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C)72,73. These K11-linked chains are recognized by several proteasomal substrate receptors and trigger the degradation of APC/C-substrates. As the APC/C is required for proliferation in all eukaryotes, it is likely that K11-linked chains are essential, too, but this remains to be determined. By contrast, K63-linked ubiquitin chains usually function independently of the 26S proteasome. By recruiting specific binding partners to modified substrates, K63-linked chains activate kinases during inflammation74, orchestrate events in the G2/M-checkpoint75, or mediate lysosomal targeting of activated growth factor receptor76.

What determines which chain type is formed? In many cases, the ubiquitin chain topology is dependent on the E2. K63-linked chains, for example, are assembled by the heterodimeric E2, Mms2-Ubc13, which functions in cell cycle control due to its role in the G2/M-checkpoint. Mms2, a ubiquitin-E2 variant (UEV), has no E2-activity itself. Instead, it binds the acceptor ubiquitin, which brings K63 of the acceptor ubiquitin into proximity of the active site of the E2 Ubc1377. Since Ubc13 can only function when presented with an acceptor ubiquitin by Mms2, Mms2-Ubc13 is able to elongate ubiquitin chains, but may be unable to add the first ubiquitin to a substrate lysine78,79.

In a similar manner, E2s are pivotal for the formation of K48- and K11-linked chains32,72,80. The E2 Cdc34, which is important at multiple cell cycle stages80,81, is responsible for the assembly of K48-linked chains by the cell cycle E3 SCF. This capability of Cdc34 requires a conserved acidic loop in Cdc34, which may directly contact ubiquitin82. Also, the formation of K11-linked chains by the APC/C depends on its E2, UbcH10, which is required for progression of cells beyond metaphase72,73,83,84. The assembly of K11-linked chains by APC/C and UbcH10 relies on short sequence motifs present in substrates and in ubiquitin, which are referred to as TEK-boxes72. In addition, UbcH10 cooperates with a novel E2-activating enzyme, which helps determine the specificity for K11-linked ubiquitin chains (KEW, AW, unpublished).

3. The different functions of ubiquitination in cell cycle control

Ubiquitin is such a crucial regulator of proliferation that discussing every mechanism of ubiquitin-dependent cell cycle control would go far beyond the scope of this review. We will instead focus our discussion on selected examples that illustrate how ubiquitin can take charge over proliferation. We will review how ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis ensures the regulated and unidirectional progression through the cell cycle; how ubiquitination and proteolysis orchestrate the function of cell cycle checkpoints; and how ubiquitination and endocytosis coordinate proliferation with development.

3.1 The role of ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis in cell cycle progression

3.1.1 Don't look back: generation of irreversible cell cycle transitions

Cells have to guarantee that their genomic information is replicated only once per cell cycle and that the two identical copies are distributed evenly between the daughter cells. To this end, cells have to ensure that replication always precedes mitosis. The necessary unidirectionality of cell cycle progression depends on irreversible transitions between cell cycle stages, which is achieved by ubiquitin-dependent degradation.

A well characterized example of how ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis generates irreversible cell cycle transitions is exit from mitosis, which depends on the degradation of cyclin proteins8. The A- and B-type cyclins activate the major mitotic kinase, Cdk1, to constitute "maturation promoting factor", the activity of which is required for establishing and maintaining the mitotic state. Without cyclins, Cdk1 is unable to bind and phosphorylate its many mitotic substrates5. Consequently, the ubiquitination of cyclins A and B by the anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C) and their degradation by the 26S proteasome efficiently shuts down Cdk1 and promotes exit from mitosis. The importance of this proteolytic event is illustrated by cells that fail to degrade cyclins: they arrest in mitosis. Such failure of cyclin degradation can be caused by inhibition of the proteasome85, activation of checkpoints that inhibit the APC/C62, or expression of cyclin-mutants not recognized by the APC/C86.

The degradation of cyclins is the key mechanism of triggering Cdk1-inactivation and mitotic exit in eukaryotes. To test whether the irreversibility of mitotic exit relies on ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis, mitotic cells can be treated with the Cdk1-inhibitor flavopiridol87. As active Cdk1 is essential for mitosis, its inhibition by flavopiridol promotes mitotic exit, and this occurs even if the degradation of cyclin B is blocked by proteasome inhibitors87. If flavopiridol is removed from postmitotic cells still containing cyclin B1, however, the remaining cyclin quickly activates Cdk1 and pushes cells back into mitosis! Upon reverse entry into mitosis, cells break down their nuclear envelopes, condense their chromosomes, and align them at the metaphase plate. If occurring during normal cell cycle progression, such a "reverse transition" would wreak havoc as mitotic checkpoints will not be fully functional and the likelihood of mistakes in chromosome segregation will be high. Since in the absence of drugs, mitotic exit depends on cyclin B1 degradation, such inappropriate reverse transitions cannot occur. Thus, ubiquitin-dependent degradation is essential for the irreversible nature of the M-G1 transition.

Ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis serves a similar role in establishing the irreversible transition from G1 into S, which is pivotal for DNA replication88. During G1, when Cdk-activity is low, cells license their origins of replication. However, they initiate DNA replication only after having activated cyclin-dependent kinases at the G1-S transition. Irreversible kinase activation is brought about, at least in part, by the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of a Cdk-inhibitor, p27. If degradation of p27 is disturbed, cells can revert back from S into G1, and re-license origins of replication again that have already been used. This allows these cells to amplify genes or chromosomes, an event often observed in tumors89,90.

Consistent with its importance for cell cycle control, the degradation of p27 is tightly regulated. When, during G1, cells commit to another round of cell division, they activate Src and Abl kinases. These kinases phosphorylate p27 on a conserved tyrosine, Y88, which leads to the displacement of p27 from its binding site in the catalytic cleft of Cdk291,92. This in turn allows cyclin E/Cdk2 to phosphorylate p27 on another conserved threonine, T187, thereby creating a binding site for p27 on the F-box protein Skp2 and its associate Cks181. Together with Cks1, SCFSkp2 ubiquitinates p27 and marks the Cdk-inhibitor for degradation by the 26S proteasome, which results in a burst of Cdk2-activity, activation of E2F transcription factors, and synthesis of more A- and E-type cyclins93. The ensuing full activation of Cdk2 commits cells to entry into S. Since no p27 is left, cells cannot revert back into G1, and entry into S is irreversible.

The degradation of p27 provides directionality, but also releases a brake in the cell cycle, which is exploited by hyperproliferative tumor cells. For example, amplification of the EGF receptor in breast cancer cells, or activation of Abl by the BCR-ABL translocation in chronic myelogenous leukemia, activates Src or Abl kinases and targets p27 for degradation88,94. Loss of the PTEN tumor suppressor results in increased expression of Skp2, and conversely, lower levels of p2795. Overexpression of Skp2 is, in fact, observed in many malignancies96. An increased level of p27 degradation is a prognostic factor for disease progression and therapeutic response in cancer, with low levels of p27 correlating with poor prognosis.

3.1.2 Step by step: transitions within a cell cycle stage

Not only transitions between cell cycle stages, but also the processes within one cell cycle phase have to occur in a defined sequence. This is illustrated during mitosis, which in mammalian cells takes less than one hour. In this short period of time, cells break down their nuclear envelope, condense their chromosomes, attach them to the spindle, distribute the sister chromatids to the two daughter cells, and finally, separate the daughters during cytokinesis. Just imagine a cell starting cytokinesis before the chromosomes were even attached to the spindle - big mistake!

The sequence of mitotic events is determined by closely connected processes, including phosphorylation of hundreds of proteins and precisely timed ubiquitin-dependent degradation. The main director of mitotic degradation is the APC/C, which in addition to the cyclins mentioned before, controls the turnover of other mitotic kinases, spindle organizers, centrosomal proteins, kinesins, cytokinesis regulators, and finally, of its own E2, UbcH1053,57,61,97,98. The APC/C ubiquitinates its substrates in a sequential manner, referred to as "substrate ordering"72,99. As much as we can tell from the analysis of APC/C-substrates in multiple species, the sequence of APC/C-dependent ubiquitination reactions is conserved through evolution100,101. Disturbing substrate ordering would be deleterious: for example, the premature degradation of the cytokinesis regulator Plk1 can lead to massive cytokinesis defects and multinucleation97.

Consistent with the robustness of cell cycle control, several mechanisms keep up substrate ordering by the APC/C. Anything but an unbiased enzyme, the APC/C discriminates between substrates by catalyzing their ubiquitination with different degrees of processivity99,102. Its "favorites", such as cyclin B1 or securin, are decorated with long ubiquitin chains within a single binding event. The length of the ubiquitin chains attached to such processive substrates exceeds the four ubiquitin molecules required for recognition by the proteasome48. The most processive substrates of the APC/C are consequently the first proteins to be degraded after the APC/C is switched on to fully active at the metaphase-anaphase transition.

Less preferred substrates, however, require multiple binding events to the APC/C to receive a ubiquitin chain long enough for proteasomal recognition. After dissociation, these distributive, partially ubiquitinated substrates compete for re-binding to the APC/C with all its other substrates. The competitiveness of the mitotic environment is illustrated by a comparison of protein concentrations: each of the rate-limiting APC/C-activators Cdc20 and Cdh1 is present at approximate concentrations of 50nM, while the combined concentration of all mitotic APC/C-substrates exceeds 2–3µM (MR, unpublished). A slight increase in the level of a processive substrate can throw the whole system off balance and bring mitotic progression to a halt103. The dissociated substrates are also recognized by deubiquitinating enzymes, which remove already attached ubiquitin46,99. Together, these mechanisms delay the degradation of distributive substrates to late mitosis or G1. With few exceptions discussed below, the degree of processivity of ubiquitination matches the timing of degradation of APC/C-substrates. Substrate ordering by the APC/C, therefore, is the outcome of a fierce competition between ubiquitination and deubiquitination, and thus, similar to a mechanism of kinetic proofreading proposed by Hopfield104.

The exceptions to the processivity rule are APC/C-substrates that are degraded earlier than expected from their processivity of ubiquitination. These substrates are all turned over when the bulk of the APC/C is inhibited by the mitotic spindle checkpoint. They include cyclin A, which activates Cdk1105; the mitotic kinase Nek2, which is important for centrosome separation106; and the CDK-inhibitor p21107. All of these substrates require Cdc20 for degradation, but the mechanisms allowing their degradation despite inhibition of Cdc20 by the spindle checkpoint are only beginning to be understood. It may involve direct binding of substrates to core APC/C-subunits, direct competition with spindle checkpoint components for binding to Cdc20, or alternative means of APC/C-targeting by Cdk1108,109.

A third mechanism contributing to the efficient degradation of mitotic APC/C-substrates is the co-localization of APC/C and substrates at cellular "hotspots". While much of the APC/C is found in the cytoplasm, it also accumulates on the centrosome and the spindle during mitosis110. APC/CCdc20 is activated by Cdk1-dependent phosphorylation, and APC/C-subunits phosphorylated on Cdk1-consensus sites are first detected on the spindle pole60. The activation of the APC/C on the centrosome or the spindle coincides with the localization of several substrates, including cyclin B1, Tpx2, or Aurora A, to these sites. In Drosophila, the APC/C-substrate cyclin B1 is first degraded on the centrosome, and only later on the spindle and in the cytoplasm111. Loosing the connection between the centrosome and the spindle, which occurs in "centrosome-fall-off"-mutant flies, allows degradation of cyclin B1 at the centrosome, but stabilizes it on the spindle112. Different mechanisms that target inactive APC/C to the spindle or to kinetochores have been proposed113,114, but how active APC/C is brought to microtubules remains to be determined. A recently identified E2-activating enzyme, which can bind both APC/C and microtubules, might provide the missing link (KEW, AW, unpublished).

3.1.3 Road-blocks to progress: generating a regulated cell cycle transition

Especially in higher eukaryotes, it is not only important that cell division occurs with high precision, but also that it is integrated into the development of the whole organism. The coordination of proliferation with development depends on signaling by growth and differentiation factors. In order to remain responsive for growth-factor signaling, cells have engineered road blocks against progression through the G1 phase, which depend on ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis brought about by well studied tumor suppressors.

One of the best understood examples is the human tumor suppressor Fbw7115. Fbw7 is an F-box protein that recognizes phosphorylated substrates and targets them for ubiquitination by the SCFFbw7 and degradation by the proteasome. Most of the substrates of Fbw7 have important roles in promoting the transition from G1 to S, and their degradation ensures that cells progress into S only after receiving the appropriate signals from their environment. Such Fbw7-substrates include cyclin E, which activates Cdk2 kinase to drive entry into S; the transcription factor c-myc, which promotes entry into S by increasing the synthesis of several cell cycle regulators; and the signaling molecule Notch, which plays a key role in development116–119. The recognition of substrates by Fbw7 requires their phosphorylation on two sites spaced by four amino acids. In most, if not all cases, the kinase responsible for phosphorylation at the −4 site is GSK3, which is regulated by mitogenic signaling118. If mitogenic signaling is low (i.e. the environment tells the cell not to divide), GSK3-activity is high. Consequently, Fbw7-substrates are fully phosphorylated, ubiquitinated, and degraded, and the cell has to await better conditions to proceed with its cell cycle program.

Loss of Fbw7 function allows cells to proliferate even under adverse conditions, as such encountered by rapidly dividing tumor cells. As this endows tumor cells with a growth advantage, Fbw7 function is often impaired in cancer115. This can occur by deletion of one allele or by mutations in the substrate-binding domain of Fbw7. Conversely, mutations in substrates can also block their phosphorylation or recognition by Fbw7, as observed with c-myc mutations in Burkitt's lymphoma115. Finally, the viral oncogene SV40 large T antigen (LT) possesses a Fbw7-recognition site, yet binding to Fbw7 does not result in SV40 LT-ubiquitination. By functioning as a pseudosubstrate, SV40 LT blocks the substrate-binding site on Fbw7 and stabilizes oncogenic Fbw7-substrates120. The inhibition of E3s by pseudosubstrates has recently emerged as a widespread regulatory mechanism of ubiquitin-dependent cell cycle control, providing a fine example of how studying viral oncogenes can shed light on normal proliferation control63,121.

3.1.4 The final transition: irreversible exit from the cell cycle

A final transition has to be established when cells exit their cell cycle program. This can occur reversibly during periods of starvation, or in stem cells that divide rarely and spend most of their time in a quiescent state. However, when cells are instructed to adopt a specific fate during terminal differentiation, they irreversibly cease to proliferate, and this process is dependent on ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis.

The differentiation of dividing stem cells into non-dividing, terminally differentiated cells requires tight transcriptional regulation, which is brought about by opposing transcriptional activators and repressors. The degradation of repressors allows cells to rapidly activate genes in response to differentiation cues. A point in case is made by the REST protein, which in stem cells represses the transcription of neuronal genes, such as ion channels or neurotransmitter receptors. Upon differentiation, REST is phosphorylated on C-terminal residues and subsequently recognized by the F-box protein βTrCP122–124. SCFβTrCP decorates REST with K48-linked ubiquitin chains and targets it for degradation, which coincides with the expression of neuron-specific genes. If this process is blocked, as observed pathologically by C-terminal frame-shift mutations interfering with REST-recognition by βTrCP125, neuronal differentiation is impaired. By retaining the stem cell character of neuronal precursor cells, stabilized REST behaves likes an oncogene, and indeed it is overexpressed in brain cancers123.

In addition to its function during neurogenesis, REST represses the transcription of the essential mitotic spindle checkpoint component Mad2124. In dividing cells, REST is ubiquitinated by SCFβTrCP and degraded by the 26S proteasome during G2. The degradation of REST is required for achieving expression levels of Mad2 high enough for the functionality of the spindle checkpoint. The stabilization of REST, or its overexpression observed in medullablastoma, compromises the spindle checkpoint and harbors the potential of introducing genetic instability. These consequences are reminiscent to deletion of one MAD2 allele, which predisposes mice to cancer development126. The degradation of REST, therefore, stands out as a spectacular example of the close connections between proliferation and differentiation, but also as an Achilles heel of stem cells: if REST is stabilized, stem cells do not efficiently differentiate, while at the same time, their ongoing proliferation has lost its precision.

Underscoring the importance of coordinating proliferation with development, the other major cell cycle E3, the APC/C, also functions during differentiation. In addition to orchestrating progression of cells through mitosis, APC/CCdh1 regulates synapses in Drosophila and C. elegans127,128, and controls axonal growth and patterning in the developing nervous system of mice129. Important APC/CCdh1-substrates in differentiating neurons are the SnoN and Id (inhibitors of differentiation) transcriptional repressors130–132. The degradation of these repressors activates the transcription of neuron-specific genes following cell cycle exit. APC/CCdh1 also stabilizes the G1 cell cycle stage, which is the time when cell cycle exit occurs during differentiation. Thus, APC/CCdh1 generates a cell cycle state conducive to differentiation, and then contributes to the establishment of a specific cellular fate, thereby elegantly coordinating proliferation with differentiation.

3.2 The role of ubiquitination in cell cycle checkpoints

The faithful execution of the cell cycle program is constantly monitored by checkpoint networks, which detect damage or the failure to complete a cell cycle stage. The activation of these checkpoints halts cell cycle progression, and provides cells with time to repair the damage. The importance of checkpoints for faithful cell division is underscored by their frequent loss of function in cancer. Ubiquitination plays key roles in checkpoint establishment, maintenance, and inactivation.

3.2.1 To control and to be controlled: ubiquitin and the spindle checkpoint

The complexity of ubiquitin-dependent checkpoint control is revealed during mitosis, when condensed chromosomes have to be attached to the spindle by kinetochore-microtubule interactions133. It is essential that the kinetochores of the two sister chromatids are connected to microtubules emanating from opposing spindle poles - otherwise both sister chromatids would end up in the same, then aneuploid daughter cell. Since sister chromatids are held together by a ring-shaped protein complex, cohesin, the correct bipolar spindle attachment of chromosomes generates tension between the sister chromatids. The lack of microtubule attachment at a single kinetochore or lack of tension between sister chromatids activates the spindle checkpoint58. The spindle checkpoint then inhibits the ubiquitin ligase APC/C, the activation of which would trigger sister chromatid separation by targeting inhibitors of the cohesin-protease, separase, for proteasomal degradation134. By inhibiting the APC/C, the spindle checkpoint allows cells to correct erroneous chromosome attachment before the sister chromatids are distributed to the daughter cells.

The direct target of the spindle checkpoint is the substrate-recruitment factor and APC/C-activator Cdc20. Cdc20 is sequestered in stoichiometric complexes with its inhibitors Mad2 and BubR162,64. The binding of Mad2 to Cdc20 occurs at unoccupied kinetochores. It involves a template mechanism, where one stably kinetochore-bound Mad2 (through interaction with another checkpoint component, Mad1) changes the conformation in another Mad2-molecule that is then capable of Cdc20-binding135,136. The resulting Cdc20-Mad2 complex resembles a "seatbelt"-conformation, which is very stable137. In addition, the yeast BubR1-homolog Mad3 binds and inhibits Cdc20 as an APC/C-pseudosubstrate121. The sequestration of Cdc20 in these complexes inactivates the APC/C and arrests cells at metaphase.

After all chromosomes have achieved bipolar attachment to the spindle, sister chromatid separation is rapidly initiated and occurs simultaneously throughout the cell. This indicates that the spindle checkpoint is inactivated in a switch-like manner, which is achieved, at least in part, by ubiquitination. Following the completion of chromosome attachment, the p31comet protein and the E2 UbcH10 catalyze the APC/C-dependent multiubiquitination of Cdc20 itself and potentially other proteins as well84,138. The APC/C-dependent multiubiquitination does not result in Cdc20 degradation, but instead triggers the dissociation of Cdc20 from its inhibitor Mad2, activation of APC/CCdc20, and initiation of sister chromatid separation. It is likely that ubiquitination causes conformational changes in Cdc20 leading to Mad2-release, or recruits a ubiquitin-selective segregase, such as p97Ufd1/Npl4, to disassemble the Cdc20/Mad2-complexes in an ATP-dependent manner139,140. Following its activation, the APC/C promotes the degradation of cyclin B1, Mps1, and Bub1, which are all required to maintain spindle checkpoint function141,142. Thus, the APC/C itself initiates events leading to the inactivation of the spindle checkpoint, and consequently, more APC/C-activation. Such a mechanism holds great potential for positive feedback-regulation, which could explain the switch-like nature of spindle checkpoint inactivation.

Biological switches solely built on positive-feedback loops are difficult to keep under control - here, spindle checkpoint inactivation could be brought about by local fluctuations in p31comet. The spindle checkpoint, however, employs an additional layer of ubiquitin-dependent regulation to protect cells against unscheduled sister chromatid separation. In early mitosis, when chromosomes attempt to achieve bipolar spindle attachment, the DUB Usp44 reverts the ubiquitination of Cdc20 and stabilizes Cdc20-Mad2-complexes46. Loss of Usp44 abrogates the spindle checkpoint and leads to widespread chromosome missegregation. The phenotype of Usp44-depletion can be rescued by co-depletion of UbcH10, providing evidence that Usp44 directly opposes the UbcH10-dependent ubiquitination underlying spindle checkpoint silencing. The ongoing competition between ubiquitination and deubiquitination results in a very dynamic regulation of the spindle checkpoint, and allows cells to rapidly pull the trigger leading to sister chromatid separation.

3.2.2 Ubiquitination step by step: the G2/M-checkpoint

A key feature of the spindle checkpoint is its regulation by reversible ubiquitination. A variation on this theme is played by the G2/M-checkpoint, which impairs entry of cells into mitosis in response to damaged DNA. An important component of the G2/M-checkpoint is the ubiquitin ligase Brca1/Bard1, activation of which blocks mitotic entry through inhibition of cyclin B1/Cdk1143. The loss of ubiquitination by Brca1/Bard1, which occurs in breast cancer cells harboring mutations in the Brca1 RING-finger, abrogates the function of the G2/M-checkpoint144. Such cells can enter mitosis despite DNA damage, and accumulate potentially harmful mutations.

Just like the APC/C, Brca1/Bard1 is closely regulated by non-proteolytic ubiquitination. Following DNA damage, cells activate the kinases ATM and ATR, which phosphorylate a histone, H2AX, and a scaffold protein, Mdc1. Together, γH2AX and Mdc1 form a platform on which DNA repair proteins and G2/M-checkpoint mediators are assembled. One of the earliest proteins to be recruited is the ubiquitin ligase Rnf8, which recognizes phosphorylated Mdc1 through an N-terminal FHA-domain145–147. Rnf8 and its E2 Ubc13 decorate histones at the sites of damage with K63-linked ubiquitin chains75. These K63-linked ubiquitin chains are recognized by a ubiquitin-binding protein, Rap80, which together with Ccdc98/Abraxas recruits the Brca1/Bard1-tumor suppressors148–151. Further ubiquitination by Brca1/Bard1 coordinates later events of DNA repair and elicits the checkpoint-dependent G2/M-arrest. There are only few substrates of Brca1/Bard1 known at sites of DNA damage, including the CtIP protein mutated in cancer152. Rather than promoting CtIP-degradation, its Brca1/Bard-dependent ubiquitination stabilizes the interaction of CtIP with damaged DNA and may promote its function in DNA end resection153. Loss of Rnf8, Brca1/Bard1, or Ubc13 all block the function of the G2/M-checkpoint.

Reminiscent of the regulation of the spindle checkpoint by antagonistic ubiquitination (APC/C, UbcH10) and deubiquitination (Usp44), the Rap80/Brca1/Bard1-complex also contains a deubiquitinating enzyme, Brcc36154. Another DUB, Bap1, had also been shown to bind Brca1155. The activity of Brcc36 is required for G2/M-checkpoint function, but specific substrates have yet to be identified. Thus, both cell cycle checkpoints are regulated by reversible and non-proteolytic ubiquitination.

3.2.3 Ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis in cell cycle checkpoints

Sometimes, cell cycle checkpoints have to resort to more radical means to grant a battered cell enough time to repair the damage. Checkpoints then trigger the degradation of regulators, which are required for entry into the next cell cycle stage. A point in case is made by the intra-S checkpoint, which is activated when cells encounter DNA damage during replication. Activation of the intra-S checkpoint promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of the Cdc25A phosphatase156–158, which would otherwise activate Cdk kinases and promote cell cycle progression. The degradation of Cdc25A therefore stalls cell cycle progression in S phase. The intra-S checkpoint depends on the same ATM, ATR, and Chk kinases as the aforementioned G2/M-checkpoint, and Chk1 is required for the ubiquitination of Cdc25A by SCFβTrCP 157. The failure to degrade Cdc25A, for example by mutation of Chk1 kinase, allows Cdk activation and cell cycle progression despite DNA damage, thus compromising the fidelity of replication. Not surprisingly, high levels of Cdc25A are frequently observed in tumors and correlate with poor prognosis159

Cell cycle checkpoints can also turn the tables and inhibit degradation events required for cell cycle progression. The tumor suppressor p53, for example, impairs cell cycle progression in response to DNA damage. To ensure that cells are not inadvertently slowed down, p53 is constantly degraded following its ubiquitination by the E3 Mdm238. The detection of DNA damage decreases the activity of Mdm2 towards p53 by several means, including impaired p53 binding, reduced catalytic activity of Mdm2, and deubiquitination38,40. The complete inhibition of Mdm2 leads to stabilization and activation of p53, which can then promote the synthesis of the CDK-inhibitor p21, leading to cell cycle arrest. Mdm2 can also be partially inactivated, which results in p53-monoubiquitination rather than multiubiquitination109. As shown with ubiquitin fusion proteins, monoubiquitination of p53 triggers its nuclear export by exposing a nuclear export signal that is recognized by the export factor Crm1160. Thus, under those conditions, p53 is only transiently inhibited - the cell remains skeptical enough to retain some p53 just in case.

3.3 Regulation of growth factor signaling by ubiquitination

The role of ubiquitin in coordinating proliferation with development will serve as a final example to illustrate the intricate mechanisms of ubiquitin-dependent cell cycle control. As already mentioned, mammalian cells decide whether to proliferate or differentiate by recognizing a mixture of extracellular growth and differentiation factors. Cells integrate the signals emerging from multiple receptors before committing to a further round of proliferation. The overexpression of a single receptor disturbs this fine-tuned machinery, and results in prolonged signaling and inappropriate cell cycle progression. To limit growth factor signaling, ligand-engaged growth factor receptors are downregulated by ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis. If the activity of the responsible E3 is crippled, cells proliferate without much restrain and the afflicted organism is likely to develop cancer.

3.3.1 EGF-Receptors

The importance of endocytosis for appropriate growth-factor signaling and cell cycle regulation is illustrated by the epidermal growth factor receptor, EGFR. Inhibition of EGFR endocytosis or EGFR overexpression are tightly linked to the development of breast cancer. By contrast, the downregulation of EGFR kinase activity or the application of humanized monoclonal antibodies against EGFR has been proven to be of therapeutic benefit161,162.

After engagement with its ligand, the dimerization of EGFR induces its autophosphorylation and activation. This triggers intracellular signaling cascades, but at the same time, also promotes EGFR internalization by endocytosis and routing to lysosomal compartment. The complete inactivation of EGFR requires its degradation in the lysosome. Although internalization of EGFR can occur in the absence of ubiquitination, its targeting to the lysosomes depends on K63-linked ubiquitin chains67,76. The components directly binding to ubiquitin163,164. Thus, ubiquitination is essential for the efficient inactivation of EGFR, and constitutes an important negative feedback loop to limit growth factor signaling.

The activated EGFR is ubiquitinated by the RING-E3 c-Cbl165. c-Cbl is paired up with activated EGFR through the adapter molecule Grb, and through recognition of an autophosphorylated tyrosine residue of EGFR by the TKB-domain of c-Cbl166. The activity of c-Cbl is absolutely required for EGFR-internalization. It is known that c-Cbl, in addition to EGFR, has to ubiquitinate other proteins during endocytosis, which could be substrate adaptors or components of the endocytic machinery.

Mutants of c-Cbl underscore the importance of EGFR-endocytosis for cell cycle regulation. A retroviral version, v-Cbl, lacks residues at its C-terminus and is unable to ubiquitinate EGFR167. v-Cbl behaves like a dominant negative mutant that protects EGFR from ubiquitination by c-Cbl expressed in the host cell. Prolonged EGFR signaling causes aberrant cell cycle progression, and indeed, v-Cbl expression after retroviral infection leads to increased B cell proliferation, lymphoma, and myelogenous leukemia. In a similar manner, mutations in the RING-domain of c-Cbl that block its capability to ubiquitinate and downregulate EGFR, lead to prolonged growth factor signaling, aberrant cell cycle control, and cancer166.

A recurrent theme in ubiquitin-dependent cell cycle regulation is the opposition of E3s by DUBs, which provides the basis for dynamic regulation. So it comes at no surprise that the lysosomal targeting of activated EGFR is subject to DUB-regulation. At least two human DUBs regulate EGFR downregulation, AMSH and Usp8/UbpY168,169. Usp8 is itself a cell cycle regulated protein, which is absent from quiescent cells and is only expressed after these cells had been stimulated to re-enter the cell cycle by growth factor signaling43. The DUBs function at multiple stages of EGFR endocytosis, and control the ubiquitination status of cargo and of components of the endocytic machinery. An oncogenic translocation fusing Usp8 to the PI-3K–subunit p85β lends support to an important function of these enzymes in cell cycle control170.

3.3.2 TGF-β signaling

TGF-β and related cytokines impair proliferation and promote differentiation in several tissues171. TGF-β ligands are recognized by heterodimeric receptors (TR-I/TR-II), leading to activation of their kinase activity and trans-phosphorylation. The activated TR-I phosphorylates receptor-Smad proteins (R-Smads), allowing them to bind Smad4, travel to the nucleus, and activate the transcription of genes regulating proliferation and differentiation. Loss of TGF-β signaling leads to aberrant cell cycle progression, and has been firmly linked to tumorigenesis and metastasis.

A class of inhibitory Smad proteins downregulate TGF-β signaling by stimulating the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of activated receptors. Smad7, for example, teams up with a ubiquitin ligase, Smurf2172. The Smad7-Smurf2-complex is transported to cholesterol-rich caveolae, which contain internalized activated TR-I/TR-II. At this time, Smad7 presents the E2 UbcH7 to the HECT-E3 Smurf2, thereby stimulating Smurf2-dependent ubiquitination reactions173. This leads to modification of both Smad7 and the TRs, and targets Smad7 for proteasomal and the TRs for lysosomal degradation.

TGF-β signaling is regulated by ubiquitin-dependent processes at multiple levels, and provides a final example for the complexity of ubiquitin-dependent cell cycle control. Key substrates in the ubiquitin-dependent regulation of TGF-β signaling are the Smads. They can be ubiquitinated by a variety of ubiquitin ligases, such as Smurf1, Smurf2, the HECT-E3s Nedd4-2 and Itch, the U-box E3 CHIP, or SCF174–176. This can have distinct consequences, which may be caused by different types of ubiquitination (monoubiquitination versus chains of different topology). For example, whereas Smad3 ubiquitination by Nedd4-2 stimulates its proteasomal degradation, the modification of Smad3 by Itch activates its transcription activator function. The increased degradation of Smads abolishes the capability of cells to respond to anti-mitogenic TGF-β signaling. This is exemplified by the overexpression of the E3 Ectodermin, which targets Smad4 for unscheduled degradation and is found in intestinal tumors177.

4. Summary: common themes in ubiquitin dependent cell cycle control

Ubiquitination is an essential regulator of cell cycle progression in all eukaryotes. It controls a wide variety of reactions important for proliferation and development, such as progression through the cell cycle program, function of cell cycle checkpoints, and coordination of proliferation with development. Ubiquitination can exert specific control over so many processes by changing the abundance or the activity of modified proteins. Ubiquitination itself is tightly regulated and carried out by very specific enzymes. Whether a protein is ubiquitinated or not is often determined by a balance of counteracting ubiquitination and deubiquitination activities. Whenever irreversible transitions have to be accomplished, ubiquitination triggers the proteasomal degradation of crucial regulators. Ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis is also used to dispose of activated growth-factor receptors by targeting them to lysosomes. Finally, non-proteolytic ubiquitination exerts cell cycle control by orchestrating events in cell cycle checkpoints. We believe that the multiple layers of regulation provided by ubiquitin hold great promise for future innovative approaches to arrest the proliferation of cancer cells in more efficient and specific ways than currently available.

Figure 3. Examples of modified substrates in ubiquitin-dependent cell cycle control.

Left panel: Examples of ubiquitinated proteins, which are not degraded upon their modification. In parentheses, the function of the relevant modification in cell cycle control is noted. Right panel: Examples of proteins that are degraded after being ubiquitinated at different times in the cell cycle. In parenthesis, the relevant ubiquitin ligases are noted.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Julia Schaletzky for many stimulating discussions and critically reading the manuscript. We deeply apologize to all authors whose work could not be cited due to space limitations. The work in our laboratory is funded by grants from the NIH, the NIH Director's New Innovator Award, the March of Dimes Foundation, and the Pew Foundation.

Biographies

Michael Rape is an Assistant Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology in the Department of Molecular Biology at the University of California at Berkeley. He received a diploma in biochemistry from Bayreuth University, Germany, in 1999. Michael earned his Ph.D. degree in 2002 with Stefan Jentsch at the Max-Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried, Germany. From there, he went to the U.S. to pursue postdoctoral research with Marc Kirschner at Harvard Medical School in Boston. Michael accepted his current position at Berkeley in the fall of 2006. His lab is interested in dissecting the role of ubiquitination in controlling proliferation and differentiation. Michael has recently received a Pew Scholars Award and an NIH Director's New Innovator Award.

Katherine Wickliffe graduated from Oberlin College with a B.A. in biology. She is currently a graduate student in Molecular and Cell Biology at the University of California, Berkeley in the laboratory of Michael Rape. Her project focuses on identifying novel proteins that regulate the cell cycle via ubiquitin-dependent degradation.

Adam Williamson is a graduate student in Molecular and Cellular Biology at the University of California, Berkeley. He graduated from Carleton College in Northfield, MN with a B.A. degree in Biology. Adam currently studies in Michael Rape's laboratory at Berkeley. His project focuses on identifying new ubiquitin ligases that control mitotic spindle formation.

Lingyan Jin is a graduate student in department of Molecular and Cell Biology at the University of California, Berkeley. Before coming to the US two years ago, she graduated from Fudan University in China with a B.S. degree in Biological Sciences. Lingyan currently works in the laboratory of Michael Rape on identifying new enzymes involved in protein degradation during stem cell differentiation.

References

- 1.Masui Y, Markert CL. J. Exp. Zool. 1971;177:129. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401770202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newport JW, Kirschner MW. Cell. 1984;37:731. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cyert MS, Kirschner MW. Cell. 1988;53:185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gautier J, Minshull J, Lohka M, Glotzer M, Hunt T, Maller JL. Cell. 1990;60:487. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90599-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon MJ, Glotzer M, Lee TH, Philippe M, Kirschner MW. Cell. 1991;63:1013. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90504-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans T, Rosenthal ET, Youngblom J, Distel D, Hunt T. Cell. 1983;33:389. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90420-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray AW, Solomon MJ, Kirschner MW. Nature. 1989;339:280. doi: 10.1038/339280a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glotzer M, Murray AW, Kirschner MW. Nature. 1991;349:132. doi: 10.1038/349132a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciechanover A, Heller H, Elias S, Haas AL, Hershko A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:1365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hershko A, Ciechanover A, Rose IA. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:1525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciechanover A, Ben-Saadon R. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Herr RA, Chua WJ, Lybarger L, Wiertz EJ, Hansen TH. J. Cell Biol. 2007;177:613. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cadwell K, Coscoy L. Science. 2005;309:127. doi: 10.1126/science.1110340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ravid T, Hochstrasser M. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:422. doi: 10.1038/ncb1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dye BT, Schulman BA. Annu. Rev. Biophy. Biomol. Struct. 2007;36:131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciechanover A, Elias S, Heller H, Hershko A. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:2537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciechanover A, Finley D, Varshavsky A. Cell. 1984;37:57. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin J, Li X, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Nature. 2007;447:1135. doi: 10.1038/nature05902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grenfell SJ, Trausch-Azar JS, Handley-Gearhart PM, Ciechanover A, Schwartz AL. Biochem. J. 1994;300:701. doi: 10.1042/bj3000701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finley D, Ciechanover A, Varshavsky A. Cell. 1984;37:43. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang DT, Hunt HW, Zhuang M, Ohi MD, Holton JM, Schulman BA. Nature. 2007;445:394. doi: 10.1038/nature05490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pohl C, Jentsch S. Cell. 2008;132:832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joazeiro CA, Weissman AM. Cell. 2000;102:549. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aravind L, Koonin EV. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:R132. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozkan E, Yu H, Deisenhofer J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:18890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509418102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reverter D, Lima CD. Nature. 2005;435:687. doi: 10.1038/nature03588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kee Y, Huibregtse JM. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;354:329. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheffner M, Huibregtse JM, Vierstra RD, Howley PM. Cell. 1993;75:495. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu H, Kavsak P, Abdollah S, Wrana JL, Thomsen GH. Nature. 1999;400:687. doi: 10.1038/23293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Guglielmo GM, Le Roy C, Goodfellow AF, Wrana JL. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:410. doi: 10.1038/ncb975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sundvall M, Korhonen A, Paatero I, Gaudio E, Melino G, Croce CM, Aqeilan RI, Elenius K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:4162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708333105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodrigo-Brenni MC, Morgan DO. Cell. 2007;130:127. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.King RW, Peters JM, Tugendreich S, Rolfe M, Hieter P, Kirschner MW. Cell. 1995;81:279. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sudakin V, Ganoth D, Dahan A, Heller H, Hershko J, Luca FC, Ruderman JV, Hershko A. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1995;6:185. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zachariae W, Shin TH, Galova M, Obermaier B, Nasmyth K. Science. 1996;274:1201. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 2005;6:9. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Starita LM, Parvin JD. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:345. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks CL, Gu W. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:307. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nijman SM, Luna-Vargas MP, Velds A, Brummelkamp TR, Dirac AM, Sixma TK, Bernards R. Cell. 2005;123:773. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song L, Rape M. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2008;20:156. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ambroggio XI, Rees DC, Deshaies RJ. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohn MA, Kowal P, Yang K, Haas W, Huang TT, Gygi SP, D’Andrea AD. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:786. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naviglio S, Matteucci C, Matoskova B, Nagase T, Nomura N, Di Fiore PP, Draetta GF. EMBO J. 1998;17:3241. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stegmeier F, Sowa ME, Nelapa G, Gygi SP, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703268104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang TT, Nijman SMB, Mirchandani KD, Galardy PJ, Cohn MA, Haas W, Gygi SP, Ploegh HL, Bernards R, D’Andrea AD. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:339. doi: 10.1038/ncb1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stegmeier F, Rape M, Draviam VM, Nalepa G, Sowa ME, Ang XL, McDonald ER, Li MZ, Hannon GJ, Sorger PK, Kirschner MW, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. Nature. 2007;446:876. doi: 10.1038/nature05694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brummelkamp TR, Nijman SMB, Dirac AMG, Bernards R. Nature. 2003;424:797. doi: 10.1038/nature01811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thrower JS, Hoffman L, Rechsteiner M, Pickart C. EMBO J. 2000;19:94. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elsasser S, Finley D. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:742. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schreiner P, Chen X, Husnjak K, Randles L, Zhang N, Elsasser S, Finley D, Dikic I, Walters KJ, Groll M. Nature. 2008;453:548. doi: 10.1038/nature06924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Husnjak K, Elsasser S, Zhang N, Chen X, Randles L, Shi Y, Hofmann K, Walters KJ, Finley D, Dikic I. Nature. 2008;453:481. doi: 10.1038/nature06926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guédat P, Colland F. BMC Biochem. 2007;8:S14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-8-S1-S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thornton BR, Toczyski DP. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3069. doi: 10.1101/gad.1478306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sabile A, Meyer AM, Wirbelauer C, Hess D, Kogel U, Scheffner M, Krek W. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:5994. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01630-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tang Z, Li B, Bharadwaj R, Zhu H, Ozkan E, Hakala K, Deisenhofer J, Yu H. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:3839. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.12.3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jin J, Cardozo T, Lovering RC, Elledge SJ, Pagano M, Harper JW. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2573. doi: 10.1101/gad.1255304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peters JM. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:644. doi: 10.1038/nrm1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu H. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:3. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clevers H. Cell. 2006;127:469. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kraft C, Herzog F, Gieffers C, Mechtler K, Hagting A, Pines J, Peters JM. EMBO J. 2003;22:6598. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rape M, Kirschner MW. Nature. 2004;432:588. doi: 10.1038/nature03023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fang G, Yu H, Kirschner MW. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1871. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miller JJ, Summers MK, Hansen DV, Nachury MV, Lehman NL, Loktev A, Jackson PK. Genes Dev. 2005;20:2410. doi: 10.1101/gad.1454006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang Z, Bharadwaj R, Li B, Yu H. Dev. Cell. 2001;1:227. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu RS, Kohn KW, Bonner WM. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:5916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nicassio F, Corrado N, Vissers JH, Areces LB, Bergink S, Marteijn JA, Geverts B, Houtsmuller AB, Vermeulen W, Di Fiore P.P, Citterio E. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1972. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sigismund S, Woelk T, Puri C, Maspero E, Tacchetti C, Transidico P, Di Fiore PP, Polo S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:2760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409817102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoege C, Pfander B, Moldovan GL, Pyrowolakis G, Jentsch S. Nature. 2002;419:135. doi: 10.1038/nature00991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eddins MJ, Varadan R, Fushman D, Pickart CM, Wolberger C. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;367:204. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Varadan R, Assfalg M, Haririnia A, Raasi S, Pickart C, Fushman D. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:7055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peng J, Schwartz D, Elias JE, Thoreen CC, Cheng D, Marsischky G, Roelofs J, Finley D, Gygi SP. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:921. doi: 10.1038/nbt849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jin L, Williamson A, Banerjee S, Philipp I, Rape M. Cell. 2008;133:653. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kirkpatrick DS, Hathaway NA, Hanna J, Elsasser S, Rush J, Finley D, King RW, Gygi SP. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:700. doi: 10.1038/ncb1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Deng L, Wang C, Spencer E, Yang L, Braun A, You J, Slaughter C, Pickart C, Chen ZJ. Cell. 2000;103:351. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang B, Elledge SJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710061104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang F, Kirkpatrick D, Jiang X, Gygi S, Sorkin A. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:737. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Eddins MJ, Carlile CM, Gomez KM, Pickart CM, Wolberger C. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:915. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petroski MD, Zhou X, Dong G, Daniel-Issakani S, Payan DG, Huang J. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:29936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703911200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Windheim M, Peggie M, Cohen P. Biochem. J. 2008;409:723. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Topper LM, Bastians H, Ruderman JV, Gorbsky GJ. J. Cell Biol. 2001;154:707. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carrano AC, Eytan E, Hershko A, Pagano M. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:193. doi: 10.1038/12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Cell. 2005;123:1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Townsley FM, Aristarkhov A, Beck S, Hershko A, Ruderman JV. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:2362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Reddy SK, Rape M, Margansky WA, Kirschner MW. Nature. 2007;446:921. doi: 10.1038/nature05734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Skoufias DA, Indorato RL, Lacroix F, Panopoulos A, Margolis RL. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:671. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wolf F, Wandke C, Isenberg N, Geley S. EMBO J. 2006;25:2802. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Potapova TA, Daum JR, Pittman BD, Hudson JR, Jones TN, Satinover DL, Stukenberg PT, Gorbsky GJ. Nature. 2006;440:954. doi: 10.1038/nature04652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chu IM, Hengst L, Slingerland JM. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:253. doi: 10.1038/nrc2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sclafani RA, Holzen TM. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2007;41:237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nakayama K, Nagahama H, Minamishima YA, Miyake S, Ishida N, Hatakeyama S, Kitagawa M, Iemura S, Natsume T, Nakayama KI. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:661. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chu I, Sun J, Arnaout A, Kahn H, Hanna W, Narod S, Sun P, Tan CK, Hengst L, Slingerland J. Cell. 2007;128:281. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Grimmler M, Wang Y, Mund T, Cilensek Z, Keidel EM, Waddell MB, Jäkel H, Kullmann M, Kriwacki RW, Hengst L. Cell. 2007;128:269. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hao B, Zheng N, Schulman BA, Wu G, Miller JJ, Pagano M, Pavletich NP. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang HY, Zhou BP, Hung MC, Lee MH. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:24735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mamillapalli R, Gavrilova N, Mihaylova VT, Tsvetkov LM, Wu H, Zhang H, Sun H. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:263. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Frescas D, Pagano M. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:438. doi: 10.1038/nrc2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sullivan M, Morgan DO. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:894. doi: 10.1038/nrm2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stewart E, Kobayashi H, Harrison D, Hunt T. EMBO J. 1994;13:584. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rape M, Reddy SK, Kirschner MW. Cell. 2006;124:89. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mathe E, Kraft C, Giet R, Daek P, Peters JM, Glover DM. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1723. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Parry DH, O’Farrell PH. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:671. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Carroll CW, Morgan DO. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:880. doi: 10.1038/ncb871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Marangos P, Carroll J. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:445. doi: 10.1038/ncb1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hopfield JJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1974;71:4135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Geley S, Kramer E, Gieffers C, Gannon J, Peters JM, Hunt T. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:137. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hayes MJ, Kimata Y, Wattam SL, Lindon C, Mao G, Yamano H, Fry AM. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:607. doi: 10.1038/ncb1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Amador V, Ge S, Santamaría PG, Guardavaccaro D, Pagano M. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:462. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wolthuis R, Clay-Farrace L, van Zon W, Yekezare M, Koop L, Ogink J, Medema R, Pines J. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:290. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Li M, Brooks CL, Wu-Baer F, Chen D, Baer R, Gu W. Science. 2003;302:1972. doi: 10.1126/science.1091362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tugendreich S, Tomkiel J, Earnshaw W, Hieter P. Cell. 1995;81:261. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90336-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Raff JW, Jeffers K, Huang JY. J. Cell Biol. 2002;157:1139. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wakefield JG, Huang JY, Raff JW. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1367. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00776-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Acquaviva C, Herzog F, Kraft C, Pines J. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:892. doi: 10.1038/ncb1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ban KH, Torres JZ, Miller JJ, Mikhailov A, Nachury MV, Tung JJ, Rieder CL, Jackson PK. Dev. Cell. 2007;13:29. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Welcker M, Clurman BE. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:83. doi: 10.1038/nrc2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Koepp DM, Schaefer LK, Ye X, Keyomarsi K, Chu C, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. Science. 2001;294:173. doi: 10.1126/science.1065203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Moberg KH, Bell DW, Wahrer DC, Haber DA, Hariharan IK. Nature. 2001;413:311. doi: 10.1038/35095068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Welcker M, Orian A, Jin J, Grim JE, Harper JW, Eisenman RN, Clurman BE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:9085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402770101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tetzlaff MT, Yu W, Li M, Zhang P, Finegold M, Mahon K, Harper JW, Schwartz RJ, Elledge SJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:3338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307875101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Welcker M, Clurman BE. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:7654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Burton JL, Solomon MJ. Genes Dev. 2007;21:655. doi: 10.1101/gad.1511107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ballas N, Grunseich C, Lu DD, Speh JC, Mandel G. Cell. 2005;121:645. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Westbrook TF, Hu G, Ang XL, Mulligan P, Pavlova NN, Liang A, Leng Y, Maehr R, Shi Y, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. Nature. 2008;452:370. doi: 10.1038/nature06780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Guardavaccaro D, Frescas D, Dorrello NV, Peschiaroli A, Multani AS, Cardozo T, Lasorella A, Iavarone A, Chang S, Hernando E, Pagano M. Nature. 2008;452:365. doi: 10.1038/nature06641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Westbrook TF, Martin ES, Schlabach MR, Leng Y, Liang AC, Feng B, Zhao JJ, Roberts TM, Mandel G, Hannon GJ, Depinho RA, Chin L, Elledge SJ. Cell. 2005;121:837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Michel LS, Liberal V, Chatterjee A, Kirchwegger R, Pasche B, Gerald W, Dobles M, Sorger PK, Murty VV, Benezra R. Nature. 2001;409:355. doi: 10.1038/35053094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.van Roessel P, Elliott DA, Robinson IM, Prokop A, Brand AH. Cell. 2004;119:707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Juo P, Kaplan JM. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:2057. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Konishi Y, Stegmuller J, Matsuda T, Bonni S, Bonni A. Science. 2004;303:1026. doi: 10.1126/science.1093712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Stegmü J, Konishi Y, Huynh MA, Yuan Z, Dibacco S, Bonni A. Neuron. 2006;50:389. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wan Y, Liu X, Kirschner MW. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:1027–1039. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lasorella A, Stegmuller J, Guardavaccaro D, Liu G, Carro MS, Rothschild G, de la Torre-Ubieta L, Pagano M, Bonni A, Iavarone A. Nature. 2006;442:471. doi: 10.1038/nature04895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Burke DJ, Stukenberg PT. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:474. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Cohen-Fix O. Cell. 2001;106:137. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00439-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Luo X, Tang Z, Rizo J, Yu H. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:59. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00435-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Mapelli M, Massimiliano L, Santaguida S, Musacchio A. Cell. 2007;131:730. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Luo X, Tang Z, Xia G, Wassmann K, Matsumoto T, Rizo J, Yu H. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:338. doi: 10.1038/nsmb748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Xia G, Luo X, Habu T, Rizo J, Matsumoto T, Yu H. EMBO J. 2004;23:3133. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Rape M, Hoppe T, Gorr I, Kalocay M, Richly H, Jentsch S. Cell. 2001;107:667. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00595-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Braunstein I, Miniowitz S, Moshe Y, Hershko A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:4870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700523104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Palframan WJ, Meehl JB, Jaspersen SL, Winey M, Murray AW. Science. 2007;313:680. doi: 10.1126/science.1127205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Qi W, Yu H. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:3672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Yarden RI, Pardo-Reoyo S, Sgagias M, Cowan KH, Brody LC. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:285. doi: 10.1038/ng837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Ruffner H, Joazeiro CA, Hemmati D, Hunter T, Verma IM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:5134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081068398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Mailand N, Bekker-Jensen S, Faustrup H, Melander F, Bartek J, Lukas C, Lukas J. Cell. 2007;131:887. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Huen MS, Grant R, Manke I, Minn K, Yu X, Yaffe MB, Chen J. Cell. 2007;131:901. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kolas NK, Chapman JR, Nakada S, Ylanko J, Chahwan R, Sweeney FD, Panier S, Mendez M, Wildenhain J, Thomson TM, Pelletier L, Jackson SP, Durocher D. Science. 2007;318:1637. doi: 10.1126/science.1150034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Wang B, Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Zhang D, Smogorzewska A, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ. Science. 2007;316:1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1139476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Sobhian B, Shao G, Lilli DR, Culhane AC, Moreau LA, Xia B, Livingston DM, Greenberg RA. Science. 2007;316:1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1139516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Kim H, Chen J, Yu X. Science. 2007;316:1202. doi: 10.1126/science.1139621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Kim H, Huang J, Chen J. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:710. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Yu X, Fu S, Lai M, Baer R, Chen J. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1721. doi: 10.1101/gad.1431006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Sartori AA, Lukas C, Coates J, Mistrik M, Fu S, Bartek J, Baer R, Lukas J, Jackson SP. Nature. 2007;450:509. doi: 10.1038/nature06337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Dong Y, Hakimi MA, Chen X, Kumaraswamy E, Cooch NS, Godwin AK, Shiekhattar R. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1087. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Jensen DE, et al. Oncogene. 1999;16:1097. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Busino L, Donzelli M, Chiesa M, Guardavaccaro D, Ganoth D, Dorrello NV, Hershko A, Pagano M, Draetta GF. Nature. 2003;426:87. doi: 10.1038/nature02082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Jin J, Shirogane T, Xu L, Nalepa G, Qin J, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3062. doi: 10.1101/gad.1157503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Kanemori Y, Uto K, Sagata N. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Boutros R, Lobjois V, Ducommun B. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:495. doi: 10.1038/nrc2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Carter S, Bischof O, Dejean A, Vousden KH. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:428. doi: 10.1038/ncb1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Leahy DJ. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:291. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Polo S, Pece S, Di Fiore PP. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:156. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Malerød L, Stuffers S, Brech A, Stenmark H. Traffic. 2007;8:1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Saksena S, Sun J, Chu T, Emr SD. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:561. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Levkowitz G, Waterman H, Ettenberg SA, Katz M, Tsygankov AY, Alroy I, Lavi S, Iwai K, Reiss Y, Ciechanover A, Lipkowitz S, Yarden Y. Mol. Cell. 1999;4:1029. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Schmidt MH, Dikic I. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:907. doi: 10.1038/nrm1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Robertson H, Hime GR, Lada H, Bowtell DD. Oncogene. 2000;19:299. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.McCullough J, Row PE, Lorenzo O, Doherty M, Beynon R, Clague MJ, Urbè S. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:160. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Niendorf S, Oksche A, Kisser A, Loehler J, Prinz M, Schorle H, Feller S, Lewitzky M, Horak I, Knobeloch KP. Mol Cell. Biol. 2007;27:5029. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01566-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Janssen JWG, Schleithoff L, Bartram CR, Schulz AS. Oncogene. 1998;16:1767. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Schmierer B, Hill CS. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:970. doi: 10.1038/nrm2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Kavsak P, Rasmussen RK, Causing CG, Bonni S, Zhu H, Thomsen GH, Wrana JL. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1365. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]