Abstract

Background

Many previous studies have documented seasonal variation in suicides globally. We re-assessed the seasonal variation of suicides in Finland and tried to relate it to the seasonal variation in daylength and ambient temperature and in the discrepancy between local time and solar time.

Methods

The daily data of all suicides from 1969 to 2003 in Finland (N = 43,393) were available. The calendar year was divided into twelve periods according to the length of daylight and the routinely changing time difference between sun time and official time. The daily mean of suicide mortality was calculated for each of these periods and the 95% confidence intervals of the daily means were used to evaluate the statistical significance of the means. In addition, daily changes in sunshine hours and mean temperature were compared to the daily means of suicide mortality in two locations during these afore mentioned periods.

Results

A significant peak of the daily mean value of suicide mortality occurred in Finland between May 15th and July 25th, a period that lies symmetrically around the solstice. Concerning the suicide mortality among men in the northern location (Oulu), the peak was postponed as compared with the southern location (Helsinki). The daily variation in temperature or in sunshine did not have significant association with suicide mortality in these two locations.

Conclusions

The period with the longest length of the day associated with the increased suicide mortality. Furthermore, since the peak of suicide mortality seems to manifest later during the year in the north, some other physical or biological signals, besides the variation in daylight, may be involved. In order to have novel means for suicide prevention, the assessment of susceptibility to the circadian misalignment might help.

Keywords: circadian clock, suicide, light-dark transition, sunshine, temperature

Background

Current data on the routinely occurring peaks of deaths from suicide are conflicting [1,2]. However, for the past four decades in Finland, the seasonal pattern has been stronger the lower the suicide mortality has been [3]. There is a clear peak of suicide occurrence around May or June [4-7] and a preceding peak in suicide attempts around April [8]. Furthermore, another smaller peak of suicide occurrence exists around October [7,9]. These two mortality peaks, being similar and more robust the further away the country locates from the equator, have been explained by socio-demographic and socio-economic factors [10], but since this seasonal pattern has existed for decades [11], if not centuries [12], biological factors are likely.

Major depressive episodes are known to contribute to suicide substantially [13,14], and a history of mood disorders and psychiatric hospitalization associates clearly with the seasonal occurrence of suicides [15,16]. Desynchronization of physiological rhythms, e.g. desynchronization of the circadian rhythm of core body temperature with the sleep-wake cycle [17-19] and some clock gene variants [20,21], can be associated with mood disorders. Based on our earlier psychological autopsy studies of death from suicide [22] and the data from the nationwide suicide program in Finland [23], we hypothesized that the circadian misalignment among the depressed may increase during spring, and thereby predispose to suicidal behaviors [24].

Rest-activity cycles during the day [25] and sleep stages at night [26] are controlled by circadian clocks, but they are frequently disturbed among the depressed. Furthermore, the principal circadian clock entrains to the sun light [27-29], by tracking the daily changes in rise and set times of the sun and the variation in the length of the day [30-32]. Thus, the timing of light exposure is relevant to entrainment and influences the course of mood disorders [33,34]. Therefore, we hypothesized that it is the key to the suicide mortality peaks whether the light-dark transitions give the principal circadian pacemaker a signal to accelerate or decelerate, especially among the depressed. In addition, since sunshine and ambient temperature are potential time-givers, modulate the function of biological clocks [35], and associate with deaths from suicide [3,36], we aimed to test their effect, as well.

Methods

Statistics Finland http://www.stat.fi provided us with the daily data of 43,393 suicides, 33,993 of men and 9400 (22%) of women, committed in Finland during the 35-year period of 1969 to 2003 (Tables 1 and 2). Two phenomena, which affect the timing and the speed of the light-dark transitions regularly each year, were selected a priori as the potential factors that might challenge the biological clocks and produce circadian misalignment. First, we focused on the length of the photoperiod, because at high to temperate latitudes around spring and fall equinoxes the transitions between day and night are most rapid and the durations of twilight short, as a consequence of the rotation of the earth. Second, we focused on the constant mismatch between the sun time (hereafter ST) and the coordinated universal time (hereafter UCT), arising from the earth's tilt and elliptical orbit around the sun.

Table 1.

Men's suicides in numbers during the study period

| Oulu | Helsinki | Finland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Men | S |

per 100 000 |

Men | S |

per 100 000 |

Men | S |

per 100 000 |

| 1969 | 42 447 | 11 | 25.92 | 272 321 | 110 | 40.39 | 2 230 217 | 850 | 38.11 |

| 1970 | 41 412 | 13 | 31.39 | 266 174 | 108 | 40.58 | 2 219 985 | 763 | 34.37 |

| 1971 | 42 798 | 11 | 25.70 | 271 393 | 117 | 43.11 | 2 234 037 | 781 | 34.96 |

| 1972 | 43 436 | 22 | 50.65 | 275 378 | 132 | 47.93 | 2 249 051 | 874 | 38.86 |

| 1973 | 44 127 | 27 | 61.19 | 277 205 | 109 | 39.32 | 2 262 142 | 849 | 37.53 |

| 1974 | 45 082 | 22 | 48.80 | 278 485 | 131 | 47.04 | 2 273 815 | 921 | 40.51 |

| 1975 | 45 815 | 22 | 48.02 | 278 628 | 128 | 45.40 | 2 282 115 | 924 | 40.49 |

| 1976 | 46 069 | 29 | 62.95 | 278 693 | 152 | 54.54 | 2 286 392 | 967 | 42.29 |

| 1977 | 46 444 | 22 | 47.37 | 277 978 | 154 | 55.40 | 2 295 668 | 962 | 41.91 |

| 1978 | 46 609 | 13 | 27.89 | 277 735 | 156 | 56.17 | 2 300 790 | 963 | 41.86 |

| 1979 | 46 533 | 18 | 38.68 | 278 569 | 133 | 47.74 | 2 306 784 | 935 | 40.53 |

| 1980 | 46 779 | 24 | 51.31 | 279 456 | 145 | 51.89 | 2 314 843 | 962 | 41.56 |

| 1981 | 47 343 | 21 | 44.36 | 280 580 | 151 | 53.82 | 2 327 473 | 904 | 38.84 |

| 1982 | 48 179 | 18 | 37.36 | 282 751 | 134 | 47.39 | 2 342 869 | 905 | 38.63 |

| 1983 | 48 331 | 25 | 51.73 | 284 565 | 130 | 45.68 | 2 357 172 | 938 | 39.79 |

| 1984 | 48 620 | 25 | 51.42 | 286 092 | 149 | 52.08 | 2 369 228 | 988 | 41.70 |

| 1985 | 49 065 | 23 | 46.88 | 287 858 | 113 | 39.26 | 2 377 780 | 964 | 40.54 |

| 1986 | 49 405 | 30 | 60.72 | 290 370 | 149 | 51.31 | 2 385 866 | 1023 | 42.88 |

| 1987 | 49 890 | 28 | 56.12 | 292 935 | 137 | 46.77 | 2 392 868 | 1068 | 44.63 |

| 1988 | 50 138 | 44 | 87.76 | 294 242 | 150 | 50.98 | 2 401 368 | 1112 | 46.31 |

| 1989 | 50 951 | 29 | 56.92 | 295 665 | 160 | 54.12 | 2 412 760 | 1121 | 46.46 |

| 1990 | 51 623 | 33 | 63.93 | 298 420 | 198 | 66.35 | 2 426 204 | 1199 | 49.42 |

| 1991 | 52 254 | 35 | 66.98 | 302 609 | 185 | 61.14 | 2 443 042 | 1193 | 48.83 |

| 1992 | 52 959 | 36 | 67.98 | 306 298 | 204 | 66.60 | 2 457 282 | 1160 | 47.21 |

| 1993 | 53 495 | 35 | 65.43 | 311 134 | 172 | 55.28 | 2 470 196 | 1112 | 45.02 |

| 1994 | 54 661 | 23 | 42.08 | 316 367 | 176 | 55.63 | 2 481 649 | 1080 | 43.52 |

| 1995 | 56 132 | 26 | 46.32 | 322 074 | 179 | 55.58 | 2 491 701 | 1081 | 43.38 |

| 1996 | 57 436 | 26 | 45.27 | 327 168 | 131 | 40.04 | 2 500 596 | 966 | 38.63 |

| 1997 | 58 482 | 36 | 61.56 | 332 113 | 158 | 47.57 | 2 509 098 | 1039 | 41.41 |

| 1998 | 59 606 | 26 | 43.62 | 337 297 | 121 | 35.87 | 2 516 075 | 965 | 38.35 |

| 1999 | 61 025 | 40 | 65.55 | 341 125 | 139 | 40.75 | 2 523 026 | 961 | 38.09 |

| 2000 | 62 800 | 28 | 44.59 | 344 520 | 143 | 41.51 | 2 529 341 | 879 | 34.75 |

| 2001 | 64 116 | 31 | 48.35 | 347 925 | 150 | 43.11 | 2 537 597 | 936 | 36.89 |

| 2002 | 64 995 | 22 | 33.85 | 349 121 | 139 | 39.81 | 2 544 916 | 825 | 32.42 |

| 2003 | 65 965 | 29 | 43.96 | 350 334 | 119 | 33.97 | 2 552 893 | 823 | 32.24 |

The yearly male population, number of suicides(S), and suicide mortality for men in Oulu, Helsinki, and Finland from 1969 to 2003.

Table 2.

Women's suicides in numbers during the study period

| Oulu | Helsinki | Finland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Women | S |

per 100 000 |

Women | S |

per 100 000 |

Women | S |

per 100 000 |

| 1969 | 46 245 | 5 | 10.81 | 333 502 | 43 | 12.89 | 2 384 060 | 246 | 10.32 |

| 1970 | 45 656 | 4 | 8.76 | 325 034 | 58 | 17.84 | 2 378 351 | 220 | 9.25 |

| 1971 | 46 474 | 5 | 10.76 | 330 205 | 58 | 17.57 | 2 391 875 | 222 | 9.28 |

| 1972 | 47 633 | 5 | 10.50 | 333 507 | 57 | 17.09 | 2 404 350 | 239 | 9.94 |

| 1973 | 48 302 | 6 | 12.42 | 335 687 | 60 | 17.87 | 2 416 619 | 249 | 10.30 |

| 1974 | 49 272 | 11 | 22.33 | 337 470 | 47 | 13.93 | 2 428 572 | 255 | 10.50 |

| 1975 | 50 132 | 5 | 9.97 | 337 570 | 72 | 21.33 | 2 438 377 | 254 | 10.42 |

| 1976 | 50 410 | 12 | 23.81 | 336 980 | 66 | 19.59 | 2 444 444 | 253 | 10.35 |

| 1977 | 50 691 | 8 | 15.78 | 335 057 | 54 | 16.12 | 2 451 299 | 258 | 10.53 |

| 1978 | 50 964 | 11 | 21.58 | 334 547 | 53 | 15.84 | 2 457 298 | 237 | 9.65 |

| 1979 | 51 188 | 6 | 11.72 | 334 981 | 60 | 17.91 | 2 464 508 | 242 | 9.82 |

| 1980 | 51 582 | 4 | 7.76 | 335 630 | 63 | 18.77 | 2 472 935 | 264 | 10.68 |

| 1981 | 52 237 | 1 | 1.91 | 336 511 | 56 | 16.64 | 2 484 677 | 239 | 9.62 |

| 1982 | 53 059 | 10 | 18.85 | 338 116 | 59 | 17.45 | 2 498 846 | 267 | 10.69 |

| 1983 | 53 225 | 6 | 11.27 | 339 108 | 56 | 16.51 | 2 512 686 | 249 | 9.91 |

| 1984 | 53 443 | 3 | 5.61 | 340 162 | 54 | 15.88 | 2 524 520 | 253 | 10.02 |

| 1985 | 53 976 | 4 | 7.41 | 341 781 | 58 | 16.97 | 2 532 884 | 249 | 9.83 |

| 1986 | 54 349 | 12 | 22.08 | 343 576 | 53 | 15.43 | 2 539 778 | 287 | 11.30 |

| 1987 | 54 760 | 10 | 18.26 | 346 162 | 65 | 18.78 | 2 545 734 | 301 | 11.82 |

| 1988 | 55 125 | 9 | 16.33 | 346 880 | 62 | 17.87 | 2 552 991 | 296 | 11.59 |

| 1989 | 55 810 | 8 | 14.33 | 347 226 | 58 | 16.70 | 2 561 623 | 297 | 12.59 |

| 1990 | 56 294 | 8 | 14.21 | 348 913 | 90 | 25.79 | 2 572 274 | 324 | 11.60 |

| 1991 | 56 735 | 8 | 14.10 | 352 207 | 74 | 21.01 | 2 585 960 | 306 | 11.83 |

| 1992 | 57 391 | 6 | 10.46 | 354 429 | 77 | 21.73 | 2 597 700 | 297 | 11.43 |

| 1993 | 57 765 | 6 | 10.39 | 358 557 | 72 | 20.08 | 2 607 716 | 293 | 11.24 |

| 1994 | 58 781 | 12 | 20.42 | 363 774 | 77 | 21.17 | 2 617 105 | 307 | 11.73 |

| 1995 | 60 186 | 12 | 19.94 | 369 437 | 65 | 17.59 | 2 625 125 | 309 | 11.77 |

| 1996 | 61 447 | 8 | 13.02 | 373 663 | 69 | 18.47 | 2 631 724 | 282 | 10.72 |

| 1997 | 62 439 | 11 | 17.62 | 378 547 | 68 | 17.96 | 2 638 251 | 284 | 10.77 |

| 1998 | 63 454 | 11 | 17.34 | 382 880 | 57 | 14.89 | 2 643 571 | 268 | 10.14 |

| 1999 | 64 516 | 13 | 20.15 | 386 384 | 68 | 17.60 | 2 648 276 | 254 | 9.59 |

| 2000 | 66 149 | 11 | 16.63 | 389 425 | 66 | 16.95 | 2 651 774 | 292 | 11.01 |

| 2001 | 67 584 | 9 | 13.32 | 391 649 | 62 | 15.83 | 2 657 304 | 271 | 10.20 |

| 2002 | 68 297 | 11 | 16.11 | 392 485 | 48 | 12.23 | 2 661 379 | 275 | 10.33 |

| 2003 | 68 878 | 7 | 10.16 | 393 035 | 55 | 13.99 | 2 666 839 | 261 | 9.79 |

The yearly female population, number of suicides(S), and suicide mortality for women in Oulu, Helsinki, and Finland from 1969 to 2003.

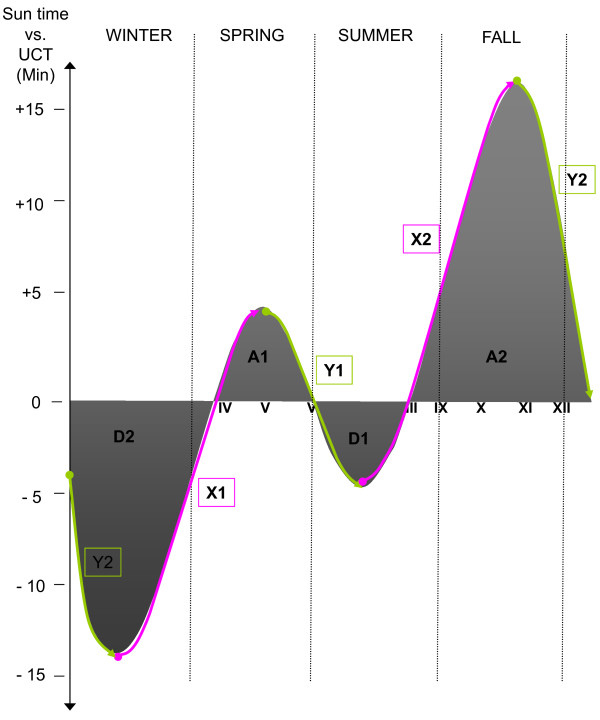

The nominal calendar year was split into twelve periods according to these two phenomena; first into four astronomical seasons, which are determined by spring and fall equinoxes and summer and winter solstices (for the definition, see http://asa.nao.rl.ac.uk/), and second into eight periods, by the equation of time (for the definition, see http://www.nmm.ac.uk/explore/astronomy-and-time/time-facts/the-equation-of-time), as follows (see also Figure 1). From February 11th to May 14th (hereafter marked as X1) and from July 26th to November 3rd (X2) ST goes fast compared with UCT and in between those periods, that is, from May 15th to July 25th (Y1) and from November 4th to February 10th (Y2) it goes slow. Furthermore, another categorization was made based on the equation of time separating periods when ST is either ahead or behind the UCT. In other words, ST is constantly ahead of the UCT, from April 15th to June 13th (A1) and from September 1st to December 25th (A2), and constantly behind the UCT, from June 14th to August 31st (D1), and from December 26th to April 14th (D2). Hence, ST deviates from UCT constantly and is maximally behind at February 11th (approximately 14 minutes) and vice versa maximally ahead at November 3rd (approximately 16 minutes). The Almanac Office at the University of Helsinki http://almanakka.helsinki.fi/ both provided the dates for the astronomical seasons and calculated the dates for the periods (X1, Y1, X2, Y2) of the equation of time, as well as the dates for the periods (A1, D1, A2, D2) through the whole study period.

Figure 1.

Periods according to time of equation and astronomical seasons. During X1(February 11-May 04) and X2 (July 26-November 03) (marked with pink lines) sun time is accelerating, and during Y1 (May 15-July25) and Y2 (November 04-February 10) (marked with green lines) it is decelerating compared with the coordinated universal time (UCT). During A1 (April 15-June13) and A2 (September 01-December 25) sun time stays ahead and during D1 (June 14-August 31) and D2 (December 26-April 14) it stays behind the UCT. Astronomical seasons are separated with dotted vertical lines. During astronomical spring and summer daylight exceeds darkness, and vice versa during astronomical fall and winter darkness exceeds daylight in Finland. Y-axis on the left side presents the time difference (in minutes) that sun time deviates from the UCT.

To evaluate the effect of daily sunshine hours and temperature on suicide mortality, we focused on two cities on a similar longitude but with dissimilar photoperiod: first, Helsinki (60°9.7'N, 24°57.3'E), which is the capital of Finland in the south, and second, Oulu (65°1.0'N, 25°30.0'E), which is a central city of the northern part of the country, 600 km north from Helsinki. In Helsinki 5062 suicides were committed by men, and 2160 by women, whereas 903 by men and 278 by women in Oulu. The Finnish Meteorological Institute http://www.fmi.fi/ provided us with the daily data on sunshine hours and temperature, measured within the 25-km radius from these cities throughout the study period. For the day to day analysis, the daily sunshine, measured in minutes per day, (hereafter S) and the daily temperature, measured in degrees in Celsius and averaged as the daily mean value, (hereafter T) were compared with those on the previous day and changes were marked as (+) indicating an increase, and (-) indicating a decrease from the previous day. Thus, we ended with four types of days according to weather changes, coded as T+S+, T+S-, T-S+, and T-S-, concerning the data from Helsinki and Oulu regions.

In order to take into account the differences in the yearly population sizes within and between Helsinki and Oulu, the daily means of suicides were calculated into daily means of suicide mortality rates (suicides per 100,000), for men and women, per each year, and for both cities (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, in order to control for the different lengths of each period studied, and to avoid the bias of having dominance of certain type of weather changes within any period of the year, the daily mean of suicide mortalities (number of suicides per day, with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) was calculated for each period in separate (Tables 3, 4, and 5).

Table 3.

Astronomical seasons and men's (M) and women's (W) suicide mortality

| Area | Selected Days | Astronomical season | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter | Spring | Summer | Fall | ||||

| M | Finland | All | .099 .094-.103 |

.120 .115-.125 |

.117 .112-.122 |

.106 .101-.111 |

|

| Helsinki | All |

.128 .120-.136 |

.138 .128-.148 |

.135 .123-.147 |

.131 .122-.140 |

||

| T+ | S+ |

.123 .099-.146 |

.135 .122-.147 |

.139 .122-.156 |

.137 .120-.155 |

||

| S- |

.113 .092-.134 |

.144 .125-.163 |

.142 .120-.164 |

.115 .099-.132 |

|||

| T- | S+ |

.122 .108-.136 |

.146 .128-.163 |

.130 .117-.143 |

.133 .118-.147 |

||

| S- |

.122 .097-.146 |

.140 .120-.161 |

.129 .112-.146 |

.144 .116-.172 |

|||

| Oulu | All | .119 .098-.140 |

.141 .123-.160 |

.159 .138-.180 |

.131 .113-.150 |

||

| T+ | S+ |

.107 .050-.163 |

.134 .103-.165 |

.162 .112-.212 |

.152 .077-.227 |

||

| S- |

.097 .059-.135 |

.126 .082-.170 |

.175 .132-.217 |

.147 .101-.193 |

|||

| T- | S+ |

.124 .094-.154 |

.167 .132-.203 |

.156 .115-.197 |

.117 .073-.161 |

||

| S- |

.097 .045-.148 |

.138 .110-.166 |

.132 .086-.178 |

.144 .083-.205 |

|||

| W | Finland | All | .025 .023-.027 |

.031 .030-.032 |

.029 .028-.031 |

.028 .027-030 |

|

| Helsinki | All |

.046 .042-.050 |

.050 .045-.054 |

.049 .045-.054 |

.048 .043-.053 |

||

| T+ | S+ |

.038 .028-.048 |

.056 .046-.065 |

.049 .039-.058 |

.056 .043-.069 |

||

| S- |

.051 .033-.069 |

.049 .041-.056 |

.046 .034-.058 |

.052 .042-.062 |

|||

| T- | S+ |

.042 .036-.049 |

.046 .034-.057 |

.049 .040-.057 |

.049 .039-.059 |

||

| S- |

.052 .039-.065 |

.052 .042-.062 |

.051 .041-.061 |

.045 .031-.059 |

|||

| Oulu | All |

.036 .029-.044 |

.040 .030-.049 |

.042 .032-.051 |

.039 .029-.048 |

||

| T+ | S+ |

.032 .006-.058 |

.031 .016-.046 |

.042 .023-.061 |

.049 .013-.086 |

||

| S- |

.037 .015-.058 |

.030 .015-.043 |

.047 .020-.074 |

.020 .005-.036 |

|||

| T- | S+ |

.041 .019-.063 |

.051 .028-.074 |

.037 .019-.055 |

.043 .019-.067 |

||

| S- |

.028 .000-.055 |

.045 .020-.069 |

.042 .020-.063 |

.047 .018-.076 |

|||

Daily mean of suicide mortality and confidence interval of the mean in aggregate over the years from 1969 to 2003 for men and women, during astronomical seasons in Finland, Helsinki and Oulu, and according to daily changes (+/-) in temperature (T) and sunshine hours(S) in Helsinki and Oulu.

Winter: 21.12-20.03

Spring: 21.03-20.06

Summer: 21.06-22.09

Fall: 23.09-20.12

Table 4.

Accelerating and decelerating periods of the equation of time and men's (M) and women's (W) suicide mortality

| Area | Selected Days | Periods of time of equation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | Y1 | X2 | Y2 | ||||

| M | Finland | All | .109 .105-.114 |

.124 .118-.129 |

.112 .107-.116 |

.101 .096-.106 |

|

| Helsinki | All | .131 .121-.141 |

.142 .130-.154 |

.130 .122-.139 |

.130 .120-.140 |

||

| T+ | S+ |

.139 .116-.161 |

.149 .131-.167 |

.122 .097-.147 |

.124 .097-.151 |

||

| S- |

.151 .123-.179 |

.145 .119-.170 |

.124 .103-.145 |

.110 .088-.131 |

|||

| T- | S+ |

.152 .122-.182 |

.126 .100-.153 |

.135 .121-.150 |

.120 .099-.141 |

||

| S- |

.133 .104-.161 |

.124 .106-.142 |

.138 .116-.160 |

.114 .086-.142 |

|||

| Oulu | All |

.133 .115-.150 |

.146 .124-.167 |

.150 .131-.169 |

.122 104-.140 |

||

| T+ | S+ |

.156 .094-.218 |

.149 .101-.198 |

.206 .122-.290 |

.131 .052-.210 |

||

| S- |

.096 .042-.150 |

.207 .142-.272 |

.165 .112-.217 |

.097 .046-.148 |

|||

| T- | S+ |

.199 .138-.259 |

.140 .090-.190 |

.138 .092-.184 |

.115 .068-.162 |

||

| S- |

.123 .065-.181 |

.158 .114-.201 |

.175 .107-.242 |

.056 .008-.103 |

|||

| W | Finland | All | .028 .027-.029 |

.032 .030-.033 |

.030 .029-.031 |

.025 .024-.027 |

|

| Helsinki | All |

.047 .043-.051 |

.053 .048-.058 |

.050 .045-.054 |

.043 .039-.048 |

||

| T+ | S+ |

.052 .040-.064 |

.055 .046-.065 |

.056 .044-.068 |

.033 .018-.048 |

||

| S- |

.044 .030-.057 |

.059 .047-.072 |

.055 .041-.069 |

.055 .044-.067 |

|||

| T- | S+ |

.051 .032-.070 |

.049 .036-.061 |

.049 .040-.058 |

.036 .028-.045 |

||

| S- |

.051 .034-.067 |

.046 .034-.058 |

.048 .037-.058 |

.045 .025-.065 |

|||

| Oulu | All | .038 .029-.047 |

.045 .034-.057 |

.035 .027-.042 |

.038 .029-.047 |

||

| T+ | S+ S- |

.023 .005-.042 |

.039 .017-.060 |

.044 .014-.074 |

- | ||

|

.035 .012-.058 |

.053 .018-.087 |

.015 .001-.029 |

.026 .002-.050 |

||||

| T- | S+ S- |

.062 .028-.096 |

.030 .006-.054 |

.042 .024-.061 |

.036 .013-.059 |

||

|

.030 .003-.058 |

.060 028-.091 |

.032 .010-.054 |

- | ||||

Daily mean of suicide mortality and confidence interval of the mean in aggregate over the years from 1969 to 2003 for men and women, during accelerating (X1, X2) and decelerating (Y1, Y2) periods of the equation of time in Finland, Helsinki and Oulu, and according to daily changes (+/-) in temperature (T) and sunshine hours(S) in Helsinki and Oulu.

X1: 11.02-14.05

Y1: 15.05-25.07

X2: 26.07-03.11

Y2: 04.11-10.2

Table 5.

Advanced and delayed periods of the equation of time and men's (M) and women's (W) suicide mortality

| Area | Selected days | Periods of time of equation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2 | A1 | D1 | A2 | ||||

| M | Finland | All | .102 .098-.107 |

.125 .120-.130 |

.118 .112-.123 |

.107 .102-.111 |

|

| Helsinki | All |

.128 .121-.136 |

.146 .134-.158 |

.135 .122-.147 |

.130 .122-.139 |

||

| T+ | S+ |

.125 .103-.146 |

.142 .129-.154 |

.141 .123-.159 |

.128 .108-.148 |

||

| S- |

.123 .102-.143 |

.142 .119-.164 |

.145 .121-.169 |

.116 .100-.131 |

|||

| T- | S+ |

.124 .111-.136 |

.162 .137-.187 |

.124 .108-.141 |

.134 .121-.146 |

||

| S- |

.123 .103-.144 |

.147 .124-.171 |

.126 .110-.142 |

.141 .118-.164 |

|||

| Oulu | All |

.125 .107-.144 |

.145 .123-.167 |

.148 .128-.168 |

.139 .119-.159 |

||

| T+ | S+ |

.099 .059-.139 |

.159 .123-.196 |

.137 .088-.185 |

.186 .121-.250 |

||

| S- |

.105 .065-.145 |

.129 .080-.178 |

.177 .129-.225 |

.150 .104-.196 |

|||

| T- | S+ |

.140 .112-.168 |

.155 .103-.208 |

.146 .095-.197 |

.129 .090-.168 |

||

| S- |

.109 .062-.157 |

.137 .097-.176 |

.122 .079-.165 |

.149 .091-.206 |

|||

| W | Finland | All | .026 .024-.027 |

.032 .030-.034 |

.030 .028-.031 |

.028 .027-.030 |

|

| Helsinki | All |

.046 .042-.049 |

.051 .045-.056 |

.051 .046-.056 |

.048 .043-.053 |

||

| T+ | S+ |

.043 .034-.053 |

.058 .047-.069 |

.048 .039-.057 |

.056 .047-.065 |

||

| S- |

.050 .033-.067 |

.047 .033-.062 |

.049 .038-.061 |

.052 .042-.062 |

|||

| T- | S+ |

.041 .034-.048 |

.051 .036-.066 |

.050 .040-.061 |

.048 .040-.056 |

||

| S- |

.048 .039-.058 |

.057 .044-.069 |

.051 .040-.062 |

.048 .037-.059 |

|||

| Oulu | All |

.036 .029-.044 |

.043 .032-.054 |

.041 .030-.053 |

.038 .031-.048 |

||

| T+ | S+ |

.037 .016-.059 |

.031 .013-.050 |

.036 .017-.054 |

.044 .019-.069 |

||

| S- |

.033 .016-.049 |

.033 .013-.054 |

.058 .024-.092 |

.017 .005-.030 |

|||

| T- | S+ |

.045 .026-.063 |

.047 .020-.075 |

.040 .014-.066 |

.040 .022-.058 |

||

| S- |

.025 .002-.048 |

.053 .021-.085 |

.041 .019-.064 |

.039 .020-.057 |

|||

Daily mean of suicide mortality and confidence interval of the mean, in aggregate over the years from 1969 to 2003 for men and women, during advanced (A1, A2) and delayed (D1, D2) periods of the equation of time in Finland, Helsinki and Oulu, and according to daily changes (+/-) in temperature (T) and sunshine hours(S) in Helsinki and Oulu.

A1: 15.04-13.06

D1: 14.06-31.08

A2: 01.09-25.12

D2: 26.12-14.04

Finally, to rule out a potential confounder, we analyzed whether daylight saving time (hereafter DST) had any effect on the suicide mortality. DST was introduced in Finland 1981. From 1981 to 1994 DST lasted from the end of March until the end of September (hereafter DST1), and since 1995 DST has been in use from the end of March until the end of October, as in most parts of Europe (hereafter DST2). We calculated suicide mortality rates during one month period before, and after the transitions into and out of DST, separately for the years 1981 to 1994 (DST1) and years 1995 to 2003 (DST2), for which the suicide mortality rates of the corresponding periods during the years 1969 to 1980 were used as controls (Tables 6, 7, 8, 9,10, and 11).

Table 6.

Men: Daily mean of suicide mortality, and switching into daylight saving time in spring.

| Days | 1969-80* | 1981-2003 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1 m | +1 m | -1 m | +1 m | ||||||

| M | CI | m | CI | m | CI | m | CI | ||

| Finland | All | .097 | .089-.106 | .111 | .102-.121 | .104 | .097-.111 | .117 | .110-.124 |

| Helsinki | All | .114 | .096-.133 | .130 | .114-.146 | .135 | .120-.150 | .137 | .118-.155 |

| T+S+ | .120 | .061-.180 | .160 | .100-.219 | .129 | .084-.173 | .140 | .102-.177 | |

| T+S- | .100 | .054-.146 | .156 | .100-.212 | .128 | .084-.171 | .181 | .143-.220 | |

| T-S+ | .123 | .090-.156 | .102 | .067-.137 | .139 | .108-.171 | .142 | .100-.184 | |

| T-S- | .144 | .044-.243 | .127 | .061-.194 | .180 | .114-.246 | .108 | .080-.136 | |

| Oulu | All | .113 | .064-.162 | .114 | .060-.168 | .121 | .092-.150 | .158 | .117-.199 |

| T+S+ | - | - | - | - | - | - | .110 | .042-.179 | |

| T+S- | - | - | - | - | .145 | .060-.229 | .146 | .055-.237 | |

| T-S+ | .123 | .037-.208 | .152 | .013-.291 | .104 | .038-.171 | .21 | .139-.280 | |

| T-S- | - | - | - | - | .065 | .002-.129 | .138 | .039-.237 | |

Daily mean of suicide mortality during one month period before (-1 m), and after (+1 m) the switch into daylight saving time.

* = DST was not in use in Finland

m = daily mean of suicide mortality

CI = confidence interval of the mean

Table 7.

Women: Daily mean of suicide mortality and switching into daylight saving time in spring.

| Location | Days | 1969-80 * | 1981-2003(DST1 + DST2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1 m | +1 m | -1 m | +1 m | ||||||

| m | CI | m | CI | m | CI | m | CI | ||

| Finland | All | .024 | .020-.028 | .026 | .023-.029 | .027 | .024-.030 | .030 | .027-.033 |

| Helsinki | All | .055 | .048-.062 | .043 | .031-.055 | .043 | .034-.052 | .049 | .040-.059 |

| T+S+ | .042 | .014-.071 | .052 | .020-.083 | .047 | .019-.076 | .055 | .035-.076 | |

| T+S- | .054 | .028-.080 | .031 | .010-.052 | .024 | .012-.037 | .046 | .030-.062 | |

| T-S+ | .061 | .041-.081 | .029 | .004-.053 | .040 | .022-.057 | .065 | .028-.101 | |

| T-S- | .052 | .018-.087 | - | - | .049 | .020-.079 | .044 | .024-.065 | |

| Oulu | All | .033 | .006-.059 | .048 | .016-.080 | .048 | .030-.066 | .030 | .009-.050 |

| T+S+ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| T+S- | - | - | - | - | .053 | .013-.094 | - | - | |

| T-S+ | - | - | - | - | .067 | .018-.117 | - | - | |

| T-S- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

Daily mean of suicide mortality during one month period before (-1 m), and after (+1 m) the switch into daylight saving time.

* = DST was not in use in Finland

m = daily mean of suicide mortality

CI = confidence interval of the mean

Table 8.

Men: Daily mean of suicide mortality, and switching away from daylight saving time in fall.

| Location | Days | 1969-80* | 1981-94 (DST1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1 m | +1 m | -1 m | +1 m | ||||||

| m | CI | m | CI | m | CI | m | CI | ||

| Finland | All | .111 | .099-.122 | .101 | .094-.108 | .119 | .109-.128 | .120 | .112-.128 |

| Helsinki | All | .141 | .106-.177 | .120 | .104-.137 | .139 | .125-.153 | .140 | .122-.158 |

| T+S+ | .151 | .064-.238 | .115 | .078-.151 | .091 | .039-.143 | .163 | .107-.219 | |

| T+S- | .156 | .076-.236 | .107 | .048-.166 | .124 | .087-.161 | .123 | .079-.167 | |

| T-S+ | .137 | .089-.185 | .132 | .083-.182 | .156 | .115-.197 | .144 | .107-.180 | |

| T-S- | .138 | .087-.189 | .147 | .085-.208 | .184 | .125-.244 | .155 | .062-.248 | |

| Oulu | All | .114 | .060-.168 | .125 | .092-.158 | .239 | .165-.313 | .121 | .067-.175 |

| T+S+ | - | - | - | - | .324 | .113-.535 | - | - | |

| T+S- | .100 | .001-.200 | .107 | .002-.211 | .256 | .053-.458 | .110 | .000-.220 | |

| T-S+ | .189 | .084-.295 | .130 | .024-.237 | .182 | .060-.303 | .103 | .029-.176 | |

| T-S- | - | - | - | - | .267 | .142-.392 | .229 | .065-.393 | |

Daily mean of suicide mortality during one month period before (-1 m), and after (+1 m) the switch away daylight saving time.

* = DST was not in use in Finland

m = daily mean of suicide mortality

CI = confidence interval of the mean

Table 9.

Women: Daily mean of suicide mortality, and switching away from daylight saving time in fall.

| Location | Days | 1969-80 * | 1981-94 (DST1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1 m | +1 m | -1 m | +1 m | |||||||

| m | CI | m | CI | m | CI | m | CI | |||

| Finland | All | .028 | .025-.032 | .029 | .026-.033 | .029 | .024-.033 | .035 | .031-.039 | |

| Helsinki | All | .052 | .039-.064 | .048 | .033-.062 | .046 | .030-.061 | .064 | .049-.078 | |

| T+ | S+ | .071 | .045-.097 | .039 | .019-.058 | - | - | .074 | .040-.108 | |

| S- | - | - | .069 | .033-.104 | .049 | .015-.084 | .058 | .033-.083 | ||

| T- | S+ | .049 | .025-.073 | .055 | .021-.089 | .052 | .031-.073 | .067 | .038-.096 | |

| S- | .070 | .022-.118 | .023 | .001-.046 | .032 | .005-.059 | .065 | .026-.103 | ||

| Oulu | All | .033 | .011-.055 | .043 | .006-.081 | .020 | .001-.040 | .024 | .001-.047 | |

| T+S+ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| T+S- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| T-S+ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| T-S- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

Daily mean of suicide mortality during one month period before (-1 m), and after (+1 m) the switch away daylight saving time.

* = DST was not in use in Finland

m = daily mean of suicide mortality

CI = confidence interval of the mean

Table 10.

Men: Daily mean of suicide mortality, and switching away from daylight saving time in fall.

| Location | Days | 1969-80* | 1995-2003 (DST2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1 m | +1 m | -1 m | +1 m | ||||||

| m | CI | m | CI | m | CI | m | CI | ||

| Finland | All | .101 | .094-.108 | .101 | .093-.110 | .105 | .095-.115 | .097 | .088-.105 |

| Helsinki | All | .126 | .108-.145 | .140 | .119-.161 | .118 | .079-.157 | .106 | .090-.121 |

| T+S+ | .116 | .073-.159 | .181 | .078-.285 | .128 | .045-.212 | .080 | .033-.128 | |

| T+S- | .134 | .085-.182 | .072 | .017-.127 | .117 | .059-.176 | .109 | .075-.142 | |

| T-S+ | .135 | .079-.191 | .177 | .105-.249 | .112 | .071-.153 | .093 | .054-.131 | |

| T-S- | .152 | .072-.233 | .204 | .093-.314 | .099 | .035-.163 | .104 | .066-.142 | |

| Oulu | All | .131 | .089-.173 | .106 | .058-.154 | .145 | .096-.195 | .169 | .107-.230 |

| T+S+ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| T+S- | .104 | .003-.205 | - | - | .200 | .069-.332 | - | - | |

| T-S+ | .167 | .050-.284 | .085 | .001-.169 | - | - | - | - | |

| T-S- | - | - | - | - | .148 | .006-.290 | - | - | |

Daily mean of suicide mortality during one month period before (-1 m), and after (+1 m) the switch away daylight saving time.

* = DST was not in use in Finland

m = daily mean of suicide mortality

CI = confidence interval of the mean

Table 11.

Women: Daily mean of suicide mortality, and switching away from daylight saving time in fall.

| Location | Days | 1969-80 * | 1995-2003 (DST2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1 m | +1 m | -1 m | +1 m | ||||||

| m | CI | m | CI | m | CI | m | CI | ||

| Finland | All | .029 | .026-.032 | .025 | .022-.029 | .032 | .026-.038 | .027 | .022-.032 |

| Helsinki | All | .044 | .029-.058 | .042 | .033-.051 | .054 | .039-.070 | .035 | .026-.044 |

| T+S+ | .032 | .011-.052 | .058 | .019-.097 | .104 | .050-.159 | .053 | .002-.104 | |

| T+S- | .055 | .027-.083 | .074 | .036-.112 | .049 | .015-.083 | - | - | |

| T-S+ | .046 | .015-.076 | .032 | .010-.054 | .034 | .002-.067 | .040 | .016-.065 | |

| T-S- | .026 | .001-.051 | - | - | .064 | .030-.099 | - | - | |

| Oulu | All | .038 | .005-.072 | .032 | .010-.054 | .027 | .004-.051 | .051 | .012-.090 |

| T+S+ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| T+S- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| T-S+ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| T-S- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

Daily mean of suicide mortality during one month period before (-1 m), and after (+1 m) the switch away daylight saving time.

* = DST was not in use in Finland

m = daily mean of suicide mortality

CI = confidence interval of the mean

The 95% CIs of the daily mean values, controlled for the length of a period of study and the male and female population sizes in a region of study, were used to evaluate the statistical significance, so that if they did not overlap with each other, it was judged to indicate a marked statistical significance.

Results

In Finland, during the years 1969 to 2003, the daily mean of suicide mortality was at the highest, with a statistical significance, for both men (mean = .124, CI = .118-.129) and women (mean = .032, CI = .030-.033), during the period Y1, i.e. from May 14th to July 25th , as compared to the nationwide references (Table 4).

Local photoperiod

The highest daily mean of suicide mortality seem to have emerged later in Oulu compared with Helsinki, but only for men. Therefore, the results of men are reported here in more detail. The daily mean of suicide mortality was at the highest during the period Y1 in Helsinki (mean = .142, CI = .130-.154, Table 4), but during the period X2 i.e. from July 26th to November 3rd in Oulu (mean = .150, CI = .131-.169, Table 4). The same postponed pattern was found also when the time pattern of suicide mortality was evaluated by seasons. The daily mean of suicide mortality was highest in Helsinki during spring (mean = .138, CI = .128-.148), but during summer in Oulu (mean = .159, CI = .138-.180). Furthermore, a similar postponed pattern was seen from A1 (Helsinki) to D1 (Oulu) periods (Table 5). However, these results did not reach statistical significance.

Local daily weather changes

For men, the days with T+S+ seem to have had the highest daily mean of suicide mortality both in Helsinki, during the period Y1 (mean = .149, CI = .131-.167), and in Oulu, during the period X2 (mean = .206, CI = .122-.290), which were the most "dangerous" periods in these cities. However, when estimated by the 95% confidence intervals, there was no statistical difference in the variation of means of suicide mortality between the four types of weather changes. The daily mean of suicide mortality in Helsinki and Oulu, however, do exceed the nationwide daily means of suicide mortality (mean = .124 for Y1 in Finland, and mean = .112 for X2 in Finland), as do all the underlined values for different types of weather changes in Helsinki and Oulu compared with each period at issue in Tables 3, 4, and 5.

Daylight saving time

The use or timing of daylight saving time did not have a significant effect on the suicide mortality (Tables 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11).

Discussion

Nationwide results

Our key finding of statistical significance demonstrates the increased suicide mortality on nationwide level in Finland during the period from May 14th to July 25th. This 76-day period covers symmetrically both sides of summer solstice (Figure 1). During this period there is only 1 to 4 hours of darkness during the night in Helsinki but no darkness at all in Oulu. For the photoperiod dynamics in these locations, see http://www.gaisma.com/en/location/helsinki.html and http://www.gaisma.com/en/location/oulu.html, whose sunrise and sunset calculations are based on the algorithms displayed on National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Surface Radiation Research Branch web site at http://esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/grad/solcalc/calcdetails.html, and e.g. for latitudes less than 72° north and south, accuracy is approximately one minute. It is of note here that the photoperiod in Finland due to its time zone is asymmetrical throughout the year, the period of daylight being always shorter for the a.m. hours than it is for the p.m. hours. This phenomenon influences the mechanisms that decode the duration of the melatonin signal in the melatonin-target tissues.

From the circadian-clock point of view, this period (May 14th to July 25th) is a challenge to alignment of the circadian rhythms with the sleep-wake cycle, and it resembles "the critical spring photoperiodic window" on intermediate to long days that has been characterized in sheep [37]. Some possible biological mechanisms for our current finding are briefly discussed in the following. The very long day (20 to 24 hours of daylight) might challenge the network within the circadian pacemaker that is comprised of the so-called evening and morning active cells, and that takes part in the seasonal adaptation in diurnal animals such as fruit flies [38,39] and sheep [37,40-42]. If this holds for humans as well, it is not known at the moment. If it does, it could mean that, when day lengths approximate fall and winter, the morning active cells dominate the circadian output, e.g. the sleep-wake behavior. This dominance of hierarchy is gradually transferred to the evening active cells as the days get longer in spring [38,39], the coincidence effect of the morning and evening active cells disappearing when the melatonin signal duration becomes insufficient to sensitize adenylate cyclase and to support a peak expression of the morning-active cells [37]. Interestingly, the speeding up of the evening active cells (e.g. by sunshine) makes the morning active cells run faster in long (summer) but not in short (winter) days [38]. In Finland, which is located at high to temperate latitudes with the light-dark transitions being most rapid around equinoxes, the asymmetrical photoperiod possibly favors the evening-active cells, and produces pronounced melatonin-dependent effects on gene expression during spring and fall. Whether such "locked morning active cells" contribute to the peak in deaths from suicide in spring in particular is not known. However, CRY2 and PER2 genetic variants, which might influence the evening and morning signals from the circadian pacemaker system, associate with depression vulnerability [43,44] in humans. Therefore, depressed individuals in particular might suffer from entrainment errors during periods that challenge the circadian pacemaker and predispose to circadian misalignment.

Local daily weather changes

The complexity of the circadian pacemaker system suggests that signals other than the seasonal changes in photoperiod, such as temporary variations in local weather conditions, are likely to play a role in the entrainment process [35,45]. Our finding of the later suicide peak in the northern area of study, Oulu-region, supports this. However, the daily mean of suicide mortality was almost as high also during the Y1 period in Oulu, as in Helsinki.

Hereafter we discuss the potential influence of daily weather changes for the suicide mortality in Helsinki and Oulu during the peak periods.

During the most dangerous periods, Y1 in Helsinki and X2 in Oulu, days with T+S+ seemed to be the worst for suicide mortality. From the circadian point of view the long daylight combined with the daily increase in ambient temperature and sunshine hours (T+S+) may have further phase advanced the circadian rhythm of the male suicide victims. An increase in sunshine hours and exposure to light may accelerate and advance the phase of the principal circadian clock, but an increase in ambient temperature and exposure to heat may have a similar effect [46]. The peaks of suicides have associated with ambient temperature in earlier studies [47-49], but so far, to our knowledge, the role of the circadian clocks has not been addressed.

Many lines of evidence suggest that abnormalities in the thermoregulatory processes are common among the depressed and therefore may cause or maintain the circadian misalignment. Patients with a major depressive episode tend to have elevated body temperature throughout the night, not during the day, and a phase advance of the circadian rhythm of core body temperature [18]. As hot nights might advance the phase of the circadian clock [50], and nocturnal body temperature during rapid-eye-movement sleep is influenced by hot, not cold, ambience [51], the dynamics of nocturnal temperatures might contribute to the advanced and rather fixed phase positions of circadian rhythms in major depressive episodes. In addition, sleep abnormalities, characteristically excessive rapid-eye-movement sleep at the cost of slow-wave sleep [17], are likely to give an abnormal (accelerating) feedback to the principal circadian pacemaker [26]. Further, during winter the duration of rapid-eye-movement sleep per night tends to increase [52], giving no support to deceleration and thereby favoring the desynchronization that may result in lowered mood and the subsequent increase in risk of suicide.

Daily fluctuations in temperature may play a part in the timing of suicides, either in combination with the long day length, or possibly also as a separate stressor. Studies concerning the over-activity in the functions of brown adipose tissue among the depressed [53] are most interesting in this respect, since the over-activity of brown adipose tissue may lead to reduced adaptation to rapid changes in ambient temperature that are typical during spring and fall. Once being activated, brown adipose tissue does not become quiescent easily [54], and if having been over-activated, it may through the thermoregulatory defect lead to disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and appetite control, and lead to early morning awakenings and loss of weight of the affected individual. Whether this kind of "vernalization failure" characterizes a suicide process and contributes to a mortality peak year after year is not known, but needs experimental data for analysis. However, in line with this background, for the Y1 period the daily mean of suicide mortality of men was at its lowest during the days of T-S- in Helsinki (mean = .124, CI = .106-.142, Table 4) and during the days of T-S+ in Oulu (mean = .140, CI = .090-.190, Table 4), suggesting that T- is a common nominator for the "safer" weather changes in both locations. T-S+ days were the "safest" also during the X2 period in Oulu. The daily decrease in temperature could therefore serve as a protective change during otherwise warm season. However, as the daily means did not differ significantly between the four types of weather changes, this is somewhat speculative thus far.

Limitations

Our limitation here is that we did not have the diagnostic information of the suicide victims, and that we demonstrate associations only, which do not necessarily tell anything about causality. Another limitation is that we did not have access to a suitable method, e.g. molecular-timetable methods [55] to be applied to a range of tissues, such as the brain and brown adipose tissue, from autopsy studies, to be able to analyze a mechanism of action and thereby to demonstrate a potential link between abnormalities in the circadian pacemaker system and death from suicide. On the other hand, our strengths include the nationwide sample of suicides for a long period of time, from a country with a high suicide mortality rate.

Conclusions

Our main findings here are that suicide mortality is higher during summer months and that daily changes in sunshine and ambient temperature are likely to modify the suicide mortality. Our findings presented herein now wait for tests by others in independent materials and is thus open to replication and the subsequent verification or falsification of the hypothesis. Some experimental data would be urgently needed for explanation of the mechanisms of action that take place in the brain of depressed patients and predispose them to suicide within those particular periods of time that we identified here. Suicide is a long process, whereas the timing of death from suicide appears far from random. In Finland from 1969 to2003 suicide mortality was elevated from May 15th to July 25th. This phenomenon should be considered also in clinical practice, since it bears implications for suicide prevention.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Authors TP and KS designed the study and wrote the protocol. Author JL conceived and took part in designing the study. Authors LH and TP managed the literature searches and analyses and author LH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Laura Hiltunen, Email: laura.hiltunen@thl.fi.

Kirsi Suominen, Email: kirsi.suominen@hus.fi.

Jouko Lönnqvist, Email: jouko.lonnqvist@thl.fi.

Timo Partonen, Email: timo.partonen@thl.fi.

Acknowledgements and funding

We thank Professor (Emeritus) of Mathematics Seppo Mustonen, PhD, University of Helsinki, Docent of Astronomy Heikki Oja, PhD, Almanac Office at the University of Helsinki, and the meteorologists Anneli Nordlund and Seppo Sarkkula at the Finnish Meteorological Institute, all in Helsinki, Finland, for their help in data processing.

The Finnish Cultural Foundation, Finnish National Graduate School for Clinical Investigation, and Finnish Graduate School of Psychiatry allocated scholarships (to LH) for this project but had no further role in study design.

References

- Ajdacic-Gross V, Lauber C, Sansossio R, Bopp M, Eich D, Gostynski M, Gutzwiller F, Rossler W. Seasonal associations between weather conditions and suicide--evidence against a classic hypothesis. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(5):561–569. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajdacic-Gross V, Bopp M, Ring M, Gutzwiller F, Rossler W. Seasonality in suicide--a review and search of new concepts for explaining the heterogeneous phenomena. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(4):657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partonen T, Haukka J, Nevanlinna H, Lonnqvist J. Analysis of the seasonal pattern in suicide. J Affect Disord. 2004;81(2):133–139. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00137-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock D, Greenberg DM, Hallmayer JF. Increasing seasonality of suicide in Australia 1970-1999. Psychiatry Res. 2003;120(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(03)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonda T, Bozsonyi K, Veres E. Seasonal fluctuation of suicide in Hungary between 1970-2000. Arch Suicide Res. 2005;9(1):77–85. doi: 10.1080/13811110590512967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakko H, Rasanen P, Tiihonen J. Seasonal variation in suicide occurrence in Finland. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;98(2):92–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayha S. Autumn incidence of suicides re-examined: data from Finland by sex, age and occupation. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;141:512–517. doi: 10.1192/bjp.141.5.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haukka J, Suominen K, Partonen T, Lonnqvist J. Determinants and outcomes of serious attempted suicide: a nationwide study in Finland, 1996-2003. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(10):1155–1163. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges FS, Yip PS, Yang KC. Seasonal changes in suicide in the United States, 1971 to 2000. Percept Mot Skills. 2005;100(3 Pt 2):920–924. doi: 10.2466/pms.100.3c.920-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew KS, McCleary R. The spring peak in suicides: a cross-national analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(2):223–230. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)E0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkkilä S Lapsi-itsemurhista Suomessa v.1885-1934 Lääketieteellinen aikakauskirja Duodecim 19375536–548.21941658

- Saelan T. Om Slefmordet i Finland i statistiskt och rättmedicinskt afseende. Academisk afhandling. Helsinki, Finland: Kejserliga Alexanders-Universitetet; 1864. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Marttunen MJ, Heikkinen ME, Isometsa ET, Kuoppasalmi KI, Lonnqvist JK. Mental disorders and comorbidity in suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(6):935–940. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:205–228. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reutfors J, Osby U, Ekbom A, Nordstrom P, Jokinen J, Papadopoulos FC. Seasonality of suicide in Sweden: relationship with psychiatric disorder. J Affect Disord. 2009;119(1-3):59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postolache TT, Mortensen PB, Tonelli LH, Jiao X, Frangakis C, Soriano JJ, Qin P. Seasonal spring peaks of suicide in victims with and without prior history of hospitalization for mood disorders. J Affect Disord. 2010;121(1-2):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain A, Kupfer DJ. Circadian rhythm disturbances in depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(7):571–585. doi: 10.1002/hup.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone P, Maj M. The circadian basis of mood disorders: recent developments and treatment implications. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18(10):701–711. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souetre E, Salvati E, Candito M, Darcourt G. Biological clocks in depression: phase-shift experiments revisited. Eur Psychiatry. 1991. 21-22-29.

- Kripke DF, Nievergelt CM, Joo E, Shekhtman T, Kelsoe JR. Circadian polymorphisms associated with affective disorders. J Circadian Rhythms. 2009;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1740-3391-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund A, Kovanen L, Saarikoski ST, Haukka J, Reunanen A, Aromaa A, Lonnqvist J, Partonen T. NPAS2 and PER2 are linked to risk factors of the metabolic syndrome. J Circadian Rhythms. 2009;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1740-3391-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partonen T, Haukka J, Pirkola S, Isometsa E, Lonnqvist J. Time patterns and seasonal mismatch in suicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109(2):110–115. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690X.2003.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonnqvist J. In: Oxford Textbook of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention A Global Perspective. Wasserman D, Wasserman C, editor. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. Suicide prevention in Finland. 793-794-795. [Google Scholar]

- Partonen T, Pulkkinen E, Pirkola S, Isometsa E, Lonnqvist J. Timekeeping in death from suicide. The Royal College of Psychiatrists Annual Meeting Summer 2000 Edinburgh Abstarcts. 2000;121 [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht U. Circadian clocks in mood-related behaviors. Ann Med. 2010;42(4):241–251. doi: 10.3109/07853891003677432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deboer T, Vansteensel MJ, Detari L, Meijer JH. Sleep states alter activity of suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(10):1086–1090. doi: 10.1038/nn1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster RG, Roenneberg T. Human responses to the geophysical daily, annual and lunar cycles. Curr Biol. 2008;18(17):R784–R794. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roenneberg T, Kumar CJ, Merrow M. The human circadian clock entrains to sun time. Curr Biol. 2007;17(2):R44–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JF, Kronauer RE, Czeisler CA. Phase-shifting human circadian rhythms: influence of sleep timing, social contact and light exposure. J Physiol. 1996;495(Pt 1):289–297. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monecke S, Saboureau M, Malan A, Bonn D, Masson-Pevet M, Pevet P. Circannual phase response curves to short and long photoperiod in the European hamster. J Biol Rhythms. 2009;24(5):413–426. doi: 10.1177/0748730409344502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderLeest HT, Houben T, Michel S, Deboer T, Albus H, Vansteensel MJ, Block GD, Meijer JH. Seasonal encoding by the circadian pacemaker of the SCN. Curr Biol. 2007;17(5):468–473. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman MA, Swaab DF. Diurnal and seasonal rhythms of neuronal activity in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of humans. J Biol Rhythms. 1993;8(4):283–295. doi: 10.1177/074873049300800402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewy AJ, Lefler BJ, Emens JS, Bauer VK. The circadian basis of winter depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(19):7414–7419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602425103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooley JJ. Treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders with light. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37(8):669–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troein C, Locke JC, Turner MS, Millar AJ. Weather and seasons together demand complex biological clocks. Curr Biol. 2009;19(22):1961–1964. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruuhela R, Hiltunen L, Venalainen A, Pirinen P, Partonen T. Climate impact on suicide rates in Finland from 1971 to 2003. Int J Biometeorol. 2009;53(2):167–175. doi: 10.1007/s00484-008-0200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GC, Johnston JD, Clarke IJ, Lincoln GA, Hazlerigg DG. Redefining the limits of day length responsiveness in a seasonal mammal. Endocrinology. 2008;149(1):32–39. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoleru D, Nawathean P, Fernandez MP, Menet JS, Ceriani MF, Rosbash M. The Drosophila circadian network is a seasonal timer. Cell. 2007;129(1):207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi E, Sugino K, Kula E, Okazaki E, Tachibana T, Nelson S, Rosbash M. Dissecting differential gene expression within the circadian neuronal circuit of Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(1):60–68. doi: 10.1038/nn.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BA, Martin AM, Furney P, Elliott JA. Absence of a serum melatonin rhythm under acutely extended darkness in the horse. J Circadian Rhythms. 2011;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1740-3391-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazlerigg DG, Andersson H, Johnston JD, Lincoln G. Molecular characterization of the long-day response in the Soay sheep, a seasonal mammal. Curr Biol. 2004;14(4):334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln GA, Andersson H, Hazlerigg D. Clock genes and the long-term regulation of prolactin secretion: evidence for a photoperiod/circannual timer in the pars tuberalis. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15(4):390–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavebratt C, Sjoholm LK, Soronen P, Paunio T, Vawter MP, Bunney WE, Adolfsson R, Forsell Y, Wu JC, Kelsoe JR, Partonen T, Schalling M. CRY2 is associated with depression. PLoS One. 2010;5(2):e9407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavebratt C, Sjoholm LK, Partonen T, Schalling M, Forsell Y. PER2 variantion is associated with depression vulnerability. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sehadova H, Glaser FT, Gentile C, Simoni A, Giesecke A, Albert JT, Stanewsky R. Temperature entrainment of Drosophila's circadian clock involves the gene nocte and signaling from peripheral sensory tissues to the brain. Neuron. 2009;64(2):251–266. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhr ED, Yoo SH, Takahashi JS. Temperature as a universal resetting cue for mammalian circadian oscillators. Science. 2010;330(6002):379–385. doi: 10.1126/science.1195262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti A, Lentini G, Maugeri M. Global warming possibly linked to an enhanced risk of suicide: data from Italy, 1974-2003. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HC, Lin HC, Tsai SY, Li CY, Chen CC, Huang CC. Suicide rates and the association with climate: a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2006;92(2-3):221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, De Meyer F, Thompson P, Peeters D, Cosyns P. Synchronized annual rhythms in violent suicide rate, ambient temperature and the light-dark span. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90(5):391–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Zumbrunn G, Fleury-Olela F, Preitner N, Schibler U. Rhythms of mammalian body temperature can sustain peripheral circadian clocks. Curr Biol. 2002;12(18):1574–1583. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashizume Y. Fluctuations of rectal and tympanic temperatures with changes of ambient temperature during night sleep. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;51(3):129–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1997.tb02374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohsaka M, Fukuda N, Honma K, Honma S, Morita N. Seasonality in human sleep. Experientia. 1992;48(3):231–233. doi: 10.1007/BF01930461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen P, Kortelainen ML. Long-term alcohol consumption and brown adipose tissue in man. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1990;60(6):418–424. doi: 10.1007/BF00705030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zukotynski KA, Fahey FH, Laffin S, Davis R, Treves ST, Grant FD, Drubach LA. Seasonal variation in the effect of constant ambient temperature of 24 degrees C in reducing FDG uptake by brown adipose tissue in children. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37(10):1854–1860. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1485-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda HR, Chen W, Minami Y, Honma S, Honma K, Iino M, Hashimoto S. Molecular-timetable methods for detection of body time and rhythm disorders from single-time-point genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(31):11227–11232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401882101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]