Review on mouse and human lung dendritic cells and their role in controlling T-cell activation and tolerance to inhaled antigens.

Keywords: asthma, alveolar macrophage, antigen processing

Abstract

This review updates the basic biology of lung DCs and their functions. Lung DCs have taken center stage as cellular therapeutic targets in new vaccine strategies for the treatment of diverse human disorders, including asthma, allergic lung inflammation, lung cancer, and infectious lung disease. The anatomical distribution of lung DCs, as well as the division of labor between their subsets, aids their ability to recognize and endocytose foreign substances and to process antigens. DCs can induce tolerance in or activate naïve T cells, making lung DCs well-suited to their role as lung sentinels. Lung DCs serve as a functional signaling/sensing unit to maintain lung homeostasis and orchestrate host responses to benign and harmful foreign substances.

Introduction

Tissue histiocytes (fixed tissue macrophages) were recognized for their ability to clear materials from the blood, giving rise to the concept of the reticuloendothelial system [1]. Improved characterization of these cells led to the idea of a MPS arising from common bone marrow-derived blood-borne progenitors [2], including monocytes, macrophages, and other cells [3]. In 1965, Volkman and Gowans [4] demonstrated that bone marrow-derived peripheral blood monocytes differentiate into macrophages, ending a longstanding notion that lymphocytes were the immediate precursors of macrophages, and in 1973, Steinman and Cohn [5] characterized and named DCs in mouse spleen. The term “dendritic cell” was deemed appropriate based on morphologic observations of living cells in vitro. The MPS represents a diverse—functionally and phenotypically—heterogeneous system of cells distributed throughout the body [6]. Early studies about the structure and function of the MPS did not fully appreciate the extensive network of lung DCs [7]. In this review, we show how, through its interaction with inhaled substances, which activate DCs for the induction of tolerance or an acquired immune response, the lung DC network serves to maintain lung function and homeostasis [8]. One of the “hallmarks” of DCs is their ability to serve as APCs, which are not a distinct cell type. Rather, antigen presentation is a functional capacity shared by many cell types including basophils [9–11], eosinophils [12], macrophages [13], B cells [14, 15], and human endothelial cells [16–19]. DCs are often considered the predominant APC type as a result of their essential roles in immune responses, and based on this ability, lung DCs can be viewed as interposed at the interface between innate and acquired immunity. DCs fulfill an essential role in lung homeostasis, in host resistance to infection and cancer, and in the pathogenesis of pulmonary diseases. In this review, we will discuss the three main categories of lung tissue DCs, namely pDCs, cDCs, and DCs arising in inflammatory conditions.

ANATOMICAL DISTRIBUTION OF LUNG DCs

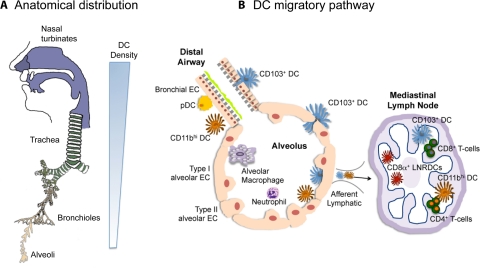

DCs perform their essential role in defense of the lung based on their anatomical location that creates a functional cellular interface between the external environment and the internal lung microenvironment. As illustrated in Fig. 1, lung DCs are in intimate contact with the respiratory epithelium of the nose, nasopharynx, trachea, large and small bronchi and bronchioles, and the alveolar interstitium [20–23]. Throughout the respiratory mucosa and in the alveoli, DCs “snorkel” through the epithelial-tight junctions, sending their extended dendritic projections into the airway lumen, where they come in contact with antigens [24, 25]. Studies with rodents established the extensive network of DCs throughout the respiratory mucosa [26, 27]. In newborn rats, DCs first appear at the base of nasal turbinates, an anatomical site where most inhaled particles are first encountered in the respiratory tract. During the next few days of postnatal development, DC numbers increase steadily in the lung parenchyma [27, 28]. Large numbers of DCs are associated with the large airways and to a lesser extent, the smaller airways, whereas DCs occur in smaller numbers in the alveoli. The airway DC population turns over rapidly in vivo, with a half-life of ≤2 days [29, 30]. In contrast, the alveolar lumen is dominated by resident AMs [29, 31].

Figure 1. Anatomical location and migratory pathway of lung DCs.

(A) DCs are located throughout the respiratory tract. They are most abundant in the nose, nasal turbinates, and trachea. As shown by the sliding scale at right, the density of lung DCs declines as one descends the respiratory tract. (B) Two subsets of cDCs are present: an intraepithelial web of CD103+ cDCs (blue) and CD11bhi cDCs (orange) in the lamina propria, together with pDCs (yellow). The alveoli are lined with type I and type II alveolar ECs (peach). AMs (purple) form the main population of resident alveolar cells, whereas neutrophils can be recruited in response to inflammatory stimulation. Both cDC subsets are present in the alveoli and migrate to the draining LNs (right), where they present antigens to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. CD103+ cDCs are specialized in cross-priming as CD8α+ LNRDCs (red).

DC DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY

The origin and developmental pathways of lung DCs have been considerably clarified in recent years. Liu et al. [32], for the first time, showed that an early progenitor, termed the myeloid progenitor, develops into the MDP in the bone marrow. The MDP develops into the common DC precursor and into monocytes. The common DC precursor develops into pre-cDCs and into pDCs. This finding shows that monocytes and the common DC precursor diverge from the MDP in the bone marrow and clarifies the origins of monocytes, cDCs, and pDCs. Whether these relationships among monocyte and DC progenitors also occur in humans is, as yet, undetermined. Thus, bone marrow-derived mononuclear phagocytes present in the peripheral blood, including monocytes and pDCs, replenish the lung DC subsets on a daily basis, and the entire lung DC population is renewed in about 1 week [30, 31]. Under steady-state conditions, “patrolling” blood monocyte subsets in the lung vasculature are situated such that within minutes to hours after an inflammatory stimulation, they leave the blood vessel lumen, cross the endothelial barrier, and traffic into sites of inflammation, where given the appropriate signals, they are able to differentiate into inflammatory DCs [33].

DC MATURATION, ACTIVATION, AND TRAFFICKING

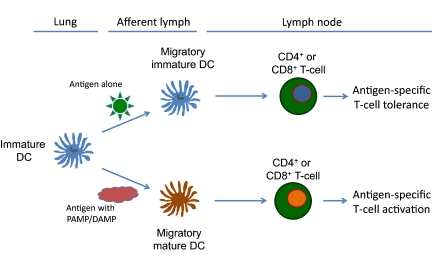

Lung DCs live in an “immature” state, in which they exhibit an enhanced ability to recognize and capture inhaled materials, principally through receptor-mediated endocytic processes. As illustrated in Fig. 2, DCs that have captured inhaled materials undergo a maturation process, leave the lung, and migrate to draining regional lymphoid tissues, where they are capable of fully activating naïve T cells for the expression of acquired immunity [34]. When the ingested substances do not contain the full complement of appropriate signals needed to initiate DC maturation, these DCs remain in an immature state and fail to fully activate naïve T cells for acquired immunity. Rather, they are able to induce immunologic tolerance in naïve T cells. This dual pathway for the activation of naïve T cells is a critical aspect of lung DC biology and a continuous process that occurs with every breath. These important characteristics of DCs led to the discovery of functional heterogeneity among a variety of lung DC subsets [35–38]. The close, functional relationship among DC populations, resident AMs, and lung ECs maintains lung homeostasis, regulates inflammation and innate and acquired immune responses, and down-regulates these responses, returning the lung to its normal steady state [7, 39, 40].

Figure 2. Antigen-induced T cell tolerance or antigen-induced T cell activation is controlled by the nature of the inhaled antigen.

In the absence of second signals provided by PAMPs or host endogenous DAMPs, antigen-exposure DCs migrate to the regional draining LNs and promote T cell tolerance (upper pathway). In the presence of PAMPs or DAMPs, antigen-exposed DCs mature and up-regulate cell-surface costimulatory molecules, migrate to regional LNs, and promote antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation.

Two signals are required to fully activate the DC maturation program (Fig. 2) [41]. The first signal is derived principally through receptor-mediated antigen uptake, whereas the second signal is derived from recognition of antigen-associated molecules, termed PAMPs or DAMPs, derived from the host [34]. PAMPs/DAMPS are recognized by PRRs, expressed on the surface of lung DC subsets (reviewed in refs. [42–55]). DCs express surface and intracellular PRRs, such as TLRs, nucleotide-binding domain/leucine-rich repeat receptors, C-type lectin receptors (including the DC-specific lectin DC-SIGN), scavenger receptors, and a variety of other receptor molecules. Various DC subsets differ in the PRRs they express (Table 1). In contrast to other DC subsets, which express a broad profile of TLRs, the TLR profile in pDCs is restricted to the intracellular receptors TLR7 and TLR9. These differences define the types of PAMP and DAMP ligands capable of activating these distinct DC subsets. Pathogen recognition and the activation of immature DCs after antigen engulfment are not simple processes resulting from a single receptor system and a single microbial ligand or host ligand. Rather, PRRs often function in tandem and function synergistically with themselves [52, 53, 56] and other non-TLR innate receptors [54]. To add to the already growing complexity of DC maturation, PRRs have also been shown to function synergistically with other non-PRRs to generate effective immune responses [57–59]. Antigen plus PAMP-exposed immature DCs differentiate into mature DCs that express all three signals necessary for the activation of naïve T cells, i.e, MHC class II-antigenic peptide complexes derived from antigen processing; up-regulated, costimulatory molecules; and expression of high levels of appropriate cytokines needed to fully activate naïve T cells and polarize them into antigen-specific T effector phenotypes (Th1, Th2, Th17, Treg). Thus, the generation of an “optimal” acquired immune response depends on the ability of lung DCs to undergo a full maturation step, followed by their ability to induce the antigen-specific full maturation and differentiation of naïve T cells. Although incompletely understood, these essential steps depend, in turn, on the concerted actions of all of these receptors on lung DC subsets and naïve T cells, resulting in a T cell response that is most beneficial to the host.

Table 1. Cell Surface Markers, Activation Markers, and TLR Distribution for Mouse and Human Lung DC Subsets.

| DC subset | Surface markers | Activation markers | TLRs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Murine lung | |||

| CD103+ DCs | CD11c+, CD8α–, CD11blo/–, CD103+, MHC class II+, Langerin+ | MHC class II, CD80, CD83, CD86, PDL1, PDL2, CD40 | 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 11, 12, 13 |

| CD11bhi DCs | CD11c+, CD8α–, CD11bhi, CD103–, MHC class II+, Langerin– | MHC class II, CD80, CD83, CD86, PDL1, PDL2, CD40 | 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13 |

| pDCs | CD11cint, CD11blo/–, B220+, Ly6c+, MHC class II–/lo, SiglecH+ | MHC class II, CD80, CD86 | 7, 9, 12 |

| Human DCs | |||

| Myeloid DC in BALF, spleen, blood | CD11c+, BDCA1+, HLA-DR+, BDCA3+, BDCA4– | HLA-DR, CD80, CD86 | ? |

| Myeloid DC in blood and interstitium | CD11c+, BDCA3+, HLA-DR+, Clec9A (DNGR-1), Necl2+, Langerin+, CXCR1+ | HLA-DR, CD80, CD86 | 3 |

| pDCs | CD11cdim, BDCA2+, BDCA4+ CD123+, L-selectin+, IL-3R+, HLA-DR–/lo | HLA-DR, CD80, CD86 | 7, 9 |

In contrast to the initiation of adaptive T cell immunity, in the absence of PAMP/DAMPs, DCs fail to up-regulate costimulatory molecules, such as CD40, CD80, and CD86, and the cytokines needed to promote full activation of naïve T cells to express acquired immunity [34, 60–62]. Rather, they undergo an attenuated, proliferative response upon stimulation and differentiate into T cell subsets that promote antigen-specific tolerance [62]. Lung DCs are also cross-regulated by activated pDC and cDC subsets. For example, recent data suggest that pDCs may mediate tolerance to harmless antigens by directly dampening inflammatory responses induced following antigen uptake by cDCs [61].

A longstanding challenge to researchers has been how to discriminate between DCs that are at various stages of maturation/activation versus distinct DC subsets (typically assessed by phenotype). Under inflammatory conditions, monocytes migrate from the blood to the tissues, where they give rise to DCs and macrophages [63]. DC-like cells with distinct phenotypes are observed at inflammatory sites in mice and humans. For example, activated pDCs, which produce large amounts of IFN-α, and a monocyte-derived DC subset, termed TiPDC, which produces TNF-α and iNOS, are found in the tissues following infections [64, 65]. Although first identified in the spleens of Listeria monocytogenes-infected mice, TiPDCs have also been identified in the lungs of mice infected with influenza A virus [66]. Interestingly, TiPDCs may constitute the major infected cell type during chronic Leishmania infection [67]. Nevertheless, the relative importance of TiPDCs in the host response to lung pathogens remains to be determined. In this review, we use the term “inflammatory DC” to serve as a functional definition, rather than a phenotypic one, which can be assigned to one or more DC subsets. It is likely that TiPDCs and pDCs represent only some of the types of inflammatory DCs that can be generated in response to infection.

An integral feature of the maturation and activation of DCs discussed earlier is the homing of DC progenitor cells to the lung, the homeostatic retention of DCs within the lung, and the migration of activated DCs to the LNs. Furthermore, and depending on specifically how (and probably where) the DCs have been activated, these cells can “imprint” different effector mechanisms onto CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and alter their homing properties. Chemokines are key mediators of DC trafficking and retention. Although a thorough discussion of this extensive literature is beyond the scope of this review, a few key, recent findings are worth noting. Most chemokines are promiscuous, a feature that underlies the complexity of chemokine biology, in that their function is often redundant. The CCR6 is unique in this regard, in that it binds a single chemokine, CCL20, which is expressed by ECs in mucosal tissue, including the gut and lung (reviewed in Ito et al. [68]). CCR6 is expressed by immature DCs, B cells, and subsets of T cells (Th17 and Tregs). Kallal et al. [69] reported recently that CCR6 plays a key role in regulating the balance between pDC and cDC in the context of RSV infection in the lung. The chemokines and their receptors that mediate DC trafficking allergic inflammation are generally distinct from those that mediate DC trafficking in response to infection. Robays et al. [70] tracked and compared chemokine receptor knockout versus WT DC populations through various lung compartments. These investigators showed that CCR2, but not CCR5 or CCR6, directly controlled the accumulation of DCs into allergic lungs. Furthermore, the size of inflammatory monocyte populations in peripheral blood was strikingly CCR2-dependent, suggesting that CCR2 mediates the release of monocytic DC precursors into the bloodstream. Another striking finding relates to the CCRL2, a chemokine receptor expressed by activated DCs and macrophages, but not eosinophils and T cells. CCRL2-deficient mice show normal recruitment of circulating DCs into the lung but are defective in the trafficking of antigen-loaded lung DCs to mediastinal LNs [71]. This defect was associated with a reduction in LN cellularity and reduced priming of Th2 responses. The central role of CCRL2 deficiency in DCs was supported by the fact that adoptive transfer of CCRL2-deficient, antigen-loaded DCs into WT animals recapitulated the phenotype observed in the knockout mice. These data show a nonredundant role of CCRL2 in lung DC trafficking and in the control of excessive airway inflammatory responses. The findings described above underscore the complexity of the mechanisms that control DC trafficking in response to infection and inflammation.

MOUSE LUNG DCs

In the mouse, Ly-6Chi blood monocyte progenitors give rise to the Ly-6Chi and Ly-6Clo circulating monocyte subsets [72, 73]. Randolph and colleagues [63, 74] have shown that Ly-6Clo blood monocytes develop into CD11bhiCD103– lung DCs, whereas Ly-6Chi blood monocytes develop into the CD11b–CD103+ lung DCs. Using lysozyme M-Cre × Rosa26-stopflox EGFP mice to assess DC relationships with monocytes or other DC populations, Jakubzick et al. [74] showed that monocytes, which were EGFP+, developed into CD11bhi and CD103+ lung DCs during the steady state. Whether blood monocytes maintain human lung DC subsets in a similar manner has not been determined, but this is an important question to be answered, as it relates to the manipulation of key DC subsets and their precursors during inflammation and human lung disorders [63]. The development of pDCs in human and mouse has several similarities. For example, human and mouse pDCs express transcription factor 4 (E2-2), which is essential for maintaining the cell fate of mature pDCs through direct regulation of lineage-specific gene expression programs [75–77], as well as the Ets family transcription factor, Spi-B [77, 78].

Lymphoid and spleen DCs have been well-characterized in the mouse [36, 79, 80], and this has contributed significantly to the characterization of mouse lung DC subsets. As illustrated in Table 1, there are three major subsets of DCs in mouse lung in the normal steady state. CD103+ cDCs are associated with the single layer of respiratory ECs residing in the lung interstitium and arteriolar walls [81]. In this close association with ECs, CD103+ cDCs also express tight junction proteins, including claudin-1, claudin-7, and zona occludens-2, which anchor the cDCs within the EC layer [81, 82] and also allow snorkeling dendrites to extend through the airway EC barrier into the airway lumen. The second lung DC subset, CD11bhi DCs, is found in the airway and the lung parenchyma [23, 83, 84]. Along with CD103+DCs, CD11bhi DCs are able to migrate from the airways to regional mediastinal LNs. The third subset, pDCs, expresses CD11cdim, CD11b–, Ly6c+, B220+, and SiglecH+. Lung pDCs appear to be functionally specialized for their ability to capture and cross-present viral antigens and microbial components in the form of CpG DNA [85, 86]. In the steady state, immature lung DCs, which encounter the appropriate signals for activation, undergo maturation-associated loss of endocytic properties and up-regulation of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules and migrate to regional mediastinal LNs. Antigen processing-associated up-regulation of surface MHC class II molecules by lung DCs is coupled to enhanced cell motility and increased expression of surface chemokine receptor molecules. Thus, mature DCs are now able to migrate to draining regional LNs, bearing a full complement of MHC class II-antigenic peptide complexes, costimulatory molecules, and LN homing receptor molecules [87].

Murine pDCs secrete large amounts of type I IFN in the LNs in response to viral stimulation. These pDCs also act as tolerogenic cells when expressing the inducible tolerogenic enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, the inducible costimulator ligand, and/or the PDL1, which mediate Treg development and suppression of self- and alloreactive cells. The ability of pDCs to induce Treg development likely underlies their capacity to maintain immunological tolerance, limit inflammation, and restore homeostasis in the lung (reviewed in ref. [88]). It should be noted that the tolerogenic phenotype of pDCs is dependent on extrinsic factors. Bonnefoy et al. [89] reported recently that TGF-β-treated pDCs favor Th17, but not Treg, commitment. TGF-β-treated pDCs expressed TGF-β mRNA and released active TGF-β protein. Furthermore, an anti-TGF-β antibody blocked Th17 commitment. Unexpectedly, TGF-β treatment also induced IL-6 production by pDCs, which serves to further promote Th17 commitment driven by TGF-β-exposed pDCs. The in vivo pathogenic role of TGF-β-treated pDCs was confirmed in a Th17-dependent, collagen-induced arthritis model, in which the injection of TGF-β-treated pDCs significantly increased arthritis severity and pathogenic Th17 cell accumulation in the draining LNs.

Pre-DCs include pDCs and peripheral blood monocytes, which upon inflammatory stimulation, can be the direct precursors of inflammatory DCs. Pre-DCs do not have the “classic” dendritic form, and cDCs function but are able to differentiate into DC subsets in response to antigen uptake and host-derived inflammatory signals. In the mouse lung, inflammatory DCs are not particularly abundant in regional lymphoid tissues in the steady state. Peripheral blood monocytes circulating in the lung capillary bed infiltrate lung tissues rapidly during inflammation, where they differentiate into inflammatory DCs. Thus, mouse lung cDCs and pDCs and their pre-DC precursors reside within the lung parenchyma and the lung vascular bed, providing a formidable cellular system that defends the lung and maintains homeostasis [30].

DCs AT THE INNATE-ADAPTIVE IMMUNE INTERFACE

CD103+ DCs are implicated in antigenic transfer to draining regional LNs, where LN resident CD8α+ DCs capture antigen from CD103+ lung DCs [90–92]. Emigrant CD103+ lung DCs and the LN resident CD8α+ DCs are able to present antigen to and activate naïve CD8+ T cells [93]. The mechanism of antigenic transfer enhances the numbers of DCs capable of antigen presentation and activation of naïve T cells in draining regional LNs [92]. The mechanisms by which these LN resident CD8α+ DCs acquire antigen from emigrant lung CD103+ DCs are unknown and an area of intense current research. In the mouse, CD103+ DCs have been shown to be developmentally related to the CD8α+ LN resident CD8α+ DCs. Mice deficient in the transcription factor Batf3 are deficient in lung CD103+ DCs and LN resident CD8α+ DCs, and Batf3−/− mice exhibit reduced priming of CD8α+ T cells after Sendai virus infection, as well as increased pulmonary inflammation [94, 95]. This division of labor between the two major DC subsets of the mouse lung and their ability to process and transfer antigen among different DC subsets for the activation of naïve T cells may be dependent on the type of antigen encountered by the lung CD103+ DCs. For example, processing of antigens derived from harmless microbes versus pathogenic microbes may serve to maintain lung homeostasis rather than elicit an inflammatory and/or acquired immune response in the lung. This possibility remains an intense area of study and one that is critical for improving vaccines.

CD11bhi DCs migrate from the blood into the lung in response to Cryptococcus neoformans in a CCR2-dependent manner, and these cells are essential for clearance of the organism [96]. CCR2-dependent TiPDCs have been found in the spleens of L. monocytogenes-infected mice [64]. The accumulation of these specialized DC subsets in the lung has been confirmed using influenza A viruses, including H5N1 strains, and TiPDCs are required for the further proliferation of influenza-specific CD8+ T cells and ultimately, virus clearance [66]. McGill et al. [97] show that during influenza challenge, CD8α+ DCs can migrate and accumulate in the lung. Along with interstitial DCs and pDCs, these CD8α+ DCs are essential for interactions with CD8+ T cells to enable the development of adaptive immunity following influenza infection. Additionally, CD11c+CD11b+MHCII+ DCs have been shown to be essential for the maintenance of inducible bronchial-associated lymphoid tissue in response to influenza infection in mice [98]. Aspergillus fumigatis causes an influx of monocytes and monocyte-derived inflammatory DCs into the lungs, whereas depletion of these cells causes impaired pulmonary fungal clearance, as well as abolished CD4+ T cell priming [99]. During RSV infection, there is a massive influx of CD11bhi DCs and pDCs during the first 7 days, whereas CD103+ DCs disappear from the lung; yet, both major subsets transported RSV RNA to the lung draining regional LN [100]. In a mouse model of asthma, activated CD11c+ CD11bhi DCs accumulate after OVA challenge in OVA-sensitized mice [101]. Depletion of these cells using a transgenic CD11c-diphtheria toxin receptor model abolished the characteristic changes in eosinophilic inflammation, bronchial hyper-reactivity, and goblet cell hyperplasia [102]. The organization of lymphoid cells to form these tertiary lymphoid structures has also been seen in the lungs of mice without primary lymphoid organs [103], as well as in the lungs of humans with pulmonary complications of rheumatoid arthritis and Sjörgren syndrome [104]. Together, these studies suggest that the heterogeneity of mouse lung DC subsets, which arise and accumulate during lung inflammation, is diverse. Work still remains to define the function and fate of several of these DC subsets in the mouse, as well as in defining and characterizing their human counterparts.

HUMAN LUNG DCs

Characterization and function of human lung DC subsets have been complicated by a lack of validated markers and by difficulties in obtaining human lung tissues for investigation. A summary of current human DC subsets and their cell surface and activation markers is shown in Table 1. Human cDCs have the classic DC form and function and are subdivided into migratory cDCs and LNRDCs. Migratory cDCs emigrate from the peripheral tissues to regional draining LNs via the lymphatics. LNRDCs do not migrate but spend their lives within lymphoid tissues. Clinical samples that have been used to identify DC subsets in human lung include sputum and BALF from healthy control subjects. These cells are often compared with DCs in the sputum and BALF of individuals with clinical conditions, such as asthma, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, cancer, pneumonia, and sarcoidosis. Thus, comparisons should be made with caution, as the underlying clinical conditions are likely to influence DC trafficking, phenotype, and function. In such samples, human lung DCs are differentiated from resident AMs by their expression of MHC class II, usually HLA-DR. Additionally, human resident AMs are highly autofluorescent, whereas lung DCs are found among the low autofluorescent lung leukocytes [105]. Human lung DCs are also excluded from other lung leukocytes by the absence of T, B, and NK cell and monocyte and granulocyte lineage markers. BALF and sputum, however, may not have DCs from the parenchyma and thus, are likely poor sources of DCs for further study.

Until recently, one limitation to human lung DC research was the absence of a marker corresponding to the expression of CD8α by mouse lung DCs. It was therefore problematic to interpret functional studies of mouse CD8α+ DC subsets in terms of a corresponding functional subset among human lung DCs. A set of antibodies designated BDCA1–4, along with the integrin CD11c, has now been used to differentiate between pDC and different cDC subsets in humans [106]. MacDonald et al. [107] identified four subsets of human DCs using human blood, and several groups have started to identify subsets in the lung using the above markers [108–111]. Poulin et al. [112] recently identified three populations of human DCs in the spleen and human cord blood, including one that expresses high levels of BCDA3 (CD141) and Clec9a (DNGR-1), a C-type lectin expressed on subsets of human and mouse DCs. These human DCs resemble mouse CD8α+ in phenotype and function and express Necl2, CD207 (Langerin), Batf3, IFN regulatory factor 8, and TLR3. With the use of CXCR1 expression as a marker, Crozat et al. [113] demonstrated that expression of this marker is conserved across species, suggesting that CXCR1 expression may also help define human DC subsets that are homologous to murine CD8α+ DCs.

In humans, pDCs express CD123, the IL-3R, as well as the markers BDCA2, BDCA4, L-selectin, CD11c–/lo, and ILT7, which associates with the signal adaptor protein FcεRIγ to form a receptor complex [114]. In humans, pDCs appear to be functionally specialized for their ability to respond to viral antigens, as well as microbial components in the form of CpG DNA, and to activate and differentiate after exposure to IL-3 and CD40 ligand [115]. Upon activation, pDCs are specialized for their ability to produce IFN-α [116, 117]. pDCs have also been shown to play a role in dampening the immune response, for example, by priming IL-10-producing Tregs [118] or as demonstrated by preventing asthmatic reactions to harmless inhaled antigens [61]. pDCs are negatively regulated by engagement of the ILT7–FcεRIγ receptor complex, which inhibits the transcription and secretion of type I IFN and other cytokines [114].

Studies demonstrate that MHC class II+ cDCs are present in normal human airway mucosal epithelium, lung parenchyma, and visceral pleura [27] and have identified a Langrin+ DC subset in normal human lung bronchioles [119]. The BALF of healthy volunteers contains two main DC subsets—a cDC subset expressing CD11c and a pDC subset expressing CD123 [109]. Unlike in the BALF, where DCs are present in low numbers, cDCs in the lung parenchyma are present in large numbers. Like resident AMs, they are also associated with interalveolar septa [26, 29]. Demedts et al. [108] identified three DC subsets in normal human lung specimens: a CD1a+MHCII+BDCA1+ cDC subset and a pDC subset, which express BDCA2+ and CD123+ [106]. They identified a cDC subset that expresses BDCA3+ and CD11c+. Other studies confirmed the presence of these pDC and cDC subsets in the BALF of healthy, normal control subjects and in allergic asthmatics following allergen challenge, as well as in the BALF of subjects with sarcoidosis, interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, and pneumonia [120, 121]. A recent study used single-cell suspensions of human lung tissue to characterize and quantify Langerhans-type DCs in the small airways of current and ex-smokers, with and without COPD, and demonstrated a Langerin+ Langerhans-type DC subset and a DC-SIGN+ interstitial cDC subset [122]. The Langerin+ DCs were also CD1a+, BDCA1+, BCDA3+, BCDA4–, CD14–, and HLA-DRhi. The DC-SIGN+ interstitial cDCs did not differ between current smokers and subjects with COPD and are CD1a–, BDCA1–, BCDA3lo/+, BCDA4lo/+, CD14+, and HLA-DR+. Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated a selective accumulation of the Langerhans-type DC subset in small airways of current smokers and COPD subjects. Thus, in comparison with the state of knowledge of mouse lung DC subsets, many questions remain about the heterogeneity of human lung DC subsets under the steady state and in response to lung infection and disease.

MICROENVIRONMENT AND DC FUNCTION

Maintenance of lung homeostasis and generating an effective inflammatory and/or immune response in the lung are critical to maintain life. Lung DCs initiate all three of these responses, and yet, these functions are not only dictated by encounter with inhaled substances, they are also driven by the close functional relationship between lung DC subsets and other lung cells in the surrounding microenvironment. Airway ECs also express PRRs that recognize microbes and their products, as well as receptors for cytokines produced during inflammation. Ligation of these receptors signals ECs to up-regulate the expression of a wide variety of effector proteins, e.g., IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, chemokines, etc., all of which modulate the function of intraepithelial DCs. ECs respond to environmental stresses, such as diesel exhaust particles [123], by producing cytokines and chemokines that alter local DC function. TSLP, produced by respiratory ECs, alternatively activate DCs, which drive Th2-mediated allergic immune responses, although the role of TSLP in human chronic lung diseases, such as asthma and allergic rhinitis, has not been fully characterized [40, 124]. In humans and mice, allergen challenge is accompanied by blood monocyte recruitment into the inflamed airways and subsequent differentiation into inflammatory cDCs [125, 126]. The production of CCR17 and CCL22 by inflammatory cDCs has been shown to attract CCR4+ Th2 T cells into the airways and thereby, establish Th2-mediated lung pathology [127]. EC-derived TSLP has also been shown to induce cDC CCL17 production, further facilitating Th2-associated cell recruitment into the inflamed airways [128]. Human keratinocytes also produce TSLP after stimulation by ligands for TLR2, TLR3, TLR8, and TLR9 and by IL-4, IL-13, TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β [129]. TLSP produced by these nonmyeloid cells has been shown to be a powerful activator of immature DCs, driving their maturation into polarized cDCs, which are then able to fully activate naïve T cells for proliferation and differentiation. TSLP-activated, mature cDCs drive naïve T cell polarization toward the Th2 phenotype, and these polarized Th2 cells produce TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, but not IL-10 [130]. During the process of activating naïve T cells, TSLP-activated cDCs also induce the proliferation of Th2 central memory T cells, and in this manner, TSLP-activated DCs play a key role in the maintenance and polarization of the allergen-specific Th2 central memory T cell population in chronic allergic lung disease [131]. As a corollary to this finding, the lungs of human asthmatics have been shown to express increased levels of TSLP [132].

Resident AM and lung ECs play a critical role in these processes through their interactions with lung DCs. It may be that the major biological role of resident AM in the lung is to prevent inappropriate alveolar inflammation with resulting tissue damage and thereby, maintain normal alveolar gas exchange [133]. Resident AMs comprise >90% of the cells in the alveolar lumen, but a smaller population of DCs is also present [7, 39, 134]. Resident AMs adhere to integrin-expressing alveolar ECs [39] and indirectly contact DCs in the alveolar wall. Resident AMs live in close contact with DCs present in the alveolar lumen and may come into contact with cDCs that extend dendritic snorkels into the alveolar lumen, similar to those in the airway [60]. The close association contact among DCs, resident AMs, and alveolar ECs permits cross-regulation of cellular functions in these different cell types through communicating molecular signals such as chemokines and other cytokines. Communication between DCs and resident AMs is demonstrated by studies showing that depletion of resident AM up-regulates the APC function of lung DCs; thus, resident AMs actively suppress the lung DC ability to present antigens and induce inflammation, thereby maintaining lung homeostasis [7, 134, 135].

The respiratory tract is continuously exposed to innocuous airborne antigens and immunostimulatory molecules of microbial origin, such as LPS. At low concentrations, airborne LPS can induce a Th2-type response to harmless inhaled antigens in the lungs, thereby promoting allergic asthma. However, only a small fraction of people exposed to environmental LPS develops allergic asthma. What prevents most people from mounting a lung DC-driven Th2 response upon exposure to LPS is not understood. Bedoret et al. [136] have reported that lung interstitial macrophages prevent induction of a Th2-type response in mice challenged with LPS and an experimental harmless airborne antigen. Interstitial macrophages, but not AM, were found to produce high levels of IL-10 and to inhibit LPS-induced maturation and migration of DCs loaded with experimental, harmless airborne antigen in an IL-10-dependent manner. These investigators demonstrated further that elimination of interstitial macrophages in vivo led to overt asthmatic reactions to innocuous airborne antigens, inhaled with low doses of LPS. This study revealed a crucial role for interstitial macrophages in maintaining immune homeostasis in the respiratory tract and provides an explanation for the paradox—that although airborne LPS has the ability to promote the induction of Th2 responses by lung DCs, it does not provoke allergic asthma under normal conditions. Whether the same holds true for bacterial products other than LPS remains to be determined.

Lastly, DCs in the lung share many features and functions with professional APCs in other tissues, such as DCs in the GI tract and Langerhans cells in the skin. Nevertheless, because of differences in the host-environment interface in these tissues, distinct, functional responses are mediated by different subsets of DCs in each microenvironment. In the mouse, the majority of cDCs found in the lamina propria includes CD11b+, CD8α–, and MHC IIint/hi [137]. As noted earlier, human DCs do not express CD8α, and although the human counterpart to this cell has only been described recently (as reviewed by Ueno et al. [138]), its role in the GI tract is presently unknown. It should be noted that the microbiome of the GI tract can have a profound impact on the response of the lung to allergens and pathogens. Ichinohe et al. [139] reported recently that the composition of the commensal microbiota in the GI tract affects the generation of virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and antibody responses following respiratory influenza virus infection. A similar link may exist between the lung and the skin microbiome. Demehri et al. [140] reported that allergen challenge to the airways of mice engineered with a chronic skin-barrier defect and a spontaneous atopic dermatitis-like disorder resulted in a severe asthmatic phenotype not seen in similarly treated WT littermates. Furthermore, these investigators showed that TSLP, when overexpressed by skin keratinocytes, is the systemic driver of this airway hyper-responsiveness. Elimination of TSLP signaling in these animals blocked this asthmatic phenotype. Importantly, epidermal-derived TSLP was sufficient to sensitize the lung to inhaled allergens in the absence of epicutaneous sensitization by the same allergen. Although these investigators did not explore the potential connection between the skin microbiome and the ultimate sensitization of the lung by epidermal-derived TSLP, such a connection is likely to exist, especially when skin-barrier defects are also present. How TSLP specifically regulates DC function and skin-barrier function has been reviewed elsewhere [32, 141].

LUNG DCs AND DISEASE

Lung DCs play key roles in the pathogenesis of human lung diseases, such as asthma [142–144]. Human asthma is a chronic inflammatory lung disease characterized by the accumulation of T cells producing IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-13, and TNF-α, a cytokine profile characteristic of a Th2-mediated response to antigen. These Th2 cells produce IL-9 and IL-13, which mediate bronchial hyper-reactivity, recruit eosinophils and mast cells into sites of airway inflammation, and induce goblet cell hyperplasia. The daily balancing act among inhaled antigen, the airway-barrier ECs, and cells of the innate and acquired immune systems is mediated by mucosal and parenchymal lung DCs, which constitutively sample air at the air-epithelial-barrier interface [24, 145]. Allergens may evade endocytic airway DCs and gain direct access to other lung DC populations, for example, pDCs. Pollen aeroallergens contain enzymes that disrupt EC-tight junctions, allowing allergens to damage the air-epithelial-barrier interface and gain access to DC subsets found in the lung parenchyma [146].

Most inhaled antigens that gain entry into the lung parenchyma are transported from the lung via afferent lymphatics to regional LNs. As most inhaled antigens fail to fully activate the lung DC maturation program required for the expression of the three signals needed to fully activate naïve T cells, one outcome for most inhaled antigens is the induction of antigen-specific tolerance [61, 147, 148]. These types of antigens activate Tregs to produce IL-10 and TGF-β, which suppress the ability of DCs to fully activate T cells [147, 148]. Inhalation tolerance to antigen is also mediated by pDC antigen uptake, resulting in the suppression of cDCs through their ability to up-regulate antigen-specific Tregs [148]. Inhalation tolerance can then be broken by the exposure of airway cDCs to antigen in the presence of a PAMP. Uptake of antigen and concomitant PAMP recognition by a PRR drive immature cDC differentiation to mature cDCs, which are polarized in their ability to activate naïve T cells [149], and in human asthma, this requirement for dual activation signals for cDCs to drive T cell-mediated responses is shown by the association between TLR polymorphisms and asthma severity [150, 151].

REGULATORY MECHANISMS AND NETWORKS

Mechanisms other than the induction of tolerance can also reduce pathologic inflammation in the lung. A recent study [152] has shown that treatment of patients with intermittent-to-mild persistent asthma with omalizumab, a humanized IgG1 mAb that selectively binds to human IgE, decreased the numbers of airway cDCs from 126/mm2 (pretreatment) to 49/mm2 (2 months post-treatment). In contrast, this treatment did not alter the numbers of airway pDCs. The authors speculated that omalizumab diminished the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines from airway mast cells and thus, reduced chronic airway inflammation by migratory cDCs but not other inflammatory cells. Alternatively, a reduction in signaling via IgERs, expressed on cDCs as a consequence of omalizumab treatment, may have also led to the reduction in airway cDCs observed. Importantly, the decreased numbers of airway cDCs were associated with improved methacholine provocation responses and improved airway function.

IgE-mediated regulation of DC function is likely to play a key role in controlling inflammation in the lung triggered by allergens or respiratory viruses. Homeostatic (healthy, normal) circulating levels of serum IgE minimize spontaneous Th1-mediated airway inflammation, suggesting a physiological role for IgE in the regulation of Th cell differentiation. Homeostatic levels of IgE suppress IL-12 production in the spleen and lung, supporting the hypothesis that normal levels of IgE limit Th1 responses in vivo. Chung et al. [153] showed that experimental asthma after viral infection in mice depended on type I IFN-driven up-regulation of FcεRI expression on cDCs in the lung. FcεRI expression on lung cDCs also depends on a CD49d+ subset of PMN neutrophils. Thus, PMN neutrophil–cDC communication in the lung is necessary for the ability of viral infection to drive atopic disease. It was shown previously that IgE stimulates DCs directly through FcγRIII to suppress IL-12 production in vitro and influences APCs to skew CD4+ T cells toward Th2 differentiation. Blink and Fu [154] demonstrated recently a novel role for IgE in regulating differentiation of adaptive immune responses through direct interaction with FcγRIII on DCs. In a different study, pDCs from patients with asthma were shown to secrete significantly less type I IFN upon exposure to influenza A virus, and secretion was inversely correlated with serum IgE levels [155]. Moreover, IgE cross-linking prior to viral challenge resulted in abrogation of the influenza-induced pDC IFN response, diminished influenza, and gardiquimod-induced TLR7 up-regulation in pDCs and blocked influenza-induced up-regulation of pDC maturation/costimulatory molecules. In addition, exposure to influenza and gardiquimod resulted in up-regulation of TLR7, with concomitant down-regulation of FcεRI expression in pDCs. These data suggest that counter-regulation of FcεRI and TLR7 pathways exists in pDCs and that IgE cross-linking impairs pDC antiviral responses.

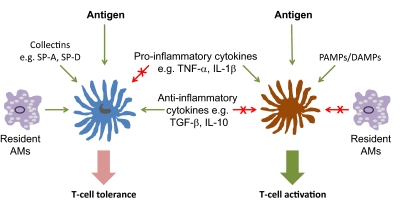

Taken together, and as illustrated in Fig. 3, these studies suggest that lung DCs have multiple layers of redundant systems, which upon activation, serve to regulate DC function. For example, the ability of DCs to recognize antigen in the absence and presence of a PAMP/DAMP represents one layer of regulation based on the initial interaction of lung DCs with inhaled antigens. Molecular systems such as PAMPs/ DAMPs, recognized by DC PRRs in association with antigen, are then linked to signaling pathways, which once activated, modulate DC function, thereby adding yet more complexity to DC function. The ability of other myeloid and nonmyeloid cells, for example, resident AMs, PMN neutrophils, mucosal ECs, or airway neurons [156], to regulate DC function may be considered a second layer in this system. As a first line of host defense, the ability of airway DCs to recognize and endocytose antigen, in particular, to engulf microbes by phagocytosis, is facilitated by the multiple receptor-based systems expressed on the surface of DCs [157]. These receptor systems can recognize host-derived proteins and then serve to opsonize the microbe for uptake by DCs. These host-derived proteins include activated complement fragments, the Fc portion of opsonizing antibodies that are bound to microbial proteins, such as flagellin and microbial carbohydrate-containing surface molecules (glycolipids and glycoprotein). In general, these DC surface receptor systems are also linked to downstream signal transduction molecules that culminate in the activation of several key enzymes including PKC, PI3K, PLC, and the Rho GTPases [157]. Activation of these enzyme systems mediates multiple cellular responses in DCs, such as enhanced membrane trafficking, cellular division, apoptosis, enhanced microbicidal activity, the production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, actin polymerization, cell motility and migration, cell differentiation, as well as antigen processing and presentation. Once activated through these systems, DC function may then be down-regulated by receptor systems, which engage anti-inflammatory cytokines and other signals that oppose the activation signals.

Figure 3. Complexity in the regulation of lung DC function.

Antigen-specific T cell tolerance (left) or activation (right) is regulated at multiple levels, some of which are mutually antagonistic. SP-A/D, Surfactant protein A/D.

As microbes or phagocytosed antigens are cleared from the host, cytokines that oppose the up-regulation of these antimicrobial pathways return the cells and therefore, the lungs to their normal steady state. For example, phagocytic uptake of most microbes results in the rapid production of ROS, which are involved in the intracellular killing of the pathogen. ROS can also increase downstream signaling pathways involving NF-κB, AP-1, MAPK, and PI3K. ROS are involved in the activation of DNA-based excision and repair pathways in most cells, thereby preventing the cell from dying after phagocytosis of a pathogen, which might damage host DNA. ROS, for example, NO [158] and hydrogen peroxide [159], serve multiple intracellular pathways required for full activation of DCs, as well as for cell survival and the up-regulation of cellular pathways promoting the differentiation of immature DCs into fully mature DCs. Fluctuations in the ebb and flow of these layers of regulation allow the lung and the host to recognize, respond to, and eliminate harmful substances and then return to the normal, steady state in which air exchange is maintained.

FUTURE CHALLENGES

In the last decade, there has been an explosion of information about the biology of DCs, resulting principally from the rapid development of new, immunologic techniques that permit a more comprehensive study of DCs and their complex interactions with other cells. Initial discoveries concerning DCs have been made primarily in rodent systems, but new technologies, including the availability of reagents and new markers, are allowing investigators to carefully explore the biology of human DCs. Translational research that transforms basic science discoveries into solutions for human health problems is one of the five priority areas identified by NIH for the targeting of future resources [160]. Recent work has advanced the fields of murine and human lung DC subsets, functions, ontogeny, and anatomical distributions and drawn attention to the growing importance of translational research in this area. The discovery of more markers to characterize human lung DC subsets and the intense efforts of several researchers in this area continue to propel this field. More research into tailoring specific activation and maturation of lung DCs, as well as specific release of cytokines, will most certainly advance the development of therapeutics and vaccines in the treatment of pulmonary infectious diseases, asthma, and cancer.

We are likely on the verge of harnessing the full potential of the human DC repertoire. Thorough analysis of DCs with tools such as comparative genomics, more markers, and better methods, as well as research at a fervent pace, will hopefully give us a way to manipulate human DCs effectively and safely. Understanding which DC subsets are the best therapeutic targets is essential, the goal of such manipulation to induce protective immunity to pathogens and cancer, more effective vaccinations, as well as inducing tolerance to asthma and in autoimmune diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (grant HL68628) and by the U.S. Department of Defense (grant DOD W81XWH-07-1-0550-Mason). The authors also wish to thank Dr. Elizabeth Redente for critical review of the manuscript and help in the preparation of the figures.

Footnotes

- AM

- alveolar macrophage

- BALF

- BAL fluid

- Batf3

- basic leucine zipper transcription factor activating transcription factor-like 3

- BDCA

- blood DC antigen

- CD11bhi DC

- CD11c+CD11bhiCD103–LangerinCD207–CD8α–DC

- CD103+ cDC

- CD11c+CD103+Langerin+ (CD207+) CD8α–CD11b–conventional DC

- cDC

- conventional DC

- COPD

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DAMP

- danger-associated molecular pattern

- DC-SIGN

- DC-specific ICAM-grabbing nonintegrin

- DNGR-1

- DC NK lectin group receptor 1

- EC

- epithelial cell

- GI

- gastrointestinal

- ILT7

- Ig-like transcript 7

- LNRDC

- LN resident DC

- MDP

- macrophage and DC precursor

- MPS

- mononuclear phagocyte system

- pDC

- plasmacytoid DC

- PDL1

- programmed death ligand 1

- RSV

- respiratory syncytial virus

- TiPDC

- TNF-α/iNOS-producing DC

- Treg

- T regulatory cell

- TSLP

- thymic stromal lymphopoietin

REFERENCES

- 1. Aschoff L. (1924) The reticuloendothelial system. Ergeb. Inn. Med. Kinderheilkd. 26, 1–118 [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Furth R., Cohn Z. A. (1968) The origin and kinetics of mononuclear phagocytes. J. Exp. Med. 128, 415–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gordon S., Taylor P. R. (2005) Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 953–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Volkman A., Gowans J. L. (1965) The origin of macrophages from bone marrow in the rat. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 46, 62–70 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steinman R. M., Cohn Z. A. (1973) Identification of a novel cell type in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. I. Morphology, quantitation, tissue distribution. J. Exp. Med. 137, 1142–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hume D. A. (2008) Macrophages as APC and the dendritic cell myth. J. Immunol. 181, 5829–5835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holt P. G., Strickland D. H., Wikstrom M. E., Jahnsen F. L. (2008) Regulation of immunological homeostasis in the respiratory tract. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 142–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Randall T. D. (2010) Pulmonary dendritic cells: thinking globally, acting locally. J. Exp. Med. 207, 451–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perrigoue J. G., Saenz S. A., Siracusa M. C., Allenspach E. J., Taylor B. C., Giacomin P. R., Nair M. G., Du Y., Zaph C., van Rooijen N., Comeau M. R., Pearce E. J., Laufer T. M., Artis D. (2009) MHC class II-dependent basophil-CD4+ T cell interactions promote T(H)2 cytokine-dependent immunity. Nat. Immunol. 10, 697–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sokol C. L., Chu N. Q., Yu S., Nish S. A., Laufer T. M., Medzhitov R. (2009) Basophils function as antigen-presenting cells for an allergen-induced T helper type 2 response. Nat. Immunol. 10, 713–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yoshimoto T., Yasuda K., Tanaka H., Nakahira M., Imai Y., Fujimori Y., Nakanishi K. (2009) Basophils contribute to T(H)2-IgE responses in vivo via IL-4 production and presentation of peptide-MHC class II complexes to CD4+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 10, 706–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang H. B., Ghiran I., Matthaei K., Weller P. F. (2007) Airway eosinophils: allergic inflammation recruited professional antigen-presenting cells. J. Immunol. 179, 7585–7592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Batista F. D., Harwood N. E. (2009) The who, how and where of antigen presentation to B cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 15–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen X., Jensen P. E. (2008) The role of B lymphocytes as antigen-presenting cells. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp.(Warsz.) 56, 77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reichardt P., Dornbach B., Rong S., Beissert S., Gueler F., Loser K., Gunzer M. (2007) Naive B cells generate regulatory T cells in the presence of a mature immunologic synapse. Blood 110, 1519–1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hughes C. C., Savage C. O., Pober J. S. (1990) Endothelial cells augment T cell interleukin 2 production by a contact-dependent mechanism involving CD2/LFA-3 interaction. J. Exp. Med. 171, 1453–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kreisel D., Krupnick A. S., Balsara K. R., Riha M., Gelman A. E., Popma S. H., Szeto W. Y., Turka L. A., Rosengard B. R. (2002) Mouse vascular endothelium activates CD8+ T lymphocytes in a B7-dependent fashion. J. Immunol. 169, 6154–6161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mestas J., Hughes C. C. (2001) Endothelial cell costimulation of T cell activation through CD58-CD2 interactions involves lipid raft aggregation. J. Immunol. 167, 4378–4385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murphy L. L., Mazanet M. M., Taylor A. C., Mestas J., Hughes C. C. (1999) Single-cell analysis of costimulation by B cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts demonstrates heterogeneity in responses of CD4(+) memory T cells. Cell. Immunol. 194, 150–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fokkens W. J., Vroom T. M., Rijntjes E., Mulder P. G. (1989) CD-1 (T6), HLA-DR-expressing cells, presumably Langerhans cells, in nasal mucosa. Allergy 44, 167–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gong J. L., McCarthy K. M., Telford J., Tamatani T., Miyasaka M., Schneeberger E. E. (1992) Intraepithelial airway dendritic cells: a distinct subset of pulmonary dendritic cells obtained by microdissection. J. Exp. Med. 175, 797–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holt P. G., Schon-Hegrad M. A., Phillips M. J., McMenamin P. G. (1989) Ia-positive dendritic cells form a tightly meshed network within the human airway epithelium. Clin. Exp. Allergy 19, 597–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. von Garnier C., Filgueira L., Wikstrom M., Smith M., Thomas J. A., Strickland D. H., Holt P. G., Stumbles P. A. (2005) Anatomical location determines the distribution and function of dendritic cells and other APCs in the respiratory tract. J. Immunol. 175, 1609–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jahnsen F. L., Strickland D. H., Thomas J. A., Tobagus I. T., Napoli S., Zosky G. R., Turner D. J., Sly P. D., Stumbles P. A., Holt P. G. (2006) Accelerated antigen sampling and transport by airway mucosal dendritic cells following inhalation of a bacterial stimulus. J. Immunol. 177, 5861–5867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blank F., Rothen-Rutishauser B., Gehr P. (2007) Dendritic cells and macrophages form a transepithelial network against foreign particulate antigens. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 36, 669–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holt P. G., Schon-Hegrad M. A. (1987) Localization of T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells in rat respiratory tract tissue: implications for immune function studies. Immunology 62, 349–356 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sertl K., Takemura T., Tschachler E., Ferrans V. J., Kaliner M. A., Shevach E. M. (1986) Dendritic cells with antigen-presenting capability reside in airway epithelium, lung parenchyma, and visceral pleura. J. Exp. Med. 163, 436–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nelson D. J., McMenamin C., McWilliam A. S., Brenan M., Holt P. G. (1994) Development of the airway intraepithelial dendritic cell network in the rat from class II major histocompatibility (Ia)-negative precursors: differential regulation of Ia expression at different levels of the respiratory tract. J. Exp. Med. 179, 203–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schon-Hegrad M. A., Oliver J., McMenamin P. G., Holt P. G. (1991) Studies on the density, distribution, and surface phenotype of intraepithelial class II major histocompatibility complex antigen (Ia)-bearing dendritic cells (DC) in the conducting airways. J. Exp. Med. 173, 1345–1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McWilliam A. S., Napoli S., Marsh A. M., Pemper F. L., Nelson D. J., Pimm C. L., Stumbles P. A., Wells T. N., Holt P. G. (1996) Dendritic cells are recruited into the airway epithelium during the inflammatory response to a broad spectrum of stimuli. J. Exp. Med. 184, 2429–2432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Holt P. G., Haining S., Nelson D. J., Sedgwick J. D. (1994) Origin and steady-state turnover of class II MHC-bearing dendritic cells in the epithelium of the conducting airways. J. Immunol. 153, 256–261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu K., Victora G. D., Schwickert T. A., Guermonprez P., Meredith M. M., Yao K., Chu F. F., Randolph G. J., Rudensky A. Y., Nussenzweig M. (2009) In vivo analysis of dendritic cell development and homeostasis. Science 324, 392–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Auffray C., Fogg D., Garfa M., Elain G., Join-Lambert O., Kayal S., Sarnacki S., Cumano A., Lauvau G., Geissmann F. (2007) Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science 317, 666–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kapsenberg M. L. (2003) Dendritic-cell control of pathogen-driven T-cell polarization. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 984–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iwasaki A. (2007) Mucosal dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 381–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shortman K., Liu Y. J. (2002) Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 151–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shortman K., Naik S. H. (2007) Steady-state and inflammatory dendritic-cell development. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 19–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu L., Liu Y. J. (2007) Development of dendritic-cell lineages. Immunity 26, 741–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tournier J. N., Mohamadzadeh M. (2008) Microenvironmental impact on lung cell homeostasis and immunity during infection. Expert Rev. Vaccines 7, 457–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Van Tongeren J., Reinartz S. M., Fokkens W. J., de Jong E. C., van Drunen C. M. (2008) Interactions between epithelial cells and dendritic cells in airway immune responses: lessons from allergic airway disease. Allergy 63, 1124–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Steinman R. M., Hawiger D., Nussenzweig M. C. (2003) Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 685–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Crouch E., Wright J. R. (2001) Surfactant proteins a and d and pulmonary host defense. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 63, 521–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Freudenberg M. A., Tchaptchet S., Keck S., Fejer G., Huber M., Schutze N., Beutler B., Galanos C. (2008) Lipopolysaccharide sensing an important factor in the innate immune response to Gram-negative bacterial infections: benefits and hazards of LPS hypersensitivity. Immunobiology 213, 193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Haagsman H. P., Hogenkamp A., van Eijk M., Veldhuizen E. J. (2008) Surfactant collectins and innate immunity. Neonatology 93, 288–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jin M. S., Lee J. O. (2008) Structures of the Toll-like receptor family and its ligand complexes. Immunity 29, 182–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jin M. S., Lee J. O. (2008) Structures of TLR-ligand complexes. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 20, 414–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kawai T., Akira S. (2007) TLR signaling. Semin. Immunol. 19, 24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kawai T., Akira S. (2010) The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 11, 373–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Manfredi A. A., Rovere-Querini P., Bottazzi B., Garlanda C., Mantovani A. (2008) Pentraxins, humoral innate immunity and tissue injury. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 20, 538–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roozendaal R., Carroll M. C. (2006) Emerging patterns in complement-mediated pathogen recognition. Cell 125, 29–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Takeda K., Akira S. (2007) Toll-like receptors. In Current Protocols in Immunology (Coico R., ed.), Chapter 14, John Wiley and Sons, Malden, MA, USA, 14.12.1–14.12.13 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Takeda K., Kaisho T., Akira S. (2003) Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 335–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Takeuchi O., Sato S., Horiuchi T., Hoshino K., Takeda K., Dong Z., Modlin R. L., Akira S. (2002) Cutting edge: role of Toll-like receptor 1 in mediating immune response to microbial lipoproteins. J. Immunol. 169, 10–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Van Vliet S. J., Garcia-Vallejo J. J., van Kooyk Y. (2008) Dendritic cells and C-type lectin receptors: coupling innate to adaptive immune responses. Immunol. Cell Biol. 86, 580–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang X. L., Ali M. A. (2008) Ficolins: structure, function and associated diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 632, 105–115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sugawara I., Yamada H., Li C., Mizuno S., Takeuchi O., Akira S. (2003) Mycobacterial infection in TLR2 and TLR6 knockout mice. Microbiol. Immunol. 47, 327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ahonen C. L., Doxsee C. L., McGurran S. M., Riter T. R., Wade W. F., Barth R. J., Vasilakos J. P., Noelle R. J., Kedl R. M. (2004) Combined TLR and CD40 triggering induces potent CD8+ T cell expansion with variable dependence on type I IFN. J. Exp. Med. 199, 775–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. McWilliams J. A., Sanchez P. J., Haluszczak C., Gapin L., Kedl R. M. (2010) Multiple innate signaling pathways cooperate with CD40 to induce potent, CD70-dependent cellular immunity. Vaccine 28, 1468–1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sanchez P. J., McWilliams J. A., Haluszczak C., Yagita H., Kedl R. M. (2007) Combined TLR/CD40 stimulation mediates potent cellular immunity by regulating dendritic cell expression of CD70 in vivo. J. Immunol. 178, 1564–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. De Heer H. J., Hammad H., Kool M., Lambrecht B. N. (2005) Dendritic cell subsets and immune regulation in the lung. Semin. Immunol. 17, 295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. De Heer H. J., Hammad H., Soullie T., Hijdra D., Vos N., Willart M. A., Hoogsteden H. C., Lambrecht B. N. (2004) Essential role of lung plasmacytoid dendritic cells in preventing asthmatic reactions to harmless inhaled antigen. J. Exp. Med. 200, 89–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Oriss T. B., Ostroukhova M., Seguin-Devaux C., Dixon-McCarthy B., Stolz D. B., Watkins S. C., Pillemer B., Ray P., Ray A. (2005) Dynamics of dendritic cell phenotype and interactions with CD4+ T cells in airway inflammation and tolerance. J. Immunol. 174, 854–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Randolph G. J., Jakubzick C., Qu C. (2008) Antigen presentation by monocytes and monocyte-derived cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 20, 52–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Serbina N. V., Salazar-Mather T. P., Biron C. A., Kuziel W. A., Pamer E. G. (2003) TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells mediate innate immune defense against bacterial infection. Immunity 19, 59–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liu Y. J. (2005) IPC: professional type 1 interferon-producing cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23, 275–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Aldridge J. R., Jr., Moseley C. E., Boltz D. A., Negovetich N. J., Reynolds C., Franks J., Brown S. A., Doherty P. C., Webster R. G., Thomas P. G. (2009) TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells are the necessary evil of lethal influenza virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 5306–5311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. De Trez C., Magez S., Akira S., Ryffel B., Carlier Y., Muraille E. (2009) iNOS-producing inflammatory dendritic cells constitute the major infected cell type during the chronic Leishmania major infection phase of C57BL/6 resistant mice. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ito T., Carson W. F. t., Cavassani K. A., Connett J. M., Kunkel S. L. (2011) CCR6 as a mediator of immunity in the lung and gut. Exp. Cell Res. 317, 613–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kallal L. E., Schaller M. A., Lindell D. M., Lira S. A., Lukacs N. W. (2010) CCL20/CCR6 blockade enhances immunity to RSV by impairing recruitment of DC. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 1042–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Robays L. J., Maes T., Lebecque S., Lira S. A., Kuziel W. A., Brusselle G. G., Joos G. F., Vermaelen K. V. (2007) Chemokine receptor CCR2 but not CCR5 or CCR6 mediates the increase in pulmonary dendritic cells during allergic airway inflammation. J. Immunol. 178, 5305–5311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Otero K., Vecchi A., Hirsch E., Kearley J., Vermi W., Del Prete A., Gonzalvo-Feo S., Garlanda C., Azzolino O., Salogni L., Lloyd C. M., Facchetti F., Mantovani A., Sozzani S. (2010) Nonredundant role of CCRL2 in lung dendritic cell trafficking. Blood 116, 2942–2949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tacke F., Ginhoux F., Jakubzick C., van Rooijen N., Merad M., Randolph G. J. (2006) Immature monocytes acquire antigens from other cells in the bone marrow and present them to T cells after maturing in the periphery. J. Exp. Med. 203, 583–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Varol C., Landsman L., Fogg D. K., Greenshtein L., Gildor B., Margalit R., Kalchenko V., Geissmann F., Jung S. (2007) Monocytes give rise to mucosal, but not splenic, conventional dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 204, 171–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Jakubzick C., Tacke F., Ginhoux F., Wagers A. J., van Rooijen N., Mack M., Merad M., Randolph G. J. (2008) Blood monocyte subsets differentially give rise to CD103+ and CD103– pulmonary dendritic cell populations. J. Immunol. 180, 3019–3027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cisse B., Caton M. L., Lehner M., Maeda T., Scheu S., Locksley R., Holmberg D., Zweier C., den Hollander N. S., Kant S. G., Holter W., Rauch A., Zhuang Y., Reizis B. (2008) Transcription factor E2–2 is an essential and specific regulator of plasmacytoid dendritic cell development. Cell 135, 37–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ghosh H. S., Cisse B., Bunin A., Lewis K. L., Reizis B. (2010) Continuous expression of the transcription factor e2–2 maintains the cell fate of mature plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunity 33, 905–916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Nagasawa M., Schmidlin H., Hazekamp M. G., Schotte R., Blom B. (2008) Development of human plasmacytoid dendritic cells depends on the combined action of the basic helix-loop-helix factor E2–2 and the Ets factor Spi-B. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 2389–2400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Crozat K., Guiton R., Guilliams M., Henri S., Baranek T., Schwartz-Cornil I., Malissen B., Dalod M. (2010) Comparative genomics as a tool to reveal functional equivalences between human and mouse dendritic cell subsets. Immunol. Rev. 234, 177–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Henri S., Vremec D., Kamath A., Waithman J., Williams S., Benoist C., Burnham K., Saeland S., Handman E., Shortman K. (2001) The dendritic cell populations of mouse lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 167, 741–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Vremec D., Shortman K. (1997) Dendritic cell subtypes in mouse lymphoid organs: cross-correlation of surface markers, changes with incubation, and differences among thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 159, 565–573 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Sung S. S., Fu S. M., Rose C. E., Jr., Gaskin F., Ju S. T., Beaty S. R. (2006) A major lung CD103 (αE)-β7 integrin-positive epithelial dendritic cell population expressing Langerin and tight junction proteins. J. Immunol. 176, 2161–2172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Jakob T., Udey M. C. (1998) Regulation of E-cadherin-mediated adhesion in Langerhans cell-like dendritic cells by inflammatory mediators that mobilize Langerhans cells in vivo. J. Immunol. 160, 4067–4073 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Masten B. J., Lipscomb M. F. (1999) Comparison of lung dendritic cells and B cells in stimulating naive antigen-specific T cells. J. Immunol. 162, 1310–1317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Masten B. J., Olson G. K., Kusewitt D. F., Lipscomb M. F. (2004) Flt3 ligand preferentially increases the number of functionally active myeloid dendritic cells in the lungs of mice. J. Immunol. 172, 4077–4083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Asselin-Paturel C., Boonstra A., Dalod M., Durand I., Yessaad N., Dezutter-Dambuyant C., Vicari A., O′Garra A., Biron C., Briere F., Trinchieri G. (2001) Mouse type I IFN-producing cells are immature APCs with plasmacytoid morphology. Nat. Immunol. 2, 1144–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Nakano H., Yanagita M., Gunn M. D. (2001) CD11c(+)B220(+)Gr-1(+) cells in mouse lymph nodes and spleen display characteristics of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 194, 1171–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Faure-André G., Vargas P., Yuseff M. I., Heuze M., Diaz J., Lankar D., Steri V., Manry J., Hugues S., Vascotto F., Boulanger J., Raposo G., Bono M. R., Rosemblatt M., Piel M., Lennon-Dumenil A. M. (2008) Regulation of dendritic cell migration by CD74, the MHC class II-associated invariant chain. Science 322, 1705–1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Matta B. M., Castellaneta A., Thomson A. W. (2010) Tolerogenic plasmacytoid DC. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 2667–2676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Bonnefoy F., Couturier M., Clauzon A., Remy-Martin J. P., Gaugler B., Tiberghien P., Chen W., Saas P., Perruche S. (2011) TGF-{β}-exposed plasmacytoid dendritic cells participate in Th17 commitment. J. Immunol. 186, 6157–6164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Allan R. S., Waithman J., Bedoui S., Jones C. M., Villadangos J. A., Zhan Y., Lew A. M., Shortman K., Heath W. R., Carbone F. R. (2006) Migratory dendritic cells transfer antigen to a lymph node-resident dendritic cell population for efficient CTL priming. Immunity 25, 153–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Belz G. T., Bedoui S., Kupresanin F., Carbone F. R., Heath W. R. (2007) Minimal activation of memory CD8+ T cell by tissue-derived dendritic cells favors the stimulation of naive CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 8, 1060–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Carbone F. R., Belz G. T., Heath W. R. (2004) Transfer of antigen between migrating and lymph node-resident DCs in peripheral T-cell tolerance and immunity. Trends Immunol. 25, 655–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Belz G. T., Smith C. M., Kleinert L., Reading P., Brooks A., Shortman K., Carbone F. R., Heath W. R. (2004) Distinct migrating and nonmigrating dendritic cell populations are involved in MHC class I-restricted antigen presentation after lung infection with virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 8670–8675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Edelson B. T., Kc W., Juang R., Kohyama M., Benoit L. A., Klekotka P. A., Moon C., Albring J. C., Ise W., Michael D. G., Bhattacharya D., Stappenbeck T. S., Holtzman M. J., Sung S. S., Murphy T. L., Hildner K., Murphy K. M. (2010) Peripheral CD103+ dendritic cells form a unified subset developmentally related to CD8α+ conventional dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 207, 823–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Hildner K., Edelson B. T., Purtha W. E., Diamond M., Matsushita H., Kohyama M., Calderon B., Schraml B. U., Unanue E. R., Diamond M. S., Schreiber R. D., Murphy T. L., Murphy K. M. (2008) Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8α+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science 322, 1097–1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Osterholzer J. J., Ames T., Polak T., Sonstein J., Moore B. B., Chensue S. W., Toews G. B., Curtis J. L. (2005) CCR2 and CCR6, but not endothelial selectins, mediate the accumulation of immature dendritic cells within the lungs of mice in response to particulate antigen. J. Immunol. 175, 874–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. McGill J., Van Rooijen N., Legge K. L. (2008) Protective influenza-specific CD8 T cell responses require interactions with dendritic cells in the lungs. J. Exp. Med. 205, 1635–1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. GeurtsvanKessel C. H., Willart M. A., Bergen I. M., van Rijt L. S., Muskens F., Elewaut D., Osterhaus A. D., Hendriks R., Rimmelzwaan G. F., Lambrecht B. N. (2009) Dendritic cells are crucial for maintenance of tertiary lymphoid structures in the lung of influenza virus-infected mice. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2339–2349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Hohl T. M., Rivera A., Lipuma L., Gallegos A., Shi C., Mack M., Pamer E. G. (2009) Inflammatory monocytes facilitate adaptive CD4 T cell responses during respiratory fungal infection. Cell Host Microbe 6, 470–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Lukens M. V., Kruijsen D., Coenjaerts F. E., Kimpen J. L., van Bleek G. M. (2009) Respiratory syncytial virus-induced activation and migration of respiratory dendritic cells and subsequent antigen presentation in the lung-draining lymph node. J. Virol. 83, 7235–7243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Van Rijt L. S., Prins J. B., Leenen P. J., Thielemans K., de Vries V. C., Hoogsteden H. C., Lambrecht B. N. (2002) Allergen-induced accumulation of airway dendritic cells is supported by an increase in CD31(hi)Ly-6C(neg) bone marrow precursors in a mouse model of asthma. Blood 100, 3663–3671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Van Rijt L. S., Jung S., Kleinjan A., Vos N., Willart M., Duez C., Hoogsteden H. C., Lambrecht B. N. (2005) In vivo depletion of lung CD11c+ dendritic cells during allergen challenge abrogates the characteristic features of asthma. J. Exp. Med. 201, 981–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Moyron-Quiroz J. E., Rangel-Moreno J., Kusser K., Hartson L., Sprague F., Goodrich S., Woodland D. L., Lund F. E., Randall T. D. (2004) Role of inducible bronchus associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in respiratory immunity. Nat. Med. 10, 927–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Rangel-Moreno J., Hartson L., Navarro C., Gaxiola M., Selman M., Randall T. D. (2006) Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in patients with pulmonary complications of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 3183–3194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. van Haarst J. M., Verhoeven G. T., de Wit H. J., Hoogsteden H. C., Debets R., Drexhage H. A. (1996) CD1a+ and CD1a– accessory cells from human bronchoalveolar lavage differ in allostimulatory potential and cytokine production. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 15, 752–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Dzionek A., Fuchs A., Schmidt P., Cremer S., Zysk M., Miltenyi S., Buck D. W., Schmitz J. (2000) BDCA-2, BDCA-3, and BDCA-4: three markers for distinct subsets of dendritic cells in human peripheral blood. J. Immunol. 165, 6037–6046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. MacDonald K. P., Munster D. J., Clark G. J., Dzionek A., Schmitz J., Hart D. N. (2002) Characterization of human blood dendritic cell subsets. Blood 100, 4512–4520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Demedts I. K., Brusselle G. G., Vermaelen K. Y., Pauwels R. A. (2005) Identification and characterization of human pulmonary dendritic cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 32, 177–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Donnenberg V. S., Donnenberg A. D. (2003) Identification, rare-event detection and analysis of dendritic cell subsets in broncho-alveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood by flow cytometry. Front. Biosci. 8, s1175–s1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Masten B. J., Olson G. K., Tarleton C. A., Rund C., Schuyler M., Mehran R., Archibeque T., Lipscomb M. F. (2006) Characterization of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in human lung. J. Immunol. 177, 7784–7793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Ueno H., Klechevsky E., Morita R., Aspord C., Cao T., Matsui T., Di Pucchio T., Connolly J., Fay J. W., Pascual V., Banchereau J. (2007) Dendritic cell subsets in health and disease. Immunol. Rev. 219, 118–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]