Abstract

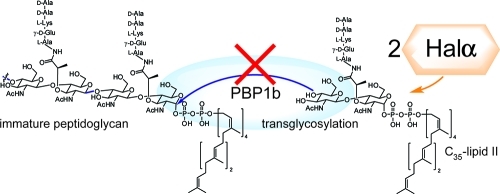

The two-peptide lantibiotic haloduracin is composed of two post-translationally modified polycyclic peptides that synergistically act on Gram-positive bacteria. We show here that Halα inhibits the transglycosylation reaction catalyzed by PBP1b by binding in a 2:1 stoichiometry to its substrate lipid II. Halβ and the mutant Halα-E22Q were not able to inhibit this step in peptidoglycan biosynthesis, but Halα with its leader peptide still attached was a potent inhibitor. Combined with previous findings, the data support a model in which a 1:2:2 lipid II:Halα:Halβ complex inhibits cell wall biosynthesis and mediates pore formation, resulting in loss of membrane potential and potassium efflux.

Inhibition of peptidoglycan biosynthesis is a common mode of action of many natural product antibiotics. Among the various ways of disrupting cell wall biosynthesis, sequestration of lipid II (Figure 1A) is particularly powerful. Lipid II is the substrate for the polymerases that generate the oligosaccharide chains of peptidoglycan. Bacterial resistance to compounds that bind to lipid II, such as nisin,(1) vancomycin,(2) and ramoplanin,3−6 has been slow to develop, possibly because in comparison with other resistance mechanisms such as efflux pumps and enzyme mutations, it is more challenging to change the structure of an advanced intermediate that is biosynthesized in 10 steps.7,8

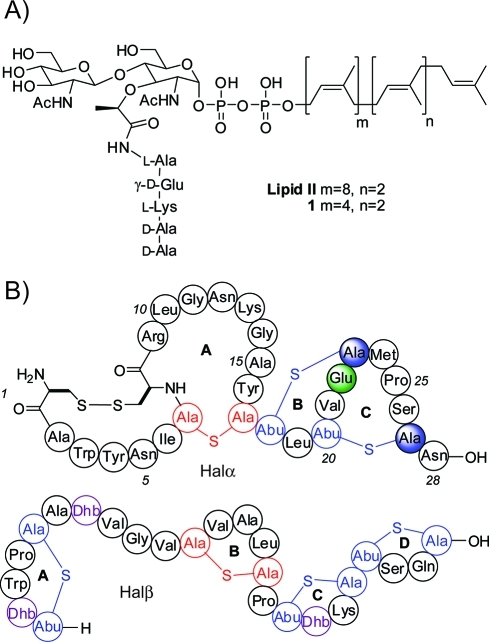

Figure 1.

(A) Structures of lipid II and an analogue 1 used in this study with a shortened prenyl chain. (B) Structures of Halα and Halβ. Shaded circles indicate residues mutated in this study. Abu, 2-aminobutyric acid; Dhb, dehydrobutyrine.

Several structurally diverse members of the lantibiotics have been reported to bind to lipid II.1,9−13 Lantibiotics are ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides characterized by thioether cross-links.(14) Two-peptide lantibiotics consist of two compounds that function synergistically to kill a range of Gram-positive bacteria.(15) In a recently proposed model for their synergistic activity, the α-peptide binds to lipid II in stoichiometric fashion, generating a binding site for the β-peptide.12,16 A 1:1:1 trimeric complex is then believed to form pores in the cell membrane, which results in the efflux of potassium and disruption of the membrane potential.(12) In this work, we evaluated this model with the two-peptide lantibiotic haloduracin and carried out structure–activity studies with haloduracin analogues. We show that the stoichiometry of binding lipid II by the α-peptide of haloduracin is 1:2 (lipid II:Halα).

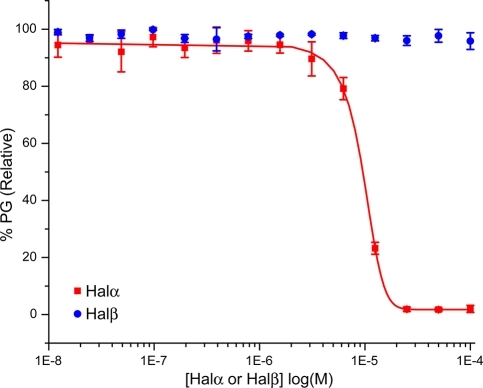

The two peptides that make up haloduracin are shown in Figure 1B.17,18 Halα contains several overlapping rings, including the B ring (residues 18–23) that is present in a variety of lantibiotics (including mersacidin(10) and lacticin 3147(19)) and has been proposed to be important for lipid II binding.20,21 Halβ has a more elongated structure and does not contain any overlapping rings (Figure 1B). To evaluate binding to lipid II, we used a previously reported in vitro assay that monitors the catalytic activity of PBP1b from Escherichia coli.(22) PBP1b uses lipid II as a substrate for glycan polymerization. Halα inhibited PBP1b-catalyzed peptidoglycan formation using 4 μM heptaprenyl lipid II 1 (Figure 1A) with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 9.6 ± 0.4 μM (Figure 2). In contrast, Halβ did not inhibit lipid II polymerization at concentrations up to 100 μM. We also tested a series of other post-translationally modified peptides as potential inhibitors of the polymerization process. The lantibiotics epilancin 15X,(23) lactocin S,24,25 and cinnamycin26,27 did not demonstrate any inhibitory activity at concentrations up to 200 μM. Similarly, the S-linked glycopeptide sublancin(28) did not inhibit lipid II polymerization at these levels. We therefore concentrated our further efforts on haloduracin.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of PBP1b-catalyzed formation of peptidoglycan (PG) by Halα and Halβ. The lipid II concentration was 4 μM.

A Halα mutant in which Cys23 was mutated to Ala,29,30 thereby disrupting the B-ring structure, still inhibited lipid II polymerization, albeit with a 5-fold increase in the IC50 value (50.7 ± 1.7 μM) relative to wild-type (wt) Halα (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). Mutation of the highly conserved Glu22 within the B ring to Gln abolished inhibition at concentrations up to 100 μM. However, a C-ring Cys27 → Ala mutant did inhibit polymerization, but in a less potent manner than wt Halα (IC50 = 29.5 ± 3.5 μM; Figure S1). The B- and C-ring mutants were previously evaluated for their antimicrobial activity against Lactococcus lactis HP.29,30 The combination of wt Halα and Halβ resulted in a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 0.039 μM, whereas the use of wt Halβ with Halα-C23A or Halα-C27A yielded MIC values of 0.39 and 1.56 μM, respectively. It is not possible to compare directly the effects of these mutations on the antimicrobial activity and in vitro inhibition of lipid II polymerization because of different components that are present in each assay, including the membrane of whole cells in the antimicrobial assay. Nevertheless, the relative effects can be compared for each assay type. The larger deleterious effect on antimicrobial activity of the C27A mutation compared to the C23A mutation despite its higher affinity for lipid II suggests that disruption of the C ring has an additional deleterious effect on the interaction with Halβ compared with disruption of the B ring. Conversely, the Halα-E22Q MIC of 1.56 μM when combined with wt-Halβ(30) was not expected given that the peptide did not inhibit in vitro polymerization. In the context of the membrane of whole cells and the presence of Halβ, the compound may regain some of its binding activity. Binding is still very weak, however, because the MIC of the combination treatment is only 4-fold lower than that of Halβ by itself (6.25 μM).

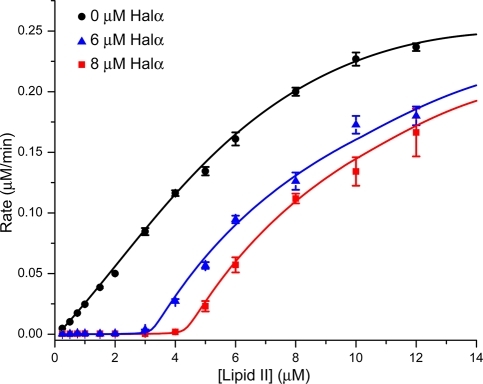

The kinetics of the inhibition of the polymerization reaction catalyzed by PBP1b were examined next with wt Halα. As shown in Figure 3, the dependence of the reaction rate on the lipid II concentration exhibits Michaelis–Menten-like kinetics. In the presence of 6 μM Halα, the reaction was fully inhibited until the lipid II concentration exceeded 3 μM. Similarly, at a Halα concentration of 8 μM, the reaction was completely inhibited until the lipid II concentration exceeded 4 μM. This type of behavior is similar to the inhibition of this process by ramoplanin(31) and indicates that Halα forms a tight complex with lipid II with a 2:1 stoichiometry (Halα:lipid II).(32) This stoichiometry is reminiscent of the 2:1 ratio of nisin to lipid II in pores formed in bacterial membranes.(33) The data do not allow a precise determination of a KD for Halα binding to lipid II,(34) but the inhibition curves in Figure 3 imply a nanomolar binding constant. Because previous work has demonstrated that like other two-peptide lantibiotics,(16) Halα and Halβ act in 1:1 stoichiometry,(30) the data further suggest that haloduracin inhibits peptidoglycan formation and causes pore formation by forming a lipid II:Halα:Halβ complex with 1:2:2 stoichiometry.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of lipid II polymerization by PBP1b and inhibition of this process by Halα.

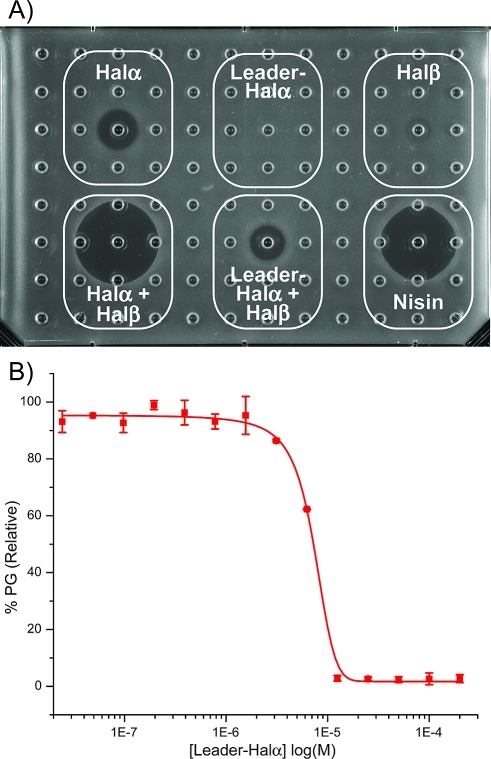

The Halα mutants used in this work were made using a previously described in vitro reconstituted biosynthesis.17,29 In this process, the lanthionine synthetase HalM1 carries out a series of post-translational modifications on the HalA1 precursor peptide that result in the thioether cross-links shown in Figure 1B. The precursor peptide has an additional N-terminal extension of 41 amino acids called the leader peptide that is important for recognition by HalM1. In addition, the leader peptides of lantibiotic precursor peptides are generally believed to keep their products inactive while they are synthesized in the cytoplasm.35−39 For haloduracin, the bifunctional protease/transporter HalT is believed to remove the leader peptide. HalT has not been investigated to date, but in a related system for the lantibiotic lacticin 481, the dedicated protease domain of the transporter LctT removes the leader peptide of modified LctA precursor peptide and secretes the final product.37,40 Given the common belief that lantibiotics with their leader peptides still attached are inactive, we were surprised to find that Halα containing its leader peptide (leader-Halα) appeared to have antimicrobial activity against L. lactis HP when combined with Halβ (Figure 4A). The activity is low relative to Halα without its leader peptide attached, and antimicrobial activity of leader-Halα was seen only in the presence of Halβ. We speculated that the indicator strain may secrete a protease that removes all or part of the leader peptide from a small subset of Halα molecules, resulting in the observed activity. Alternatively, Halα with its leader peptide attached may still engage with lipid II. To test the latter explanation, the polymerization assay was conducted in the presence of leader-Halα. Indeed, this peptide proved to be a potent inhibitor of lipid II polymerization with an IC50 of 7.1 ± 0.2 μM (with 4 μM lipid II; Figure 4B), similar to the activity of wt-Halα. The weaker antimicrobial activity of leader-Halα with wt Halβ relative to Halα combined with Halβ (Figure 4A) is likely a consequence of the less optimal synergy between the two peptides when the leader peptide is still attached to Halα. Furthermore, the leader peptide of Halα is highly negatively charged (four Glu, three Asp, one Arg, one Lys)17,18 with a stretch of four negatively charged residues near the junction between the leader peptide and the core peptide. These negative charges are likely to significantly weaken the binding of leader-Halα to lipid II in the context of a negatively charged membrane, explaining why the antimicrobial activity in Figure 4A is weaker than anticipated on the basis of the strong inhibition of the polymerization process by leader-Halα.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity and enzyme inhibitory activity of Halα with its leader peptide attached. (A) Agar diffusion growth inhibition assay against L. lactis HP. Inhibitory activity was assessed using the individual peptides alone (50 μM Halα, 50 μM Leader-Halα, and 50 μM Halβ, upper row) and in combination (at 50 μM) with 50 μM Halβ (lower row, left and center). Nisin was used as a control at a 50 μM concentration (lower right). (B) Inhibition of the PBP1b-catalyzed formation of peptidoglycan (PG) by leader-Halα.

In summary, this study has shown that Halα inhibits PBP1b by binding to its substrate lipid II in 2:1 stoichiometry. Glu22 is essential for this interaction, and the B and C rings are important but not critical. Attachment of the leader peptide does not prevent Halα from binding to lipid II, but because the leader is removed during secretion, lipid II does not encounter leader-Halα in the context of the producer strain. In combination with previous studies, the results presented here suggest that haloduracin’s antimicrobial activity is achieved in 1:2:2 lipid II:Halα:Halβ stoichiometry.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (GM58822 to W.A.v.d.D; GM067610 to S.W. and D.K.) and a U.S. National Institutes of Health Cellular and Molecular Biology Training Grant (T32 GM007283 to T.J.O.). We thank Ms. Xiao Yang for preparation of leader-Halα and Avena Ross and Prof. J. C. Vederas (University of Alberta) for providing lactocin S.

Supporting Information Available

Procedures for preparation of Halα and Halβ and their derivatives, preparation of the lipid II substrate 1 and PBP1b, and procedures for the transglycosylase and antimicrobial assays. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Breukink E.; Wiedemann I.; van Kraaij C.; Kuipers O. P.; Sahl H.; de Kruijff B. Science 1999, 286, 2361–2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuhashi M.; Dietrich C. P.; Strominger J. L. J. Biol. Chem. 1967, 242, 3191–3206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somner E. A.; Reynolds P. E. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1990, 34, 413–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm J. S.; Chen L.; Walker S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13970–13971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo M. C.; Men H.; Branstrom A.; Helm J.; Yao N.; Goldman R.; Walker S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 3540–3541. [Google Scholar]

- Cudic P.; Kranz J. K.; Behenna D. C.; Kruger R. G.; Tadesse H.; Wand A. J.; Veklich Y. I.; Weisel J. W.; McCafferty D. G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 7384–7389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breukink E.; de Kruijff B. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2006, 5, 321–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T.; Sahl H. G. Curr. Opin. Invest. Drugs 2010, 11, 157–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somma S.; Merati W.; Parenti F. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1977, 11, 396–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brötz H.; Bierbaum G.; Leopold K.; Reynolds P. E.; Sahl H. G. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 154–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brötz H.; Josten M.; Wiedemann I.; Schneider U.; Götz F.; Bierbaum G.; Sahl H. G. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 30, 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann I.; Bottiger T.; Bonelli R. R.; Wiese A.; Hagge S. O.; Gutsmann T.; Seydel U.; Deegan L.; Hill C.; Ross P.; Sahl H. G. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 61, 285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann I.; Bottiger T.; Bonelli R. R.; Schneider T.; Sahl H. G.; Martinez B. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 2809–2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee C.; Paul M.; Xie L.; van der Donk W. A. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 633–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garneau S.; Martin N. I.; Vederas J. C. Biochimie 2002, 84, 577–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S. M.; O’Connor P. M.; Cotter P. D.; Ross R. P.; Hill C. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2606–2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClerren A. L.; Cooper L. E.; Quan C.; Thomas P. M.; Kelleher N. L.; van der Donk W. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 17243–17248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton E. M.; Cotter P. D.; Hill C.; Ross R. P. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007, 267, 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin N. I.; Sprules T.; Carpenter M. R.; Cotter P. D.; Hill C.; Ross R. P.; Vederas J. C. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 3049–3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann N.; Jung G. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 246, 809–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekat C.; Jack R. W.; Skutlarek D.; Farber H.; Bierbaum G. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 3777–3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Walker D.; Sun B.; Hu Y.; Walker S.; Kahne D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003, 100, 5658–5663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekkelenkamp M. B.; Hanssen M.; Hsu S. T. D.; de Jong A.; Milatovic D.; Verhoef J.; van Nuland N. A. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 1917–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortvedt C. I.; Nissen-Meyer J.; Sletten K.; Nes I. F. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 1829–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A. C.; Liu H.; Pattabiraman V. R.; Vederas J. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 462–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict R. G.; Dvonch W.; Shotwell O. L.; Pridham T.; Lindenfelser L. A. Antibiot. Chemother. 1952, 2, 591–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The target of cinnamycin is believed to be phosphatidylethanolamine (see: ; Märki F.; Hanni E.; Fredenhagen A.; van Oostrum J. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1991, 42, 2027–2035). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; However, a recent report suggests that it also induces strong cell wall stress (see:; Burkard M.; Stein T. J. Microbiol. Methods 2008, 75, 70–74), prompting the investigation of its inhibition of PBP1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oman T. J.; Boettcher J. M.; Wang H.; Okalibe X. N.; van der Donk W. A. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 78–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L. E.; McClerren A. L.; Chary A.; van der Donk W. A. Chem. Biol. 2008, 15, 1035–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oman T. J.; van der Donk W. A. ACS Chem. Biol. 2009, 4, 865–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Helm J. S.; Chen L.; Ye X. Y.; Walker S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 8736–8737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The experiments reported here were performed on a truncated lipid II analogue in the absence of a membrane environment. Although we find it unlikely that the nanomolar binding affinity with 2:1 stoichiometry will not translate to lipid II embedded in a bacterial membrane, additional studies will be needed to confirm this hypothesis.

- Hasper H. E.; de Kruijff B.; Breukink E. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 11567–11575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A Kd of 14 nM was calculated by fitting the kinetic data to an equation for substrate depletion with a 2:1 binding stoichiometry (see the Supporting Information). The data could not be fit to a 1:1 binding model.

- van der Meer J. R.; Rollema H. S.; Siezen R. J.; Beerthuyzen M. M.; Kuipers O. P.; de Vos W. M. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 3555–3562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L.; Miller L. M.; Chatterjee C.; Averin O.; Kelleher N. L.; van der Donk W. A. Science 2004, 303, 679–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uguen P.; Hindré T.; Didelot S.; Marty C.; Haras D.; Le Pennec J. P.; Vallee-Rehel K.; Dufour A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 562–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corvey C.; Stein T.; Dusterhus S.; Karas M.; Entian K. D. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 304, 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P.; Qi F. X.; Novak J.; Krull R. E.; Caufield P. W. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001, 195, 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furgerson Ihnken L. A.; Chatterjee C.; van der Donk W. A. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 7352–7363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.