More that 9000 deaths in Canadian men and women were attributed to colorectal cancer (CRC) in 2010. Although screening for CRC has been shown to reduce mortality rates and, by extension, confer public health benefits, colonoscopy – one of the preferred diagnostic tests – can cause harm. Ensuring high-quality CRC screening involves the systematic evaluation of services, process improvement and ongoing appraisal. This article describes the steps taken by the authors in establishing a comprehensive quality assurance program in a nonhospital endoscopy unit located in Calgary, Alberta.

Keywords: Benchmarking, Colonoscopy, Colorectal cancer, Patient satisfaction, Quality assurance, Quality indicators

Abstract

Quality assurance (QA) is a process that includes the systematic evaluation of a service, institution of improvements and ongoing evaluation to ensure that effective changes were made. QA is a fundamental component of any organized colorectal cancer screening program. However, it should play an equally important role in opportunistic screening. Establishing the processes and procedures for a comprehensive QA program can be a daunting proposition for an endoscopy unit. The present article describes the steps taken to establish a QA program at the Forzani & MacPhail Colon Cancer Screening Centre (Calgary, Alberta) – a colorectal cancer screening centre and nonhospital endoscopy unit that is dedicated to providing colorectal cancer screening-related colonoscopies. Lessons drawn from the authors’ experience may help others develop their own initiatives. The Global Rating Scale, a quality assessment and improvement tool developed for the gastrointestinal endoscopy services of the United Kingdom’s National Health Service, was used as the framework to develop the QA program. QA activities include monitoring the patient experience through surveys, creating endoscopist report cards on colonoscopy performance, tracking and evaluating adverse events and monitoring wait times.

Abstract

L’assurance de la qualité (AQ) est un processus qui inclut l’évaluation systématique d’un service, l’adoption d’améliorations et une évaluation constante pour s’assurer que des changements efficaces ont été adoptés. L’AQ est un volet fondamental de tout programme organisé de dépistage du cancer colorectal. Cependant, elle devrait jouer un rôle tout aussi important en matière de dépistage opportuniste. La mise sur pied des processus et des démarches en vue d’adopter un programme d’AQ complet peut se révéler un défi de taille pour une unité d’endoscopie. Le présent article décrit les étapes prises pour mettre sur pied un programme d’AQ au Forzani & MacPhail Colon Cancer Screening Centre de Calgary, en Alberta, un centre de dépistage du cancer colorectal et une unité d’endoscopie non hospitalière vouée à exécuter des coloscopies liées au dépistage du cancer colorectal. Les leçons tirées de l’expérience des auteurs pourraient être utiles à d’autres qui voudront créer leur propre projet. L’échelle d’évaluation globale, un outil d’évaluation et d’amélioration de la qualité préparé par les services d’endoscopie intestinale du National Health Service du Royaume-Uni, a servi de cadre pour élaborer le programme d’AQ. Les activités d’AQ incluaient la surveillance de l’expérience des patients au moyen de sondages, la création de cartes de compte rendu des endoscopistes sur le rendement de la coloscopie, le suivi et l’évaluation des effets indésirables et la surveillance des temps d’attente.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most common cause of cancer death in Canadian men and women, resulting in 9100 deaths in 2010 (1). Screening for CRC is effective at reducing CRC mortality (2) and, therefore, has a clear public health benefit. Screening for CRC is currently recommended for all Canadians 50 to 74 years of age (3).

Colonoscopy is integral to CRC screening. First, colonoscopy is the preferred diagnostic test following a positive screening test, such as a fecal occult blood test (FOBT). Second, colonoscopy is the preferred screening test for individuals who are at increased risk for CRC. Third, colonoscopy may also be used as the primary screening test for individuals who are at average risk. Finally, colonoscopy is used for ongoing surveillance of individuals following removal of an adenomatous polyp or CRC.

Cancer screening can result in harm, which is concerning because individuals undergoing screening are otherwise healthy and usually at low risk for the cancer of interest. Colonoscopy can lead to harm if it is inaccurate, unpleasant for the patient or leads to serious adverse events. Therefore, to maximize the potential benefits and minimize the potential harms of CRC screening, it is important to ensure that screening-related colonoscopy is of the highest quality. Providing quality colonoscopy services implies the provision of safe, accurate and patient-centred services.

Quality assurance (QA) is a process that includes the systematic evaluation of a service, institution of improvements and ongoing evaluation to ensure that effective changes were made. QA is a fundamental component of any organized CRC screening program (4). However, it should play an equally important role in opportunistic screening (3). Establishing the processes and procedures for a comprehensive QA program can be a daunting proposition for an endoscopy unit. In the present article, we describe the steps we have taken to establish a QA program at the Forzani & MacPhail Colon Cancer Screening Centre (CCSC), a colorectal cancer screening centre and nonhospital endoscopy unit located in Calgary (Alberta) that is dedicated to providing CRC screening-related colonoscopies. Lessons drawn from our experience may help others develop their own initiatives.

CCSC CLINICAL PROCESSES

The CCSC is an Alberta Health Services (AHS) facility that provides services as part of Alberta’s publicly funded health care system. It opened in January 2008. The CCSC accepts referrals for asymptomatic, generally healthy individuals eligible for CRC screening-related colonoscopy. This includes colonoscopy for the diagnostic investigation of a positive FOBT, screening colonoscopy for those at average or increased risk of CRC, and surveillance colonoscopy for those with a history of adenomatous polyps or CRC. The CCSC does not provide colonoscopy for the investigation of symptoms or for dysplasia surveillance in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

New referrals are triaged by trained nurses. Individuals are first seen at the CCSC for a preassessment visit. This visit includes an education component about CRC, options for screening and preparation for colonoscopy, followed by a one-on-one counselling and medical assessment session performed by a trained nurse.

All colonoscopies are performed by gastroenterologists or colorectal surgeons who must also maintain active privileges and perform endoscopy at a Calgary acute care hospital. All procedures are performed using Pentax (Pentax, Japan) high-definition colonoscopes. Most procedures are performed with conscious sedation using a combination of fentanyl and midazolam; however, some are performed without sedation at the patient’s request. Propofol is not used at the CCSC. Endoscopy reports are generated at the completion of the procedure, with a copy of the report and lay summary provided to patients at the time of discharge. Pathology reports are reviewed by trained nurses who make ongoing screening and surveillance recommendations based on an evidence-based algorithm.

CCSC data resources

The CCSC uses two main databases to support its QA reporting. The databases are located on the secure AHS network. The collection and use of data are governed by AHS privacy guidelines.

Pentax Endopro:

This data management software supports patient scheduling, image capture and generation of structured endoscopy reports (Doc-U-Scribe) using drop-down menus and free text entry. Routinely entered information includes procedure indication, quality of bowel preparation, depth of insertion, endoscopic findings, and interventions and endoscopist recommendations. The nursing notes add-on module is used to record patient information on the day of colonoscopy. Routinely collected information includes data regarding bowel preparation, vital signs, sedation, reversal agents and specimens. Endopro data are retained within a searchable database. Data can be exported in various formats, including Excel (Microsoft Corporation, USA) spreadsheets, using Endopro’s database reporting tools. Data can also be directly extracted from Endopro database tables using structured query language software and custom search strategies.

CCSC referral management database:

This Access database (Microsoft Corporation, USA) is used to track patients from receipt of referral to completion of colonoscopy. The database includes date of referral, date of preassessment visit, date of colonoscopy, referral triage priority and demographic information about the patient. In addition, the database is also used to record a summary of a patient’s pathology report.

QA framework: Global Rating Scale

The Global Rating Scale (GRS) was created as a quality assessment and improvement tool for the gastrointestinal endoscopy services of the National Health Service in the United Kingdom (UK) (5). The GRS divides the patient experience into two dimensions: clinical care and quality of patient experience. The clinical care domain includes six items: appropriateness, information/consent, safety, comfort, quality of the procedure and timely results. The quality of patient experience dimension also includes six items: equality, timeliness, choice, privacy and dignity, aftercare and ability to provide feedback. For each item, criteria indicate what is required for an endoscopy unit to achieve a rating from D (basic service) to A (excellent service with fully established QA processes).

In November 2006, the CCSC leadership held a QA retreat. The retreat was attended by seven gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons who provided colonoscopy screening, three gastroenterology residents, two administrators responsible for gastroenterology endoscopy services, a senior endoscopy nurse, a general internist responsible for QA activities in the Calgary Health Region, a representative from the University of Calgary’s legal services and members of the CCSC planning committee. Dr Roland Valori attended as an invited guest. Dr Valori developed and implemented the GRS during his tenure as endoscopy lead within the UK’s National Health Service. Attendees agreed that the GRS should provide the framework for the CCSC’s QA program. Participants worked to modify the wording of the GRS items and explanatory text for use at the CCSC. No substantial changes to the recommended benchmarks or criteria were made, apart from making wait-time benchmarks congruent with those recommended by the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (6).

The GRS criteria for an excellent service were then used to guide the development of the CCSC’s QA program. The monitoring and evaluation processes expected of excellent endoscopy units include obtaining patient input on various aspects of care, monitoring clinical outcomes and adverse events, and maintaining a wait-list management system. The following sections describe the processes implemented at the CCSC to achieve these goals.

Patient experience surveys

Surveys were used to obtain feedback from a large number of patients on their colonoscopy experience. A prototype questionnaire was selected from several patient questionnaires available from the knowledge management system area of the GRS website (5). The questionnaire was modified and subsequently pilot tested on several patients at the CCSC. The final five-page questionnaire included 41 close-ended and two open-ended questions. The questionnaire included items pertaining to the patient’s experience at the preassessment visit, on the day of the colonoscopy and with aftercare. There were items regarding the information the patient received about CRC screening and colonoscopy, interactions with CCSC staff and physicians, privacy and dignity, and satisfaction with the procedure.

The final version of the questionnaire was formatted to a machine-readable data form. The questionnaire, along with a business reply envelope, was distributed at discharge from the endoscopy unit to 1000 consecutive patients from March to June 2008. Completed questionnaires were returned by 629 patients.

Subsequent patient-experience surveys were completed in 2009 and 2010. For the 2009 survey, the questionnaire was revised based on the responses, particularly the written comments, to the 2008 survey. The survey was expanded to 10 pages. Items pertaining to bowel preparation and intravenous catheter insertion were added. The items pertaining to the tolerability of the colonoscopy were revised and expanded to include four items (Table 1). In addition, the physician performing the colonoscopy was identified in the questionnaire to enable physician-specific reporting. The revised questionnaire was distributed to 650 patients in 2009, and 350 participants in 2010, with a response rate similar to the 2008 survey.

TABLE 1.

Patient comfort ratings from the 2009 Patient Experience Survey

| Do you think you received the right amount of sedation? | Response, % |

|---|---|

| Yes | 88 |

| No, I would have tolerated the procedure better if I received more sedation | 7 |

| No, I think I would have tolerated the procedure just as well with less sedation | 5 |

|

On the scale below, please mark your overall assessment of the level of discomfort you experienced during the colonoscopy | |

| No discomfort | 45 |

| Mild discomfort | 35 |

| Moderate discomfort | 15 |

| Severe discomfort | 4 |

|

On the scale below, please mark if the colonoscopy experience was worse, better or as you expected | |

| Worse than expected | 6 |

| As expected | 33 |

| Better than expected | 60 |

|

Overall, how acceptable did you find your colonoscopy? | |

| Procedure was acceptable and I would have it again if necessary | 90 |

| Procedure was acceptable, but uncomfortable. I would only have it again if essential | 10 |

| Procedure was totally unacceptable. I would not have the procedure again | 0.25 |

Overall, the questionnaire results showed very high levels of satisfaction with the experience of undergoing a colonoscopy at the CCSC. The vast majority of negative comments were related to bowel preparation. After each survey, the CCSC Executive Committee reviewed the results and, where appropriate, took specific actions (Table 2). A written report was provided to all staff and endoscopists, and was made available to patients in the CCSC’s waiting room and on the CCSC website. A sample of written comments, both positive and negative, was provided to all nursing and clerical staff. Because the comments were overwhelmingly positive and often identified individual nurses, it provided a significant boost to staff morale and esteem.

TABLE 2.

Examples of written feedback provided by patients as part of the Patient Experience Survey

| Representative feedback | Action taken |

|---|---|

| When phoning to check how to use the Pico Salax*, I had to hold for 25 min | Introduction of automated telephone answering system directing callers to specific staff based on nature of inquiry |

| I was put on hold forever! | |

| In written material, CoLyte† is mentioned. I used an alternative. Might be brand name difference, but material should be clear | Instructions sheets revised to include all formulations of PEG-based bowel preparations |

| The preparation document should indicate alternatives to CoLyte, because it is hard to find at Calgary (Alberta) pharmacies | |

| It was great. Other than the fact it was hard to get the IV line in | Specific questions about IV insertion added to survey |

| It took 3 painful attempts | Additional in-service training of nursing staff |

IV Intravenous; PEG Polyethylene glycol.

Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc, Canada;

Alaven Pharmaceuticals LLC, USA

There are costs associated with performing a patient survey including the costs of the questionnaire and business reply envelopes, postage and questionnaire scanning. At the CCSC, data analysis and the creation of reports were performed by one of the authors. In other settings, modest additional costs may be required for these tasks. Unless the questionnaire is substantially revised for each use, the costs of creating the questionnaire for subsequent surveys are minimal.

Endoscopist report cards

Participation in the quality monitoring program is a requirement for endoscopy privileges at the CCSC. The CCSC provides each endoscopist with an annual report card on their colonoscopy performance. The CCSC uses patient surveys, nurse-completed patient comfort forms and routinely collects clinical indicators to monitor colonoscopy quality.

The first set of endoscopist report cards was prepared in January 2009 based on procedures performed in 2008. There were three sections to the report card: completeness of Endopro reporting; sedation practices; and procedure quality indicators. The completeness of Endopro reporting indicated the percentage of cases in which procedure indication and findings were not entered using the drop-down menus. Sedation practices reported the proportion of procedures performed with no sedation, the proportion of procedures requiring reversal agents, and the average dose of fentanyl and midazolam. Procedure quality indicators included the cecal intubation rate, polyp detection rate and average withdrawal time. Polyp detection rate was defined as the proportion of cases in which a polyp was removed. This indicator was used instead of the adenoma detection rate because it could be calculated with the data available from the endoscopy reporting system. Withdrawal time was measured using data captured in Endopro nursing notes. Endoscopy nurses were instructed to record vital signs when the cecum was reached and when the colonoscope was withdrawn from the rectum. These data were then used to calculate the withdrawal time for each procedure. The average withdrawal time was calculated for procedures in which no polypectomy was recorded by either the physician or the nurse.

The reports were created by extracting the required data from Endopro using the system’s database reporting tools. The extracted data were then imported into statistical software that calculated quality indicators at the endoscopist and centre level. The results were subsequently exported to an Excel spreadsheet to allow for a Word mail merge (Microsoft Corporation, USA) to create each endoscopist’s report. The report also provided each endoscopist with the CCSC average for each indicator and their quartile ranking among all endoscopists at the CCSC for selected indicators.

It is important to validate the quality results obtained from electronic database queries, particularly when endoscopist performance is at issue. In the first set of reports, outliers were identified and studied to ensure that the results obtained were accurate. This review process helped to identify that endoscopists could obtain false results if they used free text data entry instead of defined drop-down menus during endoscopy report generation. The database queries and methodologies were further validated using an external database engine and an independent analysis to ensure the reproducibility and accuracy of the quality reports.

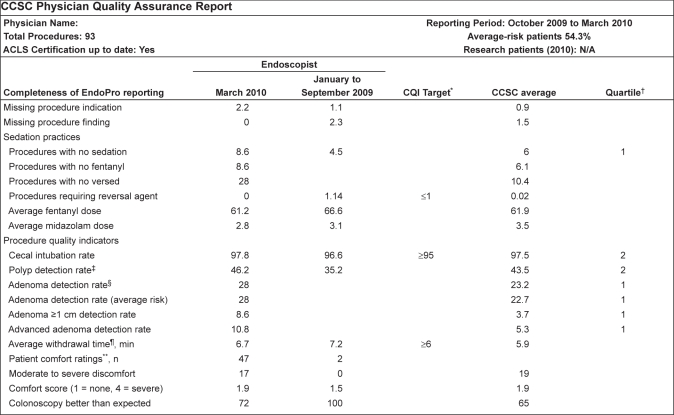

A second physician report card was distributed in October 2009 based on procedures performed from January to June 2009. This report card used the same indicators, but also included patient comfort ratings. These scores were obtained from the patient-completed Patient Experience Surveys and a separate Patient Comfort Questionnaire, which included the same questions on procedural tolerance and comfort. A third report card was distributed in April 2010 based on procedures performed from October 2009 to March 2010 (Figure 1). This report card included various measures of adenoma detection rate, including overall adenoma detection rate, adenoma detection rate in average-risk individuals, detection rate of adenomas >1 cm in size and advanced adenoma detection rate. Data regarding adenomas were obtained from the pathology summary recorded in the CSCC Referral Management database. The first two reports used the Endopro database reporting tools to extract the required data. For the final report, structured language queries that directly extracted the required data were created.

Figure 1).

Physician report card. Data are representative and presented as % unless otherwise indicated. *Continuous quality improvement (CQI) targets: United States Multisociety Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1296–308; †Quartiles are calculated only if 30 or more procedures performed during a reporting period: 1 = Top performing quartile, 4 = Bottom performing quartile; ‡Polyp detection rate is based on findings entered using Endopro Finding drop-down menu; §Adenoma detection rates are based on pathology reports; ¶Average withdrawal time is calculated from procedures in which no polyps are reported in Endopro (Pentax, Japan) Findings menu; **From patient comfort score questionnaires (n = number of responses for the endoscopist). CCSC Colon Cancer Screeing Centre; N/A Not available

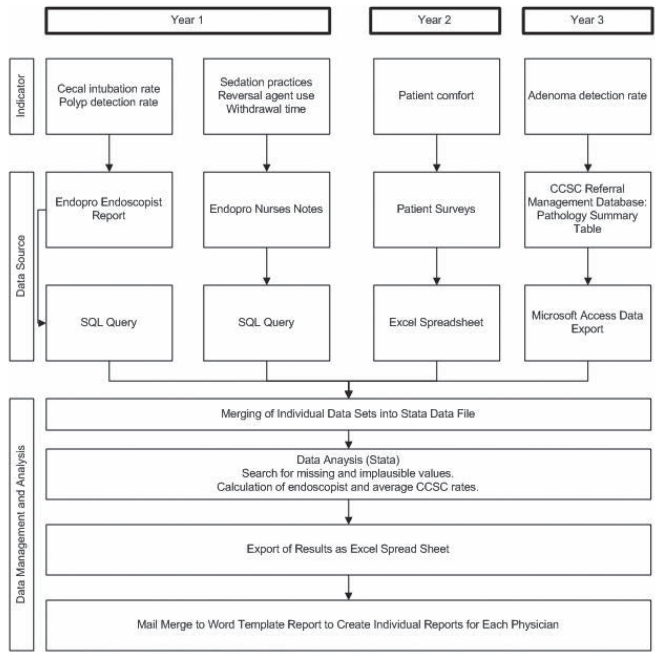

There were no direct costs to the CCSC in the preparation of physician report cards because database extracts, data linkages, and analysis and preparation of reports were performed by two of the authors. The complexity of each report, and the required data elements and data sources, was increased with each version of the questionnaire (Figure 2).

Figure 2).

Evolution of data collection processes for creation of physician report cards. CCSC Colon Cancer Screening Centre; EndoPro (Pentax, Japan); Access, Excel and Word (Microsoft Corporation, USA); SQL Structured query language

Adverse events

Before the CCSC opened, a policy and procedure on reporting harms was developed and approved by the CCSC Executive Committee. The policy defined reportable adverse events, which included administration of reversal agents, adverse events requiring transfer to a hospital emergency room and adverse events occurring after discharge from the CCSC. The CCSC was often informed about delayed adverse events, such as postpolypectomy hemorrhage, by hospital endoscopists or by the patient. In the written instructions provided at the time of discharge from the CCSC, patients were asked to call the CCSC if they had an unexpected hospital admission or emergency department visit within 30 days of the colonoscopy. Adverse events were recorded in an adverse event log. Each adverse event was investigated by the clinical operations manager and the medical director.

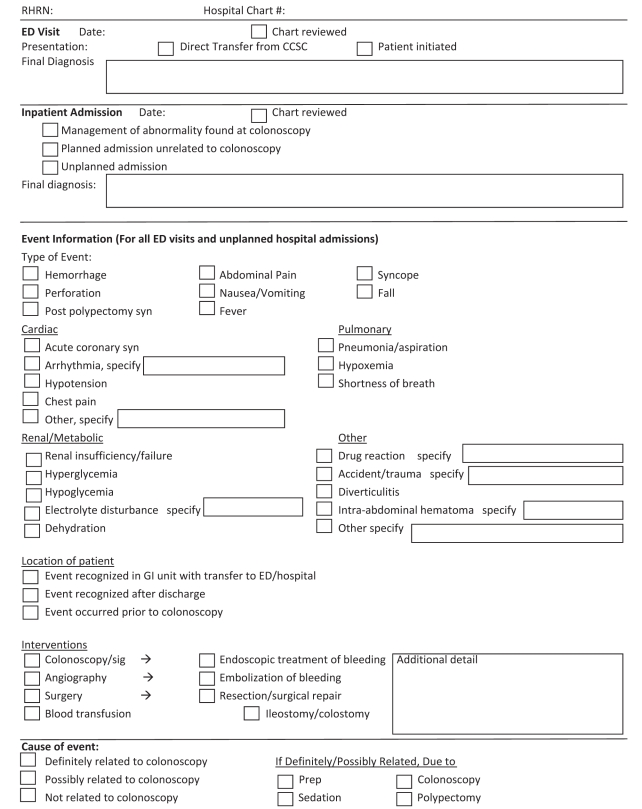

Due to the risk of missing adverse events occurring after discharge from the CCSC, a method for identifying these events was developed by linking patient lists from Endopro with two of AHS’s administrative databases, which enabled the identification of emergency room visits and inpatient admissions occurring two days before or within 30 days of a scheduled colonoscopy. This time frame was used to capture events that occurred during bowel preparation that may have resulted in the patient missing their colonoscopy appointment. All charts of patients with an emergency room visit or inpatient admission were reviewed by a trained research assistant using a structured data collection form (Figure 3). All emergency room visits and unexpected inpatient admissions were classified as unrelated, possibly or definitely related to the colonoscopy by one of the authors.

Figure 3).

Structured data collection form for reviewing charts of patients with a suspected adverse event following colonoscopy. CCSC Colon Cancer Screening Centre; ED Emergency department; GI Gastrointestinal; Prep Preparation; RHRN Regional health records number; sig Sigmoidoscopy; syn Syndrome

The major costs for the identification of adverse events that were not directly reported to the CCSC were those related to hospital chart reviews. For the first 16,000 CCSC patients, approximately 300 emergency room visits and 100 hospital admissions were identified. The time to review each chart is usually quite short because most were emergency room charts with only one or two relevant pages to review. Because the review was performed as part of a QA activity, the hospitals did not require ethics committee approval or charge a chart access fee as would occur with a research-based review.

Wait times

The GRS requires that endoscopy units have a wait-list management system. The GRS also sets wait-time benchmarks for urgent and routine procedures.

The CCSC referral management database was used to regularly monitor wait times. A more detailed wait-time report was created by extracting information pertaining to the number of new referrals awaiting appointments and wait times from date of referral to date of preassessment visit, and importing it from the database into statistical software that summarized statistics and prepared graphs. Wait-list and wait-time information was reported for all referrals and for each referral priority category. The CCSC uses the following four priority categories: highly urgent priority includes patients with a positive FOBT; urgent priority includes patients with a strong family history of CRC (single first-degree relative diagnosed before 60 years of age, or more than one first-degree relative); moderate priority includes patients with a family history of CRC who do not fulfill the criteria for urgent priority; and routine priority includes all individuals at average risk for CRC. The predefined wait-time goals for the CCSC were based on benchmarks set by the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (6).

Wait times for all procedures, other than routine (ie, average risk) referrals, decreased substantially during the first 18 months of operations. Long wait times during the first 18 months were due to several factors that included the following:

A substantial regional wait list of patients already in existence at the time of opening;

A high daily referral volume (150 to 200 referrals);

The CCSC opened with an electronic medical record and referral management system that quickly proved to be inadequate; and

An insufficient number of clerical staff and inadequate referral management and triage processes to deal with the higher than anticipated daily referral volume in addition to a large referral backlog.

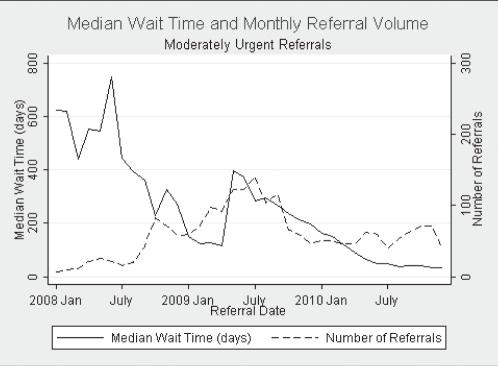

As these limitations and barriers to effective triage and scheduling were resolved, wait times dramatically declined to an acceptable level for all nonroutine referrals (Figure 4).

Figure 4).

Median wait time and monthly referral volume for moderate priority referrals. Jan January

Routinely monitoring wait lists and wait times is essential for maximizing patient care and ensuring a highly productive endoscopy service. After the identification of long wait times for patients at average risk for CRC, the CCSC instituted an FOBT strategy for this group in which the patient was sent an FOBT requisition by mail; their referring physician was informed of the long wait time and requested to ensure that the patient completed an FOBT annually.

GRS RATINGS: ASSESSING THE SUCCESS OF QA ACTIVITIES

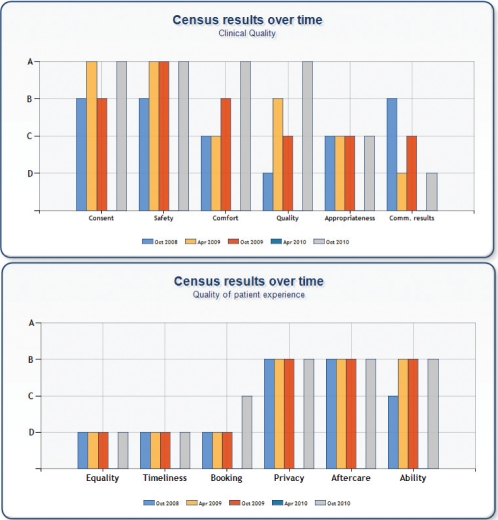

The CCSC reported results to the Canadian GRS census four times between October 2008 and October 2010 (Figure 5). The Canadian GRS census uses the version of the GRS developed by the CCSC. The CCSC has achieved A-level ratings on the items for consent, comfort, safety and quality. The lowest ratings have been for three items in the quality of patient experience: equality, timeliness and booking. The CCSC received a low rating for equality because it did not have a demographic/language profile of the local population, nor did it have written information available in languages other than English. The CCSC did not achieve the minimum standard for timeliness in the GRS: “Waits are <8 weeks for urgent procedures and <52 weeks for routines.” However, this may be an example in which consistent intercountry definitions are lacking. It is unlikely that ‘routine’ in the UK refers to average-risk screening colonoscopy because that service is not provided by the National Health Service. The CCSC’s low rating on booking also likely reflects wording that is specific for the UK. For example, one criteria for the C level is that “>50% of new referrals are directly booked”. The meaning of ‘directly booked’ is not clear and not clearly relevant to the CCSC.

Figure 5).

Colon cancer screening centre global rating scale census results. Apr April; Comm Communicating; Oct October

DISCUSSION

Using the GRS as a framework, the CCSC has been able to develop and implement a comprehensive QA program. Key quality indicators are routinely measured to ensure that the services provided and the patient experience are of the highest quality. QA activities have been gradually expanded over the first three years of the CCSC’s operations as resources and available data have allowed. The key components of the QA program include regular surveys of patient experience, measurement and reporting of endoscopist performance, identification and investigation of adverse events and tracking of wait lists and wait times. We observed that a few GRS statements did not directly apply to our context. However, its use provided focus and maintained engagement and momentum, which are critically important for effective change to occur.

QA activities at the CCSC are facilitated by the collection of unbiased data using an electronic reporting system (Endopro), which is modified to allow entry of QA data as part of the routine clinical operations of the facility. A notable example of this is the routine recording of vital signs at the time of cecal intubation and withdrawal from the rectum, which enable the calculation of withdrawal time. Because data entry is part of routine clinical practice, it is entered in real-time, missing data are minimized and additional resources are not required for their collection. In addition, the reporting templates within Endopro were modified to maximize the consistent and standardized reporting of key clinical outcomes using drop-down menus to facilitate subsequent database queries and analysis.

The feasibility of a comprehensive QA program would be limited in the absence of searchable clinical databases. The need for manual data entry from paper clinical charts would greatly increase the cost of data collection. The existing databases, however, have significant limitations. For example, Endopro allows three methods of data entry: the use of drop-down menus; free-text fields during report creation; and revision of any aspect of the report, similar to a word processor, while previewing the report before saving and printing. Only data recorded with the first two methods are included in the database, and only the data recorded with the drop-down menus are suitable for the generation of automated QA reports. The CCSC QA reporting maximized the usefulness of Endopro data by including completeness of use of drop-down menus as an item in the endoscopist report cards.

Although routinely collected clinical data supports the measurement of colonoscopy quality indicators, dedicated data collection is required to assess patient experience. Multiple patient satisfaction questionnaires are available in the public domain and can be obtained from the GRS website or through an Internet search. These questionnaires provide a good starting point from which an endoscopy unit can design a survey tailored to its own needs. There is a lack of well-validated scales for measuring some aspects of the patient experience (eg, comfort and tolerability of bowel preparation). In collaboration with Drs Roland Valori, Matt Rutter and Thomas Lee of the UK’s National Health Service, we recently developed a validated patient comfort tool that is scored by the endoscopy room nurse at the completion of the procedure (7).

There are several barriers to implementing a comprehensive QA program. First, endoscopy units have limited resources to expend on activities that do not provide clinical services, which can be one more challenge for already over-burdened managers. Second, there may be a lack of buy-in by nursing staff and endoscopists. Finally, required data may be absent or difficult to access.

Despite these barriers, we have witnessed several early wins from our QA activities. For the nursing and clerical staff, regularly receiving positive feedback from patients is a source of pride, which promotes their support of other QA activities that require their time. Endoscopists have appeared to genuinely appreciate receiving high-quality reports on the care they provide, and patients clearly appreciate that their views are being sought. The high response rate to our surveys demonstrates that patients want to have a voice in how health care is delivered to them. Therefore, the time, effort and resources required to operate a comprehensive QA program is rewarded by the high levels of patient satisfaction with the clinical services and the knowledge that the CCSC provides high-quality colonoscopy services. Given the benefits to patient care and staff satisfaction results from QA activities, the allocation of adequate resources should be a priority for all endoscopy units.

The stated goal of AHS is to “achieve a patient-focused system – one in which Albertans are satisfied with the quality of the health-care services they receive” (8). Our QA program has helped us achieve this at the CCSC. Our goals for the future are to support QA processes at hospital endoscopy units and within a future provincial screening program. The set of QA tools that we developed is readily transferable to other units and jurisdictions. A comprehensive QA program is critical in providing safe, high-quality and efficient colonoscopy services.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Cancer Institute of Canada . Canadian Cancer Statistics 2010. Toronto: National Cancer Institute of Canada; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, Towler B, Irwig L. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): An update. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1541–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leddin DJ, Enns R, Hilsden R, et al. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology position statement on screening individuals at average risk for developing colorectal cancer: 2010. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:705–14. doi: 10.1155/2010/683171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segnan N, Patnick J, von Karsa L, editors. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Endoscopy Global Rating Scale (GRS), 2011. <www.globalratingscale.com> (Accessed on March 23, 2011).

- 6.Paterson WG, Depew WT, Pare P, et al. Canadian consensus on medically acceptable wait times for digestive health care. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:411–23. doi: 10.1155/2006/343686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross E, Dube C, Hilsden R, et al. Development and prospective evaluation of a nurse assessed patient comfort scale (NAPCOMS) for colonoscopy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:85A. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Highlights. Edmonton: Alberta Health and Wellness/Alberta Health Services; 2010. Becoming the Best: Alberta’s 5-year Health Action Plan 2010–2015. [Google Scholar]