A significant proportion of the developing world’s population and more than one-third of the developed world’s population are infected with Helicobacter pylori – a Gram-negative bacterium classified as a WHO class I carcinogen that has also been associated with nonmalignant gastrointestinal diseases. Trials investigating several treatment regimens have reported H pylori eradication rates of 70% to 90%. However, despite the potentially serious health sequelae associated with H pylori infection, data regarding the effectiveness of eradication treatment in usual practice are lacking. Accordingly, this study aimed to determine the rates of appropriate treatment and the clinical course of patient follow-up in usual practice at a major academic health sciences centre in Toronto, Ontario.

Keywords: Endoscopy, Follow-up, Helicobacter pylori, Inpatients, Outpatients, Treatment

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Helicobacter pylori is a WHO class I carcinogen also associated with nonmalignant gastrointestinal diseases. Effective treatment exists, and all persons infected with H pylori should receive treatment. However, data regarding the rates of treatment prescription in clinical practice are lacking.

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the rates of H pylori treatment in usual practice.

METHODS:

Patients with histological evidence of H pylori infection between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2007, at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (Toronto, Ontario) were identified. Charts were reviewed to determine the rates of H pylori treatment and confirmation of eradication, when indicated. Questionnaires were subsequently sent to endoscopists of patients identified as not having received treatment to determine the reasons for lack of treatment.

RESULTS:

A total of 102 patients were H pylori positive and were appropriate candidates for treatment, of whom 58 (57%) were male and 78 (76%) were outpatients, with 92 (90%) receiving eradication therapy. When indicated, 15 of 22 (68%) patients received confirmation of eradication, 13 of 18 (72%) patients underwent repeat endoscopy and 86% received complete therapy. Outpatients were more likely to receive eradication therapy (OR 10.3 [95% CI 2.6 to 40.4]; P=0.001) and complete therapy (OR 13.2 [95% CI 3.8 to 45.7]; P=0.0001) compared with inpatients. Having a follow-up appointment resulted in higher treatment rates (OR 12.0 [95% CI 3.0 to 47.5]; P=0.001).

CONCLUSION:

During the time period studied, adequate rates of H pylori treatment were achieved in outpatients and patients who had formal follow-up at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. However, some aspects of care remain suboptimal including treatment of inpatients and care following treatment. Additional studies are required to identify strategies to improve the care of patients infected with H pylori.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

L’OMS classe l’Helicobacter pylori comme un carcinogène de groupe I qui s’associe à des maladies gastro-intestinales non malignes. Il existe des traitements efficaces, et toutes les personnes infectées par le H pylori devraient être traitées. Cependant, on ne possède pas de données sur les taux de prescription de traitements en pratique clinique.

OBJECTIF :

Déterminer les taux de traitement du H pylori en pratique régulière.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont recensé les patients qui avaient eu des manifestations histologiques d’infection à H pylori entre le 1er janvier 2007 et le 31 décembre 2007 au Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre de Toronto, en Ontario. Ils ont examiné leur dossier pour déterminer les taux de traitement du H pylori et en confirmer l’éradication, lorsque c’était indiqué. Ils ont ensuite envoyé des questionnaires aux endoscopistes des patients qui, selon les indications, n’avaient pas été traités, afin d’en déterminer les raisons.

RÉSULTATS :

Au total, des 102 patients qui étaient positifs au H pylori et étaient de bons candidats au traitement, 58 (57 %) étaient de sexe masculin,78 (76 %) étaient en consultations externes et 92 (90 %) avaient reçu une thérapie d’éradication. Lorsque c’était indiqué, 15 des 22 patients (68 %) ont reçu une confirmation de l’éradication, 13 des 18 patients (72 %) ont subi une reprise de l’endoscopie et 86 % ont reçu un traitement complet. Les patients en consultations externes étaient plus susceptibles d’avoir reçu une thérapie d’éradication (RRR 10,3 [95 % IC 2,6 à 40,4]; P=0,001) et une thérapie complète (RRR 13,2 [95 % IC 3,8 à 45,7]; P=0,0001) que les patients hospitalisés. Un rendez-vous de suivi s’associait à des taux de traitement plus élevés(RRR 12,0 [95 % IC 3,0 à 47,5]; P=0,001).

CONCLUSION :

Pendant la période à l’étude, on obtenait des taux suffisants de traitement du H pylori chez les patients en consultations externes et ceux qui recevaient un suivi officiel au Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. Cependant, certains aspects des soins demeurent sous-optimaux, y compris le traitement des patients hospitalisés et les soins après le traitement. D’autres études s’imposent pour établir des stratégies afin d’améliorer les soins aux patients infectés par le H pylori.

Up to 70% of the developing world’s population, and up to 30% to 40% of the developed world’s population are infected with Helicobacter pylori, a Gram-negative microaerophilic bacterium (1). H pylori is a WHO class I carcinogen, and is strongly associated with the development of gastric adenocarcinoma and MALT lymphoma. It is also linked to other nonmalignant gastrointestinal diseases including nonulcer dyspepsia and peptic ulcer disease (PUD) (2–4). Eradication of H pylori decreases the recurrence of PUD and may lead to tumour regression in low-grade and localized MALT lymphoma (5,6). On completion of treatment, the American College of Gastroenterology, based largely on expert consensus, recommends confirmation of H pylori eradication in patients with known PUD and/or MALT lymphoma, those with successfully treated early gastric adenocarcinoma and those with persistent nonulcer dyspeptic symptoms (7). Appropriate methods to confirm eradication include urea breath testing or repeat endoscopy with biopsy. Repeat endoscopy to confirm healing of gastric ulcers – regardless of whether they are H pylori-associated – may be indicated due to the risk of concomitant underlying malignancy (8,9). Endoscopic surveillance may improve survival and may be cost effective in high-risk populations in which the prevalence of gastric malignancy is high (10).

Antibiotic plus proton pump inhibitor treatment of H pylori has been shown to be both efficacious and cost effective in randomized controlled trials (5). Large systematic reviews have reported significant rates of PUD healing and decreased recurrence of PUD with eradication therapy (11). Recommended regimens include a proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole for two weeks. Second-line regimens comprise bismuth subsalicylate quadruple therapy regimens. Eradication rates in trials investigating these regimens have ranged from 70% to 90% (7).

However, consistent and recent data regarding the effectiveness of H pylori eradication – defined as treatment of H pylori in ‘usual’ practice – are lacking. In usual clinical practice, involvement of multiple physicians in the care of individual patients, suboptimal communication between providers and inadequate patient follow-up may compromise adherence to H pylori treatment recommendations. Reports of treatment prescription rates have varied from 10% to greater than 90% (12–15). As noted above, once treated with a recognized regimen, confirmation of eradication may be indicated in certain disease states; however, in usual practice, rates of confirmation in the various disease states listed above are not known.

Due to the potential serious health sequelae of untreated H pylori infection, and because large-scale trials have shown efficacy, it is important to determine whether patients found to be infected with H pylori are routinely receiving treatment in usual practice. In the current study, our objective was to determine the rates of receipt of treatment for H pylori among appropriate patients in usual practice at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (SHSC) in Toronto, Ontario. Physician and patient factors associated with receipt of treatment and clinical course following eradication were also explored.

METHODS

The present analysis was a single-centre cohort study of patients with histological evidence of H pylori infection diagnosed between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2007, at SHSC. An English language search of all pathology reports issued during the study period using the words “Helicobacter” and “stomach biopsy” was used to identify eligible patients. Additionally, all reports coded as “stomach biopsy” – a code inclusive of all anatomical sites in the stomach – in the laboratory information system during the study period were retrieved to ensure that cases were not missed due to variation in diagnostic terminology. Pathology reports were then reviewed and only patients with histological evidence of H pylori infection were retained in the cohort.

Hospital charts and endoscopist office charts for all patients in the cohort were reviewed. Data were collected from the clinical notes and endoscopy report, and the pathology report in the charts using a standardized data collection form. From the chart review, patients who did not appear to have received treatment and, where indicated, to have had confirmation of eradication and to have received repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy were identified. The physicians who performed endoscopy on these patients were then asked to review their records to confirm that the patient had not been treated and, where indicated, had not received confirmation of eradication or repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy. If confirmed, the physicians were asked to provide reasons for these apparent lapses in appropriate care.

From the charts, demographic data (age, sex and inpatient/outpatient status), clinical data (medical comorbidities and admission medications [including previous nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug/acetylsalicylic acid use]), endoscopic data (endoscopy indication and endoscopic findings) and pathological diagnoses other than H pylori infection were also abstracted.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Research and Ethics Board of SHSC.

Study definitions

Receipt of eradication therapy for H pylori was defined as clear notation in the hospital or office chart that a standard eradication regimen had been prescribed, or that another physician was informed of the diagnosis and asked to provide treatment. An assumption by the endoscopist that another physician would treat the patient, without written documentation of a direct request, was not considered to be sufficient. Confirmation of eradication was defined as written documentation of any accepted method (upper endoscopy with biopsy or urea breath testing, but not serological testing) to verify cure of H pylori infection. For the purposes of the current study, confirmation of eradication was required only in patients with diagnoses of PUD or MALT lymphoma, while repeat endoscopy was indicated only in cases of gastric ulcer or MALT lymphoma. Complete treatment was defined as a combination of receipt of eradication therapy and confirmation of eradication, if indicated.

Outcomes and statistical analyses

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of appropriate patients in the entire cohort who received eradication therapy. Patients were considered ‘inappropriate’ for treatment and excluded from the cohort if they died before treatment could be prescribed or if their life expectancy was so short that the treating physician believed that treatment was not warranted. Secondary outcome measures were the proportions of appropriate patients who received confirmation of eradication, repeat endoscopy and complete treatment, if indicated.

Depending on the nature of the data, proportions or median values with interquartile ranges were used to describe the baseline characteristics and outcomes of the entire cohort. Similarly, outcomes were assessed in the following subgroups: inpatients versus outpatients, and according to type of follow-up (follow-up appointment with any type of physician versus none; follow-up appointment with gastroenterologist versus any other specialty). ORs with 95% CIs were used to compare subgroups in a univariate fashion, and P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

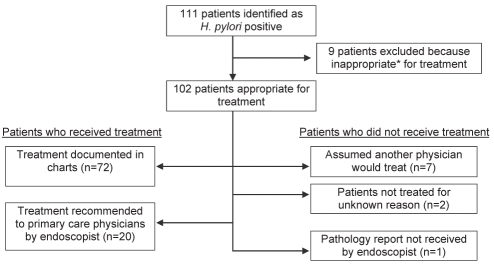

The final cohort comprised 102 patients (Figure 1). Of these, 58 (57%) were male and 78 (76%) were outpatients. The three most common indications for endoscopy were dyspepsia/abdominal pain, anemia and gastrointestinal bleeding (Table 1). Of the entire cohort, 90% received eradication therapy and, when indicated, 68% received confirmation of eradication, 72% received repeat endoscopy and 86% received complete therapy (Table 2).

Figure 1).

Flow diagram of cohort and primary outcome. *Patients were considered to be inappropriate for treatment if they were too ill or had limited life expectancy. H pylori Helicobacter pylori

TABLE 1.

Baseline patient characteristics of the final cohort (n=102)

| Median age, years (interquartile range) | 60 (49–70) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 44 (43) |

| Male | 58 (57) |

| Admission status | |

| Inpatients | 24 (24) |

| Outpatients | 78 (76) |

| Endoscopy indication* | |

| Dyspepsia/abdominal pain (not specified) | 27 (26) |

| Anemia | 17 (17) |

| Melena/hematochezia/hematemesis | 14 (14) |

| Reflux/heartburn | 8 (8) |

| Dysphagia | 6 (6) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 6 (6) |

| Radiological abnormality | 5 (5) |

| Abdominal pain (nondyspepsia) | 5 (5) |

| Weight loss | 5 (5) |

| Other | 16 (16) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Some patients had more than one indication for endoscopy; therefore, total exceeds 100%

TABLE 2.

Outcomes for the entire cohort and patient subgroups

| Received eradication therapy | Confirmation of eradication* | Repeat EGD* | Complete therapy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n=102) | 92/102 (90) | 15/22 (68) | 13/18 (72) | 88/102 (86) |

| Patient type | ||||

| Outpatient (n=78) | 75/78 (96) | 5/7 (71) | 6/7 (86) | 74/78 (95) |

| Inpatient (n=24) | 17/24 (71) | 10/15 (67) | 7/11 (64) | 14/24 (58) |

| Follow-up | ||||

| Any (n=80) | 77/80 (96) | 11/14 (78) | 12/14 (86) | 77/80 (96) |

| GI (n=66) | 65/66 (98) | 8/10 (80) | 8/10 (80) | 65/66 (98) |

| Other† (n=14) | 12/14 (86) | 3/4 (75) | 4/4 (100) | 12/14 (86) |

| None (n=22) | 15/22 (68) | 4/8 (50) | 1/4 (25) | 11/22 (50) |

Data presented as n/n (%).

When indicated as per methods;

Follow-up with family physician, general internist or referring physician. EGD Esophagogastroduodenoscopy; GI Gastrointestinal

In the subgroup analyses, outpatients were more likely than inpatients to receive eradication therapy (OR 10.3 [95% CI 2.6 to 40.4]) and complete therapy (OR 13.2 [95% CI 3.8 to 45.7]). Patients with any follow-up appointment were more likely to receive eradication therapy (OR 12.0 [95% CI 3.0 to 47.5]) and complete therapy (OR 25.7 [95% CI 6.5 to 99.1]) than those without documented follow-up. Patients who had follow-up with a gastroenterologist, as opposed to another physician, were more likely to receive eradication therapy and complete therapy (OR 10.8 [95% CI 1.3 to 88.5]); however, these results were not statistically significant (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

OR of primary and secondary outcomes according to patient subgroup

| Eradication therapy, OR (95% CI) | P | Confirmation of eradication, OR (95% CI) | P | Receiving repeat EGD, OR (95% CI) | P | Complete therapy, OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient type | ||||||||

| Outpatient | 10.3 (2.6–40.4) | 0.001 | 1.2 (0.2–7.5) | 1.00 | 3.4 (0.4–28.1) | 0.6 | 13.2 (3.8–45.7) | 0.0001 |

| Inpatient | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Follow-up | ||||||||

| Any | 12.0 (3.0–47.5) | 0.001 | 3.7 (0.6–22.4) | 0.343 | 18.0 (1.5–197.4) | 0.04 | 25.7 (6.5–99.1) | 0.0001 |

| None | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Type of follow-up | ||||||||

| Gastrointestinal | 10.8 (1.3–88.5) | 0.08 | 1.3 (0.1–15.9) | 1.00 | N/A | 10.8 (1.3–88.5) | 0.08 | |

| Other* | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Follow-up with family physician, general internist or referring physician. EGD Esophagogastroduodenoscopy; N/A Not applicable

DISCUSSION

In the present study of usual clinical practice, approximately 90% of appropriate patients received treatment. Inpatients were less likely to receive eradication therapy and complete treatment. Similarly, we found that patients with formal follow-up were more likely to receive eradication therapy and complete therapy. There was a nonsignificant trend toward receiving eradication therapy and complete therapy in patients who specifically had follow-up with a gastroenterologist. Our study, unlike others in this area, also examined care following H pylori treatment and found that a significant proportion of patients did not receive confirmation of eradication.

Other studies that addressed a similar question have reported varying rates of eradication therapy. A recent study investigating H pylori treatment rates in largely outpatient Asian immigrants (16) reported suboptimal treatment, with rates of 57%. Similarly, an earlier study in Medicare patients in the United States (14) found treatment rates of 53% to 60%. In contrast, one other study from London, Ontario, found higher treatment rates comparable with ours (17).

Certain subgroups may be at risk of suboptimal treatment. We found, as have others (17), that inpatients were at risk of failing to receive treatment. One explanation may be that inpatients, as a whole, tend be more ill than outpatients and have multiple comorbidities. Therefore, other possibly more pressing health issues may take precedence, and treatment of ‘lesser’ conditions, such as H pylori infection, may not be a priority. Second, at our institution, as in many other hospitals, inpatients often undergo endoscopy while admitted under nongastrointestinal physicians for other reasons. At the SHSC, pathology reports are often not available before discharge of a short-stay patient and are routinely sent to the endoscopist only (and not the admitting or family physician). Among the inpatients in our study, only nine of 24 (38%) had reports available before discharge. Conversely, if H pylori infection is determined by serological testing, that result is sent as a hard copy report to the admitting physician and not to the endoscopist. If a formal follow-up appointment with the endoscopist is not arranged, as may be the case for some endoscopists at our institution, treatment of H pylori may be overlooked by the admitting or family physician.

A similar study also confirmed that having a ‘regular doctor’ was associated with higher rates of H pylori treatment completion (16). With a formal follow-up appointment, physicians have the opportunity to ensure that patients have completed their eradication therapy as prescribed and to arrange confirmation of eradication, if indicated. Gastroenterologists, as opposed to other following physicians, might be expected to focus more on gastrointestinal diseases and to treat H pylori infection if present. In our study, the trend toward higher treatment rates in patients who followed up with their gastroenterologists was nonsignificant – probably due to the small sample size.

Although our overall rates of H pylori treatment are reasonable, there is still room for improvement, particularly among certain subgroups such as inpatients. Based on our findings, several quality of care interventions could be considered such as routine follow-up appointments and modifying the way that results are reported or distributed. In terms of the latter, pathology departments may wish to consider mandatory copying of reports to referring and primary care physicians to improve communication and to reduce the likelihood that the result will be overlooked. Increased patient involvement, such as access to one’s own test results on a secure web-based system, might also improve these processes of care. Finally, educational programs for general physicians and gastroenterologists may be useful in addressing the deficiencies we have identified in post-treatment care, including confirmation of eradication and complete therapy, when indicated. Formal evaluation of these quality of care interventions would be useful in identifying practices that can actually be implemented to increase rates of complete therapy.

Because the present analysis was a single-centre study, the generalizability of our results may be in question. However, we believe that the challenges in the treatment of H pylori are common, and that our findings may be applicable to other centres and to other areas of patient care, particularly where procedures and pathology reports are involved. For example, there may be similar deficiencies in the diagnosis and care of patients with other conditions that involve communication between multiple physicians across different locations such as follow-up surveillance colonoscopies after the diagnosis of tubular adenoma or ongoing management of cervical dysplasia.

CONCLUSION

Our one-year analysis at SHSC showed that H pylori treatment rates were good, particularly in the outpatient population and in patients with regular follow-up. However, it is clear that there are opportunities for improvement in the administration of treatment and follow-up of patients with H pylori infection. The lessons learned from H pylori may be applicable to other areas of patient care, especially where conditions are easily identifiable, treatable or preventable. Additional controlled studies are required to identify quality interventions that are effective in ensuring best practices in patients infected with H pylori.

KEY MESSAGES.

Complete treatment of H pylori in usual practice is more likely in outpatients and those with formal follow-up.

Confirmation of eradication, when appropriate, is lacking in a significant proportion of patients.

Opportunities to improve treatment and follow-up of H pylori-positive patients exist, especially in the inpatient population.

REFERENCES

- 1.Everhart JE. Recent developments in the epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2000;29:559–78. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh JH, Peterson WL. The treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in the management of peptic ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:984–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510123331508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paptheodoridis GV, Sougioultzis S, Archimandritis AJ. Effects of Helicobacter pylori and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on peptic ulcer disease: A systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:130–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farinha P, Gascoyne RD. Helicobacter pylori and MALT lymphoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1579–605. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford AC, Delaney BC, Forman D, Moayyedi P. Eradication therapy in Helicobacter pylori positive peptic ulcer disease: Systematic review and economic analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1833–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montalban C, Norman F. Treatment of gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: Helicobacter pylori eradication and beyond. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:361–71. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chey WD, Wong BCY. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hosokawa O, Watanabe K, Hatorri M, et al. Detection of gastric cancer by repeat endoscopy within a short time after negative examination. Endoscopy. 2001;33:301–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-13685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamagata S, Hisamichi S. Precancerous lesions of the stomach. World J Surg. 1979;3:671–3. doi: 10.1007/BF01654785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh JM, Ho W, Hur C. Cost-effectiveness of endoscopic surveillance of gastric ulcers to improve survival. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford AC, Delaney BC, Forman D, Moayyedi P. Eradication therapy for peptic ulcer disease in Helicobacter pylori positive patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD003840. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003840.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roll J, Weng A, Newman J. Diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection among California Medicare patients. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:994–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thamer M, Ray NF, Henderson SC, Rinehart CS, Sherman CR, Ferguson JH. Influence of the NIH Consensus Conference on Helicobacter pylori on physician prescribing among a Medicaid population. Med Care. 1998;36:646–60. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hood HM, Wark C, Burgess PA, Nicewander D, Scott MW. Screening for Helicobacter pylori and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in medicare patients hospitalized with peptic ulcer disease. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:149–54. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirin H, Birkenfeld S, Shevah O, et al. Application of Maastricht 2–2000 guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori among specialist and primary care physicians in Israel: Are we missing the malignant potential of Helicobacter pylori? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:322–5. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200404000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho A, Chaudhry A, Minsky-Primus L, et al. Follow-up care after a diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in an Asian immigrant cohort. J Clin Gastroentorol. 2006;40:29–32. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000190755.33373.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nazareno J, Driman DK, Adams P. Is Helicobacter pylori being treated appropriately? A study of inpatients and outpatients in a tertiary care centre. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:285–8. doi: 10.1155/2007/628408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]