Abstract

Purpose

To bring together information concerning the epidemiology and the economic and individual burdens of glaucoma.

Design

Interpretive essay.

Methods

Review and synthesis of selected literature published from 1991 through December 2010.

Results

An estimated 3% of the global population over 40 years of age currently has glaucoma, the majority of whom are undiagnosed. Vision loss from glaucoma has a significant impact on health-related quality of life even in the early stages of disease. The overall burden increases as glaucomatous damage and vision loss progress. The economic burden of glaucoma is significant and increases as the disease worsens.

Conclusions

Early identification and treatment of patients with glaucoma and those with ocular hypertension at high risk of developing vision loss are likely to reduce an individual's loss of health-related quality of life as well as the personal and societal economic burdens.

Keywords: economic burden, epidemiology, glaucoma, individual burden, health-related quality of life

Glaucoma is a group of chronic eye diseases that irreversibly damages the optic nerve and that can result in serious vision loss and blindness. After cataract, it is the second leading cause of blindness worldwide and is one of the leading causes of preventable blindness.1

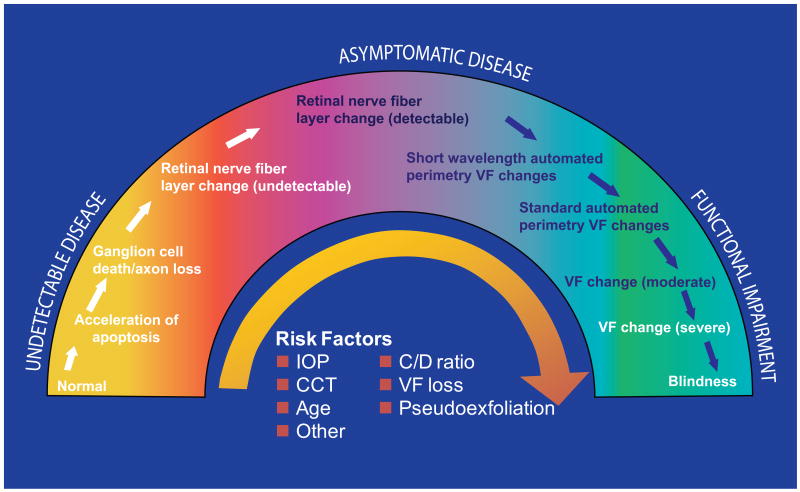

Patients with glaucoma present to eye health professionals with varying severity along a continuum (Figure 1).2 Across much of the continuum, glaucoma damage is relatively asymptomatic because of redundancy in the sensory system and the binocular nature of vision; one eye may compensate for early losses in the other. Major risk factors for developing glaucoma include an elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), greater cup-to-disc ratio, thinner central corneal measurement, older age, and family history for glaucoma.3,4 These and other risk factors also increase the chance of progressive severe disease.

Figure 1.

The glaucoma continuum.2 Reprinted from Am J Ophthalmol; Vol 138; Weinreb RN, Friedman DS, Fechtner RD, et al.; “Risk assessment in the management of patients with ocular hypertension”; pages 458-467. Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier. CCT = central corneal thickness; C/D = cup/disc ratio; IOP = intraocular pressure; VF = visual field.

This essay aims to integrate epidemiologic information with the economic and individual burdens of glaucoma to highlight the impact of glaucoma on individuals, health systems, and societies. We also hope that this information will increase public awareness of glaucoma, will expand professional knowledge of risk factors for visual disability, and will elevate the priority of eye health.

Methods

Publications in English from 1991 through December 2010 on the topics of the epidemiology, economic burden, and individual burden of glaucoma were reviewed. In addition to author identification of important articles, Medline searches (and Embase and IPD for epidemiology) were conducted to identify additional relevant articles using combinations of keywords with “glaucoma” including “prevalence”, “incidence”, “epidemiology”, “cost”, “resource”, and “quality of life”. Searches were intended to serve as the basis for summarizing and integrating important information on the topics of interest and not to meet criteria for a systematic review.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of glaucoma is increasing worldwide (Figure 2).1 Globally, an estimated 60.5 million people (2.65% of the global population over 40) suffered from glaucoma in 2010. Of these, an estimated 44.7 million had primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) and 15.7 million, primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG). The prevalence of glaucoma is expected to reach 79.6 million in 2020, impacting all countries, although the largest increases are expected to be in China and India, which together will represent nearly 40% of cases worldwide. Globally, the number of people with POAG is estimated to reach 58.6 million by 2020, and 21 million will have PACG. More than 4.5 million currently were bilaterally blind from POAG in 2010, a number that is forecasted to rise to 5.9 million by 2020.1

Figure 2.

The prevalence of glaucoma is expected to rise between 2010 and 2020.1

The prevalence of glaucoma, which increases with age and varies by ethnicity,1,5-7 is increasing primarily as the population ages. POAG is most prevalent among people of African descent who have almost 3 times the prevalence compared with white subjects (odds ratio, 2.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.14-3.72).5 After controlling for age and gender, the prevalence of POAG among Latino/Hispanic subjects is comparable to that among black subjects and 3-to-4 fold higher than that observed among white subjects.7 In contrast, PACG is more prevalent in Asian populations, with Asians representing 87% of those with PACG.1

Research in the United States demonstrates the positive relationship between age and prevalence in black, Latino/Hispanic, and white populations.5 For example, the prevalence of POAG among black women in the Baltimore Eye Survey increased from 2.24% among those 50 to 54 years to 5.89% among those ages 70 to 74 years and to 9.82% among those >80 years.5 Among Latinos/Hispanics in the United States, the prevalence of POAG was 16 times higher among those ≥80 years compared with those aged 40 through 49 years and 13 times higher than those aged 50 through 59.7

Because glaucoma frequently is relatively asymptomatic, especially in the early stages, and because there is a low public awareness of glaucoma and its risk factors even in developed societies, the majority of individuals with glaucoma remain undiagnosed (Figure 3).7-11 Many people are not proactive about eye health and remain unaware that they have glaucoma until they experience extensive and usually bilateral visual field loss. Often serendipitous, diagnosis and thus treatment are often delayed. Even among those with diagnosed glaucoma, many do not receive treatment. An analysis of US Medicare claims data from 1992 to 2002 found that an average of 27.4% of beneficiaries with diagnosed POAG did not receive related medical or surgical therapy in a given year.12

Figure 3.

In summary, glaucoma is a major worldwide epidemiological challenge; an estimated 3% of the global population over 40 years of age currently have glaucoma,1 the majority of whom are undiagnosed.7-11 The number of cases will rise as the population ages.1

Economics of Glaucoma

The prevalence of glaucoma contributes to significant costs that are both direct and indirect.13 Direct medical costs include ocular hypotensive medication(s), physician and hospital visits, and glaucoma-related procedures while direct nonmedical costs include transportation, government purchase programs, guide dogs, and nursing home care. Indirect costs reflect lost productivity, such as days missed from work, and can include the productivity costs borne by caregivers such as family members and friends.

Direct cost estimates for the approximately 2 million US citizens13 and 300 000 Australian citizens14 with glaucoma are $2.9 billion and Aus$144.2 million, respectively. However, these figures likely underestimate the true societal costs if all were to be treated since about half of patients with glaucoma are unaware.7-11 A Markov model populated with data based on US Medicare claims data from 1999 to 200515 estimated the incremental costs of a case of POAG from the payor's perspective, including both direct and indirect medical costs. The average lifetime cost of medical treatment in the glaucoma cohort was $1688 greater than in the control cohort without glaucoma over their expected lifetime (mean = 12.3 years). Although the difference between the POAG and control cohorts was not statistically significant, the authors estimated the average annual incremental cost to Medicare attributable to POAG to be approximately $137 per patient per year.

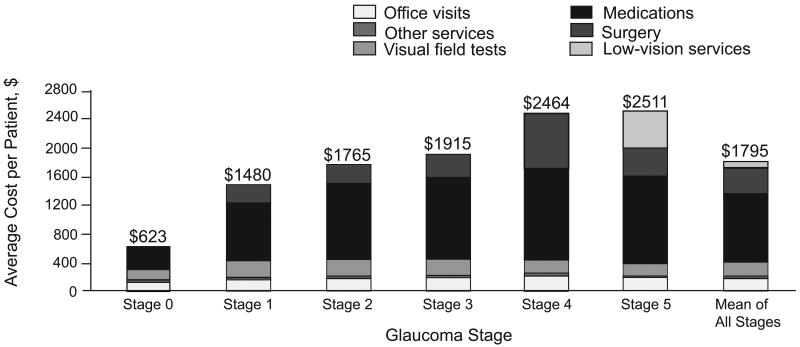

The financial burden of glaucoma increases as disease severity increases (Figure 4). A US study16 found a 4-fold increase in direct ophthalmology-related costs as severity increased from asymptomatic ocular hypertension/earliest glaucoma (stage 0) through advanced glaucoma (stage 3) to end-stage glaucoma/blindness (stage 5): average direct costs per patient per year were $623, $1915, and $2511, respectively. The majority of costs were medication-related at all severity stages. A similar trend was seen in Europe, where direct costs of treatment increased by approximately €86 for each incremental increase in glaucoma stage, ranging from €455 per person year (stage 0) to €969 per person year (stage 4).17 Medication costs ranged from 42% to 56% of direct costs at each disease stage. A retrospective medical chart review in the United States (1990 to 2002; n = 151) and Europe (1995 to 2003; n = 194) found that increased annual costs were associated with higher initial IOP level, higher baseline glaucoma stage, use of ocular hypotensive medication, and glaucoma-related surgery.18

Figure 4.

The financial burden of glaucoma increases with disease severity.16 Total annual direct cost of glaucoma treatment per patient by stage. Reprinted from Arch Ophthalmol; Vol 124; Lee PP, Walt JG, Doyle JJ, et al.; “A multicenter, retrospective pilot study of resource use and costs associated with severity of disease in glaucoma”; pages 12-19. Copyright © 2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

The direct cost burden is observed even in the early stages of glaucoma. In France and Sweden, total annual direct treatment costs per patient in a cohort in whom the majority was in early stages of glaucoma were estimated to be €390 and €531, respectively.19 Medication costs comprised nearly half of total costs in both countries. Individuals with late-stage disease incur significant additional indirect costs and constitute a substantial burden on health care resources.20,21 Late disease leads to greater indirect costs (eg, family/home help and rehabilitation costs) that become the predominant driver of overall costs. Indirect costs are difficult to measure, and studies have used various methods to estimate these costs, including patient/family diaries and interviews. In Europe, the average annual direct health care cost of glaucoma-related blindness has been estimated to be between €429 and €523 per patient while annual total costs, including rehabilitation costs and costs to families, were estimated to be between €11 758 and €19 111.20 In 2005, the annual health care costs of individuals with late-stage glaucoma averaged €830 per patient across France, Denmark, Germany, and the United Kingdom; the largest contributor to total annual maintenance costs was assistance in the home, ranging from €633 in Germany to €4878 in France.21

Efforts have been made to estimate the cost effectiveness to identify and to treat glaucoma and ocular hypertension.22-25 A computer model of 20 million people aged 50 or older in the United States simulated routine ophthalmologic care and resulting glaucoma diagnoses and medical treatment.22 Glaucoma treatment was highly cost-effective when costs associated with diagnostic assessments were excluded and when optimistic assumptions about treatment efficacy were made. Furthermore, costs compared favorably with standards established by the World Health Organization even when efficacy assumptions were conservative. Stewart et al23 developed a Markov model to evaluate the long-term cost effectiveness of treating ocular hypertension in the United States to prevent progression to glaucoma. While treating all patients with ocular hypertension did not prove to be cost effective, treating those with risk factors identified by the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study did seem to prevent the onset of glaucoma cost effectively. Similarly, Kymes et al24 concluded that treating individuals with an IOP ≥24 mm Hg and a ≥2% annual risk of developing glaucoma met cost-effectiveness standards accepted in most developed countries. An Australian team25 estimated that implementing an intervention package, VISION 2020, targeting visual impairment would cost Aus$5591 per quality-adjusted life-year in the first year and would be cost saving in subsequent years.

In summary, the economic burden of glaucoma is significant and increases as the disease worsens. Analysts have used a variety of approaches to quantify the economic burden of glaucoma, making direct comparisons among studies and across populations difficult. Results of a collaborative effort to delineate guidelines for calculating the economic burden of visual impairment recently have been published,26 and it is hoped that future studies will implement its recommendations.

Individual Burden of Glaucoma

Glaucoma impacts patients' health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in multiple ways, including driving, walking, and reading. The psychological burden increases as vision decreases, along with a growing fear of blindness, social withdrawal from impaired vision, and depression. The components of a good HRQoL differ among individuals, but having enough visual ability is a high priority. HRQoL is a concept that reflects a person's well-being and that focuses on dimensions of physical functioning, social functioning, mental health, and general health perceptions.

Measurable loss in HRQoL is observed even in early stage glaucoma.27 While the impact occurs very early even with mild disease in 1 eye, when visual field loss affects both eyes, the impact is far greater (Figure 5). The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study (LALES) included a large number of adults without prior knowledge of their glaucoma status, enabling an assessment of the association between self-reported HRQoL and visual field loss among a population three-quarters of whom had no prior knowledge of glaucoma.28 Including the one-quarter with knowledge, glaucoma cases with severe visual field loss had lower HRQoL scores, an association that persisted after controlling for knowledge of glaucoma or treatment. The negative effects of visual field loss were present in individuals who were previously unaware that they had glaucoma. Even with early vision loss, a significant impact was noted, and with greater severity, the impact of visual field loss on HRQoL is linear. Greater visual field loss in the better-seeing eye was associated with worse HRQoL, a pattern that persisted when both eyes were assessed together (binocular visual field; Figure 6A and B, respectively).

Figure 5.

Visual field loss negatively impacts health-related quality of life.27 Comparison of effect sizes (ES)s between the no visual field loss (VFL) subgroup with subgroups with different severity levels of VFL. The level of VFL was stratified into five categories: no VFL (mean deviation [MD] > _2 decibels [dB] in both eyes), unilateral mild VFL (-6 dB <MD< -2 dB in the worse eye), unilateral moderate to severe VFL (MD<-6 dB in one eye, MD > _2 dB in the other eye), bilateral mild VFL (_6 dB < MD < _2 dB in both eyes; or _6 dB < MD < _2 dB in one eye, MD < _6 dB in the other eye), and bilateral moderate to severe VFL (MD < _6 dB in both eyes). The ES was calculated as the difference in the adjusted mean scores (between each of the severity level of VFL and no VFL) divided by the standard deviation for the no VFL group. Subscales are clustered in decreasing order of ESs for the bilateral moderate to severe VFL vs none groups, for the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ-25) vision-related subscales, and the Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) general health subscale scores. ESs below 0.20 represent no statistically significant effect. An ES of 0.20 to 0.49 is considered to be a small effect, 0.50 to 0.79 a medium effect, and 0.80 or more a large effect.

Reprinted from Am J Ophthalmol; Vol 143; McKean-Cowdin R, Varma R, Wu J, et al.; “Severity of visual field loss and health-related quality of life”; pages1013-1023. Copyright 2007, with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 6.

Visual field loss and health-related quality of life are positively associated.28 A. Better-seeing eye: Locally weighted least squares plot of the relationship of predicted 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ-25) composite scores and the driving subscale score (adjusted for covariates) by visual field loss in the better-seeing eyes of participants with open-angle glaucoma in the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. dB = decibels.

B. Both eyes: Locally weighted least squares plot of the relationship of predicted 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ-25) composite scores (adjusted for covariates) and calculated binocular visual field loss (VFL) (probability summation of data from the two eyes was used to compute a single binocular VFL score) of participants with open-angle glaucoma in the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study.

Reprinted from Ophthalmology; Vol 115; McKean-Cowdin R, Wang Y, et al. “Impact of visual field loss on health-related quality of life in glaucoma: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study”; pages 941-948. Copyright 2008, with permission from Elsevier.

The detrimental impact of vision loss in 1 eye is multiplied when vision loss is bilateral. Patients with glaucoma in both eyes had significantly lower scores on the Activities of Daily Vision Scale than those without glaucoma,29 and patients with bilateral moderate or severe visual impairment reported the poorest visual functioning.30 Even after adjusting for visual acuity, demographic characteristics, and other health factors, individuals with bilateral glaucoma exhibit substantially reduced mobility.31

Daily challenges to those with visual field loss are seen across all stages of glaucoma compared with subjects with normal vision.32 The factors most affected included personal care/household tasks and outdoor mobility. As the condition progresses, individuals are less able to perform everyday activities. Vision loss presents significant physical challenges for glaucoma patients. When compared with a control group with similar systemic medical conditions, those with glaucoma were >3 times more likely to have fallen within the prior 12 months, >6 times more likely to have been involved in at least 1 motor vehicle collision within the previous 5 years, and more likely to have been at fault when involved in a motor vehicle accident (Figure 7).33 Using US Medicare claims data (1999 through 2005), individuals newly diagnosed with POAG were at somewhat higher risk for depression, nursing home admission, and home health service than those in a matched control cohort.15 Although it has been suggested that depression may be more closely associated with difficulty with vision-related tasks than with objectively measured vision,34 a trend of increasing depression with increasing glaucoma severity has been noted.35

Figure 7.

Glaucoma patients face physical challenges.33 Proportion of subjects in the glaucoma group (n= 48) and the normal control group (n=47) who reported one or more falls in the previous 12 months. Proportion of drivers in the glaucoma group (n= 40) and the normal control group (n= 44) who reported one or more motor vehicle collisions (MVCs) in the previous 5 years. Data shown for self-reported MVCs (left) and police-reported MVCs (right), for all involvement (regardless of fault), and at-fault involvement. Province-recorded police reports were obtained for 38 and 44 drivers in the glaucoma and control groups, respectively. Police-reported at-fault MVCs were indeterminate for three of eight glaucoma and three of four control subjects with province recorded involvement. Reprinted with permission from Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci; Vol 48; Haymes SA, Leblanc RP, Nicolela MT, et al. “Risk of falls and motor vehicle collisions in glaucoma”; pages 1149-1155. Copyright 2007.

In summary, vision loss from glaucoma has a significant impact on HRQoL even in the early stages of disease, and this impact extends to undiagnosed as well as diagnosed patients. Ongoing visual field loss can impair patients' abilities to perform common daily activities and also may impose an increasing psychological burden on patients and their families.

Comment

Glaucoma is common, on the rise, underdiagnosed, costly, distressing to those affected and their families, and disabling. As the population increases, so does the absolute number of glaucoma sufferers. In addition, with glaucoma prevalence increasing exponentially with age, glaucoma numbers are rising with the rapidly aging population. Glaucoma patients are estimated to rise in number from 60 million in 2010 to nearly 80 million in 2020, with more than half in developed societies remaining undiagnosed. In developing communities, the proportion undiagnosed is significantly higher. Glaucoma-related visual disabilities should be preventable, and the burden of functional vision loss related to the condition is not fully recognized. Recently published data demonstrate the growing global cost and societal burdens of glaucoma. Both economic and individual costs increase with disease severity; however, proactive glaucoma management may reduce the overall disease burden. Early identification and treatment of patients with glaucoma and those with ocular hypertension at high risk of developing vision loss may reduce the individual burden of disease on HRQoL and also may minimize personal and societal economic burdens. The information provided herein may enhance the awareness of physicians, policymakers, and the public about the burden of glaucoma and help put glaucoma in its appropriate place for prioritization.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The study was supported by Pfizer Inc, New York, New York.

Editorial support, including contributing to the first draft of the manuscript based on presentations prepared by the authors, revising the paper based on author feedback, and styling the paper for journal submission, was provided by Jane G. Murphy, PhD, of Zola Associates and was funded by Pfizer Inc, New York, New York. The authors wish to thank Alpa Khambhati for assistance in reviewing literature published from 1996 through August 2008. The authors have obtained written permission from all persons named in the acknowledgments.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Drs. Varma, Lee, and Goldberg are paid consultants to Pfizer Inc and participated in the study design; data analysis and interpretation; and preparation and review of the manuscript. Mr. Kotak is an employee of Pfizer Inc and participated in the study design; data analysis and interpretation; and preparation and review of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinreb RN, Friedman DS, Fechtner RD, et al. Risk assessment in the management of patients with ocular hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(3):458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman AL, Miglior S. Risk factors for glaucoma onset and progression. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(1 suppl):S3–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman DS, Wilson MR, Liebmann JM, Fechtner RD, Weinreb RN. An evidence-based assessment of risk factors for the progression of ocular hypertension and glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(3 suppl):S19–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman DS, West SK, Muñoz B, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):532–538. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman DS, Jampel HD, Muñoz B, West SK. The prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among blacks and whites 73 years and older: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Glaucoma Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(11):1625–1630. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.11.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varma R, Ying-Lai M, Francis BA, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension in Latinos: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(8):1439–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Voogd S, Ikram MK, Wolfs RC, Jansonius NM, Hofman A, de Jong PT. Incidence of open-angle glaucoma in a general elderly population: the Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(9):1487–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tielsch JM, Sommer A, Katz J, Royall RM, Quigley HA, Javitt J. Racial variations in the prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma. The Baltimore Eye Survey. JAMA. 1991;266(3):369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quigley HA, West SK, Rodriguez J, Munoz B, Klein R, Snyder R. The prevalence of glaucoma in a population-based study of Hispanic subjects: Proyecto VER. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(12):1819–1826. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.12.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell P, Smith W, Attebo K, Healey PR. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma in Australia. The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(1):1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30449-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein JD, Ayyagari P, Sloan FA, Lee PP. Rates of glaucoma medication utilization among persons with primary open-angle glaucoma, 1992 to 2002. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1315–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rein DB, Zhang P, Wirth KE, et al. The economic burden of major adult visual disorders in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(12):1754–1760. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor HR, Pezzullo ML, Keeffe JE. The economic impact and cost of visual impairment in Australia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):272–275. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.080986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kymes SM, Plotzke MR, Li JZ, Nichol MB, Wu J, Fain J. The increased cost of medical services for people diagnosed with primary open angle glaucoma – a decision analytic approach. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee PP, Walt JG, Doyle JJ, et al. A multicenter, retrospective pilot study of resource use and costs associated with severity of disease in glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(1):12–19. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Traverso CE, Walt JG, Kelly SP, et al. Direct costs of glaucoma and severity of the disease: a multinational long term study of resource utilisation in Europe. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(1):1245–1249. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.067355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee PP, Kelly SP, Mills RP, et al. Glaucoma in the United States and Europe: predicting costs and surgical rates based upon stage of disease. J Glaucoma. 2007;16(5):471–478. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3180575202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindblom B, Nordmann JP, Sellem E, et al. A multicentre, retrospective study of resource utilization and costs associated with glaucoma management in France and Sweden. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84(7):74–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poulsen PB, Buchholz P, Walt JG, et al. Cost-analysis of glaucoma-related blindness in Europe. International Congress Series. 2005;1282:262–266. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thygesen J, Aagren M, Arnavielle S, et al. Late-stage, primary open-angle glaucoma in Europe: social and health care maintenance costs and quality of life of patients from 4 countries. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(6):1763–1770. doi: 10.1185/03007990802111068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Lee PP, et al. The cost-effectiveness of routine office-based identification and subsequent medical treatment of primary open-angle glaucoma in the United States. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(5):823–832. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart WC, Stewart JA, Nasser QJ, Mychaskiw MA. Cost-effectiveness of treating ocular hypertension. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kymes SM, Kass MA, Anderson DR, et al. Management of ocular hypertension: a cost-effectiveness approach from the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(6):997–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor HR, Pezzullo ML, Nesbitt SJ, Keeffe JE. Costs of interventions for visual impairment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(4):561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frick KD, Kymes SM, Lee PP, et al. The cost of visual impairment: purpose, perspectives and guidance. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(4):1801–1805. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKean-Cowdin R, Varma R, Wu J, et al. Severity of visual field loss and health-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(6):1013–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKean-Cowdin R, Wang Y, Wu J, et al. Impact of visual field loss on health-related quality of life in glaucoma: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(6):941–948. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freeman EE, Muñoz B, West SK, et al. Glaucoma and quality of life: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2):233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varma R, Wu J, Chong K, et al. Impact of severity and bilaterality of visual impairment on health-related quality of life. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(1):1846–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman DS, Freeman E, Muñoz B, Jampel HD, West SK. Glaucoma and mobility performance: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Project. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(12):2232–2237. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson P, Aspinall P, Papasouliotis O, Worton B, O'Brien C. Quality of life in glaucoma and its relationship with visual function. J Glaucoma. 2003;12(2):139–150. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200304000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haymes SA, Leblanc RP, Nicolela MT, Chiasson LA, Chauhan BC. Risk of falls and motor vehicle collisions in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(3):1149–1155. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jampel HD, Schwartz A, Pollack I, Abrams D, Weiss H, Miller R. Glaucoma patients' assessment of their visual function and quality of life. J Glaucoma. 2002;11(2):154–163. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200204000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skalicky S, Goldberg I. Depression and quality of life in patients with glaucoma: a cross-sectional analysis using the Geriatric Depression Scale-15, assessment of function related to vision, and the Glaucoma Quality of Life-15. J Glaucoma. 2008;17(7):546–551. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318163bdd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]