Abstract

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) plays an essential role in the control of total peripheral vascular resistance by controlling the contraction of small arteries. The SNS also exerts long-term trophic influences in health and disease; SNS hyperactivity accompanies most forms of human essential hypertension, obesity, and heart failure. At their junctions with smooth muscle cells, the peri-arterial sympathetic nerves release ATP, noradrenaline (NA) and neuropeptide Y (NPY) onto smooth muscle cells. Confocal Ca2+ imaging studies reveal that ATP and NA each produce unique types of post-junctional Ca2+ signals, and consequent smooth muscle cell contractions. Neurally released ATP activates post-junctional P2X1 receptors to produce local, non-propagating Ca2+ transients, termed ‘junctional Ca2+ transients’, or jCaTs. Neurally released NA binds to α1-adrenoceptors and can activate Ca2+ waves or more uniform global changes in [Ca2+]. Neurally released NPY does not appear to produce Ca2+ transients directly, but significantly modulates NA-induced Ca2+ signaling. The neural release of ATP and NA, as judged by post-junctional Ca2+ signals, electrical recording of excitatory junction potentials (EJPs), and carbon fiber amperometry to measure NA, varies markedly with the pattern of nerve activity. This probably reflects both pre- and post-junctional mechanisms, which are not yet fully understood. These phenomena, together with different temporal patterns of sympathetic nerve activity in different regional circulations, are probably an important mechanistic basis of the important selective regulation of regional vascular resistance and blood flow by the sympathetic nervous system.

Keywords: sympathetic nerve, Ca2+ Signaling, arterial smooth muscle, receptors, junctional Ca2+ transients (jCaTs), confocal microscope

Introduction

All three sympathetic co-transmitters, ATP, NA, and NPY contribute to sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction of small arteries (Bradley et al., 2003). Abundant evidence supports the concept that, in arteries, neurally released ATP can activate a rapid, transient, component of smooth muscle contraction whilst neurally released NA activates slower, sustained and stronger contraction. These components of contraction are often referred to as the ‘purinergic’ and the ‘adrenergic’ component of neurogenic contraction, respectively. The actions and mechanisms of neurally released NPY remain more obscure; although NPY is a weak vasoconstrictor, it is likely that its primary (post-junctional) role is to modulate the actions of NA, and possibly, ATP.

The actions and relative contributions of each transmitter to sympathetic neuromuscular transmission vary markedly throughout the vascular system, and with the pattern of sympathetic nerve activity. For example, in the mesenteric vascular bed, the purinergic component of the contraction is relatively larger in the very small mesenteric arteries, compared to the larger ones, and the purinergic component predominates during brief bursts of sympathetic nerve fiber activity (Gitterman & Evans, 2001). In these arteries also, the relative importance of ATP as an activator of contraction may depend on arterial pressure (Rummery et al., 2007). Contraction of distal small arteries supplying skeletal muscle however does not seem to involve ATP at all (Tarasova et al., 2003). The varying contributions of the three sympathetic co-transmitters in different conditions and in different arteries is undoubtedly the result of many factors, including; 1) the unique frequency-dependence of release of each transmitter, 2) the identity, location and intracellular mechanisms of pre-and post-junctional receptors for each, and 3) the activity of mechanisms for terminating the actions of each transmitter.

Here, we focus on the Ca2+ signaling that is elicited in arterial smooth muscle cells by neurally released sympathetic neurotransmitters. As we have pointed out recently (Zang et al., 2006) Ca2+ signaling during neurogenic contractions activated by trains of sympathetic nerve fiber action potentials is, in fact, significantly different from that elicited by the simple application of exogenous neurotransmitters (both ATP and NA) to isolated arteries (or single isolated smooth muscle cells). Neurogenic Ca2+ signaling in some other types of smooth muscles, such as vas deferens (Brain et al., 2003) and urinary bladder (Heppner et al., 2005) has also been studied recently.

Results

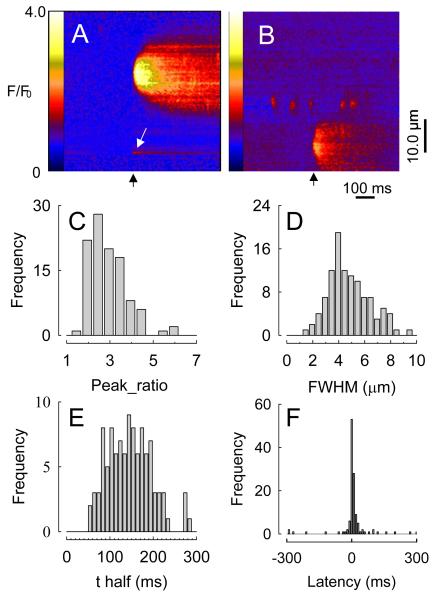

jCaTs: The post-junctional Ca2+ transient elicited by neurally released ATP and P2X1

Initial studies on neurogenic Ca2+ signaling in vascular smooth muscle utilized confocal imaging of Ca2+-activated fluo-4 fluorescence in pressurized (70 mmHg) rat mesenteric small arteries subjected to electrical field stimulation (EFS). To facilitate imaging, low frequency (0.67 Hz), low voltage EFS was used to excite nerve fibers without causing an appreciable contraction. This was referred to as ‘sub-threshold’ EFS, as it was sub-threshold for muscle contraction. Thus, in these experiments, motion did not occur and the characteristics of neurogenic Ca2+ signals could be studied in detail. A novel type of Ca2+ transient, arising near nerve fibers, was observed (Fig. 1). These were called ‘junctional Ca2+ transients’ or ‘jCaTs’, as they appeared to represent the post-junctional response to release of sympathetic neurotransmitter. Nerve fiber Ca2+ transients were also observed. The results showed that 1) nerve fibers are excited by each EFS pulse; 2) jCaTs occur nearly simultaneously with an EFS pulse, 3) jCaTs occur near nerve fibers, and 4) jCaTs are events of very low probability. JCaTs are larger in spatial spread and last longer than spontaneous Ca2+ sparks (Jaggar et al., 2000). JCaTs always occurred with brief latency to the EFS pulse. The spatial full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) for jCaTs was 4.8μm, and the time taken to fall to half-amplitude, t1/2, (from the peak) is 145ms. Unequivocal identification of the receptor(s) and ion channels that underlie jCaTs has been accomplished recently through the use of the P2X1–receptor deficient mouse (Lamont et al., 2006). In the arteries of these animals, the P2X receptor agonist, α, β-methylene ATP elicited no response, and jCaTs were completely absent during nerve stimulation, confirming the absolute requirement for P2X1 receptors in the post-junctional responses to ATP.

Figure 1. Junctional Ca2+ transients in line-scan images, expressed as fluorescence pseudo-ratios (F/F0).

A, Black arrow indicates time of stimulus pulse. White arrow indicates (unrelated) nerve fiber Ca2+ transient. B, jCaT with spontaneous Ca2+ sparks. C through E, Probability density histograms of peak F/F0, FWHM, and t1/2 for all jCaTs (F). Probability density histogram of latencies of all jCaTs, showing a few spontaneous jCaTs (Lamont & Wier, 2002).

Neurogenic Ca2+ Signals in Contracting Arteries

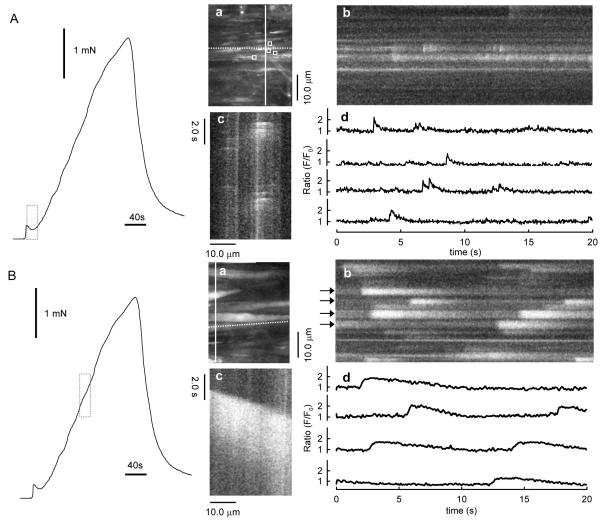

As mentioned, some of the studies described above were obtained in pressurized small arteries that did not contract because the electrical stimulation was ‘sub-threshold’ for contraction. However, neurogenic Ca2+ signals have also been observed during isometric neurogenic contractions. For these studies, segments of arteries were mounted on a confocal myograph (Danish Myo Technology A/S Aarhus, Denmark) between two 40μm wires, one of which was fixed the other of which was attached to a force transducer and peri-vascular nerve fibers were stimulated with EFS. Studies utilizing a myograph permitted simultaneous i) high-speed confocal imaging of fluorescence from individual smooth muscle cells, ii) electrical stimulation of perivascular nerves, and iii) recording of isometric tension. As shown in Fig. 2, during the first 20s of EFS, force rose to a small peak, then declined, similar to that recorded previously (Nilsson et al., 1986). During this time, jCaTs were present at relatively high frequency. Propagating asynchronous Ca2+ waves, previously associated with bath-applied α1-adrenoceptor agonists (Zang et al., 2001), were not initially present. During the next 2.5 minutes of EFS, force rose slowly, and asynchronous propagating Ca2+ waves appeared. The selective α1-adrenoceptor antagonist, prazosin, abolished both the slowly developing contraction and the Ca2+ waves, but reduced the initial transient contraction by only ~25%. These results suggested that neurogenic contractions under these conditions consisted of an early, transient purinergic component (the jCaTs) and a later developing adrenergic component.

Figure 2. Occurrence of jCaTs during the predominantly purinergic component (A) and Ca2+ waves during the predominantly adrenergic component (B) of neurogenic contraction.

Records at left of both (A) and (B) are the force produced by EFS for 3 minutes. The dotted vertical bars indicate the times during which images in (a)–(c) and traces in (d) were obtained. (Aa and Ba) Image obtained by averaging 30 frames (1s) during the period indicated. Ab and Bb are virtual line-scan images derived from a selected single vertical line of pixels in images Aa and Bb, respectively (solid white line). Ac and Bc are virtual line-scan images derived from a single horizontal line of pixels in images Aa and Ba, respectively (dotted white line). Traces in (Ad) are fluorescence pseudo-ratios (F/F0) derived from the average fluorescence within selected areas-of-interest (AOIs) in the images in Aa (white boxes). Traces in (Bd) are derived from the line-scan image in Bb, at the lines indicated by the black arrows. All the data illustrated here were obtained at 30 images s−1 (Lamont et al., 2003).

Purinergic component

In order to study selectively the Ca2+ signals and contractions generated by neurally released ATP, arteries were exposed to prazosin (1-10μM) to block α1-adrenergic receptors (Lamont et al., 2003). Others (Gitterman & Evans, 2001) have shown that purinergic receptor antagonists, such as suramin, abolish the small contractions that remain after prazosin. After prazosin treatment 73.7±14.0% (n=7) of the initial transient contraction remained and 5.00± 0.98% of the maintained contraction (Lamont et al., 2003). The changes in frequency and amplitude of jCaTs that might occur during the EFS were also characterized. Confocal imaging of fluo-4 fluorescence at 30 images s−1 was performed for 3 periods of 20s in the beginning (0 to 20s), middle (80 to 100s), and end (160 to 180s) of 3 minutes of EFS (Lamont et al., 2003). In arteries exposed to prazosin and stimulated with EFS, the frequency of jCaTs declined markedly during the 3 minutes of EFS. In contrast to the frequency, the peak amplitude of the jCaTs changed little during 3 minutes of EFS. Propagating Ca2+ waves were not observed during EFS in the presence of prazosin. JCaTs occurred in sufficient numbers during the first 20s of EFS to produce a detectable elevation of average [Ca2+] (fluorescence ratio), which paralleled the transient contraction that occurred during this time. On the other hand, jCaTs occurred at a very low frequency later in the EFS, when contractile force fell to very low levels (Lamont et al., 2003). Thus, it seems reasonable to attribute the contractile activation to jCaTs, despite their limited spatial extent and frequency.

Adrenergic component

During the subsequent neurogenic contractions (Fig. 2B), asynchronous Ca2+ waves propagated within individual smooth muscle cells of the arterial wall. Ca2+ signal was obtained as the average fluorescence within a single smooth muscle cell. Images were obtained at 2s−1, a rate, which is too slow to resolve the jCaTs generated during the initial purinergic component (Lamont & Wier, 2002). In this study 809 Ca2+ waves were detected in 74 cells, and the time of onset and peak amplitude of each was determined.

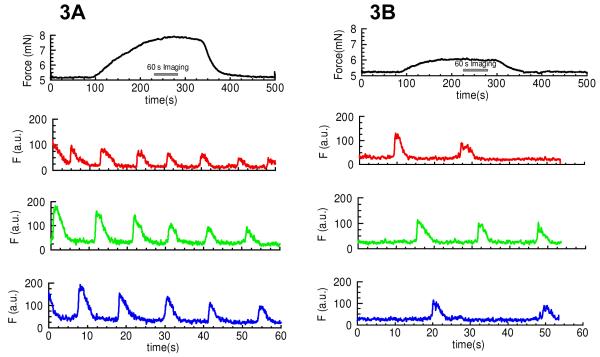

NPY’s effect on the adrenergic component of neurogenic contraction

Adrenergic contractions were induced with PE (2μM) in the absence and presence of 10nM NPY (Fig. 3). Calcium signals within the arterial smooth muscle cells were also observed using confocal wire myography. 10nM NPY increased the frequency of asynchronous calcium waves induced by 2μM PE from 1.38±0.28 to 3.95±0.54 waves/cell/min (120 cells, 3 arteries) and increased the PE-induced force by up to 3-fold (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Mechanism of NPY’s effect on the adrenergic component of sympathetic neurogenic contraction.

Adrenergic contractions were induced with PE (2μM) in the absence (Fig. 3A) and presence (Fig. 3B) of 10nM NPY. The top most trace shows force, the bottom traces are calcium signals within three different arterial smooth muscle cells using confocal wire myography. 10nM NPY increases the frequency of asynchronous calcium waves induced by 2μM PE from 1.38±0.28 to 3.95±0.54 waves/cell/min (120 cells, 3 arteries) and increased the force 3-fold, n=3.

Discussion

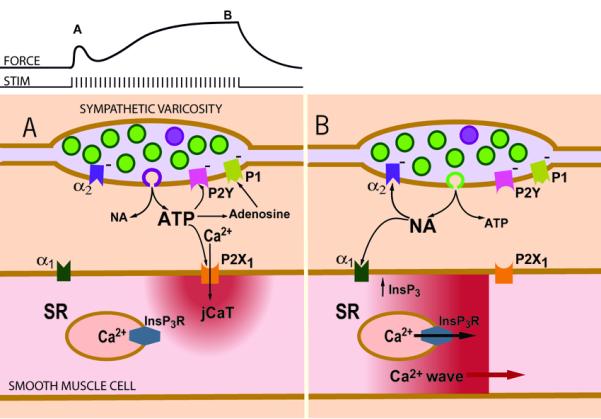

We have previously advanced a scheme to explain the Ca2+ signals and isometric contraction elicited by electrical field stimulation of perivascular sympathetic nerves of a rat mesenteric small artery (Fig. 4). Early during a train of nerve fiber action potentials, smooth muscle contraction is activated mainly by jCaTs induced by neurally released ATP. JCaTs are localized to the post-junctional region, and arise from Ca2+ that has entered via P2X receptors. At this time, sympathetic varicosities may release mainly small vesicles that contain a relatively high concentration of ATP (viz. the relatively few ‘big’ quanta proposed by Stjarne (Stjarne, 2001). Later during a train of nerve fiber action potentials, jCaTs are rare, and contraction is activated by Ca2+ waves that arise from sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Ca2+ release from SR is activated by InsP3, produced after binding of NA to α1-adrenoceptors. At this time, sympathetic varicosities may release small synaptic vesicles that contain a relatively high concentration of NA.

Figure 4. Scheme of Ca2+ signaling induced by sympathetic neuromuscular transmission in a small artery.

(A) Early during a train of nerve fiber action potentials, smooth muscle contraction is activated mainly by post-junctional Ca2+ transients (jCaTs) induced by neurally released ATP. JCaTs are localized to the post-junctional region, and arise from Ca2+ that has entered via P2X receptors. At this time, sympathetic varicosities may release mainly small vesicles that contain a relatively high concentration of ATP (viz. the relatively few ‘big’ quanta proposed by Stjarne, 2001) (B) Later during a train of nerve fibre action potentials, jCaTs are rare, and contraction is activated by Ca2+ waves that arise from sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Ca2+ release from SR is activated by InsP3, produced after binding of NA to α1-adrenoceptors. At this time, sympathetic varicosities may release small synaptic vesicles (the more numerous ‘small’ quanta, green) that contain a relatively high concentration of NA. An effect not shown in the scheme is the action of neurally released NPY to increase the frequency of NA induced Ca2+ waves. Figure reproduced from (Wier, 2003)).

JCaTs are distinct from Ca2+ transients activated in isolated venous myocytes by exogenously applied ATP (Mironneau et al., 2001). Previous studies of the effects of ATP on small arteries utilized spatially averaged measurements of Ca2+ (Lagaud et al., 1996; Mironneau et al., 2001) and we cannot determine therefore whether jCaTs might be produced by bath-applied ATP or not. In rat mesenteric small arteries similar to those used here, low concentrations of exogenous ATP (viz. 0.01-1mM) caused ‘global’ Ca2+ transients that seemed to involve Ca2+ influx through channels sensitive to nifedipine and the putative blocker of receptor operated channels, SKF 96365 (Putney et al., 2001), whereas higher concentrations of ATP (1-3mM) caused a release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores (Ca2+ transients were elicited by high [ATP] in the absence of external Ca2+). When applied to isolated venous myocytes, low concentrations of ATP (0.1μM) induced ‘rather uniform’ increases in Ca2+ (which started from the edges of the cell), and at higher concentrations (1μM), propagating Ca2+ waves (Mironneau et al., 2001).

In the arteries studied in the presence of prazosin, no propagating Ca2+ waves were ever observed during EFS. This can be interpreted as neurally released ATP not evoking significant release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores, a result in agreement with previous pharmacological studies on rat mesenteric small arteries (Gitterman & Evans, 2001). It can be thus speculated that the differences between the effects of bath-applied ATP and neurally-released ATP are due to a markedly different spatio-temporal pattern of [ATP] on the smooth muscle cell in the two cases.

Both the contraction and the underlying Ca2+ signals during the adrenergic component of the neurogenic isometric contraction are also distinctly different from those occurring during externally applied α1-adrenoceptor agonist (typically phenylephrine). After the initial purinergic component, the adrenergic component of the neurogenic contractions, even at maximally effective EFS, rises much more slowly than does the contraction in response to bath-applied α1-adrenoceptor agonist. Maximally effective concentrations of exogenous PE elicit an initial synchronous release of Ca2+, followed by asynchronous propagating Ca2+ waves, both in veins (Ruehlmann et al., 2000) and in arteries (Mauban et al., 2001; Zang et al., 2001). Thus, the initial rapid rise in force in response to externally applied PE appears to be generated by a synchronous release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. This does not occur during neurogenic contractions, possibly because neuronally released NA does not initially reach the uniformly high levels that are achieved rapidly after external application.

It has been suggested previously (Prieto et al., 1997) that NPY activates mesenteric small arteries through two different mechanisms; 1) activation of non-selective cation channels, with consequent Ca2+ entry, and 2) inhibition of cAMP-mediated hyperpolarization (consequent to a decrease in [cAMP]). The latter is consistent with the fact that some types of NPY receptors are coupled to pertussistoxin-sensitive G proteins and are able to mediate decreases in [cAMP]. Consistenst with this, neuronally released NPY potently inhibits the ability of forskolin to relax agonist induced contraction of rat mesenteric arteries (Prieto et al., 2000), an effect likely due to stimulation of Gi with subsequent inhibition of Adenylyl cyclase (AC) and decrease in [cAMP]. A cAMP mediated mechanism to explain the present results (increasing the frequency of NA-induced Ca2+ waves) seems unlikely. Such a mechanism would require that basal levels of cAMP (presumably already low) be significantly reduced by NPY and, further, that this decrease of cAMP would have a significant effect on membrane potential. To explain the action of NPY to increase the frequency of NA induced Ca2+ waves in arteries, the mechanism described recently for cardiac cells may be more relevant. In those cells, NPY, acting on Y1 receptors, has a positive inotropic effect that is not pertussis-toxin sensitive but that involves stimulation of phospholipase C (PLC) and increased Ca2+ release (Heredia Mdel et al., 2005). Such an effect would be expected to increase the frequency of Ca2+ waves.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants HL073994 and HL078870. This work was also supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) (No. 2007CB512005), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30770785), the Cultivation Fund of the Key Scientific and Technical Innovation Project of Chinese Ministry of Education (No. 705045) for WJZ.

References

- Bradley E, Law A, Bell D, Johnson CD. Effects of varying impulse number on cotransmitter contributions to sympathetic vasoconstriction in rat tail artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H2007–2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01061.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brain KL, Cuprian AM, Williams DJ, Cunnane TC. The sources and sequestration of Ca(2+) contributing to neuroeffector Ca(2+) transients in the mouse vas deferens. J Physiol. 2003;553:627–635. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitterman DP, Evans RJ. Nerve evoked P2X receptor contractions of rat mesenteric arteries; dependence on vessel size and lack of role of L-type calcium channels and calcium induced calcium release. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:1201–1208. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner TJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Elementary purinergic Ca2+ transients evoked by nerve stimulation in rat urinary bladder smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2005;564:201–212. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mdel P Heredia, Delgado C, Pereira L, Perrier R, Richard S, Vassort G, Benitah JP, Gomez AM. Neuropeptide Y rapidly enhances [Ca2+]i transients and Ca2+ sparks in adult rat ventricular myocytes through Y1 receptor and PLC activation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar JH, Porter VA, Lederer WJ, Nelson MT. Calcium sparks in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C235–256. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.2.C235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagaud GJ, Stoclet JC, Andriantsitohaina R. Calcium handling and purinoceptor subtypes involved in ATP-induced contraction in rat small mesenteric arteries. J Physiol. 1996;492(Pt 3):689–703. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont C, Vainorius E, Wier WG. Purinergic and adrenergic Ca2+ transients during neurogenic contractions of rat mesenteric small arteries. J Physiol. 2003;549:801–808. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.043380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont C, Vial C, Evans RJ, Wier WG. P2X1 receptors mediate sympathetic postjunctional Ca2+ transients in mesenteric small arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H3106–3113. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00466.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont C, Wier WG. Evoked and spontaneous purinergic junctional Ca2+ transients (jCaTs) in rat small arteries. Circ Res. 2002;91:454–456. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000035060.98415.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauban JR, Lamont C, Balke CW, Wier WG. Adrenergic stimulation of rat resistance arteries affects Ca(2+) sparks, Ca(2+) waves, and Ca(2+) oscillations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2399–2405. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironneau J, Coussin F, Morel JL, Barbot C, Jeyakumar LH, Fleischer S, Mironneau C. Calcium signalling through nucleotide receptor P2X1 in rat portal vein myocytes. J Physiol. 2001;536:339–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0339c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson H, Goldstein M, Nilsson O. Adrenergic innervation and neurogenic response in large and small arteries and veins from the rat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1986;126:121–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1986.tb07795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto D, Buus C, Mulvany MJ, Nilsson H. Interactions between neuropeptide Y and the adenylate cyclase pathway in rat mesenteric small arteries: role of membrane potential. J Physiol. 1997;502(Pt 2):281–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.281bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto D, Buus CL, Mulvany MJ, Nilsson H. Neuropeptide Y regulates intracellular calcium through different signalling pathways linked to a Y(1)-receptor in rat mesenteric small arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:1689–1699. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JW, Jr., Broad LM, Braun FJ, Lievremont JP, Bird GS. Mechanisms of capacitative calcium entry. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2223–2229. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.12.2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruehlmann DO, Lee CH, Poburko D, van Breemen C. Asynchronous Ca(2+) waves in intact venous smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2000;86:E72–79. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.4.e72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rummery NM, Brock JA, Pakdeechote P, Ralevic V, Dunn WR. ATP is the predominant sympathetic neurotransmitter in rat mesenteric arteries at high pressure. J Physiol. 2007;582:745–754. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.134825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stjarne L. Novel dual ‘small’ vesicle model of ATP- and noradrenaline-mediated sympathetic neuromuscular transmission. Auton Neurosci. 2001;87:16–36. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasova O, Sjoblom-Widfeldt N, Nilsson H. Transmitter characteristics of cutaneous, renal and skeletal muscle small arteries in the rat. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;177:157–166. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wier WG. A new window on sympathetic neuromuscular transmission. Physiology News. 2003;53:16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zang WJ, Balke CW, Wier WG. Graded alpha1-adrenoceptor activation of arteries involves recruitment of smooth muscle cells to produce ‘all or none’ Ca(2+) signals. Cell Calcium. 2001;29:327–334. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang WJ, Zacharia J, Lamont C, Wier WG. Sympathetically evoked Ca2+ signaling in arterial smooth muscle. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:1515–1525. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]