Abstract

Objective

We sought to determine the effect of daily soy supplementation on abdominal fat, glucose metabolism, and circulating inflammatory markers and adipokines in obese, postmenopausal Caucasian and African American women.

Study Design

In a double-blinded controlled trial, 39 postmenopausal women were randomized to soy supplementation or to a casein placebo without isoflavones. Thirty-three completed the study and were analyzed. At baseline and at 3 months, glucose disposal and insulin secretion were measured using hyperglycemic clamps, body composition and body fat distribution were measured by CT scan and DXA, and serum levels of CRP, IL-6, TNF-α, leptin, and adiponectin were measured by immunoassay.

Results

Soy supplementation reduced total and subcutaneous abdominal fat, and IL-6. No difference between groups was noted for glucose metabolism, CRP, TNF-α, leptin, or adiponectin.

Conclusion(s)

Soy supplementation reduced abdominal fat in obese postmenopausal women. Caucasians primarily lost subcutaneous and total abdominal fat, and African Americans primarily lost total body fat.

Keywords: Menopause, obesity, soy, isoflavones, body composition, body fat distribution, race, insulin secretion, glucose metabolism

Cardiovascular disease increases with advancing age and with the menopause transition in women.1–4 Specifically, menopause is associated with changes in several metabolic cardiovascular risk factors, including increased abdominal fat,5 decreased insulin sensitivity, decreased adiponectin,6 and increased circulating inflammatory markers such as TNF-α.7 Traditionally, these risk factors, along with a worsening lipid profile, can be modified by weight loss and exercise to reduce cardiovascular disease risk.

Information is limited regarding the effect of alternative therapy such as soy supplementation on the modification of metabolic cardiovascular risk factors. Animal studies suggest a beneficial effect, with soy supplementation decreasing visceral fat and increasing insulin sensitivity in male rats,8 and decreasing weight, visceral fat, and plasma leptin in female rats.9 In male monkeys, soy protein alone reduced body weight, and soy protein with isoflavones increased insulin secretion.10 Beneficial effects of soy supplementation might be due to the isoflavone binding to estrogen receptors in fat depots, or to increases in peroxisome proliferator-activator receptors in muscle with soy protein that are important for insulin action.10

In humans, our group previously reported a beneficial effect of a daily supplement of soy supplementation, with a reduced gain in total abdominal and subcutaneous abdominal fat compared with a daily casein placebo in Caucasian menopausal women.11 Information is mixed with regard to the effect of soy isoflavones on glucose and insulin metabolism in menopausal women, with our group previously reporting no change in insulin secretion with the soy isoflavone supplement, and others reporting that genistein without soy protein reduced fasting glucose and insulin in menopausal women.12

Little information is available with regard to the effect of soy supplementation on circulating inflammatory markers and adipokines in menopausal women,13, 14 and we are not aware of any studies that consider the effect of soy supplementation on body composition in populations of African Americans. In this study, we hypothesized that a daily soy supplement would reduce abdominal fat and improve measures of glucose and insulin metabolism compared to a casein placebo in a population of obese, non-diabetic Caucasian and African American menopausal women. Furthermore, we sought to determine if changes in fat or glucose metabolism were related to changes in cytokines or adipokines with soy isoflavone supplementation in this population.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Thirty-nine postmenopausal women from the Birmingham, AL region were recruited through study advertisements, enrolled, and randomly assigned by the hospital research pharmacy, using a block design of 6, to consume a daily shake supplement containing either soy protein plus isoflavones or an isocaloric casein placebo containing no isoflavones (supplements and placebo donated by Revival Soy, Kernersville, NC). Inclusion for our study mandated that female subjects must be between the ages of 45–60 years, amenorrheic for at least 12 months, have a documented FSH > 30 mIU/ml, and have a body mass index (BMI) between 30–40 kg/m2.

Volunteers were excluded from our study if they were shown to have diabetes mellitus based on a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test; consumed a strict vegetarian or low fat diet, consumed a diet high in fiber or soy based on a standard dietary screening questionnaire, or if there was a weight change of more than ten pounds within the prior 12 months. Other exclusion criteria were the regular consumption of vitamin and mineral supplementation greater than the recommended daily allowance, regular participation in an exercise program (more than twice weekly), cigarette smoking, hormone replacement or selective estrogen receptor modulator therapy within the prior 12 months, known casein/milk allergy, moderate to excessive alcohol consumption (> 2 drinks daily), or a known estrogen-dependent neoplasia.

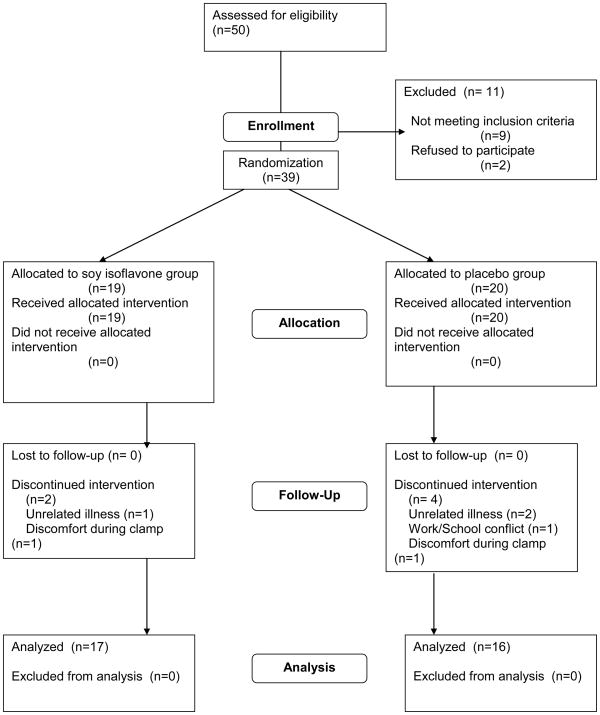

A total of fifty volunteers were assessed for eligibility in the General Clinical Research Center after telephone screening, and thirty-nine met all eligibility criteria. Those that did not meet criteria had diabetes mellitus diagnosed by the 2 hour oral glucose tolerance test (three), had an FSH level too low (four), had clotting irregularities (two), or refused to proceed with the study when presented with more complete information (two). Thirty-nine women were randomized, and thirty-three completed the entire three month study and were analyzed. Of the six drop-outs, three dropped out as a result of unrelated illness, two dropped out because of discomfort during the initial overnight hospitalization, and one dropped out due to a work/school schedule conflict.

Shake Supplements

The composition of the shakes was as follows: 120 calories, 2.5 g fat, 7 g carbohydrates, 600 mg calcium, 500 mg phosphorus, 320 mg sodium, 560 mg potassium, and 3 mg iron. The soy-containing shakes had 20 g soy protein plus 160 mg isoflavones (96 mg available as aglycones). The isocaloric placebo contained 20 g casein protein and no isoflavones. This supplement is well studied and has been used in other trials15. Volunteers mixed the powdered shakes with water in the morning and consumed half of the shake in the morning with breakfast and the other half in the evening with dinner. All were in regular contact with the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) dietician, both prior to enrollment in the study, and throughout the study’s course. Subjects’ weights were checked two weeks post-enrollment, at one month, and at two months. If the weight differed by more than 2.3 kg from the original weight, the dietician was consulted to instruct the volunteer further on weight maintenance. Compliance with the supplements was established by measuring serum isoflavone levels at baseline, four weeks, eight weeks, and twelve weeks. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the GCRC at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and all subjects gave their consent to participate.

Insulin Secretion and Insulin-Stimulated Glucose Disposal

Three days prior to testing, volunteers were given a standardized diet to follow in which meals contained 55% carbohydrates, 30% fat, and 15% protein. After three days, volunteers presented to the GCRC for an overnight admission. On the subsequent morning, following a 12 hour fast, we performed a hyperglycemic clamp as previously described by DeFronzo et al.16 Briefly, a large bore IV catheter was started in an antecubital vein in order to gain access for an infusion of 20% dextrose. A second intravenous catheter used for drawing arterialized blood samples was placed in the contralateral hand, and was kept in a 60°C hot box. When possible, this catheter was placed in a retrograde manner.

Beginning at 7:00 AM a primed, constant infusion of [6,6-2H2]glucose (prime 16.5 μmol/kg, infusion 18.3 μmol/kg/h) was started (time 0 minutes). Blood was sampled at time points 90, 100, 110, and 120 minutes in order to measure glucose concentrations and enrichment. A priming dose of 20% dextrose was then started at time point 120 minutes (240 mg/kg; 15 minutes duration) followed by a variable rate infusion. First-phase insulin secretion was determined by drawing blood samples every two minutes beginning at time point 120 minutes, and continuing through 136 minutes; blood plasma levels of insulin, C-peptide, and plasma glucose were measured. Blood samples were then drawn every five minutes from time point 140 to 240 minutes and glucose levels were determined. Second-phase insulin secretion was determined through plasma levels of C-peptide and insulin levels measured at 15 minute intervals beginning at 140 minutes through 240 minutes.

Tissue glucose uptake (M) was estimated by averaging the glucose infusion rate from 210 to 240 minutes. Insulin sensitivity (M/I) was estimated by dividing the average glucose infusion rate by the average insulin level over the same time period. The rate of appearance of glucose was calculated as described previously.17 This is an index of endogenous glucose production. Total insulin-stimulated glucose disposal is estimated by determining the mean dextrose infusion used to maintain hyperglycemia during the last 30 minutes of the clamp, and the residual endogenous glucose production. Peripheral glucose disposal and endogenous glucose production were summed to determine total glucose disposal.

As described previously, insulin secretion rates were determined using plasma C-peptide levels with deconvolution analysis and linear regularization with use of a two-compartment model using standard parameters for C-peptide kinetics.18,19C-peptide kinetics were assumed to be biexponential, and the exponential parameters were taken to be equal to the mean values, as validated previously.19

Inflammatory markers

Inflammatory markers and adipokines were measured using a multiplexing xMAP technology with a Luminex 100 Analyzer (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX), an immunoassay combining the principle of a sandwich ELISA with fluorescent beads precoated with analyte-specific antibodies. The subsequent color signals were processed and quantified for each analyte.

Body Composition and Body Fat Distribution

Determination of regional and total fat mass, percent fat, and fat-free mass was achieved using dual photon x-ray absorptiometry. A Lunar DPX-L densitometer (Lunar Corp., Madison, WI) was used for scanning, and these scans were analyzed by using the Lunar version 1.3 DPX-L extended analysis program for body composition.

Computed tomographic (CT) scans were used to measure subcutaneous abdominal fat, visceral fat, and total abdominal fat, as we have previously described,17 and as initially described by Sjöström et al.20 Scans were taken at the L4/L5 vertebral disk space at an attenuation range of −190 to −30 Hounsfield units, and analyzed offline using NIHimage software. Subcutaneous abdominal fat was calculated by subtracting visceral abdominal fat from total abdominal fat.

Biochemical Analysis

During the clamp, plasma glucose levels were analyzed with an automated analyzer using the glucose oxidase method (YSI Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH). Serum glucose and C-peptide concentrations were determined using a Tosoh AIA-600 II analyzer (South San Francisco, CA), which employs an immunoenzymatic method utilizing fluorescence. Serum lipid levels (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and triglycerides) were measured at baseline and at 3 months using an automated system for direct measurements based on the change in absorbance at 520 nm (Synchron DxC 800, Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA). Within and between run coefficients of variation for all assays were <4%.

Serum Isoflavones

Determination of serum isoflavones is described previously.11 Briefly, serum levels of genistein, daidzein, glycitein, dihydrodaidzein, O-desmethylangiolensin, and equol were measured by liquid chromatography-multiple reaction ion monitoring-mass spectrometry. All sera samples were run independently in duplicate, and the areas of the isoflavone peaks were normalized by ratio using internal standards, and were compared to normalized areas for isoflavone standards. Intra assay coefficients of variation were 3–10% at the concentrations observed in this study.

Physical Activity

The Minnesota Leisure Time Activity Questionnaire was used to self-report physical activity at the beginning and at the end of the study21. This validated questionnaire was used to determine whether activity levels between groups changed over the course of the 3-month study.

Food Intake

A 4-day food record was collected for each subject at the beginning and at the end of the study and analyzed by registered dieticians from the GCRC. To reflect free- living food intake during the study, dietary intake data were collected using Nutrition Data System for Research software versions 2006 and 2007, developed by the Nutrition Coordinating Center (NCC), University of Minnestota, Minneapolis, MN. Final calculations were completed using version 2007. The NDSR time-related database updates analytic data while maintaining nutrient profiles true to the version used for data collection22.

Statistical Analysis

Primary outcome variables were changes in visceral, subcutaneous, and total abdominal fat by CT scan. Statistical analysis included the calculation of means with standard deviations and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for baseline, and for the differences between the 3 month and baseline time periods. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to test for associations where appropriate. Proportional data were compared by the use of χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. To test for differences by race, we included a race-treatment interaction term in the linear regression model for each outcome variable. Effect size by race was reported only for those where the interaction term was significant. Data were analyzed with SAS, version 9.1 (SAS institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 and all tests were two sided.

Results

Thirty-nine volunteers meeting eligibility criteria were randomized to either soy or placebo arms, and thirty-three completed follow up and were analyzed by intention to treat: 16 randomized to placebo (eight African American, eight Caucasian) and 17 randomized to soy (eight African American, nine Caucasian) (Figure 1). All values presented are means ± S.D. or medians with IQR. Table 1 demonstrates that there was no difference between groups with regard to any baseline demographic variable. A comparison of primary and secondary outcome variables between groups at baseline is shown in Table 2. No differences in outcome variables at baseline were noted.

Figure 1.

Randomization scheme for trial participants.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristics | Placebo (n=16) | Soy (n=17) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 53.3±4.9 | 54.4±3.3 | 0.4519 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.9±5.4 | 35.3±6.0 | 0.2235 |

| Weight (kg) | 90.9±15.6 | 95.6±17.6 | 0.4259 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 94.4±14.1 | 96.4±7.2 | 0.6111 |

| Fasting insulin (μU/mL) | 13.4±10.5 | 12.7±4.1 | 0.8017 |

| Race | |||

| African-American | 50.0 | 47.1 | 0.8658 |

| Caucasian | 50.0 | 52.9 | |

| Married | 50.0 | 52.9 | 0.8658 |

| College education | 100 | 76.5 | 0.1026 |

Data are presented as means ± S.D.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Variable | Placebo (n=16) | Soy (n=17) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral glucose disposal (mg/min) | 447.3±129.7 | 431.4±135.9 | 0.7327 |

| Visceral fat (cm2) | 152.1±70.5 | 172.6±47.7 | 0.3317 |

| Subcutaneous abdominal fat (cm2) | 435.0±143.3 | 513.2±160.7 | 0.1512 |

| Total abdominal fat (cm2) | 587.1±191.2 | 685.9±189.3 | 0.1463 |

| Total body fat (kg) | 43.9±11.5 | 46.6±11.1 | 0.4948 |

| Lean mass (kg) | 43.6±6.0 | 45.1±7.0 | 0.5168 |

| Weight by DXA (kg) | 90.1±15.7 | 94.3±17.5 | 0.4807 |

| First Phase Insulin Secretion AUC (pmol/min) | 5887 (3934–775) | 7720 (5974–9712) | 0.1188 |

| Second Phase Insulin Secretion AUC (pmol/min) | 88581 (67966–105000) | 113000 (87041–124000) | 0.0584 |

| Endogenous glucose production (mg/min) | 285.4(236.9–371.2) | 297.3 (236–370.5) | 0.9857 |

| Leptin (pg/ml) | 37168 (25753–70297) | 44815 (29551–49924) | 0.7334 |

| Adiponectin (ng/ml) | 30740 (19425–41342) | 24588 (14943–29321) | 0.2649 |

| Equol (nM) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0.3975 |

| Daidzein (nM) | 10.1 (2.7–24.6) | 7.8 (0–16.3) | 0.1873 |

| Genistein (nM) | 27.5 (21.8–40.5) | 35.3 (27.4–54.4) | 0.1805 |

| Glycitein (nM) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 1.0 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 1.7 (0.6–4.5) | 2.8 (0.9–5.8) | 0.4814 |

| CRP (ng/ml) | 11664 (3728–45319) | 34148 (19510–44728) | 0.0728 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 1.9 (1.1–2.3) | 1.7 (1.3–2.6) | 0.5926 |

Data are presented as means ± S.D or medians (IQR).

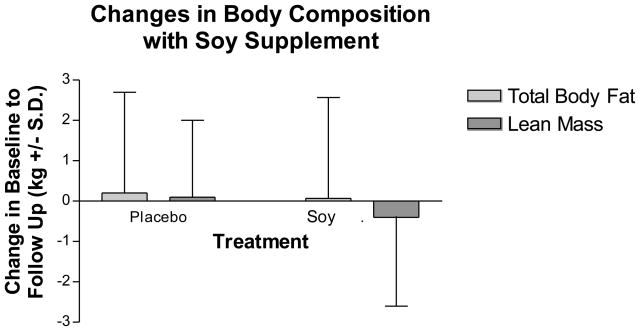

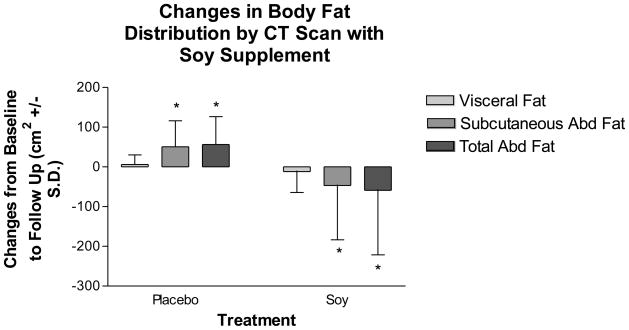

Changes in body composition and body fat distribution during the 3-month study are shown in Figure 2. Total body fat, lean body mass, and weight as measured by DXA did not change in the soy supplement group compared to placebo (Figure 2a). However, soy supplementation improved body fat distribution (Figure 2b). Soy supplementation significantly reduced total abdominal fat by 7.5% (−58.8 ± 162.6 cm2) and subcutaneous abdominal fat by 9.1% (−46.9 ± 136.7 cm2), compared to an increase by casein placebo of 8.8% (56.5 ± 70.0 cm2) in total abdominal fat and 10% (50.8 ± 65.2 cm2) in subcutaneous abdominal fat (differences between groups: p=0.0088 for subcutaneous abdominal fat and 0.0167 for total abdominal fat). There were no significant changes in visceral fat with soy supplementation compared to placebo in the group as a whole, although visceral fat decreased by 2.8% in the soy group and increased by 5.3% in the placebo group (differences between groups: p=0.5591).

Figure 2.

Changes in body composition (2a) and body fat distribution (2b) with the soy supplement and placebo as measured by DXA during the study. Values are means ± S.D. There were no significant differences between groups in changes in body composition. Subcutaneous and total abdominal fat decreased significantly with the soy supplement compared to an increase with placebo.

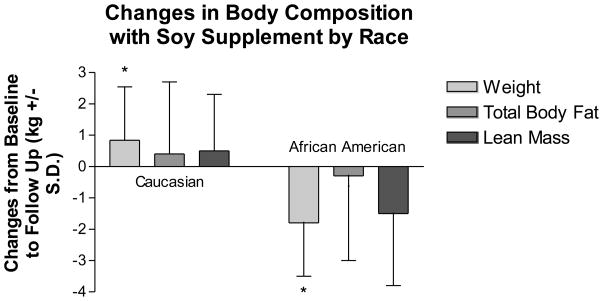

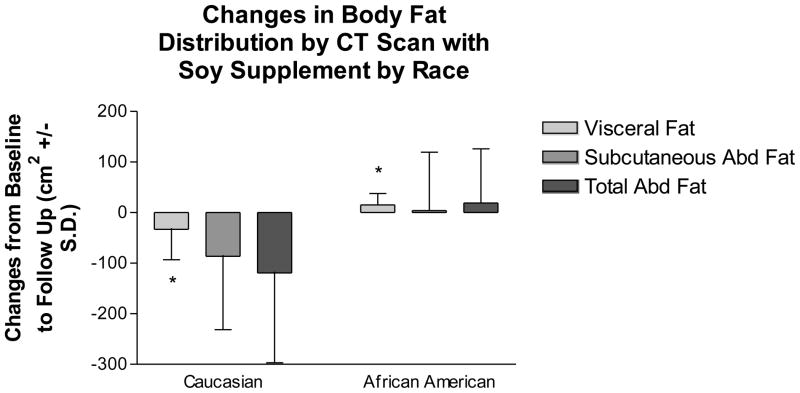

We compared changes in body composition and body fat distribution with regard to self-reported race using an interaction term along with race and treatment variables in a linear model. The only outcome variables with significant interaction terms were change in weight (p=0.0171) and change in visceral fat (p=0.0320) (Figures 3a and 3b). African American women lost 1.8 kg, compared to a gain of 0.8 kg in Caucasian women with the soy supplement (Figure 3a). However, body fat distribution improved more for Caucasian women, who lost 33 ± 60.1 cm2 visceral fat compared to a gain of 15.1 ± 22.6 cm2 for African American women (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Changes in body composition (3a) and body fat distribution (3b) in women taking the soy supplement by self-reported race. Values are means ± S.D. African-American women lost more weight as measured by DXA than Caucasian women on the supplement. Caucasian women lost more visceral fat as measured by CT scan than African-American women on the supplement.

The effect of the soy supplement compared to placebo on glucose and insulin metabolism as determined by the hyperglycemic clamp is shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences in first or second phase insulin secretion between treatment groups over time. However, second-phase insulin secretion increased in the placebo group [5086 (−6432 – 13455) pmol/min], but decreased in the soy group [−2188 (−11000 – 5540) pmol/min], (p=0.11 for differences between groups). Similarly, there were no differences between groups in estimates of peripheral glucose disposal or endogenous glucose production.

Table 3.

Effect of Soy Isoflavones on Hyperglycemic Clamp Outcomes, Inflammation Markers, Adipokines, Lipids. and Macronutrients

| Change in Outcome Variable over 3 months | Placebo (n=16) | Soy (n=17) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Phase Insulin Secretion AUC (pmol/min) | 16.6 (−172–960) | −211 (−2215–1329) | 0.5256 |

| Second Phase Insulin Secretion AUC (pmol/min) | 5086 (−6432–13455) | −2188 (−11000–5540) | 0.1509 |

| Endogenous glucose production (mg/min) | 11.3 (−16.4–36.9) | −3.5 (−92.1–57.8) | 0.5886 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 0.12 (0–1.6) | −0.07 (−1.33–0.08)* | 0.0342 |

| CRP (ng/ml) | 4903 (−719–15464) | 396.3 (−8252–9104) | 0.2140 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | −0.2 (−0.08–0.07) | −0.1 (−0.66–0.15) | 0.3307 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.0 (−14.5–14.0) | 6.0 (−6.0 – 30.0) | 0.2721 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 0.0 (−12.0–8.5) | 5.0 (−2.0–33.0) | 0.0834 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 3.0 (−8.0–9.0) | 4.0 (2–5) | 0.7334 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 17.0 (−13.0–28.5) | 15.0 (−4.5–28.5) | 0.8811 |

| Total calories (kcal/day) | −135 ± 369 | −205 ± 687 | 0.7200 |

| Fat (kcal/day) | −10 ± 20 | −12 ± 42 | 0.8429 |

| Carbohydrate (kcal/day) | −7 ± 59 | −15 ± 63 | 0.7132 |

| Protein (kcal/day) | −3 ± 23 | −10 ± 27 | 0.4609 |

Data are presented as medians (IQR) for all outcome variables except for total calories, fat, carbohydrate, and protein, which are presented as means (SD).

p<0.05

The effect of the supplement on systemic markers of inflammation and adipokine levels is also shown in Table 3. There were no differences at baseline between treatment groups in any inflammatory marker or adipokine. Treatment with soy isoflavones decreased IL-6 by 2.5% compared to an increase of 7.1% with placebo (p=0.03 for differences between groups). There were no differences between groups in changes for CRP, TNFα, leptin, or adiponectin.

The effect of soy on lipids as measured by serum HDL, LDL, triglycerides, and total serum cholesterol is demonstrated in Table 3. The differences from baseline among and between groups did not meet the threshold of significance.

Neither self-reported physical activity nor macronutrient intake (total calories, fat, protein, and carbohydrates) changed significantly between groups during this short-term study. Changes in the Minnesota Leisure Time Activity for the placebo group (medians with interquartile ranges) was 4.2 (−71.2 – 120.3) and for the soy group was 16.7 (−35.6 – 58.6), p=0.84 for differences between groups. Changes in total calories, fat, carbohydrates, and protein intake were not different between groups during the study (Table 3).

At baseline, serum genistein levels were in the 30–60 nM range, and daidzein levels in the 10–25 nM range (low and not different between treatment groups). Other isoflavone levels were even lower or not detectable. Isoflavone levels increased significantly for the treatment group compared to placebo as expected, with increases of 265% in serum genistein and 10,044% in serum daidzein, compared to no changes with placebo, confirming compliance with treatment (p=0.02 for change in serum genistein for soy supplement group compared to placebo, data not shown).

Comment

We report that a daily soy supplement reduced subcutaneous and total abdominal fat compared to an isocaloric casein placebo in a mixed Caucasian and African American population, confirming our previous findings in a population of exclusively Caucasian women. However, it appears that Caucasian and African American women respond differently to the soy supplement with regard to body composition and body fat distribution. African American women in our study lost more weight compared to Caucasian women on the supplement, but Caucasian women had reduced visceral fat compared to African American women, who had an increase in visceral fat, with the supplement. A reduction in visceral fat may be viewed as particularly beneficial, as this fat depot has been linked closely to cardiovascular disease risk. The loss of lean mass with total weight, as observed in African-American women in our study, is a well-documented phenomenon associated with weight loss23. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a differential effect by race on body composition and body fat distribution with a soy supplement.

The mechanism by which soy supplementation reduced abdominal fat accumulation is unknown. Estrogen receptors α and β have been identified on subcutaneous and visceral fat tissue224, and isoflavones bind to both estrogen receptors α and β. Pharmacologic doses of genistein have been shown to inhibiadipose tissue deposition in mice through the down regulation of several adipose differentiation factors, dependent on the binding of genistein to estrogen receptor β. 25 Regardless of the mechanism, our data suggest that a soy supplement prevented the accumulation of subcutaneous and total abdominal fat.

The reason for the racial differences between Caucasian and African American women with respect to their response to the soy supplement on fat is not clear. African American women have less visceral fat compared to Caucasian women,26 thus Caucasian women have more visceral fat to lose in response to treatment. Isoflavones in the supplement may bind to estrogen receptors in fat, particularly estrogen receptor β. The expression of estrogen receptor β varies by fat depot,24 although its variability by race has not been reported. This differential response by race deserves further study.

We were unable to find significant differences between placebo and supplement with regard to glucose and insulin metabolism in our study. However, we found a trend toward a significant improvement in second phase insulin secretion favoring the soy supplement over placebo. Similar to our findings, Villa and colleagues found no difference in peripheral glucose disposal between genistein and placebo using euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp methodology.27 In contrast, Jayagopal and colleagues reported that in postmenopausal type 2 diabetics, soy supplementation resulted in significant decreases in fasting insulin, insulin resistance, and HbA1c.28 It is possible that the effects of soy isoflavones on glucose and insulin metabolism vary depending on the glycemic status of the individual.

We found that the soy supplement reduced IL-6. Since IL-6 is produced by subcutaneous abdominal fat,25 one might expect that IL-6 would decrease if abdominal fat decreased. In addition, isoflavones could down regulate IL-6 through its transcriptional factor, nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kB), known to be susceptible to ER-mediated down regulation.30–32 We are unaware of any other reports regarding the effect of soy isoflavones on IL-6 in humans.

Other inflammatory markers, including CRP and TNF-α, were not changed by the supplement, suggesting that the supplement may not have a generalized effect on inflammation. In contrast to our findings, Hall and colleagues reported that a two month isoflavone enriched diet given to women in the U.K. resulted in a modest, though significant decrease in CRP.33 We did not find an effect of our soy isoflavone supplement on CRP. Differences in patient populations and soy isoflavone doses and preparations may be responsible for the variation in CRP outcomes.

Circulating adiponectin and leptin were not affected significantly by the soy supplement in our study. Of interest, there was a trend toward decreased circulating adiponectin with the soy supplement compared to placebo, consistent with a report by Charles and colleagues.14 This decreased adiponectin would seem to be in contrast to the trend toward reduced second phase insulin secretion in our study. However, it is possible that tissue levels of adiponectin do not reflect circulating concentrations. Further studies may clarify this apparent discrepancy.

We did not find a significant effect of the soy supplement on lipids. Several human studies have reported a significant reduction in total and LDL cholesterol with soy supplementation in Caucasian and African Americans34,35,15. In contrast, other studies have not observed a beneficial effect of soy supplementation on lipids36,37. Differences between study outcomes may relate to variability in the soy supplements used, and to possible differences in equol production between individuals in various studies. Further studies are needed to analyze this variability further.

Strengths of our study include its randomized placebo-controlled design, its inclusion of nearly equal numbers of Caucasian and African American participants, and our use of criterion measures to assess body composition and body fat distribution, along with insulin secretion (DXA, CT, and hyperglycemic clamps). We assessed self-reported physical activity and self-reported food intake to determine that changes in these variables between groups during the study were not confounders. In addition, we report the effect of a soy supplement on circulating inflammation markers and adipokines in humans, which has not been well studied. Limitations of our study include its relatively small sample size, which reduced our ability to detect significant differences in insulin secretion; however, significant effects on our primary outcome variables (total abdominal fat and subcutaneous abdominal fat) were noted. A post-hoc power calculation revealed that given the differences we found in our primary fat outcome variables, our study had 76.3% power to detect differences in total abdominal fat, and 75.3% power to detect differences in subcutaneous abdominal fat. In addition, our study was short-term, so it is not clear if the effects of the soy supplement on abdominal fat reduction would persist if the supplement was continued.

In summary, we confirm the benefits of a soy isoflavone supplement in reducing subcutaneous and total abdominal fat in postmenopausal non-diabetic obese Caucasian women, but report that these beneficial effects on body fat distribution may not be apparent for African American women. The benefit to African American women appears to be on total body fat. The effect on fat does not appear to be mediated by a generalized change in circulating markers of inflammation, and it is not clearly associated with benefits in glucose and insulin metabolism. Future studies should address the long-term implications of soy isoflavone dietary supplementation to reduce the age and menopause-related gain in central fat.

Acknowledgments

NIH K24 RR019705, and M01 RR00032.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mosca L, Banka CL, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1230–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters HW, Westendorp IC, Hak AE, et al. Menopausal status and risk factors for cardiovascular disease. J Intern Med. 1999;246:521–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthews KA, Meilahn E, Kuller LH, Kelsey SF, Caggiula AW, Wing RR. Menopause and risk factors for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:641–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909073211004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kannel WB, Hjortland MC, McNamara PM, Gordon T. Menopause and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:447–52. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-85-4-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toth MJ, Tchernof A, Sites CK, Poehlman ET. Effect of menopausal status on body composition and abdominal fat distribution. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:226–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wildman RP, Mancuso P, Wang C, Kim M, Scherer PE, Sowers MR. Adipocytokine and ghrelin levels in relation to cardiovascular disease risk factors in women at midlife: longitudinal associations. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:740–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sites CK, Toth MJ, Cushman M, et al. Menopause-related differences in inflammation markers and their relationship to body fat distribution and insulin-stimulated glucose disposal. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:128–35. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02934-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang HM, Chen SW, Zhang LS, Feng XF. The effects of soy isoflavone on insulin sensitivity and adipocytokines in insulin resistant rats administered with high-fat diet. Nat Prod Res. 2008;22:1637–49. doi: 10.1080/14786410701869598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rachon D, Vortherms T, Seidlova-Wuttke D, Wuttke W. Effects of dietary equol on body weight gain, intra-abdominal fat accumulation, plasma lipids, and glucose tolerance in ovariectomized Sprague-Dawley rats. Menopause. 2007;14:925–32. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31802d979b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner JD, Zhang L, Shadoan MK, et al. Effects of soy protein and isoflavones on insulin resistance and adiponectin in male monkeys. Metabolism. 2008;57:S24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sites CK, Cooper BC, Toth MJ, Gastaldelli A, Arabshahi A, Barnes S. Effect of a daily supplement of soy protein on body composition and insulin secretion in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:1609–17. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atteritano M, Marini H, Minutoli L, et al. Effects of the phytoestrogen genistein on some predictors of cardiovascular risk in osteopenic, postmenopausal women: a two-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3068–75. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greany KA, Nettleton JA, Wangen KE, Thomas W, Kurzer MS. Consumption of isoflavone-rich soy protein does not alter homocysteine or markers of inflammation in postmenopausal women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62:1419–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charles C, Yuskavage J, Carlson O, et al. Effects of high-dose isoflavones on metabolic and inflammatory markers in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2009;16(2):395–400. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181857979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen JK, Becker DM, Kwiterovich PO, et al. Effect of soy protein-containing isoflavones on lipoproteins in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2007;14:106–14. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000229572.21635.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R. Glucose clamp technique: a method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:E214–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.237.3.E214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sites CK, L'Hommedieu GD, Toth MJ, Brochu M, Cooper BC, Fairhurst PA. The effect of hormone replacement therapy on body composition, body fat distribution, and insulin sensitivity in menopausal women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2701–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kashyap S, Belfort R, Gastaldelli A, et al. A sustained increase in plasma free fatty acids impairs insulin secretion in nondiabetic subjects genetically predisposed to develop type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:2461–74. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Cauter E, Mestrez F, Sturis J, Polonsky KS. Estimation of insulin secretion rates from C-peptide levels. Comparison of individual and standard kinetic parameters for C-peptide clearance. Diabetes. 1992;41:368–77. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjostrom L, Kvist H, Cederblad A, Tylen U. Determination of total adipose tissue and body fat in women by computed tomography, 40K, and tritium. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:E736–45. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1986.250.6.E736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albanes D, Conway JM, Taylor PR. Validation and comparison of eight physical activity questionnaires. Epidemiology. 1990;1:65–71. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schakel SF, Buzzard IM, Gebhardt SE. Procedures for estimating nutrient values for food composition databases. J Food Comp and Anal. 1997;10:102–14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaston TB, Dixon JB, O'Brien PE. Changes in fat-free mass during significant weight loss: a systematic review. Int J Obes. 2007;31(5):743–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedersen SB, Bruun JM, Hube F, Kristensen K, Hauner H, Richelsen B. Demonstration of estrogen receptor subtypes alpha and beta in human adipose tissue: influences of adipose cell differentiation and fat depot localization. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;182:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00557-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penza M, Montani C, Romani A, et al. Genistein affects adipose tissue deposition in a dose-dependent and gender-specific manner. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5740–51. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beasley LE, Koster A, Newman AB, et al. Inflammation and Race and Gender Differences in Computerized Tomography-measured Adipose Depots. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009 doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villa P, Costantini B, Suriano R, et al. The Differential Effect of the Phytoestrogen Genistein on Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Postmenopausal Women: Relationship with the Metabolic Status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jayagopal V, Albertazzi P, Kilpatrick ES, et al. Beneficial effects of soy phytoestrogen intake in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1709–14. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morisset AS, Huot C, Legare D, Tchernof A. Circulating IL-6 concentrations and abdominal adipocyte isoproterenol-stimulated lipolysis in women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1487–92. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galien R, Garcia T. Estrogen receptor impairs interleukin-6 expression by preventing protein binding on the NF-kappaB site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2424–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gong L, Li Y, Nedeljkovic-Kurepa A, Sarkar FH. Inactivation of NF-kappaB by genistein is mediated via Akt signaling pathway in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:4702–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Sarkar FH. Inhibition of nuclear factor kappaB activation in PC3 cells by genistein is mediated via Akt signaling pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2369–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall WL, Vafeiadou K, Hallund J, et al. Soy-isoflavone-enriched foods and inflammatory biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk in postmenopausal women: interactions with genotype and equol production. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1260–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.6.1260. quiz 1365–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allison DB, Gadbury G, Schwartz LG, et al. A novel soy-based meal replacement formula for weight loss among obese indivduals: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:514–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crouse JR, 3rd, Morgan T, Terry JG, et al. A randomized trial comparing the effect of casein with that of soy protein containing varying amounts of isoflavones on plasma concentrations of lipids and lipoproteins. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2070–76. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.17.2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson JW, Hoie LH. Weight loss and lipid changes with low-energy diets: comparator study of mild-based versus soy-based liquid meal replacement interventions. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24:210–16. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2005.10719467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Z, Hong K, Saltsman P, et al. Long-term efficacy of soy-based meal replacements vs an individual diet plan in obese type II DM patients: relative effects on weight loss, metabolic parameters, and C-reactive protein. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:411–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]