Abstract

Grandparents throughout sub-Saharan Africa have shown immense courage and fortitude in providing care and support for AIDS-affected children. However, growing old comes with a number of challenges which can compromise the quality of care and support they are able to provide, particularly for children infected by HIV and enrolled on antiretroviral therapy (ART) programmes. For ART to be effective, and for infected children not to develop drug-resistance, a complex treatment regimen must be followed. Drawing on the perspectives of 25 nurses and eight grandparents of HIV-infected children in Manicaland, eastern Zimbabwe, we explore some of the challenges faced by grandparents in sustaining children's adherence to ART. These challenges, serving as barriers to paediatric ART, are poverty, immobility, deteriorating memory and poor comprehension of complex treatments. Although older HIV-infected children were found to play an active role in sustaining the adherence to their programme of treatment by contributing to income and food generating activities and reminding their guardians about check-ups and drug administration, such contribution was not available from younger children. There is therefore an urgent need to develop ART services that both take into consideration the needs of elderly guardians and acknowledge and enhance the agency of older children as active and responsible contributors to ART adherence.

Keywords: paediatric AIDS, anti-retroviral therapy, adherence, elderly guardians, Zimbabwe

Introduction

The last couple of years has seen unprecedented progress in the availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in sub-Saharan Africa (WHO, UNAIDS, & UNICEF, 2009), not least in Zimbabwe where both primary care and hospital-based HIV services are reaching some of the most isolated communities. As a result 215,000 (57% of those living with AIDS) people are estimated to access ART in Zimbabwe, with more people enrolling every day (UNAIDS, 2010). A survey carried out in 2008 estimates that 13% of all patients receiving HIV care from the health services in Zimbabwe are between 0 and 19 years of age, of which 33% are aged 0–4; 25% are between 5–9 years; 25%, 10–14 years; and 17%, 15–19 years (Ferrand et al., 2010). As the fight against HIV and AIDS continues, it is imperative that antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) are accessible and that virologic suppression remains high. Virologic efficacy, or “good adherence,” is better achieved if patients stick to their ART regimen for 95% of the time (Attaran, 2007). Good adherence minimises resistance to affordable first-line drugs (Barth et al., 2011; Tanuri et al., 2002) but has been identified as a challenge for HIV-infected children and adolescents on ART (Arrive et al., 2005; Bikaako-Kajura et al., 2006; Fassinou et al., 2004, 2010; Polisset, Ametonou, Arrive, Aho, & Perez, 2009; Weigel et al., 2009). The Zimbabwean survey carried out by Ferrand and colleagues (2010) asked clinic staff from all ART distribution centres in the country about common problems faced by children and adolescents in accessing and adhering to HIV care regimens. They found that for young children (0–5), malnutrition, lack of appropriate drugs, erratic drug taking and hospital visits, orphanhood and caregiver issues (e.g., elderly, ill or unsupportive caregivers) were common challenges to children's adherence to ART. For adolescents (10–19), erratic drug taking was also a major obstacle to adherence, as was lack of disclosure and poor use of counselling and psychosocial services (Ferrand et al., 2010). With the objective of developing an understanding of these obstacles to ART adherence, as well as investigating the interconnections between obstacles to ART adherence and the age of children's caregivers, our focus will be on children who have outlived their parents and live with elderly guardians who also act as their treatment partner.

Although elderly people have been found to play a crucial role in providing care and support for adults infected with HIV (Knodel & Zimmer, 2007), this is the first study to explore the caring role of elderly guardians in sustaining the ART adherence of children. Whilst many studies have already explored the care and living arrangements of orphaned children and their elderly guardians, these studies have a tendency to highlight how elderly guardians selflessly take on the burden of caring for orphaned and AIDS-affected children – often at the expense of their own health and well-being. Elderly guardians for example are reported to struggle with financial difficulties (Nyambedha et al., 2003) and suffer from psychosocial distress (Boon, James et al., 2010; Boon, Ruiter et al., 2010; Oburu & Palmerus, 2003, 2005; Ssengonzi, 2007). Whilst this may certainly also be the case of the elderly guardians participating in this study, we believe there is a need to be realistic about the capabilities of elderly guardians, particularly in relation to their role in sustaining the ART adherence of HIV-infected children under their care – often under very difficult conditions. Furthermore, we also believe that such studies only give one side of the story. Reflecting dominant ideological understandings of children as passive beings in need of adult support and guidance (cf. Hutchby & Moran-Ellis, 1998; James, Jenks, & Prout, 1998), they generally begin with the view of children as the problem (“the burden”) and adults as the solution (“the burdened”). We seek to move beyond this conception, building on studies that have highlighted the reciprocity of care and support within such households (Abebe & Skovdal, 2010; Skovdal, 2010). Although elderly guardians do – very importantly – provide orphaned and HIV-infected children with a home and place of belonging, their old age, illness and fragility may limit their contribution towards income and food generation, meaning they depend on the contribution and active participation of children in sustaining their livelihoods (Skovdal, 2010) and in some cases health (Skovdal, Ogutu, Aoro, & Campbell, 2009).

In this paper we extend this line of thinking by examining the challenges faced by elderly guardians –and the participation of children themselves – in sustaining the ART adherence of HIV-infected children under their foster care. This is an area of concern only previously mentioned in passing (e.g., Ferrand et al., 2010; Meyers et al., 2007; Raiman, Michaels, Nuttall, & Eley, 2008). In South Africa for example, both Meyers et al. (2007) and Raiman et al. (2008) report that elderly guardians have practical difficulties in administering ARV medication due to their compromised visual and arithmetic skills. It is against this background, and in our interest to support elderly guardians in their efforts to sustain ART adherence in children, that we seek to explore the question: what challenges do elderly guardians face in contexts of poverty, AIDS and limited social services as they act as the treatment partners of children on ART? In exploring this question we hope gain knowledge that can help us develop programmes that better support the efforts of elderly guardians to provide the best possible treatment support for children under their care.

Methodology

This research forms part of an on-going study which was granted ethical approval from the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (A/681) and Imperial College London (ICREC_9_3_13). Informed and written consent was gathered from all research participants with the agreement that their identities would not be revealed. Pseudonyms have therefore been used throughout.

Study population and sampling

The study was conducted in three rural communities in Manicaland province of eastern Zimbabwe. The province is characterised by high levels of poverty and HIV. The three rural communities involved in this study are all served by rural hospitals or health clinics that distribute ART. This paper draws on the perspectives of 25 nurses and eight elderly guardians of children enrolled onto an ART programme. Although 30 guardians of children with HIV participated in the larger study, these eight guardians (the only guardians over the age of 50 participating in our study) all referred to their old age as a major physical and economic constraint to children's ART adherence and therefore qualify for inclusion in this paper. All guardians of HIV-infected children were recruited through a mix of purposeful, snowball (using village community health workers) and opportunistic (self-selected informants) sampling, and in so doing actively sought to identify and recruit some elderly guardians. The age of the elderly guardians (all female) ranged from 52 to 79, with a mean age of 61.

The 25 nurses participating in this study were recruited from three health clinics on the basis of their willingness to participate. The nurses had a variety of experiences and came with different backgrounds, right from primary care and outreach programmes to HIV testing, ART distribution and palliative care. The nurses tend to live within the compounds of the hospital and have received training on the administration of paediatric ART. The mean age of the 25 nurses (11 female, 14 male) participating in the study was 40.

Data collection and analysis

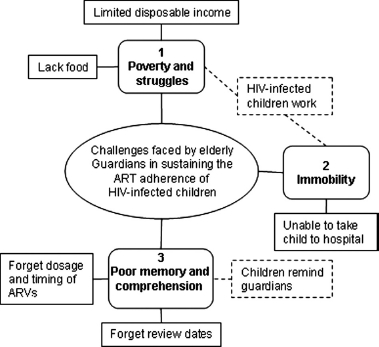

The data for this study were collected in October and November 2009. Four experienced fieldworkers conducted 26 in-depth interviews (18 with nurses and eight with elderly guardians) and one focus group discussion with seven nurses in the local Shona language. The semi-structured topic guides used for the elderly guardians covered informants’ personal background, their experiences of AIDS, stigma and being a treatment partners as well as problems and facilitators of children's ART access and adherence. Individual and group nurse interviews used the same topic guide. The topic guide asked the nurses about their experiences in providing HIV treatment for children, including barriers and facilitators, as well as their interaction with treatment partners. With permission, the interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed and translated into English by the field-workers. To ensure the accuracy of transcription and translation, 20% of all transcripts were randomly selected to undergo a quality check, including back-translation. No inaccuracies were identified. Individual and group interview transcripts of both nurses and elderly guardians were imported into the qualitative software package Atlas.Ti for thematic content analysis (Flick, 2002). Data collected by the two study methods and populations were pooled and analysed collectively to provide a holistic and comprehensive understanding of patterns (core themes) within the data corpus (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Using a social constructionist perspective, we sought to map out features of the collectively constructed representational field which shaped both nurses’ and carers’ understandings and actions, rather than seeking to document attitudes conceived of as properties of individuals (Gaskell, 2001). Following the steps of Attride-Stirling's (2001) thematic network analysis, text segments were first coded with an interpretative title, which were clustered into higher order, or primary themes. The outcome of this thematic network analysis is presented in Figure 1, which highlights the three primary themes that address the research question of this paper and make up the structure of our presentation of findings.

Figure 1.

Thematic network: challenges (lessened by children's agency, see dotted boxes) faced by elderly guardians in sustaining the ART adherence of HIV-infected children.

Findings

To contextualise our findings within the lived realities of the elderly guardians acting as treatment partners, Table 1 gives detail to the household composition of each of the eight guardians participating in this study. What Table 1 encapsulates is the impact of AIDS on families and the fostering role of older people. Several guardians had lost their husbands and children and were now the foster parents of their grandchildren, young nieces or nephews. As such, the table also highlights that elderly people were not necessarily alone in creating a supportive context for children on ART; there were often other children in the household who could help out. The HIV-positive children on ART in the eight households described in Table 1 were all on first-line treatment (combination of Stavudine, Lamivudine and Nevirapine), which was administered on a weight-based system in tablets. Although syrups, which are more easily administered to younger children, are available, these are hard to access in Zimbabwe.

Table 1.

Household characteristics of elderly guardians providing HIV care for children.

| Elderly guardian | Household characteristics |

| Nokutenda, age 79 | Nokutenda stays with five grandchildren between the ages 4–12, of which one 8–year-old girl is HIV– positive and on ART. Nokutenda's husband, two sons and two daughters have all died and she survives through subsistence farming. |

| Sandra, age 59 | Sandra lives with her husband, mother– in-law, her sick daughter and her three grandchildren. One of her grandchildren, a 16–year-old girl, is HIV-positive and on ART. Sandra and her husband provide for the household through subsistence farming. |

| Carolyn, age 56 | Carolyn stays with her brother and 6– year-old niece, both of whom are HIV– positive and on ART. The 6–year-old girl is separated from her older brother who is under the care of other family members. Carolyn's son occasionally visits and supports Carolyn financially. |

| Tanyaradzwa, age 70 | Tanyaradzwa stays with her two great grandchildren, including a 4–year-old boy who is HIV-positive and on ART. Her grandson (children's father) has gone to the city to look for work. The wife of her grandson has passed away. Tanyaradzwa receives help from her 10– year-old granddaughter to care for the boy. |

| Violet, age 67 | Violet stays with three grandsons, the oldest being 12, HIV-positive and on ART. Her son (father of her grandchildren) and her daughter-in-law have both died. Violet sustains the household through subsistence farming. |

| Joanna, age 52 | Joanna stays with her ill son, her sister's 20–year-old daughter and her brother's three boys, of which a 9–year-old is HIV-positive and on ART. Joanna works as a sales woman, buying and selling goods at the local market. |

| Cellestine, age 54 | Cellestine and her husband live with their three grandchildren, of which the oldest, all –year-old girl is HIV– positive and on ART. Cellestine and her husband provide for the household through subsistence farming. |

| Marjorie, age 53 | Marjorie stays with her 6–year-old grandson who is HIV-positive and on ART. She stayed with her daughter and son-in-law until recently when they both passed away. Marjorie sustains herself and her grandson through subsistence farming. |

Overall, great progress has been made in achieving children's access and adherence to ART in this context, however, as we will now illustrate, HIV-infected children who live with their elderly guardians may face some barriers to optimal ARV adherence that are unique to their care arrangements.

Poverty and struggles

Households made up of elderly guardians and orphaned or AIDS-affected children are particularly vulnerable to poverty and related struggles. One such example includes the struggles faced by Joanna who is too old to work and has difficulties paying for the schooling and clothing of her foster children.

The problems I am facing are monetary including schooling and clothing. All these are solely my responsibility at the same time I am too old to work and this has been a major problem. (Joanna (52), elderly guardian)

Such struggles often result in children having to carry the responsibility of contributing to household sustenance, and on occasion HIV-infected and ill children are forced to engage in work. As one nurse commented:

There are those who want to take advantage of these children. Maybe the child will be the only grandchild but he sends him to the grinding mill, to fetch water, to water the garden some being used that you feel pity. There was a case of a sick child, the grandmother was saying a-aah she works she even goes to fetch firewood. That child died. (Peter (35), nurse)

In response to the poverty and struggles faced by ARV users in this context, a number of nongovernmental organisations were reported to provide them with food aid, minimising pressures on sick children to engage in income and food generating work as well as providing them with a nutritious diet to support their treatment.

Some of these children are being cared for by elderly guardians so they lack food but now that problem has been met because a lot of organizations are distributing food in the area. (Jackie (36), nurse)

Immobility

We have already alluded to the fact that some elderly guardians are unable to generate food and income. But in what other ways can their immobility compromise children's adherence to ART? ARV users in this context need to go for check-ups and pick up their drugs at a designated health facility on a monthly basis. Each visit costs US$1, covering the administrative costs of the check-up, which, coupled with potential transport costs, can be a challenge for elderly people to pay. But the immobility of some elderly guardians can also prevent them from accompanying their children to their monthly review dates. This is particularly the case with young children who need to be carried.

Like me at my age, to think of going there on foot or even to carry the child on my back, it's impossible and for me to get someone to help me take the child to hospital can be impossible. I can't even think of carrying a child on my back at my age, if I fail to get anyone who is kind enough to help me then there is little I can do. (Cellestine (54), elderly guardian)

Other times the sheer distance can present as a barrier for guardians who had difficulties walking. They were also more likely to get sick and be periodically immobile, preventing the child from attending its review date and pick up ARV supplies.

The health of some of the children who stay with their elderly guardians is not good and sometimes elderly people are not strong enough to come with the children to the clinic the distance might be near but the elderly guardian can't walk the child will end up defaulting. (James (36), nurse)

Elderly women, they would be coming from far away. For her to send the child by herself is not possible, for her to send someone with the child is difficult because of the issue of stigma, so they will remain at home and miss the appointment. If there was a mobile facility that would have helped. (Roselyn (57), nurse)

However, carers repeatedly stated the strength of their commitment to ensure that children attended their monthly hospital review on the appropriate date.

The only thing that can stop me would be if I fall ill myself, and I fail to find anyone to escort my child to the hospital, As for my chores at home, I will always leave them behind and take the child to hospital first. (Nokutenda (79), elderly guardian)

Poor memory and comprehension

For some elderly guardians, remembering the review dates was a bigger challenge than immobility. Several informants spoke of difficulties faced by elderly guardians in remembering drug review dates, often only returning to the hospital when drugs had run out, resulting in a delay in the child's treatment.

Sometimes these children will be staying with their grandmothers and these grandmothers are old, so they may sometimes forget the review dates, when they are and how many weeks they should wait before going back, so they end up forgetting everything, hence they delay to go and get the children's pills. (Marjorie (53), elderly guardian)

Forgetfulness can also mean that children are not reminded to take their drugs at a regular interval, with elderly guardians forgetting when the last drug was taken. This, coupled with a relative complicated administration of drugs, may compromise the child's treatment.

Some of them stay with grandparents who are too old, and who confuse the time or the drugs the child has to take. (Evelyn (29), nurse)

However, occasionally other household members, and children in particular, play an active role in helping their elderly guardians remember when drugs need to be taken.

The other children are the ones who are reminding me, they remind him to take the tablets and they also tell me that he has taken the tablets and is now leaving for school. (Nokutenda (79), elderly guardian)

No I do not forget to give the child the drugs. Even if I was to forget this kid himself would remind me. You hear him saying: “Granny its six o'clock, time for my medication”. (Violet (67), elderly guardian)

A number of nurses spoke of problems in communicating with elderly guardians. They said the guardians often failed to understand the complexity of the child's treatment regimen. Nurses go to great lengths to ensure that treatment partners – who play a primary role in facilitating the treatment regimen of ARV users – have the tools and knowledge to facilitate child adherence, but these are often inadequate for elderly people who are unable to read and write. This is particularly a problem if the child in their care is still young and cannot assist in keeping notes for their treatment schedule.

Most of the children we have who are on ART are cared for by people who are very old. We give people adherence calendars that they should fill in, but what if she can't write, if she is 80 something years? The child may be around four or six years, so for her to write down and to properly administer the drugs may be challenging. She doesn't even know the name of the drug she is giving the child. You would have told her the name but she won't remember it, she just knows that the child is on medication, that's very tricky. Some of them they do not have middle aged people close to them to help them with taking care of the child, so its really a challenge. (Collin (27), nurse)

As Miriam, a nurse, explains, many of the elderly guardians are aware of their limitations and actively remind the child to be alert to the advice they receive from the nurses.

It's a challenge when you have to explain to an elderly person, especially the issue of food, I would be emphasizing what the child needs to eat, I will explain it to the child and I will do it thoroughly so that the child will remind the grandmother. The grandmother will actually call the child to be alert to what we will be saying, you realize that the child is now taking responsibility for all this yet it should be the other way round. When it comes to food, you will hear that the child has eaten only once, yet s/he should be eating more often than this for the drugs, so it's a challenge, there is a problem with elderly caregivers. (Judith (34), nurse)

Discussion

The findings presented in this paper first and foremost highlight the commitment and dedication elderly people show in ensuring that children under their care comply with the rigid treatment regimens associated with ART, an asset previously identified in Cambodia (Williams, Knodel, Kim, Puch, & Saengtienchai, 2008) and Thailand (Knodel, Kespi chayawattana, Saengtienchai, & Wiwathwanich, 2009). In this paper we have illustrated that deteriorating mobility, memory and comprehension of complicated treatment plans, coupled with poverty in a context of limited social welfare and government support, make it difficult for some elderly guardians to sustain the treatment of HIV-infected children in their care – presenting a key challenge for paediatric ART adherence. Our findings suggest that support for elderly carers should address both their poverty-and age-related needs. Although these needs are interrelated, they require different interventions. Age-related challenges refer to their physical limitations (deteriorating memory, comprehension and mobility) and poverty-related challenges refer to their lack of income and food, necessitating the infected child to engage in income generating activities beyond what is good for them. Whilst the obstacles faced by elderly guardians took precedence in this paper, our informants did also highlight potential strategies that can help elderly people in their role as treatment partners of HIV-infected children. These included the distribution of food aid, encouraging children's agency and participation in the treatment, stigma-reduction programmes, increasing social support networks, mobile health facilities and improving the physical access to health facilities (e.g., constructing satellite clinics to reduce the distance).

It is clear that elderly people are ideally positioned as treatment partners to HIV-infected children by virtue of their living arrangements and associated emotional attachments (Knodel et al., 2009). However, as some of the age-related challenges identified in this paper highlight, such arrangements could benefit from externally facilitated support. HelpAge International (2008) recommend that elderly carers, especially women, must have access to legal advice, financial support and literacy programmes, so that they can access entitlements for themselves and those in their care. Failure to address the rights of elderly people will undermine their ability to care for others. One way to address poverty-related challenges is to make financial support, such as social pensions, available. Social pensions targeting poor and vulnerable elderly people have been identified as a feasible intervention alleviating the impact of HIV and AIDS (Kakwani & Subbarao, 2007; Schatz & Ogunmefun, 2007). These pensions, in the form of monthly cash transfers to elderly people, could enable already committed elderly guardians to use the funds on direct and indirect expenses related to the treatment of children under their care (such as drugs or hospital fees, transport and food). Child-support grants, as seen in South Africa (Case, Hosegood, & Lund, 2005) and Kenya (Bryant, 2009) also have the potential to alleviate some of the poverty-related challenges identified in this paper as barriers to the adherence of ART in children.

In addition to cash transfers, social networks can be strengthened through community mobilisation and community health workers (or hospital outreach staff) to monitor and address the challenges specific to households with elderly guardians (Skovdal, Mwasiaji, Webale, & Tomkins, 2008; Skovdal, Mwasiaji, Webale, & Tomkins, 2010). Such services could encompass providing elderly people with locally appropriate mobility aids and alarmed watches to ensure timely follow-ups and medication as well as making information about treatment regimens accessible to elderly people. One of our informants also highlighted the need for mobile health services, suggesting the need to decentralise ART dispensing to local clinics as well as making outreach staff mobile so that they can reach immobile elderly guardians out in the communities.

This study also highlighted that in contexts of limited support, the agentic capabilities of older children (over the age of 10 as defined by Ferrand et al., 2010) play a key role in coping with some of the challenges identified in this paper. Older children help with income and food generating activities and remind guardians about review dates and the administration of drugs. Therefore, to ensure the adherence to ART in children under the care of elderly guardian, there is an urgent need for HIV services to embrace and involve both the children and their elderly guardians in HIV programme planning. Older children living in the household, whether HIV-positive themselves or the older siblings of a younger-positive child, need to be acknowledged as contributing agents to ART adherence. Not only will such an acknowledgement of children's agency help us move beyond unhelpful understandings of children as a “burden” to “burdened” elderly people, it also highlights the importance of involving older children in the treatment process.

To conclude, we believe that much more needs to be done to advocate for policies and programmes that take heed of some of the challenges and resources identified in this paper and argue for more family/ household centred HIV services that take account of the elderlies’ needs for support, and acknowledge and enhance the agency of older children as active and responsible contributors to ART adherence. However, as this is a new area of research, further investigation into the prevalence of elderly treatment partners and the obstacles they are facing (e.g., segregated by the children's age) as well as the experiences of elderly guardians in other settings is urgently needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the research participants. We also extend our gratitude to Cynthia Chirwa, Samuel Mahunze, Edith Mupandaguta, Reggie Mutsindiri, Kundai Nhongo, Zivai Mupambireyi and Simon Zidanha for translation, transcription, research and logistic assistance. This work was generously supported by the Wellcome Trust.

References

- Abebe T., Skovdal M. Livelihoods, care and the familial relations of AIDS-affected children in eastern Africa. AIDS Care. 2010;22(5):570–576. doi: 10.1080/09540120903311474. iFirst. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120903311474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrive E., Anaky M.F., Wemin M.L., Diabata B., Rouet F., Salomon R., Msellati P. Assessment of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in a cohort of African HIV-infected children in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2005;40(4):498–500. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000168180.76405.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attaran A. Adherence to HAART: Africans take medicines more faithfully than North Americans. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e83. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research. 2001;1(3):385–405. [Google Scholar]

- Barth R.E., Tempelman H.A., Smelt E., Wensing A.M.J., Hoepelman A.I., Geelen S.P. Long-term outcome of children receiving antiretroviral treatment in rural South Africa: Substantial virologic failure on first-line treatment. 2011. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. Epub ahead of print doi:10.1097/ INF.1090b1013e3181edl092af1093. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bikaako-Kajura W., Luyirika E., Purcell D.W., Downing J., Kaharuza F., Mermin J., Bunnell R. Disclosure of HIV status and adherence to daily drug regimens among HIV-infected children in Uganda. AIDS Behaviour. 2006;10:S85–S93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon H., James S., Ruiter R.A.C., van den Borne B., Williams E., Reddy P. Explaining perceived ability among older people to provide care as a result of HIV and AIDS in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2010;22(4):399–408. doi: 10.1080/09540120903202921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boon H., Ruiter R.A.C., James S., van den Borne B., Williams E., Reddy P. Correlates of grief among older adults caring for children and grandchildren as a consequence of HIV and AIDS in South Africa. Journal of Aging and Health. 2010;22(1):48–67. doi: 10.1177/0898264309349165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant J. Kenya's cash transfer program: Protecting the health and human rights of orphans and vulnerable children. Health and Human Rights in Practice. 2009;11(2):65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A., Hosegood V., Lund F. The reach and impact of child support grants: Evidence from KwaZulu-Natal. Development Southern Africa. 2005;22(4):467–481. [Google Scholar]

- Fassinou P., Elenga N., Rouet F., Laguide R., Kouakoussui K.A., Timite M., et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapies among HIV-1-infected children in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. AIDS. 2004;18:1905–1913. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200409240-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand R., Lowe S., Whande B., Munaiwa L., Langhaug L., Cowan F., et al. Survey of children accessing HIV services in a high prevalence setting: Time for adolescents to count? Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88:428–434. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.066126. doi:410.2471/BLT. 2409.066126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick U. An introduction to qualitative research. 2nd ed. London: SAGE; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell G. Attitudes, social representations and beyond. In: Deaux K., Philogene G., editors. Representations of the social. Oxford: Black-well; 2001. pp. 228–241. [Google Scholar]

- HelpAge. Stronger together-supporting the vital role played by older people in the fight against the HIV and AIDS pandemic. London: HelpAge International; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchby I., Moran-Ellis J. Children and social competence: Arenas of action. London: Washington, DC: Falmer Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- James A., Jenks C., Prout A. Theorising childhood. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kakwani N., Subbarao K. Poverty among the elderly in Sub-Saharan Africa and the role of social pensions. Journal of Development Studies. 2007;43(6):987–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J., Kespichayawattana J., Saengtienchai C, Wiwathwanich S. Older-age parents and the AIDS epidemic in Thailand: Changing impacts in the era of antiretroviral therapy. UNESCAP; 2009. Retrieved from http://www.unescap.org/ESID/psis/Ageing/publications/O1der_age_parents_and_AIDS.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J., Zimmer Z. Older persons AIDS knowledge and willingness to provide care in an impoverished nation: Evidence from Cambodia. Asia Pacific Population Journal. 2007;22:11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers T., Moultrie H., Naidoo K, Cotton M., Eley B., Sherman G. Challenges to pediatric HIV care and treatment in South Africa. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;196(s3):S474–S481. doi: 10.1086/521116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedha E., Wandibba S., Aagaard-Hansen J. “Retirement lost”–the new role of the elderly as caretakers for orphans in Western Kenya. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2003;18:33–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1024826528476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oburu P., Palmerus K. Parenting stress and self-reported discipline strategies of Kenyan caregiving grandmothers. International Journal of Behavioural Development. 2003;27(6):505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Oburu P., Palmerus K. Stress related factors among primary and part-time caregiving grandmothers of Kenyan grandchildren. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2005;60(4):273–282. doi: 10.2190/XLQ2-UJEM-TAQR-4944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polisset J., Ametonou F., Arrive E., Aho A., Perez F. Correlates of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected children in Lomé, Togo, West Africa. AIDS and Behaviour. 2009;13:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9437-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiman S., Michaels D., Nuttall J., Eley B. A 4-pronged approach to addressing antiretroviral adherence in children: A paediatric pharmacy perspective. SA Pharmaceutical Journal. 2008;75(8):18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E., Ogunmefun C. Caring and contributing: The role of older women in rural South African multi-generational households in the HIV/AIDS Era. World Development. 2007;35(8):1390–1403. [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M. Children caring for their ‘Caregivers’: Exploring the caring arrangements in households affected by AIDS in Western Kenya. AIDS Care. 2010;22(1):96–103. doi: 10.1080/09540120903016537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M., Mwasiaji W., Morrison J., Tomkins A. Community-based capital cash transfer to support orphans in Western Kenya: A consumer perspective. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2008;5(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Skovdal M., Mwasiaji W., Webale A., Tomkins A. Building orphan competent communities: Experiences from a community-based capital cash transfer initiative in Kenya. 2010. Health Policy and Planning. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1093/heapol/czq039. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Skovdal M., Ogutu V., Aoro C., Campbell C. Young carers as social actors: Coping strategies of children caring for ailing or ageing guardians in Western Kenya. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69(4):587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssengonzi R. The plight of older persons as caregivers to people infected/affected by HIV/AIDS: Evidence from Uganda. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2007;22:339–353. doi: 10.1007/s10823-007-9043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanuri A., Caridea E., Dantas M.C., Morgado M.G., Mello D.L.C., Borges S., et al. Prevalence of mutations related to HIV-1 antiretroviral resistance in Brazilian patients failing HAART. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2002;25(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(01)00249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Zimbabwe-2010 Country Progress Report. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2010. Retrieved from http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2010/zimbabwe_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Weigel R., Makwiza I., Nyirenda J., Chiunguzeni D., Phiri S., Theobald S. Supporting children to adhere to anti-retroviral therapy in urban Malawi: Multi method insights. BMC Pediatrics. 2009;9 doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-45. Art. No. 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, UNAIDS, & UNICEF. Towards universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDs interventions in the health sector-Progress Report (September 2009 ed.) Geneva: WHO Press; 2009. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/tuapr_2009_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Williams N., Knodel J., Kim S., Puch S., Saengtienchai C. Overlooked potential: Older-age parents in the era of ART. AIDS Care. 2008;20(10):1169–1176. doi: 10.1080/09540120701854642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]