Abstract

Two qualitative methodologies were used to develop a life course typology of individuals who had been exposed to sexual violence. Interview narratives of 121 adult women and men who participated in qualitative study of women’s and men’s responses to sexual violence provided the data. The authors combined a narrative approach (holistic-content and holistic-form analysis) to describe the life courses of the participants and a qualitative person-oriented approach (cross-case analysis) to identify meaningful sub-groups within the total sample. The six groups are: (a) life of turmoil, (b) life of struggles, (c) diminished life, (d) taking control of life, (e), finding peace in life, and (f) getting life back to normal. This work exemplifies a promising strategy for identifying sub-groups of violence-exposed individuals within a heterogeneous sample. Such a typology could aid the development of treatment approaches that consider both the substance and the structure of an individual’s life course, rather than target one specific type of violence.

Sexual violence, defined as all sexual activity for which consent has not been obtained or cannot be given freely (The Centers for Disease Control [CDC] and Prevention, 2007), is a significant public health problem. A national telephone survey conducted in the United States between 2001 and 2003 revealed that 1 in 59 adults experienced unwanted sexual activity in the prior 12 months, and 1 in 15 had experienced forced sex during their lifetime (Basile, Chen, Black, & Saltzman, 2007). A myriad of negative sequelae are associated with sexual violence. Acute consequences may include injuries, sexually-transmitted infections, pregnancy, and acute stress responses (CDC, 2007; Marx, 2005). Long-term outcomes may include chronic pain, headaches, gastrointestinal distress, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, substance use, sexual problems, high-risk health behaviors and interpersonal difficulties (Briere & Jordan, 2004; CDC; Marx).

Significant strides have been made in identifying the prevalence and consequences of violence. Some experts suggest, however, that progress in understanding the complexity of interpersonal victimization has been hindered because researchers tend to focus on one specific type of violence (e.g., childhood sexual abuse, adult sexual assault) rather than the more common manifestation of multiple types of violence that occur concurrently (Kilpatrick, 2004; Saunders, 2003; Williams, 2003). Most childhood sexual abuse, for example, is accompanied by emotional or physical abuse (Saunders).

Many individuals are exposed to violence at different points throughout their lives; those who experience childhood sexual abuse, for example, are at considerable risk for victimization later in life (Williams, 2003). Several quantitative, longitudinal studies have linked violence experiences over time, yet researchers seldom explore these experiences from a life course perspective (Williams, 2003). Researchers from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, for example, reported that for 5,649 young adult heterosexual males who had been followed from 1995 to 2001, sexual abuse as a child was associated with sexually coercive behavior in adulthood, and that this relationship was mediated by early sexual initiation (Casey, Beadnell, & Lindhorst, 2008). In a life course approach, robust life histories would be obtained from such individuals, and the relationships revealed in the quantitative analysis would be explored in the context of individuals’ unique life patterns. Such approaches would further inform our understanding of pathways of recovery.

Research approaches that capture the multi-dimensional and longitudinal nature of violence are needed to inform clinical practice. Whereas most empirically-validated therapies are developed to treat the effects of single-episode assaults with specific outcomes (e.g., rape leading to PTSD), few are available for individuals who have experienced multiple episodes of violence and exhibit complex trauma responses (Briere & Jordan, 2004). Ecological approaches to trauma recovery, however, do address how individuals overcome trauma and achieve wellness (Harvey, 1996). Resilience is a central factor in ecological models. Some individuals exposed to trauma do not become symptomatic. Those that do differ in the expression of symptoms, the meaning they attribute to the violence, and the paths they take to recovery (Harvey, 2007). As Harvey argues:

These differences reflect a complex interplay of many influences, including the nature and chronicity of the events to which they have been exposed; demographic factors such as age, race, class, and gender; neurobiological mediators of hardiness and vulnerability; the influence and stability of relevant social, cultural, and political contexts; and any number of ecological factors that support or impede access to natural support, comforting beliefs, and trauma-informed clinical care. (13)

In ecological models, resilience to trauma is explained by person-environment interactions. Theorists propose that individuals are embedded in their social context, and a variety of contextual forces influence trauma recovery (Harvey, 2007). Yet, humans are also influence their environment. Five pathways to wellness have been identified, based on the ecological perspective: (a) forming wholesome early attachments, (b) acquiring age- and ability- appropriate competencies, (c) exposure to settings that favor wellness outcomes, (d) having an empowering sense of being in control of one’s fate, and (e) coping effectively with stress. (Cowen, 1994).

Person-oriented research methods offer one possibility for addressing the “complex problem of experiencing multiple types of [violence] throughout the lifespan” (Kilpatrick, 2004, p. 1222) and are consistent with ecological models of trauma. Bergman and Magnusson (1997) contrast variable-oriented and person-oriented approaches to research on human development. In variable-oriented approaches, variables representing theoretical constructs are the primary analytic units, and researchers seek to examine theoretically-derived relationships among the constructs. In person-oriented approaches, the individual as a whole is the analytic unit, and researchers seek to uncover “patterns of individual characteristics that are relevant for the problem under consideration” (p. 293). Nurius and Macy (2008) argue that much of the research on violence-exposed women uses traditional variable-oriented approaches to examine relationships among abuse-related variables (e.g., the severity of an assault) and outcome measures (e.g., depression), but because violence experiences are heterogeneous, research is also needed to assess “meaningful patterns” (p. 389) of person-level variables within samples. Nurius and Macy advocate the use of quantitative research methods to examine relationships among salient variables at the person level, thereby enabling heterogeneous samples to be divided into sub-groups with important characteristics in common.

Macy, Nurius, and Norris (2007) used such a person-oriented method to uncover distinct multivariate profiles of college women who had experienced sexual assault based on the presence or absence of four risk factors: prior victimization, alcohol consumption, relationship expectancies of the assailant, and assertive precautionary habits. Using latent profile analysis, they identified four distinct profiles (i.e., victimization-relationship, relationship-protective, alcohol-low else, and alcohol-victimization). Similarly, Jonzon and Lindblad (2006) used a combined person-oriented and variable-oriented approach to investigate patterns of risk and protective factors as they relate to health outcomes in adult women who had experienced childhood sexual abuse. Using cluster analysis, they identified six groups with different patterns or risk and protective factors (i.e., multi-risk, support compensation, intermediate, low risk, scarce resources, and good coping).

Person-oriented methods, therefore, can address heterogeneity within samples and life course methods can address violence over the course of a lifespan. This article reports the results of a research project in which two qualitative methodologies were used to develop a life course typology of individuals who had been exposed to sexual violence. The authors combined a narrative approach (holistic-content and holistic-form analysis) and a qualitative person-oriented approach (cross-case analysis) to enable the identification of sub-groups of violence-exposed individuals based on several characteristics of their life courses, rather than just the type of violence they have experienced. Because the sample for this research was drawn from on on-going research study, this study (referred to as the parent project) is first discussed.

The Parent Project: Women’s and Men’s Responses to Sexual Violence

Interview narratives of 121 adult women and men who participated in a qualitative study entitled “Women’s and Men’s Responses to Sexual Violence” (referred to as the parent project) provided the data for the current study. The purpose of the parent project is to develop a mid-range theory that describes, explains, and predicts women’s and men’s responses to sexual violence.

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the researchers’ university, participants were recruited by community sampling methods (Martsolf, Courey, Chapman, Draucker, & Mims, 2006). Fourteen communities of varying ethnic and economic composition in Northeast Ohio were selected as sampling units on the basis of US Census data. Research associates canvassed the communities to select sites to place study fliers and to conduct interviews. Fliers were placed at locations that individuals were likely to gather or pass through (e.g., local businesses, libraries, community agencies, transportation stops, coffee shops). The research associates also discussed the study with neighborhood and religious leaders, proprietors, and community-based social service professionals, many of whom agreed to promote the study.

Potential participants were invited to call a toll-free line to leave their name and contact information. A research associate contacted them by phone and conducted a brief screening interview to ensure that they met inclusion criteria. Participants were invited to participate if they (a) were aged 18 or older, (b) had experienced sexual violence at some time in their lives, (c) had not experienced severe emotional problems (e.g., suicidality, psychosis) within the past year, and (d) were not involved in an abusive relationship that would make participation in the study dangerous. Two-hundred and one (201) participants made an initial call to the toll-free line. Among the 80 individuals who called the toll-free line but were not included in the final sample, most did not leave sufficient contact information, could not be reached by screeners, or failed to attend a scheduled interview. Several were screened out of the study because they had not experienced sexual violence, but no participants were screened out for safety concerns.

Interviews were scheduled at community sites in the participants’ neighborhoods. After the participants signed an informed consent document, the research associates conducted semi-structured interviews. Participants were asked to describe the sexual violence they experienced, other events that co-occurred with the violence, how they responded to the violence, how the violence affected their lives, and how they coped or healed from the violence. The participants were paid $35.00 for their time and travel. All the interviews were taped and transcribed, and data were entered in the N6 qualitative data-management computer program (QSR, 2002).

Constructing the Typology

Sample

The transcripts of the 121 participants in the parent study were analyzed for this study. Sixty-four of these participants were women, and 57 were men. Thirty-two of the women were African American, 27 were Caucasian, 2 were multi-racial, and 3 did not report race. Twenty-five of the men were Caucasian, 17 were African American, 5 were multiracial, 1 was Asian, 1 was Hispanic, and 8 did not report race. The participants ranged in age from 18 to 62; 69 were single, 20 were married, 22 were separated or divorced, 1 was partnered, 1 was engaged, 1 was widowed, and 7 did not report marital status. Sixty-five participants were employed in a variety of occupations, including sales, service, education, health care, and construction. Twenty-four of the participants were unemployed, 5 were disabled, 17 were students, 2 were retired, and 8 did not report employment status. Sixty-three reported an income under $10,000/year, 22 reported incomes between $10,000 and $30,000/year, 14 reported incomes between $30,000 and $50,000/year, 16 reported incomes above $50,000/year, and 6 did not report income.

Data Analysis

The research team conceptualized participants’ narratives as life stories. Several scholars have suggested that people make sense of their lives in the form of stories. Bruner (1990) argued that humans have a natural “readiness or predisposition to organize experience into a narrative form, into plot structures and the rest” (p. 43). McAdams and colleagues (1997) suggested that one’s identity … “may itself be viewed as an internalized and evolving life story … complete with settings, scenes, characters, plots, and themes” (p. 678). Riessman (2008) stated, “When biographical disruptions [such as violence] occur that rupture expectations for continuity, individuals make sense of events through storytelling” (p. 10). The interviews for the parent project were semi-structured and focused on the sexual violence that the participants had experienced. Nonetheless, the team felt that the interviews served as a “narrative occasion” (Riessman, 2008, p. 23) in which participants provided robust accounts of multiple types of violence and described their life courses in detail to contextualize the violence.

The life stories were analyzed by the research team, which consisted of 10 nurse researchers who were involved in the parent project at its various stages. During weekly and/or monthly meetings, the team held in-depth discussions about each narrative; ideas raised during these discussions were recorded for an audit trail and used in the analytic processes described below. In narrative analysis (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber, 1998; Reissman, 2008), multiple researchers analysis the data to enrich interpretations rather than to achieve coding consensus; reliability checks are therefore not applicable. Underlying uniformities in the data are determined through on-going discussions by a team of researchers. The authors constructed the final typology.

Narrative Analysis

The primary analytic strategy of the parent project was constant comparison analysis, in which narratives were segmented into text units, which were then compared to form categories (Schwandt, 2001). The current study used the same data set, but worked to retain the integrity of the narratives as a whole. Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber (1998) refer to this as a holistic, rather than a categorical, reading of text. Holistic-content and holistic-form analyses of the narratives were conducted (Lieblich et al.).

Holistic-Content Analysis

This type of analysis “takes into consideration the entire story and focuses on its content” (Lieblich et al., 1998, p. 15). To capture the content of the narratives, we identified the major themes of each transcript, as well as the overarching theme that reflected each participant’s life course. Examples of overarching themes included unending violence, redemption, taking control of one’s life, and so forth.

Holistic-Form Analysis

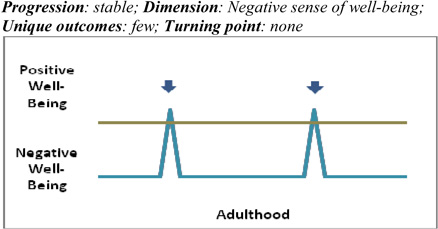

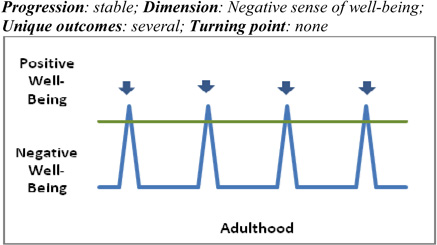

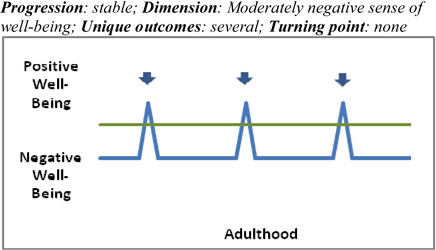

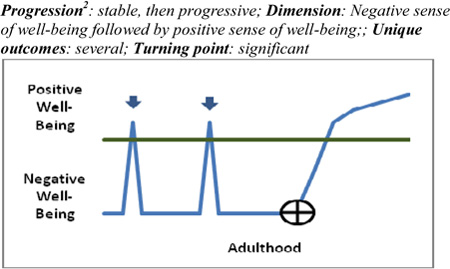

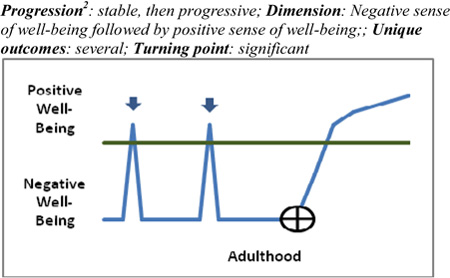

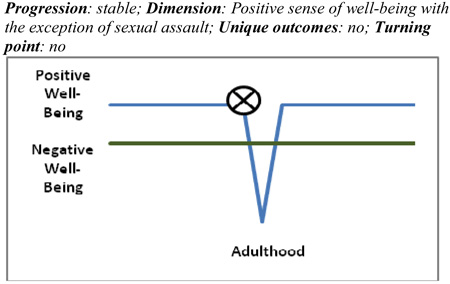

This analysis “looks at a complete life story but focuses on its formal aspects rather than its content” (Lieblich et al., 1998, p. 16). Graphing the plot progression of narratives is one form of holistic-form analysis. Gergen and Gergen (1988) identified three prototypical narrative forms of life stories based on movement toward the attainment of a valued goal. These forms are: the stability narrative (progress to goal remains unchanged), the progressive narrative (steady progress to the goal), and the regressive narrative (a continuous moving away from the goal). For this study, we graphed the plot progression that reflected each participant’s life course as an adult using general well-being as the assumed valued goal. A horizontal line was used for a stable narrative, an upward sloped line for a progressive narrative, and a downward sloped line for a regressive narrative. Using Gergen and Gergen’s approach, the plot can be graphed on an evaluative dimension that indicates whether the life story reflects positive or negative experiences. Stories of life experiences or time periods that reflected a generally positive sense of well-being were plotted in the top half of the graphs; those that reflected a negative sense of well-being were plotted in the lower half. Each narrative, therefore, was graphed as a combination of plot progressions that varied between positive and negative dimensions of well-being.

Form-analysis also considers other characteristics of the plot, such as turning points and unique outcomes. A turning point is an experience that results in a meaningful transformation in character or self-view (Clausen, 1998; Wethington, 2003). Life experiences in the participants’ narratives were coded as turning points if they (a) were exceptional events that occurred at specific points in time, (b) were experienced as memorable and intense, (c) were either quite positive or negative, and (d) resulted in a drastic change in life pattern. A unique outcome is an event “that would not be predicted by a problem-saturated narrative” (Freedman & Combs, 1996, p. 67), but that displays the hidden strength, ability to resist oppression or vitality of the narrator. Unlike turning points, unique outcomes may be minor, barely-noticed events that nonetheless define the contour of a life course. Life experiences in the participants’ narratives were coded as unique outcomes if they: (a) were events that occurred at specific points in time, (b) were positive experiences embedded in a life course that was otherwise troubled, (c) were not described as memorable and intense, and (d) did not result in a drastic change in life pattern. We plotted turning points as steep slopes and unique outcomes as narrow peaks.

Cross-Case Analysis

Once the content and form of the narratives had been examined, a cross-case analysis (Miles & Huberman, 1994) was used to develop the life-course typology. This analysis allows researchers to inspect “cases in a set to see whether they form in clusters or groups that share certain patterns or configurations” (Miles & Huberman, p. 174). A meta-matrix, a chart that organizes data from multiple cases in a standard format, was produced. Each row represented a case (a participant) and each column represented analytic categories related to the content and form analyses (e.g., themes, plot progression, turning points, unique outcomes). Data from the transcripts that were pertinent to these categories were placed in the appropriate cells. Repeating patterns in the columns were uncovered, and cases that shared repeating patterns in the columns were juxtaposed by moving rows. Patterns were used to cluster cases that were similar to one another, but qualitatively different in some fundamental way from other cases. Our goal was to identity a parsimonious number of groups without forcing groupings or producing extremely finely-grained distinctions. Thus, both the data and principles of theory development drove the final number of clusters. Once the cases were clustered and the groups had been determined, the data in each column were examined to discern patterns and construct a “typical story” for each group.

Results

The typology is depicted in Table 1, and the six groups are described below. The groups were named by themes that best described the common life courses of the members. For each group, the table depicts a demographic summary of the members, a summary of common life pattern, a graph of the common plot progression, and a brief description of a particularly representative “exemplar” case. The exemplars are referred to by pseudonyms, and non-substantive details that might reveal their identity are changed. The transcripts of nine participants did not provide enough information for them to be included in a group, either because of poor audiotape quality or because interviews had not yielded a good description of their life courses.

Table 1.

Life Course Typology of Adults Who Experienced Sexual Violence

| Groups | Common Life Patterns | Common Plot Progressions ⬇ = unique outcomes1; ⊕ = turning point;⊗ = sexual assault |

Exemplars |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Group 1: Life of Turmoil N = 32 12 M 20 F 9 AA 17 C 2 MTO 4 NR Average Age = 43 Modal Income = <10k |

- on-going sexual, physical, and emotional abuse in childhood and adulthood - dysfunctional family-of- origin/chaotic early life - problem-saturated lives as adults - no examples of agency - no social support |

|

Steve is a 22-year old Caucasian man. He experienced CSA between the ages of 3 and 17 by his grandfather, stepfather, cousins and neighbors. Steve described his early family life as chaotic; in addition to the sexual violence he experienced, his parents separated when he was three, after which his mother remarried and the family moved frequently. His mother was not responsive when he tried to tell her about the abuse. As an adult, he has been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, has had difficulties with drugs and alcohol, and has had several altercations with the police. He has been incarcerated on several occasions. He struggles with his sexuality, revealing that he considers himself to be bisexual but hopes to “grow out of it.” |

|

Group 2: Life of Struggles N = 24 13 M 11 F 11 AA 11 C 2 NR Average Age = 38 Modal Income = <10k |

- on-going sexual, physical, and emotional abuse in childhood and adulthood - dysfunctional family-of-origin/chaotic early life - problem-saturated lives as adults, with some positive life experiences - few examples of agency - some social support |

|

Tonya is a 22-year-old African-American woman. She experienced CSA by multiple family members, including her grandfather and her uncle. She was also raped as a teen by a man from whom she was buying drugs. Her family life was chaotic and abusive. Her grandmother told her she was a whore when she disclosed the abuse by her grandfather. As an adult, she has been hospitalized many times and has had many suicide attempts. She is now in a relationship with a man she describes as a “rock” and has learned in therapy that the abuse was not her fault. She continues to struggle from psychiatric problems. She was unkempt, disheveled, and exhibited some disorganized thinking during the interview. |

|

Group 3: Diminished Life N = 20 10 M 10 F 8 AA 8 C 1 MTO 2 NR 1 Hispanic Average Age = 38 Modal Income = <10k |

- some on-going abuse in childhood by family members; often one-time assaults by those outside the family - some unhappiness as children, but minimal chaos and dysfunction in family-of-origin - as adults, function well but experience anxiety, depression, bitterness, low-self-esteem - unacknowledged agency - some social support, but limited trust in others |

|

Charlene is a 35-year old African-American woman who was fondled at age 10 on one occasion by an older brother. She did not report any dysfunction in her family-of-origin, although she did feel that her brother was favored over her and she would be blamed if the two of them argued. Her father died when she was a teenager and she recalled feeling abandoned. As an adult, she is employed as a teacher. She does not report any major problems as an adult, but does feel that the sexual abuse incident with her brother left her wary of men. She indicated that she did not date men until she was in her 30s and often dresses in a masculine way to protect herself. |

|

Group 4: Taking Control of Life N = 18 3 M 15 F 13 AA 5 C Average Age = 42 Modal Income = <10k |

- on-going abuse in childhood and adulthood - dysfunctional family-of origin/ chaotic early life - problem-saturated lives as adults, with some positive life experiences - significant life event (often a personal triumph) that prompts making life changes, especially taking control of one’s life - social support |

|

Jenny is a 35-year-old Caucasian woman who was raped as a teenager by a boyfriend, Jim. He continued to sexually and physically abuse her, resulting in significant bodily injury. At one point, she was hospitalized after an assault. When she was released, Jim came to her house, tried to threaten her with a blow torch, and called her mother a bitch. After this, Jenny decided she had reached her breaking point and would never again be hurt by Jim. She said, “I physically beat him and his friend up. I was small but I did…” She also described a later scene when she stood her ground: “He did come into my store [a convenience story] once when I was nineteen or twenty, and I told him I will not wait on you. I will call the police. Get out of my store. And he left.” After this, she created a positive life for herself. She established a loving relationship with an intimate other and takes a number of precautions to ensure that her children stay healthy. She believes she is “70 percent healed.” |

|

Group 5: Finding peace Group 5: Finding peace N = 13 7 M 6 F 6 AA 4 C 1 MTO 2 NR Average Age = 36 Modal Income = <10k |

- on-going abuse in childhood and adulthood - dysfunctional family-of- origin and chaotic early life - problem-saturated lives as adults, with some positive life experiences - significant life event (often spiritual in nature) that prompts making significant life changes, especially gaining a sense of peace - social/spiritual support |

|

Joe is a 52-year-old African-American man who was raped as a teenage. His early family life was troubled; at age 16 his mother was shot as she worked in a bar and he went to “live on the streets.” His life after that involved drug abuse and drinking and being “in and out of prison.” About three years ago, he developed a relationship with God that changed him “dramatically and completely.” Since then, he has not used drugs or alcohol or smoked cigarettes. He now works as a tutor and community organizer. He states, “I am a walking testimony to the fact that God is alive and well and doing miracle business.” |

|

Group 6: Getting back to normal Group 6: Getting back to normal N = 8 8 M 0 F 5 C 2 MTO 1 NR Average Age = 25 Modal Income = 30–50k |

- a single episode of sexual violence that did not involve physical violence - both childhood and adulthood are described as “normal” |

|

Andre was a 27-year-old multi-racial man who, as a young adult, was grabbed by an acquaintance who attempted to sexually assault him. He told his family, who were “supportive and said I had to be careful and stuff like that.” He indicated that nothing remarkable was happening in his life at the time of the assault:“Just basic normal years, you know, just working, had my own place, doing pretty well. My car was like pretty hot.” He also indicated that his childhood included “the normal bumps and bruises but other than that it was fine. I don’t have any real complaints” Of the assault, he said, “I mean it’s in the past, it happened you know, it’s done and over with, there’s nothing you can do to change it. I mean it’s unfortunate it happened but I mean you know I got to deal with it. I mean I can’t go back in time and you know rewrite it. |

Key: M = Male, F = Female, AA = African American, C = Caucasian, MTO= More than One Race, NR= Not Reported

The number of unique outcomes portrayed in each graph represent whether the unique outcomes were generally rare or common in each group; the number of unique outcomes that appeared in each transcript were not counted.

Groups 4 and 5 have plot progressions with similar structures. However, the nature of the turning points and subsequent life patterns differed significantly. Group 4 experienced a turning point that was typically a personal triumph and that resulted in their taking control of their lives. Group 5 experienced a turning point that was often spiritual in nature and that resulted their finding peace.

Group 1: Life of Turmoil

Holistic-Content Analysis

The common overarching theme of this group was termed life of turmoil. The participants focused on the turmoil they experienced throughout their lives and at the time of the interview. The term turmoil was chosen to capture both the magnitude of the groups’ troubles as well as the sense of chaos that was central to their narratives.

Members of this group had experienced sexual violence, as well as physical and emotional abuse, at a number of points throughout their lives. Most revealed experiences of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) of long duration perpetrated by a number of individuals, often family members, and episodic violence as adults by intimate partners. In addition, several reported a number of one-time assaults by family members, acquaintances and strangers. One female participant (age not reported) exemplifies the extensiveness of sexual violence experienced by this group. She had experienced on-going CSA by a male cousin at age 7, CSA by both her step-father and a male babysitter later in childhood, CSA by her brother at age 12, and rape by an intimate partner as an adult.

Participants in this group also described parental absence, alcoholism, unstable living situations, inadequate out-of-home placements, and criminal behavior in their families-of-origin. For many, their adult lives resembled their childhoods as they continued to live in chaotic, abusive, and exploitive environments. They had experienced alcohol and drug abuse; prostitution; mental illness; suicide attempts; multiple psychiatric hospitalizations; criminal behavior and incarceration; serious physical health problems, including HIV/AIDS; multiple unplanned and early pregnancies; homelessness; and perpetration against others. They provided very few examples in which their own actions or initiatives garnered positive or desired results. The narratives were devoid of descriptions of others who supported or befriended the participants.

Holistic-Form Analysis

The participants in this group indicated that they had made no progress toward healing or recovery from the violence they had experienced, and continued to suffer from on-going maltreatment, physical problems, and emotional distress. Several lamented that they did not expect their life courses to change. Participants expressed a lack of hope with statements such as, “I am never going to get over the stuff I’ve been through,” or, “It seems like there is no answer for me, no solution.” These narratives revealed no notable turning points and very few unique outcomes. The common plot of this group is thus graphed as a stable narrative in the negative dimension of well-being, with no turning points and few unique outcomes.

Group 2: Life of Struggles

Holistic-Content Analysis

The common theme of this group was termed life of struggles. The term struggle was chosen to capture the many trials this group endured as well as their efforts to overcome their challenges. While members of this group had problem-saturated stories that were similar to those of Group 1, they also had made a number of notable attempts to improve their lives. These attempts, however, were often fleeting and overshadowed by on-going problems.

Like Group 1, Group 2 had experienced sexual violence, as well as physical and emotional abuse, at several points throughout their lives. Most had experienced on-going childhood sexual abuse and sexual violence with intimate others as adults. A few experienced isolated incidents of sexual assault (e.g., rape by strangers) that were particularly brutal.

Group 2 also described much dysfunction in their families-of-origin, including parental substance abuse, criminal activity, and absence. The participants’ adult lives were marked by many problems, including substance abuse, mental health concerns, run-ins with the law, and serious physical health concerns. Unlike Group 1, however, they had had a number of positive life experiences; they described becoming sober, experiencing positive relationships, or achieving success in a job or school program. A 45-year-old man, who was sexually abused by his father and assaulted by male peers, had struggled with drugs and alcohol, convictions for driving while intoxicated, and problems with intimate relationships. Yet, he also earned a college degree, lost 80 pounds, and became a “health nut.”

Such positive life experiences, however, were often short-lived and followed by set-backs. The participants often went back to using substances, were revictimized, dropped out of school, or lost a job. Despite the successes of the participant mentioned above, for example, he remained a problem drinker and had written off “part of my life, the part in which you have relationships.”

Holistic-Form Analysis

Despite their occasional successes, the participants in this group had not made significant and enduring changes in the courses of their lives and had not achieved a lasting sense of well-being. The common plot for this group is, therefore, graphed as a stable narrative in the negative dimension of well-being, with several unique outcomes but no turning points.

Group 3: Diminished Life

Holistic-Content Analysis

The common theme of this group was termed diminished life. These participants focused on how they continued to be plagued by the violence they had experienced, although they typically functioned well and failed to report chaotic life styles, severe emotional disturbances, or high-risk behaviors. The term diminished was chosen to capture their sense that the violence had caused on-going distress and significantly lessened the quality of their lives.

This group was less likely to have experienced both childhood and adult abuse than participants in Groups 1 and 2. While several did experience episodic childhood sexual abuse, many experienced one-time sexual assaults, either as children, teens, or adults. Unlike those in the first two groups, the violence experienced by this group was perpetrated mainly by individuals outside the family (e.g., acquaintances, strangers).

Although some participants described feeling unhappy as children because a parent had left the home or they did not receive the nurturance they desired, Group 3 described less chaos and maltreatment in their families-of-origin than that of participants in Groups 1 and 2. A few, in fact, described their early family lives as “normal.” A 28-year-old man, who had been coerced to have sex by a girlfriend, indicated that his “home life was fine; everyone was sane.”

This group described adult lives that differed significantly from those in Groups 1 and 2. The turmoil and the struggles of the first two groups were not evident in Group 3. The group did indicate, however, that the sexual violence had profoundly affected their lives, but in ways that might not be readily apparent to others. Many had achieved successful lives “on the outside,” but experienced on-going anxiety, depression, chronic sadness, or bitterness “on the inside.” Many lacked self-esteem, trust in others, and the ability to enjoy intimacy. They protected themselves by keeping “their guard up.” Members of this group continued to suffer, even if the assaults occurred long ago. A 48-year-old woman, who was sexually assaulted when she was 11 by home intruders, revealed, “I would say the incident still has a bearing on me; I can’t be alone. I own a gun. I wet the bed.” She captured the main focus of this group’s narratives: “I hurt because it does haunt me.”

Holistic-Form Analysis

Members of this group indicated that they had made no significant progress toward healing; their pain was still as intense as it had been soon after the violence. While their sense of well-being was strongly affected by the violence, their lives continued on a steady course. The common plot for this group is graphed as a stable narrative in the negative dimension of well-being. The plot line, however, is not set as low in this dimension as it is in prior groups; while the participants were distressed, they were not living outwardly troubled lives. There are no turning points and few unique outcomes.

Group 4: Taking Control of Life

Holistic-Content Analysis

The common theme of this group was termed taking control of life. Participants had lives that had been saturated with turmoil or struggles. After a particularly meaningful event or experience, however, they took control of their lives and relationships, began healing from the violence, and created “good lives.”

Similar to those in Groups 1 and 2, Group 4 participants had typically experienced on-going childhood sexual abuse and abuse by an intimate partner. Several had also experienced one-time sexual assaults, either as children or as adults. Some participants described dysfunctional families-of-origin, whereas others denied any significant family disturbances. While several indicated that they were not loved or were harshly disciplined as children, their families were, for the most part, not as chaotic or as violent as those of Groups 1 and 2 members. A few participants spoke of their families in positive terms.

This group initially lived lives as adults that were similar to those in Group 2; they reported psychiatric problems, substance abuse, on-going violence in intimate relationships, HIV/AIDs, and obesity, interspersed with examples of times of health and success. Group 4 participants, however, clearly identified a particular experience, after which they turned their “lives around.” Several participants in abusive relationships with intimate partners “turned around” after an incident that was particularly violent or shaming. A 37-year-old woman described an episode in which an abusive partner choked her and sexually assaulted her. She reacted by stabbing him with a knife. She was arrested, convicted of domestic violence, and jailed. This incident served as her “breaking point;” she indicated that she knew “right then and there” that she and her children had to get away. After being released from jail, she got a restraining order, had a home built for her and her children, and escaped further violence. Some participants suffering from the long-term effects of CSA experienced the turning point after a particular experience in which they decided “enough was enough.” A 29-year-old woman who was sexually molested by her grandfather reported that she became an addict at age 19 and began to “sleep around.” At one point, she saw a videotape on sexual abuse and noticed with alarm that many of the signs of abuse portrayed in the tape were things that she had experienced. She resolved to address the abuse so she would not let her grandfather destroy her life - “because if I did he would win…” She sought counseling and became sober. The participants in this group attributed the changes in their lives to their own efforts and resilience.

Holistic-Form Analysis

These participants experienced a period of time during which they made little progress toward healing or recovery, although they had some positive experiences and temporary successes along the way. Each participant identified a particular point in time associated with a meaningful event or experience after which he/she made significant progress in healing and began to enjoy a sense of well-being. The common plot of this group, therefore, is graphed first as a stable narrative, with some unique outcomes in the negative dimension of well-being, followed by a turning point. The plot is then graphed as a progressive narrative in the positive well-being dimension, reflecting movement toward healing.

Group 5: Finding Peace in Life

Holistic-Content Analysis

The common theme of this group was termed finding peace in life. The participants described finding peace after a lifetime of violence and engaging in high-risk behavior. Like those in Groups 1 and 2, much of their lives had been saturated with turmoil and struggles. Like those in Group 4, they experienced a particularly meaningful event or experience that resulted in major life changes. Whereas Group 4 members had gained a sense of control, Group 5 members had gained a sense of peace and an acceptance of themselves.

The participants had sexual abuse histories that were much like those of members of Groups 1 and 2. Many had experienced childhood sexual abuse and abuse by intimate partners. They had experienced physical abuse, substance abuse, instability, and lack of parental presence or warmth in their families-of-origin. A few, however, described positive family experiences as children and revealed that their parents were loving and attentive.

This group described life patterns in adulthood that were marked by drug and alcohol problems, disturbed interpersonal relationships, HIV/AIDS, and psychiatric disturbances, interspersed with a few positive experiences. The participants claimed to have done many things they were not “proud of,” often involving addictions, but had given up those behaviors after an intense experience that was often spiritual in nature. A 43-year-old man, who had been molested by neighborhood boys as a child and gang raped by hitchhikers as a teen, revealed that he fell into a “life of sin” that included drugs, alcohol, prostitution, and pornography. At one point, he indicated that “God’s Holy Spirit kicked my ass.” He described the spirit reaching out to him: “It was like a light was going off [revealing] ‘you’ve got to stop this [his sins].’” He, like several others in this group, rejected the notion that mental health professionals could facilitate healing. He said, “The only thing that is going to help people is supernatural healing.”

These participants believed that they were enabled to make changes because they were blessed. A 25-year-old woman, who had been molested by a male neighbor, sexually assaulted by a boyfriend, attacked by a male intruder, and emotionally abused by several intimate partners, developed an addiction to marijuana. She reported, “I got pregnant in July, and on August 23rd I became a Christian, and I turned my life over to Jesus…. The day I found out that I was pregnant with my son I stopped smoking pot, I stopped smoking cigarettes, everything, I didn’t do anything at all anymore….” She attributed the change in her life to “God’s will.” She stated, “He loves me that much and he wants me to honor him and bring him glory…”

Holistic-Form Analysis

The progression of the plot of this group is identical to that of Group 4, as these groups’ narratives were structured in the same way with the focus on a turning point. While the substance of their life stories differed (taking control versus finding peace), as did the nature of the turning point (personal versus spiritual), the structures were the same.

Group 6: Getting Life Back to Normal

Holistic-Content Analysis

The common theme of this group was termed getting life back to normal. The participants stressed that sexual violence had interrupted their lives, but that their lives had returned to normal.

Most of the violent incidents experienced by Group 6 members were one-time sexual assaults that occurred in adolescence or adulthood. The perpetrators were typically not family members, but acquaintances, friends, strangers, or dates. The assaults involved fondling, sexual advances, or sexual activities that occurred when the participants were intoxicated or asleep; none were associated with physical violence. Several participants in this group had friends or relatives who assured them the assault was not their fault. They viewed the assault, therefore, as the result of particular circumstances or of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Most viewed their childhoods as “normal” and their families as supportive. The only childhood challenge mentioned was parental divorce. This group also did not discuss problematic adult life patterns. Most of the participants in this group, however, were young adults. Members indicated that their lives were going “smoothly” before the assault, and they wished to get back to their regular routines as quickly as possible. A 20-year old man, who was fondled in a bathroom in a public restroom, indicated that he was reluctant to file a report with police because “I didn’t want my life completely off track the first semester in a new school.”

As a result of the violence, however, the participants became more heedful and cautious. A 27-year-old man, who was assaulted on one occasion by a man he had known in high school, indicated that after the incident he learned to be “real vigilant.” An 18-year-old man, who had been raped by an older woman while he was intoxicated, indicated that he avoids dating situations that “don’t feel right.”

The characteristic that differentiated this group from others was that these participants felt that they had been able to put the violence “behind” them. Although the assault was a traumatic event that they would never forget, they were convinced that it would not have a long-term effect on their lives. A 20-year old man, who had been molested by an older teen on one occasion, indicated, “I just mentally dealt with it and moved on.”

Holistic-Form Analysis

This group’s plot was graphed as a stable life narrative in the positive dimension of well-being with one major spike downward to represent the experience of sexual violence. Unique outcomes were not an issue, as the participants did not see their lives as problem- or abuse-laden. Similarly, there were no significant turning points; they saw their lives as running smoothly before the assault and perceived their lives as going back to normal.

Discussion

The construction of this life course typology offers one approach for identifying sub-groups from a heterogeneous sample of violence-exposed individuals. This approach represents a qualitative equivalent to quantitative person-oriented methods such as cluster or latent profile analysis. Each narrative was unique, and there was much variation of experiences within the groups; however, the narratives of each group shared common substantive and structural characteristics that meaningfully distinguished it from the other groups.

Several aspects of the demographic composition of the groups were notable. Approximately half of the participants reported an income of under $10,000 a year, and the modal income of each group (with the exception of Group 6) was under $10,000 a year. We believe our recruitment procedures resulted in this sample characteristic; we had a positive response to recruitment in urban areas and, in an attempt to include underserved individuals who typically are not well represented in studies of sexual violence (e.g., those living in poverty), we often recruited at social-service venues. The generally low socioeconomic status of the sample might explain why a disproportionate number of participants constituted groups with more life challenges (e.g., life of turmoil, life of troubles).

In addition, Group 6 (getting life back to normal) was unique in that all the participants were male, most were Caucasian, their modal income was $30,000 to $50,000, and they were considerably younger than the other groups (average age was 25). Because this group was small, we cannot fully examine these disparities but speculate that individuals who experience single episodes of violence embedded in an otherwise “normal” life course have different demographic profiles than those who have experienced multiple or particularly severe episodes of violence. Also, due to the sociocultural prescription in our society that men not be “victims” (Draucker & Martsolf, 2006), male participants may have been more likely to conceptualize their violence as an abnormality, rather than as a significant life event that might continue to impact their life course. In addition, because this group was younger, the participants had less time to experience subsequent episodes of violence or life challenges, and because they had more financial and interpersonal resources, they were supported in their efforts to “get back to normal.”

Group 4 (taking control of life) also differed from the other groups demographically as both women and African Americans were over-represented. We hypothesize that this could be because taking control of one’s life often occurred not only in response to the violence itself, but in the context of other forms of life injustices (e.g., domestic violence, racist treatment).

Other researchers have used advanced qualitative methods to determine sub-groups of individuals who share common responses to sexual violence or other life challenges. Thomas and Hall (2008) also used narrative techniques to analyze the life trajectories, turning points, and setbacks of 27 “thriving” survivors of childhood maltreatment. Some patterns of life trajectories identified in their sample were similar to those we uncovered with our holistic-form analysis. For example, Thomas and Hall identified a “lengthy roller-coaster pattern with many ups and downs before assuming a clear upward directionality toward healing” (p. 157). This pattern shared many similarities to the plot progressions of our taking control of life and finding peace in life groups. Thomas and Hall also identified a “struggling pattern, characterized by stagnation or downward progression” (p. 157), which had much in common with the plots of our life of turmoil and life of struggles groups.

Life course typologies have the potential to advance clinical practice. Studies of adult recovery from sexual violence continue to focus primarily on either survivors of adult sexual assault (ASA) (e.g., Frazier, Mortensen, & Steward, 2005; Frazier, Tashiro, Berman, Steger, & Long, 2004; Koss, Figueredo, & Prince, 2002; Littleton, 2007) or adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) (e.g., Brand & Alexander, 2003; Merrill, Thomsen, Sinclair, Gold, & Milner, 2001; Rosenthal, Hall, Palm, Batten, & Follette, 2005; Steel, Sanna, Hammond, Whipple, & Cross, 2004; Whiffen & MacIntosh, 2005; Wright, Crawford, & Sebastian, 2007). Person-oriented methods, both qualitative and quantitative, could be used to identify common subgroups within the populations of individuals who experienced CSA or ASA and clinical strategies that are applicable to each sub-group could be identified. While identifying specific treatment strategies for each of the six groups is beyond the scope of this article, two examples are provided below to demonstrate how a life course typology, informed by an ecological model of trauma recovery (Cowen, 1994; Harvey, 2007), might aid in clinical formulations.

Groups 1 and 2 are constituted by individuals who suffer from complex trauma (Briere & Jordon, 2004), and a staged model of treatment would typically be recommended. Stage models usually involve (a) an early phase that focuses on stabilization and symptom control, (b) a middle phase that focuses on the integration of traumatic memories, and (c) a late phase that focuses on adaptation and development of self and relationships (Draucker & Martsolf, 2006). The life course typology presented in Table 1 would indicate that clinicians use a stage treatment model for individuals Groups 1 and 2 due to their extensive history of violence and their problem-saturated life patterns. The typology would also indicate, however, that early phase strategies would be different for each group. From an ecological perspective, the goal of clinical intervention is to help individuals mobilize their resilient capacities (Harvey, 2007). Because individuals in Group 1 present with essentially no social support and no sense of agency, treatment strategies would focus on the establishment competencies, coping strategies, and an environment that supports wellness (Cowen, 1994) before trauma resolution. On the other hand, for individuals in Group 2, who present with some experiences of social support and instances of agency, strategies should focus on the enhancement of the competencies, coping strategies, and social supports that the individuals have already begun to establish. The structure of the life course of Groups 1 and 2 would also suggest different strategies. Clinicians may enhance early phase work with individuals in Group 1 by bringing forth stories of unique outcomes that have been buried, whereas clinicians may enhance early phase work with individuals in Group 2 by expanding on the unique outcomes stories that have already emerged in their life narratives (Freedman & Combs, 1996). A life course, typology, therefore, can alert clinicians to signs of resilience that might otherwise be hidden.

Groups 4 and 5 also provide an example of how a life course typology could inform treatment planning. The structure of the life course of these two groups were similar; both had a turning point that resulted in significant change in life patterns. The substance, however, of the life course of the two groups differed. Individuals in Group 4 had clearly followed Cowen’s (1996) third pathway to recovery: developing an empowering sense of being in control of one’s fate. Individuals in Group 5, on the other hand, had taken a path that was focused more on achieving peace than control, and the turning point was more likely to a spiritual experience than a personal triumph. As Harvey (2007) has stressed, differences in recovery are the result of a complex interplay of forces, including ecological factors that “support or impede access to natural support [and] comforting beliefs” (p. 13). A typology can reflect how individuals differ substantially on such factors. Whereas clinicians may be called to support the empowerment of individuals in Group 4, individuals in Group 5 will be more likely to rely on sources of spiritual support (e.g., personal spiritual beliefs, relationships with a church community) to aid in their recovery.

While our methods allowed us to describe the life course of the participants retrospectively, we acknowledge that all participants, especially those who were just beginning adulthood, might well experience significant changes in their life courses. It is quite possible, for example, that participants who prior to the interview had primarily struggled, and therefore were placed in Group 2, might well experience a turning point, and therefore be “moved” to Group 4 or 5. In terms of clinical implications, however, this fluidity is not problematic because clinical treatment is always informed by a client’s history, their current functioning, and the potential for change.

A major limitation of this study is that the interviews were not conducted with the purpose of constructing life narratives. To continue this work, we recommend that more formal life interviews be conducted with violence-exposed individuals. McAdams and colleagues (1997), for example, have devised a life-story interview in which participants are asked to divide their lives into main chapters and provide a title and plot summary for each. They then describe eight scenes in detail, including a life-story high point, low point, and turning point. If this approach were used with a large sample, it would allow researchers to develop a more nuanced typology of violence-exposed individuals and to examine each group in more depth.

Acknowledgement

This study is funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research [R01 NR08230-01A1]. Claire B. Draucker, Principal Investigator

Footnotes

The final, definitive version of the article is available at http://online.sagepub.com/.

References

- Basile KC, Chen J, Black MC, Saltzman LE. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence victimization among U.S. adults, 2001–2003. Violence and Victims. 2007;22(4):437–448. doi: 10.1891/088667007781553955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Jordan CE. Violence against women: Outcome complexity and implications for assessment and treatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(11):1252–1276. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman LR, Magnusson D. A person-oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:291–319. doi: 10.1017/s095457949700206x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand BL, Alexander PC. Coping with incest: The relationship between recollections of childhood coping and adult functioning in female survivors of incest. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:285–293. doi: 10.1023/A:1023704309605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J. Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Casey EA, Beadnell B, Lindhorst TP. Predictors of sexually coercive behavior in a nationally representative sample of adolescent males. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008 doi: 10.1177/0886260508322198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention. Understanding sexual violence: Fact Sheet. 2007 Retrieved May 2, 2008 from http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/images/SV%20Factsheet.pdf.

- Clausen JA. Life reviews and life stories. In: Giele JZ, Elder GH, editors. Methods of life course research; Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Cowen EL. The enhancement of psychological wellness: Challenges and opportunities. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1994;22(4):149–177. doi: 10.1007/BF02506861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draucker CB, Martsolf DS. Counseling survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Mortensen H, Steward J. Coping strategies as mediators of the relationships among perceived control and distress in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52(3):267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Tashiro T, Berman M, Steger M, Long J. Correlates of levels and patterns of positive life change following sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(1):19–30. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman J, Combs G. Narrative therapy: The social construction of preferred realities. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen KJ, Gergen MM. Narrative and the self as relationship. Archives in Experimental Social Psychology. 1988;21:17–56. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey MR. Towards an ecological understanding of resilience in trauma survivors: Implications for theory, research, and practice. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma. 2007;14(12):9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jonzon E, Lindblad F. Risk factors and protective factors in relation to subjective health among female victims of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30:127–143. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG. What is violence against women? Defining and measuring the problem. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(11):1202–1234. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Figueredo AJ. Change in cognitive mediators of rape’s impact on psychosocial health across 2 years of recovery. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(6):1063–1072. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieblich A, Tuval-Mashiach R, Zilber T. Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H. An evaluation of the coping patterns of rape victims: Integration with a schema-based information-processing model. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(8):789–801. doi: 10.1177/1077801207304825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macy RJ, Nurius PS, Norris J. Latent profiles among sexual assault survivors: Understanding survivors and their assault experiences. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22(5):520–542. doi: 10.1177/0886260506298839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx BP. Lessons learned from the last twenty years of sexual violence research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20(2):225–230. doi: 10.1177/0886260504267742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martsolf DS, Courey TJ, Chapman TR, Draucker CB, Mims BL. Adaptive sampling: Recruiting a diverse sample of survivors of sexual violence. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2006;23(3):169–182. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2303_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP, Diamond A, de St. Aubin E, Mansfield E. Stories of commitment: The psychosocial construction of generative lives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72(3):678–694. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill LL, Thomsen CJ, Sinclair BB, Gold SR, Milner JS. Predicting the impact of child sexual abuse on women: The role of abuse severity, parental support, and coping strategies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(6):992–1006. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nuris PS, Macy RJ. Heterogeneity among violence-exposed women: Applying person-oriented research methods. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(3):389–415. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. N6 (non-numerical unstructured data indexing researching & theorizing) Qualitative Data Analysis Program. (Version 6 ed.) 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal MZ, Hall MLR, Palm KM, Batten SV, Follette VM. Chronic avoidance helps explain the relationship between severity of childhood sexual abuse and psychological distress in adulthood. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2005;14(4):25–41. doi: 10.1300/J070v14n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riessman CK. Narrative methods for the human sciences. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BE. Understanding children exposed to violence: Toward an integration of overlapping fields. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18(4):356–376. [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt TA. Dictionary of qualitative inquiry. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal MZ, Hall MLR, Palm KM, Batten SV, Follette VM. Chronic avoidance helps explain the relationship between severity of childhood sexual abuse and psychological distress in adulthood. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2005;14(4):25–41. doi: 10.1300/J070v14n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SP, Hall JM. Life trajectories of female child abuse survivors thriving in adulthood. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(2):149–166. doi: 10.1177/1049732307312201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wethington E. Turning points as opportunities for psychological growth. In: Keyes CLM, Haidt J, editors. Flourishing. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Whiffen VE, MacIntosh HB. Mediators of the link between childhood sexual abuse and emotional distress: A critical review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2005;6(1):24–39. doi: 10.1177/1524838004272543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LM. Understanding child abuse and violence against women: A life course perspective. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18(4):441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Wright MO, Crawford E, Sebastian K. Positive resolution of childhood sexual abuse experiences: The role of coping, benefit-finding, and meaning-making. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:697–608. [Google Scholar]