Abstract

The piggyBac transposable element, originally discovered in the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni, has been widely used in insect transgenesis including the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum. We surveyed piggyBac-like (PLE) sequences in the genome of Tribolium castaneum by homology searches using as queries the diverse PLE sequences that have been described previously. The search yielded a total of 32 piggyBac-like elements (TcPLEs) which were classified into 14 distinct groups. Most of the TcPLEs contain defective functional motifs in that they are lacking inverted terminal repeats or have disrupted open reading frames. Only one single copy of TcPLE1 appears to be intact with imperfect 16 bp inverted terminal repeats flanking an open reading frame encoding a transposase of 571 amino acid residues. Many copies of TcPLEs were found to be inserted into or close to other transposon-like sequences. This large diversity of TcPLEs with generally low copy numbers suggests multiple invasions of the TcPLEs over a long evolutionary time without extensive multiplications or occurrence of rapid loss of TcPLEs copies.

Keywords: piggyBac transposable element, diversity, Genome, ITRs, target site preference

1. Introduction

PiggyBac is a Class II transposable element (TE) originally isolated from a baculovirus plaque showing a mutant phenotype in Trichoplusia ni cell culture (Fraser et al., 1983; Cary et al., 1989). The piggyBac element is a highly efficient transformation vector in a diverse range of eukaryotes including more than dozen species spanning five orders of insects: Diptera, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, Coleoptera and Orthoptera (Handler, 2002; Sumitani et al., 2003; Robinson, 2004; Allen, 2004; Shinmyo, 2004). Application of piggyBac-mediated transgenesis has been expanded recently to mammalian cell lines and mice (Ding et al., 2005).

In the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum, piggyBac provides a useful tool for transposon-mediated germline transformation (Berghammer et al., 1999; Lorenzen et al., 2003; Pavlopoulos et al., 2004). This effort has been extended to develop a hybrid dysgenesis system using two different transgenic lines, one carrying a helper construct to provide piggyBac transposase and another carrying a donor construct for transposition (Lorenzen et al, 2007). A simple genetic cross between the donor and the helper lines induces mobilization of the donor element. Large-scale insertional mutagenesis is facilitated by the high efficiency of the transposition activity.

Transposition activity of piggyBac may be influenced by pre-existing related transposable elements, highlighting the importance of characterizing the spectrum of endogenous transposable elements in the genome of a given insect species. Cross-mobilization between related transposable elements has been described previously. Sundararajian et al. (1999) found that hobo transposase could equally mobilize hobo and its related element Hermes in Drosophila melanogater. On the other hand, preexisting mechanisms for suppressing the transposition of endogenous transposable elements may cross-inhibit the activity of vector transposition (Braam and Reznikoff, 1998). We were interested in whether piggyBac-like elements (PLEs) occur in the Tribolium genome and in their evolutionary history, if present. We surveyed the PLEs in the Tribolium genome that has been recently sequenced and assembled at the Human Genome Sequencing Center, Baylor College of Medicine (http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/projects/tribolium/).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Identification of PLE sequences from the database

BeetleBase 2.0 ( http://www.bioinformatics.ksu.edu/beetlebase), which contains 2,341 scaffold sequences, was used for this study. The database was first searched using the TBLASTN algorithm, with the canonical T. ni piggyBac transposase together with AgaPBD2 and HsaPGBD3 transposases as the queries. These three PLEs belong to three major clades of PLEs found in diverse organisms (Sarkar et al., 2003). The PLE sequences identified in the primary screening of the Tribolium genome were then used for another round of database searching to find more PLE copies in the genome with short matching sequences.

2.2. Analysis of PLE sequences

The putative inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) of the PLEs were detected using the program EINVERTED ( http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/seqanal/interfaces/einverted.html) or manually. For multiple copy PLEs, the PLE sequences together with the flanking sequences were aligned with CLUSTALW (Thompson et al., 1994) to confirm the ITR and target site duplications (TSD). The percent GC of PLEs was calculated using GEECEE (http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/seqanal/interfaces/geecee.html). In order to test the presence of potential genes in the flanking regions of each PLE insertion, 5 kb sequences in each direction were used to search against the nonredundant databases at NCBI using BLASTX (www.ncbi.nlm.gov/cgibin/BLAST). The first 25 nt upstream and downstream of each PLE were used to build sequence logos using WebLogo (Crooks et al., 2004). The conceptual translations of the transposase nucleotide sequences were aligned with CLUSTALX. The aligned sequences were used for construction of a phylogenetic tree in MEGA3 (Kumar et al., 2004).

3. Results and discussion

The structure of the T. ni piggyBac element contains an open reading frame encoding a predicted 594-amino acid transposase and perfect 13-bp inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) (Fraser et al, 2000). Wide distribution of homologous sequences has recently been described (Sarkar et al., 2003). In this study, fifty divergent piggyBac-like sequences were gathered from a large diversity of publicly available genome sequences, including fungi, plants, invertebrates and vertebrates. Several different copies of PLEs were recently found in three noctuid species of lepidopteran insects including Heliothis virescens (Zimowska and Handler, 2006, Wang et al., 2006). The Tribolium genome revealed multiple copies of a diversity of PLE sequences in this study.

3.1. PLEs identified in the T. castaneum genome

In homology-based PLE searches of Tribolium genome, a total of 14 distinct types of PLE sequences were identified, and named TcPLE1-TcPLE14. Additional rounds of searching, querying the different types of TcPLEs with higher stringency, found multiple copies of each type. TcPLE3, TcPLE4, TcPLE5, and TcPLE14 were found to have 4, 8, 6 and 4 copies, respectively (see Table 1). Nine elements contain clear boundaries with significant sequence identity (i.e., TcPLE1, TcPLE2, TcPLE3.1, TcPLE4.1, TcPLE5.1, TcPLE5.4, TcPLE6, TcPLE7 and TcPLE14.1), range in size between 1759–7480 bp, and are between 34–38% GC. Some were found to have lost sequence similarity in the middle of the element, although conserved ITRs at each end were clearly identified (TcPLE4.3, TcPLE4.4, TcPLE4.6 and TcPLE4.8). In the remaining TcPLEs, either one or both ITRs were not detected. In many cases sequence similarity was difficult to determine due to the draft nature of the Tribolium genome sequence, which leaves stretches of ambiguous sequence.

Table 1.

Tribolium piggyBac -like elements (TcPLE) sequences identified in the genome sequence (Tcas version2.0).

| Name | Scaffold | Location (nt) | Size (bp) | GC content | ITR Length (bp) | TSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TcPLE1 | Contig4620_Contig8031 | 16624-18885 | 2262 | 37% | 16 | TTAA/TTAA |

| TcPLE2 | Contig5530_Contig1312 | 14344-12586 | 1759 | 36% | 16 | TTAA/TTAA |

| TcPLE3.1 | Contig3124_Contig5424 | 62796-60243 | 2554 | 35% | 15 | TCTA/TATT |

| TcPLE3.2 | Reptig 348 | >2207-<1 | >2207 | 35% | ND | ND |

| TcPLE3.3 | Contig4004_Contig5124 | >2545233-2544285 | >949 | 35% | 15 | /CATA |

| TcPLE3.4 | Contig4522_Contig8630 | >4711-4145 | >567 | 31% | 15 | /TATG |

| TcPLE4.1 | Reptig380 | 11635-14109 | 2467 | 36% | 14 | CTAA/CTAA |

| TcPLE4.2 | Reptig5152 | 363->876 | >514 | 35% | 14 | TTAA/ |

| TcPLE4.3 | Contig4620_Contig8031 | 1103621-1101397 | 2225 | 35%* (953bp) | 14 | TTAA/TTAA |

| TcPLE4.4 | Contig1867_Contig2871 | 65697-63242 | 2456 | 36%* (736bp) | 14 | TTAA/TTAA |

| TcPLE4.5 | Contig8767 | <1-331 | >331 | 33% | 14 | /CTAA |

| TcPLE4.6 | Contig3528_Contig3917 | 530477-528539 | 1939 | 34%* (710bp) | 14 | TTAA/TTAA |

| TcPLE4.7 | Contig4206_Contig7464 | 257074-<256901 | >174 | 36% | 14 | TTAA/ |

| TcPLE4.8 | Contig3368_Contig4509 | 45165-49161 | 3997 | 31%* (374bp) | 14 | TTAA/TTAA |

| TcPLE5.1 | Contig4759 | 4107-1750 | 2358 | 35% | 14 | TTAA/TTAA |

| TcPLE5.2 | Contig3368_Contig4509 | 55035->57227 | >2193 | 36% | 14 | TTAA/ |

| TcPLE5.3 | Contig7258_Contig3558 | 480203-<478166 | >2038 | 36%* (1936bp) | 14 | TTAA/ |

| TcPLE5.4 | Contig1886_3455 | 60862- 63301 | 2440 | 35% | 14 | TTAA/TTAA |

| TcPLE5.5 | Contig7472_Contig6422 | >22134-19801 | >2334 | 34% | 14 | /TTAA |

| TcPLE5.6 | Contig919_Contig5112 | 60370-<58944 | >1427 | 35% | 14 | TTAA/ |

| TcPLE6 | Contig2810_Contig1135 | 306250-309185 | 2936 | 34% | 13 | TTAA/TTTA |

| TcPLE7 | Contig6782_Contig4901 | 10134- 5198 | 4937 | 35%* (2360bp) | 13 | TCAA/TTAA |

| TcPLE8 | Contig1527_Contig3409 | >87135-<85642 | >1494 | 38% | ND | ND |

| TcPLE9 | Contig4515_Contig4818 | <289576->290615 | >1040 | 34% | ND | ND |

| TcPLE10 | Contig2168_Contig6756 | <21664->20636 | >1029 | 33% | ND | ND |

| TcPLE11 | Contig3196_Contig7837 | >3968-<3229 | >740 | 35% | ND | ND |

| TcPLE12 | Contig712 | >5420-<4463 | >958 | 33% | ND | ND |

| TcPLE13 | Contig5324_Contig2241 | >744733-<743453 | >1281 | 37% | ND | ND |

| TcPLE14.1 | Contig7258_Contig3558 | 470054-462555 | 7480 | 38%* (2263bp) | 16 | TTAA/TTTA |

| TcPLE14.2 | Contig7258_Contig3558 | >461426-455137 | >6590 | 38%* (1922bp) | 16 | /TTTA |

| TcPLE14.3 | Contig4620_Contig8031 | 27950->29454 | >1505 | 38% | 16 | TTAA/ |

| TcPLE14.4 | Contig3368_Contig4509 | 65757->65988 | >232 | 35% | 17 | TTAA/ |

No ITRs were identified for TcPLE3.2 and TcPLE8-TcPLE13. For those incomplete PLE copies of TcPLE3-TcPLE5 and TcPLE14, only the terminal locations of the sequences well aligned with complete copies were indicated. For TcPLE8-TcPLE13, only the locations corresponding to the aligned and conserved partial transposase sequences were indicated. TSD: target site duplications. ND: Not determined.

Ambiguous sequences and/or insertion sequences were found within these copies, the base pairs used for GC content analysis excluding these ambiguous or insertion sequences are indicated in brackets.

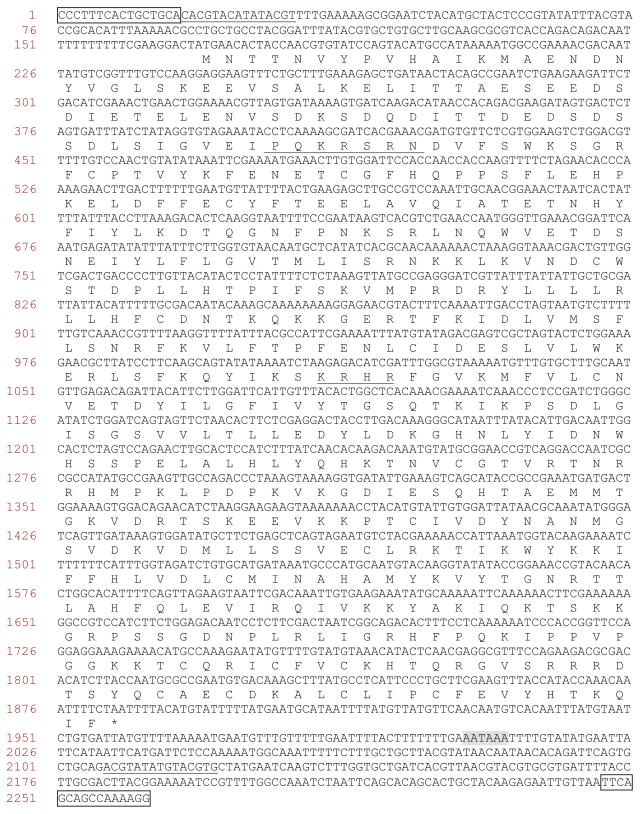

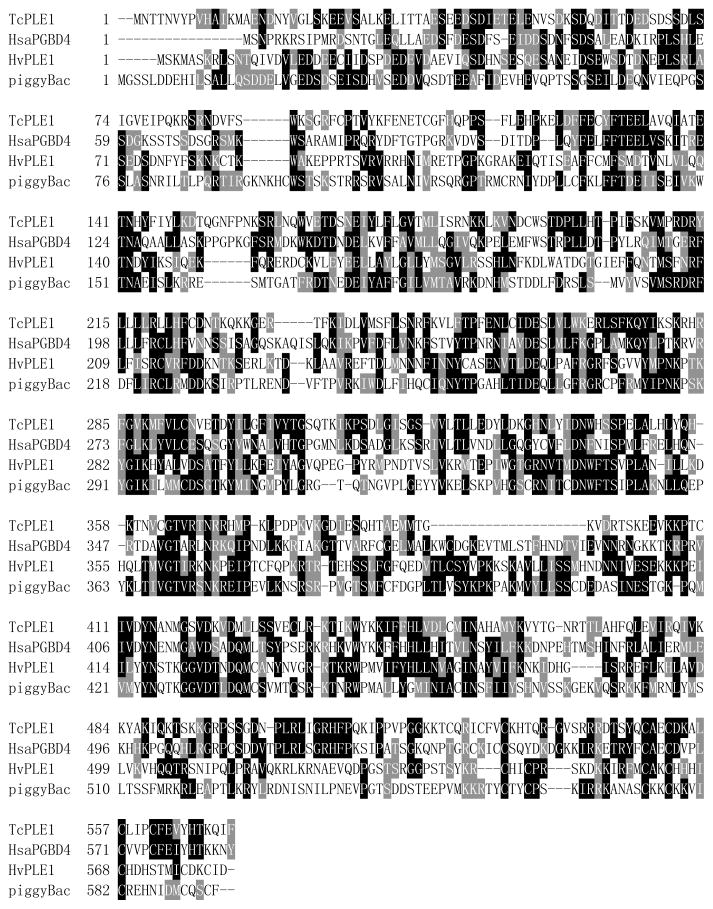

All the TcPLEs identified here, except TcPLE1, were apparently defective due to the presence of multiple stop codons and/or indels in the putative transposase encoding regions. TcPLE1 has intact 16 bp ITRs and 15 bp inverted subterminal repeats, and an ORF encoding 571 amino acid residues (Fig. 1). A potential RNA polymerase II promoter region with a high score was found in the 46 bp upstream of the ATG start codon by Neural Network Promoter Prediction (http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html). A classic polyadenylation signal sequence (AATAAA) is located 119 bp downstream of the stop codon. The PSORT webserver (http://psort.njbb.ac.jp/) predicted two bipartite nuclear localization signals in the transposase sequence (Fig. 1). Thus, TcPLE1 has retained components that are known for transposition, although there is no evidence supporting recent or current mobilization events. Among previously described PLEs in other organism, the sequence closest to TcPLE1 is that of a human PLE, HsaPGBD4 (Sarkar, 2003), with 34% amino acid identity and 60% amino acid similarity within the transposase sequence (Fig. 2). TcPLE11 and TcPLE14 are also in the same clade (Fig. 4). Two highly conserved aspartic acids, corresponding to D268 and D346 in T. ni piggyBac transposase, were also observed in TcPLE1(Fig. 2), reminiscent of the situation in several other DDE transposase domains (Sarkar et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

Nucleotide sequence and putative translation of the full-length piggyBac-like element, TcPLE1. The putative 16 bp inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) are boxed. The internal repeats are underlined. Protein translation of the transposase ORF is shown below the DNA. The amino acids in two regions encoding putative nuclear localization signals (NLS) are underlined. The canonical polyadenylation signal sequence (AATAAA) is shaded.

Figure 2.

Alignment of multiple sequences related to TcPLE1 transposase. The transposase sequences of HvPLE1 from H. virescens (GenBank Accession number ABD76335), piggyBac from T. ni (AAA87375), and HsaPGBD4 from Homo sapiens (Sarkar et al. 2003) are aligned together with TcPLE1. Identical amino acids are shown in black boxes and similar amino acids are highlighted in gray boxes.

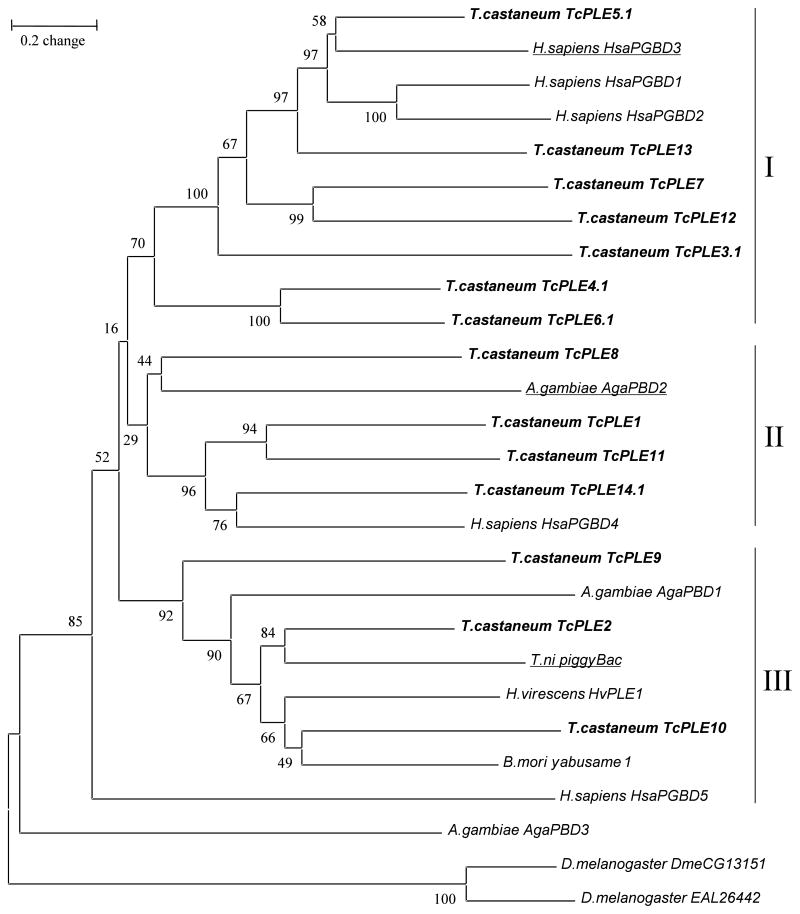

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic relationship among piggyBac-like elements based on the transposase sequences. The unrooted tree was generated in MEGA3 by the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstraps. The GenBank accession numbers for the transposase sequences encoded by yabusame-1 from B. mori and HvPLE1 from H. virescens are BAD11135 and ABD76335, respectively. Amino acid sequences without GeneBank Accession numbers were obtained from Sarkar et al. (2003).

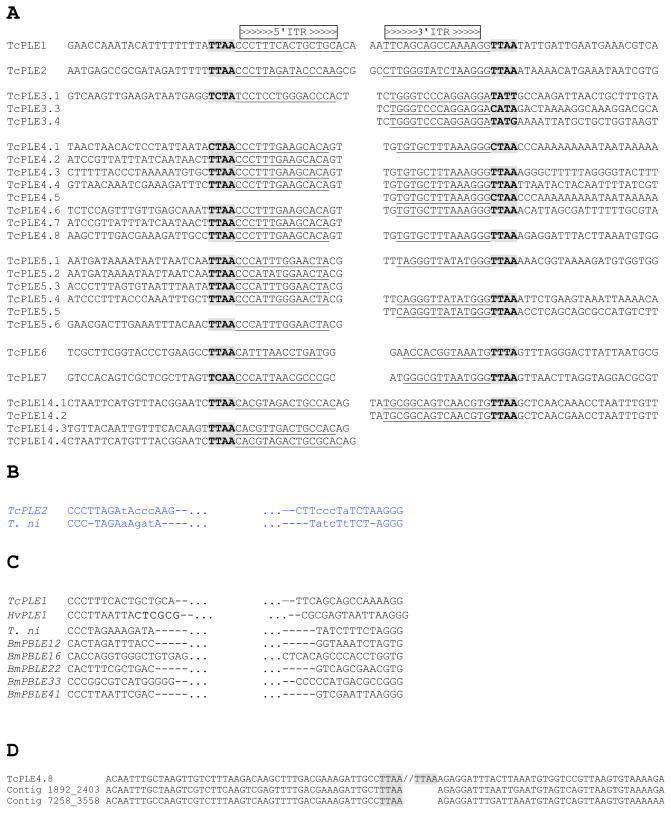

The sequence closest to the T. ni piggyBac transposase is encoded by the single copy of TcPLE2 with 38% amino acid identity and 59% amino acid similarity, respectively. However, TcPLE2 contains multiple disruptions within the putative transposase encoding region. In addition there is significant divergence between the ITR sequences of T. ni piggyBac and TcPLE2 (56% identity or only 9/16 matches when 3 gaps are introduced in the alignment) (Fig. 3A and B). Transmobilization between TcPLE2 and T. ni piggyBac, which is being used as a Tribolium transformation vector, is unlikely because of the high divergence in the ITR sequences and the disruptions of the transposase ORF in TcPLE2. Cross-inhibition of the piggyBac by the endogenous TcPLE2 is also unlikely, for which the endogenous elements utilizes RNA interference (RNAi) with the matching sequence to suppress the transcription of piggyBac transposase. For example, silencing of the Tc1 transposon by natural RNAi targeting the terminal inverted repeat was described in Caenorhabditis elegans (Sijen and Plasterk, 2003).

Figure 3.

Comparison of ITRs, and TcPLE flanking sequences. Nucleotide sequences of the inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), tetranucleotide target site, and the sequences immediately flanking TcPLEs (A). Alignment of the ITR sequences of TcPLE2 and T.ni piggyBac (B). ITR sequences of seven PLEs in addition to T. ni piggyBac, which are all found to have putative intact transposable element (C). Alignment of the sequence flanking TcPLE4.8 and two genomic sequences indicating possible insertion site polymorphism (D). The putative ITRs are underlined. The putative 4-bp target site duplications are shaded in bold font. Mismatches between ITRs of TcPLE2 and T.ni piggyBac are in lower case. The ITRs of HvPLE1 from Heliothis virescens and BmPBLE from Bombyx mori were obtained from Wang et al. (2006) and Xu et al. (2006), respectively.

3.2. Analysis of ITRs and insertion site preference of TcPLEs

We have identified a total of 20 5' ITRs and 18 3' ITRs from 25 TcPLE copies, ranging from 13 to 16 bp in length (Fig. 3A). The ITRs of piggyBac elements are characterized by two or three C/G residues at the extreme ends. Such characteristics are shared by almost all the TcPLE ITRs except the putative ITRs of TcPLE6, TcPLE14, and TcPLE3 (ATG, GTG and GGA at 3' extreme ends, respectively, instead of GGG). The ITRs of multiple copies of TcPLE3 and TcPLE4 are identical, while minor differences have occurred among the ITRs of several copies of TcPLE5 and of TcPLE14, which have likely been caused by the accumulation of point mutations over time. The divergence in ITRs among distinct types of TcPLEs may be a common phenomenon, as has been reported previously (Fig. 3A and C, Sarkar et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2006).

The typical tetranucleotide target site of PLEs (TTAA) is highly conserved in Tribolium. Slightly modified sequences flank the 5′- and/or 3′-insertion sites of several TcPLEs (Table 1, Fig. 3A), while the majority of the sequences strictly adhere to the TTAA (17/20 for the 5’ and 12/18 for the 3’ ITRs). A similar result was observed in Heliothis HvPLE1 where the TTAA is also generally conserved with minor variations (Wang et al., 2006). Whether these slightly modified target site duplications prevent subsequent excision of PLEs remains unknown. It has been reported that incorporation of an asymmetric TTAC target site at the 3' end does not prevent excision of T. ni piggyBac from the mutated end (Elick et al., 1997). We were unable to find a consensus sequence other than the TTAA in examining 25 bp immediately flanking the insertion sites. However, in this analysis two genomic sequences that are nearly identical to the genomic sequence flanking TcPLE4.8 were found that contain the conserved TTAA target site, but lack transposon insertions (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the TcPLE4.8 insertion occurred after duplication of this genomic segment.

Putative genes adjacent to TcPLE insertion sites were determined by BLASTX searches using 5 kb of sequences flanking each insertion for which 5′- and/or 3′-ITRs were identified. The BLAST search revealed an apparent preference for insertion close to transposable elements-like sequences (see Table 2). Among 20 upstream flanking sequences, seven show significant similarity to reverse transcriptase, two are similar to a gag protein, while three sequences are similar to integrase, Tc3 transposase and hAT transposase genes, respectively. Similar results were found for 18 downstream flanking sequences. Ten sequences showed significant similarity to the products of transposable elements, including reverse transcriptase and transposase.

Table 2.

Genes found in the flanking sequences of TcPLE copies in the Tribolium genome sequence (Tcas version2.0). The threshold E-value was 1e-2 in the BLASTX search.

| Name | 5' flanking sequence | 3' flanking sequence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description (gene function/organism) | GenBank Accession No. | E -value | Description (gene function/organism) | GenBank Accession No. | E- value | |

| Tc3 transposase/ Caenorhabditis elegans | P34257 | 4e-14 | No significant hit | |||

| TcPLE1 | ||||||

| TcPLE2 | reverse transcriptase/ Schistosoma mansoni | CAJ00235 | 1e-51 | reverse transcriptase / Aedes aegypti | AAZ15235 | 2e-53 |

| TcPLE3.1 | reverse transcriptase/ Aedes aegypti | AAZ15235 | 1e-54 | putative hAT transposase/ Oryza sativa | AAL86479 | 7e-09 |

| TcPLE3.3 | ND | Unknown function / Xenopus laevis | AAH92316 | 1e-14 | ||

| TcPLE3.4 | ND | No significant hit | ||||

| TcPLE4.1 | reverse transcriptase/ Trichoplusia ni | B36329 | 3e-178 | reverse transcriptase/ Trichoplusia ni | B36329 | 7e-176 |

| TcPLE4.2 | Only 362 bp available, No significant hit | ND | ||||

| TcPLE4.3 | reverse transcriptase/ Aedes aegypti | AAZ15240 | 4e-14 | No significant hit | ||

| TcPLE4.4 | Troponin C/ Aedes aegypti | EAT41816 | 7e-27 | Troponin C/ Aedes aegypti | EAT41816 | 3e-35 |

| TcPLE4.5 | ND | reverse transcriptase/ Drosophila melanogaster | AAA28508 | 6e-04 | ||

| TcPLE4.6 | Unknown function/ Xestia c-nigrum granulovirus | AAF05277 | 3e-09 | Toll interacting protein/Homo sapiens | AAH12057 | 3e-61 |

| TcPLE4.7 | MGC89587 protein/ Xenopus tropicalis | AAH76989 | 3e-46 | ND | ||

| TcPLE4.8 | putative integrase/ Oikopleura dioica | AAS21408 | 3e-28 | reverse transcriptase/ Anopheles gambiae | BAC82595 | 2e-29 |

| TcPLE5.1 | No significant hit | Only 1730 bp available, No significant hit | ||||

| TcPLE5.2 | reverse transcriptase/ Anopheles gambiae | BAC82595 | 1e-29 | ND | ||

| TcPLE5.3 | reverse transcriptase/ Bombyx mori | AAA17752 | 9e-12 | ND | ||

| TcPLE5.4 | hAT transposase/ Bactrocera dorsalis | AAL93203 | 6e-18 | gag protein/ Drosophila virilis | AAQ75091 | 7e-20 |

| TcPLE5.5 | ND | hAT transposase/ Oryza sativa | NP_918185 | 2e-10 | ||

| TcPLE5.6 | Only 1730 bp available, No significant hit | ND | ||||

| TcPLE6 | No significant hit | No significant hit | ||||

| TcPLE7 | reverse transcriptase/ Chironomus tentans | AAB04627 | 2e-27 | polyprotein/ Anopheles gambiae | CAJ14165 | 6e-21 |

| TcPLE14.1 | gag protein/ Drosophila melanogaster | AAK53387 | 5e-4 | PGBD4 transposase/ Homo sapiens | NP_689808 | 1e-10 |

| TcPLE14.2 | ND | reverse transcriptase/ Aedes aegypti | AAZ15237 | 5e-25 | ||

| TcPLE14.3 | No significant hit | ND | ||||

| TcPLE14.4 | gag protein/ Drosophila melanogaster | AAK53387 | 5e-4 | ND | ||

Only sequences flanking the identified 5′- or 3′-ITRs were analyzed. A total of 33 flanking sequences were subject to BLASTX search. Flanking sequence shorter than 5000bp are indicated. ND: Not determined.

In three cases the TcPLEs are disrupted by other TEs. TcPLE7 is disrupted by an ORF encoding 397 amino acid residues having significant similarity to a gag-like protein in a Bombyx mori retrotransposon (BAA76303). Large insertions were found in both TcPLE14.1 and TcPLE14.2, showing significant similarity to the P element. Taken together, these observations support the existence of transposition hot spots where regions of the genome tend to accumulate TEs. TEs clustered within a host genome have also reported for an oomycete and a mosquito (Ah Fong and Judelson, 2004; Tu, 2001).

3.3. Evolution of TcPLEs

Analysis of the phylogenetic relationship was made with a total of 14 transposase sequences representing each group of TcPLE, and with 13 additional PLE transposase sequences from six species, including three Lepidoptera, two Diptera and Homo sapiens as reported in Sarkar et al. (2003). The defective copies of the TcPLEs were conceptually translated with gaps introduced to maintain reading frame alignment. In the case of TcPLE9-13, the full ORF could not be predicted, and only a partial transposase sequence was used in the analysis. The different groups of TcPLEs are distributed across three major clades (Fig. 4).

The TcPLE diversity covers almost all major branches that have been described for PLEs found in the genome sequences of various organisms (Sarkar et al., 2003). Multiple different types of PLEs may be a common occurrence, as has also been observed in the Homo sapien, Anopheles gambiae, and Bombyx mori genomes, but with less divergence than in TcPLEs (Sarkar et al. 2003; Xu et al., 2006). The multiple types of TcPLEs were likely introduced into the genome of this species as independent events during evolution. In addition, ectopic recombination among homologous sequences also predicts high diversity of transposable elements in a given genome (Abrusán and Krambeck, 2006). In the case of Heliothis virescens, sequential invasions of two different PLEs were detected by comparing the rate of sequence divergence in each group (Wang et al., 2006). Unfortunately, we are unable to estimate the ages of the TcPLEs, since we could not identify the putative ancestral sequence of each TcPLE type.

The copy number of a transposable element may be maintained as a result of the balance between transposition activity of the TE and the genetic load on the host in the long term (Charlesworth and Langley, 1989). We found a range of low copy numbers (1 to 8 copies) for each TcPLE type (Table 1). It should be noted that these low numbers may not include all copies, since there are several gaps and ambiguities in the draft quality of the genome sequence. Similarly low copy numbers of each TcPLE (Table 1) were also found in other insect species. In general, the copy numbers of PLEs reported for a numbers of species, including T. ni, Bactrocera dorsalis, Heliocoverpa armigera, H. zea, Spodoptera frugiperda and H. virescens, are low to moderate, ranging from 5 to 20 copies per genome (Handler and McCombs, 2000; Zimowska and Handler, 2006; Wang et al., 2006), although the methods used to estimate copy number vary depending on the study. In contrast, for other TEs, such as the mariner-like element (MLE), the copy number varies tremendously from 2 to 17, 000 copies in different species (Hartl et al., 1997). The low copy numbers and the large diversity in the absence of extensive multiplication suggest that there may be limited activity of TcPLEs or strong selection against multiplication resulting in the rapid loss of some PLE copies throughout a long evolutionary timescale.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation and the State Key Basic Research Project of China under grant no. 30671375 and 2006CB102002, respectively. The work of SWang and SBrown is supported by NIH Grant number P20RR016475 from the INBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources.

References

- Ah Fong A, Judelson HS. The hAT-like DNA transposon, DodoPi, resides in a cluster of retro- and DNA transposons in the stramenopile Phytophthora infestans. Mol Genet Genomics. 2004;271:577–585. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen ML, Handler AM, Berkebile DR, Skoda SR. piggyBac transformation of the New World screwworm, Cochliomyia hominivorax, produces multiple distinct mutant strains. Med Vet Entomol. 2004;18:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2004.0473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrusán G, Krambeck HJ. Competition may determine the diversity of transposable elements. Theor Popul Biol. 2006;70:364–375. doi: 10.1016/j.tpb.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghammer AJ, Klingler M, Wimmer EA. A universal marker for transgenic insects. Nature. 1999;402:370–371. doi: 10.1038/46463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braam LAM, Reznikoff WS. Functional characterization of the Tn5 transposase by limited proteolysis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10908–10913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary LC, Goebel M, Corsaro HH, Wang HH, Rosen E, Fraser MJ. Transposon mutagenesis of baculoviruses: analysis of Trichoplusia ni transposon IFP2 inserions within the FP-Locus of nuclear polyhedrosis viruses. Virology. 1989;161:8–17. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B, Langley CH. The population genetics of Drosophila transposable elements. Annu Rev Genet. 1989;23:251–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.23.120189.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding S, Wu X, Li G, Han M, Zhuang Y, Xu T. Efficient transposition of the piggyBac (PB) transposon in mammalian cells and mice. Cell. 2005;122:473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elick TA, Lobo N, Fraser MJ. Analysis of the cis-acting DNA elements required for piggyBac transposable element excision. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;255:605–610. doi: 10.1007/s004380050534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser MJ. The TTAA-specific family of transposable elements. Identification, Functional Characterization, and Utility for Transformation of Insects. In: Handler M, James AA, editors. Insect Transgenesis: Methods and Applications. CRC Press; Baton Rouge: 2000. pp. 249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser MJ, Smith GE, Summers MD. Acquisition of host-cell DNA-sequences by baculoviruses—relationship between host DNA insertions and FP mutants of Autographa-californica and Galleria-mellonella nuclear polyhedrosis viruses. J Virol. 1983;47:287–300. doi: 10.1128/jvi.47.2.287-300.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handler AM. Use of the piggyBac transposon for germline transformation of insects. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;32:1211–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(02)00084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handler AM, McCombs SD. The piggyBac transposon mediates germ-line transformation in the Oriental fruit fly and closely related elements exist in its genome. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9:605–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl DL, Lohe AR, Lozovskaya ER. Modern thoughts on an ancient mariner: function, evolution, regulation. Annu Rev Genet. 1997;31:337–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.31.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Briefings Bioinformatics. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen MD, Berghammer AJ, Brown SJ, Denell RE, Klingler M, Beeman RW. Piggybac-Mediated Germline Transformation in the Beetle Tribolium castaneum. Insect Mol Biol. 2003;12:433–440. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen MD, Kimzey T, Shippy TD, Brown SJ, Denell RE, Beeman RW. piggyBac-based insertional mutagenesis in Tribolium castaneum using donor/helper hybrids. Insect Mol Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00727.x. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlopoulos A, Berghammer A, Averof M, Klingler M. Efficient transformation of the beetle Tribolium castaneum using the Minos transposable element: quantitative and qualitative analysis of genomic integration events. Genetics. 2004;167:737–746. doi: 10.1534/genetics.103.023085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AS, Franz G, Atkinson PW. Insect transgenesis and its potential role in agriculture and human health. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Sim C, Hong YS, Hogan JR, Fraser MJ, Robertson HM, Collins FH. Molecular evolutionary analysis of the widespread piggyBac transposon family and related "domesticated" sequences. Mol Genet Genomics. 2003;270:173–180. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0909-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijen T, Plasterk RH. Transposon silencing in the Caenorhabditis elegans germ line by natural RNAi. Nature. 2003;426:310–314. doi: 10.1038/nature02107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinmyo Y, Mito T, Matsushita T, Sarashina I, Miyawaki K, Ohuchi H, Noji S. piggyBac-mediated somatic transformation of the two-spotted cricket, Gryllus bimaculatus. Dev Growth Differ. 2004;46:343–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169x.2004.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumitani M, Yamamoto DS, Oishi K, Lee JM, Hatakeyama M. Germline transformation of the sawfly, Athalia rosae (Hymenoptera: Symphyta), mediated by a piggyBac-derived vector. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33:449–458. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(03)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan P, Atkinson PW, O’Brochta DA. Transposable element interactions in insects: crossmobilization of hobo and Hermes. Insect Mol Biol. 1999;8:359–368. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.83128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgs DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties, and weight matrix choice. Nucl Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z. Eight novel families of miniature inverted repeat transposable elements in the African malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1699–1704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041593198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ren X, Miller TA, Park Y. piggyBac-like elements PLE in the tobacco budworm, Heliothis virescens (Fabricius) Insect Mol Biol. 2006;15:435–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu HF, Xia QY, Liu C, Cheng TC, Zhao P, Duan J, Zha XF, Liu SP. Identification and characterization of piggyBac-like elements in the genome of domesticated silkworm, Bombyx mori. Mol Genet Genomics. 2006;276:31–40. doi: 10.1007/s00438-006-0124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimowska GJ, Handler AM. Highly Conserved piggybac Elements in Noctuid Species of Lepidoptera. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;36:421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.