Abstract

The physiological responses and transcription profiling of Pichia pastoris GS115 to simulated microgravity (SMG) were substantially changed compared with normal gravity (NG) control. We previously reported that the recombinant P. pastoris grew faster under SMG than NG during methanol induction phase and the efficiencies of recombinant enzyme production and secretion were enhanced under SMG, which was considered as the consequence of changed transcriptional levels of some key genes. In this work, transcriptiome profiling of P. pastoris cultured under SMG and NG conditions at exponential and stationary phases were determined using next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. Four categories of 141 genes function as methanol utilization, protein chaperone, RNA polymerase and protein transportation or secretion classified according to Gene Ontology (GO) were chosen to be analyzed on the basis of NGS results. And 80 significantly changed genes were weighted and estimated by Cluster 3.0. It was found that most genes of methanol metabolism (85% of 20 genes) and protein transportation or secretion (82.2% of 45 genes) were significantly up-regulated under SMG. Furthermore the quantity and fold change of up-regulated genes in exponential phase of each category were higher than those of stationary phase. The results indicate that the up-regulated genes of methanol metabolism and protein transportation or secretion mainly contribute to enhanced production and secretion of the recombinant protein under SMG.

Introduction

Microgravity has significant effects on numerous microbial characteristics [1]. And studies concerning the influences of microgravity on microbial cells are drawing much attention because such information will lead to the advancement of knowledge and application about space biotechnology [2]. However, SMG was more applicable and feasible to most researchers due to much lower cost, without any further need of spaceflight and extreme sensitive instrumentations, which definitely make the experiments out of range for future projects. Therefore a series of ground-based suspension culture bioreactors which could model various aspects of spaceflight were invented [1]. One such bioreactor named as high-aspect-ratio vessel (HARV, Synthecon) [3] was used in this study. The HARV employed for cell suspension culture and tissue growth permits cell growth in suspension and minimizes the fluid shear levels encountered by cells [1], [4]. When the cell culture vessel rotates, microbial cells do not settle down but revolve around a horizontal axis and continuously fall through the fluid at 1×g terminal velocity condition, which lead to 1∼2×10−2 gravity environment [5]. Exchange of dissolved gas has been achieved through a permeable membrane at the back of this vessel.

There were several studies that had demonstrated that microbial cellular processes, such as cell growth, gene expression [6], metabolism [7], and secondary-metabolites production [8], [9] changed when microbial cells were cultured under microgravity or SMG conditions compared with NG. In fact, most of these studies concerning about the effects of microgravity or SMG on the functions of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells remained focus on the safety and health of astronauts during a long spaceflight time [10], especially supported by NASA. However, we are interested in application of simulated microgravity techniques in biochemical engineering such as recombinant protein production by microbial host and the mechanisms that microbes sense and respond to the environment of SMG.

β-glucuronidase is an important enzyme from Penicillium purpurogenum Stoll (CGMCC 3. 3708) that can directly hydrolyze glycyrrhizin (GL) to glycyrrhetinic acid monoglucuronide (GAMG) [11]. GAMG is useful in clinical treatment of many inflammatory diseases and much safer, more effective and absorbable than GL [12]. In this study P. pastoris is utilized as a host for production of PGUS gene (GenBank Accession No. EU095019) because its expression system presents many advantages [13]. Besides its high-level expression of recombinant proteins, P. pastoris is also well-known for its strong but tightly regulated alcohol oxidase-1 (AOX1) gene promoter [14]. We previously transformed PGUS gene using the vector pPIC9K into P. pastoris GS115 cells and reported that the recombinant P. pastoris grew faster under SMG than NG during methanol induction phase and the efficiencies of recombinant PGUS production and secretion were enhanced under SMG as compared with NG control [15]. We hypothesized that the important reason that caused better growth and enhancement of PGUS expression was due to changed transcriptional levels of some key genes, namely SMG condition possibly could regulate molecular responses of the microbial cells. Hence, we examined the transcriptome profiling of the recombinant P. pastoris by using NGS as it provides cost-effective, rapid and highly parallel sequencing of large numbers of DNA fragments from complex samples or transcriptomes for gene expression profiling and functional genomics research [16]. Thus we are able to identify transcriptional factors and signaling pathways involved in this special response by figuring out the regulatory motifs of transcriptional profiling of genes, such as, the genes functioned as carbohydrate metabolism, protein synthesis, protein transportation or secretion.

Materials and Methods

Strain and Plasmid

The recombinant strain Pichia pastoris GS115 used in this study was constructed and preserved in our previous research work [15]. Expression of pgus gene was under the control of alcohol oxidase-1 gene promoter for the production of recombinant protein. Standard procedure was adopted for the recombinant pgus gene manipulations [17]. The recombinant P. pastoris clones with the highest resistance to G418 were used for HARV cultivation.

Growth conditions

A single colony of recombinant P. pastoris clone isolated from the YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose, and 2% agar) plate was used to inoculate 200 ml of BMGY medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 100 mmol l−1 phosphate buffer saline, pH 6.0, 1.34% YNB, 1.61 µmol l−1 biotin, 0.004% histidine, 1% glycerol) in a 500 ml shaker flask and incubated at 30°C and 220 rpm for 8 h to OD600 = 2–3. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 10 min, washed twice with phosphate buffer and resuspended in 100 ml BMMY medium (1% methanol instead of glycerol as the sole carbon source). Then aliquots of the cultures were loaded into two HARV vessels used in this work that were completely filled with 50 mL BMMY culture medium for SMG and NG cultures, respectively. All bubbles were removed to reduce shear using sterile disposable syringe. Methanol was added after every 24 h to a final concentration of 1%. We performed continuous dilutions after every 8 h of induction to guarantee all the cells maintaining in the mid-exponential growth phase by monitoring the optical density. After four repeated processes (16 generations), the culture medium was sampled and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, then pellets were washed, frozen and stored at −80°C for further RNA isolation. To obtain the cells in stationary phase, four repeated 16 h of the same induction processes (32 generations) were carried out.

RNA isolation and Samples preparation

Total RNA was isolated using RNA Purification Kit (Amresco Inc, Cochran Road, Solon, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA pellets were washed with cold 70% ethanol, air dried, and then resuspended in 30 µL distilled water pretreated with diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC). Then the extracted RNA were incubated for 60 min at 42°C with 2 µL DNase I (5 U/µL) and 0.5 µL RNase Inhibitor (40 U/µL) (Takara, Dalian, China) to remove residual genomic DNA. After that phenol-chloroform-isopentanol was utilized to dissolve and remove DNase I and RNase Inhibitor. 28 s/18 s rRNA band intensity was determined using Agilent 2100 (Agilent Technologies, US) and the readings of extracted RNA samples between 1.5 and 2 were selected for library construction and sequencing.

Library preparation and NGS sequencing

We performed the direct sequencing on the Illumina platform with the modified protocol [18]. 6 µg total RNA from exponential and stationary growth phases under SMG and NG conditions captured by magnetic oligo (dT) beads was used for cDNA synthesis. Double stranded bead-bound cDNA was digested with the anchoring enzyme NlaIII. Then the 3′-cDNA fragments were linked to the adapter 1 that included the recognition site of enzyme NlaIII (5′-CATG-3′). Tag fragments with adapter 1 were isolated from the recognition site. After that the adapter 2 (5′-linker, containing a recognition site of MmeI) was added to the site of MmeI digestion. Subsequently all the adapter-ligated cDNA tags were amplified. Each library was then sequenced on an individual lane on an Illumina Genome Analyzer II for 36 cycles. One sample from each time point under SMG and NG was sequenced for a second time with 32 cycles.

Data analysis and hierarchical clustering

The magnitude of gene transcriptional profiling and abundance of a particular transcript relative to controls in a certain sample are the most desired information. We can obtain the fold change of transcriptional level of a single gene under SMG compared with NG condition using NGS assay, while hierarchical clustering map can give more intuitive result. Hierarchical clustering of the NGS data was performed as previously described [19] using the software Cluster 3.0 (http://bonsai.hgc.jp/~mdehoon/software/cluster). The samples of RNA were obtained from exponential or stationary phases under SMG and NG conditions, respectively. The NGS data of four categories that each comprised of 20 genes related to metabolism and protein synthesis or transportation were clustered. The data from each experiment was weighted and estimated by Cluster 3.0 according to the similarity of expression profiling of each gene to others. The results of cluster were displayed using the software Java TreeView (http://jtreeview.sourceforge.net).

RT-qPCR analysis

Total RNA (about 0.05 µg) was isolated from P. pastoris cultured under SMG and NG conditions and reverse transcribed using a two-step strategy described previously [20] with reverse transcriptase PCR kit (Fermentas). The housekeeping genes (GAPDH) were selected for normalizing expression of the samples. All real-time PCR reactions were performed on the M×3000P (Agilent Technologies, US) with fluorescence signal detection (SYBR Green) after each amplification cycle. Each PCR reaction was performed in a 25.0 µl reaction mixture containing 12.5 µl of 2×SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa), 2.0 µl of properly diluted cDNA from 20–30 ng/ml of cDNA for all genes used for RT-qPCR, 0.5 µl of 50×ROX reference dye II (for error correction between wells), 0.5 µl of each primer at 10 µM and 9 µl of sterile distilled water. The negative controls (without cDNA) for each primer set were included in each cycle. The thermal cycling conditions included initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles each of denaturation (5 s at 95°C), annealing (20 s at 64°C) and extension (30 s at 72°C with a single fluorescence measurement), and a melt curve program with continuous fluorescence measurement. The data from the real-time PCR was converted to  (

( ) that represents fold change, where C

T represents the threshold cycle [21], [22]. All the values were determined through triplicate experiments for subsequent analysis. Statistical significance was considered significant at P<0.05.

) that represents fold change, where C

T represents the threshold cycle [21], [22]. All the values were determined through triplicate experiments for subsequent analysis. Statistical significance was considered significant at P<0.05.

Results

Library composition and sequencing of the RNA transcriptomes

The RNA transcriptomes of P. pastoris GS115 cultured under SMG and NG conditions were analyzed by NGS using Solexa Genome Analyzer. Library composition was achieved by mapping all short reads longer than 12 nt. About 80% of the sequences were available to map and the comparative extreme long reads, for example above 40 nt, were less than 3%. To investigate the reproducibility of the analysis, two samples derived from either exponential or stationary phase under SMG and NG conditions were sequenced in duplicate ( Table 1 ). The low quality tags were filtered and a total of 3716288, 3262032, 3149116, and 5077915 clean tags were obtained. 14514, 10938, 15143, and 10366 distinct tags that matched to unique genes were 25.75%, 24.55%, 17.55%, and 20.95% of total tags, which determined each sequence annotation and expression profiling. In addition, there were over 65% and 50% of the distinct tags available between 2–10 copies, about 15% and 25% of the distinct tags between 11–50 copies, and less than 10% of the tags had more than 51 copies derived from SMG and NG conditions, respectively. Sequencing saturation analysis that was used for estimating the transcriptome coverage for the four data sets was carried out subsequently (Fig. S1). It can be concluded that 60%–80% of all the genes have been identified when the number of the sequencing tags was saturated (detected tags reached to 7–10×105).

Table 1. Sequencing quality evaluation of the cDNA samples of P. pastoris GS115 cultured under SMG and NG conditions.

| Tags sequenced | Stationary (SMG) | Stationary (NG) | Exponential (SMG) | Exponential (NG) | |

| Number of total tags | Total tags | 3748512 | 3932994 | 3748455 | 5200265 |

| Distinct tags | 87368 | 61891 | 87367 | 82681 | |

| Number of clean tags | Total tags | 3716288 | 3262032 | 3149116 | 5077915 |

| Distinct tags | 76356 | 70016 | 106337 | 85159 | |

| Number of tags matched to gene | Total tags | 568040 | 800087 | 568043 | 450031 |

| Distribution of total tags | 15.28% | 24.53% | 15.16% | 10.06% | |

| Distinct tags | 12058 | 18082 | 16894 | 10998 | |

| Distribution of distinct tags | 12.22% | 18.65% | 15.95% | 10.04% | |

| Number of tags matched to unique gene | Total tags | 1986486 | 1446734 | 1987115 | 659187 |

| Distribution of total tags | 53.45% | 44.36% | 52.32% | 12.98% | |

| Distinct tags | 14514 | 10938 | 15143 | 10366 | |

| Distribution of distinct tags | 25.75% | 24.55% | 17.55% | 20.95% | |

| Number of unknown tags | Total tags | 648151 | 571776 | 665218 | 731177 |

| Distribution of total tags | 17.44% | 17.53% | 17.76% | 22.76% | |

| Distinct tags | 30512 | 23829 | 47579 | 25104 | |

| Distribution of distinct tags | 54.14% | 59.78% | 55.14% | 55.55% |

Expression profiling of the four categories of genes

We considered the important reason that led to enhancement of the PGUS expression is probably due to alteration of transcriptional levels of certain kinds of genes which have influences in the recombinant protein expression and transportation. Four categories of genes identified according to Gene Ontology (GO), such as methanol utilization, protein chaperone, RNA polymerase and protein secretion or transportation, were chosen to be analyzed from the data of transcriptome profiling using NGS. The abundance of the filtered genes in the data set has been examined according to the number of transcripts per million (TPM) of distinct clean tags from the NGS results. In order to avoid the gene expression changes caused by the response to growth phases, we performed expression analysis of P. pastoris GS115 cultured under SMG and NG conditions at exponential and stationary phases. The false discovery rates (FDR)<0.001 and the value of |log2ratio|≧1 were used as determining the statistical significance of genes expression. Among 4120 normalized and filtered genes, 2705 genes were changed when the recombinant P. pastoris responded to the environment of SMG.

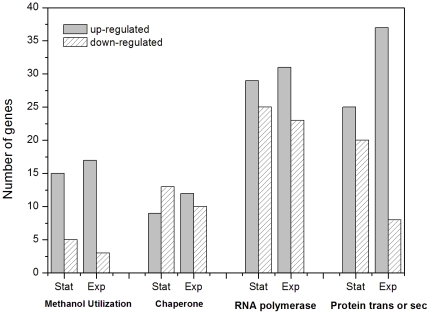

141 genes that function as methanol metabolism, chaperone, RNA polymerase, and protein transportation or secretion classified using GO resource had significant different responses under SMG condition compared with NG control in HARV ( Table 2 and Table S1, S2). In these four categories of target genes, 78 were up-regulated and 63 were down-regulated in stationary phase, while 97 up-regulated and 44 down-regulated in exponential phase. The transcriptional level changed notably between genes in these four categories; for example, the gene that functions as essential protein possibly involved in secretion (PAS_chr3_0292) was up-regulated 8.3 folds in exponential phase and this level was higher than any other genes while the lowest down-regulated gene (PAS_chr1-1_0237) identified as protein chaperone was 6.1 folds. Figure 1 shows the numbers of significant genes in each category. The transcriptional profiling of each category was similar in the two growth phases. It is interesting to find that the numbers of up-regulated genes related to methanol metabolism (85% of 20 genes) and protein transportation or secretion (82.2% of 45 genes) were about 5 times more than those of down-regulated genes in exponential phase. However, the rest of other two categories had almost no significant differences in the two phases. Furthermore the quantity and fold change of up-regulated genes in exponential phase of each category were higher than that of stationary phase especially the categories of methanol metabolism and protein transportation or secretion.

Table 2. Expression patterns of chaperone and protein transportation or secretion genes among the four categories related to protein expression studied in this work during growth under SMG compared with NG control in HARV.

| Gene | Gene ID | Fold Change of expression levelsa | Functional Description | |||

| Stationary Phase | Exponential Phase | |||||

| Up | Down | Up | Down | |||

| Protein Chaperone | ||||||

| PAS_chr3_0480 | 8199608 | 3.5 | 4.1 | Putative chaperone | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0323 | 8199011 | 1.5 | 1.4 | Essential Hsp90p co-chaperone | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0421 | 8198889 | 1.4 | 3.2 | Protein chaperone or co-chaperone in ER | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0140 | 8198455 | 1.3 | 2.2 | Chaperone involved in protein folding | ||

| PAS_chr2-2_0066 | 8199171 | 2.2 | 2.0 | Protein chaperone regulator | ||

| PAS_chr2-2_0092 | 8199196 | 2.1 | 1.8 | Putative chaperone | ||

| PAS_chr4_0051 | 8201142 | 1.0 | 1.8 | Hsp40p co-chaperone | ||

| PAS_chr2-2_0323 | 8198223 | 1.1 | 1.7 | Hsp70 Ssc1p co-chaperone | ||

| PAS_chr1-4_0072 | 8197289 | 3.7 | 1.5 | Co-chaperone and ATPase activator | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0518 | 8198440 | 1.6 | 1.2 | Hsp90p co-chaperone | ||

| PAS_chr3_0731 | 8200426 | 1.5 | 1.1 | Ribosome-associated molecular chaperone | ||

| PAS_chr1-4_0130 | 8197345 | 1.1 | 1.5 | Heat shock protein Hsp90 | ||

| PAS_chr1-3_0063 | 8197373 | 1.5 | 2.0 | ER chaperone | ||

| PAS_chr1-3_0116 | 8197585 | 1.4 | 1.1 | ER packaging chaperone | ||

| PAS_chr2-2_0151 | 8198728 | 1.4 | 1.5 | Type II Hsp40p co-chaperone | ||

| PAS_chr2-2_0015 | 8198974 | 1.2 | 1.4 | Putative chaperone DnaJ | ||

| PAS_chr1-1_0237 | 8196739 | 4.9 | 6.1 | Nucleotide exchange factor of the chaperon Kar2p | ||

| PAS_chr1-4_0519 | 8197103 | 1.9 | 2.5 | Co-chaperone that stimulates the ATPase Ssa1p | ||

| PAS_chr1-3_0137 | 8197605 | 1.7 | 1.9 | Molecular chaperone | ||

| PAS_chr3_0571 | 8199935 | 1.3 | 2.0 | Subunit of the chaperonin Cct ring complex | ||

| PAS_chr4_0290 | 8200732 | 1.4 | 2.2 | Vacuolar transporter chaperon | ||

| PAS_chr1-3_0102 | 8197412 | 1.2 | 1.6 | Chaperon in ER | ||

| Protein Transportation or Secretion | ||||||

| PAS_chr3_0292 | 8200207 | 3.0 | 8.3 | Essential protein possibly involved in secretion | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0342 | 8199030 | 2.7 | 4.2 | Secretion promoter | ||

| PAS_chr4_0868 | 8201266 | 1.3 | 6.7 | ER to Golgi transporter | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0484 | 8198407 | 1.5 | 2.5 | Putative ER to Golgi transporter | ||

| PAS_chr1-1_0187 | 8197921 | 1.2 | 2.5 | Dynein-related ATPase | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0744 | 8198362 | 1.9 | 1.6 | Microtubule motor protein | ||

| PAS_chr4_0900 | 8201304 | 1.9 | 6.8 | Kinesin-like protein | ||

| PAS_chr4_0618 | 8201327 | 1.8 | 3.2 | Type I myosin | ||

| PAS_chr1-4_0271 | 8196942 | 1.9 | 5.9 | MAKK in protein kinase C signaling pathway | ||

| PAS_FragD_0005 | 8200509 | 1.7 | 3.7 | Vacuolar protein sorting factor | ||

| PAS_chr3_0143 | 8199422 | 2.5 | 6.3 | Rab GTPase essential for exocytosis | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0074 | 8198470 | 1.6 | 2.0 | Protein exocytosis regulator | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0056 | 8198175 | 1.5 | 1.2 | Palmitoyltransferase that acts on the SNAREs | ||

| PAS_chr1-3_0202 | 8196437 | 1.3 | 2.2 | Essential subunit of Sec61 complex | ||

| PAS_chr2-2_0210 | 8198618 | 1.8 | 3.4 | β-subunit of the Sec61p ER translocation complex | ||

| PAS_chr1-4_0294 | 8197744 | 1.6 | 1.1 | Secretory vesicles locator | ||

| PAS_chr1-4_0231 | 8196905 | 2.8 | 2.2 | Essential component of the COPII coat of secretory pathway vesicles | ||

| PAS_chr4_0165 | 8201075 | 2.9 | 3.4 | GTPase involved in the protein secretory pathway | ||

| PAS_chr3_0347 | 8199480 | 6.6 | 6.7 | Exocytosis regulator | ||

| PAS_chr4_0078 | 8201165 | 2.9 | 2.5 | Essential protein involved in splicesome assembly and exocytosis | ||

| PAS_chr1-4_0452 | 8197040 | 1.7 | 1.3 | Essential subunit of exocyst complex | ||

| PAS_chr4_0695 | 8200591 | 1.6 | 3.0 | Essential subunit of exocyst complex | ||

| PAS_chr4_0134 | 8201046 | 1.1 | 2.1 | Exocytosis regulator | ||

| PAS_chr1-4_0066 | 8197283 | 1.2 | 1.8 | Effector of Sec4p to form complex with Sec4p and t-SNARE | ||

| PAS_chr4_0704 | 8200600 | 1.1 | 2.4 | A component of autophagosomes and Cvt vesicles | ||

| PAS_chr4_0098 | 8201184 | 1.9 | 2.3 | Subunit of elongator complex | ||

| PAS_chr3_0974 | 8199721 | 2.0 | 2.1 | ER-Golgi protein transport | ||

| PAS_chr1-4_0629 | 8197837 | 2.7 | 1.7 | Subunit of the Ssh1 translocon complex | ||

| PAS_chr3_0342 | 8199475 | 1.5 | 1.6 | ATPase required for the release of Sec17p | ||

| PAS_chr4_0284 | 8200501 | 1.8 | 2.0 | Cytoplasmic thioredoxin isoenzyme | ||

| PAS_chr3_1107 | 8199694 | 1.9 | 1.8 | Protein required for fusion of cvt-vesicles | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0199 | 8198581 | 1.6 | 1.8 | Putative protein transport | ||

| PAS_chr3_0042 | 8199328 | 1.4 | 2.1 | Protein kinase involved in vacuolar protein sorting | ||

| PAS_chr4_0062 | 8201150 | 1.2 | 2.8 | Vacuolar membrane protein | ||

| PAS_chr1-4_0528 | 8197112 | 1.2 | 2.1 | GTPase of the Ypt/Rab family | ||

| PAS_chr4_0395 | 8200679 | 2.1 | 1.9 | Essential subunit of Sec63 complex | ||

| PAS_chr4_0391 | 8200675 | 1.8 | 2.0 | Component of the translocase of outer membrane complex | ||

| PAS_chr2-2_0316 | 8198216 | 2.1 | 2.2 | Golgi to plasma membrane protein transport | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0572 | 8198010 | 1.7 | 1.9 | Protein transport regulator | ||

| PAS_chr1-4_0555 | 8197686 | 1.5 | 1.2 | Adapter protein for Cvt pathway | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0625 | 8198939 | 1.5 | 2.0 | Type I transmembrane sorting receptor | ||

| PAS_chr3_0586 | 8199790 | 1.6 | 2.8 | Rab escort protein | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0644 | 8199258 | 1.6 | 1.4 | Protein required for vesicular transport between ER and Golgi | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0380 | 8199068 | 1.4 | 2.5 | Protein involved in nuclear export of the large ribosomal subunit | ||

| PAS_chr2-1_0641 | 8199255 | 2.1 | 1.2 | Protein required for vesicle formation in autophagy | ||

Fold change of expression levels = log2 Ratio(SMG/NG).

Figure 1. 141 significant genes classified using GO resource.

These genes functioned as methanol metabolism, chaperone, RNA polymerase, and protein transportation or secretion in P. pastoris GS115 differentially responded to SMG condition.

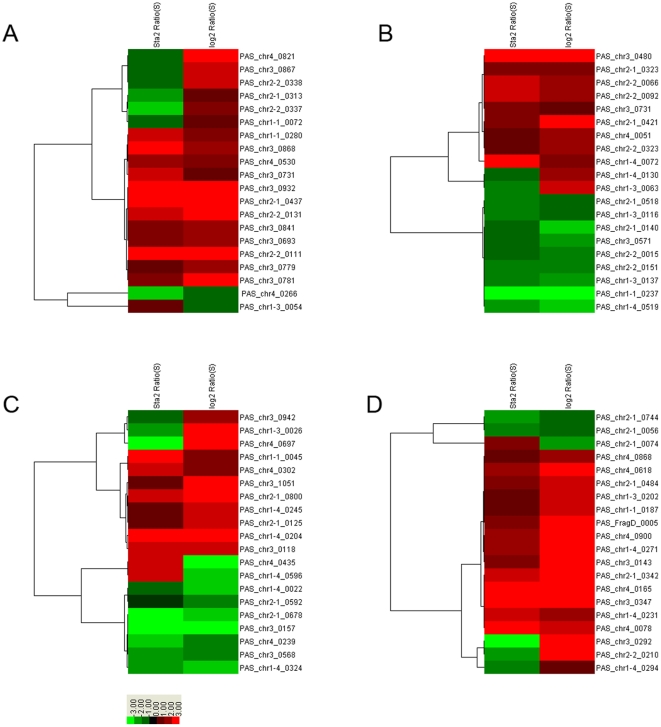

Hierarchical clustering analysis

80 most differentially expressed genes with at least 1.5 fold changes in four categories (20 genes per category) were clustered by average linkage using Cluster 3.0. A two-dimensional hierarchical cluster heat map showed the overall transcriptional response of the P. pastoris GS115 cells cultured under SMG and NG environments in HARVs ( Fig. 2 ). Gene ID was given to the right of the colored image and the corresponding source of the growth phases were shown at the top of the bands. The red and green bands that denoted to up-regulated and down-regulated, respectively represent fold change of expression level of each gene under SMG compared with NG. Similar as Table 2 and Table S1, S2, most genes related to methanol metabolism and protein secretion were up-regulated in both growth phases. And the degree of changes of these two categories was significantly higher than genes related to protein chaperone and RNA polymerase.

Figure 2. Hierarchical cluster analysis of the expression profile of four functional categories of genes under SMG and NG.

(A) methanol utilization; (B) protein chaperone; (C) RNA polymerase and (D) protein secretion or transportation. The bottom color bar represents the expression level of each gene, which red and green denote to up-regulated and down-regulated, respectively. Log2 Ratio and sta2 Ratio represent the cDNA samples were achieved from exponential or stationary phases, respectively.

Real time PCR analysis

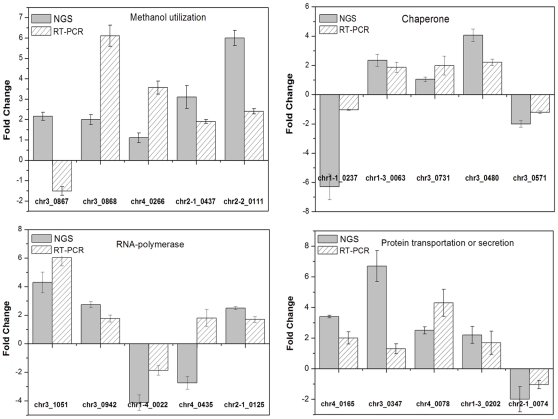

We compared the NGS expression levels with real time quantitative PCR for further verification of the NGS results. Five genes in each category were selected at random for quantitative real time PCR analysis ( Fig. 3 ). Although minor variation of transcriptional levels appeared between the two analyses, most of the tested 20 genes (18/20) matched well in the expression fold change and directions (up- and down-regulated). However two genes (PAS_chr3_0867 and PAS_chr4_0435) show different results between NGS and real time PCR data sets.

Figure 3. Comparison results of NGS and real time RT-PCR.

Expression profiling of 20 genes chosen from four different functional categories according to the cluster analysis were examined using real time RT-PCR. The cDNA samples used in this comparison were extracted from exponential phase.

Discussion

Simulated microgravity that had been considered as an extreme and special environment presents many novel aspects to study microorganisms. And studies concerning the influence of SMG on microbial cells are receiving much attention. The changed physiology and metabolism of microbes, such as shortened lag phase, increase in growth rate and higher final cell counts, would happen in the low shear fluid environment of SMG [23], [24]. We previously reported that growth of P. pastoris GS115 accelerated and the efficiencies of the recombinant PGUS production and secretion were enhanced under SMG compared with NG control. It is considered that the important reason that causes faster growth and enhancement of PGUS expression may be related to altered genes transcription. However the molecular mechanisms by which the culture conditions of SMG in the HARV modulated gene expression in P. pastoris remained unknown.

In order to find the mechanism of enhanced PGUS production under SMG environment, transcriptional levels of the recombinant P. pastoris GS115 cultured in exponential and stationary phases were determined using NGS on the Illumina platform. All the distinct tag-mapped genes were identified in each library and the tendency of sequenced tags indicated that saturated numbers of matched genes is obtained. Although part of the filtered tags can not match the correct sequence of P. pastoris GS115 genome, these “mismatched” tags have no influence on the construction of each library since they probably represent the novel genes to be identified. There are still a large proportion of unique distinct tags enough for library construction. For the changed growth and recombinant protein expression, we summarized the transcriptional profiling of four categories of genes that were related to metabolism and protein expression such as methanol utilization, protein chaperone, RNA polymerase and protein secretion or transportation. Then we applied the cluster to four sets of NGS data including significant 80 genes (20 genes of each category) and the hierarchical cluster map gave more intuitive comparison.

For the four categories of genes, the quantity and fold change of up-regulated genes in exponential phase of each category were higher than stationary phase, because the whole process of protein synthesis, folding, transportation or secretion is more active at exponential phase of the cells. Among the significant changed 141 genes, most genes related to methanol metabolism and protein transportation or secretion had been up-regulated in both growth phases. P. pastoris GS115 cells were cultured under the same conditions of the first stage in which glycerol was used as sole carbon source and there was only one difference (SMG and NG) in the second stage of induction in which methanol was used as the sole carbon resource instead of glycerol. The up-regulated methanol metabolism genes directly led to more efficient utilization of the only carbon source and ultimately more final cell counts were achieved. The alcohol oxidase gene (PAS_chr4_0821) that was the major source of methanol-oxidizing activity in methanol-grown P. pastoris had been up-regulated 3.6 folds in exponential phase under SMG. In fact, alcohol oxidase gene has been proved to be a strong but tightly regulated promoter [14]. Thus the significant change of this gene would cause faster oxygen and methanol uptake, which promoted transcription of the recombinant gene. As well as alcohol oxidase gene, several key genes coding for the respective enzymes involved in methanol metabolism pathway in P. pastoris, for example, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (PAS_chr2-2_0111), NAD(+)-dependent formate dehydrogenase (PAS_chr3_0932) and catalase A (PAS_chr2-2_0131), were highly up-regulated for 6.0, 4.0 and 2.4 folds in exponential phase, respectively. Furthermore, the transcriptional levels of these genes were all up-regulated for 2.8 folds at least in stationary phase. Due to the optimized laminar flow condition and the minimized mechanical stresses of SMG [5], the results also indicated that the unique environment of SMG could significantly strengthen the transcriptional responses of P. pastoris in methanol utilization and metabolism at the induction stage.

Interestingly, genes functioned as protein transportation or secretion were found also highly up-regulated. And even transcriptional levels of the down-regulated genes were comparative lower than other categories. It is likely that these up-regulated genes also contribute to enhance production of the recombinant protein under SMG environment. Demain et al had reported that in most cases secretion of secondary metabolites was inhibited under SMG [8]. The environment around the cell cultured under SMG turns to be a special zone with less nutrition but high concentration of metabolites [23], which probably cause reduced secretion of secondary metabolites. However it was concluded that the process of recombinant protein production by microbial cells under SMG was different from the secondary metabolites. We considered that SMG probably was a condition facilitating secretion of protein or even other biological macromolecules, especially extracellular secretion because of much higher up-regulated genes related to exocytosis or extracelluar secretion (such as PAS_chr3_0292, PAS_chr3_0347, PAS_chr4_0078 and PAS_chr2-2_0210). Furthermore, the genes of protein secretion were higher up-regulated than genes of protein transportation because genes of protein secretion might be more affected by SMG, or otherwise the method of GO classification was not very applicable in protein transportation or secretion. In addition, most of the tested 20 genes matched well in the two methods (NGS and real time RT-PCR) in spite of some difference in transcriptional profiling. The disparity in the expression levels of these genes using NGS and quantitative PCR analysis might be attributed to the differences in methanol induction process.

It seems that SMG can be regarded as a special kind of environment signal or stress that is quickly sensed by cells. The cells have to respond to the stress and ultimately adapt themselves to this environment, and then physiological changes of the recombinant P. pastoris could be observed. We concluded that enhanced production of the recombinant protein under SMG had close relation with the intensified transcriptional levels of two kind of key genes; in fact, our previous results and hypothesis had also been confirmed [15]. And we will proceed to further investigation of the mechanism through which microbial cells sense the reduced gravity conditions and also how they convert these mechanical signals into molecular and biochemical responses. This can give rise to the advanced knowledge about the pathway and mechanism of biological process under SMG.

Supporting Information

Sequencing saturation analysis of the gene tags libraries of P. pastoris GS115. (A) stationary phase and (B) exponential phase under SMG (S) and NG (N) environments, respectively.

(RAR)

Expression patterns of 20 significant genes related to methanol utilization under SMG compared with NG.

(DOC)

Expression patterns of 54 significant genes related to RNA polymerase under SMG compared with NG.

(DOC)

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work is supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (20976014) and Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (2112035). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Nickerson CA, Ott CM, Wilson JW, Ramamurthy R, Pierson DL. Microbial responses to microgravity and other low-shear environments. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:345–361. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.345-361.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klaus DM. Microgravity and its implications for fermentation biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:369–373. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(98)01197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwarz RP, Goodwin TJ, Wolf DA. Cell culture for three-dimensional modeling in rotating-wall vessels: an application of simulated microgravity. J Tissue Cult Methods. 1992;14:51–57. doi: 10.1007/BF01404744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johanson K, Allen PL, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Baker CB, D'Elia R, et al. Gene expression and survival changes in saccharomyces cerevisiae during suspension culture. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;93:1050–1059. doi: 10.1002/bit.20810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammond TG, Hammond JM. Optimized suspension culture: the rotating-wall vessel. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:12–25. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.1.F12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammond TG, Lewis FC, Goodwin TJ, Linnehan RM, Wolf DA, et al. Gene expression in space. Nat Med. 1999;5:359. doi: 10.1038/7331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nickerson CA, Ott CM, Wilson JW, Ramamurthy R, LeBlanc CL, et al. Low-shear modeled microgravity: a global environmental regulatory signal affecting bacterial gene expression, physiology, and pathogenesis. J Microbiol Meth. 2003;54:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(03)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demain AL, Fang A. Secondary metabolism in simulated microgravity. Chem Rec. 2001;1:333–346. doi: 10.1002/tcr.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang A, Pierson DL, Mishra SK, Demain AL. Relief from glucose interference in microcin B17 biosynthesis by growth in a rotating-wall bioreactor. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2000;31:39–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson JW, Ott CM, Bentrup KHZ, Ramamurthy R, Quick L, et al. Space flight alters bacterial gene expression and virulence and reveals a role for global regulator Hfq. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16299–16304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707155104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng SJ, Li C, Xu XL, Wang XY. Screening strains for directed biosynthesis of β-mono-glucuronide-glycyrrhizin and kinetics of enzyme production. J Mol Catal B-Enzym. 2006;43:63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsui S, Matsumoto H, Sonoda Y, Ando K, Aizu-Yokota E, et al. Glycyrrhizin and related compounds down-regulate production of inflammatory chemokines IL-8 and eotaxin 1 in a human lung fibroblast cell line. Int Immunol. 2004;4:1633–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cereghino JL, Cregg JM. Heterologous protein expression in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:45–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sreekrishna K, Brankamp RG, Kropp KE, Blankenshio DT, Tsay JT, et al. Strategies for optimal synthesis and secretion of heterologous proteins in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. Gene. 1997;190:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qi F, Kaleem I, Lv B, Guo XX, Li C. Enhancement of recombinant β-D-glucuronidase production under low-shear modeled microgravity in Pichia pastoris. J Chem Technol Biot. 2011;86:505–511. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roh SW, Abell GCJ, Kim KH, Nam YD, Bae JW. Comparing microarrays and next generation sequencing technologies for microbial ecology research. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook J, Russell DWJ. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3rd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang QQ, Liu F, Chen XS, Ma XJ, Zeng HQ. Transcriptome profiling of early developing cotton fiber by deep-sequencing reveals significantly differential expression of genes in a fuzzless/lintless mutant. Genomics. 2010;96:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill RT, Valdes JJ, Bentley WE. RT-PCR differential display analysis of Escherichia coli global gene regulation in response to heat shock. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5386–5393. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.12.5386-5393.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee EJ, Schmittgen TD. Comparison of RNA assay methods used to normalize cDNA for quantitative real-time PCR. Anal Biochem. 2006;357:299–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker PW, Meyer ML, Leff LG. Escherichia coli growth under modeled reduced gravity. Microgravity Sci Tec. 2004;15:39–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02870967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purevdorj-Gage B, Sheehan KB, Hyman LE. Effects of low-shear modeled microgravity on cell function, gene expression, and phenotype in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microb. 2006;72:4569–4575. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03050-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sequencing saturation analysis of the gene tags libraries of P. pastoris GS115. (A) stationary phase and (B) exponential phase under SMG (S) and NG (N) environments, respectively.

(RAR)

Expression patterns of 20 significant genes related to methanol utilization under SMG compared with NG.

(DOC)

Expression patterns of 54 significant genes related to RNA polymerase under SMG compared with NG.

(DOC)