Abstract

We have previously shown that, in vitro, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) labeled with the Auger electron emitter 125I are more cytotoxic if they remain at the cell surface and do not internalize in the cytoplasm. Here, we assessed in vivo the biological efficiency of internalizing and non internalizing 125I-labeled mAbs for the treatment of small solid tumors.

Methods

Swiss nude mice bearing intraperitoneal tumor cell xenografts were injected with 37 MBq (370 MBq/mg) of internalizing (anti-HER1) 125I-m225 or non-internalizing (anti-CEA) 125I-35A7 mAbs at day 4 and 7 following tumor cell graft. Non specific toxicity was assessed using the irrelevant 125I-PX mAb and untreated controls were injected with NaCl. Tumor growth was followed by bioluminescence imaging. Mice were sacrificed when the bioluminescence signal reached a value of 4.5×107 photons/s. Biodistribution analysis was performed to determine the activity contained in healthy organs and tumor nodules and total cumulative decays were calculated. These values were used to calculate the irradiation dose by the MIRD formalism.

Results

Median survival (MS) was 19 days in the NaCl-treated group. Similar values were obtained in mice treated with unlabeled PX (MS = 24 days) and 35A7 (MS = 24 days), or with 125I-PX mAbs (MS = 17 days). Conversely, mice treated with unlabeled or labeled internalizing m225 mAb showed a significant increase in survival (MS = 76 days and 77 days, respectively) as well as mice injected with 125I-35A7 mAb (MS = 59 days). Irradiation doses were comparable in all healthy organs independently from the mAb used, whereas, in tumors, the irradiation dose was 7.4 fold higher with 125I-labeled non-internalizing than with internalizing mAbs. This discrepancy might be due to iodotyrosine moiety release occurring during the catabolism of internalizing mAbs associated to high turnover rate.

Conclusion

This study indicates that 125I-labeled non-internalizing mAbs could be suitable for radioimmunotherapy of small solid tumors, and that the use of internalizing mAbs should not be considered as a requirement for the success of treatments with 125I Auger electrons.

Keywords: Animals; Antibodies, Monoclonal; chemistry; metabolism; pharmacokinetics; therapeutic use; Biological Transport; Cell Line, Tumor; Female; Iodine Radioisotopes; chemistry; Isotope Labeling; Mice; Peritoneal Neoplasms; metabolism; pathology; radiotherapy; Radioimmunotherapy; Radiometry; Survival Rate; Tissue Distribution; Tumor Burden

Keywords: radioimmunotherapy, Auger electrons, solid tumors

INTRODUCTION

Development of clinically effective radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) has been limited to the treatment of lymphomas. Indeed, only Zevalin and Bexxar, two anti-CD20 mAbs conjugated to 90Y and 131I, respectively, have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the therapy of lymphomas (1). Conversely, the few candidates for the therapy of solid tumors that have progressed to phase III clinical trials have not given clear-cut results (2, 3, 4).

This can be explained by inhomogeneous targeting related to poor vascularization and high interstitial pressure due to insufficient lymphatic drainage (5–9). Uptake of radioactivity in solid tumors is generally between 0.001% and 0.01% of the injected dose per gram of tumor and is inversely proportional to the tumor’s size. In addition, solid tumors show low sensitivity to radiations. Therefore, myelotoxicity is usually attained before the dose required for tumor eradication is reached inside the cancer mass. Consequently, it is now admitted that, in case of solid tumors, radioimmunotheapy (RIT) should be considered only for the treatment of small tumors (10, 11), microscopic residual disease, or metastasis (12).

The other issue concerns the choice of emitter used to label the mAbs. The two strong energy beta emitters (i.e., 90Y and 131I) produce electrons having ranges between 2 and 10 mm, respectively. The long range of energetic beta particle of 90Y and γ rays associated with 131I are responsible for non-specific irradiation that may cause undesirable effects like myelosuppression. However, in mice, several studies showed that 131I-mAbs could efficiently treat micro-metastases (size below 1 mm), but not tumors of 2—3 mm in size (13, 14). Other emitters, like high linear energy transfer (LET) particles, may be more attractive candidate for the therapy of solid tumors. They include alpha- and Auger electron-emitting radionuclides. Alpha emitters, which are suitable for RIT, include mostly 212Bi or 225Ac/213Bi and 211At. Alpha particles have a short path length (<100 μm) that minimizes damage to normal tissues. They also possess a very high LET with energy deposit of about 100 keV/μm compared to 0.2 keV/μm of the beta emitters [for review (15)]. However, their use in RIT requires the development of cost-effective radionuclide production and protein labeling chemistry. Another drawback of alpha emitters is the production of radioactive daughter isotopes that can be hardly withheld in a chelator and tend to escape from targeted cells and accumulate in bone (16).

By contrast, Auger electron emitters are available for clinical use. Although Auger electron’s energy ranges from eV to about 20—25 keV, those with high LET characteristics (i.e., between 4 and 26 keV/μm) (17) have an energy comprised between few tens of eV and 1 keV and their path length in biological tissues ranges from about 2 nm to 500 nm. Therefore, in this work, we used the term “low-energy Auger electrons” to indicate this category of Auger electrons with high LET features. Several studies underscored the advantages of such emitters in comparison to conventional 131I and 90Y in RIT of solid tumors due to their much less toxic side effects (18–21). However, because of their short path length, their final localization within the cell has to be taken into account. Many studies using 125I-iododeoxyuridine highlighted the requirement for the emitter to be located within the DNA molecule to observe a cellular toxicity similar to that of alpha particles (22). However, in RIT, the final localization of radiolabeled mAbs is either the cytoplasm or the cell surface depending on whether internalizing or non-internalizing mAbs are used. We previously showed that, in vitro, non-internalizing 125I-mAbs were more harmful than internalizing ones. Although the strongest toxicity of 125I is observed when the isotope is incorporated within the DNA molecule (23–25), these results suggest that the cell membrane also is a sensitive target (26). Here, we investigated the efficacy of non-internalizing and internalizing 125I-mAbs in the treatment of mice with tumor cell xenografts. For this purpose, nude mice bearing intraperitoneal A-431-derived tumors were injected twice with 37 MBq of internalizing or non-internalizing 125I-mAbs. Tumor growth was followed by bioluminescence imaging and endpoint was a bioluminescence signal of 4.5× 107 photons/s. Our results demonstrate that 125I-mAbs are an efficient tool for the treatment of small solid tumors and that the use of internalizing 125I-mAb is not a pre-requisite for RIT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line and monoclonal antibodies

The vulvar squamous carcinoma cell line A-431 expressing the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR or HER1) was transfected with vectors encoding for the CarcinoEmbryonic Antigen (CEA) gene as described in (27) and for luciferase as described in (28). Cells were grown as described in (26) and medium was supplemented with 1% geneticin.

The mouse hybridoma cell line producing the m225 mAb, which binds to EGFR, was obtained from ATCC. The non-internalizing murine IgG1k 35A7 mAb, specific for the CEA Gold 2 epitope (29), was used to target CEA in transfected A-431 cells. The irrelevant PX antibody was used for control experiments. PX is an IgG1 mAb that has been purified from the mouse myeloma MOPC 21 (30). The m225, 35A7 and PX mAbs were obtained from mouse hybridoma ascites fluids by ammonium sulfate precipitation followed by ion exchange chromatography on DE52 cellulose (Whatman, Balston, United Kingdom).

Radiolabeling for therapy and biodistribution analysis

Iodine 125 (125I) and Iodine 131 (131I) were from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA, USA) and mAbs were radiolabeled as described in (26). Specific activity was generally around 370 MBq/mg. For RIT, two injections of 37 MBq (equivalent to 100 μg mAb) were used. For biodistribution experiments a solution containing 185 KBq of 125I-mAbs together with 320 KBq of 131I-mAbs, respectively, was completed with unlabeled mAbs to a final amount of 100 μg mAbs. Immunoreactivity of 125I-mAbs against CEA or EGFR was assessed in vitro by direct binding assays. The binding percentage was determined by measuring the antigen-bound radioactivity after 2 washes with PBS and ranged from 70 to 90%.

Animals

Swiss nude mice (6–8 week/old females) were obtained from Charles River (Lyon, France) and were acclimated for 1 week before experimental use. They were housed at 22°C and 55% humidity with a light/dark cycle of 12h. Food and water were available ad libitum. Body weight was determined weekly and clinical examinations were carried out throughout the study. Experiments were performed in compliance with the French guidelines for experimental animal studies (Agreement no. B34-172-27).

Radioimmunotherapy experiments and tumor imaging

For RIT experiments, Swiss nude mice were intraperitoneally grafted with 0.7 × 106 A-431 cells suspended in 0.3 ml DMEM medium. Tumor growth was assessed 3 days after cell xenograft by bioluminescence imaging and animals were segregated in homogeneous groups according to the type of treatment (i.e., NaCl, 125I-m225, 125I-35A7 and 125I-PX or unlabeled m225, 35A7 and PX mAbs).

Then, 37 MBq 125I-mAbs (specific activity = 370 MBq/mg), NaCl or unlabelled mAbs (100 μg) were intravenously injected at day 4 and 7 after the graft. Tumor growth was followed weekly by bioluminescence imaging. Mice were sacrificed when the bioluminescence signal reached a value of 4.5× 107 photons/s. In summary, 31 mice were included in the NaCl group, 13 in the PX, 14 in the 35A7, 7 in the m225, 19 in the 125I-PX, 12 in the 125I-35A7 and 6 in the 125I-m225 group.

A third intravenous injection of 125I-m225 or 125I-35A7 mAbs was carried out in two additional groups of mice (n= 7 for each 125I-mAb) at day 10 and animals were followed until the bioluminescence signal reached a value of 4.5× 107 photons/s or until death.

Bioluminescence imaging

In vivo bioluminescence imaging was performed following intraperitoneal injection of luciferin (0.1 mg luciferin/g) and as described in (28).

Biodistribution experiments

On day 1, 48 Swiss nude mice were intraperitoneally grafted with 0.7 × 106 A-431 cells suspended in 0.3 ml DMEM medium. Mice were then separated into two groups. Group one received one single intravenous injection of labeled mAbs at day 4, while group two received two intravenous injections (day 4 and 7). Injected solutions (250 μL) were made up of 100 μg of 35A7 or m225 mAbs containing 185 KBq of 125I-mAb (specific activity = 370 MBq/mg), and of 100 μg of irrelevant PX mAb containing 320 KBq of 131I-PX (specific activity = 370 MBq/mg). Mice of group one were sacrificed at 1, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 168h after the injection and mice from group two at the same time points but after the second injection. At each time point, animals were anaesthetized, image acquisition was performed and then they were euthanized, bled and dissected. Blood, tumor nodules and organs were weighed and the uptake of radioactivity (i.e., UORBiodis ) was measured with a γ-well counter. Dual isotope counting, 125I versus 131I, was done. The percentage of injected activity per gram of tissue (%IA/g), corrected for the radioactive decay, was calculated. For time points later than 72h (i.e., after the second injection), the injected activity of group two was defined as the sum of the residual radioactivity due to injection 1 and of the radioactivity due to injection 2. We assumed that the radioactivity detected in the different organs of mice from group 1 after this time point was not specifically bound to receptors any longer and could be mobilized again in the blood circulation. Four mice were used for each time point.

In addition, a control group of mice injected only with NaCl was sacrificed at the same time points as the animals used for the biodistribution analysis to follow the natural growth of the tumors.

Tumor weight assessment

In RIT experiments, direct measurement of tumor size could not be performed because it requires mice sacrifice and also because of the high activities. Therefore, we used the intensity of the bioluminescence signal collected weekly after tumor graft to determine tumor size. To do this we used biodistribution data to calibrate the bioluminescence signal (photons/s) as a function of tumor size. The values of the bioluminescence signal of tumor nodules were collected at different time points during the biodistribution analysis and plotted versus their weight directly determined as follows. Initially, tumor nodules were weighed. However, these values appeared to be less accurate than estimation from size measurement because of blood or water content, or contamination by other tissues. Therefore, their length, width and depth were measured at each time point of the biodistribution study and used for volume determination. A density of 1.05g/cm3 was then used for calculating the weight of each nodule.

Uptake of radioactivity per organ and tumor

The uptake of radioactivity per tissue (expressed in Becquerel) in RIT experiments (UORRIT) was extrapolated from the uptake per tissue (UORBiodis) measured during biodistribution experiments. Since activities used in RIT experiments were 200 times higher than those used in biodistribution analysis for the same amount of injected mAbs (100 μg), all the UORBiodis values were multiplied by 200 to mimic the therapeutic conditions. We considered that the weight of healthy tissues did not change all along the study period and did not differ between RIT and biodistribution experimental conditions. Therefore, the 200-fold factor’s rule was enough to determine the UORRIT from UORBiodis. However, since tumors were smaller in animals subjected to RIT than in controls, their UORRIT was calculated by taking also into consideration this weight variation. Hence, the real tumor weight was assessed as follows: UORBiodis per gram of tumor was calculated by dividing UORBiodis by the measured tumor weight. This value was then multiplied by the calculated weight of the tumor in RIT conditions (as described in “Tumor weight assessment”). This approach was supported by the finding that in biodistribution studies uptake of radioactivity increased in a linear way with the tumor size. Thus, we could extrapolate the UOR from large to small tumors and calculate their UORRIT. The end point of the analysis was calculated by hypothesizing that the remaining activity at 240h would exponentially decrease to reach a value lower than 1% IA/g at 700h.

Dosimetry

The total cumulative decays per tissue were calculated by measuring the area under the UORRIT curves. Following the MIRD formalism, resulting values were multiplied by the S factor. This parameter was calculated by assuming that all the energy delivered at each decay was locally absorbed and we checked that the contribution of X and γ-rays could be neglected (31). A global energy of 19.483 keV/decay was then considered for calculating the irradiation doses.

Statistical analysis

A linear mixed regression model (LMRM), containing both fixed and random effects (32, 33), was used to determine the relationship between tumor growth (assessed by bioluminescence imaging) and number of days post-graft. The fixed part of the model included variables corresponding to the number of post-graft days and the different mAbs. Interaction terms were built into the model; random intercepts and random slopes were included to take into account time. The coefficients of the model were estimated by maximum likelihood and considered significant at the 0.05 level.

Survival rates were estimated from the date of the xenograft until the date of the event of interest (i.e., a bioluminescence value of 4.5×107 photons/s) using the Kaplan-Meier method. Median survival was presented and survival curves compared using the Log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using the STATA 10.0 software.

RESULTS

Tumor growth assessment

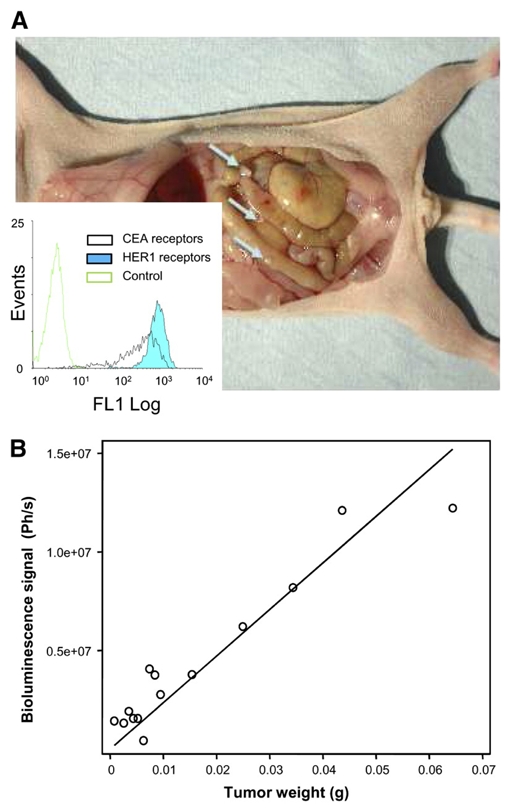

The presence of tumor nodules in control mice was observed as early as 3—4 days after the graft of A-431 cells (Figure 1A). Total number of tumor nodules per mouse and their size increased with time. For example, the mean number of nodules in control mice was 2.7±0.9 at day 4, 4.8±0.8 at day 7 and 6.6±3 at day 20 after graft. Mean tumor weight was 1.4±0.9 ×10−2 g at day 4, 4.2 ±0.9 ×10−2 g at day 7 and 16±0.7×10−2g at day 20. Similar tumor growth rates were observed in mice treated with unlabeled 35A7 or PX mAbs, whereas tumor growth was much slower in the group treated with unlabeled m225. Presence of ascite was never observed throughout the study and the number of collected nodules always corresponded to the number of bioluminescence spots.

Figure 1.

Tumor growth and bioluminescence calibration curves. A) Swiss nude mice bearing 1—2 mm xenograft A-431 tumor nodules were followed by bioluminescence imaging. Flow cytometry analysis (inset) indicated similar levels of expression of EGFR and CEA receptors at the surface of A-431 cells. B) In vivo relationship between bioluminescence signal and mean tumor weight per mouse.

To indirectly measure tumor size in mice subjected to RIT, we calibrated the bioluminescence signal (photons/s) as a function of tumor size. We used a linear relationship to plot the signal intensity of control tumor nodules versus their weight. This procedure was satisfying only for tumors weighing less or about 1×10−1 g (Figure 1B). For bigger tumor nodules, the dose-response relationship was saturated and therefore tumor size was underestimated. Indeed, according to the calibration curve, the value of 4.5×107 photons/s should correspond to a mean tumor weight of about 2×10−1 g, whereas, upon dissection, the real tumor weight was 2—3 ×10−1 g.

Tumor growth in RIT experiments

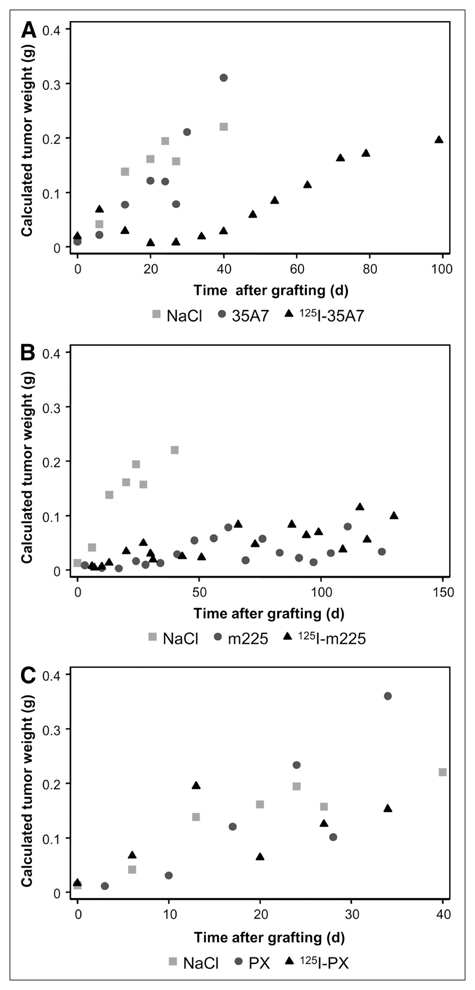

Tumor growth followed by bioluminescence imaging (Suppl. Fig. 2A, B, C) rose similarly among mice treated with NaCl or unlabeled PX and 35A7 mAbs (Figure 2A, 2C). While no changes in tumor growth were observed with 125I -PX mAbs (Figure 2C), treatment with 125I -35A7 mAbs slowed down tumor growth and endpoint values of 2—3 ×10−1 g were only reached at day 99 after xenograft (Figure 2A). The internalizing m225 mAbs had a strong inhibitory effect on tumor growth both in the unlabeled and labeled form (Figure 2B). Indeed, mean tumor weight in mice treated with m225 mAbs remained below 2 ×10−1 g for the entire duration of the study. This could be explained by the slower and heterogeneous growth rate of tumors in m225-treated mice compared to others groups. Therefore, sacrifice of m225-treated mice was less frequent than in the other groups and the highest registered signal did not affect the global mean bioluminescence value of this group.

Figure 2.

Swiss nude mice bearing intraperitoneal A-431 tumor cell xenografts were injected twice with 37 MBq of 125I-mAbs (370 MBq/mg) or with unlabelled mAbs (100 μg). A) non-internalizing 35A7 mAbs, B) internalizing m225 mAbs, C) irrelevant PX mAbs. Untreated controls were injected with NaCl. Tumor growth was followed by bioluminescence imaging. The corresponding mean tumor weights were next calculated using the calibration curve reported in Figure 1B and they are shown as a function of time in A, B, C, respectively..

Survival of mice exposed to therapeutic activities of 125I-labeled or unlabeled mAbs

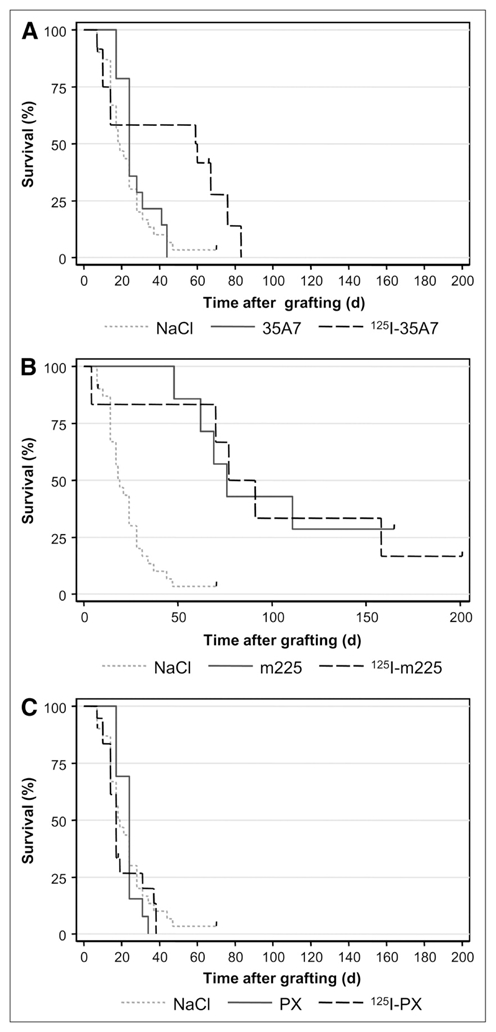

Mice were sacrificed when the bioluminescence signal reached 4.5×107 photons/s. The median survival (MS) was about 19 and 24 days in mice treated with NaCl or unlabeled 35A7, respectively. Conversely, survival was significantly higher in the group treated with 125I-35A7 mAbs (MS=59 days; p=0.0132) (Figure 3A). Both unlabeled m225 (MS=76 days; p = 0.0014) and 125I-m225 mAbs (MS= 77 days; p = 0.9289) improved survival in comparison to NaCl (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Swiss nude mice bearing intraperitoneal A-431 tumor cell xenografts were intravenously injected twice with 37 MBq of 125I-mAbs (370 MBq/mg) or with unlabeled mAb (100 μg). A) Non-internalizing 35A7 mAbs, B) Internalizing m225 mAbs, C) Irrelevant PX mAb. Survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Mice were sacrificed when bioluminescence signal reached 4.5×107 photons/second. Censored mice are indicated on the graph by vertical bars.

No statistical difference was observed in the NaCl, the 35A7, the PX or 125I-PX groups (p= 0.3189 for NaCl vs 35A7, p = 0.9046 for NaCl vs PX; p = 0.5109 for NaCl vs 125I-PX; p = 0.5095 for PX vs 125I-PX) with MS = 19, 24 and 17 days, respectively, underscoring the low non-specific toxicity of 125I-mAb (Figure 3C).

To cope with the lower toxicity of Auger emitters towards the target tumors in comparison to beta emitters and to assess the side effects of repeated injections, a third injection of 37 MBq of 125I-mAbs (m225 or 35A7) was carried out at day 10 following xenografts in two additional groups of mice. In this case, mice treated with 125I-35A7 mAbs died before the bioluminescence signal reached 4.5×107 photons/s suggesting that the maximum tolerated dose was attained and MS dropped to 14 days. Conversely, a non significant increase in MS was observed in the 125I-m225 group (MS about 94 days) (data not shown).

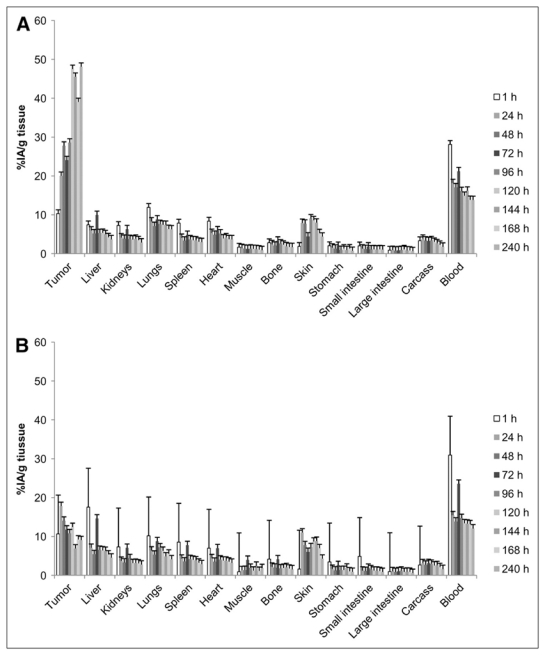

Biodistribution analysis

After injection of non-internalizing 125I-35A7 mAbs (Figure 4A), tumor uptake increased progressively from 10.5%, 1h after injection, to 48.1% after 120h. An intermediary value of 27.8% was observed at 48h. These results indicate that the maximal uptake of radioactivity per tumor was reached 2 days after the second injection.

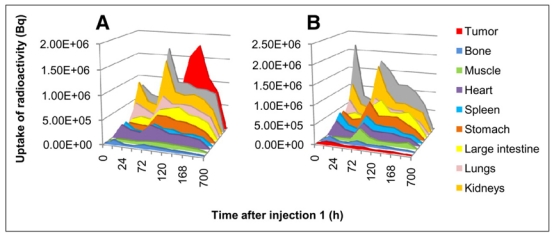

Figure 4.

Biodistribution. Swiss nude mice bearing intraperitoneal A-431 tumor cell xenografts were intravenously injected twice with a solution containing specific 125I-mAbs or irrelevant131I-PX as described in Materials and Methods. The percentage of injected activity per gram of tissue (%IA/g tissue) was determined in healthy organs and tumors. A) Non internalizing 125I-mAbs. B) Internalizing 125I-mAbs. Four mice were analyzed at each time point.

Maximal uptake in blood was 28.1±2.4% and 21.2±1.1% immediately after injection 1 and 2, respectively.

By contrast, tumor uptake of internalizing 125I-m225 mAbs was much lower (Figure 4B) with a maximal uptake of 17.8±6.8% observed 24h after injection 1 and no increase after injection 2. Uptake in blood was maximal immediately after injection 1 and 2 with values of 30.9±3.9 and 23.5±1.2% like with non-internalizing mAbs.

Non specific tumor uptake of the 131I-PX mAbs was comprised between 2.8±0.5 and 11.5±4.6% (with 125I-35A7) and between 5.9 ±3.2 and 9.7±1.8% (with 125I-m225) (data not shown).

For all the other organs, no significant differences were observed between the two targeting models and values were lower than those measured in tumors and blood.

Uptake of radioactivity per organ and tumor

The uptake of radioactivity per tissue (expressed in Becquerel) in RIT experiments (UORRIT) was extrapolated from the uptake per tissue (UORBiodis) measured during the biodistribution experiments and these values were plotted versus time (Figures 5A and B). Both targeting models presented similar UORRIT values in all tissues analyzed with the exception of tumors. Carcass, liver and blood contained the highest peak activity (10 MBq—30 MBq) because of their larger volume (Suppl. Fig. 5A and 5B), whereas the other organs showed lower values, generally below 1.7 MBq. Maximal peak uptake by tumors reached values of 1.8 MBq with non-internalizing and of 0.05 MBq with internalizing 125I-mAbs. For all the tissues, two peak values corresponding to the two injections were observed.

Figure 5.

Uptake of radioactivity. Uptake of radioactivity per tissue (Bq) was determined using the values obtained during the biodistribution experiments (see Figure 4) as described in Materials and Methods. A) Non internalizing 125I-mAbs. B) Internalizing 125I-mAbs.

Dosimetry

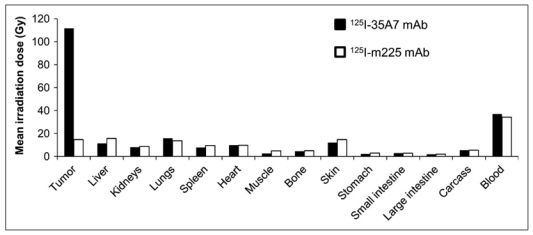

To obtain accurate information about the total energy absorbed by tumors and healthy organs we calculated their irradiation doses. The highest irradiation doses were delivered to tumors, blood, liver, skin and lungs and the lowest to small and large intestine and stomach (Figure 6). Similar irradiation doses were delivered by the two targeting models in healthy organs and tissues. Therapy with the internalizing 125I-m225 mAb produced slightly higher irradiation doses in stomach (+14.4%), liver (+16.3%), kidneys (+3.5%), muscle (+31.8%), small intestine (+1.1%), large intestine (+3.9%), bone (+5.1%) and skin (+9.9%). Conversely, lower irradiation doses were calculated for lungs (−7.4%) and blood (−7.0%). For heart and carcass less than 1% discrepancy in irradiation doses was determined between both targeting models. However, a huge difference was observed in tumors since internalizing mAbs delivered only 15.1 Gy in comparison to the 111.6 Gy of non-internalizing mAbs.

Figure 6.

MIRD dose calculation. From Figure 5, total cumulative decays per tissue, Ã, was calculated by measuring the area under each curve. Ã was next multiplied by 19.483 keV, corresponding to the mean energy delivered at each 125I decay.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the efficiency of 125I-labeled internalizing and non-internalizing mAbs in eradicating small solid intraperitoneal tumors. We show that labeling of the non-internalizing 35A7 mAb was accompanied by a statistically significant increase in the median survival (MS) from 24 days (controls) to 59 days. Unlabeled m225 mAb showed by itself a very strong efficiency with a MS of 76 days that was not improved by labeling with 125I. The standard treatment of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis is based on cytoreductive surgery followed by heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) (34); however, several studies have started to compare the efficiency of RIT versus HIPEC. For instance, Aarts et al. targeted, in rats, carcinomatosis of about 1 mm after cytoreductive surgery with RIT or HIPEC. They obtained a MS of 97 days (versus 57 days in untreated controls) after one intraperitoneal injection of 74 MBq of 177Lu- MG1 mAbs and of 76 days with HIPEC (35). Moreover, they showed that RIT was less detrimental for healthy tissues (36). Our study indicates that significant increase in MS could be achieved also with 125I-mAbs and suggests that 125I-mAbs could be as efficient as 177Lu-mAbs in the case of small tumors.

More experiments need, however, to be performed because direct comparison between studies cannot be accurate due to the different experimental models used and, particularly, the possibility of variable radiation sensitivity of the targeted tumor cells.

Compared to conventional more energetic beta emitters, the interest of Auger electrons emitters relies on their very low myelotoxicity that allows repeated injections (18, 19). This is important as it has been speculated that the failure of phase III trial with 90Y-HMFG1 in ovarian cancers was linked to the low irradiation dose delivered by a single administration [for review (37)]. Therefore, by using low-energy Auger electrons the injected activities could be increased in order to cope with their lower tumor toxicity and a therapeutic gain of about 2 in comparison to beta emitters has been already demonstrated (38). Here, we show that, in the mouse, two injections of 37 MBq of 125I-mAbs are well tolerated and greatly increase MS. However, mice which received a third injection of 125I-35A7 mAbs died before the bioluminescence signal reached 4.5×107 photons/s. These results suggest that the maximum tolerated dose was reached and that the maximal therapeutic gain, under our experimental conditions, is obtained with two injections of 125I-mAbs time over 3 days. Studies are under way to determine the toxic effects of this regimen on bone marrow, although overt signs of myelotoxicity were not observed.

Conjugation to 125I was accompanied by a significant increase in survival (i.e., 40 days) in the case of the non-internalizing mAb 35A7, whereas labeling did not further increase the positive effect of the internalizing mAbs m225. Moreover, the mean irradiation dose for tumors was 111.6 Gy with 125I-35A7 and 15.1 Gy with 125I-m225. These findings indicate that labeling m225 with 125I does not improve its therapeutic efficiency, mainly because the delivered irradiation dose was too low. This was not due to lack of EGFR expression in A-431 cells because flow cytometry analysis revealed that CEA and HER1 antigens were expressed at similar level (Figure 1A). Since 35A7 and m225 immunoreactivity and immunoaffinity are comparable in vitro, we think that catabolism of internalizing mAbs must have been the cause of the low number of total cumulative decays in tumors treated with 125I-m225, an effect linked to its short retention time within the tumor. Indeed, the %IA/g of tumors reached 48.1% with 125I-35A7, but only 17.8% with 125I-m225. Internalizing 125I-mAbs are catabolized within the cells and one of the catabolism products is a diffusible iodotyrosine moiety. Methodologies aimed at producing residualizing peptides, which can be conjugated to mAbs before the iodination process, have been developed. In this case, catabolism produces iodinated residual peptides that are trapped within the lysosomes to increase tumor retention time (39–42). However, with residualizing peptides tumor irradiation could be increased by a factor of 3–4, while in our study a 7.4 fold increase (i.e., from 15.1 Gy to 111.6 Gy) was observed with non-internalizing mAbs in comparison to internalizing mAbs. Moreover, the high turnover rate of cell surface antigens represent a limiting factor for mAb penetration within solid tumors (43).

Nevertheless, the limits of dosimetry in the case of Auger electrons must be kept in mind. Indeed, since most of the energy is delivered within a sphere of several nm around the decay site, the calculation of the mean irradiation dose for an organ or even for a cell could lead to approximations that do not take into account the real dose distribution. If this type of approximation is acceptable in the case of low LET radiations, like gamma rays, the correlation between mean irradiation dose and biological effects must be used carefully in the case of high LET particles, particularly in the case of low-energy Auger electrons. Indeed, due to the strong heterogeneity of the energy deposits, some areas of a tumor nodule could be not irradiated and cells therein could grow in spite of a high mean tumor dose. In our study, mean calculated irradiation doses might appear rather high. This can be explained by a strong initial uptake of 125I-35A7 mAb by tumors (48.1%) that led us to consider a long interval (700h) before reaching the endpoint of 1% IA/g of tumor. Then, dose rate is finally rather low and would explain the lack of overt toxicities towards safe tissues. Behr et al. have reported radiation absorbed doses to the blood up to 24.3 Gy in mice administered 125I-CO17-1A mAbs at a maximum tolerated dose of 111 MBq (18). These radiation absorbed doses are almost identical to those estimated for 125I-35A7 mAb using a similar observation period of 500 h (20.1 Gy; not shown) but exceed by about 10-fold those normally found to be dose-limiting for energetic β-emitters, indicating a different relationship between radiation absorbed dose and biological effect for Auger electron emitters.

Another point could be that inhomogeneous UOR in solid tumors could alter the linearity of the relationship between tumor mass and UOR that was used for dosimetric assessment. Therefore calculated irradiation doses could be overestimated.

Our study is in agreement with our previous in vitro study showing that the cell membrane (targeted by non-internalizing mAbs) was sensitive to 125I decays (26). Non-internalizing 125I-mAbs might produce strong energy deposits which are localized at the cell membrane, while internalizing 125I-mAbs mostly segregate within lysosomes. However, these conclusions cannot probably be extrapolated to other Auger electron emitters, like 111In, 123I or 67Ga. Indeed, although their disintegration produces 8, 11 and 20 Auger electrons, respectively, with energy ranging from 12 eV to 24 keV [for review (44)], their decays are also associated to more or less energetic photons rays or conversion electrons that contribute mostly to the irradiation dose. For this reason, 125I can be considered the Auger electrons emitter that produces the most localized energy deposits and the lowest toxic side effects. One of the main drawbacks of 125I for clinical use is its rather long physical period. However, this could be minimized if 125I-mAbs were administered following HIPEC, because the latter procedure allows to remove non-cell bound radiolabeled antibody from the peritoneal cavity.

Conclusion

We show that growth of solid tumors can be significantly reduced and survival of mice improved by RIT with 125I-labeled non-internalizing mAbs.

Catabolism of internalizing 125I- mAbs, labeled with non-residualizing labeling methods, release diffusible iodotyrosine moieties. This might explain the drastically reduced efficiency of these antibodies in our study, preventing accurate comparison between cytoplasmic and cell surface localizations. However, these results confirm our previous in vitro work showing that the cell membrane is sensitive to 125I decays. They indicate that the use of internalizing mAbs, that drive radioactivity in cell in close proximity to the nucleus, is not a pre-requisite to the success of a therapy with 125I.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Electricité de France-Service de Radioprotection. The authors would like to thank Imade Ait Arsa for animals care and involvement in experiments.

References

- 1.Davies AJ. Radioimmunotherapy for B-cell lymphoma: Y90 ibritumomab tiuxetan and I(131) tositumomab. Oncogene. 2007 May 28;26(25):3614–3628. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oei AL, Verheijen RH, Seiden MV, et al. Decreased intraperitoneal disease recurrence in epithelial ovarian cancer patients receiving intraperitoneal consolidation treatment with yttrium-90-labeled murine HMFG1 without improvement in overall survival. Int J Cancer. 2007 Jun 15;120(12):2710–2714. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verheijen RH, Massuger LF, Benigno BB, et al. Phase III trial of intraperitoneal therapy with yttrium-90-labeled HMFG1 murine monoclonal antibody in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer after a surgically defined complete remission. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Feb 1;24(4):571–578. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.5973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koppe MJ, Postema EJ, Aarts F, Oyen WJ, Bleichrodt RP, Boerman OC. Antibody-guided radiation therapy of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005 Dec;24(4):539–567. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-6195-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain RK. Lessons from multidisciplinary translational trials on anti-angiogenic therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008 Apr;8(4):309–316. doi: 10.1038/nrc2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams LE, Bares RB, Fass J, Hauptmann S, Schumpelick V, Buell U. Uptake of radiolabeled anti-CEA antibodies in human colorectal primary tumors as a function of tumor mass. Eur J Nucl Med. 1993 Apr;20(4):345–347. doi: 10.1007/BF00169812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain M, Venkatraman G, Batra SK. Optimization of radioimmunotherapy of solid tumors: biological impediments and their modulation. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Mar 1;13(5):1374–1382. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain R. Physiological barriers to delivery of monoclonal antibodies and other macromolecules in tumors. Cancer Res. 1990 Fév;50(3 Suppl):814s–819s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thurber GM, Zajic SC, Wittrup KD. Theoretic criteria for antibody penetration into solid tumors and micrometastases. J Nucl Med. 2007 Jun;48(6):995–999. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.037069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharkey RM, Pykett MJ, Siegel JA, Alger EA, Primus FJ, Goldenberg DM. Radioimmunotherapy of the GW-39 human colonic tumor xenograft with 131I-labeled murine monoclonal antibody to carcinoembryonic antigen. Cancer Res. 1987 Nov 1;47(21):5672–5677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koppe M. Radioimmunotherapy and colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005 Mar;92(3):264–276. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behr TM, Liersch T, Greiner-Bechert L, et al. Radioimmunotherapy of small-volume disease of metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2002 Feb 15;94(4 Suppl):1373–1381. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharkey RM, Weadock KS, Natale A, et al. Successful radioimmunotherapy for lung metastasis of human colonic cancer in nude mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991 May 1;83(9):627–632. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.9.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogel CA, Galmiche MC, Buchegger F. Radioimmunotherapy and fractionated radiotherapy of human colon cancer liver metastases in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1997 Feb 1;57(3):447–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Couturier O, Supiot S, Degraef-Mougin M, et al. Cancer radioimmunotherapy with alpha-emitting nuclides. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005 May;32(5):601–614. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1803-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sofou S, Kappel BJ, Jaggi JS, McDevitt MR, Scheinberg DA, Sgouros G. Enhanced retention of the alpha-particle-emitting daughters of Actinium-225 by liposome carriers. Bioconjug Chem. 2007 Nov-Dec;18(6):2061–2067. doi: 10.1021/bc070075t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kassis AI. Radiotargeting agents for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2005 Nov;2(6):981–991. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2.6.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behr TM, Sgouros G, Vougiokas V, et al. Therapeutic efficacy and dose-limiting toxicity of Auger-electron vs. beta emitters in radioimmunotherapy with internalizing antibodies: evaluation of 125I- vs. 131I-labeled CO17-1A in a human colorectal cancer model. Int J Cancer. 1998 May 29;76(5):738–748. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980529)76:5<738::aid-ijc20>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behr TM, Behe M, Lohr M, et al. Therapeutic advantages of Auger electron- over beta-emitting radiometals or radioiodine when conjugated to internalizing antibodies. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000 Jul;27(7):753–765. doi: 10.1007/s002590000272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michel RB, Brechbiel MW, Mattes MJ. A comparison of 4 radionuclides conjugated to antibodies for single-cell kill. J Nucl Med. 2003 Apr;44(4):632–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michel RB, Castillo ME, Andrews PM, Mattes MJ. In vitro toxicity of A-431 carcinoma cells with antibodies to epidermal growth factor receptor and epithelial glycoprotein-1 conjugated to radionuclides emitting low-energy electrons. Clin Cancer Res. 2004 Sep 1;10(17):5957–5966. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kassis AI, Adelstein SJ. Radiobiologic principles in radionuclide therapy. J Nucl Med. 2005 Jan;46(Suppl 1):4S–12S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kassis AI. Radiotargeting agents for cancer therapy. Expert Opin drug deliv. 2005;2(6):981–991. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2.6.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofer KG. Biophysical aspects of Auger processes. Acta Oncol. 2000;39(6):651–657. doi: 10.1080/028418600750063686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofer KG, Lin X, Schneiderman MH. Paradoxical effects of iodine-125 decays in parent and daughter DNA: a new target model for radiation damage. Radiat Res. 2000 Apr;153(4):428–435. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2000)153[0428:peoidi]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pouget JP, Santoro L, Raymond L, et al. Cell membrane is a more sensitive target than cytoplasm to dense ionization produced by auger electrons. Radiat Res. 2008 Aug;170(2):192–200. doi: 10.1667/RR1359.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelegrin A, Terskikh A, Hayoz D, et al. Human carcinoembryonic antigen cDNA expressed in rat carcinoma cells can function as target antigen for tumor localization of antibodies in nude rats and as rejection antigen in syngeneic rats. Int J Cancer. 1992;52(1):110–119. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pillon A, Servant N, Vignon F, Balaguer P, Nicolas JC. In vivo bioluminescence imaging to evaluate estrogenic activities of endocrine disrupters. Anal Biochem. 2005 May 15;340(2):295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammarstrom S, Shively JE, Paxton RJ, et al. Antigenic sites in carcinoembryonic antigen. Cancer Res. 1989 Sep 1;49(17):4852–4858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohler G, Howe SC, Milstein C. Fusion between immunoglobulin-secreting and nonsecreting myeloma cell lines. Eur J Immunol. 1976 Apr;6(4):292–295. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830060411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boutaleb S, Pouget JP, Hindorf C, et al. Impact of mouse model on pre-clinical dosimetry in Targeted Radionuclide Therapy. Proceedings of the IEEE; 2009. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mc Culloch CSS. Generalized, linear, and mixed models. New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982 Dec;38(4):963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ceelen WP, Hesse U, de Hemptinne B, Pattyn P. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemoperfusion in the treatment of locally advanced intra-abdominal cancer. Br J Surg. 2000 Aug;87(8):1006–1015. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aarts F, Hendriks T, Boerman OC, Koppe MJ, Oyen WJ, Bleichrodt RP. A comparison between radioimmunotherapy and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis of colonic origin in rats. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007 Nov;14(11):3274–3282. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9509-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aarts F, Bleichrodt RP, de Man B, Lomme R, Boerman OC, Hendriks T. The Effects of Adjuvant Experimental Radioimmunotherapy and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy on Intestinal and Abdominal Healing after Cytoreductive Surgery for Peritoneal Carcinomatosis in the Rat. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008 Aug 19; doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meredith RF, Buchsbaum DJ, Alvarez RD, LoBuglio AF. Brief overview of preclinical and clinical studies in the development of intraperitoneal radioimmunotherapy for ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Sep 15;13(18 Pt 2):5643s–5645s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barendswaard EC, Humm JL, O’Donoghue JA, et al. Relative therapeutic efficacy of (125)I- and (131)I-labeled monoclonal antibody A33 in a human colon cancer xenograft. J Nucl Med. 2001 Aug;42(8):1251–1256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stein R, Govindan SV, Mattes MJ, et al. Improved iodine radiolabels for monoclonal antibody therapy. Cancer Res. 2003 Jan 1;63(1):111–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaidyanathan G, Affleck DJ, Bigner DD, Zalutsky MR. Improved xenograft targeting of tumor-specific anti-epidermal growth factor receptor variant III antibody labeled using N-succinimidyl 4-guanidinomethyl-3-iodobenzoate. Nucl Med Biol. 2002 Jan;29(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(01)00277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharkey RM, Karacay H, Cardillo TM, et al. Improving the delivery of radionuclides for imaging and therapy of cancer using pretargeting methods. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Oct 1;11(19 Pt 2):7109s–7121s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1004-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurth M, Pelegrin A, Rose K, et al. Site-specific conjugation of a radioiodinated phenethylamine derivative to a monoclonal antibody results in increased radioactivity localization in tumor. J Med Chem. 1993 Apr 30;36(9):1255–1261. doi: 10.1021/jm00061a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ackerman ME, Pawlowski D, Wittrup KD. Effect of antigen turnover rate and expression level on antibody penetration into tumor spheroids. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008 Jul;7(7):2233–2240. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kassis AI. Cancer therapy with Auger electrons: are we almost there? J Nucl Med. 2003 Sep;44(9):1479–1481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]