Summary

The Bacillus subtilis stressosome is a 1.8 MDa complex that orchestrates activation of the σB transcription factor by environmental stress. The complex comprises members of the RsbR co-antagonist family and the RsbS antagonist, which together form an icosahedral core that sequesters the RsbT serine-threonine kinase. Phosphorylation of this core by RsbT is associated with RsbT release, which activates downstream signaling. RsbRA, the prototype co-antagonist, is phosphorylated on T171 and T205 in vitro. In unstressed cells T171 is already phosphorylated; this is a prerequisite but not the trigger for activation, which correlates with stress-induced phosphorylation of RsbS on S59. By contrast, phosphorylation of RsbRA T205 has not been detected in vivo. Here we find (i) RsbRA is additionally phosphorylated on T205 following strong stresses; (ii) this modification requires RsbT; and (iii) the phosphorylation-deficient T205A substitution greatly increases post-stress activation of σB. We infer that T205 phosphorylation constitutes a second feedback mechanism to limit σB activation, operating in addition to the RsbX feedback phosphatase. Loss of RsbX function increases the fraction of phosphorylated RsbS and doubly phosphorylated RsbRA in unstressed cells. We propose that RsbX both maintains the ready state of the stressosome prior to stress, and restores it post-stress.

Keywords: SigB, RsbR, signal transduction, protein phosphorylation, proteome

Introduction

Bacteria manifest diverse adaptive responses to adjust their physiology to changing surroundings. In Bacillus subtilis and the related pathogens Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus, the general stress regulon controlled by σB plays a prominent role in this strategy, interacting with other response systems to form flexible adaptive networks (reviewed in Hecker et al., 2007; Hecker et al., 2009; Price, 2010). Our focus here is the signal transduction pathway that activates B. subtilis σB in response to environmental stresses, and the feedback mechanisms that damp this activation. Key elements of this pathway are also found in a variety of signaling contexts, and in phylogenetically diverse bacteria (Pané-Farré et al., 2005). Our study is therefore relevant to understanding the operation of a versatile and widespread bacterial signaling module.

In B. subtilis and related organisms, σB activity is regulated by a signaling network that employs the partner switching mechanism, in which interactions between alternative binding partners are governed by serine and threonine phosphorylation (Hecker et al., 2007; Price, 2010). The B. subtilis network includes two independent branches that converge on the RsbV and RsbW regulators of σB (Fig. 1A). Each of these independent branches terminates with a differentially regulated serine phosphatase required for response to a discrete class of stress signal: RsbU for environmental or RsbP for energy stresses. In unstressed cells σB is held inactive by the RsbW anti-σ factor, which also acts as a serine kinase to phosphorylate and inactivate the RsbV anti-anti-σ. Following stress, one or another of the signaling phosphatases removes this modification from RsbV, allowing it to bind the RsbW anti-σ. Thus dephosphorylation of RsbV is the key event forcing RsbW to switch partners and release σB.

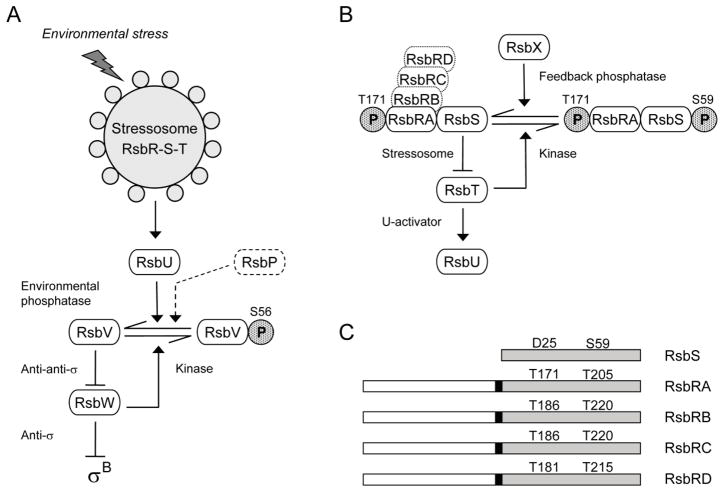

Figure 1. The σB regulatory network.

(A) Model of signaling pathways that regulate σB (modified from Hecker et al., 2007; Price, 2010). Environmental and energy pathways converge on RsbV and RsbW, which directly regulate σB activity (see text). The stressosome controls activation of the RsbU environmental phosphatase in response to diverse signals; the RsbP energy phosphatase is represented only in dotted outline. Horizontal arrows show conversion between RsbV and RsbV-P (with phosphate as stippled P). Full arrowheads indicate activating effects and T-headed lines inhibiting ones. (B) Model of stressosome control of RsbU phosphatase activity. The stressosome comprises the RsbRA, RB, RC, and RD co-antagonists and the RsbS antagonist, which together bind the RsbT kinase. In unstressed cells RsbT phosphorylates RsbRA on T171; we establish here that RsbT is also required for phosphorylation of RB on T186, RC on T186, and RD on T181. During the stress response, RsbRA-T171-P enhances the activity of the RsbT kinase, which inactivates its RsbS antagonist by phosphorylating S59; RsbT is released to bind and activate the RsbU environmental phosphatase. The RsbX feedback phosphatase dephosphorylates RsbS, damping continued signaling. (C) The RsbS antagonist consists of a single STAS domain (shaded), whereas the RsbR co-antagonists have an N-terminal, non-heme globin domain (open) connected to a C-terminal STAS domain by a 13 residue linker (black rectangle). Conserved threonine residues are indicated in the STAS domains of the RsbR proteins, together with the corresponding aspartate and serine residues of RsbS. These threonine and serine residues are the known or presumed sites of phosphorylation by RsbT.

Genetic, biochemical and structural studies support a model in which upstream regulators in the environmental pathway activate the RsbU phosphatase by means of a second partner switch, defined by the 1.8 MDa stressosome complex (Hecker et al., 2007; Marles-Wright et al., 2008; Price, 2010). Due to the greater number of components in this second switch, the role of phosphorylation in controlling its operation is less well understood. As shown in Fig. 1B, the switch comprises the RsbT serine kinase and the RsbS antagonist, which are paralogs of RsbW and RsbV, respectively, and also one or more members of the RsbR co-antagonist family: RsbRA, RB, RC or RD (Akbar et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2004a; Delumeau et al., 2006; Reeves et al., 2010). The switch target is the RsbU phosphatase, and RsbT serves as a positive regulatory subunit that activates RsbU by direct protein-protein interaction (Yang et al., 1996; Delumeau et al., 2004).

Structural studies have shown that the RsbS antagonist and the RsbR co-antagonists have related Sulfate Transporter Anti-Sigma Antagonist (STAS) domains that form the core of the stressosome complex, onto which the RsbT kinase binds (Marles-Wright et al., 2008). RsbS consists of a single STAS domain (Fig. 1C). In contrast, each RsbR co-antagonist also possesses an N-terminal, non-heme globin domain; these form projections from the surface of the stressosome and are thought to sense stress signals, which are presumably conveyed to the C-terminal STAS domains via a 13 residue helical linker. RsbRA, the prototype of the RsbR co-antagonist family, has both negative and positive roles (Akbar et al., 1997). The negative role reflects the requirement for RsbRA to act as a co-antagonist with RsbS to complex RsbT in the absence of stress; RsbS alone is unable to bind RsbT (Chen et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2004a). The positive role is thought to reflect the ability of RsbRA to enhance the phosphorylation of RsbS by RsbT (Gaidenko et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2004), an event associated with the stress-induced release of RsbT from the stressosome core and efficient activation of the environmental response (Kang et al., 1996; Chen et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2004b). Expression of a separate RsbX feedback phosphatase is under σB control. It dephosphorylates RsbS-P in vitro, and is proposed to complete a negative feedback loop that returns the system to its initial state (Yang et al., 1996: Voelker et al., 1997).

How the phosphorylation state of the RsbR co-antagonists might influence signal transduction is less clear. Biochemical analysis has shown that, in addition to its action toward RsbS on S59, RsbT also phosphorylates RsbRA on both T171 and T205, with T171 being the more readily modified in vitro (Gaidenko et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2004). The in vivo phenotypes elicited by phosphomimetic or phosphorylation-deficient substitutions at T171, together with analysis of the in vivo phosphorylation states of the RsbR family and RsbS, have been interpreted as evidence that RsbRA T171 phosphorylation is an important prerequisite but is not the trigger for signaling (Kim et al., 2004a; Kim et al., 2004b; Eymann et al., 2007). Instead, signaling appears to correlate with phosphorylation of RsbS on S59.

By contrast, T205 phosphorylation has not been unambiguously detected in vivo, and its physiological role remains unknown. Biochemical analysis found that stressosomes formed from doubly phosphorylated versions of RsbRA cannot bind RsbT in vitro, leading Chen et al. (2004) to suggest that simultaneous phosphorylation of T171 and T205 leads to robust σB activation. However, this proposal is inconsistent with the in vivo phenotypes of T205 substitutions: the phosphomimetic T205D decreases σB activation while the phosphorylation-deficient T205A increases it, suggesting that T205-P has a negative effect on signaling (Akbar et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2004a). To resolve these uncertainties, we sought conditions under which T205 becomes phosphorylated in vivo. Here we report this modification occurs when exponentially growing cells are exposed to strong environmental stresses. Based on mutant analysis, we propose that T205 phosphorylation represents a feedback mechanism that inhibits signaling under extreme conditions.

Results

In vivo phosphorylation of RsbRA T171 and the corresponding residues of its paralogs depends on the RsbT kinase

The paralogous proteins RsbRA (formerly RsbR), RsbRB (YkoB), RsbRC (YojH), and RsbRD (YqhA) possess two conserved threonine residues in their STAS domains (Fig. 1C). Our goals were to determine the growth conditions under which these conserved residues were phosphorylated in vivo, the contribution of the RsbT kinase and RsbX phosphatase, and the effects of these modifications on signaling. The four co-antagonists are functionally similar but are not identical (Kim et al., 2004a). We therefore focused on RsbRA, extending the analysis where possible to determine which characteristics were applicable to other members of the RsbR family.

Based on analysis of the in vivo phosphorylation state of wild and mutant forms of RsbRA, Kim et al. (2004a, 2004b) proposed that T171 is ordinarily phosphorylated in unstressed cells. In support of this proposal, a mass spectromic analysis showed that in exponentially growing cells the proteins RsbRA, RB, and RD are phosphorylated on T171, T186, and T181, respectively (Eymann et al., 2007). RsbRC was also phosphorylated under these conditions, but its amount was too low for verification of the residue. However, in a separate study employing gel-free analysis after biochemical enrichment to detect less abundant phosphoproteins, phosphorylation of RC on T186 was also verified by mass spectrometry (Macek et al., 2007).

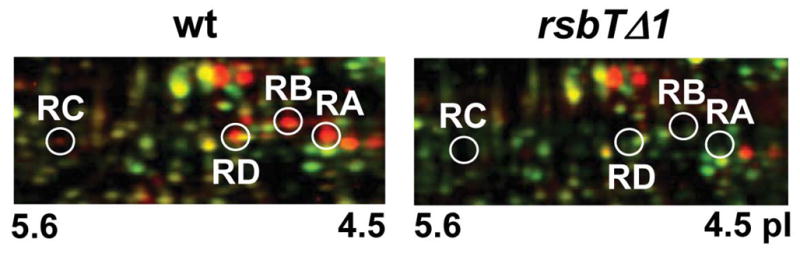

Here we demonstrate that these initial phosphorylation events, which take place in the absence of external stress, depend on the action of the RsbT kinase. Comparison of the proteomes of exponentially growing wild type and mutant cells, in which phosphorylated proteins were visualized by ProQ-Diamond®-staining, revealed the presence of all four phosphorylated RsbR paralogs in the wild type and their absence in the rsbT mutant (Fig. 2). Because RsbT phosphorylates all four RsbR paralogs in vitro (Akbar et al., 2001), the simplest interpretation of our results is that RsbT directly phosphorylates the RsbR paralogs in vivo.

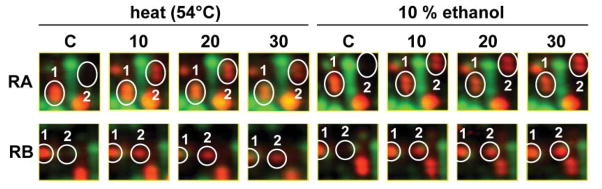

Figure 2. RsbT kinase activity is required for phosphorylation of RsbR proteins in unstressed cells.

Sections of dual channel images of phosphor-proteomes are shown. Proteins from exponentially-growing wild type (wt; PB2) and mutant cells (rsbTΔ1; PB421) were separated on two-dimensional gels and stained with ProQ-Diamond® (phosphorylated proteins = red color channel), then with Flamingo (all proteins = green color channel).

Occurrence of new RsbRA and RB isoforms in response to strong stresses

RsbT is known to phosphorylate RsbRA on T205 as well, but only from in vitro analysis (Gaidenko et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2004). We therefore looked for in vivo conditions under which RsbRA or its paralogs were phosphorylated on both conserved threonine residues. Notably, after exposure of exponentially-growing cells to strong, growth-preventing stresses (54°C or 10% ethanol), additional ProQ-stained isoforms of RsbRA and RB appeared at a more acidic position, suggesting the occurrence of an additional phosphorylation on each (Fig. 3). No additional isoforms of RsbRC or RD were detected. We therefore turned our attention to the new isoforms of RsbRA and RB.

Figure 3. New isoforms of RsbRA and RsbRB appear following strong heat or ethanol stress.

Relevant sections of dual channel images of the phosphor-proteome are shown. Time of stress is indicated in minutes; samples from wild type cells were separated and stained as in the Fig. 2 legend. For RsbRA (upper row) and RsbRB proteins (lower row), potential single- and double-phosphorylated isoforms are labelled (1) and (2), respectively. Note that the most acidic isoforms (double-phosphorylated, labelled 2) were detected only in response to stress.

Mass spectromic analysis confirmed that the second isoform of RsbRA (RsbRA-2) was phosphorylated on both T171 and T205 after strong stress. As shown in Table 1, both phosphorylations were found in two separate peptides of this second RsbRA protein spot, with high confidence. By contrast, for the second isoform of RsbRB (RsbRB-2), phosphorylation could be confirmed on T186 but not T220. This was due to the complete absence of the T220-containing peptide from our tryptic digests. The basis of the altered mobility of the second RsbRB spot is therefore not yet established.

Table 1.

MS/MS data of proteins identified after 10% ethanol stress

| Spot | Accession Number | Protein Name | Molecular Mass (Da) | Protein Identification Probability (%) | Peptide Identification Probability (%) | Coverage (%) | Number of Unique Peptides | Phosphorylation site | Phosphopeptide sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RsbRA1 | P42409 | RsbRA | 31050.70 | 100 | 95 | 64 | 12 | T171 | (K)IALQELSAPLIPVFENITVMPLVGTIDpTERAK(R) |

| RsbRA2 | P42409 | RsbRA | 31050.70 | 100 | 95 | 71 | 15 | T171 | (K)IALQELSAPLIPVFENITVmPLVGTIDpTER(A) |

| RsbRA2 | P42409 | RsbRA | 31050.70 | 100 | 95 | 71 | 15 | T205 | (R)SQVVLIDITGVPVVDpTmVAHHIIQASEAVR(L) |

| RsbRB1 | O34860 | RsbRB | 32387.60 | 100 | 95 | 53 | 13 | T186 | (K)STALLPLVGDIDpTER(A) |

| RsbRB2 | O34860 | RsbRB | 32387.60 | 100 | 95 | 63 | 14 | T186 | (K)STALLPLVGDIDpTER(A) |

pT = phosphorylated Threonine

m = oxidized methionine

Regarding RsbRA, it is worth mentioning that both its ProQ-stained isoforms sometimes manifested vertical double spots that differed in size, in which the double phosphorylated isoform had a higher molecular weight than the single phosphorylated one (Fig. 3). This phenomenon suggests that additional posttranslational modifications of RsbRA occur in vivo. The nature and significance of these additional modifications remain to be investigated.

Three distinct RsbRA or RsbRB isoforms detected by isoelectric focusing and Western blotting

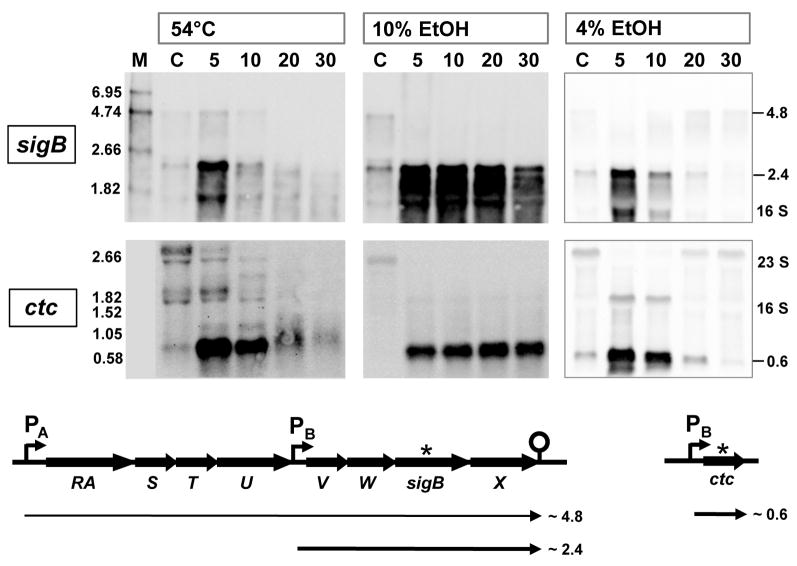

We were unable to detect non-phosphorylated RsbRA or RsbRB on 2D gels after Flamingo staining, suggesting these forms were present in only low amounts. In order to engage all the isoforms and quantitate the non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated fractions under different stress conditions, we separated the proteins in cell extracts by isoelectric focusing (IEF) and detected the isoforms by Western blotting with antibodies raised against RsbRA or RsbRB. Proteins were isolated from B. subtilis wild type cells cultivated under qualitatively and quantitatively different stresses. These included (i) heat shock (50 or 54°C); (ii) ethanol stress (4 or 10%, v/v); and (iii) sodium chloride stress (4 or 8%, w/v). The “mild” stress did not affect growth rate (50°C) and the “moderate” stresses reduced it by about half (4% ethanol, 4% NaCl). By contrast, the “strong” stresses stopped growth completely (54°C, 10% ethanol, 8% NaCl; growth data not shown). All these conditions induced σB activity to varying degrees, as measured by Northern blotting with RNA probes against the σB-dependent genes ctc and sigB (shown in Fig. 4 for 54°C, 4% and 10% ethanol stress).

Figure 4. Induction of σB-dependent message from sigB or ctc in response to heat or ethanol stress.

RNA probes were made against the σB-dependent genes sigB and ctc; these were used for Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated before (lane C) and at various times (in minutes) after stress, as described in Experimental procedures. Size standards (lane M) facilitated identification of gene-specific transcripts as well as rRNA species, indicted on the right. Organization of the sigB and ctc regions is shown beneath the blots, with σB-dependent promoters labelled PB, the source of the probe indicated by *, and the expected transcripts designated by bold arrows.

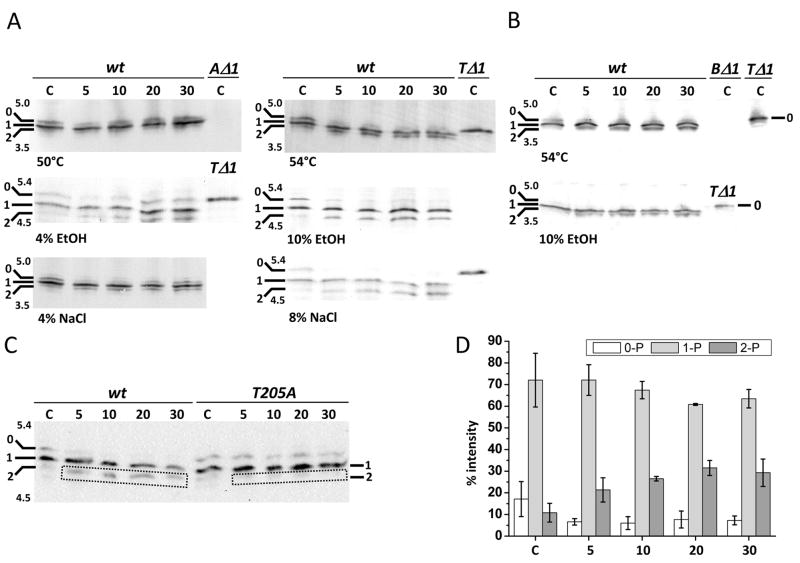

Proteins isolated from cells before and at different times after stress were separated on IEF gels; these contained pharmalytes based on the pI value of RsbRA (4.73) or RsbRB (4.79). As shown in Fig. 5A and B, Western blotting with antibody against RsbRA or RsbRB detected three significant signals, representing three different isoforms for each paralog. In previous work with this IEF system (Kim et al., 2004b), the three RsbRA signals were identified as non-phosphorylated (0), singly phosphorylated on T171 (1), and doubly phosphorylated on T171 and T205 (2). The evidence used in this earlier study included (i) incubations with λ phosphatase; (ii) analysis of a null mutant missing the RsbT kinase; and (iii) analysis of strains encoding mutant forms of RsbRA (T171 and T205 substitutions). However, the presence of some singly-phosphorylated T205 in the (1) signal of Fig. 5A cannot be precluded. The negative controls in Fig. 5A and B gave the patterns expected: only the non-phosphorylated (0) form of RsbRA or RsbRB appeared in extracts from an rsbT null mutant, and no signals were apparent in extracts from rsbRA or rsbRB null mutants.

Figure 5. Multiple isoforms are detected in crude cell extracts using anti-RsbRA or anti-RsbRB antibody.

(A & B) For IEF in the ranges indicated on the gel images, 50 μg of protein from wild type (PB2) cells isolated before (control, leftmost lane C) or at various times after exposure to heat (50°C, 54°C), ethanol (4%, 10%) or sodium chloride (4%, 8%) were loaded into each lane. Samples from unstressed rsbRA (AΔ1; PB427), rsbRB (BΔ1; PB545), or rsbT (TΔ1; PB421) null mutants were also analyzed (lane C on the right). Western blots were probed with anti-RsbRA (A) or anti-RsbRB (B); gel images are oriented with alkaline regions uppermost and with isoform positions (0, 1, 2) indicated on the left. (C) Blot using anti-RsbRA antibody to probe extracts of wild type (PB2) and rsbRA T205A mutant (PB505) cells isolated before (control, leftmost lane C) or at various times after exposure to 10% ethanol; isoform positions (0, 1, 2) indicated on the left. (D) Quantification of RsbRA isoform signals from three independent ethanol stress experiments. Isoforms (0-P, 1-P, 2-P) are shown as % of total RsbRA detected.

Analysis of RsbRA isoforms and phosphorylation patterns in response to stress

Under non-stress conditions two forms of RsbRA were detected in vivo (Fig. 5A). The first was the non-phosphorylated form (0), which was the only signal detected in the rsbT mutant. The second was the single phosphorylated form (1), most of which should correspond to the ProQ-spot modified on T171 (Fig. 3). Under stress conditions a third RsbRA isoform appeared as a significant signal. This was the doubly phosphorylated form (2), which should correspond to the ProQ-spot modified on T171 and T205 (Fig. 3). These latter forms (1 and 2) were undetectable in extracts of the rsbT mutant (Fig. 5A), indicating their RsbT dependence. To confirm the identity of the RsbRA isoforms, a strain encoding a T205A substitution was used for a further IEF experiment. As shown in Fig. 5C, in the T205A mutant no significant signal was detected for RsbRA isoform (2), either in unstressed cells or following a strong ethanol stress.

Quantification of the isoform signals from Fig. 5A revealed that in unstressed cells about 20% of the RsbRA was non-phosphorylated and about 70% was singly phosphorylated (see Fig. 5D). Under these conditions the doubly phosphorylated form represented only about 10% of total cellular RsbRA. However, as inspection of Fig. 5A shows, this doubly phosphorylated isoform significantly increased in response to those moderate or strong stresses that caused either growth rate reduction (4% EtOH, 4% NaCl) or growth rate stop (54°C, 10% EtOH, 8% NaCl). Such an increase did not occur in response to the mild 50°C stress, which did not affect growth rate. In the case of 10% ethanol stress, the fraction of doubly phosphorylated isoform increased to about 30% of the total while the non-phosphorylated fraction decreased (Fig. 5D). We obtained similar results with RsbRB following 54°C and 10% ethanol stresses (Fig. 5B): a decrease of the non-phosphorylated isoform (0); an increase of the presumed doubly phosphorylated isoform (2); and disappearance of isoform (2) in a mutant bearing an alanine substitution at the T220 position (data for the latter not shown).

We should note that the earlier study of Kim et al. (2004b) did not detect the doubly phosphorylated form of RsbRA, even though these authors employed a moderate 4% ethanol stress similar to the one shown in Fig. 5A. Two differences between the studies might account for this. First, we used a different mix of phosphatase inhibitors in the harvest buffer, including NaN3. And second, we used a synthetic minimal medium for cell growth rather than Luria broth, which may have rendered the 4% ethanol stress relatively stronger in our study.

Consequence of the inability to phosphorylate RsbR on T205

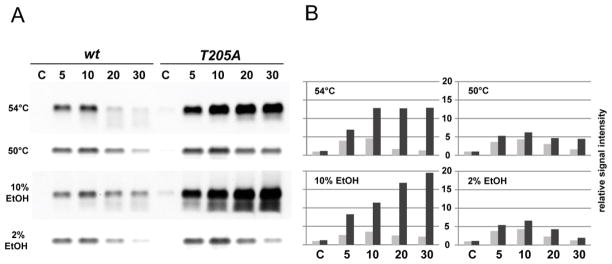

The question arises regarding the role that phosphorylation of RsbRA T205 might play in the σB signaling network. Is sequential phosphorylation on T171 and T205, together with phosphorylation of RsbS on S59, responsible for releasing RsbT from the stressosome and inducing σB activity, as suggested by Chen et al. (2004)? To test this possibility, we compared σB activity in wild type with that of a strain encoding the T205A form of RsbRA, in which T205 cannot be phosphorylated. The assay shown in Fig. 6 was done by Northern blotting against gsiB, whose expression is wholly dependent on σB (Maul et al., 1995). Following exposure of exponentially growing cells to 54°C or 10% ethanol -- conditions that promote T205 phosphorylation -- expression of gsiB message was greatly increased and sustained in the T205A mutant relative to wild type (Fig. 6). To support the idea that this difference reflected an inability to phosphorylate T205 and was not a general effect of the T205A substitution, we repeated the assay under conditions in which T205 would not be highly phosphorylated. Following exposure to 50°C or 2% ethanol, expression of gsiB message was only slightly elevated in the T205A mutant relative to wild type (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. T205A alteration in RsbRA greatly increases σB-dependent message levels during severe stress.

(A) Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated from the wild type (wt; strain PB2) or a mutant encoding the T205A alteration in rsbRA (T205A; strain PB505), subjected to either strong (54°C, 10% ethanol) or mild (50°C, 2% ethanol) stress for the indicated times (minutes). An RNA probe was used to monitor expression of the σB-dependent gene gsiB; control lane C indicates signal in unstressed cells. (B) Quantitation of the data shown in (A), expressed relative to that of the unstressed, wild-type control, taken as 1. Grey bars indicate gsiB expression in the wild type strain and black bars the T205A mutant.

Thus the T205A substitution did not diminish the stress response as predicted by the earlier in vitro analysis (Chen et al., 2004), but in fact greatly enhanced it. We infer from these results that the second phosphorylation of T205 is not involved in mounting the response, but instead is responsible for its attenuation. In an attempt to extend these observations to another member of the RsbR family, we performed a similar assay using the T220A mutant of RsbRB, which bears a substitution at the likely (but not experimentally demonstrated) second site of phosphorylation of that co-antagonist. However, the T220A alteration had no influence on gsiB expression following 10% ethanol or 54°C stress (data not shown).

The gsiB assays reported here agree with results obtained on similar strains using a ctc-lacZ reporter assay (Akbar et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2004a). In these earlier studies, strains bearing a T205A alteration manifested elevated σB activity following 4% ethanol stress in an otherwise wild type background, in which all four co-antagonists were present, as was the case for our gsiB assays here. The phenotype of the T205A alteration was even more pronounced in a strain in which the other known paralogs (RsbRB, RC and RD) were absent, and co-antagonist function was solely dependent on the T205A form of RsbRA (Kim et al., 2004a). Kim et al. also found that the RsbRB T220A alteration had no effect on σB activity, much as we observed in our assays. Thus the available data indicate that RsbRA and RsbRB have similar but not identical roles, and support the idea that phosphorylation of RsbRA T205 serves to attenuate σB activation in response to strong stress.

Role of the RsbX phosphatase

The RsbX feedback phosphatase is thought to return the system to its pre-stress state by dephosphorylating RsbS-S59-P (Yang et al., 1996; Voelker et al., 1997; Smirnova et al., 1998). The RsbRA co-antagonist and its paralogs are further potential substrates of RsbX; the conserved threonine residues in their STAS domains correspond to the D25 and S59 residues of RsbS (see Fig. 1C). In support of this notion, Chen et al. (2004) presented in vitro evidence that RsbX could dephosphorylate RsbRA-T205-P, but only when RsbRA was assembled into an intact stressosome with RsbS. These authors also found that RsbX manifested no activity toward RsbRA-T171-P under the same assay conditions.

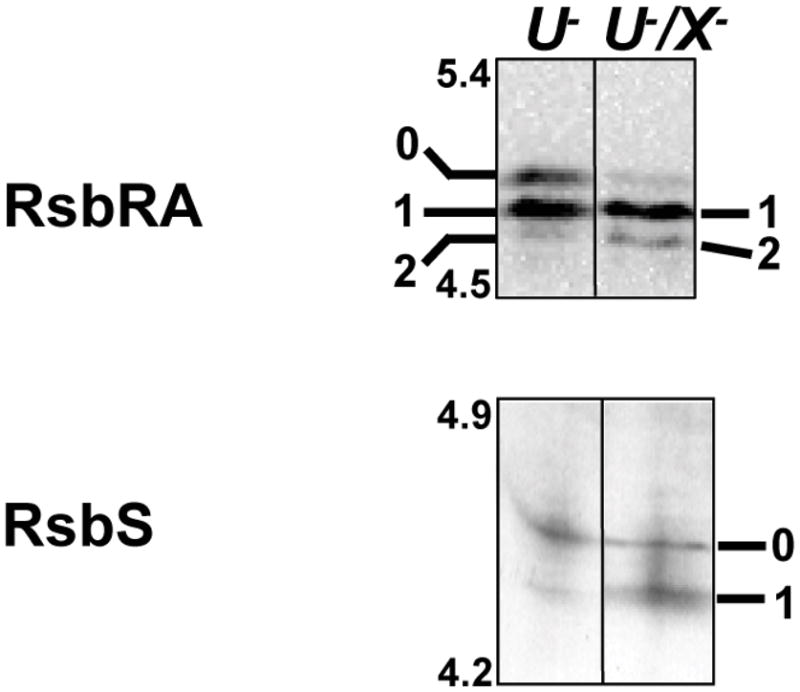

To investigate the in vivo influence of RsbX on the phosphorylation state of RsbRA, we compared RsbRA isoforms in strains that were wild or mutant at the rsbX locus. Because rsbX null alleles cause severe growth and viability defects due to high σB activity, we suppressed these phenotypes by using strains that also bore an rsbU null allele (Voelker et al., 1995). We first determined whether loss of RsbU phosphatase activity had any effect on the in vivo phosphorylation state of the RsbRA protein by comparing isoforms present in a wild type strain (BSA46) with those found in an rsbU null mutant (BSA70). As predicted by the model of the environmental signaling pathway (Fig. 1B), the phosphorylation pattern of RsbRA was not significantly affected in the rsbU null strain (data not shown). Because the rsbU alteration in these strains prevents induction of σB (and RsbX) synthesis in response to environmental stress, thereby breaking the negative feedback loop, we only examined the effects of the rsbX null allele in unstressed cells.

To test the activity of RsbX in vivo, proteins isolated from unstressed rsbU null (BSA70) and rsbU/rsbX double null mutants (BSA151) were separated by IEF and the different RsbRA isoforms were detected by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 7A, in the absence of any imposed stress there were significant differences between the two strains. Nearly all of the RsbRA was phosphorylated in the rsbX null mutant, and a significant portion was in the doubly phosphorylated form. This result indicates that dephosphorylation of at least one of the threonine residues requires RsbX in vivo. Based on the in vitro data of Chen et al. (2004), we presume that RsbX can directly dephosphorylate T205-P in vivo but has little or no activity toward T171-P. To test this proposed specificity, we repeated the experiment using strains bearing the T171A substitution. However, as others had observed in vitro (Gaidenko et al., 1999), this substitution also prevented T205 phosphorylation in vivo, and we were unable to assay RsbX activity against T205-P (data not shown).

Figure 7. RsbRA and RsbS are substrates for the RsbX phosphatase in unstressed cells.

Western blot analyses using anti-RsbRA (upper) or anti-RsbS (lower) antibody against IEF-separated crude cell extracts of unstressed strains bearing either a null allele in rsbU (U−; BSA70) or null alleles in both rsbU and rsbX (U−/X−; BSA151). Isoforms are 0 (unphosphorylated), 1 (singly phosphorylated) or 2 (doubly phosphorylated) for RsbRA; and 0 (unphosphorlylated) or 1 (singly phosphorylated) for RsbS.

In parallel with our analysis of the RsbRA co-antagonist, we examined the influence of RsbX on the phosphorylation pattern of the RsbS antagonist, using IEF and Western blotting against monoclonal RsbS antibody. RsbX is known to dephosphorylate RsbS-S59-P in vitro (Yang et al., 1996; Chen et al., 2004), but this activity has not been tested in vivo. As shown in Fig. 7B, in unstressed cells RsbS was more highly phosphorylated in the rsbU/rsbX double null than in the rsbU single null control. Coupled with the available in vitro data, this result supports the hypothesis that RsbX directly dephosphorylates S59-P in vivo.

Discussion

The stressosome is a large cytoplasmic complex that plays a central role in conveying the environmental cues that activate σB. However, the means by which the stressosome senses diverse signals as well as the mechanism of signal transduction within the stressosome itself are not well understood. These questions assume wider importance given the suggested role of RsbRST stressosome modules in controlling diverse signaling pathways in both Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria (Pané-Farré et al., 2005). Because the physiological role of the stressosome is known only in B. subtilis and the related L. monocytogenes, analysis of the molecular basis of its function has focused on the Bacillus model system.

Previous in vitro and in vivo analysis has pointed to the importance of serine or threonine modification in the signal transduction process: phosphorylation of RsbRA T171 is an important prerequisite for the response, and phosphorylation of RsbS S59 correlates with the onset of signaling (Fig. 1). However, the role of RsbRA T205 was unknown. Here we have shown that T205 becomes phosphorylated under strong stress conditions that cause either a significant growth rate decrease or a complete growth stop, and that this modification requires the RsbT kinase. We have also shown that a mutant bearing the T205A substitution has greatly enhanced σB activity under the same stress conditions. These results lead us to propose that T205 phosphorylation acts as a negative feedback mechanism to attenuate excessive response in the face of severe stress.

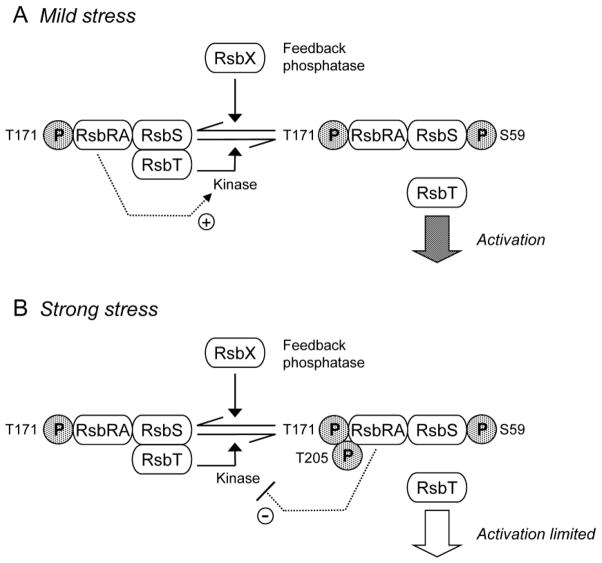

One possible basis of this attenuation is suggested by earlier in vitro experiments. RsbRA has a positive role in enhancing the phosphorylation of RsbS by RsbT, but phosphorylation of RsbRA on both T171 and T205 was found to abolish this enhancing activity (Gaidenko et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2004). In light of the data reported here, we propose the new model for environmental signaling shown in Fig. 8. In unstressed cells, RsbT phosphorylates RsbRA on T171, and the stressosome is poised to activate the response. When a stress signal is perceived, RsbRA facilitates phosphorylation of RsbS, which is associated with the release of RsbT to activate the RsbU environmental phosphatase. However, if the stress signal is strong, RsbT additionally phosphorylates RsbRA on T205, preventing efficient phosphorylation of RsbS and thus attenuating the response.

Figure 8. Model of stressosome function in response to different levels of environmental stress.

In unstressed cells RsbT phosphorylates the RsbRA co-antagonist on T171. (A) Following mild environmental stress, RsbRA-T171-P enhances activity of the RsbT kinase (+ arrow), which phosphorylates the RsbS antagonist on S59. This event correlates with release of RsbT from the complex, and RsbT activation of the RsbU phosphatase by direct protein-protein interaction. RsbX feedback phosphatase subsequently removes phosphate from S59, damping the general stress response. (B) Following strong environmental stress, RsbT additionally phosphorylates RsbRA on T205. We propose that doubly phosphorylated RsbRA no longer functions as a kinase activator (− arrow), limiting the general stress response. RsbX phosphatase then removes the phosphate from both RsbRA-T205 and RsbS-S59, resetting the system to function anew in unstressed cells.

This model is consistent with the in vivo phenotypes of D or A substitutions at T171 or T205, which are thought to mimic the phosphorylated or unphosphorylated states of these residues (Akbar et al., 1997; Gaidenko et al., 1999; Kim et al., 2004a). It is also consistent with the strong negative effect the T205D substitution has on interaction of RsbRA and RsbS in the yeast two-hybrid system (Akbar et al., 1997). RsbRA associates with RsbS in the stressosome (Chen et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2004a; Delumeau et al., 2006), and phosphorylation of RsbRA on T205 does not disrupt integrity of the complex in vitro (Chen et al., 2004). Thus the effect of T205D noted in the yeast two-hybrid system may reflect a change in the interaction of RsbRA and RsbS within the confines of the stressosome, once RsbRA becomes phosphorylated on T205. It remains to be determined whether this postulated change in fact impinges upon the ability of RsbRA to facilitate phosphorylation of RsbS by RsbT or otherwise disrupts signal flux through the stressosome.

Our experiments also support the hypothesis that serine-59 phosphate of RsbS and at least one of the threonine phosphates of RsbRA are direct targets of the RsbX feedback phosphatase in vivo (see Fig. 6). Other considerations suggest that RsbRA T205-P (and not T171-P) is dephosphorylated by RsbX in vivo, including the correspondence of the S59 residue in RsbS with the T205 residue in RsbRA (Fig. 1C) and the specificity of RsbX toward T205-P in vitro (Chen et al., 2004). The activity of RsbX is thought to be low in unstressed cells (Smirnova et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2004). This low activity is sufficient to maintain both RsbS and RsbRA in the ready but non-signaling state, with RsbS unphosphorylated and RsbRA phosphorylated mostly on T171 (Kim et al., 2004b). For RsbRA this state likely reflects the balance of RsbT kinase activity, with its preference for T171, and RsbX phosphatase activity, with its specificity for T205-P (Chen et al. 2004). For RsbS, kinase activity is presumably too low in unstressed cells to overcome the RsbX phosphatase. We therefore propose that one significant role of RsbX is to maintain this ready state in unstressed cells, with full capacity for signalling (involving phosphorylation of RsbS-S59) and attenuation (involving phosphorylation of RsbRA-T205).

We further suggest that during the stress response the sensitivity of these substrates to phosphorylation and dephosphorylation is such that RsbX can perform additional roles, depending on signal strength. Following mild stress, RsbT kinase activity would modestly exceed RsbX activity against S59; RsbS becomes phosphorylated, and σB is efficiently activated. Because its structural gene is under σB control, RsbX levels would then increase, leading to the eventual dephosphorylation of RsbS and attenuation of the response. By contrast, following strong stress, RsbT kinase activity would significantly exceed RsbX phosphatase activity, and RsbS becomes phosphorylated on S59 and RsbRA on T205. T205 phosphorylation would limit σB activation to a tolerable level, and the resulting increase in RsbX levels would eventually return the system to the ready state. In this view, RsbX has three roles: (i) a maintenance phosphatase in the absence of stress; (ii) a feedback phosphatase following response to mild stress; and (iii) a reset phosphatase following response to strong stress.

The environmental signaling branch of the σB network thus has two negative feedback loops – the previously described RsbX loop and the T205 loop proposed here. These results therefore identify a mechanism consistent with a previous study, which suggested that RsbX was not the only source of feedback in the system (Smirnova et al. 1998). What is the physiological role of these two different feedback circuits? Network modelling suggests the RsbX loop allows a rapid initial activation of σB by environmental stress, with some overshoot, and a subsequent readjustment to match the new steady-state condition (Igoshin et al., 2007). We now believe that this loop would function primarily under mild stress conditions. By contrast, the T205 loop would serve to attenuate the general stress response in the face of potentially lethal stresses. Under these conditions protein synthesis is restricted, and attenuation of the response may allow the cell to balance its resources among competing stress systems. The two feedback systems would thus have evolved to refine the interplay between them, allowing a flexible contribution from each to accommodate different stress levels.

Questions remain regarding the conserved threonine residues found in the RsbRB, RC and RD paralogs of B. subtilis, and the threonine (or serine) residues found in corresponding positions of the RsbR homologues of diverse bacteria (Krishnamurthy et al., 2006). Their preservation suggests functional importance, but the phenotypes of T186 and T220 substitutions in RsbRB indicate that their roles might differ in degree from T171 and T205 of RsbRA (Kim et al., 2004a; our unpublished results). Nonetheless, the present study underscores the importance of the RsbX feedback phosphatase in maintaining the ready state of the RsbRST signaling module. In this regard, we note that diverse bacterial genomes encoding this module often possess a closely linked gene for an RsbX-like protein phosphatase (Pané-Farré et al., 2005).

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

B. subtilis strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. Strains were cultivated under vigorous agitation (180 rpm) at 37°C in a synthetic minimal medium, as described previously (Stülke et al., 1993). Stress experiments were performed by (i) adding ethanol to a final concentration of 4% or 10% (v/v); (ii) adding sodium chloride to a final concentration of 4% or 8% (w/v); or (iii) shifting the culture from 37°C to 50°C or 54°C. Samples were taken at different times after the stress.

Table 2.

Bacillus subtilis strains

| B. subtilis strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| BSA46 | SPβ ctc::lacZ | Voelker et al., 1995 |

| BSA70 | rsbU::kan SPβ ctc::lacZ | Voelker et al., 1995 |

| BSA151 | rsbU::kan rsbX::spc SPβ ctc::lacZ | Voelker et al., 1995 |

| PB2 | trpC2 | Marburg strain |

| PB421 | rsbTΔ1 trpC2 | Akbar et al., 1997 |

| PB427 | rsbRAΔ1 trpC2 | Akbar et al., 1997 |

| PB545 | rsbRBΔ1::km trpC2 | Akbar et al., 2001 |

| PB505 | rsbRAT205A trpC2 | Akbar et al., 1997 |

| PB602 | rsbRBT220A trpC2 | Kim et al., 2004a |

Sample preparation, two-dimensional protein electrophoresis

Bacterial cells were harvested and washed twice with killing buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM NaN3 and 10 mM NaF (18.300 × g, 4°C, 10 min). The pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer containing 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF and 10 mM NaF. Cells were disrupted by ultrasonication and the soluble protein fraction separated from cell debris by centrifugation. Protein concentration was determined using Roti®-Nanoquant (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). 200 μg protein was separated by 2D PAGE as described previously (Eymann et al., 2004). Isoelectric focusing was done with commercially available 18-cm-IPG strips in the pH ranges 4–7 or 4.5–5.5 (GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany). 2D gels from the narrow pI gradients 4.5–5.5 were exclusively used for protein identifications by mass spectrometry (see below). Staining procedures with the fluorescence stains ProQ Diamond® and Flamingo (Molecular Probes) and image scanning were performed as described previously (Eymann et al., 2007).

Identification of RsbRA and RsbRB proteins and phosphate-containing peptides by mass spectrometry

Depending on signal intensity, up to seven Pro-Q-stained gel spots from replicate gels were manually cut and pooled into one tube. The gel pieces were washed twice with 200 μl of 20 mM NH4HCO3 in 30% (v/v) CH3CN for 30 min at 37°C, then dried in an Eppendorf Concentrator 5301 vacuum centrifuge. In-gel digestion with 10 ng/μl trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) in 20 mM NH4HCO3 was performed overnight at 37°C. Incubation of the gel pieces in an ultrasonic bath for 15 min in 20 μl HPLC-grade water resulted in peptide extraction. The supernatant was transferred into micro sample vials for mass spectrometric analysis. Peptides were separated and measured online by ESI-mass spectrometry using a nanoACQUITY UPLC™ system (Waters, Milford, MA) coupled to an LTQ Orbitrap™ mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). They were desalted onto a trap column (Symmetry® C18 5 μm, 180 μm inner diameter x 20 mm, Waters). Elution was performed onto an analytical column (BEH130 C18 1.7 μm, 100 μm inner diameter x 100 mm, Waters) by a binary gradient of buffer A (0.1% CH3COOH, v/v) and B (100% CH3CN in 0.1% CH3COOH, v/v) with a flow rate of 400 nl/min for 50 min. The LTQ Orbitrap was operated in data-dependent MS/MS mode, using multistage activation (MSA) for phospho relevant masses and the lockmass option for recalibration.

Proteins were identified by searching all MS/MS spectra in .dta format against all Bacillus subtilis proteins (extracted from the Uniprot-KB database: http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/?query=Bacillus+subtilis+168&sort=score) using “Sorcerer™-SEQUEST®” (Sequest v. 2.7 rev. 11, Thermo Electron) including “Scaffold_2_05_02” (Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR). Sequest search was performed applying a fragment ion mass tolerance of 1.00 Da and a parent ion tolerance of 10 ppm. Up to two tryptic miscleavages were allowed. Methionine oxidation (+15.99492 Da), cysteine carbamidomethylation (+57.021465 Da) and phosphorylation on serine, threonine and tyrosine (+79.966331 Da) were considered as variable modifications.

Proteins were identified by at least two peptides applying a probability score of greater than 99.9% (“Scaffold_2_02_03”; Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR). Protein probabilities were assigned by the Protein Prophet algorithm (Nesvizhskii et al., 2003). Phosphorylated peptides that have a peptide probability score greater than 95.0% as specified by the Peptide Prophet algorithm (Keller et al. 2002) were examined manually. They were only accepted when b- or y-ions confirmed the identification. Identified peptides are listed in Table 1.

IEF and Western blot (immunoblot) analysis

Cells were harvested and washed with killing buffer before ultrasonication in lysis buffer (buffer compositions given above). For IEF, 50 μg of protein extracts were mixed in a 1:1 volume with 2 × IEF sample buffer, loaded onto each lane of a mini-IEF-gel and separated as described by Kim et al. (2004b), with minor modifications. IEF sample buffer contained 2.6% (v/v) and the gel solution 4% (v/v) ampholytes (pH 3.5 – 5) or pharmalytes (pH 4.5 – 5.4 for RsbRA and RsbRB, or pH 4.2 – 4.9 for RsbS), together with 0.6% (v/v) pharmalytes (pH 3 – 10) and 1% (w/v) Triton X-100 (ampholytes and pharmalytes from GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany). After isoelectric focusing, gels were incubated for 30 minutes in solution 1: 50% (v/v) methanol, 1% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.6 M Tris pH 8; then for 30 minutes in solution 2: 50% (v/v) methanol, 1% (w/v) SDS, 0.4 M Tris pH 9.5. Equilibrated proteins were electroblotted at 100 V for 3 h to Immobilin-P membrane (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA), using transfer buffer containing 25 mM Tris pH 8.3, 193 mM glycine, 20% (v/v) methanol, 0.1% (w/v) SDS. Immunoblot detection has been described previously (Voelker et al., 1995). Monoclonal anti-RsbRA and anti-RsbS antibodies (Dufour et al., 1996) were kindly provided by Uwe Völker. The polyclonal anti-RsbRB antibody was described by Kim et al. (2004a); it was purified by adsorption against an acetone powder (Harlow and Lane, 1988) made from rsbRB deletion mutant PB545. Antibody specificity was confirmed by Western blot analysis of wild-type and mutant cell extracts separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Detection and quantification of specific signals was done using the Roche Lumi-Imager™ F1 Workstation and Roche Lumi-Analyst software 3.0.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA isolation and Northern blot analyses were performed as described previously (Wetzstein et al., 1992). RNA of B. subtilis wild-type and mutant strains was isolated during exponential growth (for control) and at different time points after exposure to ethanol or heat stress. Hybridizations specific for sigB, ctc and gsiB were conducted with digoxigenin-labelled RNA probes synthesized in vitro with T7 RNA polymerase from T7 promoter-containing internal PCR products of sigB, ctc or gsiB. The following primers were used for PCR, respectively (T7 polymerase promoter sequence underlined): sigB-for (5′-CACAACCATCAAAAACTACG-3′) and sigB-rev (5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGATAAGGCTTGATAGCTTTTGC-3′); ctc-for (5′-AGAACGGACTTTACTCGTTC-3′) and ctc-rev (5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAAGGCTTGAAATATCAGCCTC-3′); gsiB-for (5′-ATGGCAGACAATAACAAAATGAG-3′) and gsiB-rev (5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGTCGTTGTTGCGGGCGTTTCCGCC-3′). A Roche Lumi-Imager™ F1 Workstation was used to detect gsiB message signals; these were quantified with ImageJ 1.42q (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) and expressed relative to the controls, whose signal intensities were taken as 1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Uwe Völker and William Haldenwang for providing strains and monoclonal antibodies against RsbRA and RsbS; Jörg Bernhardt for creating Figure 2 by means of the software Delta 2D; and Tanya Gaidenko for her critical comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by Grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (HE 1887/7-4; HE 1887/8-1) and the BMBF (0313978A) (to MH), and by Public Health Service Grant GM42077 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (to CWP).

References

- Akbar S, Gaidenko TA, Kang CM, O’Reilly M, Devine KM, Price CW. New family of regulators in the environmental signaling pathway which activates the general stress transcription factor σB of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1329–1338. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1329-1338.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbar S, Kang CM, Gaidenko TA, Price CW. Modulator protein RsbR regulates environmental signalling in the general stress pathway of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:567–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3631732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Lewis RJ, Harris R, Yudkin MD, Delumeau O. A supramolecular complex in the environmental stress signalling pathway of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1657–1669. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Yudkin MD, Delumeau O. Phosphorylation and RsbX-dependent dephosphorylation of RsbR in the RsbR-RsbS complex of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:6830–6836. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.20.6830-6836.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delumeau O, Chen CC, Murray JW, Yudkin MD, Lewis RJ. High-molecular-weight complexes of RsbR and paralogues in the environmental signaling pathway of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:7885–7892. doi: 10.1128/JB.00892-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delumeau O, Dutta S, Brigulla M, Kuhnke G, Hardwick SW, Völker U, et al. Functional and structural characterization of RsbU, a stress signaling protein phosphatase 2C. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40927–40937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour A, Voelker U, Voelker A, Haldenwang WG. Relative levels and fractionation properties of Bacillus subtilis σB and its regulators during balanced growth and stress. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3701–3709. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3701-9sigma.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eymann C, Becher D, Bernhardt J, Gronau K, Klutzny A, Hecker M. Dynamics of protein phosphorylation on Ser/Thr/Tyr in Bacillus subtilis. Proteomics. 2007;7:3509–3526. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eymann C, Dreisbach A, Albrecht D, Bernhardt J, Becher D, Gentner S, et al. A comprehensive proteome map of growing Bacillus subtilis cells. Proteomics. 2004;4:2849–2876. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidenko TA, Yang X, Lee YM, Price CW. Threonine phosphorylation of modulator protein RsbR governs its ability to regulate a serine kinase in the environmental stress signalling pathway of Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:29–39. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. pp. 632–633. [Google Scholar]

- Hecker M, Pané-Farré J, Völker U. SigB-dependent general stress response in Bacillus subtilis and related gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:215–236. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker M, Reder A, Fuchs S, Pagels M, Engelmann S. Physiological proteomics and stress/starvation responses in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. Res Microbiol. 2009;160:245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igoshin OA, Brody MS, Price CW, Savageau MA. Distinctive topologies of partner-switching signaling networks correlate with their physiological roles. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:1333–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang CM, Brody MS, Akbar S, Yang X, Price CW. Homologous pairs of regulatory proteins control activity of Bacillus subtilis transcription factor σB in response to environmental stress. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3846–3853. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3846-3853.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem. 2002;74:5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TJ, Gaidenko TA, Price CW. A multicomponent protein complex mediates environmental stress signaling in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 2004;341:135–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TJ, Gaidenko TA, Price CW. In vivo phosphorylation of partner switching regulators correlates with stress transmission in the environmental signaling pathway of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:6124–6132. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.18.6124-6132.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy N, Brown DP, Kirshner D, Sjölander K. PhyloFacts: an online structural phylogenomic encyclopedia for protein functional and structural classification. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R83. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-9-r83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macek B, Mijakovic I, Olsen JV, Gnad F, Kumar C, Jensen PR, Mann M. The serine/threonine/tyrosine phosphoproteome of the model bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:697–707. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600464-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marles-Wright J, Grant T, Delumeau O, van Duinen G, Firbank SJ, Lewis PJ, et al. Molecular architecture of the “stressosome,” a signal integration and transduction hub. Science. 2008;322:92–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1159572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maul B, Völker U, Riethdorf S, Engelmann S, Hecker M. σB-dependent regulation of gsiB in response to multiple stimuli in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;248:114–120. doi: 10.1007/BF02456620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JW, Delumeau O, Lewis RJ. Structure of a nonheme globin in environmental stress signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17320–17325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506599102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesvizhskii AI, Keller A, Kolker E, Aebersold R. A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2003;75:4646–4658. doi: 10.1021/ac0341261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pané-Farré J, Lewis RJ, Stülke J. The RsbRST stress module in bacteria: a signalling system that may interact with different output modules. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;9:65–76. doi: 10.1159/000088837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CW. General stress response in Bacillus subtilis and related Gram positive bacteria. In: Storz G, Hengge R, editors. Bacterial Stress Responses. 2. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press; 2010. pp. 301–318. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves A, Martinez L, Haldenwang W. Expression of, and in vivo stressosome formation by, single members of the RsbR protein family in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 2010;156:990–998. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.036095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova N, Scott J, Voelker U, Haldenwang WG. Isolation and characterization of Bacillus subtilis sigB operon mutations that suppress the loss of the negative regulator RsbX. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3671–3680. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3671-3680.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stülke J, Hanschke R, Hecker M. Temporal activation of ®-glucanase synthesis in Bacillus subtilis is mediated by the GTP pool. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2041–2045. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-9-2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelker U, Dufour A, Haldenwang WG. The Bacillus subtilis rsbU gene product is necessary for RsbX-dependent regulation of σB. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:114–122. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.114-122.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelker U, Luo T, Smirnova N, Haldenwang W. Stress activation of Bacillus subtilis σB can occur in the absence of the σB negative regulator RsbX. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1980–1984. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1980-1984.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzstein M, Völker U, Dedio J, Lobau S, Zuber U, Schiesswohl M, et al. Cloning, sequencing, and molecular analysis of the dnaK locus from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3300–3310. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3300-3310.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Kang CM, Brody MS, Price CW. Opposing pairs of serine protein kinases and phosphatases transmit signals of environmental stress to activate a bacterial transcription factor. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2265–2275. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]