Abstract

Lead (Pb2+) exposure continues to be an important concern for fish populations. Research is required to assess the long-term behavioral effects of low-level concentrations of Pb2+ and the physiological mechanisms that control those behaviors. Newly fertilized zebrafish embryos (<2 hours post fertilization; hpf) were exposed to one of three concentrations of lead (as PbCl2): 0, 10, or 30 nM until 24 hpf. 1) Response to a mechanosensory stimulus. Individual larvae (168 hpf) were tested for response to a directional, mechanical stimulus. The tap frequency was adjusted to either 1 or 4 taps/sec. Startle response was recorded at 1000 fps. Larvae responded in a concentration-dependent pattern for latency to reaction, maximum turn velocity, time to reach Vmax and escape time. With increasing exposure concentrations, a larger number of larvae failed to respond to even the initial tap and, for those that did respond, ceased responding earlier than control larvae. These differences were more pronounced at a frequency of 4 taps/sec. 2) Response to a visual stimulus. Fish, exposed as embryos (2–24 hpf) to Pb2+ (0–10 uM) were tested as adults under low light conditions (~60 μW/m2) for visual responses to a rotating black bar. Visual responses were significantly degraded at Pb2+ concentrations of 30 nM. These data suggest that zebrafish are viable models for short- and long-term sensorimotor deficits induced by acute, low-level developmental Pb2+ exposures.

Keywords: behavior, lead, mechanosensory, startle response, visual, zebrafish

1. INTRODUCTION

Lead (Pb2+) exposure continues to be an important concern for fish populations (Mueller et al. 2011; Ebrahimi and Taherianfard 2010; Buekers et al. 2009; Hinck et al. 2006; Schmitt et al. 2006). While Pb2+ has been shown to be an endocrine disruptor (Iavicoli et al. 2009; Levesque et al. 2003; Weber 1993), it is most known for its effects on neuronal function and neurodevelopment (Neal et al. 2011; Reddy et al. 2007; Costa et al. 2004; Oberto 1996). Numerous studies have identified mechanisms of Pb2+ neurotoxicity, especially the long-term outcomes due to gestational exposures in mammals (Basha and Reddy 2010; Dearth et al. 2004, 2002; Yang et al. 2003; Devoto et al. 2001). Less research has been conducted to identify critical periods of development that are particularly sensitive to Pb2+ and whose toxic effects are observed at later time points in life (Bunn et al. 2001). Among the long-term changes identified to date are learning deficits (Sun et al. 2005; Carvan et al. 2004) and altered responses to environmental stimuli (Moreira et al. 2001; Morgan et al. 2001). This study was designed to focus on the effects on locomotor function due to low-level, developmental Pb2+ exposure.

Significant work has focused on Pb2+-induced alterations in learning and memory in a variety of vertebrate species (e.g., Carvan et al. 2004 [zebrafish]; Kuhlmann et al. 1997; Cory-Slechta 1995a, b [rats]; Stickler-Shaw and Taylor 1991 [frogs]). Pb2+ toxicity in fish also manifests itself through changes in locomotor activity patterns (Weber and Spieler 1994) and sensorimotor responses (Weber et al. 1997). A subset of such studies exists for studies on vertebrate species, specifically rats, analyzing the effects of low-level developmental Pb2+ on these particular behaviors (Leasure et al. 2008; Dietrich et al. 1985; Reiter et al. 1975); no studies examine the effect of very low-level Pb2+ exposure when isolated only to the ontogenetic periods in which neural network development occurs.

To fill the gap in our knowledge about the effects of low-level, developmental Pb2+ exposures in fishes, this study used larval zebrafish to assess changes in specific components of the startle response, the reaction to a directional stimulus, a behavior that is one of the first to be observed in newly hatched fishes. Fish embryos are particularly sensitive to environmental contaminants, especially within the first 24 hours post fertilization (Lahnsteiner 2008). In that regard, the following questions were asked: Do acute, very low-level developmental Pb2+ exposures cause sensorimotor deficits? If so, are the resulting behavioral phenotypes concentration-dependent even at these low exposure levels? If that is also true, do those effects extend to later life-history stages? Are the observed effects more pronounced in specific aspects of the startle response and escape swim? Answers to these questions will provide a foundation for examinations into how Pb2+ differentially alters neurodevelopment and behavioral outcomes.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Treatment of Glassware and Plasticware

All laboratory materials made of plastic were washed thoroughly in a 10% solution of a nontoxic, biodegradable detergent (Simple Green™; Sunshine Makers, Inc., Huntington Harbour, CA), rinsed repeatedly in ultra-pure Milli-Q™ water (Millipore Corp., Medford, MA), and immersed in a 30mM Na4EDTA (Fisher Scientific, Hanover Park, IL) solution overnight to remove all surface adsorbed metal ions; glassware was washed and rinsed similarly but immersed in a 10% HNO3 (Fisher Scientific, Hanover Park, IL) solution overnight. Glass and plasticware were then rinsed in ultra-pure Milli-Q™ water.

2.2 Breeding and Egg Collection

Adult zebrafish from a wild-type laboratory strain originally acquired as aquarium fish from Ekkwill Waterlife Resources (Gibsonton, FL) were used. Fish were maintained at 26–28ºC on a 14-hour light and 10-hour dark cycle in a flow-through, dechlorinated water system at the Aquatic Animal Facility of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Children’s Environmental Health Sciences Center. All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Animal Care and Use Committee. Zebrafish were bred in 2-L plastic aquaria with a 1/8” nylon mesh false bottom to protect fertilized eggs from being consumed by the adults. Eggs were collected ≤ 2 hours post fertilization (hpf), counted, and placed into metal-free, glass culture dishes (100 mm diameter × 50 mm depth; N = 100 eggs/dish) containing an embryo development medium (each liter contains 0.875 g NaCl, 0.038 g KCl, 0.120 g MgSO4, 0.021 g KH2PO4, and 0.006 g Na2HPO4)

2.3 Exposure Regimen

A stock solution of 1 mM PbCl2 was prepared at pH 2 until fully dissolved. Using 1.0 M KOH, pH was adjusted to 6.5. Eggs were rinsed twice in Pb2+-free medium (as determined by ICP-MS analysis) and transferred (N = 100 eggs/dish; <2 hpf) to a metal-free glass dish (100 mm diameter × 50 mm depth) containing 100 ml of medium with Pb2+ at 0, 10 or 30 nM. At 24 hpf, eggs were rinsed three times with Pb2+-free medium and placed in clean, metal-free glass dishes with Pb2+-free medium until tested. Visual response experiments used concentrations that extended the range of exposure levels to include 3 and 100 nM Pb2+.

2.4 Mechanosensory Response

Responses to directional stimuli are observed in fish larvae and, therefore, are a useful tool to assess neurotoxicity. Details for this behavioral assay are described in Weber (2006). Briefly, larvae (n = 10/exposure regimen/tap frequency; 7 days post fertilization [dpf]) were placed individually into a white plastic chamber (15 mm diam., 3 mm deep). The chamber was lit using a fiber optic cable (Solarc, Model LB-24; Welch Allyn, Inc., Skaneateles Falls, NY, USA) and was the only source of light in the room. A small fan forced air over the experimental apparatus to prevent temperature changes that would alter responses. After a 3-minute acclimation period, a solenoid was remotely activated to control for intensity and tap frequency (either 1 or 4 taps/sec, i.e., one stimulus every 1000 or 250 msec, respectively, with each tap lasting approximately 4 msec). The tap intensity used for these experiments was the lowest at which >90% of all control larvae responded. Larval motion was recorded at 1000 fps using a PCI1024 high-speed CCD video camera (Motion Engineering, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, USA). The following four measures were recorded: latency of reaction (elapsed time interval in msec between moment solenoid arm taps the chamber pin and the initiation of the startle response), Vmax (maximum turn velocity in body lengths [BL]/sec), time to reach Vmax (msec) and duration of escape swim (total time elapsed in msec from beginning of the startle response to the end of the escape swim, i.e., cessation of caudal tail movement).

Using FLOTE version 2.0 (Burgess et al. 2009), traces of the larval swim pattern were created for the 4 tap/sec trials to assess potential changes in locomotor activity as a function of developmental Pb2+ exposure in addition to calculating latency of reaction, Vmax, and duration of escape swim.

2.5 Visual Response

The behavioral apparatus follows previously published accounts (Weber et al. 2008; Li and Dowling 1997) as modified for testing adults and to allow for different drum speeds and directions. Briefly, individual fish grouped by exposure concentration (n = 12; 4 months old, 1.5–2.0 cm standard length) were placed into one of four opaque compartments (gray PVC bottom and white plastic walls) within a glass container. This design allowed each fish to view and react to a rotating black bar (see below) without behavioral influence from a neighboring fish. The glass container (10 cm diam., 5 cm depth) was suspended by brackets over a rotating drum of white PVC plastic (diam. 11 cm, depth 4 cm). On the drum, black electrical tape (1 cm width × 5 cm height) was used to create a mark for eliciting a startle response when it comes into the fish’s field of vision. Zebrafish adults typically react to the rotating black bar by either eliciting a C-start escape response or an avoidance maneuver. After a 5-minute low light acclimation time, the number of C-start reactions to the leading edge was recorded over a 5-minute period. Since there is a circadian rhythm to light sensitivity (Li and Dowling 1998), all experiments were performed from 1300–1500 h each day.

Zebrafish are able to see well under low light conditions. To assess potential visual deficits, very low light conditions (~60 μW/m2) were created using a white light diode attached to a 500 μm optical fiber distribution bundle inserted through a PVC collar. This assured even distribution of equal spectral integrity throughout the chamber. A visible wavelength photodiode suspended in the observation chamber was connected to a digital meter (Micronta® 22, Radio Shack, Ft. Worth, TX) which also manipulated light intensity. To allow the observer to monitor fish behaviors under these low light levels, a ring of infrared (IR) LEDs (960 nm) was also inserted into the same PVC collar. Fish do not see in IR wavelengths (Nawrocki et al. 1985). The IR intensity could also be manipulated remotely. To allow for observer monitoring, an IR-sensitive CCD camera (Sony Hyper HAD B&W Video Camera) recorded images that were stored on a remote computer to facilitate observations without disturbing the test fish. The drum speed was set at 10 rev/min. Data were analyzed for total number of reactions/5 min using Pinnacle Studio Quick Start version 9.1 (Brothersoft.com) software.

2.6 Statistical Analyses

After video images from larval responses to the mechanosensory stimuli were analyzed using FLOTE v2.0 (Burgess et al. 2009), data were subjected to repeated measures ANOVA to compare responses at each stimulus within each trial (within subject factor = stimulus time; measures = latency of reaction, Vmax, time to reach Vmax and duration of escape swim; between subject factor = Pb2+ concentration). Repeated measures tests required no missing cells in the data spreadsheet. Therefore, non-responses were treated in the following manner: since the solenoid arm retracted at approx. 25 msec and occasionally induced a larval response, non-responders were given a value of 25 msec for both latency and time to reach Vmax. Capping these variables at a specific value effectively raised the threshold for showing statistical significance. Since a non-responder did not move, those cells in the data spreadsheet for Vmax (BL/sec) and duration of escape swim (msec) were given the value of “0”, i.e., no movement. Bonferroni intervals were used for multiple comparison tests over each stimulus time for the effect of exposure concentrations. Fisher’s Exact Test (2 × 3 contingency table; responders vs. non-responders × treatment group) was used to determine significance of exposure regimen effects at each stimulus time per trial. Level of significance for all statistical analyses was set at α = 0.05.

Data for the visual response data and ICP-MS analyses were subjected to a one-way ANOVA for effect of Pb2+ concentration. Level of significance was set at α = 0.05.

All statistical analyses and data presentations were accomplished using SPSS 13 software (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY).

3. RESULTS

3.1 Pb2+ Uptake

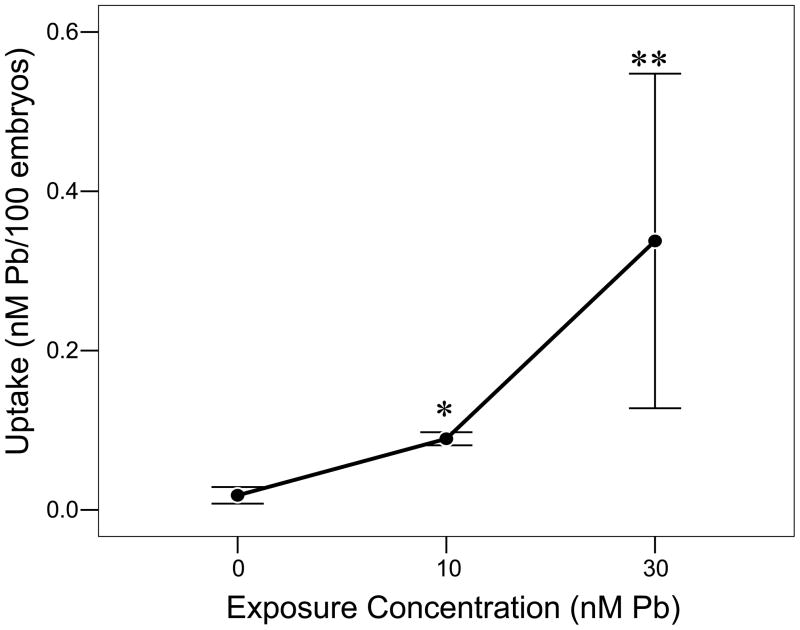

The uptake of Pb2+ by zebrafish embryos during the first 24 hpf was directly dependent upon the exposure concentrations, i.e., higher concentrations of Pb2+ in the exposure medium corresponded to greater Pb2+ in the 24 h-old embryo (Fig. 1; ANOVA, P < 0.01, F9,97, df = 2; Pearson’s coefficient of correlation, r2 = 0.836). Each exposure concentration was significantly different in the level of Pb2+ in the embryos (P < 0.05). There was no detectable Pb2+ in the larvae used for these tests (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Concentration-dependent uptake of Pb2+ in whole embryo during 2–24 hours post fertilization (n = 100 embryos/sample; 3 samples/concentration). Values = mean ± SE. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01

3.2 Mechanosensory Stimulus Response

3.2.1 Stimulus Frequency of 1 tap/sec

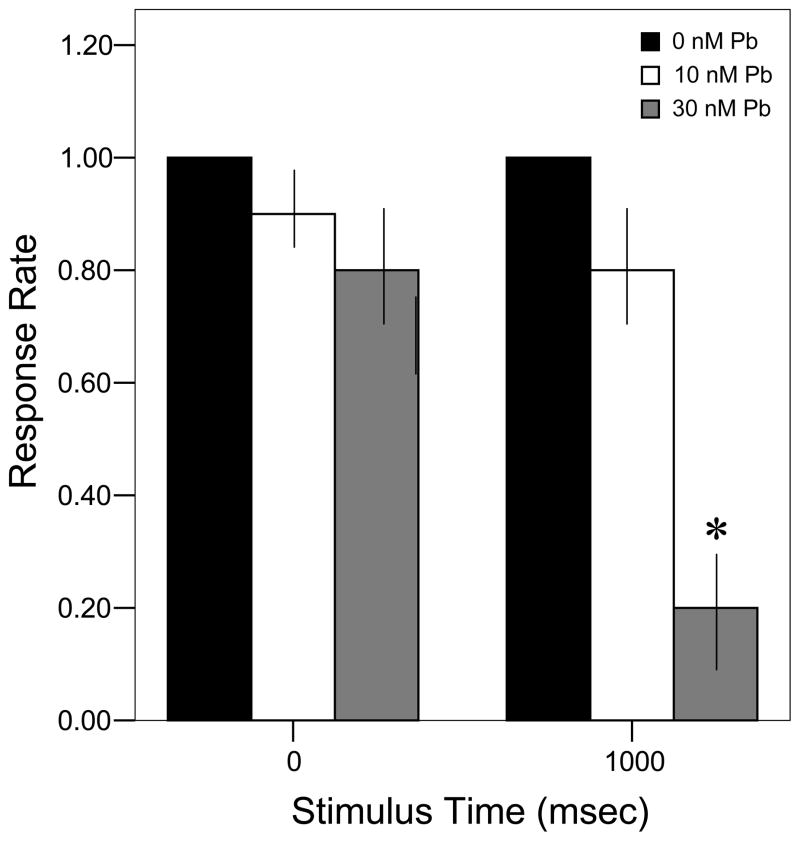

All control larvae (n = 10) responded to the stimulus at both the initial tap and the second tap 1000 msec later (Fig. 2). While fewer larvae developmentally exposed to 10 nM Pb2+ responded to the initial stimulus (n = 9), that number did not change over time. However, larvae from the 30 nM Pb2+ group demonstrated a large drop in the number responding to the second stimulus (n = 8 vs. 2, respectively; Fisher’s Exact Test, P < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Time- and concentration-dependent larval response to repeated stimuli at a frequency of 1 tap/sec. ▮= 0 nM Pb2+; ▯= 10 nM Pb2+;

= 30 nM Pb2+. Values = proportional number of larvae responding at each stimulus ± SD. Interval between each stimulus = 1000 msec. n = 10/exposure concentration. * = P < 0.0001 relative to control value at equivalent stimulus time.

= 30 nM Pb2+. Values = proportional number of larvae responding at each stimulus ± SD. Interval between each stimulus = 1000 msec. n = 10/exposure concentration. * = P < 0.0001 relative to control value at equivalent stimulus time.

Mean response latency

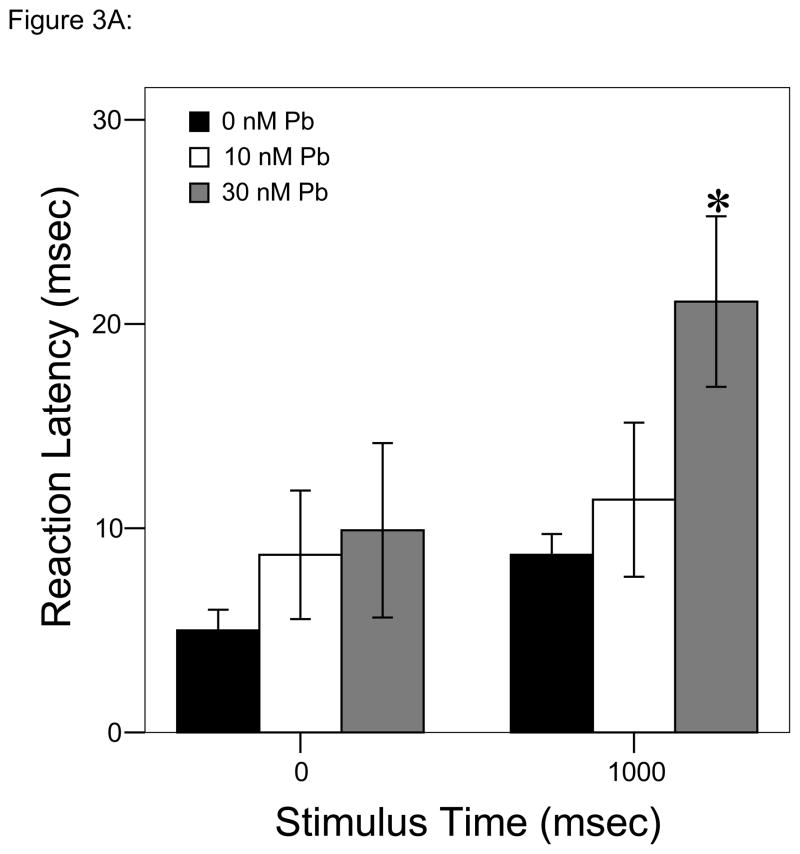

Analyses over time using repeated measures ANOVA to account for multiple stimuli/trial resulted in significant differences as a function of Pb2+ concentration (P < 0.05; Fig. 3A) with longer reaction times to the second stimulus in larvae developmentally exposed to 30 nM Pb2+ vs. either of the other two exposure groups.

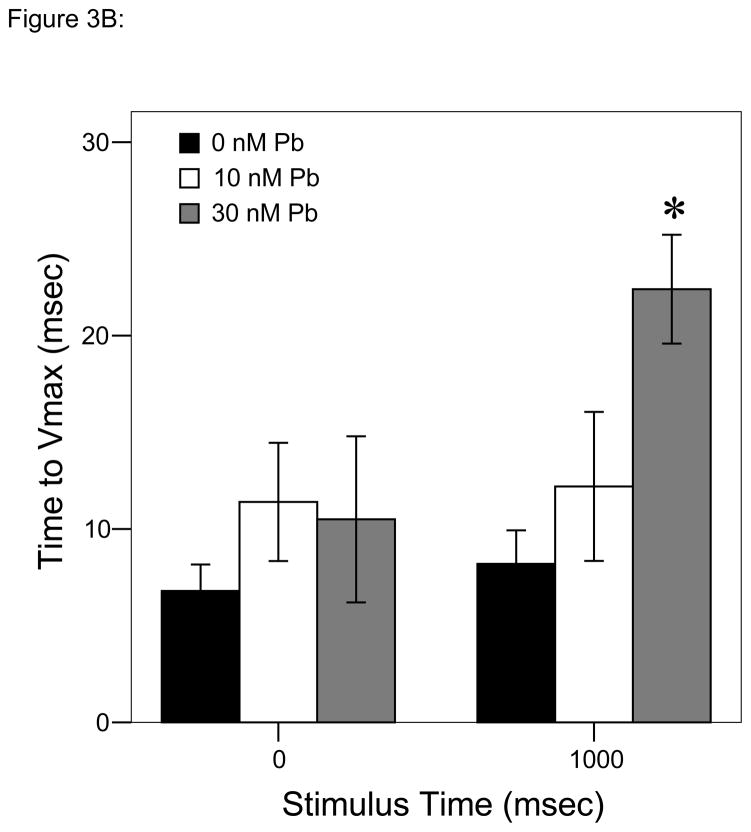

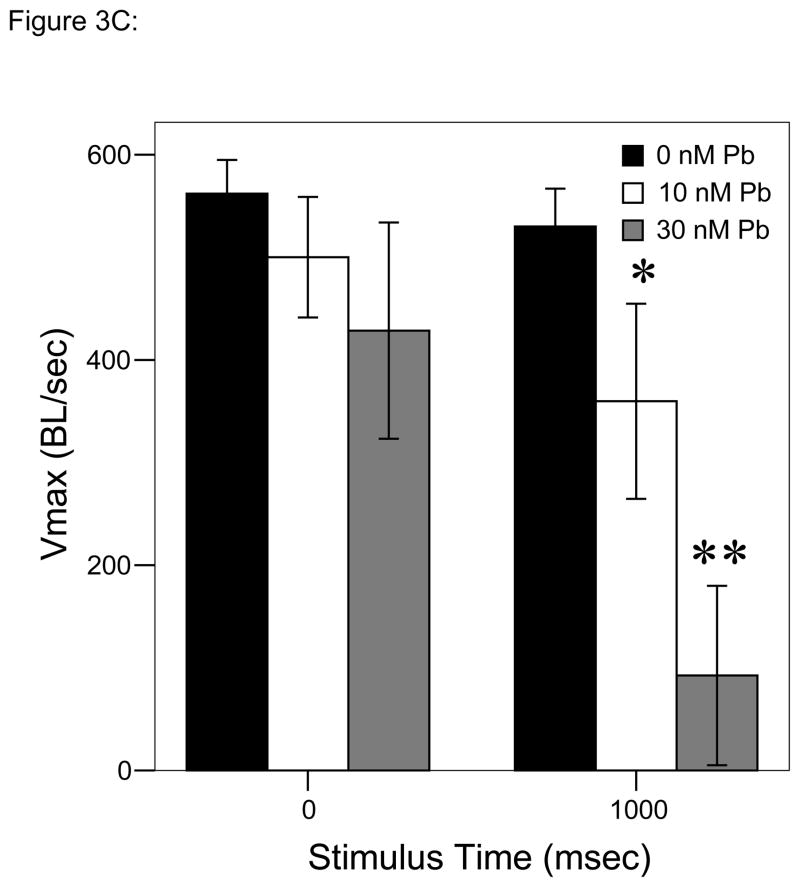

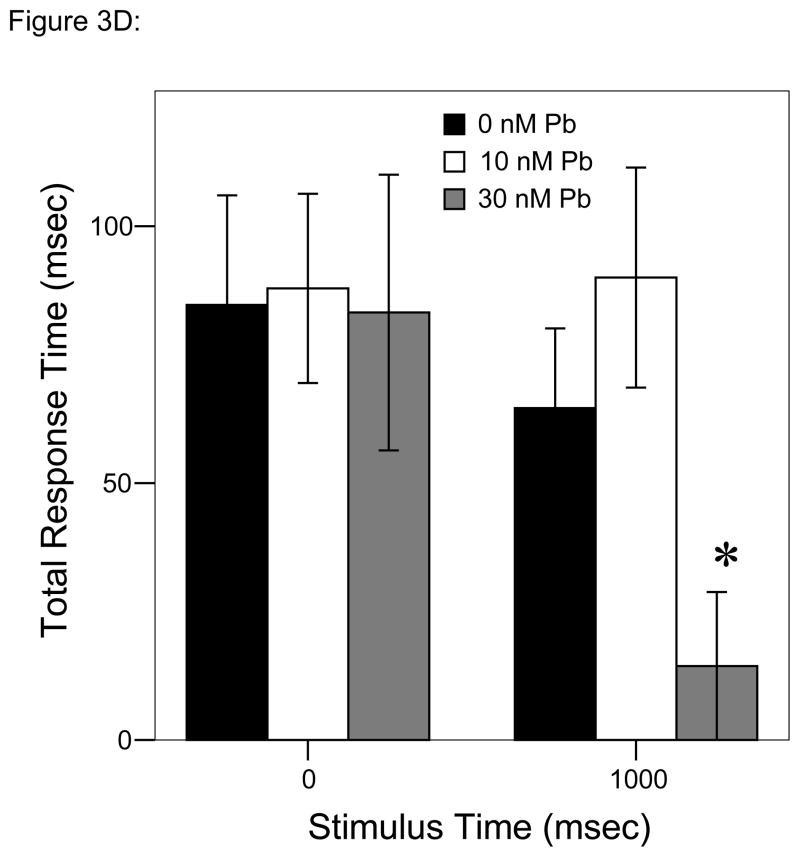

Figure 3.

Responses to each stimulus at a frequency of 1 tap/sec. ▮= 0 nM Pb2+; ▯= 10 nM Pb2+;

= 30 nM Pb2+. A. Time (msec) to initial response (reaction latency); B. Time (msec) to reach maximum head turning velocity (Vmax); C. Vmax (body lengths/sec); D. Duration (msec) of response (startle response + escape swim). Values = mean ± SE. Interval between each stimulus = 1000 msec. n = 10/exposure concentration. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P < 0.001 relative to control value at equivalent stimulus time.

= 30 nM Pb2+. A. Time (msec) to initial response (reaction latency); B. Time (msec) to reach maximum head turning velocity (Vmax); C. Vmax (body lengths/sec); D. Duration (msec) of response (startle response + escape swim). Values = mean ± SE. Interval between each stimulus = 1000 msec. n = 10/exposure concentration. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P < 0.001 relative to control value at equivalent stimulus time.

Mean time to reach Vmax

Analyses over time using repeated measures ANOVA to account for changes over recurring stimuli, however, resulted in highly significant differences as a function of Pb2+ concentration (P < 0.001; Fig. 3B); time to reach Vmax increased at a larger rate with the second stimulus in larvae developmentally exposed to 30 nM Pb2+ than larvae from either the control or 10 nM Pb2+ groups.

Mean Vmax

Analyses over time using repeated measures ANOVA to account for changes with each stimulus in the trial resulted in significant differences as a function of Pb2+ concentration (P < 0.01; Fig. 3C) with Vmax decreasing more with the second stimulus in larvae developmentally exposed to 30 nM Pb2+ vs. either of the other two exposure groups. In fact, the other two groups demonstrated no significant change between the first and second stimulus.

Mean duration of the startle and escape response

Differences at specific times of stimulation over the course of the 2-second trial were apparent (repeated measures ANOVA, P < 0.05; Fig. 3D) with total response time decreasing at a larger rate with the second stimulus in larvae developmentally exposed to 30 nM Pb2+ vs. either of the other two exposure groups.

3.2.2 Stimulus Frequency of 4 taps/sec

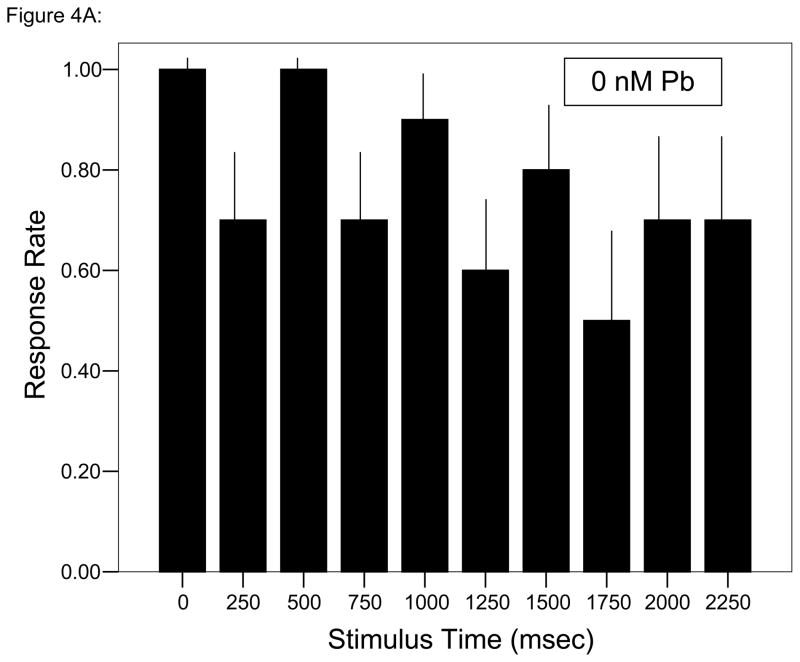

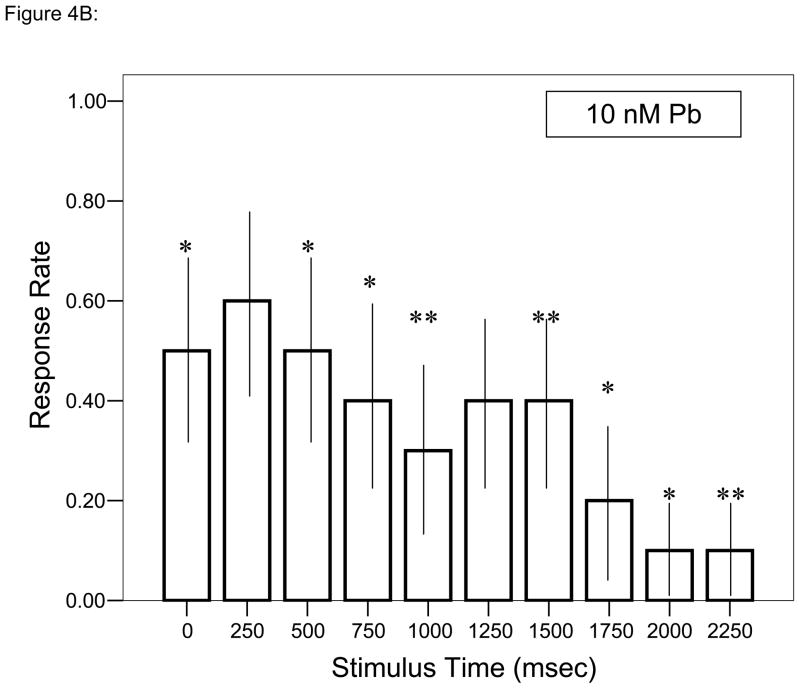

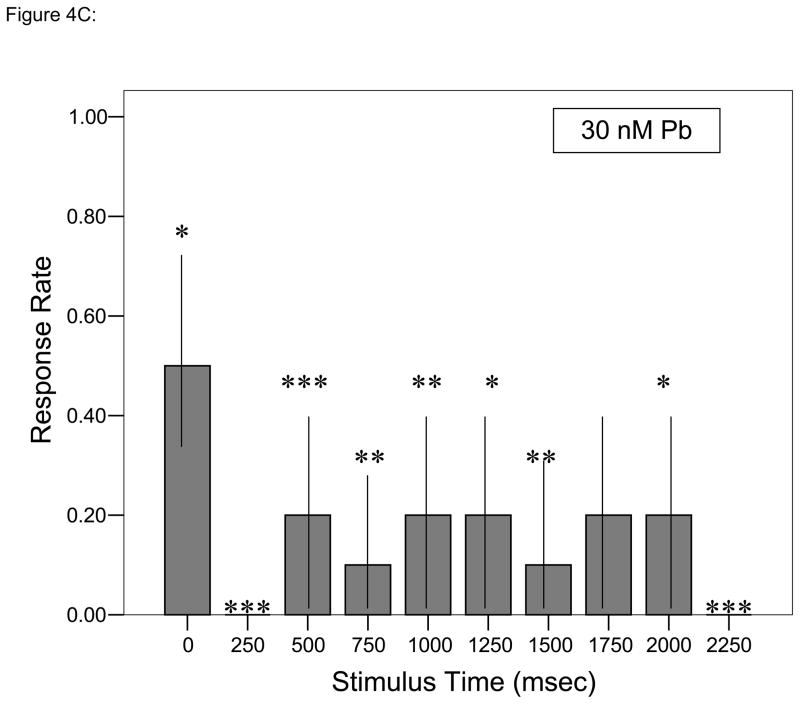

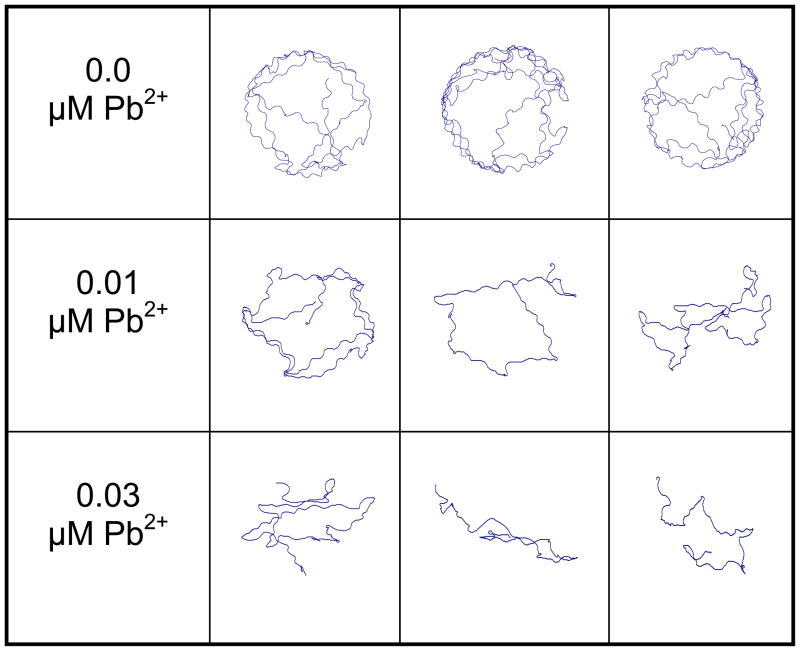

At all but one time points during each trial, ≥ 60% of control larvae responded to each stimulus (Fig. 4A). Decreased responsiveness relative to control larvae with the initial stimulus followed by further depressed responses was observed in larvae developmentally exposed to either concentration of Pb2+ (Figs. 4B, C; Fisher’s Exact Test, P < 0.05). Whereas control larvae tend to swim around the periphery of the startle test chamber, there was a progressive, concentration-dependent disruption of that pattern with Pb2+ exposure (Fig. 5). While larvae usually began each session at or near the chamber edge, there was less activity at the edge and a larger amount of movement along the chamber’s diameter, especially for the larvae exposed to 30 nM Pb2+.

Figure 4.

Time- and concentration-dependent larval response to repeated stimuli at a frequency of 4 taps/sec. A. ▮= 0 nM Pb2+; B. ▯= 10 nM Pb2+; C.

= 30 nM Pb2+. Values = proportional number of larvae responding at each tap stimulus ± SD. Interval between each stimulus = 250 msec. n = 10/exposure concentration. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P <0.005 relative to control value at equivalent stimulus time.

= 30 nM Pb2+. Values = proportional number of larvae responding at each tap stimulus ± SD. Interval between each stimulus = 250 msec. n = 10/exposure concentration. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P <0.005 relative to control value at equivalent stimulus time.

Figure 5.

Representative traces of movement of larvae developmentally exposed to 0, 10 or 30 nM Pb2+ in response to a directional stimulus at a frequency of 4 taps/sec for 2.25 seconds. Interval between each stimulus = 250 msec.

Mean response latency

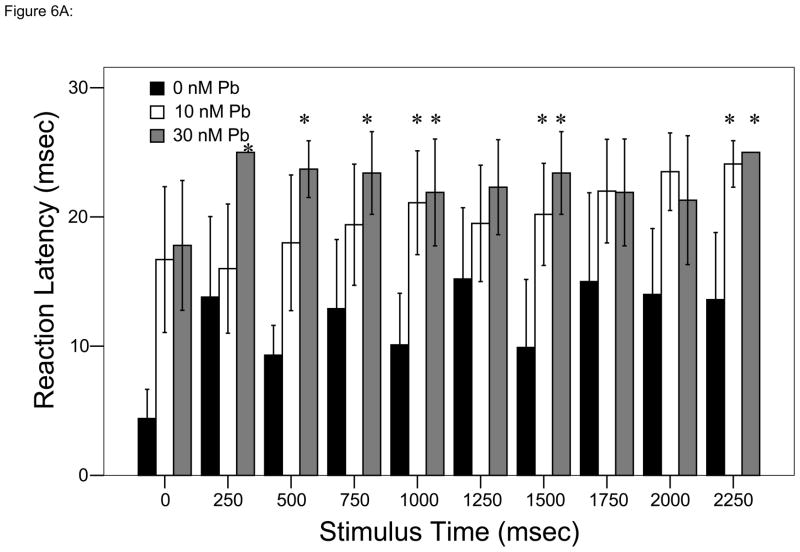

Analyses over time using repeated measures ANOVA demonstrate that while 10 and 30 nM Pb2+ are not significantly different, they were significantly slower to respond to stimuli than control larvae at some time points (Bonferroni multiple comparisons test, P < 0.005; Fig. 6A).

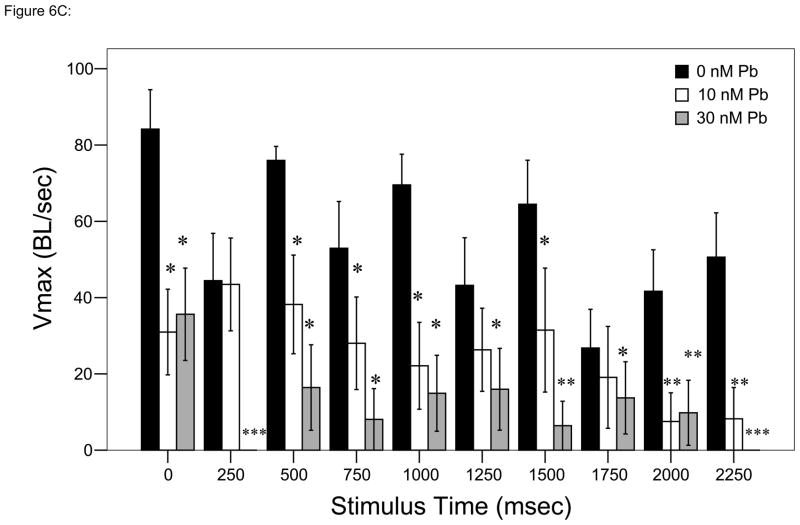

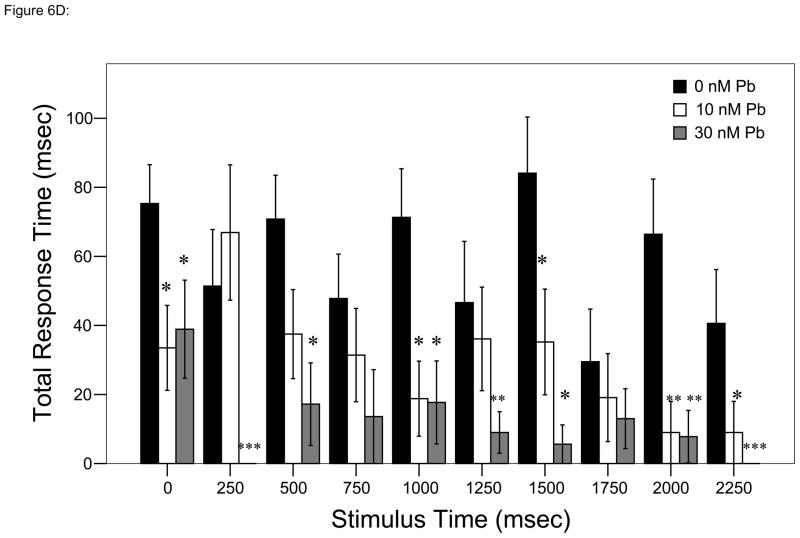

Figure 6.

Responses to each stimulus at a frequency of 4 taps/sec. ▮= 0 nM Pb2+; ▯= 10 nM Pb2+;

= 30 nM Pb2+. A. Time (msec) to initial response (reaction latency); B. Time (msec) to reach maximum head turning velocity (Vmax); C. Vmax (body lengths/sec); D. Duration (msec) of response (startle response + escape swim). Values = mean ± SE. Interval between each stimulus = 250 msec. n = 10/exposure concentration. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P <0.005 relative to control value at equivalent stimulus time.

= 30 nM Pb2+. A. Time (msec) to initial response (reaction latency); B. Time (msec) to reach maximum head turning velocity (Vmax); C. Vmax (body lengths/sec); D. Duration (msec) of response (startle response + escape swim). Values = mean ± SE. Interval between each stimulus = 250 msec. n = 10/exposure concentration. * = P < 0.05; ** = P < 0.01; *** = P <0.005 relative to control value at equivalent stimulus time.

Mean time to reach Vmax

Using repeated measures ANOVA resulted in significant differences at some time points only between the 0 and 30 nM Pb2+ groups (Bonferroni multiple comparisons test, P < 0.05; Fig. 6B), i.e., there no significant differences between 0 and 10 nM Pb2+ groups.

Mean Vmax

Analyses over time using repeated measures ANOVA resulted in significant differences between control and either Pb2+ exposure group at specific time points (Bonferroni multiple comparisons test, P < 0.05; Fig. 6C).

Mean duration of the startle and escape response

Differences at specific times of stimulation over the course of the 2-second trial were apparent (repeated measures ANOVA, P < 0.05) There were no significant differences between either Pb2+ exposure concentration at any time point (Bonferroni multiple comparisons test, P < 0.05; Fig. 6D).

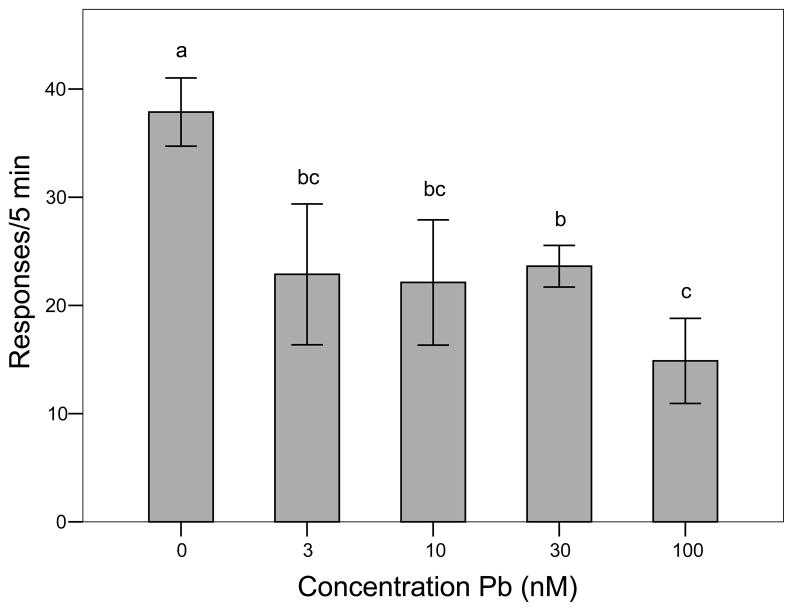

3.3 Visual Startle Response

At very low levels of developmental Pb2+ (3 nM) exposure, there was a significant reduction in reaction to the rotating black bar (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test, P < 0.05; Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of developmental Pb2+ exposure on the adult expression of visual responses to a rotating black bar (10 revolutions/min) under low light conditions (N = 12/exposure concentration). Bars (mean ± SE) with different letters are statistically different from mean control response (ANOVA, P< 0.001, Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test, P < 0.05). Means with the same letter are not statistically different.

4. DISCUSSION

Developmental Pb2+ exposures caused changes in larval responses to a tapping stimulus. While the time required to initiate a response increased, maximum head turn velocity and duration of the escape swim decreased with increasing Pb2+ concentration. In addition, the number of larvae who failed to respond to a stimulus increased with Pb2+ concentration. These changes in behavioral response became more pronounced when the stimulus frequency increased from 1 to 4 taps/sec. Decreases in adult visual startle responses also demonstrated a concentration-dependent change.

The simple neural network of the startle response followed by an escape swim allows for a first-step examination of the relationship between Pb2+ neurotoxicity and behavioral outcomes. This study used two sensorimotor networks in a zebrafish, mechanosensory and visual, to assess the effect of very low-level, developmental Pb2+ exposure on larval startle responses. Exposure regimens were within the period in which embryonic motor circuits form (Thomas et al. 2009).

The Pb2+ levels used in this study are three orders of magnitude lower than that reported in very low-level Pb2+ exposure mammalian studies that, in some studies, extended beyond gestation into early postnatal stages (e.g., Fortune and Lurie 2009). Metal cation uptake in fish eggs often becomes bound in the perivitelline fluid of the zona radiata once the egg has undergone water hardening after 24 hpf (Rombough 1985). Since only 50% of the Pb2+ during waterborne exposures actually enters the embryo due to the binding capacity of the perivitelline fluid (Zhang et al. in press), we actually observed behavioral effects at embryo Pb2+ concentrations that were at or below detection by ICP-MS.

Several research groups have tracked the swim pattern of fish larvae exposed to a range of organic chemicals (Irons et al. 2010 [neuroactive drugs]; Jin et al. 2010 [bifenthrin]; Powers et al. 2010 [Ag+]; Winter et al. 2008 [pharmaceuticals]; Levin et al. 2004 [chlorpyrifos]). These experiments, however, used video recording speeds that were sufficient only for tracking general locomotor activity without external physical stressors that would initiate a startle response. This paper describes results based on high-speed videography to view the series of fast movements that constitute the startle and escape behaviors in response to repeated directional stimuli. This study examined the effects of a chemical stressor, Pb2+, on two forms of sensory perception (mechanosensory [lateral line system] and visual [retinal neurons]) and the startle response they trigger. The startle, or C-start, response represents the behavioral outcome of the integration of sensory neurons (sensory perception), Mauthner cells (information integration), interneurons and neuromuscular junctions (neuromuscular activation) in which there is a rapid movement away from the source of the stimulus, resulting in the body flexing in a C-shape before it straightens out to escape.

Our results cannot be specifically associated with any one aspect of the startle response neural pathway because these data do not differentiate between Pb2+-induced impaired detection (sensory), altered integration (M-cell), impaired response (neuromuscular) or increased fatigue (respiratory/muscular). Still, these data are consistent with several possible mechanisms and it is likely that multiple sites of Pb2+ neurotoxicity exist. First, the lateral line system in fishes and the neuromasts that constitute the sensory cells of that system are highly sensitive to metal exposure (Froehlicher et al. 2009). One explanation for the delayed response evident in the Pb2+-exposed larvae (Fig. 3A) is an increase in the sensory threshold of the lateral line neuromasts, as observed in frog and rat retinal cells exposed to Pb2+ (Fox et al. 2008; Fox et al. 1991; Fox and Sillman 1979). Second, depressed neuronal function also may have occurred in the descending interneurons that connect the M-cell to the lateral trunk muscles. At a stimulus frequency of 1 tap/sec, both the maximum head turn velocity (Vmax) and time to reach Vmax (Figs. 3B, C) was significantly different at the higher concentration level of 30 nM Pb2+. These differences became more pronounced for all exposure concentrations at the higher stimulus frequency of 4 taps/sec (Figs. 6B, C). At this higher stimulus frequency, a progressive degeneration in escape swim activity was observed (Fig. 5). Rather than a majority of the swimming activity occurring at the chamber periphery, there was progressive, concentration-dependent switch to activity centrally located, if the larvae responded at all to the stimulus. Third, there are four major neurotransmitter and neurotransmitter receptor sites in the piscine M-cell: glutamate, glycine, γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) and serotonin (5-HT). These can be found in both the developing embryo and the adult fish (Patten and Ali 2007; Rigo and Legendre 2006; McLean and Fetcho 2004; Hatta et al. 2001; Triller et al. 1997; Diamond 1968) and all are affected by Pb2+ (Fortune and Lurie 2009; Xing et al. 2009; Fitsanakis and Aschner 2005; Spieler et al. 1995; Weber et al. 1991). Fourth, while no data exist for the effect of developmental Pb2+ on depolarization in fish neurons, it has been shown that post hatch exposures inhibit contraction of single muscle fibers and suppress fast and slow Ca2+ currents in crayfish (Zacharová et al. 1993). These observations correspond to the decrease in escape swim time duration (Figs. 3D, 6D) and the compressed track patterns in zebrafish larvae developmentally exposed to Pb2+.

Visual stimuli, as used in this study, elicit a Mauthner cell-initiated startle response similar to that observed with mechanosensory stimulation (Eaton et al. 1977). In the experiments reported in this study, the ability to detect contrast (a black bar against a white background) is an important first step to initiate the visual startle response. Changes in the sensitivity to such contrasts and the resultant alterations in behavioral responses are a useful method to assess the effects of neurotoxicant exposures. A change of response suggests that the functionality of either the ON- or OFF-center receptive fields has been compromised. The optomotor responses to visual stimuli used in these experiments depend upon the sum of electrical signals transmitted from the circular receptive fields of the bipolar and amicrine cells to the ganglion and then through the optic nerve to the optic tectum. The formation of these retinal neurons occurs during the period of developmental Pb2+ exposure (0–24 hpf) used in this study (Schmitt and Dowling 1999, 1994) which is responsible for raising the threshold of activation in frog rod cells (Fox et al. 1991). Similarly, a change in sensory threshold may have occurred in the visual startle response test in adult zebrafish developmentally exposed to Pb2+ (Fig. 7) due, in part, to changes in sensory perception of borders. Additional effects on information integration may be occurring at higher brain centers, since Pb2+ reduces dopamine levels in the rainbow trout optic tectum (Rademacher et al. 2001).

5. CONCLUSIONS

Low-level developmental Pb2+ exposures induce behavioral disruptions in mechanosensory startle responses of larval zebrafish. These altered behaviors manifest themselves as disruptions in ability to respond to a stimulus, as well as the time required for responding, maximum head turn velocity and duration of escape swim. Furthermore, the pattern of the escape swim is changed in larvae from Pb2+-exposed embryos. Rather than swimming along the test chamber periphery, those larvae that do respond to the stimuli, spend most of their escape swim time along the diameter of the test chamber. In addition, these same exposure regimens have the capacity to cause long-term effects in startle behaviors, e.g., visual responses in adult zebrafish, even at very low developmental Pb2+ concentrations.

Highlights.

Low-level developmental Pb2+ exposures induce behavioral disruptions in mechanosensory startle responses of larval zebrafish. These altered behaviors manifest themselves as disruptions in ability to respond to a stimulus, as well as the time required for responding, maximum head turn velocity and duration of escape swim. Furthermore, the pattern of the escape swim is changed in larvae from Pb2+-exposed embryos. Rather than swimming along the test chamber periphery, those larvae that do respond to the stimuli, spend most of their escape swim time along the diameter of the test chamber. In addition, these same exposure regimens have the capacity to cause long-term effects in startle behaviors, e.g., visual responses in adult zebrafish, even at very low developmental Pb2+ concentrations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Harold Burgess (NIH-Bethesda) for image analysis advice and Kurt Svoboda (UW-Milwaukee) for suggestions for improvements to the manuscript. Research supported by an NIEHS grant (ES01484) to David Petering (UW-Milwaukee).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Basha R, Reddy GR. Developmental exposure to lead and late life abnormalities of nervous system. Indian J Exp Biol. 2010;48:636–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buekers J, Redekerm ES, Smoldersm E. Lead toxicity to wildlife: derivation of a critical blood concentration for wildlife monitoring based on literature data. Sci Total Environ. 2009;15:3431–3438. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn TL, Parsons PJ, Kao E, Dietert RR. Exposure to lead during critical windows of embryonic development: differential immunotoxic outcome based on stage of exposure and gender. Toxico Sci. 2001;64:57–66. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/64.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess HA, Johnson SL, Granato M. Unidirectional startle responses and disrupted left-right co-ordination of motor behaviors in robo3 mutant zebrafish. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:500–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvan MJ, III, Loucks E, Weber DN, Williams FE. Ethanol effects on the developing zebrafish: neurobehavior and skeletal morphogenesis. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26:757–768. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory-Slechta DA. Relationships between lead-induced learning impairments and changes in dopaminergic, cholinergic, and glutamatergic neurotransmitter system functions. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995a;35:391–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.002135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory-Slechta DA, Pokora MJ. Lead-induced changes in muscarinic cholinergic sensitivity. Neurotoxicol. 1995b;16:337–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa LG, Aschner M, Vitalone A, Syversen T, Soldin OP. Developmental neuropathology of environmental agents. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:87–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearth RK, Hiney JK, Srivastava V, Dees LW, Bratton GR. Low level lead (Pb) exposure during gestation and lactation: assessment of effects on pubertal development in Fisher 344 and Sprague-Dawley female rats. Life Sci. 2004;74:1139–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearth RK, Hiney JK, Srivastava V, Burdick SB, Bratton GR, Dees WL. Effects of lead (Pb) exposure during gestation and lactation on female pubertal development in the rat. Reprod Toxicol. 2002;16:343–352. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(02)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoto P, Flore G, Ibba A, Fratta W, Pani L. Lead intoxication during intrauterine life and lactation but not during adulthood reduces nucleus accumbens dopamine release as studied by brain microdialysis. Toxicol Lett. 2001;121:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(01)00336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond J. The activation and distribution of GABA and L-glutamate receptors on goldfish Mauthner neurons: an analysis of dendritic remote inhibition. J Physiol. 1968;194:669–723. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich KN, Krafft KM, Pearson DT, Bornschein RL, Hammond PB, Succop PA. Postnatal lead exposure and early sensorimotor development. Environ Res. 1985;38:130–136. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(85)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton RC, Bombardieri RA, Meyer DL. The Mauthner-initiated startle response in teleost fish. J Exp Biol. 1977;66:65–81. doi: 10.1242/jeb.66.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi M, Taherianfard M. Concentration of four heavy metals (cadmium, lead, mercury, and arsenic) in organs of two cyprinid fish (Cyprinus carpio and Capoeta sp.) from the Kor River (Iran) Environ Monit Assess. 2010;16:575–585. doi: 10.1007/s10661-009-1135-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitsanakis VA, Aschner M. The importance of glutamate, glycine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid transport and regulation in manganese, mercury and lead neurotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;204:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortune T, Lurie DI. Chronic low-level lead exposure affects the monoaminergic system in the mouse superior olivary complex. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513:542–558. doi: 10.1002/cne.21978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox DA, Kala SV, Hamilton WR, Johnson JE, O’Callaghan JP. Low-level human equivalent gestational lead exposure produces supernormal scotopic electroretinograms, increased retinal neurogenesis, and decreased retinal dopamine utilization in rats. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:618–625. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11268. Erratum in: Environ Health Perspect 2008, 116: A241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox DA, Katz LM, Farber DB. Low level developmental lead exposure decreases the sensitivity, amplitude and temporal resolution of rods. Neurotoxicology. 1991;12:641–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox DA, Silman AJ. Heavy metals affect rod, but not cone, photoreceptors. Science. 1979;206:78–80. doi: 10.1126/science.314667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GA. Tinkering with the tinkerer: pollution versus evolution. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103 (Suppl 4):93–100. doi: 10.1289/ehp.103-1519277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlicher M, Liedtke A, Groh KJ, Neuhauss SC, Segner H, Eggen RI. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) neuromast: promising biological endpoint linking developmental and toxicological studies. Aquat Toxicol. 2009;95:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta K, Ankri N, Faber DS, Korn H. Slow inhibitory potentials in the teleost Mauthner cell. Neurosci. 2001;103:561–579. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00570-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinck JE, Schmitt CJ, Blazer VS, Denslow ND, Bartish TM, Anderson PJ, Coyle JJ, Gail M, Dethloff GM, Tillitt DE. Environmental contaminants and biomarker responses in fish from the Columbia River and its tributaries: Spatial and temporal trends. Sci Tot Environ. 2006;366:549–578. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iavicoli I, Fontana L, Bergamaschi A. The effects of metals as endocrine disruptors. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2009;12:206–223. doi: 10.1080/10937400902902062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irons TD, MacPhail RC, Hunter DL, Padilla S. Acute neuroactive drug exposures alter locomotor activity in larval zebrafish. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2010;32:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M, Zhang Y, Ye J, Huang C, Zhao M, Liu W. Dual enantioselective effect of the insecticide bifenthrin on locomotor behavior and development in embryonic-larval zebrafish. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2010;29:1561–1567. doi: 10.1002/etc.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann AC, McGlothan JL, Guilarte TR. Developmental lead exposure causes spatial learning deficits in adult rats. Neurosci Lett. 1997;233:101–114. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00633-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahnsteiner F. The sensitivity and reproducibility of the zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryo test for the screening of wastewater quality and for testing the toxicity of chemicals. Altern Lab Anim. 2008;36:299–311. doi: 10.1177/026119290803600308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leasure JL, Giddabasappa A, Chaney S, Johnson JE, Jr, Pothakos K, Lau YS, Fox DA. Low-level human equivalent gestational lead exposure produces sex-specific motor and coordination abnormalities and late-onset obesity in year-old mice. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:355–361. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque HM, Dorval J, Hontela A, Van Der Kraak GJ, Campbell PG. Hormonal, morphological, and physiological responses of yellow perch (Perca flavescens) to chronic environmental metal exposures. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2003;11:657–676. doi: 10.1080/15287390309353773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Swain HA, Donerly S, Linney E. Developmental chlorpyrifos effects on hatchling zebrafish swimming behavior. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26:719–723. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Dowling JE. Zebrafish visual sensitivity is regulated by a circadian clock, Vis. Neurosci. 1998;15:851–857. doi: 10.1017/s0952523898155050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Dowling JE. A dominant form of inherited retinal degeneration caused by non-photoreceptor cell-specific mutation, Proc. Nat Acad Sci. 1997;94:11645–11650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean DL, Fetcho JR. Relationship of tyrosine hydroxylase and serotonin immunoreactivity to sensorimotor circuitry in larval zebrafish. J Comp Neurol. 2004;480:57–71. doi: 10.1002/cne.20281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira EG, Vassilieff I, Vassilieff VS. Developmental lead exposure: behavioral alterations in the short and long term. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23:489–495. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RE, Garavan H, Smith EG, Driscoll LL, Levitsky DA, Strupp BJ. Early lead exposure produces lasting changes in sustained attention, response initiation, and reactivity to errors. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23:519–531. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller KA, Snyder-Conn E, Bertram M. Water Quality and Metal and Metalloid Contaminants in Sediments and Fish of Koyukuk, Nowitna, and the Northern Unit of Innoko National Wildlife Refuges, Alaska, 1991. Natl Tech Info Serv 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki L, BreMiller R, Streisinger G, Kaplan M. Larval and adult visual pigments of the zebrafish. Brachydanio rerio, Vision Res. 1985;25:1569–1576. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(85)90127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal AP, Worley PF, Guilarte TR. Lead exposure during synaptogenesis alters NMDA receptor targeting via NMDA receptor inhibition. Neurotoxicol. 2011;32:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberto A, Marks N, Evans HL, Guidotti A. Lead (Pb+2) promotes apoptosis in newborn rat cerebellar neurons: pathological implications. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:435–442. doi: 10.1163/2211730x96x00234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten SA, Ali DW. AMPA receptors associated with zebrafish Mauthner cells switch subunits during development. J Physiol. 2007;581:1043–1056. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.129999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers CM, Yen J, Linney EA, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Silver exposure in developing zebrafish (Danio rerio): persistent effects on larval behavior and survival. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2010;32:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher DJ, Steinpreis RE, Weber DN. Short-term exposure to dietary Pb and/or DMSA affects dopamine and dopamine metabolite levels in the medulla, optic tectum, and cerebellum of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:199–207. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00597-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy GR, Devi BC, Chetty CS. Developmental lead neurotoxicity: alterations in brain cholinergic system. Neurotoxicol. 2007;28:402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter LW, Anderson GE, Laskey JW, Cahill DF. Developmental and behavioral changes in the rat during chronic exposure to lead. Environ Health Perspect. 1975;12:119–123. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7512119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigo JM, Legendre P. Frequency-dependent modulation of glycine receptor activation recorded from the zebrafish larvae hindbrain. Neurosci. 2006;140:389–402. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombough PJ. The influence of the zona radiata on the toxicities of zinc, lead, mercury, copper and silver ions to embryos of steelhead trout Salmo gairdneri. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 1985;82:115–117. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(85)90216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt FA, Dowling JE. Early eye morphogenesis in the zebrafish, Brachydanio rerio. J Comp Neurol. 1994;344:532–542. doi: 10.1002/cne.903440404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt FA, Dowling JE. Early retinal development in the zebrafish, Danio rerio: light and electron microscopic analyses. J Comp Neurol. 1999;404:515–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt CJ, Brumbaugh WG, Linder GL, Hinck JE. A screening-level assessment of lead, cadmium, and zinc in fish and crayfish from Northeastern Oklahoma, USA. Environ Geochem Health. 2006;28:445–471. doi: 10.1007/s10653-006-9050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spieler RE, Russo AC, Weber DN. Waterborne lead affects circadian variations of brain neurotransmitters in fathead minnows. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1995;55:412–418. doi: 10.1007/BF00206680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickler-Shaw S, Taylor DH. Lead inhibits acquisition and retention learning in bullfrog tadpoles. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1991;13:167–173. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(91)90007-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Zhao ZY, Hu J, Zhou XL. Potential association of lead exposure during early development of mice with alteration of hippocampus nitric oxide levels and learning memory. Biomed Environ Sci. 2005;18:375–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LT, Welsh L, Galvez F, Svoboda KR. Acute nicotine exposure and modulation of a spinal motor circuit in embryonic zebrafish. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;239:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triller A, Rostaing P, Korn H, Legendre P. Morphofunctional evidence for mature synaptic contacts on the Mauthner cell of 52-hour-old zebrafish larvae. Neurosci. 1997;80:133–145. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber DN, Russo A, Seale DB, Spieler RE. Waterborne lead affects feeding abilities and neurotransmitter levels of juvenile fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) Aquat Toxicol. 1991;21:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Weber DN. Exposure to sublethal levels of waterborne lead alters reproductive behavior patterns in fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) Neurotoxicol. 1993;14:347–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber DN, Dingel WM, Panos JJ, Steinpreis RE. Alterations in neurobehavioral responses in fishes exposed to lead and lead-chelating agents. Amer Zool. 1997;37:354–362. [Google Scholar]

- Weber DN. Dose-dependent effects of developmental mercury exposure on C-start escape responses of larval zebrafish Danio rerio. J Fish Biol. 2006;69:75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Weber DN, Connaughton VP, Dellinger JA, Klemer D, Udvadia A, Carvan MJ., III Selenomethionine reduces visual deficits due to developmental methylmercury exposures. Physiol Behav. 2008;93:250–260. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber DN, Spieler RE. Behavioral mechanisms of metal toxicity in fishes. In: Malins DC, Ostrander GK, editors. Aquatic Toxicology: Molecular, Biochemical, and Cellular Perspectives. Lewis Publishers; Boca Raton, FL: 1994. pp. 421–467. [Google Scholar]

- Winter MJ, Redfern WS, Hayfield AJ, Owen SF, Valentin JP, Hutchinson TH. Validation of a larval zebrafish locomotor assay for assessing the seizure liability of early-stage development drugs. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2008;57:176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing XJ, Rui Q, Du M, Wang DY. Exposure to lead and mercury in young larvae induces more severe deficits in neuronal survival and synaptic function than in adult nematodes. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2009;56:732–741. doi: 10.1007/s00244-009-9307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Ma Y, Ni L, Zhao S, Li L, Zhang J, Fan M, Liang C, Cao J, Xu L. Lead exposure through gestation-only caused long-term learning/memory deficits in young adult offspring. Exp Neurol. 2003;184:489–495. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharová D, Hencek M, Pavelková J, Lipská E. The effect of Pb2+ ions on calcium currents and contractility in single muscle fibres of the crayfish. Gen Physiol Biophys. 1993;12:183–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Peterson SM, Weber GJ, Zhu X, Zheng W, Freeman JL. Decreased axonal density and altered expression profiles of axonal guidance genes underlying lead (Pb) neurodevelopmental toxicity at early embryonic stages in the zebrafish. Neurotox Teratol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.07.010. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]