Abstract

Osteoclastogenesis is associated with aging and various age-related inflammatory chronic diseases, including cancer. Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) ligand (RANKL), a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily, has been implicated as a major mediator of bone resorption, suggesting that agents that can suppress RANKL signaling might inhibit osteoclastogenesis, a process closely linked to bone resorption. We therefore investigated whether butein, a tetrahydroxychalcone, could inhibit RANKL signaling and suppress osteoclastogenesis induced by RANKL or tumor cells. We found that human multiple myeloma cells (MM.1S and U266), breast tumor cells (MDA-MB-231), and prostate tumor cells (PC-3) induced differentiation of macrophages to osteoclasts, as indicated by TRAP-positive cells, and that butein suppressed this process. The chalcone also suppressed the expression of RANKL by the tumor cells. We further found that butein suppressed RANKL-induced NF-κB activation and that this suppression correlated with the inhibition of IκBα kinase and suppression of phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα, an inhibitor of NF-κB. Finally, butein also suppressed the RANKL-induced differentiation of macrophages to osteoclasts in a dose-dependent and time-dependent manner. Collectively, our results indicate that butein suppresses the osteoclastogenesis induced by tumor cells and by RANKL, by suppression of the NF-κB activation pathway.

Keywords: Butein, RANKL, cancer, osteoclastogenesis, NF-κB

Introduction

Bony lesions that develop secondarily to malignancies are a major clinical problem, affecting over 350,000 patients in the United States annually. Multiple myeloma, the second most common hematologic malignancy, is a tumor of terminally differentiated plasma cells that home to and expand in the bone marrow. Approximately 16,000 new cases of multiple myeloma are diagnosed every year, accounting for an estimated 11,000 deaths in the United States. Multiple myeloma is the most common cancer to metastasize to bone, with up to 90% of patients developing bone lesions. In addition to multiple myeloma, solid tumors such as prostate, breast, and lung cancers also metastasize to bone 1. Approximately 75% of patients with advanced breast cancer or hormone-refractory prostate cancer as well as, 40% of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and carcinoma have and upto 95% of patients with multiple myeloma tumor metastasis to bone 1, 2. This metastasis of tumor cells to bone can be accompanied by intractable bone pain, fractures that occur either spontaneously or following trivial injury, and hypercalcemia with its attendant symptoms and signs and is thus associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Cancers induce marked deterioration of quality of life and the activity of daily living of patients. Thus the social and economic burden of this disease is progressively increasing. As a result the improved survival of patients with cancers by means of significant advances in primary cancer site control, much attention should be paid to cancer bone metastasis.

Receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) is member 11 of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily of cytokines, which plays a central role in the development and function of osteoclasts 3. Osteoclast activity is regulated by the differential expression of RANKL, its receptor RANK, and the decoy receptor osteoprotegerin (OPG) 4, 5. Within the bone microenvironment, RANKL is produced by bone marrow stromal cells and osteoblasts 4, 5. The interaction of RANKL with RANK on osteoclasts is essential for osteoclast formation, function, and survival 6. The activity of RANKL can be blocked by the decoy receptor OPG, which is secreted by many different cell types 7. The local ratio of RANKL/OPG ultimately determines the level of osteoclast activation, resulting in physiological bone resorption as part of normal bone turnover or in pathological osteolysis as observed with bone metastasis 8.

The above description thus suggests that agents that can inhibit the RANKL signaling pathway may have potential in treating bone loss. Therefore, in this current study we investigated whether the chalcone butein (3,4,2′,4′-tetrahydroxychalcone) can modulate RANKL-induced signaling and osteoclastogenesis. Butein is a polyphenol derived from numerous plants, including the stem bark of Indian marking nut (Semecarpus anacardium), the heartwood of the fragrant rosewood (Dalbergia odorifera), and the traditional Chinese and Tibetan medicinal herbs Caragana jubata and Rhus verniciflua 9. It has been established that butein can suppress proliferation in a wide variety of human tumor cells, including breast carcinoma 10, colon carcinoma 11, osteosarcoma 12, lymphoma13, acute myelogenous leukemia 14, melanoma 15, multiple myeloma 9, and hepatic satellite cells 16. This chalcone can suppress the NF-κB signaling pathway and also can inhibit constitutive and inducible STAT3 activation in several types of tumor cells 9, 17. The current report is based on the hypothesis that butein inhibits tumor cell-induced osteoclastogenesis. We also investigated whether butein can suppress RANKL signaling and RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. We found that butein can modulate expression of RANKL in tumor cells and can suppress the RANKL-induced NF-κB activation pathway through inhibition of IκBα kinase (IKK) and can inhibit osteoclastogenesis induced by RANKL and by tumor cells.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Butein (purity, ≥ 98%; Fig. 1A) was purchased from Alexis and prepared as a 50 mM solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then further diluted in cell culture medium. Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), DMEM/F12 medium, RPMI 1640 medium, fetal bovine serum, 0.4% trypan blue vital stain, and antibiotic-antimycotic mixture were obtained from Invitrogen. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to IκBα and TRAF6 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibody against phospho-IκBα (Ser32/36) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-IKKα, anti-IKKβ and anti-RANKL, and anti-RANK antibodies were kindly provided by Imgenex. Goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase conjugates were purchased from Bio-Rad. Antibody against β-actin and the leukocyte acid phosphatase kit (387-A) for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Protein A/G-agarose beads were obtained from Pierce. [γ-32P]ATP was purchased from MP Biomedicals.

Fig. 1.

Butein inhibits osteoclastogenesis induced by tumor cells. (A) Structure of butein. (B) RAW264.7 cells (5 × 103) were incubated in the presence of MM.1S cells (1 × 103), U266 cells (1 × 103), MDA-MB-231 cells (1 × 103) and PC-3 cells (1 × 103) for 24 hours, exposed to the indicated concentrations of butein for 5 days, and finally stained for TRAP expression. Multinucleated osteoclasts (i.e., those containing three nuclei) in cocultures were counted.

Cell lines

RAW264.7 cells (mouse macrophage), MDA-MB-231 cells (human breast adenocarcinoma), PC-3 cells (human prostate carcinoma), MM.1S cells (human multiple myeloma), and U266 cells (human multiple myeloma) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. RAW264.7 cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. This cell line is a well-established osteoclastogenic cell system that has been shown to express RANK and differentiate into functional TRAP-positive osteoclasts when cultured with soluble RANKL 18. Moreover, RANKL has been shown to activate NF-κB in RAW264.7 cells 19. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in DMEM; PC-3, MM.1S, and U266 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum. The above-mentioned cell lines were procured more than 6 months ago and have not been tested recently for authentication in our laboratory.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity of butein was evaluated using a modified tetrazolium salt MTT assay 20.

Osteoclast differentiation assay

RAW264.7 cells were cultured in 24-well dishes at a density of 5 ×103 per well and allowed to adhere overnight. The medium was then replaced, and the cells were treated with 5 nM RANKL for 5 days. All cell lines were subjected to TRAP staining using the leukocyte acid phosphatase kit (387-A).

Bone resorption pit assay

The effect of butein on bone resorption by pit formation assay was performed as described21.

Reverse transcription-PCR analysis

RANKL and RANK mRNA expressions were determined by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). MDA-MB-231, PC-3, MM.1S, and U266 cells were treated with butein for 24 hours. Total RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol (Invitrogen). One microgram of total RNA was converted to cDNA by SuperScript reverse transcriptase and then amplified by Platinum Taq polymerase using the SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen). The primers include those for RANKL (forward, 5′-CGTTGGATCACAGCACATCAG-3′; reverse, 5′-AGTATGTTGCATCCTGATCCG-3′), RANK (forward, 5′-GGGAAAGCACTCACAGCTAATTTG-3′; reverse, 5′-CAGCTTTCTGAACCCACTGTG-3′) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; forward, 5′-GTCTTCACCACCATGGAG-3′; reverse, 5′-CCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGC-3′). Cycling conditions were 30-s denaturation at 94°C, 30-s annealing at 56°C, and 30-s elongation at 72°C for 40 cycles. PCR products underwent electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels, and gel images were visualized under ultraviolet light and photographed.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays for NF-κB

To assess NF-κB activation, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) essentially as described previously 20.

Western blot analysis

To determine the levels of protein expression in the cytoplasm or nucleus, we prepared extracts 20 and fractionated them by 10% SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the proteins were electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blotted with each antibody, and detected by enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (GE Healthcare).

IKK assay

To determine the effect of butein on RANKL-induced IKK activation, we performed the IKK assay as described previously 20.

Interaction of butein with RANKL signaling proteins

To detect whether butein can modulate RANKL-induced association between RANK and TRAF6, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Briefly, RAW264.7 cells were seeded in 6 cm dish and treated with 25 μmol/L butein or media for 4 hours. Thereafter cells were exposed to RANKL (10 nmol/L) for 20 minutes, and prepared the whole cell extracts. RANK or TRAF6 antibody were added into the whole cell lysate and incubated at 4°C overnight with rotation. Protein A/G-agarose beads were then added and incubated with rotation for 3 hours at 4°C. After centrifugation, proteins were subjected to Western blot.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was done as previously described with some modifications 22. RAW264.7 cells (1 × 107) were incubated with indicated concentration of butein for 4 hours before treating with RANKL for 20 hour. PCR analyses were carried out for 39 cycles with primers 5′-CTTTCCTTCCCCAAGGAGTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCCCACACTGTAGGTTCTATCC-3′ (backward) for MMP-9 (NC_000068).

Flow cytometry analysis

To determine the effect of butein on RANKL-RANK interaction, RAW264.7 cells were treated with butein for 4 hour before stimulating with RANKL for 10 min. Thereafter cells were harvested and suspended in Dulbecco’s PBS containing 1% FBS and 0.1% sodium azide. The cells were then preincubated with 10% goat serum for 20 min and washed, and antibody against RANKL was added. After a 1 hour incubation at 4°C, the cells were washed and incubated for an additional 1 hour in FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG Abs and then analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and CellQuest acquisition and analysis software (BD Biosciences).

Results

The goal of the present study was to examine the effect of butein on RANK/RANKL signaling that leads to osteoclastogenesis. Whether butein could inhibit osteoclastogenesis induced by breast and prostate cancer cells and multiple myeloma was another focus of these studies. To examine these, we used the murine macrophage, RAW264.7 cell, as it is a well-established in vitro model for osteoclastogenesis 23.

Butein suppresses tumor cell-induced osteoclastogenesis

Osteoclastogenesis is commonly linked with certain type of cancers like breast cancer 24, prostate cancer 25 and multiple myeloma 26. Whether butein blocks tumor cell-induced osteoclastogenesis of RAW264.7 cells was investigated. As shown in Figure 1B, We found that incubating RAW264.7 cells with multiple myeloma MM.1S and U266 cells, breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells, and prostate cancer PC-3 cells induced osteoclast differentiation in each and that butein suppressed this differentiation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). Under these conditions, butein had no effect on cell viability as determined by the MTT assay (Supplementary Fig. 1). These results indicate that osteoclastogenesis induced by tumor cells is significantly suppressed by the presence of butein.

Butein modulates mRNA expression of RANKL in tumor cells

We then investigated how butein suppresses tumor cell-induced osteoclastogenesis. We used RT-PCR to examine whether human breast cancer, prostate cancer, and multiple myeloma cells express RANK and RANKL and whether the latter ligand is modulated by butein. We found that human multiple myeloma cells (MM.1S and U266), human breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231), and prostate cancer cells (PC-3) express both RANK. In comparison, RANKL was expressed by multiple myeloma and prostate cancer cells but not breast cancer cells (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Butein suppresses RANKL expression in multiple myeloma cells. (A) Total RNA was isolated and examined for expression of RANK and RANKL using RT-PCR. (B) Cells (0.5 × 106) were incubated with the indicated concentrations of butein for 24 hours. Total RNA was isolated and examined for expression of RANKL using RT-PCR. GAPDH was used as an internal control to show equal RNA loading.

Next we investigated whether butein can modulate the expression of RANKL in human cancer cells. As shown in Figure 2B, butein downregulated the mRNA expression of RANKL in a dose-dependent manner.

Butein suppresses RANKL-induced NF-κ B activation

To investigate whether butein suppresses RANKL-induced NF-κB activation in RAW264.7 cells, cells were either pretreated with the indicated concentration of butein for 24 hours or were left untreated and then exposed to RANKL. Nuclear extracts were prepared, and NF-κB activation was assayed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. The results indicated that RANKL activated NF-κB; however, butein suppressed NF-κB in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). Butein almost completely suppressed NF-κB activation at 2.5 μM of butein after 24 hours of treatment. Under these conditions, butein had no effect on cell viability as determined by the MTT assay.

Fig. 3.

RANKL induces NF-κB activation and butein suppresses it in a dose-dependent manner. (A) RAW264.7 cells (1 × 106) were incubated with the indicated concentrations of butein for 24 hours, treated with RANKL (10 nmol/L), and tested for NF-κB activation by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. Fold value is based on the value for medium (control), arbitrarily set at 1. The cell viability (C.V.) was determined by the MTT assay. (B) RAW264.7 cells (1 × 106) were incubated with the indicated concentrations of butein for 4 hours, treated with 10 nmol/L RANKL for 30 min, and assayed for NF-κB activation by electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

Next, to determine the optimum concentration of butein required to suppress the RANKL-induced NF-κB activation signaling pathway, we pretreated cells with a high concentration of butein for 4 hours and then exposed the cells to RANKL. After 4 hours of treatment, butein at 25 μM almost completely suppressed NF-κB activation (Fig. 3B).

Butein inhibits RANKL-induced IκBα phosphorylation and degradation

To determine whether inhibition of RANKL-induced NF-κB activation was due to inhibition of IκBα degradation, we pretreated cells with butein and then exposed them to RANKL for the indicated time periods. We then examined the cells for NF-κB in the nucleus by EMSA and for IκBα degradation in the cytoplasm by Western blot analysis. RANKL activated NF-κB in the control cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). RANKL induced peak NF-κB activation in RAW264.7 cells at 30 minutes, but RANKL failed to activate NF-κB in butein-pretreated cells. Moreover, RANKL induced IκBα degradation within 10 minutes and returned to normal level within 60 minutes (Fig. 4B). In contrast, cells pretreated with butein suppressed RANKL-induced degradation of IκBα (Fig. 4B)

Fig. 4.

Butein suppresses RANKL-induced IκBα degradation. (A) RAW264.7 cells (1 × 106) were incubated with or without butein (25 μmol/L) for 4 hours, treated with RANKL (10 nmol/L), and tested for NF-κB activation by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. (B) RAW264.7 cells (1 × 106) were incubated with butein (25 μmol/L) for 4 hours and then treated with RANKL (10 nmol/L) for the indicated times. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared, fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Western blot analysis was performed with anti-IκBα. (C) RAW264.7 cells (1 × 106) were pretreated with butein (25 μmol/L) for 4 hours, incubated with N-acetyl-leu-leu-norleucinal (ALLN) (50 μg/mL for 30 min), and then treated with RANKL (10 nmol/L) for 15 min. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared, fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Western blot analysis was performed using either anti-phospho-IκBα (top) or anti-IκBα (bottom). (D) RAW264.7 cells (3 ×106) were pretreated with butein (25 μmol/L) for 4 hours, incubated with 50 μg/mL ALLN for 30 min, and then incubated with RANKL (10 nmol/L) for the indicated times. Whole-cell extracts were immunoprecipitated using anti-IKKα antibody and analyzed by an immune complex kinase assay using recombinant GST-IκBα as described in Materials and Methods. To examine the effect of butein on the level of IKK proteins, whole-cell extracts were fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE and examined by Western blot analysis using anti-IKKα (middle) and anti-IKKβ (bottom) antibodies. (E) RAW264.7 cells were seeded in 6-cm plate and treated with or without butein (25 μmol/L) for 4 hours, and then incubated with RANKL (10 nmol/L) for 20 min. The cells were lysed and subjected to co-imunoprecipitation assays as mentioned in Materials and Methods. (F) RAW264.7 cells/were treated with butein for 4 hour, stimulated with RANKL and cells were harvested and suspended in Dulbecco’s PBS containing 1% FBS and 0.1% sodium azide. The RANKL-RANK interaction on cell surface was analyzed by flow cytometry analysis as described in Materials and Methods.

Next, we investigated the effect of butein on the phosphorylation of IκBα, which occurs before its ubiquitination and degradation of IκBα 27. We used the proteasome inhibitor N-acetyl-leu-leu-norleucinal (ALLN) to prevent RANKL-induced IκBα degradation. As shown in Figure 3C, RANKL induced IκBα phosphorylation in RAW264.7 cells, and butein inhibited this effect. Butein alone had no effect on phosphorylation of IκBα.

Butein inhibits RANKL-induced IκBα kinase activation

Because butein suppressed RANKL-induced phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα, we next examined whether butein can modulate the activity or the levels of IKK, which leads to IκBα phosphorylation. Immunocomplex kinase assay using cells treated with RANKL showed a clear increase in IKK activity (as indicated by the phosphorylation of GST-IκBα) within 2 minutes. In contrast, cells pretreated with butein did not phosphorylate GST-IκBα upon RANKL treatment (Fig. 4C, top panel). Neither RANKL nor butein affected the expression of IKKα or IKKβ proteins (Fig. 4C, middle and bottom panels).

Butein inhibits RANKL-induced RANK-TRAF6 association

Since RANKL is known to induce the association of TRAF6 with RANK and is involved in NF-κB activation, we analyzed the effect of butein in the association of RANK with TRAF6 by co-immunoprecipitation assay. For this, cell lysates from butein and RANKL treated and untreated were immunoprecipitated with anti-RANK and then blotted with anti-TRAF6. The results in Fig. 4E, demonstrate that RANKL enhanced the interaction between RANK and TRAF6, but butein markedly inhibited this interaction. These results suggest that butein affects RANKL-induced signaling.

Butein interferes binding of RANKL to RANK

Whether butein interfere with the interaction of RANKL with RANK, was also examined by FACS analysis. For this, cells were pre-incubated with butein for 4 hour before exposing to RANKL for 20 min, and then performed flow cytometric analysis by using RANKL antibody. Results demonstrated the binding of RANKL to RANK at the cell surface (Fig. 4F, right panel, dashed line) and treatment of cells with butein decreased the interaction of RANKL with RANK (Fig. 4F, right panel, solid line).

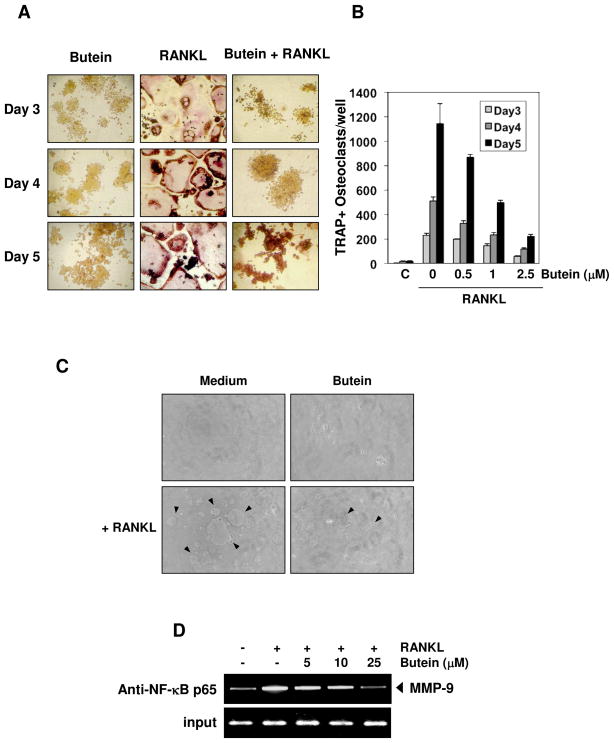

Butein blocks RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis

To determine the effect of butein on RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis, we pretreated RAW264.7 cells with different concentrations of butein in the presence of RANKL and allowed the cells to differentiate into osteoclasts. We found that RANKL induced osteoclastogenesis in the absence of butein at day 3 (Fig. 5A). In contrast, butein significantly decreased the differentiation into osteoclasts. Therefore, the formation of osteoclasts decreased with increasing concentrations of butein (Fig. 5B). As little as 0.5 μmol/L butein resulted in a significant effect on RANKL-induced osteoclast formation.

Fig. 5.

Butein represses RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. (A) RAW264.7 cells (5 × 103) were incubated with either medium or RANKL (5 nmol/L) or RANKL and butein (2.5 μmol/L) for 3, 4, or 5 days and then stained for TRAP expression. TRAP-positive cells were photographed. Original magnification, ×100. (B) RAW264.7 cells (5 × 103) were incubated with either medium or RANKL (5 nmol/L) along with the indicated concentrations of butein for 3, 4, or 5 days and then stained for TRAP expression. Multinucleated osteoclasts were counted. C = control cells exposed to medium alone. (C) RAW264.7 cells (3 × 103) were seeded into calcium phosphate apatite-coated plates, treated with butein (2.5 μmol/L) for 4 hour, and then with RANKL (5 nmol/L). After 5 day incubation, cells were lysed, and images obtained under light microscopy. Arrows, pit formation. (D) RAW264.7 cells pretreated with indicated concentration of butein for 4 hour, exposed to RANKL (10 nmol/L) for 20 hour, and the proteins were cross-linked with DNA with formaldehyde and then subjected to ChIP assay with an anti-p65 antibody.

Butein inhibits RANKL-induced bone resorption

Whether inhibition of RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis by butein leads to inhibition of bone resorption was investigated. To determine this, RAW264.7 cells were seeded into calcium phosphate apatite-coated plates, treated with butein along with RANKL, and then the resorption pit formation was analyzed after 5 days. Result showed that RANKL induced pit formation (Fig. 5C, arrows) and this was significantly suppressed by butein (Fig. 5C). Thus these results suggest that butein suppressed not only osteoclastogenesis, but also bone resorption.

Butein suppresses osteoclastogenesis through inhibition of NF-κ B binding to the MMP-9 promoter

Osteoclast differentiation is regulated by several genes, such as MMP-9, TRAP, c-Src, c-fos and cathepsin K 28. Whether butein regulates osteoclastogenesis through inhibition of NF-κB-regulated gene expression, was examined by chromatin immunoprecipitation assay, targeting NF-κB binding in the MMP-9 promoter. We found that butein suppressed the NF-κB binding to MMP-9 promoter (Fig. 5D). Overall, these results provide a direct evidence that butien inhibits osteoclastogenesis by suppressing NF-κB signaling pathway.

Butein acts at an early step in RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis

It normally takes up to 5 days for RAW264.7 cells to differentiate into osteoclasts in response to RANKL. To determine at which stage butein can inhibit osteoclastogenesis, we added butein to osteoclast differentiation cultures on different days after the addition of RANKL and checked its effect on osteoclast formation.

Butein potently inhibited osteoclastogenesis even when cells were exposed 24 hours after RANKL treatment (Fig. 6A and B). However, exposure of cells to butein at later stages was not effective in the blockade of osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 6A and B). These results suggest that butein can suppress differentiation of osteoclast precursors to osteoclasts but cannot reverse the differentiation process.

Fig. 6.

Butein inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis 24 hours after stimulation. RAW264.7 cells (5 × 103) were incubated with RANKL (5 nmol/L) and butein (2.5 μmol/L) for the indicated times. (A) Cells were cultured for 5 days after RANKL treatment and stained for TRAP expression. (B) Multinucleated osteoclasts (i.e., those containing three nuclei) were counted. C = control cells exposed to medium alone.

Discussion

Bone is a preferential site for metastasis of different type of cancers. Bone metastasis induces an increased morbidity, such as pain, nerve compression and fractures, and compromises the long-term survival. The chalcone, butein, is compound that is derived from numerous plants and has been shown to suppress inflammatory pathways and to induce tumor cell apoptosis. In this study, we investigated the effect of butein on RANKL-induced NF-κB activation and on the osteoclastogenesis induced by both RANKL and tumor cells. Our results indicated that RANKL activated NF-κB in osteoclast precursor cells through the activation of IKK and subsequent IκBα phosphorylation and degradation. The RANKL-induced NF-κB signaling pathway differs from that of the TNF-induced pathway. For instance, NF-κB–inducing kinase (NIK), which may function as an activator of IKKα, is necessary for RANKL-induced NF-κB activation 19 but is dispensable for TNF-induced NF-κB activation 29. Novack and colleagues 30 reported that NIK-deficient osteoclast precursors did not respond to RANKL in an in vitro differentiation system devoid of osteoblasts. We also found that butein inhibited RANKL-induced IKK activation, leading to the suppression of NF-κB activation.

The NF-κB pathway is known to play a critical role in both cancer cell growth and osteoclast formation 31. Ligand-induced activation of a number of cytokines and growth factor receptors, such as TNF receptor, tumor growth factor-β (TGF-β) receptor, and RANK, results in recruitment of receptor-associated kinases, including TGF-β-activated kinase-1 (TAK1), to the intracellular domain of the receptor 32. Recent studies, however, indicate that TAK1 plays a major role in the canonical pathway activated by cytokines through its interaction with TAK-binding proteins through phosphorylation of IKKα and β 33. Recently, there has been interest in the role of IKK in the progress of tumorigenesis, tumor cell metastasis, and osteoclastic bone resorption 34. In transgenic animal models of IKKα or IKKβ showed suppression of osteoclastogenesis and blockage of inflammation-induced bone loss 28, 35. Furthermore, activation of IKK is also known to accelerate the proliferation and metastasis of cancer cells, and the inhibitors of IKK have been shown to suppress these events in a number of disease models 36–39. Taken together, these data suggest that inhibition of IKK might have potential in the treatment of cancers that metastasize to bone.

We found that butein inhibited RANKL-induced NF-κB activation through suppression of IKK. In support of this, our group previously reported that butein inactivated TNF-induced NF-κB activation through suppression of TAK1 and inactivation of IKK by direct binding to cysteine residue 179 of IKKβ 17. Recently, small molecular inhibitors for IKK, celastrol, and parthenolide, are observed that they inhibited IKK activation by preventing the phosphorylation of TAK1, a let upstream of IKK, inhibited proliferation and migration of cancer cells in W256 cells 40. Indeed, parthenolide and celastrol suppressed trabecular bone loss and reduced the number and size of osteolytic bone lesion in rats 40. These findings support our results that butein abolishes RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis through suppression of IKK.

We found that butein also suppressed osteoclastogenesis induced by different tumor cells, and this was mediated through inhibition of RANK signaling. In case of cancer-induced osteoclastogenesis, an imbalance of the RANK/RANKL/OPG pathway is considered an important mechanism. Breast and prostate cancer and multiple myeloma cells are known to express RANKL 25, 26, 41, 42 and to exhibit constitutive NF-κB activation 36, 43, 44, thus implicating them in the induction of osteoclastogenesis via the expression of RANKL. In addition to this, these cancer cells express RANK, the receptor for RANKL, and RANKL stimulation can induce the migration of cancer cells 42, 45, 46. Pearse and colleagues 42 reported that multiple myeloma cells could stimulates osteoclastogenesis by upregulating the expression of RANKL and downregulating the expression of OPG at both the mRNA and protein levels in pre-osteoblastic or stromal cell co-culture.

We found that multiple myeloma cells (MM.1S and U266) and human prostate cancer cells (PC-3) showed the mRNA expression of RANKL, whereas the breast cancer cells we used (MDA-MB-231) did not. Treatment with butein reduced mRNA expression of RANKL in multiple myeloma and prostate cancer cells. Direct expression or production of RANKL by human multiple myeloma cells is controversial 47, 48. Despite this controversy, the existing data revealed that the RANKL/OPG balance is mainly involved in the osteoclastogenesis by myeloma cells through the bone marrow microenvironment despite myeloma cells produce RANKL or not.

Our results indicated that butein suppressed osteoclastogenesis induced by breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 cells while this cell line did not produce RANKL. Besides RANKL, the differentiation of osteoclast precursors into osteoclast is known to be regulated by other cytokines, such as macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IL-7 and TNFα. Recently, Rasheed et al 49 reported that butein downregulated the expression of various cytokines including TNFα by inhibiting NF-κB signaling pathway. Thus it is possible that butein suppresses MDA-MB-231-induced osteoclastogenesis through suppression of TNFα production.

To date, bisphosphonates represent the cornerstone of the management of bone metastasis or cancer-related bone disease 50, 51. However, not all patients respond to bisphosphonates, and such toxicities as renal impairment or osteonecrosis of the jaw can preclude the use of bisphosphonates 52. The development of novel therapies that reduce bone damage is important for optimizing the management of patients with solid tumors and multiple myeloma.

Recently denosumab (Prolia, Amgen), a humanized monoclonal neutralizing antibody to RANKL, was approved for the treatment and prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis and bone loss in patients with hormone-treated prostate or breast cancer 53. This RANKL antibody, however, has black box warnings for serious side effects such as severe jawbone problems (osteonecrosis), skin problems (dermatitis, rash, eczema, and serious skin infections), and hypocalcemia. The FDA has asked for new studies to show that there was no incidence of increased cancer. In addition, the price of $825 per injection at twice per year rate or $1650 per year is not affordable by most. For treatment of bone loss in cancer patients, the annual cost per patient could be approximately $20,000. Thus this antibody, although effective, is expensive and may have severe side effects.

Overall, our studies demonstrate that butein derived from traditional medicine is highly affordable, is safe, and can suppress osteoclast formation induced by different cancers through suppression of the same mechanism as Prolia. Future studies are needed to determine whether butein has the potential to suppress osteoclastogenesis in laboratory animals and in humans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Worley for carefully editing the manuscript. We will also like to thank Dr. Bryant Darnay for supplying us RANKL protein. Dr. Aggarwal is the Ransom Horne, Jr., Professor of Cancer Research. This work was supported by a grant from the Clayton Foundation for Research (B.B.A.), a core grant from the National Institutes of Health (CA-16 672), a program project grant from National Institutes of Health (NIH CA-124787-01A2), and grant from Center for Targeted Therapy of M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Coleman RE. Metastatic bone disease: clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27:165–76. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2000.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6243s–9s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kong YY, Yoshida H, Sarosi I, Tan HL, Timms E, Capparelli C, Morony S, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Van G, Itie A, Khoo W, Wakeham A, et al. OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature. 1999;397:315–23. doi: 10.1038/16852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suda T, Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Jimi E, Gillespie MT, Martin TJ. Modulation of osteoclast differentiation and function by the new members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor and ligand families. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:345–57. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Suda T. A new member of tumor necrosis factor ligand family, ODF/OPGL/TRANCE/RANKL, regulates osteoclast differentiation and function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;256:449–55. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka S, Miyazaki T, Fukuda A, Akiyama T, Kadono Y, Wakeyama H, Kono S, Hoshikawa S, Nakamura M, Ohshima Y, Hikita A, Nakamura I, et al. Molecular mechanism of the life and death of the osteoclast. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1068:180–6. doi: 10.1196/annals.1346.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Kelley M, Chang MS, Luthy R, Nguyen HQ, Wooden S, Bennett L, Boone T, Shimamoto G, DeRose M, et al. Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997;89:309–19. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dougall WC, Chaisson M. The RANK/RANKL/OPG triad in cancer-induced bone diseases. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:541–9. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandey MK, Sung B, Ahn KS, Aggarwal BB. Butein suppresses constitutive and inducible signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 activation and STAT3-regulated gene products through the induction of a protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:525–33. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.052548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Chan FL, Chen S, Leung LK. The plant polyphenol butein inhibits testosterone-induced proliferation in breast cancer cells expressing aromatase. Life Sci. 2005;77:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yit CC, Das NP. Cytotoxic effect of butein on human colon adenocarcinoma cell proliferation. Cancer Lett. 1994;82:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jang HS, Kook SH, Son YO, Kim JG, Jeon YM, Jang YS, Choi KC, Kim J, Han SK, Lee KY, Park BK, Cho NP, et al. Flavonoids purified from Rhus verniciflua Stokes actively inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis in human osteosarcoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1726:309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JC, Lee KY, Kim J, Na CS, Jung NC, Chung GH, Jang YS. Extract from Rhus verniciflua Stokes is capable of inhibiting the growth of human lymphoma cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004;42:1383–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim NY, Pae HO, Oh GS, Kang TH, Kim YC, Rhew HY, Chung HT. Butein, a plant polyphenol, induces apoptosis concomitant with increased caspase-3 activity, decreased Bcl-2 expression and increased Bax expression in HL-60 cells. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;88:261–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2001.d01-114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwashita K, Kobori M, Yamaki K, Tsushida T. Flavonoids inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis in B16 melanoma 4A5 cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2000;64:1813–20. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SH, Seo GS, Kim HS, Woo SW, Ko G, Sohn DH. 2′,4′,6′-Tris(methoxymethoxy) chalcone attenuates hepatic stellate cell proliferation by a heme oxygenase-dependent pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1322–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandey MK, Sandur SK, Sung B, Sethi G, Kunnumakkara AB, Aggarwal BB. Butein, a tetrahydroxychalcone, inhibits nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB and NF-kappaB-regulated gene expression through direct inhibition of IkappaBalpha kinase beta on cysteine 179 residue. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17340–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700890200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu H, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Solovyev I, Colombero A, Timms E, Tan HL, Elliott G, Kelley MJ, Sarosi I, Wang L, Xia XZ, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor family member RANK mediates osteoclast differentiation and activation induced by osteoprotegerin ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3540–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei S, Teitelbaum SL, Wang MW, Ross FP. Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa b ligand activates nuclear factor-kappa b in osteoclast precursors. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1290–5. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.3.8031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sung B, Pandey MK, Aggarwal BB. Fisetin, an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase 6, down-regulates nuclear factor-kappaB-regulated cell proliferation, antiapoptotic and metastatic gene products through the suppression of TAK-1 and receptor-interacting protein-regulated IkappaBalpha kinase activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:1703–14. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.034512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bharti AC, Takada Y, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) inhibits receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand-induced NF-kappa B activation in osteoclast precursors and suppresses osteoclastogenesis. J Immunol. 2004;172:5940–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.5940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters AH, Kubicek S, Mechtler K, O’Sullivan RJ, Derijck AA, Perez-Burgos L, Kohlmaier A, Opravil S, Tachibana M, Shinkai Y, Martens JH, Jenuwein T. Partitioning and plasticity of repressive histone methylation states in mammalian chromatin. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1577–89. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00477-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi Y, Mizoguchi T, Take I, Kurihara S, Udagawa N, Takahashi N. Prostaglandin E2 enhances osteoclastic differentiation of precursor cells through protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of TAK1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11395–403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chikatsu N, Takeuchi Y, Tamura Y, Fukumoto S, Yano K, Tsuda E, Ogata E, Fujita T. Interactions between cancer and bone marrow cells induce osteoclast differentiation factor expression and osteoclast-like cell formation in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;267:632–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Dai J, Qi Y, Lin DL, Smith P, Strayhorn C, Mizokami A, Fu Z, Westman J, Keller ET. Osteoprotegerin inhibits prostate cancer-induced osteoclastogenesis and prevents prostate tumor growth in the bone. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1235–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI11685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai FP, Cole-Sinclair M, Cheng WJ, Quinn JM, Gillespie MT, Sentry JW, Schneider HG. Myeloma cells can directly contribute to the pool of RANKL in bone bypassing the classic stromal and osteoblast pathway of osteoclast stimulation. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:192–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109 (Suppl):S81–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaisson ML, Branstetter DG, Derry JM, Armstrong AP, Tometsko ME, Takeda K, Akira S, Dougall WC. Osteoclast differentiation is impaired in the absence of inhibitor of kappa B kinase alpha. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54841–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uhlik M, Good L, Xiao G, Harhaj EW, Zandi E, Karin M, Sun SC. NF-kappaB-inducing kinase and IkappaB kinase participate in human T-cell leukemia virus I Tax-mediated NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21132–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novack DV, Yin L, Hagen-Stapleton A, Schreiber RD, Goeddel DV, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. The IkappaB function of NF-kappaB2 p100 controls stimulated osteoclastogenesis. J Exp Med. 2003;198:771–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clement JF, Meloche S, Servant MJ. The IKK-related kinases: from innate immunity to oncogenesis. Cell Res. 2008;18:889–99. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karin M. The beginning of the end: IkappaB kinase (IKK) and NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27339–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prickett TD, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Broglie P, Muratore-Schroeder TL, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Brautigan DL. TAB4 stimulates TAK1-TAB1 phosphorylation and binds polyubiquitin to direct signaling to NF-kappaB. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19245–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800943200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Sarosi I, Yan XQ, Morony S, Capparelli C, Tan HL, McCabe S, Elliott R, Scully S, Van G, Kaufman S, Juan SC, et al. RANK is the intrinsic hematopoietic cell surface receptor that controls osteoclastogenesis and regulation of bone mass and calcium metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1566–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruocco MG, Maeda S, Park JM, Lawrence T, Hsu LC, Cao Y, Schett G, Wagner EF, Karin M. I{kappa}B kinase (IKK){beta}, but not IKK{alpha}, is a critical mediator of osteoclast survival and is required for inflammation-induced bone loss. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1677–87. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park BK, Zhang H, Zeng Q, Dai J, Keller ET, Giordano T, Gu K, Shah V, Pei L, Zarbo RJ, McCauley L, Shi S, et al. NF-kappaB in breast cancer cells promotes osteolytic bone metastasis by inducing osteoclastogenesis via GM-CSF. Nat Med. 2007;13:62–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guzman ML, Rossi RM, Neelakantan S, Li X, Corbett CA, Hassane DC, Becker MW, Bennett JM, Sullivan E, Lachowicz JL, Vaughan A, Sweeney CJ, et al. An orally bioavailable parthenolide analog selectively eradicates acute myelogenous leukemia stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 2007;110:4427–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-090621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kishida Y, Yoshikawa H, Myoui A. Parthenolide, a natural inhibitor of Nuclear Factor-kappaB, inhibits lung colonization of murine osteosarcoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:59–67. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jourdan M, Moreaux J, Vos JD, Hose D, Mahtouk K, Abouladze M, Robert N, Baudard M, Reme T, Romanelli A, Goldschmidt H, Rossi JF, et al. Targeting NF-kappaB pathway with an IKK2 inhibitor induces inhibition of multiple myeloma cell growth. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:160–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Idris AI, Rojas J, Greig IR, Van’t Hof RJ, Ralston SH. Aminobisphosphonates cause osteoblast apoptosis and inhibit bone nodule formation in vitro. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;82:191–201. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9104-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schubert A, Schulz H, Emons G, Grundker C. Expression of osteoprotegerin and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand (RANKL) in HCC70 breast cancer cells and effects of treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone on RANKL expression. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24:331–8. doi: 10.1080/09513590802095845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearse RN, Sordillo EM, Yaccoby S, Wong BR, Liau DF, Colman N, Michaeli J, Epstein J, Choi Y. Multiple myeloma disrupts the TRANCE/osteoprotegerin cytokine axis to trigger bone destruction and promote tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11581–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201394498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bharti AC, Donato N, Singh S, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) down-regulates the constitutive activation of nuclear factor-kappa B and IkappaBalpha kinase in human multiple myeloma cells, leading to suppression of proliferation and induction of apoptosis. Blood. 2003;101:1053–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pajonk F, Pajonk K, McBride WH. Inhibition of NF-kappaB, clonogenicity, and radiosensitivity of human cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1956–60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.22.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones DH, Nakashima T, Sanchez OH, Kozieradzki I, Komarova SV, Sarosi I, Morony S, Rubin E, Sarao R, Hojilla CV, Komnenovic V, Kong YY, et al. Regulation of cancer cell migration and bone metastasis by RANKL. Nature. 2006;440:692–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armstrong AP, Miller RE, Jones JC, Zhang J, Keller ET, Dougall WC. RANKL acts directly on RANK-expressing prostate tumor cells and mediates migration and expression of tumor metastasis genes. Prostate. 2008;68:92–104. doi: 10.1002/pros.20678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farrugia AN, Atkins GJ, To LB, Pan B, Horvath N, Kostakis P, Findlay DM, Bardy P, Zannettino AC. Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand expression by human myeloma cells mediates osteoclast formation in vitro and correlates with bone destruction in vivo. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5438–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giuliani N, Bataille R, Mancini C, Lazzaretti M, Barille S. Myeloma cells induce imbalance in the osteoprotegerin/osteoprotegerin ligand system in the human bone marrow environment. Blood. 2001;98:3527–33. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rasheed Z, Akhtar N, Khan A, Khan KA, Haqqi TM. Butrin, isobutrin, and butein from medicinal plant Butea monosperma selectively inhibit nuclear factor-kappaB in activated human mast cells: suppression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-8. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 333:354–63. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.165209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lipton A. Bisphosphonate therapy in the oncology setting. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2003;8:469–88. doi: 10.1517/14728214.8.2.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Terpos E, Rahemtulla A. Bisphosphonate treatment for multiple myeloma. Drugs Today (Barc) 2004;40:29–40. doi: 10.1358/dot.2004.40.1.799436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kyle RA, Yee GC, Somerfield MR, Flynn PJ, Halabi S, Jagannath S, Orlowski RZ, Roodman DG, Twilde P, Anderson K. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 clinical practice guideline update on the role of bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2464–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Body JJ, Facon T, Coleman RE, Lipton A, Geurs F, Fan M, Holloway D, Peterson MC, Bekker PJ. A study of the biological receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand inhibitor, denosumab, in patients with multiple myeloma or bone metastases from breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1221–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.