Abstract

Background

Although it is now common to see spirituality as an integral part of health care, little is known about how to deal with this topic in daily practice.

Aim

To investigate the literature about GPs' views on their role in spiritual care, and about their perceived barriers and facilitating factors in assessing spiritual needs.

Design

Qualitative evidence synthesis.

Method

The primary data sources searched were MEDLINE, Web of Science, CINAHL, Embase, and ATLA Religion Database. Qualitative studies that described the views of GPs on their role in providing spiritual care, or that described the barriers and facilitating factors they experience in doing so, were included. Quantitative studies, descriptive papers, editorials, and opinion papers were excluded.

Results

Most GPs see it as their role to identify and assess patients' spiritual needs, despite perceived barriers such as lack of time and specific training. However, they struggle with spiritual language and experience feelings of discomfort and fear that patients will refuse to engage in the discussion. Communicating willingness to engage in spiritual care, using a non-judgemental approach, facilitates spiritual conversations.

Conclusion

The results of the studies included here were mostly congruent, affirming that many GPs see themselves as supporters of patients' spiritual wellbeing, but lack specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes to perform a spiritual assessment and to provide spiritual care. Spirituality may be of special consequence at the end of life, with an increased search for meaning. Actively addressing spiritual issues fits into the biopsychosocial-spiritual model of care. Further research is needed to clarify the role of the GP as a spiritual care giver.

Keywords: general practitioners, primary health care, spirituality

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization, in defining palliative care, combines control of pain and other symptoms with psychological, social, and spiritual care.1 Research into spirituality and health has developed into a thriving field over the last 20 years, as is evident from the more than 5000 citations that appear when the MeSH term ‘spirituality’ is entered in CINAHL or MEDLINE.2 It is now common to see attention to spirituality cited as an ethical obligation of professional care.3,4 The professional literature in medicine,5,6 nursing,7,8 psychology,9 and social work10 affirms this obligation.

To identify points of agreement about spirituality as it applies to health care, and to make recommendations to advance the delivery of qualified spiritual care in palliative care, a consensus conference was held on 17-18 February 2009, in Pasadena, California. The conference was based on the belief that spiritual care is a fundamental component of quality palliative care. The participants agreed upon the following definition:

‘Spirituality is the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.’11

There is little guidance, however, on how to deal with spirituality in daily practice. In the medical literature, there is considerable interest in and debate about how patients' religion and spirituality should be addressed. 12–17 Regardless of religious background, patients' willingness to discuss spiritual health issues may depend on the qualities of physicians, such as openness, a non-judgmental nature, respect for the spiritual views of others, and attitudes towards spiritual health. Patients' views of how physicians should address spiritual issues may favour a direct, principle-based, patient-centred approach in the context of ‘getting to know the patient’, rather than more structured approaches such as using spiritual-assessment tools.18

There are well-defined recommendations on providing spiritual care in hospitals or hospices, including collaboration among the members of multidisciplinary teams.11 In the outpatient setting, having a multidisciplinary team is more challenging. There are no generally accepted guidelines or practices for spiritual care in this arena. GPs often coordinate patient-centred care in outpatient settings. It is therefore reasonable to assume that it is the GP's role to organise and provide spiritual care for their patients as well. Perhaps in more complex situations, GPs should collaborate with a multidisciplinary team that contains professional spiritual-care providers.

The aim of this article is to provide a solid overview of GPs' views about their role in spiritual care, and the barriers and facilitating factors they experience in providing this care. Good qualitative research in this field has already been done, but there is no reviewarticle to organise and summarise these studies. In this qualitative evidence synthesis, the authors searched for an answer to the following questions: (a) What are the barriers and the facilitating factors that GPs experience in assessing the need for spiritual care and in providing spiritual care? (b) What are the views of GPs about their role in spiritual care?

How this fits in

Research into spirituality and health has developed into a thriving field over the last 20 years. There is little guidance, however, on how to deal with spirituality in general practice. This qualitative evidence synthesis is the first to collect and summarise the existing qualitative research about GPs' views on their role as spiritual care givers, and their perceived barriers and facilitating factors in assessing spiritual needs.

METHOD

Design

A qualitative evidence synthesis was conducted using thematic analysis. The strength of thematic analysis lies in its potential to draw conclusions based on common elements across otherwise heterogeneous studies.19 Conclusions from thematic analysis fulfil an important research aim of qualitative research in generating hypotheses, an area to which traditional systematic reviews are poorly suited.20

Databases

The search was performed in five databases (MEDLINE, Web of Science, CINAHL, Embase, and ATLA Religion Database), with various combinations of search terms, and without date restrictions, in order to make the search strategy as sensitive as possible (Table 1). The authors decided not to include psychological or sociological databases, because they were convinced that these domains would not contribute to the answer to the research questions. After selection of the relevant full-text articles, a cited reference search was made (in the database Web of Knowledge) from each article, in order to complete the list of relevant articles. For the search strategy, see Box 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included qualitative studies

| Study and characteristics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanyi et al, 200929 How family practice physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants incorporate spiritual care in practice | Kelly et al, 200830 GPs' experiences of the psychological aspects in the care of a dying patient | Olson et al, 200631 Mind, body, and spirit: family physicians' beliefs, attitudes, and practices regarding the integration of patient spirituality into medical care | Ellis and Campbell, 200527 Concordant spiritual orientations as a factor in physician–patient spiritual discussions: a qualitative study | Murray et al, 200328 GPs and their possible role in providing spiritual care: a qualitative study28 | Ellis et al, 200226 What do family physicians think about spirituality in clinical practice? | Grant et al, 200432 Spiritual issues and needs: perspectives from patients with advanced cancer and nonmalignant disease. A qualitative study | |

| Country | US | Australia | US | US | Scotland | US | Scotland |

| Study participants | 3 male GPs, 5 female nurse practitioners, and 2 male physician assistants | 15 GPs (8 males and 7 females) | 17 GP residents (11 males and 6 females) | 10 GPs (7 males and 3 females) and 10 patients of these GPs | 40 GPs (no information about male/female distribution) | 13 GPs (10 males and 3 females) | 20 GPs (no information information about male/female distribution) |

| Setting | GPs employed in three large clinics in the Minneapolis/St Paul area | GPs who referred their patient to a hospice/home care specialist palliative care service | Third-year GP residents completing residency training in a South west US medical school | Board-certified Missouri GPs caring for a patient with chronic or terminal illness | GPs of 20 patients with inoperable lung cancer and 20 patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) grade III or IV cardiac failure | Board-certified Missouri GPs from different practice types (academic/community practice; urban/rural) | GPs of 20 patients with a range of advanced malignant and non-malignant illnesses (cancer, cardiac failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), motor neurone disease) |

| Data collection | Semi-structured interviews | Individual case-review discussions guided by key questions within a semi-structured format | In-depth interviews | Semi-structured interviews | Serial telephone interviews | Semi-structured interviews | In-depth interviews |

| Data analysis | Phenomenological methodology described by Colaizzi (1978)33 | Analysis to identify convergence of key topics that were presented and then categorised into common themes | Grounded theory | Constant comparative method | Thematic analysis | Iterative process tomake an initial template for coding data; code revisions until consensus was reached about salient issues or themes | Analysis ongoing throughout fieldwork; emergent themes fed back into data collection and coding strategy; review of the evolving themes |

Box 1.

Search strategy—July 2010

| Database | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE (PubMed) | “Spirituality”[Mesh] AND “Physicians, Family”[Mesh] |

| “Spirituality”[Mesh] AND “Primary Health Care”[Mesh] | |

| “Holistic Health”[Mesh] AND “Physicians, Family”[Mesh] | |

| “Holistic Health”[Mesh] AND “Primary Health Care”[Mesh] | |

| Web of Science (ISI Web of Knowledge) | “Spiritual*” AND “Family Physician*” |

| “Spiritual*” AND “General Practic*” | |

| “Spiritual*” AND “Primary Care” | |

| “Holistic” AND “Family Physician*” | |

| “Holistic” AND “General Practic*” | |

| “Holistic” AND “Primary Care | |

| CINAHL | “Spiritual*” AND “Family Physician*” |

| “Spiritual*” AND “General Practic*” | |

| “Spiritual*” AND “Primary Care” | |

| “Holistic” AND “Family Physician*” | |

| “Holistic” AND “General Practic*” | |

| “Holistic” AND “Primary Care | |

| Embase | “Spiritual care” AND “Primary Health Care” |

| “Spiritual care” AND “Primary Medical Care” | |

| “Spiritual care” AND “General Practitioner” | |

| ATLA Religion Database | “Spiritual*” AND “Family Physician*” |

| “Spiritual*” AND “Physician*” | |

| “Spiritual*” AND “Primary Care” | |

| “Holistic” AND “Family Physician*” | |

| “Holistic” AND “Physician*” | |

| “Holistic” AND “Primary Care” | |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In the articles that were found, a first selection was made by reading the title and abstract. This selection was made by two independent authors, who compared and discussed their results until agreement was reached. The selection of relevant publications was based on the following inclusion criteria: the article had to describe the views of GPs on their role in addressing or providing spiritual care, or the barriers and facilitating factors that GPs experience in addressing or providing spiritual care. Only those articles in which spirituality was understood in the same sense as the following definition were taken into account:

‘Spirituality is the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.’11

Publications with interpretations of spirituality other than the definition presented earlier were excluded, such as complementary and alternative medicine or spiritual healing. Articles about holistic health were also excluded if the spiritual component was not investigated separately from the physical, psychological, and social component. Studies that described views of multiple groups of professional care givers (for example, nurses, GPs, and chaplains) were included if the findings of the views of the GPs were described separately from the other professional groups. Only qualitative research published in English was included. No article was excluded on the basis of setting. Outpatient settings were included, as well as hospital or hospice settings. The authors did not exclude studies on the basis of origin or religion.

According to the guidance of the Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group, where critical appraisal is viewed as a technical and paradigmatic exercise, it is worth considering limiting the type of qualitative studies to be included in a systematic review. The authors suggests restricting included qualitative research reports to empirical studies with a description of the sampling strategy, data-collection procedures, and the type of data analysis used.

These empirical studies should include the methodology chosen and the methods or research techniques opted for, since this facilitates the systematic use of critical appraisal, as well as a more paradigmatic appraisal process. Therefore, descriptive papers, editorials, and opinion papers were excluded.21

Critical appraisal

Critical-appraisal instruments should be regarded as technical tools to assist in the appraisal of qualitative studies, looking for indications in the methods or discussion section that add to the level of methodological soundness of the study. This judgement determines the extent to which the reviewers may have confidence in the researcher's competence in being able to conduct research that follows established norms,22 and is a minimum requirement for critical assessment of qualitative studies.21 The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool was selected for this qualitative evidence synthesis because, according to a recent study from Hannes et al,23 it appears to be the most coherent instrument in evaluating the validity of qualitative research.

Analysis

Thematic analysis was used as a method for analysis and synthesis of the selected papers. Thematic analysis is a tried and tested method that preserves an explicit and transparent link between the conclusions and text of the primary studies; as such, it preserves principles that have traditionally been important to systematic reviewing.24 Thematic analysis has three stages: line-by-line coding of the text, development of ‘descriptive themes’, and generation of ‘analytical themes’. While the development of descriptive themes remains ‘close’ to the primary studies, the analytical themes represent a stage of interpretation whereby the reviewers ‘go beyond’ the primary studies and generate new interpretive constructs, explanations, or hypotheses.24 After careful inductive coding (both descriptive and interpretive), recurring themes were located. The qualitative software program ATLAS.ti 6.2 was used to code, sort, and assist in data analysis.

RESULTS

Results of the searches in the five databases

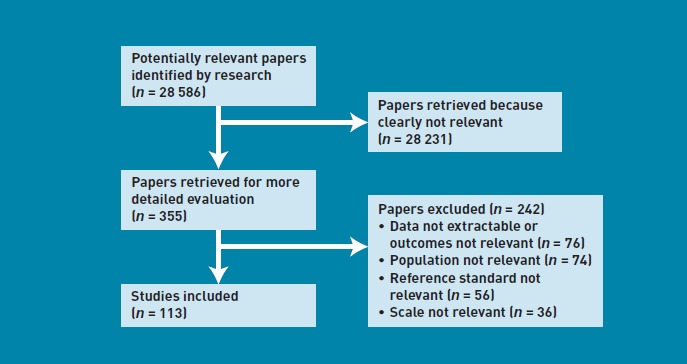

The flow diagram of the study-selection process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study-selection process.

In MEDLINE, 533 publications were retrieved. In Web of Science, the search yielded 333 articles. The search in CINAHL resulted in 264 articles, and in Embase, 24 articles were identified with the combination of search terms. Finally, in the ATLA Religion Database, another 66 articles were found.

Seventy-two possible relevant articles were selected after reading titles and abstracts. The full texts of those articles were read carefully, and a second selection was made, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria as described above. Twenty full-text articles with relevant content remained. A cited reference search (in Web of Knowledge) was done from these 20 articles, to see if other relevant publications could be added to the list. The 20 articles were cited 256 times. Of these cited articles, eight were already included. After reading the other 248 articles, two relevant publications were added, bringing the total count to 22 relevant full-text articles. One more relevant publication was recommended by an expert. Eleven of the 23 articles were excluded because they contained quantitative research (all self-administered surveys with closed-ended questions), and five more were excluded because they were opinion or descriptive papers. The other seven articles with qualitative research were used for further assimilation.

Critical appraisal

The JBI tool was used for critical appraisal of the seven selected papers.25 This tool consists of 10 criteria (Appendix 1). No additional exclusions were made after technical appraisal, in view of the high quality of the seven articles. Table 1 summarises the demographic and methodological characteristics of the included qualitative studies.26–32

Analysis

Table 2 shows a thematic matrix summarising the study results; role of the GP as spiritual carer, barriers perceived by GPs in assessing and providing spiritual care, and facilitating factors perceived by GPs in assessing and providing spiritual care.

Table 2.

Thematic matrix: role of the GP in spiritual care, and barriers and facilitating factors in spiritual care giving

| Role of the GP as a spiritual care giver | What? | How? | When? | Why? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Identifying and assessing spiritual needs | • Listening to the patient | • Most important during critical points of clinical care | • Spiritual care is an important aspect of patient care | |

| • Being a facilitator and encouragerof the patients' spiritual values | • Validating patients' spiritual beliefs | • Patients should take the initiative to start spiritual discussions | • Scientific evidence linking spirituality and positive health outcomes and values | |

| • Providing spiritual care appropriate to patients' beliefs | • Remaining with patients during times of need | • In answer to spiritual issues or questions, raised by the patient | ||

| • Not imposing own beliefs and values | • Being respectful of patients' beliefs | |||

| • Exhibiting a positive caring demeanourthat is genuine and non-judgemental | ||||

| • Approaching spiritual discussions with gentleness, reverence, sensitivity, and integrity | ||||

| • Being present with the patient | ||||

| • Both structured (such as, a spiritual-assessment tool) and unstructured forms of spiritual assessment | ||||

| Barriers | Physician factors | Patient factors | Contextual factors | |

| • Feeling uncertain initiating spiritual discussions | • Patient being the ‘wrong sort of person’ | • Lack of formal training and appropriate strategies | ||

| • Fearthat patients will misinterpret spiritual discussions as pushing religion | • Time as a limiting factor | |||

| • Concern about invasion of patients' privacy | • Setting (for example, the examination room) | |||

| • Fear of causing discomfort | • Lack of discussion of the role of spirituality among care providers | |||

| • Struggle with the spiritual language | • Lack of continuity of managed care | |||

| • Thinking that spiritual issues have lower priority than other medical concerns | ||||

| • Belief that spiritual discussions will not influence patients' lives | ||||

| • Lack of physician spiritual awareness | ||||

| • Different belief systems between physician and patient | ||||

| Facilitating factors | Physician factors | Patient factors | Contextual factors | |

| • Communicating a willingness to engage in (and have time for) spiritual discussions | • Patient being ‘the right sort of person’ | • Visiting patients at the bedside or at home | ||

| • Good communication techniques (such as friendly body language) | • Patients visiting the physician frequently | • Co-workers reinforcing the GP's role as a spiritual care giver | ||

| • Assuring patients that spiritual confidences will be received in a non-judgemental fashion | • High degree of physician–patient cultural concordance | |||

| • Patient-centred approach | ||||

| • Taking care not to abuse their position | ||||

| • A diplomatic approach when the spiritual beliefs of the physician and patient differ | ||||

| • Physicians being more spiritually inclined | ||||

Role of the GP as spiritual care giver

What is the perceived role of a GP in spiritual care?

Most of the GPs expressed the belief that it was their responsibility to identify and assess patients' spiritual needs:26–29

‘That's a silly question, isn't it? If I saw myself as dealing just with the physical problems I wouldn't get anywhere. I couldn't do the job. You would just push the button and get one answer. That's not what I do.’28

Despite the fact that most GPs were convinced that it is their task to identify their patients' spiritual resources and goals,26,27 a minority of physicians were opposed to addressing spiritual issues with patients, especially if they felt that this referred specifically to ‘religion’, because they felt that discussing religion was not part of their role as a doctor.30 However, the GPs who accepted the importance of conducting a spiritual assessment suggested that it often meant struggling with the unanswerable nature of spiritual concerns, questions, and dilemmas:31

‘A lot of times … You want a solution for A and B, A + B = D. But a lot of the times you never get that answer It's a journey and a process, not just a patient with a disease. This is a person who's married; they go to church or whatever beliefs they have. It's about trying to get to know a patient and understand how their life is “outside” of their disease, “outside” of our clinic.’31

GPs viewed themselves as facilitators and encouragers of patients' spiritual values, and as resources rather than as spiritual counsellors.26 They noted that encouraging patients to use spiritual practices that had helped them in the past to manage difficult circumstances was a method by which they provided spiritual care:29,32

‘If the patient says … “I don't go to church, I don't pray”; then I will encourage them to look at, and to think about what gives them strength and hope because we all have that spiritual aspect of ourselves …’29

In general, however, participants noted that they would only encourage what they personally judged to be positive spirituality:

‘If it's some ritual and I think there's something bizarre about it, then I am not going to encourage that… Don't stop your lisinopril and don't stop your Prozac.’29

After spiritual assessment has been carried out, most GPs perceived that they may also have a role in providing spiritual care, by offering therapies (answers, suggestions, or exercises) related to patients' questions and appropriate to patients' beliefs and values.26,28

Why should GPs provide spiritual care?

Physicians who regularly discussed spirituality believed that the scientific evidence linking spirituality and positive health outcomes justified their actions:26,29

‘Every physician ought to be dealing with [patients'] spiritual issues. [For example,] how can you justify not talking about spirituality to a patient with depression when you can prove scientifically that strengthening faith commitment helps them? It really comes down to a quality-of-care issue.’26

Besides the scientific evidence, the GPs who overtly discussed spiritual issues in spite of perceived barriers did so because of its relevance to their patients; they perceived spiritual care to be an important aspect of patient care:29,31,32

‘The advantages [of integrating spirituality in medicine] are to improve how people heal… [second], I think you develop a closer bond with the patient and better understanding of them and their family and what they go through with pain and ultimately that leads you to take better care of them.’31

When should GPs provide spiritual care?

Most GPs reported that they would leave it to their patients to raise the topic of spiritual beliefs:26,28,30,31

‘It's one of those areas where you need a small amount of the patient's permission to get started and a lot more of the patient's permission to finish.’26

In general, GPs accepted that if spiritual issues or questions were raised, they should be responded to.26,28–32 Spiritual issues can be discussed if the patient raises the topic but, generally, GPs address patients' spirituality during critical points of clinical care (for example, terminal diagnosis), with a few addressing it throughout the continuum of care:26,29,31,32

‘… certainly chronic conditions … when it gets to these potentially mortal, morbid sorts of situations in health care, you do see a lot more of “Why me? Why is this happening? What have I done?”.’29

How should GPs provide spiritual care?

GPs universally viewed themselves as sources of support for patients through listening, validating spiritual beliefs, and remaining with patients during times of need:26,29

‘I don't have to be a spiritual master. I can be a human being, trying to connect with another human being. That is a healing experience.’26

Several GPs expressed concern about being respectful of patients' beliefs without imposing their own beliefs and values:26,31

‘I can't even describe how negative it [would be] for me to impose my spiritual beliefs on [my] patients.26

GPs emphasised that they provided spiritual care to their patients by exhibiting a positive caring demeanour that was genuine and non-judgemental.29 They found it very important to approach spiritual discussions with gentleness, reverence, sensitivity, and integrity.26 Participants in one study expressed the view that the mere act of ‘being present’ with the patient for a few minutes can be a powerful spiritual intervention.29

’I think I try to do it by keeping high moral standards with my interactions with patients and ethical standards … I do this by trying to remain … nonjudgmental… and open to whatever it is their concerns are. I think I imply this with body language and good eye contact.’29

The physicians who regularly address spiritual issues use screening questions that they tend to ask in response to a patient's cues or crisis. They follow principles of spiritual assessment, but none reported the routine use of a currently available spiritual-assessment tool.26 Responders who reported conducting spiritual assessment described using both structured (that is, following a sequence of questions to prompt discussion) and unstructured (for example, following up on a comment or phrase from a patient that might indicate spiritual life) forms of spiritual assessment.31

Barriers perceived by GPs in assessing and providing spiritual care

Physician barriers

GPs often feel uncertain about initiating spiritual discussions. They have a fear of alienating or causing discomfort in their patients.26,29 The following comment reflects some of the dissonance that exists for many GPs. They generally feel that addressing spirituality is important, but are uncertain about how to do so appropriately:

‘The barrier would be myself, because I'm a little hesitant on approaching some issues [spirituality], especially for someone who's here for ankle twisting. But it's my own personal belief not to try to infringe on other people's personal beliefs and judge them, but just try and find out about them.’31

GPs not only feel discomfort about initiating spiritual discussions, but they also struggle with the language describing such existential and spiritual suffering.31 They feel reticence about approaching the subject directly, because of fears that patients will refuse to discuss it or consider their raising spiritual questions inappropriate.26,29 They also fear that patients will misinterpret discussion of spirituality as pushing religion.26,27,29

One GP strongly opposed the initiation of spiritual discussions, out of concern about role definition and invasion of patients' privacy. This physician felt that spiritual matters were ‘no more in the physician's domain than questions regarding patients' finances or their most evil thoughts’.26 In other studies, some GPs also felt that it would be inappropriate to raise such intimate issues.29,32

GPs reporting infrequent spiritual assessment expressed the view that spiritual issues have lower priority than other medical concerns.26 Almost all GPs noted that physicians and patients whose views about the importance of spirituality differ experience such barriers.27 Another barrier reported by GPs is the belief that spiritual discussions will not influence patients' illnesses or lives.26

An important barrier perceived by GPs is their own spirituality. Lack of spiritual awareness or inclination on the part of physicians may be a barrier to addressing spiritual issues. Many GPs identified the theme of physicians' own ‘spiritual place’ or ‘centre’ as among the most influential factors determining whether they addressed spirituality in clinical care:26,31

‘[The barrier] is physicians' own belief system. That either it's inappropriate for them to talk about it or it's not a “medical” problem so they shouldn't be addressing it. There are people who just don't think it's really what they should be doing. They should be talking about diabetes and hypertension and taking care of those things, and letting the priest or the family or whoever talk about these other things. Those physicians I find are usually people who are not very spiritually in-tune themselves. Therefore they don't think it's important to other people.’31

Almost all GPs commented that different belief systems may create barriers to spiritual discussions. They noted that physicians and patients whose views about the importance of spirituality differ, or who differ in their belief in a higher power or God, experience such barriers.26,27,31,32 Olson and colleagues observed that the few GPs who did not report that they assessed patients' spirituality in clinical care all similarly related that they themselves were not religious or spiritual:31

I'm not very religious. However, I think I'm a very spiritual person. One of the hardest questions I've had to answer, a patient asked me if I was a Christian. If I told her the truth, that I am not, would she still be as open and interactive ?I told her the truth and that if she felt like Christianity was an important part of her life I would understand.’31

However, in another study by Kelly and colleagues, in response to probes regarding exploration of spiritual issues, reference to the practitioner's own particular religious or spiritual beliefs did not emerge.30

Patient barriers

In response to the question ‘What factors constrain discussion of spiritual needs?’ a theme emerged about patients being the ‘wrong sort of person’.28 Some GPs described patients in significant spiritual need as ‘unreachable’, ‘vulnerable’, ‘difficult to get in touch with’ patients, who often displayed a strong facade of coping, covering a refusal to accept their mortality:32

‘I certainly do see these as part of my role and am keen to do more. But it's not possible with everyone. Some people are very open to it and others are like a brick wall. You can't make people talk to you about death and dying. The same with relatives too. Sometimes you can involve them and sometimes you can't.’28

Contextual barriers

A lot of GPs feel uncomfortable with discussions of spirituality with patients because of lack of formal training and appropriate strategies. They feel they lack the skill to ‘do spiritual care’.26,29,32

Time was mentioned almost unanimously as a limiting factor.26,28,29,31,32 Some of the GPs admitted though that time was not a major problem compared with the perceived importance of spiritual care to the providers' practice.29

But, yes, I mean, I think it is part of our job, you know, we try and … well most of us try and practise [a] fairly holistic type of approach (laughing) and it's difficult, it's frustrating when we can't spend time with people but you have to realise that, you know, you're a limited resource and, you know, if we spend three-quarters of an hour with one patient, you're spending 5minutes with the other three (laughing).’28

The setting can also be a barrier, for example, an examination room, where the patient does not feel at ease.26 Finally, some organisational factors were also identified as barriers, such as lack of discussion of the role of spirituality among care providers,29 and lack of continuity of managed care.26

Facilitating factors perceived by GPs in assessing and providing spiritual care

Physician factors

Responders noted that characteristics facilitating patients' discussions of sexuality and other sensitive issues also facilitate conversations about spirituality. These characteristics include communicating a willingness to engage in (and having the time for) such discussions, and assuring patients that spiritual confidences will be received in a non-judgemental fashion. One said that ‘bringing [spirituality] to the table’ along with other sensitive issues helps patients know ‘what you're interested in and gives them the option of deciding to pursue it or not’.26 All responders supported a patient-centred approach to spiritual assessment, in which physicians act with integrity and take care not to abuse their position.26,27

A diplomatic approach by the physician facilitates spiritual discussions when the spiritual beliefs of physician and patient differ.27 Some communication techniques serve as facilitating factors in addressing spiritual issues, such as paying active attention to patient cues or questions, asking clarifying questions to ensure accurate identification of spiritual issues, friendly body language, and good eye contact.26,29 Generalising words away from their religious context may also be a facilitating factor.27

Just as GPs' own spirituality can be a barrier to spiritual discussions, it can also be a very powerful facilitating factor Physicians who are more spiritually inclined are more likely to address spiritual issues with patients.26,31

‘When I have conversations about spiritual issues, it's usually been at my initiation … because I'm more concerned about religious sorts of things than many physicians.’26

Patient factors

Just as GPs said that there are ‘wrong sorts of patients’ to have spiritual discussions with, they also identify ‘right sorts of patients’, who facilitate the provision of spiritual care:28

She's a particularly nice lady, a very stoic, insightful, intelligent lady, and has quite a positive outlook on life, so she has made it remarkably easy for the health professionals who encounter her to help her28

When patients visit the practice frequently, this can also facilitate the provision of spiritual care.29

Most GPs viewed a high degree of physician-patient cultural concordance as an important facilitator of spiritual interactions. Cultural concordance may denote similarity in backgrounds, life experiences, and spiritual/religious orientation. Responders said that shared spiritual viewpoints allow spiritual interventions that would not otherwise occur in physician-patient relationships:27

‘If I see a patient from my culture and I have a similar background and [similar life] experiences, if I know their children and they [share my religious background] … I can refer to something I know about that they almost certainly heard in their childhood — like a scripture quotation — that addresses their specific issue right now; that will be very powerful.’27

Contextual factors

Visiting patients at the bedside or at home can facilitate spiritual discussions, because patients feel more at ease.26 Coworkers can also reinforce the GP's role in providing spiritual care.26

DISCUSSION

Summary

Many GPs see it as their role to identify and assess patients' spiritual needs, despite perceived barriers such as lack of time and specific training. However, they struggle with spiritual language and experience feelings of discomfort and fear that patients will refuse to engage in the discussion. Communicating willingness to engage in spiritual care, using a non-judgemental approach, facilitates spiritual conversations. Although GPs sometimes fear that patients will reject a spiritual discussion, many patients would like to be able to address spiritual concerns with their physicians if they become gravely ill,34 and seriously ill patients report wanting to be treated as ‘whole persons’ inclusive of spirituality.35,36

Strengths and limitations

This qualitative evidence synthesis is the first to collect and summarise the existing qualitative research about GPs' views on their role as spiritual care givers.

Although the number of publications reporting syntheses of qualitative research is rapidly increasing, little is known about which methods for synthesis are used and with what frequency, and how such syntheses deal with key challenges of review methodology, including methods for searching and appraisal.37 Elliott stated that a move towards improved explicitness about reporting of syntheses of qualitative research could take place ahead of a consensus emerging on methods for synthesis.38 The authors have therefore documented their methods carefully, and shown explicitness about the methods used for searching, appraisal, and synthesis.

It could be argued that ‘critical appraisals’ of the type used in quantitative syntheses are less appropriate for syntheses of qualitative evidence, where the purpose of the synthesis is more likely to be oriented towards maximising the conceptual yield of included papers rather than determining the robustness of the study design so that sensitivity analyses can be conducted.37 However, it was decided to perform a critical appraisal to avoid the possibility that studies of poor quality would influence the results of the synthesis.

After the line-by-line coding of the text, themes were identified based on their significance related to answering the research questions. Since this significance is a subjective interpretation of the authors, this could be a limitation of the study. It is not possible to guarantee that all aspects mentioned by GPs have entered the final results section.

Comparison with existing literature

Most GPs said that they indirectly provide spiritual care by actively listening to their patients' needs and being present with them. The question arises as to whether this is really spiritual care, or rather good communication skills. It is evident that spiritual care is grounded in the patient-centred care theoretical framework, in which the focus of care is on the patient and their experience of illness, as opposed to a sole focus on the disease. However, this is not the only dimension of spiritual care. Another model in which spiritual care is grounded is the biopsychosocial-spiritual model of care,39,40 based on a philosophical anthropology, a cornerstone of which is the concept of the person as a being-in-relationship. Disease can be understood as a disturbance in the right relationships that constitute the unity and integrity of what we know to be a human being. Humans are intrinsically spiritual since all persons are in relationship with themselves, others, nature, and the significant or sacred.11 The authors believe that a spiritual care giver should thus not only listen to the patient and be present with him or her, but also explore the dimension of the patient's relationships, and any disturbances in them.

Implications for research and practice

According to recent guidelines, and in line with the biopsychosocial-spiritual model of care, all trained healthcare professionals should carry out spiritual screening and history-taking.11 Spiritual screening or triage is a quick determination of whether a person is experiencing a serious spiritual crisis and therefore needs an immediate referral to a professional spiritual care giver Spiritual history-taking is the process of interviewing a patient in order to come to a better understanding of their spiritual needs and resources.11 Spiritual issues may be of special consequence at the end of life, with an increased questioning and search for meaning.41 Despite these recommendations, it may be too early for many GPs to implement them in practice.

Formal education in spirituality and health has only recently started to develop, so that most GPs have not yet received any spiritual education.

Research is needed to clarify the role of the GP as a spiritual care giver, and to evaluate the implementation of the existing outpatient spiritual care models. Research is also needed to evaluate formal education programmes in spirituality and health in the healthcare professions, as well as postgraduate education programmes.

This qualitative evidence synthesis has summarised GPs' views about spiritual care. The results of the studies included here were mostly congruent, affirming that many GPs see themselves as supporters of patients' spiritual wellbeing, especially in end-of-life care. However, they lack specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes to respond to the spiritual needs of their patients. Future research is needed to develop and implement a model of spiritual care in general practice that supports the GP in this delicate task, and that leads to improvements in the spiritual wellbeing of the patient.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Scott Murray, MD, FRCGP, FRCPEd, University of Edinburgh, for the recommendation of some relevant publications.

Appendix 1.

The Joanna Briggs Institute (jbi) tool

| Yes | No | Unclear | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. There is congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology. | |||

| 2. There is congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives. | |||

| 3. There is congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data. | |||

| 4. There is congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data. | |||

| 5. There is congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results. | |||

| 6. There is a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically. | |||

| 7. The influence of the researcher on the research, and vice versa, is addressed. | |||

| 8. Participants, and their voices, are adequately represented. | |||

| 9. The research is ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, there is evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body. | |||

| 10. Conclusions drawn in the research report do appear to flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data. | |||

| TOTAL | |||

| Inclusion | |||

Funding

The authors of the End-of-Life Research Group from the Academic Center of General Practice, KU Leuven, Belgium, are deeply grateful to the Chair Constant van De Wiel for the financial support that made this project possible.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have support from KU Leuven and Radboud University Nijmegen for the submitted work; the authors have no relationships with companies that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; their spouses, partners, or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and the authors have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Cancer pain relief and palliative care. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1990;804:1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinclair S, Pereira J, Raffin S. A thematic review of the spirituality literature within palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(2):464–479. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simington JA. Ethics for an evolving spirituality. In: Storch J, Rodney P, Starzomski R, editors. Toward a moral horizon: nursing ethics for leadership and practice. Toronto: Pearson-Prentice Hall; 2004. pp. 465–484. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright KB. Professional, ethical, and legal implications for spiritual care in nursing. Image J Nurs Sch. 1998;30(1):81–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1998.tb01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: research findings and implications for clinical practice. South Med J. 2004;97(12):1194–1200. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146489.21837.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bessinger D, Kuhne T. Medical spirituality: defining domains and boundaries. South Med J. 2002;95(12):1385–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belcher AE. Should oncology nurses provide spiritual care? ONS News. 2006;21(5):9–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonas-Simpson C. Jean Watson's caring science as sacred science: An important contribution to human science nursing in the 21st century. Nurs Sci Q. 2007;20(4):383–384. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moss EL, Dobson KS. Psychology, spirituality, and end-of-life care: an ethical integration? Can Psychol. 2006;47(4):284–299. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodge DR. A template for spiritual assessment: a review of the JCAHO requirements and guidelines for implementation. Soc Work. 2006;51(4):317–326. doi: 10.1093/sw/51.4.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the consensus conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(10):885–904. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sloan RP, Bagiella E, Powell T. Religion, spirituality, and medicine. Lancet. 1999;353(9153):664–667. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07376-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sloan RP, Bagiella E, VandeCreek L, et al. Should physicians prescribe religious activities? N Engl J Med. 2000;342(25):1913–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Post SG, Puchalski CM, Larson DB. Physicians and patient spirituality: Professional boundaries, competency, and ethics. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(7):578–583. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-7-200004040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gundersen L. Faith and healing. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(2):169–172. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-2-200001180-00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marwick C. Should physicians prescribe prayer for health — spiritual aspects of well-being considered. JAMA. 1995;273(20):1561–1562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sulmasy DP. Is medicine a spiritual practice? Acad Med. 1999;74(9):1002–1005. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199909000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellis MR, Campbell JD. Patients' views about discussing spiritual issues with primary care physicians. South Med J. 2004;97(12):1158–1164. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146486.69217.EE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lucas PJ, Baird J, Arai L, et al. Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretative synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hannes K, tCQMG Critical appraisal of qualitative research. http://www.jbiconnect.org/tools/cqrmg/documents/Cochrane_Guidance/Chapter6_Guidance_Critical_Appraisal.pdf (accessed 3 Oct 2011)

- 22.Morse JM, Barett M, Mayan M, et al. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Meth. 2002;1(2):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hannes K, Lockwood C, Pearson A. A comparative analysis of three online appraisal instruments' ability to assess validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(12):1736–1743. doi: 10.1177/1049732310378656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute-tool. http://www.jbiconnect.org/tools/cqrmg/tools_3.html (accessed 3 Oct 2011)

- 26.Ellis MR, Campbell JD, Detwiler-Breidenbach A, Hubbard DK. What do family physicians think about spirituality in clinical practice? J Fam Pract. 2002;51(3):249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellis MR, Campbell JD. Concordant spiritual orientations as a factor in physician-patient spiritual discussions: a qualitative study. J Relig Health. 2005;44(1):39–53. doi: 10.1007/s10943-004-1144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. General practitioners and their possible role in providing spiritual care: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(497):957–959. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanyi RA, McKenzie M, Chapek C. How family practice physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants incorporate spiritual care in practice. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21(12):690–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly B, Varghese FT, Burnett P, et al. General practitioners' experiences of the psychological aspects in the care of a dying patient. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6(2):125–131. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olson MM, Sandor MK, Sierpina VS, et al. Mind, body, and spirit: family physicians' beliefs, attitudes, and practices regarding the integration of patient spirituality into medical care. J Relig Health. 2006;45(2):234–247. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grant E, Murray SA, Kendall M, et al. Spiritual issues and needs: perspectives from patients with advanced cancer and nonmalignant disease. A qualitative study. Palliat Support Care. 2010;2(4):371–388. doi: 10.1017/s1478951504040490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colaizzi PF. Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In: Valle RS, King M, editors. Existential phenomenological alternatives for psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1978. pp. 48–71. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ehman JW, Ott BB, Short TH, et al. Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(15):1803–1806. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hart A, Jr, Kohlwes RJ, Deyo R, et al. Hospice patients' attitudes regarding spiritual discussions with their doctors. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20(2):135–139. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sered S, Tabory E. ‘You are a number, not a human being’: Israeli breast cancer patients' experiences with the medical establishment. Med Anthropol Q. 1999;13(2):223–252. doi: 10.1525/maq.1999.13.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dixon-Woods M, Booth A, Sutton AJ. Synthesizing qualitative research: a review of published reports. Qual Res. 2007;7(3):375–422. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elliott J. Using narrative in social research: qualitative and quantitative approaches. London: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnum BS. Spirituality in nursing: from traditional to new age. New York, NY: Springer; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sulmasy DP. Abiopsychosocial-spiritual model forthe care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist. 2002;42(Spec No 3):24–33. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards A, Pang N, Shiu V, Chan C. The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: a meta-study of qualitative research. Palliat Med. 2010;24(8):753–770. doi: 10.1177/0269216310375860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]