Abstract

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common gastrointestinal emergency, with peptic ulcer as the most common cause. Appropriate resuscitation followed by early endoscopy for diagnosis and treatment are of major importance in these patients. Endoscopy is recommended within 24 h of presentation. Endoscopic therapy is indicated for patients with high-risk stigmata, in particular those with active bleeding and visible vessels. The role of endoscopic therapy for ulcers with adherent clots remains to be elucidated. Ablative or mechanical therapies are superior to epinephrine injection alone in terms of prevention of rebleeding. The application of an ulcer-covering hemospray is a new promising tool. High dose proton pump inhibitors should be administered intravenously for 72 h after endoscopy in high-risk patients. Helicobacter pylori should be tested for in all patients with peptic ulcer bleeding and eradicated if positive. These recommendations have been captured in a recent international guideline.

Keywords: Peptic ulcer, Ulcer bleeding, Endoscopy, Management, Pharmacotherapy, Review

Introduction

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is the most common gastrointestinal emergency, with peptic ulcer bleeding (PUB) responsible for 31% to 67% of all cases, followed by erosive disease (7% to 31%) and variceal bleeding (4% to 20%). Less frequent causes are oesophagitis, Mallory Weiss tears and neoplasm [1–6]. Peptic ulcer bleeding is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality, which in various series range between 5% and 13% [5]. The risk of mortality strongly depends on age, the presence of comorbidity, the severity of the bleed, and the occurrence of rebleeding [6]. Comorbidity as risk determinant explains why in-patients with a bleeding episode have higher mortality rates than out-patients presenting at the emergency unit. Endoscopy and pharmacotherapy have become the mainstay in the management of PUB. Endoscopy allows both identification of the bleeding focus, classification of the risk of rebleeding, and application of treatment in the same session, whereas pharmacotherapy in particular aims at clot stabilization and ulcer healing by profound acid suppression. This review provides an update on the endoscopic management of peptic ulcer bleeding.

Risk Assessment and Pre-Endoscopic Management

Pre-Endoscopic Resuscitation

Immediate evaluation and initiation of appropriate resuscitation by means of administration of IV fluids, oxygen and blood transfusion when needed are of major importance in patients presenting with UGIB. Red blood cell transfusions are, depending on the underlying condition and clinical presentation generally administered once the hemoglobin level drops below 70 g/L, but the impact of transfusion on rebleeding and mortality is unknown. In a Cochrane meta-analysis the effects of red blood cell transfusions in adults with UGIB were assessed [7]. A total of three randomized or quasi-randomized trials comparing red blood cell transfusion and standard care without red blood cell transfusion included 126 patients. Red blood cell transfusion was, in these studies, associated with more deaths (5% vs. 0%; 2 studies) and more rebleeds (38% vs. 4%; 1 study). However, the included trials were heterogeneous in treatment regimens and outcome parameters and had several methodological deficiencies, which implied that the results of the meta-analysis can only be used as a stimulus for further studies, but not for firm clinical guidelines. In a large recent UK study, data on 4441 patients with acute UGIB were collected. Patients who received transfusion within 12 h of presentation had a twofold increased rate of rebleeding (OR 2.26; 95% CI 1.76–2.90) and a 28% increase in mortality (OR 1.28; 95% CI 0.94–1.74) compared to those not early transfused. These results persisted after correction for the severity of the bleed using Rockall scores and haemoglobin concentrations at presentation, the results may have been biased by persistent differences in case mix between early transfused and non-transfused patients [8]. Prospective studies with a strict defined transfusion protocol are needed. In the meantime, the risks and benefits of red blood cell transfusion must be carefully weighted individually.

Pharmacotherapy Prior to Endoscopy

Intravenous administration of high dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) prior to endoscopy neutralizes pH and leads to stabilization of blood clots. Investigators from Hong Kong studied the effect of preemptive infusion of omeprazole administered as an 80-mg intravenous bolus followed by an 8-mg infusion per hour before endoscopy in 638 patients with UGIB. They found a significant reduction in the need for endoscopic therapy (19% vs. 28%, P = 0.007) with fewer active bleeds during endoscopy (6% vs. 15%, P = 0.01) and more ulcers with clean base (64% vs. 47%, P = 0.001) in the omeprazole-treated patients [9]. No effect was found on other major outcome parameters as the need for transfusion, rebleeding and mortality. Therefore, international guidelines remark that pre-endoscopic PPI therapy may be considered to downstage the bleeding site and decrease the need for endoscopic intervention, but that this should not delay endoscopy [10••].

Risk Assessment

Early risk assessment is crucial to determine the optimal timing of endoscopy, to define patients at highest risk of rebleeding, and to predict the need for other measures as administration of IV fluids, blood transfusion, and intensive care admission. For this purpose, several risk classification systems have been developed. Two frequently used scoring systems are the Blatchford score and the Rockall score [11, 12]. The latter contains a pre-endoscopic part, as well as a post-endoscopic component including the results of endoscopy. Both the Blatchford and Rockall scoring systems consider vital signs at presentation and comorbidity. The Blatchford score is more focused on symptoms (melena and/or syncope) and laboratory results (hemoglobin and urea) compared to the Rockall score, but does not consider age. A recent prospective cohort study comparing the validity and usefulness of these scoring systems concluded that the Blatchford score, but not the pre-endoscopic Rockall score, is useful for predicting low-risk patients who do not need therapeutic endoscopy and who may be suitable for outpatient management [13]. Disappointingly, the positive predictive value of both scores for the need for endoscopic intervention was low. This supports initiatives to adapt existing scorings systems or develop new, aiming for more precise risk stratification.

Time to Endoscopy

International consensus guidelines recommend early endoscopy within 24 h of presentation for patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding [10••]. Data from a nationwide UK survey of 6750 patients seen in 208 hospitals with UGIB show that this recommendation is not widely followed. Of patients deemed at high risk, only 55% received endoscopy within 24 h [4•]. A main reason for delayed endoscopy was the absence in half of the hospitals of a formal out of hours endoscopy rota or service with a consultant available on call.

Early endoscopy is safe and effective for all risk groups, allows timely diagnosis and treatment, reduces use of resources and length of hospital stay, and decreases the need for surgery [10••]. So far, no additional benefit from very early or urgent (<12 h) endoscopy was found compared with early endoscopy (<24 h) with respect to rebleeding, surgery or mortality [14, 15]. However, emergency endoscopy should be performed as soon as possible after hemodynamic stabilization in selective patients who are hemodynamically unstable or have massive hematemeses.

Endoscopic Therapy

Endoscopic Features and the Need for Therapy

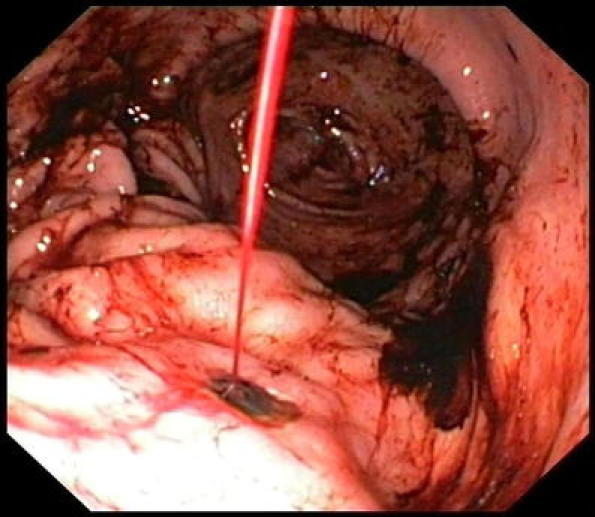

The endoscopic appearance of peptic ulcers provides important prognostic information and can identify ulcers as those with high versus low risk of rebleeding. Ulcers with signs of active spurting (Fig. 1) or oozing hemorrhage (resp. Forrest Ia and Ib) and ulcers with a visible vessel (Forrest IIa) are at high risk of recurrent bleeding with medical therapy alone. In contrast, ulcers with a clean base or flat spot in the ulcer bed (resp. Forrest III and IIc) do only rebleed in 4% to 13% of cases [16]. Ulcers with adherent clots have an intermediate risk of rebleeding (about 25%), depending on the underlying lesion. For that reason, clot removal should be attempted by vigorous irrigation.

Fig. 1.

Forrest Ia ulcer bleeding in a small gastric ulcer

Endoscopic haemostatic therapy is indicated for patients with high risk ulcers, while patients with low-risk stigmata can be treated with pharmacotherapy alone. The optimal management of bleeding peptic ulcers with adherent clot remains controversial. Two meta-analyses have addressed this issue. The first included six studies involving 240 patients from the United States, Southeast Asia, and Europe and found a significantly lower risk of rebleeding in the patients who underwent endoscopic therapy compared with the medical therapy group (8 vs. 25%, P = 0.01). The interventions yielded similar results with respect to the need for surgery, transfusion requirement, length of hospital stay and mortality [17]. The validity of this meta-analysis was however questioned since studies with heterogeneous designs were combined and most studies used suboptimal PPI dosage in the control group [18]. A more recent meta-analysis, including five trials, comprising 189 patients, found no significant benefit of endoscopic therapy in patients with ulcers with adherent clots [19•]. So far, endoscopic therapy should be considered, although intensive PPI therapy may be sufficient among patients with adherent clots resistant to vigorous irrigation.

Injection Therapy

Injection therapy with epinephrine is widely used for the treatment of PUB because it is inexpensive, easy to administer, and effective. Acute hemostasis is achieved by local tamponade, vasospasm, and induction of thrombosis. These effects resolve after about 20 min and it is therefore recommended to combine injection therapy with a more durable endoscopic technique [10••].

Other substances used in addition to or as an alternative to epinephrine are sclerosants (eg polidocanol, ethanolamine, and ethanol), fibrin sealant, and on some occasions n-butyl cyanoacrylate. However, the use of sclerosants for the treatment of PUB is nowadays limited, because they can cause serious local side-effects and in addition to epinephrine confer minimal additional benefit [20]. Fibrin sealant or glue is a relatively new agent for the treatment of PUB. It was shown to be more effective in preventing rebleeding than injection with polidocanol, but only if repeatedly injected [21]. Also, for that reason, it is not generally used in clinical practice. N-butyl cyanoacrylate is in particular used for gastric variceal bleeds, but is on rare occasions also applied to bleeding peptic ulcers with massive bleeds as a last resort, with the risk of arterial embolization [22].

Ablative and Mechanical Therapies

Several meta-analyses compared the effects of mechanical therapies (eg hemoclip placement), ablative therapy (eg heater probe and Gold probe), and injection therapy (eg epinephrine, fibrin glue and sclerosants) for hemostasis and prevention of rebleeding in peptic ulcer bleeding [19•, 23–26] (Table 1). This yielded two important messages. The first is that although epinephrine injection is more effective than acid suppressive therapy alone in patients with high risk stigmata, epinephrine monotherapy is inferior to other monotherapies as well as to combination therapy [19•, 23–25]. This means that epinephrine should no longer be applied as monotherapy, but only in combination with other methods. The second major message from the meta-analyses was that none of the ablative or mechanical therapies were superior over the others.

Table 1.

Recent meta-analyses comparing endoscopic techniques for treatment of peptic ulcer bleeding

| Author, year | No. trials included | No. patients included | Compared techniques | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marmo 2007 [23] | 20 | 2472 | Epinephrine injection +other injection or thermal or mechanical method vs. monotherapy with one of these methods | Dual endoscopic therapy is superior to epinephrine injection alone, but not to thermal or mechanical monotherapy |

| Sung 2007 [24] | 15 | 1156 | Hemoclips vs. injection/thermocoagulation | Hemoclip placement is superior to injection alone but comparable to thermocoagulation |

| Yuan 2008 [26] | 12 | 699 | Hemoclips vs. other endoscopic techniques | Hemoclip placement is not superior to other endoscopic modalities |

| Laine 2009 [19] | 65 | 6237 | Thermal devices, sclerosant, hemoclips, fibrin glue and epinephrine | Thermal devices, sclerosant, clips and fibrin glue are comparable. Epinephrine monotherapy is inferior to other interventions. |

| Barkun 2009 [25] | 41 | 4261 | Pharmacotherapy, injection, thermocoagulation, clips or combinations | All endoscopic therapies are superior to pharmacotherapy alone. Thermal therapy or clips alone or in combination with injection are comparable |

Dual therapy (ie epinephrine injection plus other injection or thermal or mechanical method) proved significantly superior to epinephrine injection alone, but had no advantage over thermal or mechanical monotherapy [23].

In specific situations, eg difficult-to-approach or indirectly visualized bleeding sites, heater probe therapy can be superior to hemoclip placement [27].

Hemospray

A potentially very important new development is the introduction of a hemospray which can be directly applied via a catheter through the working channel. This nanopowder with clotting abilities has been shown to be highly effective for achieving hemostasis of arterial bleeding in a heparinized animal model. When sprayed on a bleeding site, the powder becomes cohesive and adhesive, and forms a stable mechanical barrier, covering the bleeding site. In a very recent prospective pilot study on 20 adults with confirmed PUB (Forrest 1a or 1b), acute hemostasis was achieved in 95%. Rebleeding occurred in two patients (shown by hemoglobin drop), but no active bleeding was seen during repeat endoscopy in these patients. No mortality or adverse events were reported during 30-day follow-up [28•]. Further studies on the effectiveness of hemospray, also for other causes of UGIB, are ongoing.

Second Look Endoscopy

Few data support the overall benefit of a routine repeat endoscopy after endoscopic hemostasis. Those studies which did report a benefit from routine second look were in part of older date and did not include the use of PPIs or modern endoscopic haemostatic techniques. Therefore, second look endoscopy is not routinely recommended, however it may be beneficial in selected patients at high risk of rebleeding [10••, 29, 30].

Post-Endoscopic Management

Surgery or Angiographic Embolization

Although endoscopic therapy is highly effective, sometimes bleeding cannot be stopped or recurs. In case of recurrent bleeding a second attempt at endoscopic treatment is generally recommended [10••]. With persistent or renewed bleeding, emergency surgery and selective transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) of the bleeding artery are rescue modalities.

In a retrospective analysis of 70 cases with refractory PUB, no differences were found between patients treated with TAE versus surgery in the incidence of recurrent bleeding (29% vs. 23.1%), need for additional intervention (16.1% vs. 30.8%), or death (25.8% vs. 20.5). The lack of difference and the fact that the patients in the TAE group were older (75 year vs. 63 year, P < 0.001) and had more comorbidity, suggests a slight advantage of TAE [31]. There is a pressing need for randomized controlled trials to prospectively compare these two techniques.

Acid Suppressive Therapy

High dose intravenously administered PPI therapy (80 mg bolus, followed by 8 mg/h continuous infusion for 72 h) is recommended to reduce rebleeding in PUB patients with high-risk stigmata at endoscopy. This guideline recommendation is supported by a meta-analysis in which high dose IV PPI therapy significantly improved outcome compared with placebo/no therapy (RR, 0.40 [95% CI, 0.28-0.59]; NNT, 12 [95% CI, 10-18]) [19•]. In Asian patients, this beneficial effect has been achieved with different PPIs [32]. In Caucasian patients, who on average, have higher acid output, a significant effect on major outcome parameters such as rebleeding has only been achieved with high-dose continuous esomeprazole infusion [33]. Patients at low risk can be fed within 24 h and early discharged with oral PPI therapy.

Further Measures

In all patients, oral treatment with a PPI is generally recommended for 4 weeks, as this is sufficient to heal nearly all ulcers and address the underlying cause of the bleeding ulcer. Helicobacter pylori infection and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the main risk factors for the development of peptic ulcer disease. Therefore, every patient with a PUB should be tested for H. pylori and receive eradication therapy if applicable. Invasive tests obtained in the acute setting may yield false-negative results, and should thus be repeated in case they give no evidence of H. pylori infection [10••]. A total of 1 month after antimicrobial therapy, patients should be reassessed for successful eradication, as persistent H. pylori infection is associated with a more than 50% risk of recurrent ulcer disease within 2 years, and thus, with a significant risk for recurrent ulcer complications including bleeding [34].

Patients who develop PUB while on NSAID therapy, should be considered for permanent withdrawal of such therapy. If this is not feasible, they should preferentially switch to the combination of a selective COX2-inhibitor together with PPI gastroprotection since a COX2-inhibitor alone, as well as a conventional NSAID with a PPI are both associated with a persistent rebleeding risk [10••, 35]. The need for adequate adherence to the gastroprotective PPIs should be stressed, as various studies have now shown that even moderate lack of adherence significantly increases the risk of events [36, 37].

In patients who develop ulcer bleeding while on low dose aspirin, the need for this therapy should also be reassessed. In many, low dose aspirin is given for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. In these patients, continuation of antiplatelet treatment during the bleeding episode may increase rebleeding but reduces all-cause mortality rates. This was concluded by a recent RCT including 156 low-dose aspirin users for secondary cardiovascular prophylaxis. After endoscopic treatment for peptic ulcer bleeding, these patients were randomly assigned to either continue aspirin or receive placebo, both in combination with 72 h high dose IV PPI followed by an oral PPI for 8 weeks. The 30-day rebleeding rate was not significantly higher in the aspirin than in the placebo group (10.3 vs. 5.4%; Δ 4.9% [95% CI −3.6–13.4]), but the all-cause mortality (1.3% vs. 12.9%; Δ 11.6% [CI, 3.7–19.5%]) and the mortality rates attributable to cardiovascular, cerebrovascular or gastrointestinal complications (1.3% vs. 10.3% Δ 9% [CI, 1.7–16.3%]) were significantly lower in the aspirin group [38•]. Until now, no prospective studies have been performed to study shorter intervals of discontinuation of aspirin. The optimal period of discontinuation is thus not yet defined. For now, guidelines recommend to restart aspirin 3 to 5 days after endoscopic therapy, provided that the patients hemodynamic condition is stable [29].

Patients with idiopathic ulcer disease, ie those in whom adequate assessment does not reveal an underlying cause, should also be treated with PPI maintenance therapy as they are at considerable risk for recurrent ulcer formation and bleeding [39].

Future Research

In the past 2 decades, major developments took place in the management of peptic ulcer bleeding. Proton pump inhibitors were introduced, H. pylori was recognized as an important risk factor for the development of peptic ulcers, and endoscopic therapy had become the main therapy for the majority of patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. Despite these valuable new discoveries, PUB incidence remained stable and probably will even rise in the near future due to aging of the population accompanied by increasing use of medication and comorbid illness.

Therefore, there is a pressing need for studies to elucidate the optimal time to endoscopy, the optimal approach to patients with adherent clots, the most effective endoscopic techniques and the best alternative for patients refractory to endoscopic therapy. In addition, development of an appropriate risk stratification scorings system and safe transfusion policy will be important topics for future research.

Conclusions

Peptic ulcer bleeding is the most frequent emergency condition in gastroenterology practice. It is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Endoscopy is the mainstay in the modern management of PUB. Ideally endoscopy should be performed within 24 h of presentation. Combination therapy of epinephrine injection plus another hemostatic technique or the use of another hemostatic technique alone is more effective than epinephrine alone. Hemospray is a new promising endoscopic therapy. Patients with high-risk stigmata should receive continuous IV PPI administration for 72 h after endoscopy. After the acute phase, the underlying cause of the ulcer should be verified and treated when possible.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

Ernst J. Kuipers has been an advisory board member, consultant and grant recipient for AstraZeneca; Ingrid L. Holster reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Ingrid Lisanne Holster, Email: i.holster@erasmusmc.nl.

Ernst Johan Kuipers, Email: e.j.kuipers@erasmusmc.nl.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •Of importance ••Of major importance

- 1.van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1494–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Fiore F, Lecleire S, Merle V, et al. Changes in characteristics and outcome of acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: a comparison of epidemiology and practices between 1996 and 2000 in a multicentre French study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:641–7. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200506000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theocharis GJ, Thomopoulos KC, Sakellaropoulos G, et al. Changing trends in the epidemiology and clinical outcome of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a defined geographical area in Greece. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:128–33. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000248004.73075.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hearnshaw SA, Logan RF, Lowe D, et al. Use of endoscopy for management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: results of a nationwide audit. Gut. 2010;59:1022–1029. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.174599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czernichow P, Hochain P, Nousbaum JB, et al. Epidemiology and course of acute upper gastro-intestinal haemorrhage in four French geographical areas. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:175–81. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paspatis GA, Matrella E, Kapsoritakis A, et al. An epidemiological study of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Crete, Greece. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:1215–20. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012110-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jairath V, Hearnshaw S, Brunskill SJ, et al.: Red cell transfusion for the management of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD006613. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hearnshaw SA, Logan RF, Palmer KR, et al. Outcomes following early red blood cell transfusion in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:215–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau JY, Leung WK, Wu JC, et al. Omeprazole before endoscopy in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1631–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101–113. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, et al. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316–21. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 2000;356:1318–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pang SH, Ching JY, Lau JY, et al. Comparing the Blatchford and pre-endoscopic Rockall score in predicting the need for endoscopic therapy in patients with upper GI hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1134–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schacher GM, Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Ortner MA, et al. Is early endoscopy in the emergency room beneficial in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer? A “fortuitously controlled” study. Endoscopy. 2005;37:324–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-826237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Targownik LE, Murthy S, Keyvani L, et al. The role of rapid endoscopy for high-risk patients with acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:425–9. doi: 10.1155/2007/636032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cappell MS. Medscape. Therapeutic endoscopy for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:214–29. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahi CJ, Jensen DM, Sung JJ, et al. Endoscopic therapy versus medical therapy for bleeding peptic ulcer with adherent clot: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:855–62. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laine L: Systematic review of endoscopic therapy for ulcers with clots: Can a meta-analysis be misleading? Gastroenterology. 2005, 129:2127; author reply 2127–2128. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Laine L, McQuaid KR. Endoscopic therapy for bleeding ulcers: an evidence-based approach based on meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung SC, Leong HT, Chan AC, et al. Epinephrine or epinephrine plus alcohol for injection of bleeding ulcers: a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:591–5. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(96)70197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutgeerts P, Rauws E, Wara P, et al. Randomised trial of single and repeated fibrin glue compared with injection of polidocanol in treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer. Lancet. 1997;350:692–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)03233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurokohchi K, Maeta T, Ohgi T, et al. Successful treatment of a giant exposed blood vessel in a gastric ulcer by endoscopic sclerotherapy with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. Endoscopy. 2007;39(Suppl 1):E250. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-967012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marmo R, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, et al. Dual therapy versus monotherapy in the endoscopic treatment of high-risk bleeding ulcers: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:279–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Lai LH, et al. Endoscopic clipping versus injection and thermo-coagulation in the treatment of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2007;56:1364–73. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.123976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barkun AN, Martel M, Toubouti Y, et al. Endoscopic hemostasis in peptic ulcer bleeding for patients with high-risk lesions: a series of meta-analyses. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:786–99. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan Y, Wang C, Hunt RH. Endoscopic clipping for acute nonvariceal upper-GI bleeding: a meta-analysis and critical appraisal of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:339–51. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.03.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin HJ, Perng CL, Sun IC, et al. Endoscopic haemoclip versus heater probe thermocoagulation plus hypertonic saline-epinephrine injection for peptic ulcer bleeding. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:898–902. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sung JJ, Luo D, Wu JC, et al. Early clinical experience of the safety and effectiveness of Hemospray in achieving hemostasis in patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Endoscopy. 2011;43:291–295. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sung JJ, Chan FK, Chen M, et al.: Asia-Pacific Working Group consensus on non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Chiu PW, Joeng HK, Choi CL, et al. Predictors of peptic ulcer rebleeding after scheduled second endoscopy: clinical or endoscopic factors? Endoscopy. 2006;38:726–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ripoll C, Banares R, Beceiro I, et al. Comparison of transcatheter arterial embolization and surgery for treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer after endoscopic treatment failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:447–50. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000126813.89981.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leontiadis GI, Sharma VK, Howden CW. Systematic review and meta-analysis: enhanced efficacy of proton-pump inhibitor therapy for peptic ulcer bleeding in Asia–a post hoc analysis from the Cochrane Collaboration. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1055–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sung JJ, Barkun A, Kuipers EJ, et al. Intravenous esomeprazole for prevention of recurrent peptic ulcer bleeding: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:455–64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-7-200904070-00105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gisbert JP, Khorrami S, Carballo F, et al. Meta-analysis: Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy vs. antisecretory non-eradication therapy for the prevention of recurrent bleeding from peptic ulcer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:617–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan FK, Wong VW, Suen BY, et al. Combination of a cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitor and a proton-pump inhibitor for prevention of recurrent ulcer bleeding in patients at very high risk: a double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369:1621–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60749-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Soest EM, Sturkenboom MC, Dieleman JP, et al. Adherence to gastroprotection and the risk of NSAID-related upper gastrointestinal ulcers and haemorrhage. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:265–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Soest EM, Valkhoff VE, Mazzaglia G, et al.: Suboptimal gastroprotective coverage of NSAID use and the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and ulcers: an observational study using three European databases. Gut. 2011, In press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ching JY, et al. Continuation of low-dose aspirin therapy in peptic ulcer bleeding: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;152:1–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong GL, Wong VW, Chan Y, et al. High incidence of mortality and recurrent bleeding in patients with Helicobacter pylori-negative idiopathic bleeding ulcers. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:525–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]