Abstract

A study examining the effects of terrorism on a national sample of 1,136 Jewish adults was conducted in Israel via telephone surveys, during the Second Intifada. The relationship between reports of positive changes occurring subsequent to terrorism exposure (i.e., Benefit finding), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom severity, and negative outgroup attitudes toward Palestinian citizens of Israel (PCI) was examined. Benefit finding was related to greater PTSD symptom severity. Further, Benefit finding was related to greater threat perception of PCI and ethnic exclusionism of PCI. Findings were consistent with hypotheses derived from theories of outgroup bias and support the anxiety buffering role of social affiliation posited by terror management theory. This study suggests that benefit finding may be a defensive coping strategy when expressed under the conditions of ongoing terrorism and external threat.

The Al Aqsa Intifada, a period of ongoing terrorism, began in 2000 and at the time of this study, had resulted in more than 1,000 civilian deaths and 4,511 injuries in Israel resulting from multiple acts of terrorist violence (National Security Studies Center Terrorism Database, 2005). In a nationally representative sample, almost half of Israelis were found to be directly exposed or indirectly exposed through a friend or family member to terrorism (Bleich, Gelkopf, & Solomon, 2003). For most, the threat of terror is an inescapable part of the Israeli condition and the reality of threat to the safety of self and loved-ones is omnipresent. Recent interest has focused on the tendency for many individuals to find benefit amidst tragedy (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004; McMillen, Smith, & Fisher, 1997; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995). This study examines self-reported growth experiences (i.e., benefit finding) in response to recent and ongoing direct and indirect exposure to terrorism and its relationship to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom severity and negative out-group attitudes. We explore benefit finding as a defensive process within the context of ongoing terrorism by utilizing prevailing social psychological theories regarding intergroup dynamics.

BENEFIT FINDING: A MULTI-DIMENSIONAL CONSTRUCT

Recent studies have demonstrated the negative psychological effects of terrorism (Bleich et al., 2003; Galea et al., 2002; Hall et al., 2008; Hobfoll, Canetti-Nisim, & Johnson, 2006; Schlenger et al., 2002; Schuster et al., 2001; Silver, Holman, McIntosh, Poulin, & Gil-Rivas, 2002). However, an emerging literature suggests that people can derive benefits from their traumatic experiences (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004; Linley & Joseph, 2004; McMillen et al., 1997; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995). The overarching process of growing and finding benefits following untoward life events has been called stress-related growth (Park, Cohen, & Murch, 1996) adversarial growth (Linley & Joesph, 2004), and posttraumatic growth (PTG; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995). The common element of all of these constructs is that a change is reported that is construed as positive and steaming from having experienced a stressful life event. For the purpose of inclusiveness and in accord with Helgeson, Reynolds, and Tomich (2006), we adopt the term benefit finding to account for the process of reporting positive changes subsequent to terrorism.

Benefit finding is a multidimensional construct involving both interpersonal and intrapersonal dimensions. One of the most comprehensive models for studying this process was articulated by Tedeschi and Calhoun (1995). These authors conceptualized PTG as changes in self-perception, interpersonal relationships, and philosophy of life (e.g., meaning and purpose). Furthermore, PTG has been formulated as gaining more than simply returning to baseline functioning following a traumatic event, but it is rather characterized as achieving an enhanced level of functioning, sense of meaning or spirituality, and developing closer relationships that were not present before the traumatic event occurred (Linley & Joseph, 2004; O’Leary & Ickovics, 1995). Recently, PTG has also been linked to participation in political demonstrations (Paez, Basabe, Ubillos, & Gonzalaz-Castro, 2007). By rallying behind a political cause people may achieve enhanced in-group cohesion as another dimension of PTG.

BENEFIT FINDING AND PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS

Studies exploring the relationship between benefit finding and psychopathology have demonstrated inconsistent results (see Helgeson et al., 2006 or Linley & Joseph, 2004 for a review). Some studies have found benefit finding to relate with lower psychological distress (Frazier, Conlon, & Glaser, 2001), whereas other studies found benefit finding related to greater psychological distress (Elder & Clipp, 1988; Lehman et al., 1993; Park et al., 1996; Tomich & Helgeson, 2004; Wild & Paivio, 2003). Still other studies found benefit finding and psychological distress to be orthogonal (Val & Linley, 2006).

Several studies have specifically explored the relationship between benefit finding and psychological distress following terrorism (Ai, Cascio, Santangelo, & Evans-Campbell, 2005; Butler et al., 2005; Hobfoll, Canetti-Nisim, et al., 2006; Val & Linley, 2006). Ai and colleagues (2005) found that hope and spiritual meaning following September 11, 2001 was related to less depression and anxiety symptom severity in a sample of college students. In a large-scale internet-based study, Butler et al. (2005) found that initial reports of benefit finding were related to greater symptoms of PTSD. In this same study, a curvilinear relationship was found between PTSD and benefit finding such that benefit finding was related to moderate levels of PTSD symptom severity. Hobfoll, Canetti-Nisim, et al. (2006) found that benefit finding was associated with more PTSD and depressive symptom severity in an Israeli sample. Laufer and Solomon (2006) found reports of benefit finding were related to greater psychological distress in a sample of Israeli adolescents who were directly and indirectly exposed to terrorism. In contrast, Val and Linley (2006) examined benefit finding within a sample of Madrid residents indirectly exposed to the March 11, 2004 Madrid train bombings; they found no relationship between benefit finding and depression, or anxiety symptom severity.

These mixed findings in the few studies of terrorism-related benefit finding suggest that a reduction in distress is not necessarily a concomitant reaction to reporting benefits accrued as a result of terrorism exposure. Therefore further studies are warranted to explore the relationship between benefit finding and psychological distress for people exposed to terrorism.

The literature on benefit finding is relatively new, and growing, and the question whether benefit finding is beneficial (i.e., is related to fewer symptoms of distress) for some but not others still remains largely unresolved, especially for people who have experienced terrorism. The results of a recent meta-analysis of 77 cross-sectional studies (Helgeson et al., 2006) found that benefit finding was related to greater avoidance and intrusive thoughts, core features of PTSD. This study also synthesized findings regarding factors that moderate the relationship between benefit finding and psychological distress, albeit for those experiencing mostly health-related traumatic events.

Studies have generally shown that benefit finding was related to less anxiety when fewer than two years elapsed from the time the traumatic event occurred (Helgeson et al., 2006). Whether benefit finding has differential effects for men or women remains inconsistent in the literature, and is often confounded by the type of trauma experienced (e.g., women are more likely to report rape trauma). Given that terrorism is a community-wide trauma, it provides an opportunity to test sex as a moderator without the sex-by-event confounding. Age (i.e., being older) and religiosity (i.e., being more religious) have also been linked to greater reports of benefit finding (Helgeson et al., 2006), but their role as moderators of a relationship between benefit finding and PTSD have not been sufficiently explored. Variables associated with socioeconomic status have been linked to reports of benefit finding (Butler et al., 2005; Tomich & Helgeson, 2004) and with psychological distress following terrorism exposure (Hobfoll, Tracy, & Galea, 2006). As yet, education and income have not been tested as potential moderators of the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and benefit finding. In addition, a trauma such as terrorism exposes people in direct and indirect ways (e.g., directly through injury to self, or indirectly through loss or injury to family and friends). Whether benefit finding may relate to less psychological distress in either, or both cases, remains of particular interest, especially in light of the research linking the development of PTSD symptoms following both types of exposure (Galea, et al., 2002; Schlenger et al., 2002; Schuster et al., 2001; Silver, et al., 2002). Examining moderators that may explain the variation in findings between benefit finding and PTSD symptom severity is important in order to ascertain for whom and in what circumstances benefit finding may serve a salutogenic function (Zoellner & Maercker, 2006). Furthermore, it is important to understand whether enhanced feelings of social connectedness, personal strength, and meaning is related to attitudes toward outgroups.

THE DEFENSIVE NATURE OF BENEFIT FINDING DURING ONGOING TERRORISM

Research has demonstrated that individuals prefer their own social group and exhibit biases toward members of outgroups. For example, in their minimal group paradigm, Tajfel, Billig, Bundy, and Flament (1971) showed that people who were randomly assigned to an arbitrary group demonstrated ingroup favoritism and bias toward outgroup members in the allocation of resources.

Within the context of trauma, and consistent with the benefit finding literature, people who are exposed to conflict exhibit a stronger sense of ingroup cohesion (Moskalenko, McCauley, & Rozin, 2006; Stein, 1976). In a naturalistic experiment of a sample of college students, Moskalenko and colleagues (2007) found an increase in in-group identification following exposure to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. The authors suggested that forming closer bonds following a traumatic event could offer a modicum of control in response to an otherwise uncontrollable event. Indeed, the subjective uncertainty reduction model of social identity processes predicts that under conditions of low certainty, people in homogonous groups are better at reducing uncertainty and that people have a tendency to seek out similar others to reduce uncertainty (Grieve & Hogg, 1999; Jetten, Hogg, & Mullin, 2000; Mullin & Hogg, 1998).

The sense of group identification and cohesion that develops in response to trauma may lead to prejudicial attitudes toward out-groups. According to realistic group-conflict theory (Campbell, 1965; Sherif, 1966), negative interdependence (e.g., competition for resources) between groups leads to intergroup threat which in turn leads to negative outgroup attitudes (Jackson, 1993). The long-term struggle between Jewish Israelis and Palestinians is exemplary of such a zero-sum condition that gives rise to these attitudes (see Kelman, 1999 for a review). People who are exposed to threat from out-group members exhibit an increase in biases toward members of that outgroup.

Terror management theory (Greenberg, Pyszczynski, & Solomon, 1986) offers a compelling theoretical framework from which to make predictions about how benefit finding may be related to negative outgroup attitudes. Terror management theory posits that humans are endowed intellectually with the ability to identify the inevitability of their own death and nonexistence (Becker, 1973; Greenberg et al., 1986) and that this foreknowledge increases the potential for existential terror and anxiety. This terror is thought to be assuaged through dual anxiety buffering processes of maintaining allegiance to cultural worldviews and gaining enhanced self-esteem through behaviors consonant with the standards of one’s worldview (Rosenblatt, Greenberg, Solomon, Pyszczynski, & Lyon, 1989). Of particular importance to our current discussion, culture lessens this terror through worldviews that “consist of humanly constructed beliefs about reality shared by individuals in groups that provide a sense that one is a person of value in a world of meaning” (Solomon, Greenberg, & Pyszczynski, 2004, p. 17). In this manner, individuals may assuage this sense of terror by finding greater meaning in their worldview (i.e., worldview defense) and by adhering more closely to those who support them and their views (Castano, Yzerbyt, Paladino, & Sacchi, 2002; Castano & Dechesne, 2005; Rosenblatt et al., 1989; Wisman & Koole, 2003). Similarly, studies have shown that terror salience (i.e., the affect of being made aware of the occurrence of terrorism) increases participant defense of social order as measured by increased punishment for those who violate criminal laws (Fischer, Greitemeyer, Kastenmüller, Frey, & Oßwald, 2007).

In the laboratory, mortality salience—being reminded of the inevitability of one’s death and nonexistence, typically elicited through an experimental manipulation of asking participants to write about their own death—has been shown to heighten the motivation to form and maintain close relationships (Castano & Dechesne, 2005; Mikulincer, Florian, & Hirschberger, 2003) and has increased negative reactions toward members of outgroups perceived as threatening to participants or their cultural worldviews (Halloran & Kashima, 2004; Hirschberger, 2006; McGregor et al., 1998; Rosenblatt et al., 1989; Simon, Arndt, Greenberg, Pyszczynski, & Solomon, 1998). Research has also implicated mortality salience in increasing stereotyping of outgroup members (Schimel et al., 1999). Recent studies conducted in the United States and Iran (Pyszczynski et al., 2006), and in Israel (Hirschberger & Ein-Dor, 2006), have demonstrated that priming mortality salience also increases the support for violence against members of outgroups.

These findings mirror the real-world events that followed the September 11th terrorist attacks as people engaged in behavior that demonstrated increased patriotism, the result of which was to reaffirm faith in the “American Way of Life” (Pyszczynski, Solomon, & Greenberg, 2003). At the same time, events unfolded whereby people from other countries or different ethnicities, perceived as outgroup members, were threatened or attacked (Huddy, Khatid, & Capelos, 2002; Jacoby, 2001).

Within the context of ongoing threat and terrorism, benefit finding may function as a measure of the ingroup cohesion that follows outgroup threat (Castano & Dechesne, 2005; Jackson, 1993). This would lead to the prediction that benefit finding may enhance people’s sense of closeness to others, but may also yield negative consequences when one considers the potential emergence of negative outgroup attitudes. In this way, benefit finding may be a manifestation of a defensive process that people use to cope with traumatic events that are outside of their control (Mullin & Hogg, 1998).

The aims of this study were twofold. The first aim was to explore the relationship between benefit finding and PTSD symptom severity, while examining several variables that may moderate this relationship (Helgeson et al., 2006). The second aim of the study was to test the hypothesized relationship between benefit finding and negative outgroup attitudes. We hypothesized that benefit finding serves a defensive function through the perception of enhanced in-group cohesion and intrapersonal benefits gained subsequent to the trauma of terrorism. Therefore, we predicted that benefit finding would be related to greater negative outgroup attitudes consistent with the theories of intergroup processes we reviewed.

METHODS

DATA COLLECTION AND SAMPLING

A nationally representative sample of Israelis was randomly surveyed. Phone interviews were conducted between August 17th and September 8th, 2004 by a survey institute in Israel using a structured questionnaire that was carefully pilot-tested and used in prior studies (Hobfoll, Canetti-Nisim et al., 2006). All scales were translated and back translated by language experts and it was completed by participants in 30–40 minutes. Initial contact was made by a Hebrew speaker; Russian speakers were available if individuals did not speak Hebrew, and callbacks were arranged within 24 hours if a Russian speaker was not immediately available. Fifteen attempts were made to contact an adult at each telephone number. At the onset of the interview, oral informed consent was obtained. Mental health referrals were made if interviewees requested such a referral or became upset during the interview.

The response rate among eligible responders (those who qualified for the study) was estimated to be 57%. Of all potentially working numbers, 37% responded (i.e., not all working numbers had adult responders who spoke Hebrew or Russian). This compared favorably with studies in the U.S., especially given that the dialing methods in Israel, unlike the U.S., include business phones (approximately 10%) which are treated as a failed attempt and that the higher rates in U.S. studies typically do not include non-answered phones (Galea et al., 2002; Stuber, Galea, Boscarino, & Schlesinger, 2006).

Participation rates between 30% and 70% are weakly associated with bias, and any bias in sampling is addressed by examining the representativeness of the obtained sample (Galea & Tracy, 2007). There were no significant differences between the current sample and the 2003 Census in terms of sex, ethnicity, age, and education.

Participant demographics and the means, standard deviations, and percentages for the study variables appear in Table 1. The sample consisted of 1,136 Jewish adults; 534 men (47%) and 602 women (53%). Ages ranged from 18 to 96 years with a mean age of 45.38 (SD = 16.57). With regard to education, 39.9% had a college education, 23.6% had some post-high school education (or were in college), 32.1% reported high school as the highest level of educational attainment, and 3.7% had less than a high school education. In terms of religiosity, 64.3% considered themselves secular, 23.3% considered themselves traditional (following some practices), and 11.8% considered themselves religious. Nearly half of the sample reported experiencing indirect exposure (46.9%) and a little more than a quarter of the sample (25.8%) reported experiencing direct exposure to one or more terrorist events.

TABLE 1.

Percentages, Means, and Standard Deviations for Study Variables

| Variable | % | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 45.38 | 16.57 | 18 – 96 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 47 | |||

| Female | 53 | |||

| Education | ||||

| Elementary | 3.7 | |||

| High School | 32.1 | |||

| Some College | 23.6 | |||

| College Degree | 39.9 | |||

| Yearly Household Income | ||||

| Below Average | 34.4 | |||

| Average | 22.1 | |||

| Above Average | 33.1 | |||

| Religiosity | ||||

| Secular | 64.3 | |||

| Traditional | 23.3 | |||

| Religious | 11.8 | |||

| Exposed to Terrorism | ||||

| Direct | 25.8 | |||

| Indirect | 46.9 | |||

| Posttraumatic Growth | 3.36 | 3.67 | 0 – 12 | |

| PTSD Total Symptom Severity | 10.32 | 9.95 | 0 – 51 | |

| PTSD Intrusion Symptom Severity | 3.17 | 3.59 | 0 – 15 | |

| PTSD Avoidance Symptom Severity | 3.86 | 4.26 | 0 – 21 | |

| PTSD Hyperarousal Symptom Severity | 3.30 | 3.56 | 0 – 15 | |

| Threat Perception of PCI | 10.33 | 5.15 | 3 – 18 | |

| Exclusion of PCI | 14.15 | 5.90 | 4 – 24 | |

Note. N = 1,136 Jewish adults; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; PCI = Palestinian citizens of Israel.

INSTRUMENTS

The questionnaire included measures of exposure to terrorism within the past 3 months, symptoms of PTSD, benefit finding, ethnic exclusionism of Palestinian citizens of Israel (PCI), and threat perception of PCI. Demographic information was obtained regarding participants’ age, sex, income, educational attainment, and religiosity.

Exposure to Terrorism

Participants were asked whether they had been exposed directly or indirectly to various terrorism-related events during the three months prior to the phone interview. We assessed direct exposure by asking whether the participant experienced a death of a family member or a friend, witnessed a terrorist attack or had been present at a site where there were injuries or fatalities, experienced an injury, or experienced a period of time when they did not know if someone close to them was killed or injured, but feared they might be. Indirect exposure was assessed by asking whether participants had to take bus routes or go to places that had been targets of attack, or if family had to take bus routes or go to places that had been targets of attack, or whether they happened to be at a place or on a bus route within 48 hours before it was the target of a terrorist attack or an act of war. Two separate dichotomous exposure variables were created, one each for direct and indirect exposure to terrorism, where 0 indicated no exposure and 1 indicated exposure to one or more acts of terrorism. Both types of terrorism criteria for potentially traumatic events that exposure satisfy the A1 could lead to a diagnosis of PTSD as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Benefit Finding

Four items, rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (extremely) from the COR-Evaluation (Hobfoll & Lilly, 1993) were used to assess benefit finding. To assess changes experienced since the Intifada, items were all prefaced with “As a result of the Intifada, I have …” The individual items were as follows: “greater intimacy with one or more family members,” “closer relationships with friends,” “greater feelings that my life has purpose,” and, “more confidence in my ability to do things.” Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was α =.77 in the current study. This short scale essentially captures positive benefits in the three domains of self-perception, interpersonal relationships, and philosophy of life posited by Tedeshi and Calhoun (1995) and has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties (α = .82) in studies previously conducted in Israel (Hobfoll et al., 2006). A recent reliability and validity study (Hall & Hobfoll, 2008) was conducted with 245 undergraduate students who reported experiencing a variety of traumatic and stressful life events to determine the relatedness between this brief scale and Tedeschi and Calhoun’s (1996) commonly used Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) which was also developed in an undergraduate sample of similar composition (i.e., similar in terms of age, ethnicity, and type of traumatic event exposure). The two scales were highly correlated (r = .85) indicating that they measure highly similar constructs. Within the current investigation, this brief 4-item scale measures the reported benefits that accrued during exposure to continuous and ongoing terrorism.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

PTSD symptom severity was measured using the posttraumatic stress disorder symptom scale, interview format (PSS-I; Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993). Participants reported on the severity of PTSD symptoms occurring for at least one month relating to experiences involving a terrorist attack. The PSS-I contains 17 items that assess PTSD symptom criteria based on the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Items were answered on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (extremely). PTSD symptoms were scored by summing the item responses. We also summed items to create the three PTSD subscales of reexperiencing (e.g., repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts, or images of the terrorist attacks), avoidance (e.g., avoiding thinking about or talking about the terrorist attacks) and hyperarousal (e.g., feeling jumpy or easily startled). Cronbach’s alpha for the full scale was .88, .76 for reexperiencing, .74 for avoidance, and .73 for hyper-arousal in the current study.

Variables Assessing Negative Outgroup Attitudes

To assess variables related to negative outgroup attitudes, we relied on two scales that measured participants’ attitudes toward PCI.

Threat Perception of PCI

This was assessed using a 3-item measure adapted from Shamir and Sullivan (1985). Items were answered on a scale from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree). Example items include “Arabs are dangerous to the security of Israel,” “Arabs are dangerous to the democracy in Israel.” Internal reliability for this scale was .86.

Attitudes Toward Ethnic Exclusionism of PCI

These were assessed using a 4-item scale. Items were answered on a scale from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 6 (very strongly agree). Example items include “All Arabs should leave the State of Israel,” “Arabs should not be allowed equal social rights as Jews.” The scale has been found to have broad, cross-cultural applicability in 15 countries (Scheepers, Gijsberts, & Coenders, 2002). Internal reliability for this scale was .86.

ANALYSES

Correlation and hierarchical linear regression analyses were conducted to explore the relationship between benefit finding and PTSD symptom severity. PTSD symptom severity was regressed on demographic variables, terrorism exposure, and benefit finding as these are theoretically relevant predictors of PTSD symptom severity.1 We thought it would also be important to test for a curvilinear relationship between benefit finding and PTSD symptom severity given that a curvilinear relationship between PTG and PTSD symptom severity was observed in a previous study of terrorism exposure (Butler et al., 2005). We also tested several moderators that may explain the relationship between benefit finding and PTSD symptom severity. Variables were entered in blocks in the following order: (1) age, sex, religiosity, education, income, (2) direct and indirect terrorism exposure, (3) benefit finding, (4) benefit finding squared, (5) the interaction between benefit finding and age, gender, religiosity, education, and income, and (6) the interaction between benefit finding and direct and indirect terrorism exposure. Interactions were calculated using centered variables (Aiken & West, 1991).

Next, we conducted hierarchical linear regression analyses to test the hypothesis that greater benefit finding would be related to greater attitudes of threat perception of PCI and ethnic exclusionism of PCI. We thought it would be theoretically instructive to test for a curvilinear relationship between PTSD symptom severity and the report of negative outgroup attitudes. Results indicating a curvilinear relationship between these constructs could suggest that terror management processes are disrupted as PTSD symptom severity increases. We also tested the interaction between benefit finding and PTSD symptom severity to determine whether PTSD symptom severity moderated this hypothesized relationship. Furthermore we tested interactions between direct and indirect terrorism exposure and benefit finding to examine whether exposure to terrorism moderated the relationship between benefit finding and negative outgroup attitudes. In all cases, interaction terms were created using centered variables (Aiken & West, 1991). Variables were entered in blocks in the following order: (1) age, sex, religiosity, education, income, (2) direct and indirect terrorism exposure, (3) PTSD symptom severity, (4) PTSD symptom severity squared, (5) benefit finding, (6) the interaction between PTSD symptom severity and benefit finding, and (7) the interaction between benefit finding and direct and indirect terrorism exposure.

RESULTS

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BENEFIT FINDING AND PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS

Table 2 shows the results of correlation analyses. Benefit finding was significantly and positively related to greater overall PTSD symptom severity and greater symptom severity across each of the three PTSD symptom clusters.

TABLE 2.

Intercorrelation Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | — | |||||||||||||

| 2. Sex (Female) | −.01 | — | ||||||||||||

| 3. Religiosity | −.13** | .09** | — | |||||||||||

| 4. Education | .07* | .08* | −.14** | — | ||||||||||

| 5. Income | −.12** | −.11** | −.15** | .18** | — | |||||||||

| 6. Recent Direct Terrorism Exposure | .04 | .04 | .01 | .00 | −.11** | — | ||||||||

| 7. Recent Indirect Terrorism Exposure | −.09** | .02 | .08** | −.02 | −.02 | .23** | — | |||||||

| 8. Benefit Finding | −.10** | .05 | .19** | −.13** | −.08* | .03 | .05 | — | ||||||

| 9. PTSD Total Symptoms | .05 | .16** | .12** | −.12** | −.19** | .16** | .06 | .33** | — | |||||

| 10. PTSD Reexperiencing Symptoms | .05 | .19** | .15** | −.11** | −.18** | .16** | .05 | .32** | .87** | — | ||||

| 11. PTSD Avoidance Symptoms | −.02 | .09** | .09** | −.10** | −.12** | .12** | .05 | .32** | .89** | .66** | — | |||

| 12. PTSD Hyperarousal Symptoms | .11** | .16** | .06 | −.11** | −.21** | .14** | .06 | .21** | .86** | .63** | .63** | — | ||

| 13. Exclusion of PCI | −.02 | .07* | .30** | −.13** | −.22** | .09** | −.01 | .19** | .22** | .23** | .17** | .18** | — | |

| 14. Threat Perception of PCI | −.00 | .05 | .24** | −.15** | −.25** | .09** | .01 | .17** | .21** | .21** | .16** | .20** | .67** | — |

Note. N = 961 using listwise deletion; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; PCI = Palestintian citizens of Israel.

p < .05;

p < .01 (all two-tailed significance).

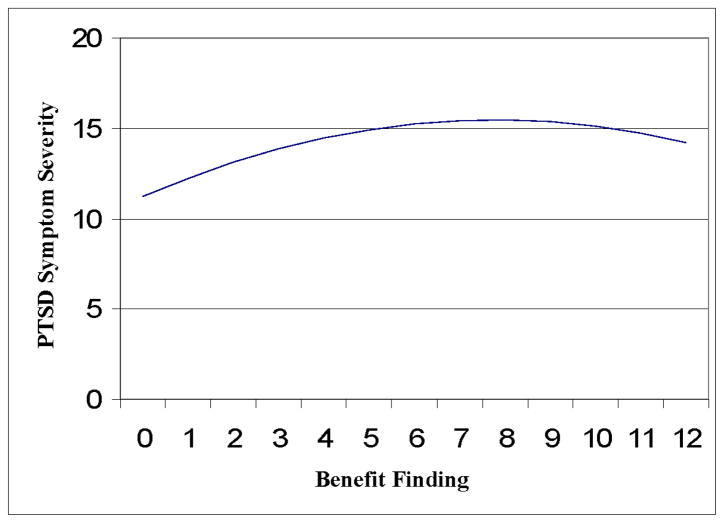

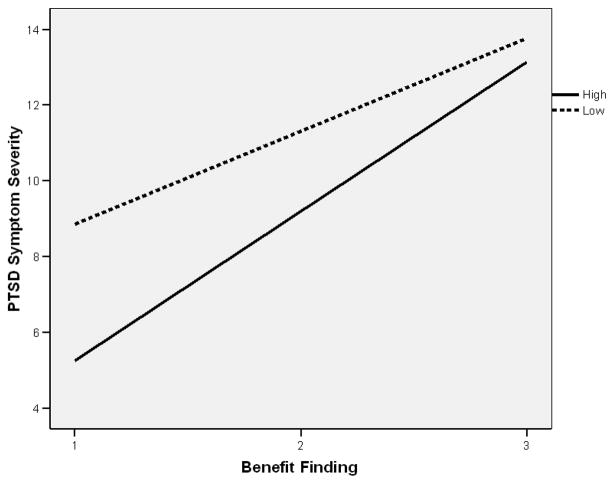

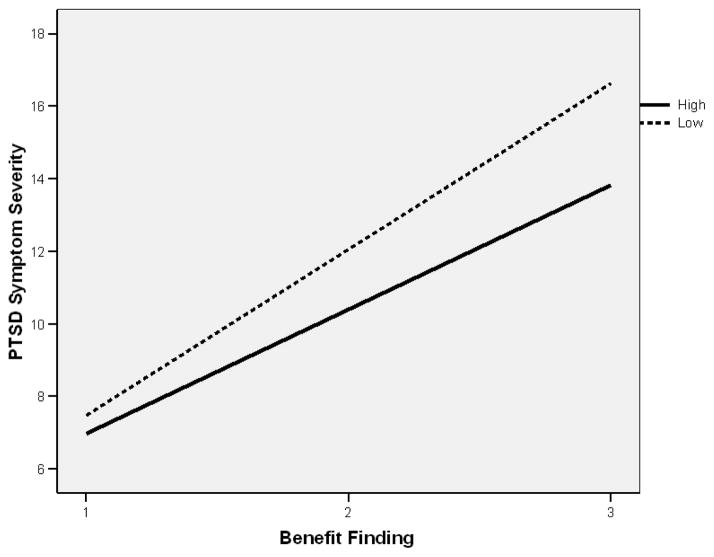

The results of the hierarchical linear regression are shown in Table 3. Being female, more religious, having lower educational and lower income levels were related to greater PTSD symptom severity on the first regression step. In the second step, experiencing direct terrorism exposure was related to greater PTSD symptom severity. In the next step, benefit finding significantly added to the model (change in model R2 was .10, p < .001), greater benefit finding being related to greater PTSD symptoms. An inverse relationship between benefit finding squared and PTSD symptom severity was found in the fourth step, indicating a significant curvilinear relationship between these constructs. The shape of the curvilinear relationship demonstrated that at low levels of benefit finding its relationship to PTSD symptom severity is stronger than at medium and high levels of benefit finding; the relationship between benefit finding and PTSD symptom severity reaches the peak of association at moderate levels of PTSD symptom severity (see Figure 1). On the fifth model step, a significant interaction between benefit finding and income, and benefit finding and education was observed. People with lower income reported greater PTSD symptom severity than people with higher income at lower levels of benefit finding. As benefit finding increased, these two groups became more similar to one another (see Figure 2). People with lower education reported greater PTSD symptom severity than people with higher education and this gap increased as reports of benefit finding increased. For both groups, as benefit finding increased so did reported PTSD symptom severity (see Figure 3). The final model step was not significant (p = .31).

TABLE 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis Summary for Variables Predicting PTSD Symptom Severity

| Variable | Step 1

|

Step 2

|

Step 3

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | β | sr2 | B | SEB | β | sr2 | B | SEB | β | sr2 | |

| Age | .03 | .02 | .04 | .03 | .02 | .05 | .04 | .02 | .07* | .004 | ||

| Sex (Female) | 2.98 | .58 | .15** | .022 | 2.82 | .58 | .14** | .020 | 2.61 | .54 | .13** | .020 |

| Religiosity | .98 | .42 | .07* | .004 | .92 | .42 | .07* | .004 | .20 | .40 | .01 | |

| Education | −1.11 | .32 | −.11** | .010 | −1.13 | .31 | −.11* | .011 | −.85 | .30 | −.08** | .010 |

| Income | −1.58 | .36 | −.13** | .020 | −1.44 | .36 | −.12** | .013 | −1.28 | .34 | −.11** | .010 |

| Direct Terrorism Exposure | 2.82 | .67 | .13** | .020 | 2.72 | .63 | .12** | |||||

| Indirect Terrorism Exposure | .80 | .58 | .04 | .51 | .55 | .03 | ||||||

| Benefit Finding | .88 | .07 | .33** | .010 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| R2 for model | .070 | .090 | .191 | |||||||||

| Adjusted R2 for model | .066 | .084 | .185 | |||||||||

| F statistic for Δ R2 | 16.96** | 11.69** | 139.70** | |||||||||

| Variable | Step 4

|

Step 5

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | β | sr2 | B | SEB | β | sr2 | |

| Age | .04 | .02 | .07* | .004 | .04 | .02 | .07* | .004 |

| Sex (Female) | .20 | .40 | .01** | .020 | 2.59 | .54 | .13** | .020 |

| Religiosity | −1.25 | .34 | −.10 | .10 | .40 | .01 | ||

| Education | .52 | .55 | .03** | .010 | −.89 | .29 | −.08** | .010 |

| Income | −.07 | .02 | −.12** | .010 | −1.27 | .34 | −.11** | .010 |

| Direct Terrorism Exposure | .04 | .02 | .07** | .010 | 2.75 | .63 | .12** | .010 |

| Indirect Terrorism Exposure | .20 | .40 | .01 | .52 | .55 | .03 | ||

| Benefit Finding | .52 | .55 | .03** | .090 | 1.09 | .10 | .40** | .090 |

| Benefit Finding2 | −.07 | .02 | −.12** | .010 | −.08 | .02 | −.12** | .010 |

| BF × Age | .01 | .01 | .04 | |||||

| BF × Sex | .04 | .15 | .01 | |||||

| BF × Religiosity | .19 | .11 | .05 | |||||

| BF × Education | −.17 | .08 | −.06* | .003 | ||||

| BF × Income | .24 | .09 | .07* | .010 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| R2 for model | .198 | .207 | ||||||

| Adjusted R2 for model | .191 | .197 | ||||||

| F statistic for Δ R2 | 9.92** | 2.58** | ||||||

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01. PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder. sr2 = Squared semi-partial correlation. BF = Benefit finding.

FIGURE 1.

The Curvilinear Relationship Between PTSD Symptom Severity and Benefit Finding.

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

FIGURE 2.

The interaction Between Benefit Finding and Participant Level of Income in the Prediction of PTSD Symptom Severity.

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. Low = below average income. High = above average income.

FIGURE 3.

The Interaction Between Benefit Finding and Participant Level of Education in the Prediction of PTSD Symptom Severity.

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. Low = low income. High = high income.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BENEFIT FINDING AND NEGATIVE OUTGROUP ATTITUDES

Table 2 presents the zero-order correlations between benefit finding and negative outgroup attitudes. Benefit finding was significantly and positively correlated with attitudes of threat perception of PCI and ethnic exclusionism of PCI.

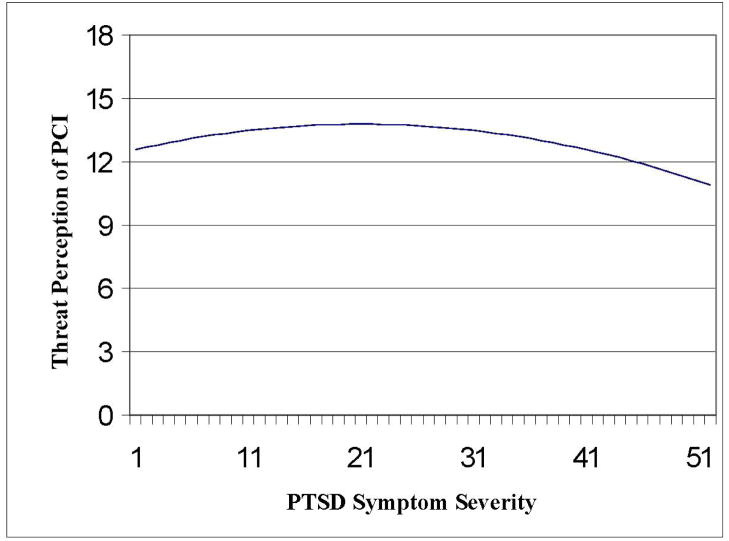

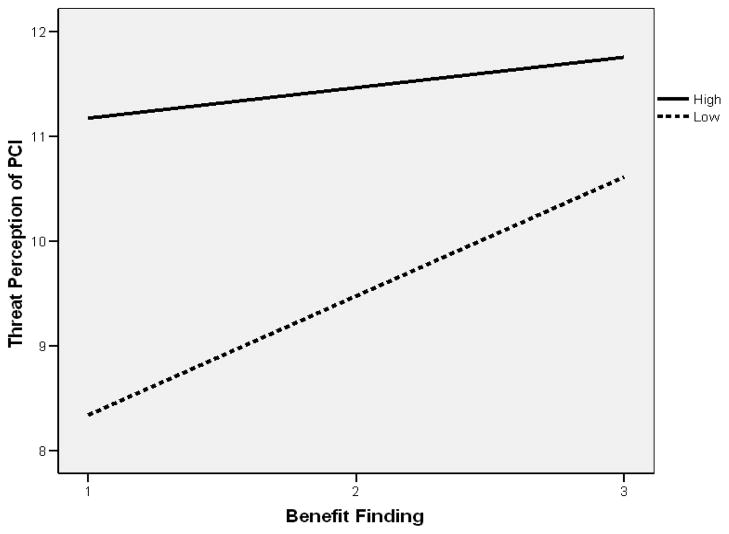

First we present the results for threat perception of PCI (see Table 4). Being more religious, having lower education and income levels were related to greater levels of threat perception of PCI on the first model step. In the second model step, direct terrorism exposure was related to greater threat perception of PCIs. In the next step, PTSD symptom severity was a positive and significant predictor. An inverse relationship between PTSD symptom severity squared and threat perception of PCI was found in the fourth step, indicating a significant curvilinear relationship between these constructs. The shape of the curvilinear relationship indicated that at moderate levels of PTSD symptom severity, endorsement of threat perception of PCI reached its peak. As severity continued to increase, the association between PTSD symptom severity and threat perception of PCI began to weaken (see Figure 4). In the fifth model step, benefit finding was positively and significantly related to threat perception of PCI. In the next step, the interaction between benefit finding and PTSD symptom severity was significant. This interaction indicated that for people who have high levels of PTSD symptom severity, benefit finding does not significantly affect their threat perception of PCI. However, for groups with lower levels of PTSD symptom severity, as benefit finding increased, so did their threat perception of PCI (see Figure 5). The final model step was not significant (p = .06).

TABLE 4.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis Summary for Variables Predicting Threat Perception of PCI

| Variable | Step 1

|

Step 2

|

Step 3

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | β | sr2 | B | SEB | β | sr2 | B | SEB | β | sr2 | |

| Age | −.01 | .01 | −.02 | −.01 | .01 | −.02 | −.01 | .01 | −.03 | |||

| Sex (Female) | .04 | .30 | .00 | .01 | .01 | −.02 | −.21 | .30 | −.02 | |||

| Religiosity | 1.45 | .22 | .20** | .040 | 1.46 | .22 | .20** | .040 | 1.38 | .22 | .19** | .030 |

| Education | −.53 | .16 | −.10** | .010 | −.53 | .16 | −.10** | .010 | −.44 | −.16 | .08** | .010 |

| Income | −1.24 | .19 | −.20** | .040 | −1.20 | .19 | −.19** | .030 | −1.08 | .19 | −.17** | .030 |

| Direct Terrorism Exposure | .76 | .35 | .07** | .004 | .52 | .35 | .04 | |||||

| Indirect Terrorism Exposure | −.26 | .30 | −.03 | −.31 | .30 | −.03 | ||||||

| PTSD Symptom Severity | .08 | .02 | .16** | .020 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| R2 for model | .110 | .114 | .136 | |||||||||

| Adjusted R2 for model | .106 | .108 | .130 | |||||||||

| F statistic for Δ R2 | 26.94** | 2.47** | 27.94** | |||||||||

| Variable | Step 4

|

Step 5

|

Step 6

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | β | sr2 | B | SEB | β | sr2 | B | SEB | β | sr2 | |

| Age | −.01 | .01 | −.03 | −.01 | .01 | −.02 | −.01 | .01 | −.00 | |||

| Sex (Female) | −.29 | .30 | −.03 | −.27 | .30 | −.03 | −.27 | .30 | −.03 | |||

| Religiosity | 1.35 | .22 | .18** | .030 | 1.27 | .22 | .17** | .030 | 1.29 | .22 | .18** | .030 |

| Education | −.43 | .16 | −.08** | .010 | −.41 | .16 | −.07** | .010 | −.43 | .16 | −.08** | .010 |

| Income | −1.07 | .19 | −.17** | .030 | −1.07 | .19 | −.17** | .030 | −1.04 | .19 | −.17** | .020 |

| Direct Terrorism Exposure | .45 | .35 | .04 | .48 | .35 | .04 | .47 | .34 | .04 | |||

| Indirect Terrorism Exposure | −.34 | .30 | −.03 | −.36 | −.30 | .03 | −.38 | .30 | −.04 | |||

| PTSD Symptom Severity | .12 | .02 | .23** | .030 | .10 | .02 | .19** | .020 | .01 | .02 | .19** | .020 |

| PTSD2 | −.00 | .00 | −.11** | .010 | −.00 | .00 | −.09** | .004 | −.00 | .00 | −.07 | |

| Benefit Finding | .11 | .04 | .08** | .010 | .13 | .04 | .09** | .010 | ||||

| BF × PTSD | −.01 | .00 | −.07* | .004 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| R2 for model | .142 | .147 | .151 | |||||||||

| Adjusted R2 for model | .135 | .140 | .142 | |||||||||

| F statistic for Δ R2 | 7.39** | 7.09** | 4.77** | |||||||||

Note.

p< .05.

p < .01. PCI = Palestinian citizen of Israel. sr2 = Squared semi-partial correlation. PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder. PTSD2 = posttraumatic stress disorder squared. BF = Benefit finding.

FIGURE 4.

The Curvilinear Relationship Between PTSD Symptom Severity and Threat Perception of PCI.

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. PCI=Palestinian Citizens of Israel.

FIGURE 5.

The Interaction Between Benefit Finding and PTSD Symptom Severity in the Prediction of Threat Perception of PCI.

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. PCI = Palestinian Citizen of Israel. Low = Below Average PTSD Symptom Severity; High = Above Average PTSD Symptom Severity.

Next, we present the results for ethnic exclusionism of PCI (see Table 5). Greater religiosity, lower education and lower income levels were related to greater ethnic exclusionism toward PCI on the first model step. Step two indicated that direct terrorism exposure was related to greater ethnic exclusionism of PCI. In the next step, greater PTSD symptom severity was related to greater ethnic exclusionism toward PCI. In the fourth model step, PTSD symptom severity squared was not significant (p = .44). In the fifth model step, benefit finding was positively and significantly related to greater ethnic exclusionism toward PCI. Model step six (p = .43) and seven (p = .16) were not significant.

TABLE 5.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis Summary for Variables Predicting Ethnic Exclusionism of PCI

| Variable | Step 1

|

Step 2

|

Step 3

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | β | sr2 | B | SEB | β | sr2 | B | SEB | β | sr2 | |

| Age | −.01 | .01 | −.03 | −.01 | .01 | −.03 | −.02 | .01 | −.04 | |||

| Sex (Female) | .43 | .34 | .04 | .39 | .34 | .03 | .12 | .34 | .01 | |||

| Religiosity | 2.04 | .25 | .24* | .060 | 2.06 | .25 | .24** | .060 | 1.97 | .25 | .23** | .050 |

| Education | −.55 | .18 | −.09** | .010 | −.56 | .18 | −.09** | .010 | −.45 | .18 | .07* | .010 |

| Income | −1.17 | .21 | −.16** | .030 | −1.12 | .21 | −.16** | .020 | −.99 | .21 | −.14** | .020 |

| Direct Terrorism Exposure | .92 | .39 | .07* | .004 | .67 | .39 | .05 | |||||

| Indirect Terrorism Exposure | −.59 | .34 | −.05 | −.67 | .34 | −.06* | .003 | |||||

| PTSD Symptom Severity | .09 | .02 | .16** | .020 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| R2 for model | .119 | .124 | .146 | |||||||||

| Adjusted R2 for model | .115 | .119 | .140 | |||||||||

| F statistic for Δ R2 | 29.43** | 3.55** | 28.45** | |||||||||

| Variable | Step 4

|

Step 5

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SEB | β | sr2 | B | SEB | β | sr2 | |

| Age | −.02 | .01 | −.04 | −.01 | .01 | −.04 | ||

| Sex (Female) | .09 | .34 | .01 | .12 | .34 | .01 | ||

| Religiosity | 1.96 | .25 | .23** | .050 | 1.85 | .25 | .22** | .040 |

| Education | −.45 | .18 | −.07* | .010 | −.43 | .18 | −.07* | .004 |

| Income | −.99 | .21 | −.14** | .020 | −.99 | .21 | −.14** | .020 |

| Direct Terrorism Exposure | .67 | .39 | .05 | .64 | .39 | .05 | ||

| Indirect Terrorism Exposure | −.67 | .34 | −.06* | .003 | −.67 | .34 | −.06* | .003 |

| PTSD Symptom Severity | .09 | .02 | .16** | .020 | .11 | .02 | .18** | .020 |

| PTSD Symptom Severity2 | .00 | .00 | −.03 | .00 | .00 | −.02 | ||

| Benefit Finding | .14 | .05 | .09** | .010 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| R2 for model | .147 | .154 | ||||||

| Adjusted R2 for model | .140 | .146 | ||||||

| F statistic for Δ R2 | .59 | 8.42** | ||||||

Note.

p< .05.

p < .01. PCI = Palestinian citizen of Israel. sr2 = Squared semi-partial correlation. PTSD = Posttraumatic stress disorder. PTSD2 = posttraumatic stress disorder squared.

DISCUSSION

We examined the relationship between benefit finding, PTSD symptom severity, and negative outgroup attitudes in Israel during a period of widespread and ongoing terrorism. We particularly examined in what manner benefit finding was related to psychological distress by testing recent meta-analytic findings within this terrorism context. We also examined the potential for benefit finding to relate to negative outgroup attitudes by integrating benefit finding into the theoretical framework offered by prevailing theories of in-group and outgroup processes.

Benefit finding was related to greater PTSD symptom severity. This finding is consistent with recent literature (Butler et al., 2005; Hobfoll, Canetti-Nisim, et al., 2006; Laufer & Solomon, 2006) and adds to the growing number of studies suggesting that benefit finding and psychopathology are positively related to one another within terrorism contexts. Consistent with previous research (Butler et al., 2005), we found a curvilinear relationship between benefit finding and PTSD symptom severity. Benefit finding was related to PTSD symptom severity at moderate levels of severity, but this relationship waned as severity increased. Although benefit finding and PTSD are related, benefit finding is not related to the most severe distress that people in this study reported.

We did not find differences in the relationship between benefit finding and PTSD with regard to age, sex, religiosity, and trauma exposure as was previously reported (Helgeson et al., 2006), indicating that benefit finding is related to PTSD irrespective of these potential moderators in this study. We did find two significant interaction effects such that level of income and level of education moderated the relationship between benefit finding and PTSD symptom severity. The interaction suggested that income and education functioned as protective factors against distress, and as benefit finding increased, the ability of income and education level to protect against distress diminished.

To our knowledge this is the first study that tested these moderating factors within the context of ongoing terrorism.

The theorized link between benefit finding and negative outgroup attitudes was supported by the study findings. Benefit finding was positively related to greater negative outgroup attitudes such that people with higher levels of benefit finding endorsed greater perceived threat of PCI and greater exclusionism of PCI. This relationship was consistently demonstrated, controlling for the effect of demographic variables and PTSD symptom severity. An interaction between benefit finding and PTSD symptom severity was observed in the model predicting threat perception of PCI. People who had higher levels of PTSD symptom distress reported rather consistent and high levels of threat perception across levels of benefit finding. However, as benefit finding increased, those who reported lower PTSD symptom severity increased in their threat perception of PCI. People with higher levels of PTSD symptoms may be endorsing higher threat perception of PCI as a trauma-related reaction, or may be experiencing greater stereotyping of PCI as a threatening out-group (Schimel et al., 1999). For those with fewer symptoms, benefit finding may be indicative of enhanced group cohesion under adverse conditions and could therefore lead to greater outgroup threat perception (Castano & Dechesne, 2005; Jackson, 1993; Moskalenko et al., 2006). The association between benefit finding and negative outgroup attitudes may suggest that it is a defensive form of coping in the face of ongoing terrorism, but given its association with PTSD symptom severity, benefit finding may not be able to countermand the negative psychological toll of terrorism exposure. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report associations between benefit finding and negative outgroup attitudes.

It is important to note that results of the current investigation should be interpreted within the context of ongoing and continuous events of terrorism. The participants in this study reported benefit finding in response to terrorism exposure occurring during the second Intifada, and because this epoch was marked with significant and widespread terror attacks, benefit finding in this context may be different than growth reported following single-incident trauma exposure.

It may be possible that if we were to ask participants after the end of the Intifada to report on their benefit finding experiences, a different picture could emerge. As Tedeschi and Calhoun have suggested, it may indeed take time for growth to occur, and early assessment of benefit finding may be indicative of active coping processes rather than stable and positive life changes (Tedeshi & Calhoun, 2004). Furthermore, the population also faced uncertainty whether terror attacks would continue and this may also have influenced the benefit finding reported in this sample. As Helgeson and colleagues noted (2006) the literature on benefit finding contains within it a variety of different approaches and interpretations. In the current study, benefit finding may be more related to coping processes as the assessment of benefit finding occurs during ongoing exposure to terrorism.

It appears that within the political context of Israel and the experience of repeated acts of terrorism, participants endorsed benefit finding and thereby endorsed greater interpersonal affiliation (e.g., changes in the closeness with others), feelings of strength, and enhanced life purpose. However, negative outcomes of perceived threat and exclusionism were related to these perceived benefits. Although this form of defense may serve vital coping functions in the face of terror (Hobfoll, Canetti-Nisim, et al., 2006), especially to protect against the loss of social status and cultural identity (Pedhazur & Yishai, 1999), it may also have the negative result of further destabilizing already poor PCI-Jewish relations, and continue cycles of xenophobic reactions toward PCI (Pedhauzer & Yishai, 1999).

Referring to terror management theory (Greenberg et al., 1986), one form of defending oneself from threat is finding closeness with others who share one’s worldview, fears, and national identity. Negative outgroup attitudes may be an unintended consequence of the type of meaning making people engage in when threatened with terror (Greenberg, Schimel, Martens, Solomon, & Pyszcznyski, 2001; McGregor et al., 1998). Although this study cannot rule out the possibility that mortality salience could increase positive, or prosocial attitudes among some participants (Niesta, Fritsche, & Jonas, 2008), the threat from terrorism to Israel and to the ideological purpose of living in this land may be so great that it overwhelms the attitudes of benevolence and justice that certainly occur as values within the Israeli population as well.

Results from this study offer preliminary evidence suggesting that PTSD symptom severity can attenuate the degree to which individuals respond to outgroups as threatening. We interpret the curvilinear relationship between PTSD symptom severity and threat perception of PCI to indicate that when PTSD symptoms reach a certain threshold, the defensive processes predicted by terror management theory are overwhelmed.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, being cross-sectional in its design, causal order cannot be delineated. Studies utilizing prospective designs are warranted to elaborate on the causal mechanisms relating to benefit finding and psychopathology, especially as benefit finding has been shown to be salutogenic when it stably occurs over time (Frazier et al., 2001; McMillen et al., 1997). Another limitation is that we did not measure the participants’ subjective report of the severity of their traumatic event exposure, but instead examined whether participants experienced direct or indirect exposure to terrorism. It may be entirely possible that variation exists in the degree to which terrorism exposure is felt by our participants as traumatic. In addition, the large-scale nature of this project did not allow for inclusion of longer scales to evaluate the constructs under investigation. As a result, we could not utilize one of the commonly used measures of benefit finding in this study (e.g., the PTGI). In our effort to represent benefit finding as it has been commonly done in the literature, our measure does contain similar items as the Tedeschi and Calhoun scale (1996). Another limitation was that we were not able to assess for significant other or peer ratings of benefit finding in order to corroborate participants’ self-reported benefit finding. In addition, although the benefit finding construct is related to ingroup cohesion, it is not a perfect exemplar of this construct. It is instead a measure of affiliation with others that are ostensibly like oneself (family/friends), and it would be predicted based on group dynamics, that affiliation in this context could very well be directed toward ingroup members.

Certain strengths of the study are also noteworthy. Being a large scale national sample, generalizability across ethnic subgroups, age, sex, and socioeconomic levels is also possible. It is also one of the first theory-based studies of terrorism’s impact (see also Hobfoll, Canetti-Nisim, et al., 2006; Silver et al., 2002), and as such may contribute to a better understanding of terrorism—most studies being epidemiological in nature. Further, many studies have examined benefit finding in health contexts which is qualitatively different than addressing benefit finding in relation to confrontation with a trauma such as terrorism. By studying a very different threat context, we potentially broaden the understanding of benefit finding which is clearly complex.

It is necessary for further research to focus on benefit finding within a longitudinal framework to determine if outcomes, whether they are positive or negative, are stable over time. Additional work in the area of benefit finding following terrorism is warranted to improve our understanding of the mechanisms related to positive changes reported in this context. Furthermore, studies need to address benefit finding as a possible mechanism that facilitates or attenuates adaptation to trauma, not simply as a positive reaction to trauma, or an outcome unrelated to psychological functioning. Continued work assessing benefit finding as it may relate to negative outgroup attitudes is also necessary to further understand this relationship.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by a grant from the National Institute of Health, grant number 5R01MH73687-3, “Terrorism and Traumatic Responding: Exposure and Resiliency Factors.”

We would like to thank anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and comments. We would also like to thank Joel Hughes, Ph.D., for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

We conducted separately an analysis of only those participants to reported experiencing direct exposure to terrorism. The results of this analysis were the same in terms of analytic outcome and interpretability.

Contributor Information

BRIAN J. HALL, Kent State University and Rush University Medical Center

STEVAN E. HOBFOLL, Rush University Medical Center

DAPHNA CANETTI, Yale University and University of Haifa.

ROBERT J. JOHNSON, University of Miami

SANDRO GALEA, University of Michigan.

References

- Ai AL, Cascio T, Santangelo LK, Evans-Campbell T. Hope, meaning, and growth following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:523–548. doi: 10.1177/0886260504272896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, West S. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Becker E. The denial of death. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bleich A, Gelkopf M, Solomon Z. Exposure to terrorism, stress-related mental health symptoms, and coping behaviors among a nationally representative sample in Israel. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:612–620. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler LD, Blasey CM, Garlan RW, McCaslin SE, Azarow J, Chen XH, et al. Posttraumatic growth following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001: Cognitive, coping, and trauma symptom predictors in an internet convenience sample. Traumatology. 2005;11:247–267. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT. Ethnocentric and other altruistic motives. In: Levine D, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation 1965. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1965. pp. 283–312. [Google Scholar]

- Castano E, Dechesne M. On defeating death: Group reification and social identification as immortality strategies. European Review of Social Psychology. 2005;16:221–255. [Google Scholar]

- Castano E, Yzerbyt V, Paladino MP, Sacchi S. I belong, therefore, I exist: Ingroup identification, ingroup entitativity, and ingroup bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Elder G, Clipp E. Combat experience, comradeship, and psychological health. In: Wilson JP, Harel Z, Kahanna B, editors. Human adaptation to extreme stress. New York: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer P, Greitemeyer T, Kastenmüller A, Frey D, Oßwald S. Terror salience and punishment: Does terror salience induce threat to social order? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2007;43:964–971. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Conlon A, Glaser T. Positive and negative life changes following sexual assault. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:1048–1055. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Bucuvalas M, Gold J, et al. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa013404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J, Arndt J, Schimel J, Pyszczynski T, Solomon S. Clarifying the function of mortality salience-induced worldview defense: Renewed suppression or reduced accessibility of death-related thoughts? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2001;37:70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T, Solomon S. The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In: Baumeister RF, editor. Public and private self. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986. pp. 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J, Schimel J, Martens A, Solomon S, Pysczcynski T. Sympathy for the devil: Evidence that reminding whites of their mortality promotes more favorable reactions to white racists. Journal of Motivation and Emotion. 2001;25:113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Grieve PG, Hogg MA. Subjective uncertainty and intergroup discrimination in the minimal group situation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:926–940. [Google Scholar]

- Hall BJ, Hobfoll SE, Palmieri P, Canetti–Nisim D, Shapira O, Johnson RJ, Galea S. The psychological impact of impending forced settler disengagement in Gaza: Trauma and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:1–10. doi: 10.1002/jts.20301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BJ, Hobfoll SE. Unpublished Data. Kent State University; 2008. The nature and meaning of posttraumatic growth measures. [Google Scholar]

- Halloran MJ, Kashima ES. Social identity and worldview validation: The effects of ingroup identity primes and mortality salience on value endorsement. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30(7):915–925. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA, Tomich PL. A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:797–816. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberger G. Terror management and attributions of blame to innocent victims: Reconciling compassionate and defensive responses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:832–844. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberger G, Ein-Dor T. Defenders of a lost cause: Terror management and violent resistance to the disengagement plan. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:761–769. doi: 10.1177/0146167206286628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Lilly RS. Resource conservation as a strategy for community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:128–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Canetti-Nisim D, Johnson R. Exposure to terrorism, stress-related mental health symptoms, and defensive coping among Jews and Ar-abs in Israel. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:207–218. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Tracy M, Galea S. The impact of resource loss and “traumatic growth” on probable PTSD and depression following terrorist attacks. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:867–878. doi: 10.1002/jts.20166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huddy L, Khatid N, Capelos T. Trends: Reactions to the terrorism attacks of September 11, 2001. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2002;66:418–450. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby J. Speaking out against terror. The Boston Globe; 2001. Sep 23, p. D7. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JW. Realistic group conflict theory: A review and evaluation of the theoretical and empirical literature. The Psychological Record. 1993;43:395–414. [Google Scholar]

- Jetten J, Hogg MA, Mullin BA. In-group variability and motivation to reduce subjective uncertainty. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2000;4:184–198. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman HC. The interdependence of Israeli and Palestinian national identities: The role of the other in existential conflicts. Journal of Social Issues. 1999;55:581–600. [Google Scholar]

- Laufer A, Solomon Z. Posttraumatic symptoms and posttraumatic growth among Israeli youth exposed to terror incidents. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:429–448. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman DR, Davis CG, DeLongis A, Wortman CB, Bluck S, Mandel D, et al. Positive and negative life changes following bereavement and their relations to adjustment. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 1993;12:90–112. [Google Scholar]

- Linley PA, Joseph S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:11–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor HA, Lieberman JD, Greenberg J, Solomon S, Arndt J, Simon L, Pyszczynski T. Terror management and aggression: Evidence that mortality salience motivates aggression against worldview-threatening others. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1998;74:590–605. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen JC, Smith EM, Fisher RH. Perceived benefit and mental health after three types of disaster. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:733–739. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Florian V, Hirschberger G. The existential function of close relationships: Introducing death into the science of love. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2003;7:20–40. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0701_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskalenko S, McCauley C, Rozin P. Group identification under conditions of threat: College students’ attachment to country, family, ethnicity, religion, and university before and after September 11, 2001. Political Psychology. 2006;27:77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mullin BA, Hogg MA. Dimensions of subjective uncertainty in social identification and minimal intergroup discrimination. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1998;37:345–365. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1998.tb01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Security Studies Center Terrorism Database. Terrorism research: The terrorism project. 2005 Retrieved April 9, 2006 from http://nssc.haifa.ac.il/Terror/index.html.

- Niesta D, Fritsche I, Jonas E. Mortality salience and its effects on peace processes: A review. Social Psychology. 2008;39:48–58. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary VE, Ickovics JR. Resilience and thriving in response to challenge: An opportunity for a paradigm shift in women’s health. Women’s Health: Research on Gender, Behavior, and Policy. 1995;1:121–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paez D, Basabe N, Ubillos S, Gonzalaz-Castro J. Social sharing, participation in demonstrations, emotional climate, and coping with collective violence after the March 11th Madrid bombings. Journal of Social Issues. 2007;63:323–337. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Cohen LH, Murch RL. Assessment and prediction of stress-related growth. Journal of Personality. 1996;64:71–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedhazur A, Yishai Y. Hatred by hated people: Xenophobia in Israel. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 1999;22:101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski T, Solomon S, Greenberg J. In the wake of 9/11: The psychology of terror. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski T, Abdollahi A, Solomon S, Greenberg J, Cohen F, Weise D. Mortality salience, martyrdom, and military might: The great Satan versus the axis of evil. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:525–537. doi: 10.1177/0146167205282157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt A, Greenberg J, Solomon S, Pyszczynski T, Lyon D. Evidence for terror management theory: I. The effects of mortality salience on reactions to those who violate or uphold cultural values. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1989;57:681–690. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.4.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheepers P, Gijsberts M, Coenders M. Ethnic exclusionism in European countries: Public opposition to civil rights for legal migrants as a response to perceived ethnic threat. European Sociological Review. 2002;18:17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schimel J, Simon L, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T, Solomon S, Waxmonsky J, et al. Stereotypes and terror management: Evidence that mortality salience enhances stereotypic thinking and preferences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:905–926. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenger WE, Caddell JM, Ebert L, Jordan BK, Rourke KM, Wilson D, et al. Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: Findings from the national study of Americans’ reactions to September 11. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:581–588. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Collins RL, Marshall GN, Elliott MN, et al. A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:1507–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200111153452024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamir M, Sullivan J. Jews and Arabs in Israel: Everybody hates somebody sometimes. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 1985;29:283–305. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif M. Group conflict and co-operation: Their social psychology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Silver RC, Holman EA, McIntosh DN, Poulin M, Gil-Rivas V. Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:1235–1244. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.10.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon L, Arndt J, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T, Solomon S. Terror management and meaning: Evidence that the opportunity to defend the world-view in response to mortality salience increases the meaningfulness of life in the mildly depressed. Journal of Personality. 1998;66:359–382. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon S, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T. The cultural animal: Twenty years of terror management theory and research. In: Greenberg J, Koole S, Pyszczynski T, editors. The handbook of experimental existential psychology. New York: The Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stein AA. Conflict and cohesion: A review of the literature. The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 1976;20:143–172. [Google Scholar]

- Stuber J, Galea S, Boscarino JA, Schlesinger M. Was there unmet mental health need after September 11th, 2001 terrorist attacks? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41:230–240. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Billig MG, Bundy RP, Flament C. Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1971;1:149–178. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Trauma and transformation: Growing in the aftermath of suffering. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:455–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02103658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The foundations of posttraumatic growth: New considerations. Psychological Inquiry. 2004;15:93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Tomich PL, Helgeson VS. Is finding something good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among women with breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2004;23:16–23. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Val EB, Linley PA. Posttraumatic growth, positive changes, and negative changes in Madrid residents following the March 11, 2004, Madrid train bombings. Journal of Loss & Trauma. 2006;11:409–424. [Google Scholar]

- Wild ND, Paivio SC. Psychological adjustment, coping, and emotion regulation as predictors of posttraumatic growth. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2003;8:97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Wisman A, Koole SL. Hiding in the crowd: Can mortality salience promote affiliation with others who oppose one’s worldviews? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:511–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoellner T, Maercker A. Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology: A critical review and introduction of a two component model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:626–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]