Abstract

The intersection of particles and directed energy is a rich source of novel and useful technology that is only recently being realized for medicine. One of the most promising applications is directed drug delivery. This review focuses on phase-shift nanoparticles (that is, particles of submicron size) as well as micron-scale particles whose action depends on an external-energy triggered, first-order phase shift from a liquid to gas state of either the particle itself or of the surrounding medium. These particles have tremendous potential for actively disrupting their environment for altering transport properties and unloading drugs. This review covers in detail ultrasound and laser-activated phase-shift nano- and micro-particles and their use in drug delivery. Phase-shift based drug-delivery mechanisms and competing technologies are discussed.

During the last decade, advances in nano-medicine have allowed the combining of various functionalities in molecular or supramolecular constructs, that is, nanoparticles. The family of nanoparticles includes polymeric micelles, liposomes, hollow particles and nano- or micro-emulsion droplets, as well as metallic nanospheres, rods, shells and cages, and carbon-based nanotubes and balls. Micron and submicron sized particles are also being constructed using top-down (lithography) rather than bottom-up (self-assembly) processes in porous silica, hydrogels and polymers. Various chemotherapeutic drugs, imaging agents and targeting moieties may be encapsulated in the same nanocontainer. The ability to combine chemotherapeutic agents and imaging agents may provide for early assessment of response to treatment and allow personalized therapy [1–5].

Tumor tissue is characterized by poor vascularization, poorly organized vascular architecture, irregular blood flow and reduced lymphatic drainage. Leaky blood vessels and the lack of a lymphatic system result in an increased interstitial fluid pressure, which hinders convectional transport of drug carriers across blood vessel walls. Nevertheless, nanoparticles of appropriate size may accumulate in tumor tissue via the enhanced permeability and retention effect [6] based on defective tumor microvasculature. A characteristic pore cutoff size range between 380 and 780 nm has been shown in a variety of tumors, although in some tumors the size may increase up to 2 μm. This allows extravasation of drug-loaded nanoparticles through large interendothelial gaps [6–8], while the poor lymphatic drainage of tumors results in longer retention of extravasated particles in tumor tissue. In contrast to tumors, blood vessels in normal tissues have tight inter-endothelial junctions (characteristic cutoff size of 7.5 nm), which do not allow extravasation of nanoparticles.

Effective tumor accumulation of nano-particles via the enhanced permeability and retention effect requires sufficient particle residence time in circulation. To provide for this, nanoparticles are commonly coated with poly(ethylene oxide) (PEG) chains that decrease blood protein adsorption and particle recognition by the cells of the reticulo-endothelial system. The efficiency of this approach depends on a number of factors, such as the degree of surface coating, PEG chain length and motion, and nanoparticle size [9,10]. This important problem has not yet been studied in detail.

Drug encapsulation in nanocarriers may dramatically increase the effective aqueous solubility of highly potent drugs whose application has been hampered by low solubility. Encapsulation also prevents drug degradation while in circulation, reduces side effects, and allows drug transport towards desired targets. However, for effective therapeutic action, drugs should be released from carriers at the site of action. This can be provided by developing stimuli-responsive drug carriers. After tumor accumulation, local release of the encapsulated drug in tumor tissue may be triggered by various internal (i.e., pH, hypoxia and enzymatic degradation) or external physical stimuli, for example, ultrasound or light (for recent reviews see [11,12]). The state-of-the-art in the application of ultrasound and light for targeted drug delivery is discussed below, with special emphasis on the role of triggered phase-shift transition inside or in the vicinity of injected nanoparticles.

Targeted drug-delivery mechanisms

Thermal effects

Localized heating of tissues has been produced by various external stimuli, including ultrasound at various frequencies or electromagnetic (EM) fields (radio frequency, microwave and laser light). In general, the heat produced depends on the tissue absorption of the energy and the rates of thermal diffusion and convection. For both ultrasound and EM fields, absorption is frequency dependent. Ultrasound absorption increases monotonically with frequency, while EM has a more complex frequency dependence since, particularly in the microwave range and above, various molecules may each exhibit their own absorption spectrum. Note that even a moderate temperature increase may significantly increase permeability of blood capillaries [13–15]. On the cellular level, temperature increase may lead to cell membrane fluidization [16,17]. This effect may be accompanied by mechanical permeabilization (poration) of cell membranes (see below). Laser and external alternating electric (MHz frequency range acting on conducting nanoparticles) and magnetic (kHz frequency acting on ferromagnetic nanoparticles) fields are being studied in combination with energy-absorbing nanoparticles for local hyperthermia treatments that could potentially be useful in drug delivery [18–23].

Temperature-sensitive liposomes have been developed that rapidly release their contents at physiologically tolerated tissue temperatures [24–26]. Heating produces a gel-to-fluid phase transition in the phospholipid membrane that enhances diffusion and releases the drug in the target region. These nanoparticles, loaded with the chemotherapeutic doxorubicin (DOX) have been commercialized (ThermoDox®, Celsion Corp.), and are undergoing clinical trials in combination with radio frequency thermal ablation [27,28]. Ultrasound as a heating modality is also being studied for release of drugs from these and similar low temperature-sensitive liposomes [29–33]. In fact, liposomes remain the most broadly investigated ultrasound-responsive drug-delivery vehicles.

Harnessing laser heating of plasmonic nanoparticles for drug release is also a goal for many groups [34]. Most of these rely on the low level heat produced by continuous laser sources to induce increased diffusion and release from various drug carriers, including the nanoparticles themselves, thin polymer shells, liposomes, hydrogels and nanocages [35–53].

Mechanical action by cavitation

Mechanical action by cavitation on the target tissue and drug carriers has been studied extensively only in the case of ultrasound. This action can be substantially enhanced by the introduction of gas-filled microbubbles. In current clinical practice, microbubbles have been used as ultrasound contrast agents for cardiovascular imaging [54,55] and for molecular imaging [56]. During the last decade, microbubbles have attracted attention as drug carriers and enhancers of drug and gene delivery. Several research groups have concentrated their efforts on developing microbubble-based drug-delivery systems [57–82].

In the ultrasound field, microbubbles grow by rectified diffusion and collapse in a process called inertial cavitation (IC). IC of microbubbles creates microjets and shock waves that can create holes in blood vessels and cell membranes, thus increasing their permeability for drugs, genes and their carriers. The ultrasound-induced creation of pores in cell membranes is called sonoporation [29,83–94]. Although the mechanisms are very different, the end result of sonoporation is similar to the more common electroporation method. However, sonoporation is considered a safer alternative for in vivo delivery. Laser-based ‘photoporation’ is also possible [95–98].

Inertial cavitation of systemically injected microbubbles can induce alternating invagination and distention of blood vessel walls, which can cause damage of the endothelial lining and temporarily increase vessel permeability [99–102]. For blood vessels that are large in comparison to microbubble sizes, invagination appears to be a major vessel damaging factor; for small blood capillaries, both invagination and distension result in endothelial damage and increased permeability [100]. At ultrasound energies that do not induce IC, microbubbles stably oscillate in the ultrasound field. This process is called stable cavitation.

Cavitation modes of ultrasound have also been used for opening liposomal membranes [103–105]. The development of ultrasound-responsive stable liposomes that manifest prolonged circulation time and effective tumor targeting has been recently reported [106–108]. Also important is the potential for ultrasound to affect the intracellular drug distribution by overcoming the barrier created by the nuclear membrane [109].

The most cost-effective way to develop micro-bubble-based drug-delivery systems would be to impart drug carrier properties to US FDA-approved ultrasound contrast agents, such as Optison™ (Amersham Inc.) or Definity® (Lanteus Medical Imaging Inc.). This approach may be very beneficial for drug delivery and targeting to intravascular targets [104,105,110–123]. The unexpected therapeutic action of micro-bubbles and low duty cycle ultrasound on subcutaneously grown glioma xenografts was recently reported [124]. Signals from molecularly targeted adherent agents can be obscured by echoes from tissue and freely circulating microbubbles. Methods have been suggested to distinguish between molecularly targeted and freely floating microbubbles or tissue [125–127].

Despite their success in hitting intravascular targets, the currently used contrast agents present a number of inherent problems as tumor-targeted drug carriers. The ideal ultrasound-mediated tumor-targeted drug carrier should satisfy a number of requirements: stability in circulation; drug retention until activated; size that allows extravasation through defective tumor vasculature; and ultrasound responsiveness. The very short circulation time (minutes) of commercially available microbubbles and their relatively large size (2–10 microns) do not allow effective extravasation into tumor tissue, thus preventing effective drug targeting. Only a fraction of the drug ultrasonically released from microbubbles into circulation is expected to reach tumor tissue while other fraction will circulate with blood flow and eventually reach unwanted off-target sites. This problem may be solved by developing phase-shift nanodroplets that convert into microbubbles under the action of ultrasound or laser irradiation. The strong interaction between the drug and the droplet-stabilizing shell prevents the premature release of the drug from nanodroplets despite their high surface area. This problem is discussed in the ‘Physical stimuli responsive carrier’ section.

Mechanical action in the absence of cavitation

Mechanical action in the absence of cavitation may also have consequences for drug transport in tissues. Although some have contemplated the possible action of the high dynamic pressures in the ultrasound wave itself [128], the most frequently discussed nonthermal and noncavitation mechanisms are related to acoustic streaming and ultrasound radiation forces. Sound propagating through a medium produces a force upon the medium itself, resulting in translation of the fluid, termed acoustic streaming, and also on particles suspended in the medium, termed the radiation force [59,60]. Acoustic streaming and the radiation force each produce particle translation in the acoustic field and their effects can be combined. Although radiation forces can easily deflect gas-filled particles even with low time-averaged acoustic intensity [59], a greater average intensity is needed to deflect liquid and solid particles. It has been demonstrated that acoustic streaming and/or radiation force presents a means to localize and concentrate droplets and bubbles near a vessel wall, which may assist the delivery of targeted agents. The application of radiation force pulses can bring the delivery vehicle into proximity with the cell for successful adhesion of the vehicle or its fragments to cell membranes [129]. Actively targeted acoustically active lipospheres were used to deliver paclitaxel (PTX) to primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells overexpressing ανβ3 integrins [130]. Circulating particles were deflected by radiation force to a vessel wall and could subsequently be fragmented by stronger pulses. Drug delivery was limited to the focal area of ultrasound [59].

The frequency dependence of particle velocity is different for acoustic streaming and radiation force, which allowed for the discrimination of the role of each factor in translation of perfluorocarbon (PFC) nanodroplets in the ultrasound field [60]. In that study by Dayton et al., PFC nanoparticles containing a core of at least 50% liquid PFCs (90% per-fluorohexane [PFH] and 10% perfluoropentane [PFP]) and a mixture of triacetin and soybean oils were used. These droplets were stabilized by a lipid membrane. Nearly all nanodroplets suspended in the solution were observed to translate at approximately the same velocity. Theory and experiments demonstrated the displacement of PFC nanoparticles in the direction of ultrasound (US) propagation. A traveling US wave with a peak pressure on the order of megapascals and frequency in the megahertz range produced a translational velocity that was proportional to acoustic intensity and increased with increasing center frequency. Experimental results obtained in this paper led its authors to conclude that acoustic streaming dominated in large blood vessels (with a magnitude of hundreds of micrometers per second for particle displacement). Radiation force on the particles themselves was also present and was expected to dominate in the microvasculature because acoustic streaming drops with decreasing vessel diameter.

In addition, acoustic radiation forces may create sheer stresses that increase inter-endothelial gaps and extracellular space, resulting in increased extravasation and diffusion of drug carriers and drugs in sonicated tissues [131–137]. The mismatch between acoustic impedances of water or tissue (1.4 MRayl) and PFC (approximately 0.3 MRayl) may promote generation of sheer stresses in the presence of microbubbles. Acoustic streaming and radiation force can also push nanoparticles through blood capillary walls thus enhancing extravasation of drug carriers or macromolecular drugs [59,60,62,138,139]. In an interesting new application, the ultrasound radiation force was used to modulate ligand exposure on the surface of targeted contrast agents [140]. Under the action of the radiation force, the adhesive properties of the contrast agent surface were changed from stealth to sticky when a ligand that had been hidden in the droplet shell became exposed to the cell receptor under the action of ultrasound.

Ultimately, the thermal and mechanical action of ultrasound on drug carriers and biological tissues enhances perfusion, increases extravasation of drugs and/or carriers, and enhances drug diffusion throughout tumor tissue, facilitating drug penetration through the various biological barriers. The increased intracellular uptake of nanoparticles, genes and drugs results in significantly enhanced therapeutic efficacy over conventional drugs [68,141–145].

Physicochemical mechanisms

Physicochemical mechanisms may also provide ways of controlling drug delivery. In particular, photodynamic therapy has had some clinical success. The technique relies on the local (laser) photo-excitation of particular molecules, mainly porphyrins, which release a cascade of cytotoxic reactive oxygens and free radicals for tumor-cell killing [146–148]. The technique is generally limited by the depth of light penetration to superficial tumors of the skin, GI tract or eye. Similar molecules have been used in conjunction with ultrasound purportedly to induce a similar effect [149,150], although sorting out the precise mechanism is complicated by the need for cavitation to make it work. In the case of ultrasound, it is the action of the collapsing microbubbles that enhances the production of free radicals [151].

Physical stimulus-responsive phase-shift drug carriers

Ultrasound-triggered drug delivery

Among various imaging and therapeutic modalities, ultrasound is the most cost effective, safe (e.g., in contrast to x-ray computed tomography (CT) or PET) and accessible. In addition, ultrasound can provide real-time feedback. Ultrasound imaging may be combined with ultrasound-mediated drug delivery using ultrasound-responsive nanoparticles.

Ultrasound as a drug-delivery modality offers a number of important advantages over other physical modalities. It can be directed toward deeply located body sites and tumor sonication with millimeter precision is feasible. Sonication may be performed non-invasively or minimally invasively through intraluminal, laparoscopic or percutaneous means. For extracorporeal sonication, the transducer is placed in contact with a water-based gel or a water layer on the skin, and no insertion or surgery is required.

Several mechanisms of ultrasound action in drug-delivery applications have been discussed [29,62,103,152,153]; as mentioned above, both ultrasound-triggered localized drug release from carriers and biological effects of ultrasound should be considered.

Ultrasound as a component of a drug-delivery system may be coupled with a variety of drug carriers. During the last decade, a number of research groups have concentrated their efforts on developing ultrasound-responsive drug carriers for oncological applications [60–62,71,79,80,106,154–160]. On the drug carrier level, local drug release may be activated using carriers that are sensitive to mechanical, thermal or both factors (see below). Ultrasound treatment has also been associated with an induced immune response to tumors [161–164]. In what follows, we will focus on nanocarriers that release their drug load in response to an ultrasound-induced phase shift.

Ultrasound-induced phase-shift emulsions Structural, physical & acoustic properties

It has been known for more than a decade that specially designed PFC droplets can convert into microbubbles under the action of ultrasound irradiation [301]. This effect, termed acoustic droplet vaporization (ADV) has been thoroughly investigated for albumin-coated micron-sized PFC droplets in the works of the University of Michigan group [165–177]. ADV was tested for temporal and spatial control of tissue occlusion [169], as cavitation nucleation agents for nonthermal ultrasound therapy [176,178], for enhancing gene transfer and for phase aberration correction [168].

Kripfgans et al. observed that micrometer-sized droplets can be vaporized into gas bubbles with the application of continuous wave (CW) tonebursts at various frequencies in the diagnostic range (1.5–8 MHz) [167]. The resulting bubbles were 20–80 μm in diameter and could be used for vessel occlusion or phase aberration corrections [168,169]. The threshold for vaporization could be decreased by increasing the frequency [167], increasing the insonation time and introducing microbubbles [171]. The effect of the droplet size on the vaporization threshold has been examined for single droplets of diameters from 5 to 27 μm; the vaporization threshold was higher for smaller droplets [166]. These experiments were recently complemented with optical imaging of the droplet-to-bubble transition using the ultra-high speed imaging [177]. Droplet evolution into bubble is shown in Figure 1 along with a kinetic curve of particle growth.

Figure 1.

(A) Evolution of a 17 μm droplet under the action of a single acoustic pulse of 0.5 MHz focused ultrasound with peak negative acoustic pressures of 4.7 to 10.8 MPa and 3 to 17 cycles in the acoustic pulse. (B) Time line of photographs in microseconds: 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5, 7.5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 120 and 300

Reproduced with permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry from [177].

Experiments performed on the externalized rabbit kidney using albumin-coated dodecafluo-ropentane (DDFP) microdroplets with diameter less than 6 μm showed perfusion reduction of more than 70% following the ADV. The authors hypothesized that this effect may be sufficient for cell death and possible tumor treatment via ischemic necrosis. It was also suggested that radiofrequency ablation of tumors might also benefit from ADV due to reduced perfusion and heat loss. These experiments were later extended to externalized canine kidneys using 3.5 MHz ultrasound [174]. Substantial reduction of cortex perfusion was achieved in some cases. This group later tested in vitro albumin/soybean oil-coated DDFP microdroplets as delivery vehicles for the lipophilic drug chlorambucil [172]. Application of ultrasound-induced ADV almost doubled cell killing by the drug.

For delivering water soluble compounds (fluorescein or thrombin), a double emulsion (W[1]/PFC/W[2]) technique has been developed [173]. Micron-sized, water-in-PFC-in-water (W[1]/PFC/W[2]) emulsions were prepared in a two-step process using PFP or PFH as the PFC phase. Fluorescein or thrombin was contained in the W(1) phase. Double emulsions containing fluorescein in the W(1) phase displayed a 5.7 ± 1.4-fold and 8.2 ± 1.3-fold increase in fluorescein mass flux after ADV for the PFP and PFH emulsions, respectively. Thrombin was stably retained in four out of five double emulsions. For three out of five formulations tested, the clotting time of whole blood decreased in a statistically significant manner when incubated with thrombin-loaded emulsions exposed to ultrasound compared with emulsions not exposed to ultrasound.

To elucidate the physical mechanisms behind ADV, Fabiilli et al. studied the relationship between ADV and IC thresholds by probing the effects of fluid properties (gas saturation, temperature, viscosity and surface tension), and droplet and ultrasound parameters that are known to affect IC [165]. In all of these experiments, the ADV threshold was lower than the IC threshold, indicating that the droplet-to-bubble transition preceded IC. This suggested that for the droplets of micron size used in these works, the mechanism of ADV did not require IC.

This conclusion was recently challenged in the experiments by Schad and Hynynen [179]. The aim of the study was to simultaneously measure the thresholds for vaporization and IC of lipid-encapsulated DDFP droplets of a clinically relevant size. The dependence of these thresholds on droplet size and exposure duration was investigated at acoustic frequencies in the therapeutic range of of 0.578, 1.736 and 2.855 MHz. The mean sizes of the droplets varied from 1.19 to 5.77 μm. The vaporization threshold was found to decrease with increasing droplet size and ultrasound frequency. In contrast, the IC threshold was not significantly dependent on the droplet size and increased with increasing sonication frequency. For sonications of 2.855 MHz all droplets were found to vaporize below the IC threshold (Figure 2A). However, at 1.736 MHz only the large droplets (size > 3.8 μm) vaporized below the IC threshold (Figure 2B). For the smaller sized droplets, IC was detected with or prior to detecting vaporization. At the lowest sonication frequency of 0.578 MHz no bubbles were detected. These results were obtained with room temperature insonation. However at 37°C, all the droplets vaporized without IC. The authors underlined that the results were obtained for insonation times of 10 ms or less and that longer insonation times may yield different results. These results do not rule out the role of IC in promoting droplet vaporization; the data might also suggest that IC may accompany droplet vaporization, that is, start as soon as bubbles are formed.

Figure 2. The effect of the droplet size on the vaporization threshold of lipid-encapsulated dodecafluoropentane droplets sonicated at (A&C) 2.855 MHz and (B&D) 1.736 MHz.

They were measured at (A&B) 22°C and (C&D) 37°C. The inertial cavitation threshold is shown for comparison.

Figure adapted with permission from [179].

In their earlier work, Gieseke and Hynynen measured the IC threshold of micrometer sized albumin-shelled droplets containing different PFC cores (DDFP, PFH or perfluoromethyl-cyclohexane) using passive cavitation detection [180]. The authors found that PFC droplets having contents with higher molecular weights and boiling temperatures did not have detectably higher IC thresholds and, thus, the droplets did not need to be in a superheated state to be cavitated by ultrasound bursts. This was later confirmed in experiments with nanosized per-fluoro-15-crown-5-ether (PFCE) droplets that effectively converted into bubbles at ultrasound pressures that were only slightly higher than those for DDFP nanodroplets [181].

Furthermore, results of Gieseke and Hynynen showed that the cavitation threshold pressure was linearly dependent on the frequency (0.74–3.30 MHz) and not strongly dependent on the burst lengths of 20, 50 or 100 ms [180]. Lo et al. also measured the burst length dependence on IC of micrometer-sized albumin-coated droplets (1.44 MHz, pulse durations from 20 μs to 20 ms) and found that in a short pulse range, the threshold was significantly increased for shorter pulse durations [171]. An advantage to using PFC droplets is that they can be manufactured to sizes as small as 200 nm [182], and thus have the potential to leak out of blood vessels into the interstitial tissue [72,181,183]. Therefore, the ultrasound-induced bioeffects do not have to be constrained to the vasculature.

Kawabata et al. showed that nanometer-sized droplets containing a mixture of DDFP and a hydrogen-containing fluorinated pentane 2H,3H-PFP can be vaporized at diagnostic frequencies (4–7.8MHz) [184]. In addition, the vaporization threshold could be changed by altering the concentrations of the two PFCs in the droplet [185]. In vitro studies with a clinical high-intensity focused ultrasound system showed a 2.5-times increase in temperature elevation when nanodroplets were present [186]. The authors concluded that the vaporization of the higher boiling temperature 2H,3H-PFP may have been due not only to the directly delivered ultrasound energy, but also to the energy deposited by ultrasonically induced bubbles of DDFP.

‘Catalysis’ by the pre-existing microbubbles of the ultrasound-induced droplet-to-bubble transition of nanoscaled DDFP droplets inserted in the gel matrix was observed by Rapoport et al., which suggests that the droplet-to-bubble transition in nanoscaled droplets can be effectively catalyzed not only by mixing PFCs of various boiling temperatures, but also by using a broad or bimodal size distribution of the same PFC [183,187].

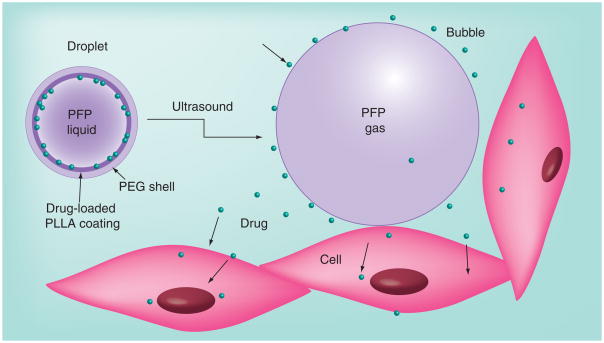

The material presented above implies that drug-loaded, nanoscale droplets could serve as micro-bubble precursors that effectively accumulate in tumor tissue due to their nanoscale sizes and then convert into microbubbles in situ under tumor sonication. This strategy was applied in works by Utah group [63,72,181,187–190]. Drug-loaded phase-shift nanoemulsions were produced from drug-loaded polymeric micelles by introducing PFC compounds into micelle cores (Figure 3). Polymeric micelles are spherical nanoparticles of 20–100 nm size formed in an aqueous medium by self-assembly of amphiphilic block copolymers, that is, PEG-copolylactide (PEG–PLA) or PEG–copolycaprolactone. Polymeric micelles as drug carriers for ultrasound-mediated drug delivery were studied earlier in works by Rapoport et al. [11,151,191–200]. It was demonstrated that drug-loaded polymeric micelles accumulated passively in tumor tissue [155]. Ultrasonic irradiation of the tumor enhanced micelle uptake and resulted in effective intracellular drug internalization by tumor cells. Ultrasound irradiation also enhanced drug diffusion throughout tumor volume, thus reducing drug concentration gradients [11,155,201]. Substantial reduction of the tumor growth rate was achieved using this drug-delivery modality [191,201]. The important drawback of polymeric micelles is their instability upon dilution. When the copolymer concentration drops below the ‘critical micelle concentration’, micelles degrade to individual macromolecules (unimers). Systemic injections are associated with substantial dilutions of injected formulations, which may therefore result in a premature release of the encapsulated drugs. The introduction of highly hydrophobic substances such as PFCs into micelle cores may increase micelle stability due to enhanced physical interaction in the core resulting in a decrease of critical micelle concentration [202].

Figure 3. Drug encapsulated in nanodroplets is localized in nanodroplet shells.

(A) The nanodroplet structure. In nanodroplets, perfluorocarbon compounds form droplet cores while amphiphilic block copolymers form droplet shells that contain two layers. The inner layer is formed by the hydrophobic block of the block copolymer (e.g., polylactide or polycaprolactone) while the outer layer is formed by the hydrophilic block, poly(ethylene oxide). Lipophilic drugs are encapsulated in the hydrophobic inner layer. (B) Laser confocal images of the droplets having the perfluoro-15-crown-5-ether cores and poly(ethlene oxide)-co-polycaprolactone shells with encapsulated doxorubicin. Some micron-scale droplets presented in panel (B) have been specially generated for better visualization of doxorubicin distribution. Doxorubicin localization on the droplet surface is manifested by fluorescence.

To form polymeric nanodroplets, PFC compounds, for example, DDFP, perfluorooctyl-bromide or PFCE, are introduced into micellar solutions and emulsified [63,72,181,190]. At low PFC concentrations, PFC is dissolved in micelle cores. When the PFC concentration exceeds the limit of solubility in a micelle core, the PFC evolves into a separate nanodroplet phase so that the former micelle core turns into a droplet-stabilizing shell. Droplet shells contain two layers: the inner layer formed by the hydrophobic block of the block copolymer (e.g., polylactide or polycapro- lactone), and the outer layer formed by the hydrophilic block, PEG, as shown schematically in Figure 3A. If a lipophilic drug has been encapsulated in micelle cores, the drug is transferred from micelles onto the droplet surface and gets localized in the inner hydrophobic layer of the shell, as exemplified by the laser confocal imaging of DOX encapsulating droplets (Figure 3B). In a range of PFC:copolymer ratios, nano-droplets coexist with copolymer micelles. At high PFC:copolymer ratios, all copolymer may be used for droplet stabilization and only nanodroplets are present in the formulation [63,72,181]. A schematic phase diagram of a PFC–copolymer formulation in aqueous environment is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Representation of the phase diagram of perfluorocarbon–copolymer formulation in aqueous environment: blank purple – micelles; circled purple – droplets.

The dotted line corresponds to critical micelle concentration of copolymer below which neither micelles nor droplets can be formed. Zone 1 corresponds to micellar solutions with perfluorocarbon dissolved in micelle cores; zone 2 corresponds to micelle–droplet mixtures; zone 3 corresponds to droplets only. At a fixed copolymer concentration, transition proceeds from zone 1 to zone 2 to zone 3 upon increasing perfluorocarbon concentration.

Adapted with permission from [63].

A typical protocol for the preparation of a drug (PTX)-loaded block copolymer-stabilized phase-shift nanoemulsion for in vivo application is as follows [181,183]. The PTX containing PEG–PLA micellar solution is first prepared by a solid dispersion technique. 50 mg PEG–PLA and 5 mg PTX are dissolved in 1 ml of tetrahydrofuran. The tetrahydrofuran is then evaporated under gentle nitrogen stream at 60°C. The residual gel matrix is dissolved in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then 10 μl of PFC is introduced into the micellar solution and emulsified by sonication on ice to obtain PTX-loaded nanodroplets. The nanodroplet platform is very versatile allowing variations of the type of PFC, block copolymer or both.

An important advantage of PFC phase-shift nanoemulsions as drug carriers is the ultrasound-induced generation of highly echogenic microbubbles [72,188,190]; PFC nanodroplets are actually theranostic agents that can allow monitoring nanodroplet-based therapy by ultrasound imaging. Under the action of ultrasound, PFC nanodroplets convert into microbubbles, as manifested by the formation of highly echogenic specks in ultrasound images [181,187,190].

The mechanism of the ultrasound-induced droplet-to-bubble transition in PFC phase-shift nanoemulsions is not completely understood. For the PFP, which has a boiling temperature of 29°C at atmospheric pressure, vaporization inside the shell due to physiological temperatures could be one of the mechanisms driving the droplet-to-bubble transition. However, despite their low boiling temperature, DDFP nanodroplets manifest remarkable thermal stability due to the excess pressure exerted by the surface tension on nanodroplets, termed Laplace pressure [187,188,190]. Vaporization temperatures of DDFP droplets of different sizes may be estimated using the Antoine equation (Equation 1) for temperature dependence of vapor pressure, with the coefficients for PFP given in [203]:

| Equation 1 |

where T is absolute temperature and A, B and C are constants. The dependence of a PFP vaporization temperature on droplet size was estimated for two values of surface tension, σ = 30 mN/m and σ = 50 mN/m [187,190]. This estimation showed that at physiological temperature, the droplets with the diameter below 4 μm (for σ = 30 mN/m) or 6.4 μm (for σ = 50 mN/m) have boiling temperatures above physiological temperature and remain in a liquid state, while larger droplets vaporize to form microbubbles. This estimation suggests that, following systemic injection and without the application of ultrasound, nanodroplets remain in a liquid state and therefore retain their nano-scale size, which is important for their extravasation and accumulation in tumor tissue. The accumulation of nanodroplets in tumor tissue after systemic injection was monitored and confirmed by ultrasound imaging of breast [72] and pancreatic tumors [189].

In contrast to DDFP, PFCE has a high boiling temperature of 146°C at atmospheric pressure. However, initiating droplet-to-bubble transition in PFCE nanodroplets required only slightly higher ultrasound energies than those for DDFP [181]. Similar results were obtained earlier by Gieseke and Hynynen for PFC microemulsions made from high boiling-temperature PFCs [180]. A possible mechanism of ultrasound-induced droplet-to-bubble transition in PFCE has been recently suggested by Rapoport et al. [181]. The droplet-to-bubble transition in PFCE nanodroplets occurs not only with CW ultrasound, but also with pulsed ultrasound of the same peak power at a 20% duty cycle and minimal sample heating. This suggests that the droplet-to-bubble transition in PFCE nanodroplets has a nonthermal mechanism. One possible factor involved in acoustically triggered droplet-to-bubble transition nanodroplets is the high solubility of gases, particularly oxygen. This feature has allowed the use of PFC emulsions as blood substitutes [204]. According to Henry’s law, the solubility of gases increases with pressure. It was hypothesized that during the rarefactional phase of ultrasound, the evolution of dissolved oxygen into a gas phase occurred inside the nanodroplet shell, followed by rectified diffusion of dissolved gases from the surrounding liquid into the resulting nanobubble. According to this hypothesis, PFCE bubbles contain a mixture of oxygen and other ambient gases as well as some PFCE vapor in equilibrium with the PFCE liquid phase. When the ultrasound is turned off, equilibrium is restored corresponding to the ambient pressure. The gases with super-equilibrium concentrations diffuse out, thus restoring the PFCE nanodroplets. This hypothesis has been corroborated by the fact that degassing PFCE nanoemulsions inhibited the droplet-to-bubble transition; under ultrasound, no bubbles were formed and droplets remained at the bottom of the test tube; the droplet-to-bubble transition was restored after the contact with air was re-established and a stream of bubbles was rising from the bottom of the tube. The cycles of inhibition/induction of bubble formation could be repeated indefinitely.

The mechanism of the bubble formation described above is different from real vaporization of droplets. However, independent of the specific mechanism of droplet-to-bubble transition, the effects associated with microbubble cavitation in the ultrasound field will be exerted on the nanodroplets and biological tissue.

Bubbles formed from DDFP or PFCE nano-droplets were indeed shown to oscillate and cavitate in the ultrasound field, as manifested by the generation of harmonic, sub-harmonic frequencies and broadband noise in the fast Fourier transform spectra of the scattered ultrasound beam [181,188,190]. Although the oscillation amplitudes were somewhat smaller for PFCE than for DDFP, PFCE bubbles clearly underwent stable cavitation both in liquid emulsions and gel matrices. Larger differences between DDFP and PFCE bubbles were observed for broadband noise, indicating that PFCE bubbles were less susceptible to IC. Droplet-to-bubble transitions and bubble oscillations result in enhanced absorption of ultrasound energy and sample heating. This was demonstrated for PFCE nanodroplets in vitro and in vivo [181].

Therapeutic outcomes & anticipated mechanisms

Successful ultrasound-triggered delivery of PTX to monolayers of prostate cancer cells from a phospholipid-coated PFH nanoemulsion developed by ImaRx was reported in vitro [60]. In publications by Lanza et al. a strong therapeutic effect was achieved for tumor treatment by drug-loaded lipid-stabilized perfluorooctyl-bromide or PFCE perfluorocarbon nanoemul-sions and ultrasound [205–208]. The mechanism of ultrasound-mediated drug delivery proposed by the authors was based on the radiation force-enhanced droplet–cell contact and delivery rather than droplet-to-bubble transition. According to this mechanism, ultrasound application enhanced contact and fusion of cell membranes and phospholipid-coated nanodroplets, resulting in the transfer of drug from nanodroplet shells into the interior of the cell for effective tumor therapy. This mechanism is different from that proposed by Rapoport et al. for block copolymer-coated PFC nanoemulsions [190], which is based on droplet-to-bubble transition as presented in Figure 5. Upon droplet-to-bubble transition, the particle volume increases dramatically, which is accompanied by a decrease of the thickness of the droplet shell. For a 500 nm DDFP droplet where actual vaporization (i.e., liquid-to-vapor transition of the PFC) can be expected, it was estimated that an initial shell thickness of 30 nm dropped to 1.2 nm upon complete droplet vaporization. This is expected to favor the release of encapsulated drug, especially under the ultrasound action that ‘rips off’ drug from the surface. In addition, the increase of surface area decreases copolymer concentration on the surface and may even create ‘naked’ patches that would also facilitate drug release.

Figure 5. Drug transfer from droplets to bubbles to cells under the action of ultrasound.

PFP: Perfluoropentane; PLLA: Poly(L-lactide); PEG: Poly(ethylene oxide). Adapted with permission from [190]. © Elsevier.

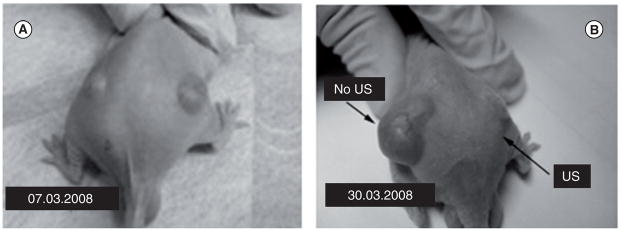

The therapeutic properties of drug-loaded DDFP and PFCE nanodroplets combined with 1 MHz ultrasound were reported in detail [181,190]. Important information was provided by a pilot experiment where bi-lateral ovarian carcinoma tumors inoculated in a nude mouse were used (Figure 6). This mouse was treated by four systemic injections of nanodroplet-encapsulated PTX (20 mg/kg as PTX) given twice weekly; only one (the right) tumor was sonicated by 1 MHz CW ultrasound at a nominal output power density 3.4 W/cm2 with exposure duration of 1 min. Ultrasound was delivered 4.5 h after the injection of the drug formulation. The unsonicated left tumor grew at the same rate as control tumors. In contrast, the sonicated tumor appeared completely resolved after four treatments. This data suggested that without ultrasound, the drug (PTX) was tightly retained inside the DDFP droplet walls, but was effectively released under the action of tumor-directed therapeutic ultrasound. Tight drug retention by the nanodroplet carrier in vivo is expected to provide protection for healthy tissues. On the other hand, effective ultrasound-induced PTX release into the tumor volume results in efficient tumor regression.

Figure 6. Mouse was treated by four systemic injections of nanodroplet-encapsulated paclitaxel (20 mg/kg as paclitaxel) given twice weekly.

Only one tumor was sonicated (1 MHz continuous wave ultrasound at a nominal output power density 3.4 W/cm2, exposure duration 1 min; ultrasound was delivered 4.5 h after the injection of the drug formulation). (A) The tumor grew at the same rate as untreated control tumors while in (B) the tumor appeared completely resolved.

Adapted with permission from [190]. © Elsevier.

The effects of empty (i.e., not drug loaded) and PTX-loaded PFCE nanodroplets were compared in experiments with pancreatic tumor-bearing mice. Tumors were transfected with red fluorescence protein in order to allow intravital imaging. Cell survival monitoring was based on the fact that dead cells lose fluorescence. Tumors were sonicated using a focused ultrasound transducer under the MRI control with temperature monitored during treatment using MRI thermometry [181]. In this and similar experiments, no trace of cell death was observed in the tumor fluorescence images of mice injected with empty nanodroplets. In contrast, cell death was clearly manifested in tumor fluorescence images of mice injected with PTX-loaded nanodroplets (Figure 7A & B). The dark area of nonviable cells (~4 mm diameter ‘crater’) corresponded to the focused ultrasound treated area. A significant delay of tumor growth was observed in a mouse treated with PTX-loaded phase-shift nano-emulsions combined with focused ultrasound despite the fact that only a fraction of the total tumor volume was treated by ultrasound.

Figure 7. Intravital fluorescence images of subcutaneous pancreatic tumors (A) before and (B) 3 days after focused ultrasound treatment.

A mouse was injected with paclitaxel-loaded droplets 1%perfluoro-15-crown-5-ether/5% poly(ethylene oxide)–PDLA droplets 6 h before ultrasound treatment; drug dose was 40 mg/kg. Conditions of ultrasound treatment: ultrasound beam was steered for 50 s in a circle 4 mm diameter (8 ‘points’, 200 ms/point, 30 circles per treatment resulting in a total 6 s sonication of each ‘point’ with a maximum power density in the focal zone of 54 W/cm2). MRI thermometry showed tumor heating by approximately 10°C.

These and similar results suggest that:

The therapeutic action resulted from the action of drug rather than mechanical or thermal cell killing by ultrasound;

The therapeutic action of nanodroplet-encapsulated drug was substantially enhanced by ultrasound whether this was a result of enhanced nanodroplet extravasation, ultrasound-triggered drug release from nanodroplets, hyperthermia effect caused by a 10°C additional heating, intracellular droplet and drug uptake, or all of the above;

The delayed tumor growth in the PTX-treated mouse suggested that although a small fraction of the tumor was treated with ultrasound, drug was spread throughout the tumor volume by enhanced convection or diffusion.

A strong therapeutic effect was also observed for a breast cancer treatment with PFCE/PEG–PDLA nanodroplet-encapsulated PTX and focused ultrasound as demonstrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Dramatic regression of a breast cancer MDA MB231 tumor treated by four systemic injections of paclitaxel-loaded 1% perfluoro-15-crown-5-ether/0.25% poly(ethylene oxide)-co-polycaprolactone nanoemulsion and focused 1 MHz continuous-wave ultrasound applied for 60 s.

Paclitaxel dose was 40 mg/kg.

Figure adapted with permission from [181]. © Elsevier.

Promising in vitro results using ultrasound-activated PFC nanodroplets were obtained with delivery of another chemotherapeutic drug, camptothecin [209]. Camptothecin is a topo-isomerase I inhibitor that acts against a broad spectrum of cancers. However, its clinical application is limited by its insolubility, instability and toxicity. Fang et al. developed acoustically active captothecin nanoemulsions using liquid PFCs and coconut oil as the droplet cores. These nanoemulsions were stabilized by phospholipids and/or Pluronic F68. The formulations allowed a very high degree of drug loading (~100%) and manifested a mean droplet diameter of 220–420 nm. Confocal laser scanning microscopy confirmed nanoemulsion uptake into cells. Camptothecin in these systems showed retarded drug release; the release was enhanced by 1 MHz ultrasound. The formulations demonstrated cytotoxicity against melanomas and ovarian cancer cells. The same group tested acoustically active PFC nanoemulsions for delivery of a dopamine receptor agonist, apomorphine, for treating Parkinson’s disease [209]. Clinical application of apomorphine is limited by its instability and the need for frequent injections. The apomorphine nanoemulsions have been developed using coconut oil and PFP as the core, and phospholipids and cholesterol as the shell components. The particle size ranged from 150–380 nm, with differences in the oil or PFC ratio in the formulations. The stability experiments showed that apomorphine in nanodroplets was protected from degradation. Retarded- and sustained-release profiles were observed. The release rate was enhanced two- to four-fold with the application of 1 MHz ultrasound. Recently, phase-shift DDFP nanoemulsions attracted attention as potential nucleation agents for bubble-enhanced high intensity focused ultrasound HIFU tumor ablation [175]. Taken together, these results suggest drug-loaded PFC phase-shift nanoemulsion in combination with ultrasound treatment can provide efficient therapy for a broad spectrum of diseases.

Lasers & drug delivery

A rapidly maturing method for introducing targeted energy into tissue makes use of lasers and fiber optics. Laser technology, due to the optical scattering properties of tissue, will never be as non-invasive as ultrasound; however, the ability to introduce incredibly high power densities through modern optical fiber technology makes laser a very attractive, minimally invasive alternative. In fact, laser ablation is already being considered for brain, liver and prostate cancer [210–212]. Laser energy is absorbed by various endogenous dyes and molecules, particularly hemoglobin, and this forms the basis of ablation and heating of normal tissues. The thermoacoustic signal derived from the rapid expansion of laser-heated blood is the basis of most photoacoustic imaging [213,214]. It is also possible to introduce laser absorbing dyes or nanoparticles to concentrate the energy absorption in particular locations. One of the best absorbers of laser energy is the plasmonic gold nanoparticle (GNP). Gold nanospheres, which typically range in size from 30 to 150 nm in diameter, are known to resonantly absorb light in the 530 nm wavelength range. Modification of the nanoparticle shape has been used to shift this resonance further to the near infrared (NIR, 800 nm), where absorption and scattering is minimal in tissue [215]. A number of groups are focused on using plasmonic nanoparticles as a way of inducing a spatially tailored hyperthermia or thermal ablation in the vicinity of tumors or other malignancies [18,19,216,217]. Lower power continuous laser sources are ideal for this type of application as they are readily available, easy to work with, and millimeter scale heating is best induced with high average power deposition, with no added benefit from the high instantaneous powers such as may be produced by pulsed laser. On the other hand, the phase-shift plasmonic nanobubble described in detail below takes full advantage of the available power output of the laser and the targeting of plasmonic nanoparticles for control at the nanoscale.

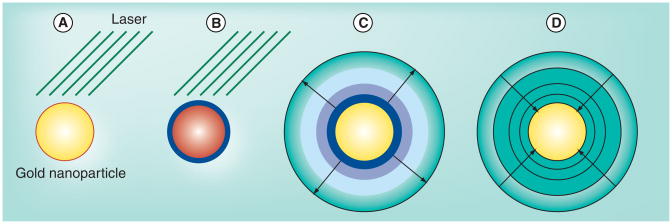

Laser-induced phase-shift plasmonic nanobubbles

It is well known that high-intensity focused laser pulses may be used to create sub-microscopic vapor bubbles in liquids, an effect that has been used in biological applications for some time [218,219]. A better result may be achieved by targeting plasmonic nanoparticles. Plasmonic nanoparticles, such as a gold nanospheres, nanoshells or nanorods, acted on by a high power laser pulse will rapidly produce a vapor bubble from the surrounding liquid medium. The resulting gas bubble is sometimes called a ‘plasmonic nanobubble’ [220]. The basic physical principle behind this process is clear, although the details are poorly understood. The main condition is that the energy deposition into the nanoparticle should be sufficiently rapid to overwhelm the rapid cooling provided by thermal diffusion at the resulting high temperature gradient [221] as well as the latent heat of evaporation [221,222]. For a GNP of radius 25 nm in water, for example, energy deposition must be on the order of 109 W/m2 [222]. Currently, this power deposition is easily achieved only with lasers. The use of plasmonic nanoparticles, such as gold nanospheres, rather than endogenous dyes, such as hemoglobin, makes this process both more efficient and more local. Such a system is capable of nucleating a nanobubble in the immediate vicinity of the nanoparticle in as little as a few femtoseconds (fs) [221]. Once the internal thermally driven pressure of this nano-bubble exceeds the surface tension and pressure in the liquid, it expands adiabatically to a size ultimately dictated by the total energy in the system. This process typically takes some tens of nanoseconds, which is often much longer than the laser pulse duration [221]. The nanobubble then shrinks as the medium rapidly cools and returns to liquid phase (Figure 9). Because the bubble lifetime is extremely short, it is thought that there is no time for any of the resonant phenomena often associated with bubbles in a liquid medium, such as inertial collapse [221]. The net heat deposition is very small, but very local; once dispersed, the temperature rise in the surrounding medium is negligible [222].

Figure 9. Growth and collapse of a plasmonic nanobubble.

(A) Gold nanoparticle is rapidly heated by laser matched to its plasmon resonance frequency. (B) A thin shell of water vapor appears at hot surface. (C) Water vapor rapidly expands against pressure of liquid water even as the laser pulse is turned off and nanoparticle rapidly cools. (D) Cooling water vapor contracts.

Much work has been done by the Rice University group of Lapotko et al., focusing on the dynamics of single nanobubble formation around nanoparticles and clusters of nano-particles [198–209]. This has allowed for characterization of the activation thresholds in terms of laser power and fluence, GNP size, shape and aggregation, and the affects of these parameters on nanobubble lifetime and size, and finally, their interactions with cells [221,223–231]. Their experimental design used the strong light scattering from single nanobubbles as a means of detection and characterization. Photo-acoustic detection and characterization should also be possible. The results of these studies suggest there is a laser fluence and power threshold above which nonthermal nanobubbles are formed, and that gold particle clustering dramatically reduces the threshold for nanobubble production. This latter fact can be utilized for cell selectivity, since endocytosed GNPs are typically found in clusters. While the goal of Lapotko’s work has been directed mainly towards single-cell ablation rather than drug delivery, many of the same physical principles are useful in both cases.

A potential alternative to this approach that may allow vaporization at lower powers is to combine light-absorbing nanoparticles inside PFP droplets. The vaporization is thus initiated at the lower energies required for PFP evaporation. This approach has recently been demonstrated in micron-sized PFP droplets loaded with PbS–silicon nano-absorbers [232], but it remains to be seen whether it will also be feasible with nanoscale PFP droplets, potentially allowing for dual or complementary targeting techniques.

Plasmonic nanobubbles & drug delivery

Plasmonic nanobubbles may potentially be useful for enhancing gene and drug delivery in two ways, first, by mechanical interaction with cells, and second, by mechanical interaction with a drug carrier. In the first case, the bubbles may be used as a means of reversibly disrupting cellular and intracellular membranes, which might be thought of as a type of sonoporation. Lapotko et al. demonstrated uptake of cell-membrane impermeable ethidium bromide in single cells located in close contact with GNPs acted on by a laser pulse [229]. By controlling the pulse fluence, they were able to control the amount of damage done to the cell. Follow-up studies demonstrated targeted green fluorescent protein transfection of individual cancer cells carrying particular receptors (CD-43, CD117) by using antibody-conjugated GNPs and laser. Preferential endocytosis of the nanoparticles by the receptor-positive cells and subsequent nanobubble production with lower fluence laser pulses resulted in pore formation only in these cells due to the lowered threshold associated with nanoparticle clusters. The green fluorescent protein plasmid was believed to enter the cell not only by diffusion through the resulting pore, but also by the pumping action of the collapsing nanobubble [228]. Following treatment, cell viability remained high.

Since plasmonic nanoparticles are readily endocytosed by a variety of cells, they may be used to promote selective release of endosomal contents via generation of plasmonic nano-bubbles. Endosomal release remains a significant problem for macromolecular drug, gene or siRNA delivery. While endocytosis is an efficient means of cellular delivery for many macromolecules, it often does not result in effective therapy because the internalized macromolecules remain sequestered in endosomes and are eventually exocytosed. By producing a plasmonic nanobubble from GNPs inside the endosome, the endosome may be mechanically disrupted and its contents released into the cytoplasm. The control over this process is such that this should be possible without permanently damaging or killing the cell.

A similar process may be used to deliver drug from an encapsulating delivery vehicle. A number of groups have demonstrated this method [220,233,234], while others, notably Paasonen [43,235] and Volodkin [236] have used related techniques. While Paasonen and Volodkin both demonstrated release from liposome/GNPs collections, it is clear from the release dynamics (>30 min) that Paasonen’s technique relied exclusively on thermal effects; Volodkin has never clearly addressed the issue of mechanism, to the best of our knowledge. In his work, release was fast enough to be bubble related, but he used CW rather than pulsed laser, so it was not obvious which mechanism was operative. Of the three papers that explicitly relied on nanobubble production, the earliest results were published by Wu et al. in 2008 [233]. In that paper, a quenched dye (6-carboxyfluoroscien) was encapsulated inside micron-sized DPPC liposomes. Hollow gold nanoshells (33 nm diameter, resonant at 820 nm laser wavelength) were located inside the liposome, conjugated to the liposome surface, or suspended outside the liposome. An 800 nm, a 130 fs laser pulse was used on the solution, and 6-carboxyfluoroscien release was measured by the increase in fluorescence relative to a positive control where the liposomes were chemically lysed. Acoustic emission was also measured during treatment. Release was observed at laser fluence greater than approximately 2.2 mJ/cm2 (reported in the paper as average power density of 2.2 W/cm2 at 1 kHz; peak power density ~1010 W/cm2). This was correlated to a sudden jump in broadband acoustic emission signal. Both the discontinuity of acoustic emission as a threshold power is reached and the broadband nature of the received signal suggested the onset of thermally induced cavitation, indicating the mechanism of release was indeed related to bubble production [233]. Some release could be found with nanoshells in all three locations tested, however, it was most efficient for conjugated nanoparticles (93%). Electron microscopy following treatment demonstrated that the gold nanoshells had completely melted, leaving behind solid gold spheres.

Anderson et al. (Rice group [220]) used similarly sized liposomes (combination of 80% 1, 2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) and 20% 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethyl-ammonium-propane (DOTAP), but considered only encapsulation of solid gold nanospheres (80 nm diameter) and 532 nm pulsed laser (0.5 ns pulse length, fluence 0.01–1 J/cm2; peak power density 107–109 W/cm2). GNPs and nanoparticle clusters inside liposomes were found using scattered light under dark-field microscopy, and the release of a fluorescent dye (not quenched) was directly observed with microscopy. Using their setup, Anderson was able to observe release from single liposomes while monitoring nanobubble lifetime during single laser pulses using a laser light scattering detection system. They demonstrated that release was immediate (ejection rather than diffusion), that the threshold for release was lower for larger clusters, and that larger nanobubbles could induce total destruction of the liposome and ejection of all contents.

Qin et al. achieved a similar result using 532 nm, 6 ns pulsed laser (average power density 3.3 W/cm2 at 10 Hz; peak power density of 5.5 × 107 W/cm2) to release radionuclides (Tc-99m mebrofenin), fluorescent dyes (calcein), and the fluorescent chemotherapeutic, doxorubicin, from 100 nm diameter partially polymerized liposomes conjugated to gold (PPL–GNP; Figure 10) [234]. These hybrid liposomes were shown to be more stable under physiological temperatures than the normal 1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) or thermally sensitive liposomes. Solid GNPs (50 nm) were conjugated on the outside surface of the PPL, at a ratio of approximately one GNP per PPL. Release of approximately 70% of the encapsulated contents was measured in vitro for both Tc-99m and calcein, compared with a chemically lysed control. Notably, the same laser pulse at 1064 nm wavelength had no impact on the liposomes. In cell culture, doxorubicin-encapsulating PPL–GNPs that were incubated with a breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231) and treated with laser pulses demonstrated excellent cytotoxicity. In contrast, control groups treated with either laser alone, with the PPL–GNP without laser, or with just laser and GNP remained viable. Confocal microscopy demonstrated that without the laser pulse, PPL–GNP were found in the cytoplasm of the cells, however, the drug carriers remained intact and the doxorubicin did not penetrate to the nucleus. Following pulsed laser treatment, however, free doxorubicin was found concentrated in the cell nucleus [234]. TEM from the cells before and after laser pulse treatments demonstrated that the GNPs were completely destroyed during laser treatment, most likely by melting and reforming into smaller particles, strongly suggesting that nanobubbles were involved in the process of releasing the drug.

Figure 10. A plasmonic nanobubble is used to release drug from a partially polymerized liposome nanocapsule according to Qin et al.

[234]. Laser-absorbing gold is covalently linked to the partially polymerized shell of the liposome containing the drug (doxorubicin). A single laser pulse creates a rapidly expanding nanobubble of water vapor that destroys some part of the capsule, releasing the contents.

Safety issues

As discussed above, application of nanoparticles in biological systems opens up new directions for medical treatments. However, there has been public concern on the safety of nanomaterials, especially for inorganic nanomaterials, as the interaction of particles with biological systems unravels a series of new mechanisms not found for moleculary dispersed agents: altered biodistribution, chemically reactive interfaces, and the combination of solid-state properties and mobility, High aspect ratio materials such as carbon nanotubes, nanorods, nanowires and other nanofibers are being used on an increasingly large scale and require toxicological scrutiny. The long-term safety of nanoparticles and the role of inertness and bioaccumulation were discussed in a number of recent reviews [237–240]. However, the major risk is associated with the unintended exposure to nanoparticles rather than their strictly regulated medical use.

Future perspective

Controlled drug delivery has been an elusive goal of the medical engineering community ever since the ‘magic bullet’ concept was first articulated over a century ago. It is now clear that this goal will likely only be achieved by an appropriate combination of tissue preparation, tissue targeting and active release mechanisms. The application of targeted physical energies, including ultrasound and laser, has a role to play in overcoming transport barriers at multiple scales from the tissue level down to the intracellular level. As well, these energies allow direct control over drug carriers designed to respond to them. Phase-shift nanoparticles display high promise compared with other technologies due to high localizability and responsiveness to external stimuli. Whether ultrasound or laser induced, the micro- and nano-bubbles produced by these particle-stimulus combinations represent a focal delivery of energy that has unmatched local specificity and power. Tapping this power, researchers have already demonstrated significant tissue, cellular and intracellular level control of drug delivery. However, we are barely scratching the surface of what may be accomplished with this control. Such nanoparticles have yet to take serious advantage of imaging technologies such as PET, or MRI (although the ultrasound responsive nanodroplets are clearly ahead in this sense) or active molecular targeting, and much in vivo work remains. It is only in vivo that the practical potentials and limitations of each technology will ultimately need to be discovered. Although many will begin by treating ultrasound and laser phase-shift technologies as competitive, in the body they are complementary. Laser catheters should easily reach those areas, such as lung or bowel, where ultrasound is blocked by voids or bone. Conversely, ultrasound will work best in bulk tissues where a laser would be too invasive. These technologies in combination will almost certainly play a key role in bringing intelligent design principles to the drug-delivery problem and ultimately reducing the costs of human suffering from unwanted and uncontrolled side effects.

Executive summary.

Mechanisms of targeted drug delivery include the localized thermal and mechanical action of directed energies on biological tissues and drug-carrying nanoparticles. An unprecedented opportunity to localize drug delivery is associated with developing stimulus-responsive drug carriers, particularly ultrasound- and laser light-responsive nanoparticles.

Ultrasound-responsive drug carriers include phase-shift liposomes and perfluorocarbon nanoemulsions that respond to thermal and mechanical modes of ultrasound action, respectively. Light-responsive drug carriers are usually a combination of plasmonic nanoparticles of various geometries and polymer- or lipid-drug capsule that may be opened by temperature or pressure changes. These novel technologies have demonstrated excellent therapeutic potential in murine cancer models.

Phase-shift nanoparticles such as ultrasound-responsive nanodroplets or laser-induced plasmonic nanobubbles have the potential to produce very strong, highly localized effects. These systems are capable of employing a wide variety of the known drug-delivery mechanisms and strategies to produce effects at the tissue, cellular and intracellular level. They are also ideal for functionalization as actively targeted agents or as therapy-plus-imaging (theranostic) probes.

Introducing phase-shift nanoparticles into clinical practice requires transition to experiments on larger animals. Passive targeting of nanoparticles may be more challenging in larger animals and humans than in small-animal models due to much smaller tumor-to-body volume ratio in large animals. Identifying more selective surface receptors is a crucial task for active targeting. These problems remain to be addressed in future translational studies.

Image guidance of drug delivery that involves the identification of targets and tracking delivery systems in the body, guidance of therapy, and monitoring of immediate and delayed therapeutic response will be critical for design of optimal clinical drug-delivery systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dmitri Lapotko and other outstanding scientists, many cited here only in passing, for many enlightening discussions regarding their work.

Key Terms

- Targeted drug delivery

Concept of rational control to ensure maximum accumulation of drugs in target (diseased) tissue and a minimum of systemic accumulation to avoid unintended side effects

- Phase shift

Change of state induced by applying energy; in this context production of a gas bubble from a liquid based on applied ultrasound or laser energy

- Plasmonic nanoparticles

Nanoparticles, usually gold or other metals, that exhibit a plasmon resonance allowing them to effectively absorb electromagnetic energy at specific UV, visible or infrared wavelengths determined by their geometry, such as nanospheres, nanorods, nanoshells and nanocages

- Perfluorocarbon nanodroplets

Submicron diameter droplets of liquid perfluorocarbon stabilized by a shell of polymer, protein or lipid

- Ultrasound-induced phase shift

Droplet-to-bubble transition resulting from the action of ultrasound on nano- or micro-droplets

- Droplet-to-bubble transition

Liquid-to-gas phase change brought about in perfluorocarbon nanodroplets by changes in temperature or pressure

- Phase-shift nanoemulsions

Aqueous suspension of stabilized perfluorocarbon nanodroplets, possibly loaded with a drug, that are capable of conversion to gas phase under the action of ultrasound

- Plasmonic nanobubble

Short-lived bubble of water vapor produced by the rapid heating of a suspended plasmonic nanoparticle with laser irradiation

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact reprints@future-science.com

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This paper was funding in part through NIH grant R01 EB1033 (Natalya Rapoport). Natalya Rapoport has a number of patent applications submitted and pending for approval. Brian O’Neill is the co-inventor of the gold conjugated partially polymerized liposomes mentioned in the article. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

- 1.Hahn MA, Singh AK, Sharma P, Brown SC, Moudgil BM. Nanoparticles as contrast agents for in-vivo bioimaging: current status and future perspectives. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;399(1):3–27. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janib SM, Moses AS, MacKay JA. Imaging and drug delivery using theranostic nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(11):1052–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie J, Lee S, Chen X. Nanoparticle-based theranostic agents. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(11):1064–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCarthy JR. Multifunctional agents for concurrent imaging and therapy in cardiovascular disease. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(11):1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan D, Lanza GM, Wickline SA, Caruthers SD. Nanomedicine: perspective and promises with ligand-directed molecular imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70(2):274–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iyer AK, Khaled G, Fang J, Maeda H. Exploiting the enhanced permeability and retention effect for tumor targeting. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11(17–18):812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell RB. Tumor physiology and delivery of nanopharmaceuticals. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2006;6(6):503–512. doi: 10.2174/187152006778699077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hobbs SK, Monsky WL, Yuan F, et al. Regulation of transport pathways in tumor vessels: role of tumor type and microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(8):4607–4612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohner M, Ring TA, Rapoport N, Caldwell KD. Fibrinogen adsorption by PS latex particles coated with various amounts of a PEO/PPO/PEO triblock copolymer. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2002;13(6):733–746. doi: 10.1163/156856202320269184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan JS, Butterfield DE, Voycheck CL, Caldwell KD, Li JT. Surface modification of nanoparticles by PEO/PPO block copolymers to minimize interactions with blood components and prolong blood circulation in rats. Biomaterials. 1993;14(11):823–833. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(93)90004-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rapoport N. Physical stimuli-responsive polymeric micelles for anti-cancer drug delivery. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:962–990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacEwan S, Callahan D, Chilkoty A. Stimulus-responsive macromolecules and nanoparticles for cancer drug delivery. Nanomedicine. 2010;5(5):793–806. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreher MR, Liu W, Michelich CR, Dewhirst MW, Yuan F, Chilkoti A. Tumor vascular permeability, accumulation, and penetration of macromolecular drug carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(5):335–344. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong G, Braun RD, Dewhirst MW. Hyperthermia enables tumor-specific nanoparticle delivery: effect of particle size. Cancer Res. 2000;60(16):4440–4445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong G, Braun RD, Dewhirst MW. Characterization of the effect of hyperthermia on nanoparticle extravasation from tumor vasculature. Cancer Res. 2001;61(7):3027–3032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayat H, Friedberg I. Heat-induced alterations in cell membrane permeability and cell inactivation of transformed mouse fibroblasts. Int J Hyperthermia. 1986;2(4):369–378. doi: 10.3109/02656738609004967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krupka T, Dremann D, Exner A. Time and dose dependence of pluronic bioactivity in hyperthermia-induced tumor cell death. Exp Biol Med. 2009;234(1):95–104. doi: 10.3181/0807-RM-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott AM, Stafford RJ, Schwartz J, et al. Laser-induced thermal response and characterization of nanoparticles for cancer treatment using magnetic resonance thermal imaging. Med Phys. 2007;34(7):3102–3108. doi: 10.1118/1.2733801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang HC, Rege K, Heys JJ. Spatiotemporal temperature distribution and cancer cell death in response to extracellular hyperthermia induced by gold nanorods. ACS Nano. 2010;4(5):2892–2900. doi: 10.1021/nn901884d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glazer ES, Curley SA. Radiofrequency field-induced thermal cytotoxicity in cancer cells treated with fluorescent nanoparticles. Cancer. 2010;116(13):3285–3293. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cardinal J, Klune JR, Chory E, et al. Noninvasive radiofrequency ablation of cancer targeted by gold nanoparticles. Surgery. 2008;144(2):125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cole AJ, Yang VC, David AE. Cancer theranostics: the rise of targeted magnetic nanoparticles. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shubayev VI, Pisanic TR, 2nd, Jin S. Magnetic nanoparticles for theragnostics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61(6):467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponce AM, Vujaskovic Z, Yuan F, Needham D, Dewhirst MW. Hyperthermia mediated liposomal drug delivery. Int J Hyperthermia. 2006;22(3):205–213. doi: 10.1080/02656730600582956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kong G, Anyarambhatla G, Petros WP, et al. Efficacy of liposomes and hyperthermia in a human tumor xenograft model: importance of triggered drug release. Cancer Res. 2000;60(24):6950–6957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ponce AM, Viglianti BL, Yu D, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of temperature-sensitive liposome release: drug dose painting and antitumor effects. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:53–63. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poon RTP, Borys N. Lyso-thermosensitive liposomal doxorubicin: a novel approach to enhance efficacy of thermal ablation of liver cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(2):333–343. doi: 10.1517/14656560802677874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hauck ML, LaRue SM, Petros WP, et al. Phase I trial of doxorubicin-containing low temperature sensitive liposomes in spontaneous canine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(13):4004–4010. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deckers R, Moonen CT. Ultrasound triggered, image guided, local drug delivery. J Control Release. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.07.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dromi S, Frenkel V, Luk A, et al. Pulsed-high intensity focused ultrasound and low temperature-sensitive liposomes for enhanced targeted drug delivery and antitumor effect. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(9):2722–2727. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stone MJ, Frenkel V, Dromi S, et al. Pulsed-high intensity focused ultrasound enhanced tPA mediated thrombolysis in a novel in vivo clot model, a pilot study. Thromb Res. 2007;121(2):193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Negussie AH, Yarmolenko PS, Partanen A, et al. Formulation and characterisation of magnetic resonance imageable thermally sensitive liposomes for use with magnetic resonance-guided high intensity focused ultrasound. Int J Hyperthermia. 2011;27(2):140–155. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2010.528140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staruch R, Chopra R, Hynynen K. Localised drug release using MRI-controlled focused ultrasound hyperthermia. Int J Hyperthermia. 2011;27(2):156–171. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2010.518198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pissuwan D, Niidome T, Cortie MB. The forthcoming applications of gold nanoparticles in drug and gene delivery systems. J Control Release. 2011;149(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang F, Wang Y-C, Dou S, Xiong M-H, Sun T-M, Wang J. Doxorubicin-tethered responsive gold nanoparticles facilitate intracellular drug delivery for overcoming multidrug resistance in cancer cells. ACS Nano. 2011 doi: 10.1021/nn200007z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wijaya A, Schaffer SB, Pallares IG, Hamad-Schifferli K. Selective release of multiple DNA oligonucleotides from gold nanorods. ACS Nano. 2009;3(1):80–86. doi: 10.1021/nn800702n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skirtach AG, Dejugnat C, Braun D, et al. The role of metal nanoparticles in remote release of encapsulated materials. Nano Lett. 2005;5(7):1371–1377. doi: 10.1021/nl050693n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.An X, Zhang F, Zhu Y, Shen W. Photoinduced drug release from thermosensitive AuNPs-liposome using a AuNPs-switch. Chem Commun. 2010;46(38):7202–7204. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03142a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angelatos AS, Radt B, Caruso F. Light-responsive polyelectrolyte/gold nanoparticle microcapsules. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109(7):3071–3076. doi: 10.1021/jp045070x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duncan B, Kim C, Rotello VM. Gold nanoparticle platforms as drug and biomacromolecule delivery systems. J Control Release. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang H, Liu H, Zhang X, et al. Photoresponsive DNA-cross-linked hydrogels for controllable release and cancer therapy. Langmuir. 2011;27(1):399–408. doi: 10.1021/la1037553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asadishad B, Vossoughi M, Alamzadeh I. In vitro release behavior and cytotoxicity of doxorubicin-loaded gold nanoparticles in cancerous cells. Biotechnol Lett. 2010;32(5):649–654. doi: 10.1007/s10529-010-0208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paasonen L, Sipilä T, Subrizi A, et al. Gold-embedded photosensitive liposomes for drug delivery: triggering mechanism and intracellular release. J Control Release. 2010;147(1):136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agasti SS, Chompoosor A, You C-C, Ghosh P, Kim CK, Rotello VM. Photoregulated release of caged anticancer drugs from gold nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(16):5728–5729. doi: 10.1021/ja900591t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Das M, Sanson N, Fava D, Kumacheva E. Microgels loaded with gold nanorods: photothermally triggered volume transitions under physiological conditions. Langmuir. 2007;23(1):196–201. doi: 10.1021/la061596s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]