Abstract

Purpose

To (1) clarify the role of various risk factors in the development of ASD, (2) compare instrumentation configuration with the development of ASD, (3) correlate the radiological incidence of ASD and its clinical outcome and (4) compare the clinical outcome between patients with radiological evidence of ASD and without ASD.

Methods

This study prospectively examined 74 consecutive patients who underwent instrumented lumbar/lumbosacral fusion for degenerative disease with a minimum follow-up of 5 years. Among the patients, 68 were enrolled in the study. All of the patients had undergone preoperative radiological assessment and postoperative radiological assessment at regular intervals. The onset and progression of ASD changes were evaluated. The patients were divided in two groups: patients with radiographic evidence of ASD (group 1) and patients without ASD changes (group 2). Comprehensive analysis of various risk factors between group 1 and group 2 patients was performed. The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was used to evaluate the clinical outcome and the functional outcome was evaluated using the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) before and after surgery along with radiological assessment.

Results

Radiographic ASD occurred in 20.6% (14/68) of patients. Preoperative disc degeneration at an adjacent segment was a significant risk factor for ASD. Other risk factors such as the age of a patient at the time of surgery, gender, preoperative diagnosis, length of fusion, instrumentation configuration, sagittal alignment and lumbar or lumbosacral fusion were not significant risk factors for the development of ASD. There was no correlation between ASD and its clinical outcome as determined at the final follow-up session. In addition, clinical outcome of patients with ASD and without ASD were not comparable.

Conclusions

Patients with preoperative disc degeneration at an adjacent segment were more at risk for the development of ASD. Other risk factors including instrumentation configuration were not significantly associated with ASD. There was no correlation between both the radiological development of ASD and its clinical outcome and the clinical outcome of patients with and without ASD.

Keywords: Adjacent segment degeneration, Instrumented lumbar fusion, Risk factors

Introduction

Lumbar or lumbosacral instrumented fusion is increasingly performed as the treatment of choice for various degenerative disorders of the lumbar spine. Different methods to achieve fusion have developed over the period of the last two to three decades, ranging from posterior midline fusion to instrumented posterolateral fusion with or without intervertebral body fusion. Rigid fixation with instrumentation allows early activity/rehabilitation and is more likely to promote successful fusion. After instrumented spinal fusion, however, compensatory mechanical changes are inevitable at adjacent segments, resulting in increased stress concentration, a change in the facet contact site and alterations in motion biomechanics [1–3]. These changes lead to degenerative changes in the vertebral segments adjacent to fused vertebrae. This process, referred to as adjacent segment degeneration (ASD), is recognized as one reason for long-term clinical failure after posterior instrumented lumbar fusion. However, little is known about the correlation between the incidence of radiographic findings of ASD and its clinical and functional outcome.

The reported incidence of radiological ASD varies from 5.2 to 49% in various studies [4]. Several risk factors have been proposed for the development of ASD, including increased patient age, female gender, preoperative degenerative changes and instrumentation and length of fusion. However, few studies have prospectively evaluated the involvement of risk factors with the radiological occurrence of ASD [4–10]. Most of the clinical studies have analyzed four or five risk factors, but none of the studies has performed a comprehensive analysis of all of the risk factors for radiographic ASD in a single study.

The purpose of this study was to (1) clarify the role of various risk factors in the development of ASD, (2) compare two instrumentation configuration (facet sparing/abutting) with the development of ASD, (3) correlate the radiological incidence of ASD and its clinical outcome and (4) compare the clinical outcome between patients with radiological evidence of ASD and without ASD.

Materials and methods

Study design

From June 2003 to April 2004, 74 consecutive patients who underwent decompression and instrumented lumbar or lumbosacral fusion at our institution were recruited prior to surgery and were evaluated prospectively over a 5-year period. The inclusion criteria consisted of instrumented fusion, a minimum follow-up period of 5 years, the presence of degenerative lumbar disorders, isthmic spondylolisthesis and preoperative MRI studies. Posterior instrumentation and posterolateral fusion with or without posterior lumbar interbody fusion with cages was used in all of the patients, but with a different proximal connector (facet sparing/abutting). The exclusion criteria in our study included (1) previous surgery at the same level, (2) multilevel fusion with a proximal level above L1 vertebrae, (3) patients on long-term steroid treatment for conditions such as bronchial asthma and organ transplantation, (4) diabetes mellitus (DM), (5) chronic renal failure (CRF) treating with hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, and (6) a nonunion at the fusion site. We enforced the strict extrusion criteria in order to reduce the risks that accompany the use of long term steroids, DM, and CRF, such as the aggravation of functional outcomes after employing various surgical procedures on the lumbar spine. A CT scan was performed to confirm a bony union if there was a suspicious nonunion seen on radiographs. Six patients were lost to follow-up during the study. Ultimately, 68 patients were enrolled in the study. There were 13 men and 55 women and the average patient age at the time of surgery was 63.6 years (age range, 43–78 years). The average duration of follow-up was 67.4 months (range 61–78 months). One senior surgeon performed all the operations and another spine surgeon not involved with the surgeries analyzed the results.

Radiological assessment

All the patients had undergone radiography and MRI of the lumbar spine before surgery to diagnose the degenerative condition and to evaluate the status of an adjacent segment. If any sign of degeneration appeared in an adjacent segment, degeneration was graded as per the classification proposed by Pfirrmann et al. [11] (Table 1). Radiographs included standing anteroposterior and dynamic lateral flexion/extension views. The same radiographs were repeated at 6 months and at yearly intervals until the last follow-up session. The sagittal Cobb angle was measured on lateral radiographs, both from L1 to S1 (total lumbar lordosis) and at the fusion levels. The measurements were made before and at 3 months after surgery. According to the length of fusion, patients were divided in two groups: patients with a short segment (one to two levels) and patients with a long segment (more than three levels). Degenerative changes were considered as ASD when any of the following features were present. (1) Complete collapse of the disc space with endplate sclerosis with or without gas shadow was seen on a lateral radiograph. (2) Sagittal or coronal translation of more than 3 mm was seen. (3) More than a 5° wedging of the disc space was seen on a coronal view (scoliosis). (4) Angular instability of more than 10° on dynamic radiographs was seen. (5) Complete blockage of the spinal canal was seen on MR images [4, 5]. The progression of ASD during the follow-up period and the treatment needed for ASD were evaluated.

Table 1.

Grading of lumbar disc degeneration on T2 weighted sagittal MRI scans by Pfirrmann et al. [11]

| Grade | Structure | Distinction of nucleus and annulus | Signal intensity | Height of intervertebral disc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Homogenous, bright white | Clear | Hyperintense, isointense to cerebrospinal fluid | Normal |

| II | Inhomogenous with or without horizontal bands | Clear | Hyperintense, isointense to cerebrospinal fluid | Normal |

| III | Inhomogenous, Grey | Unclear | Intermediate | Normal to slightly decreased |

| IV | Inhomogenous, grey to black | Lost | Intermediate to hypointense | Normal to moderately decreased |

| V | Inhomogenous, black | Lost | Hypointense | Collapsed disc space |

Clinical and functional outcome

Clinical outcome was assessed using a pain score based on a 10-point VAS (range 1–10). A VAS score of 1 was defined as no pain and a score of 10 was defined as the worst pain imagined by the patient. The patients assessed pain outcome subjectively. Functional outcome was assessed using the ODI questionnaire. The questionnaire was translated into the local language and the questionnaire was self-filled by the patients. The VAS and ODI scores were measured preoperatively, at 6 months postoperatively and then every year until the final follow-up session, along with the evaluations of radiographs.

Patients were divided into two groups according to presence or absence of radiological evidence of ASD. Group 1 patients included patients with radiographic ASD changes. Group 2 patients included patients without radiographic evidence of ASD. Both groups of patients were compared in terms of various risk factors for the development of radiological evidence of ASD including patient age at the time of surgery, gender, history of smoking, preoperative disc degeneration at an adjacent segment and diagnosis, length of fusion, instrumentation configuration, sagittal alignment and type and distal level of fusion. The correlation between the radiological incidence of ASD and its clinical outcome and the clinical outcome between patients with and without radiological evidence of ASD was evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 10.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL USA).

Survival curves were generated by Kaplan–Meier life table analysis and correlation between radiographic ASD and its clinical outcome was analyzed by the Mann–Whitney test and paired t test. Differences between clinical and functional outcome were determined by the use of Mauchly’s test. p values <0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

Of the 68 patients in the study, 14 patients (20.6%) showed radiological signs of degeneration in an adjacent segment and were included as group 1 patients. There were four men and 10 women, and the average patient age at the time of surgery was 63.6 years (age range 50–76 years). The remaining 54 patients did not show any radiographic evidence of ASD until the end of the follow-up period and were included as group 2 patients. There were nine men and 45 women with an average age of 63.4 years (age range 43–78 years).

Relationship between ASD and age

The age of the patients in each group was subdivided based on age ranges including 41–50, 51–60, 61–70 and 71–80 years. For group 1 patients, there was one patient in the 41–50 years range, three patients in the 51–60 years range and five patients in the 61–70 years range and five patients in the 71–80 years range. For group 2 patients, there were five patients in the 41–50 years range, 11 patients in the 51–60 years range, 28 patients in the 61–70 years range and 10 patients in the 71–80 years range. Based on this age distribution, no statistical significant difference was found between either group for ASD (p = 0.624). As the average age of a patient in our study was 63.6 years, patients were subdivided depending on an age more or <64 years at the time of surgery. There were four patients in group 1 and 16 patients in group 2 with an age <64 years. Ten patients in group 1 and 38 patients in group 2 were older than 64 years. Based on this age distribution, no statistical significant difference was found between either group for ASD (p = 0.517).

Relationship between ASD and patient gender

There were four men in group 1 and nine men in group 2 and 10 women in group 1 and 45 women in group 2. There was no significant difference for patient gender for the development of radiological ASD (p = 0.244).

Relationship between ASD and preoperative disc degeneration

Preoperative MRI showed evidence of disc degeneration at adjacent segments in 11 patients. According to the classification described by Pfirrmann et al. [11], four patients had grade II and seven patients had grade III disc degeneration. None of the patients had grade IV or V disc degeneration. Three patients (27.2%) showed progression of degenerative changes during follow-up and were included in group 1. The remaining eight patients in group 2 did not show any sign of progression until the last follow-up session. There was a significant increase in the risk of ASD with the presence of preoperative degeneration at an adjacent segment (p = 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of result of risk factors

| ASD | No ASD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (no. of patients) | 0.517 | ||

| <64 years | 4 | 16 | |

| >64 years | 10 | 38 | |

| Gender | 0.244 | ||

| Male | 4 | 9 | |

| Female | 10 | 45 | |

| Pre op diagnosis | 0.088 | ||

| Stenosis | 6 | 20 | |

| Scoliosis | 7 | 15 | |

| SPL | 1 | 19 | |

| Pre op degeneration | 3 | 8 | 0.001 |

| Grade II | 1 | 3 | |

| Grade III | 2 | 5 | |

| Length of fusion | 0.119 | ||

| Short (1–2 level) | 8 | 42 | |

| Long (>3 level) | 6 | 12 | |

| Type of fusion | 0.100 | ||

| PLF | 5 | 29 | |

| PLIF | 2 | 14 | |

| Both | 7 | 11 | |

| Configuration of instrumentation | 0.946 | ||

| Facet sparing | 10 | 38 | |

| Facet abutting | 4 | 16 | |

| Distal level of fusion | 0.453 | ||

| L5 | 10 | 33 | |

| S1 | 4 | 21 | |

Relationship between ASD and the length of fusion

Eight patients (57.1%) in group 1 and 42 patients (77.8%) in group 2 were operated with a short segment fusion. A long segment fusion was performed in six patients (42.9%) in group 1 and in 12 patients(22.2%) in group 2. No statistically significant difference was noted between a short and long segment fusion (p = 0.119).

Relationship between ASD and the preoperative diagnosis

In group 1, six patients were diagnosed as having stenosis, seven patients were diagnosed as having degenerative scoliosis and one patient was diagnosed as having degenerative spondylolisthesis preoperatively. In group 2, 20 patients were diagnosed as having stenosis, 14 patients were diagnosed as having degenerative scoliosis, nine patients were diagnosed as having degenerative spondylolisthesis and 11 patients were diagnosed as having isthmic spondylolisthesis. However, no statistically significance was found between the preoperative diagnosis and the incidence of ASD (p = 0.088).

Relationship between ASD and instrumentation configuration

Two instrumentation configurations were mainly used: facet sparing with an offset connector and facet abutting. For group 1, four patients (28.6%) were operated with facet sparing and 10 patients (71.4%) were operated with a facet abutting instrumentation system. In group 2, 38 patients (70.4%) were operated with facet sparing and 16 patients (29.6%) were operated with a facet abutting instrumentation system. Instrumentation configuration did not show a significant difference for causation of radiographic ASD (p = 0.946).

Relationship between ASD and the fusion technique

In group 1, posterolateral fusion (PLF) was used in five patients (35.7%), posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) was used in two patients (14.3%) and both PLF and PLIF were used in seven patients (50%). In group 2, PLF was used in 29 patients (53.7%), PLIF was used in 14 patients (25.9%) and combined PLF and PLIF were used in 11 patients (20.3%). The incidence of ASD was not significantly different for the use of the different fusion methods (p = 0.100).

Relationship between ASD and distal fusion level

According to the distal fusion level, patients were divided as lumbar (floating) or lumbosacral (non-floating) fusion. Ten patients (71.4%) in group 1 and 33 patients (61.1%) in group 2 had lumbar fusion. Four patients (28.6%) in group 1 and 21 patients (38.9%) in group 3 had lumbosacral fusion. No statistical significance difference was noted for either fusion type (p = 0.453).

Relationship between ASD and sagittal alignment

The results for sagittal alignment through L1–S1 (total lumbar lordosis) and the fusion level are summarized in Table 3. Patients in group 1 had low mean total lumbar lordosis both preoperatively (33.4°) and post-operatively (37.0°) as compared to group 2 patients (42.1° and 43.2°, respectively). Although this difference in sagittal alignment was not statistically significant, there was a definite trend toward less lumbar lordosis in group 1 patients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Statistical results for sagittal alignment

| ASD group | No ASD group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1–S1 lordosis | |||

| Pre op | 33.42 ± 11.65 | 42.14 ± 15.67 | 0.059 |

| Post op | 37.00 ± 6.67 | 43.24 ± 13.68 | 0.082 |

| Fused level lordosis | |||

| Pre op | 18.90 ± 11.61 | 18.56 ± 10.91 | 0.776 |

| Post op | 20.47 ± 10.21 | 19.76 ± 8.90 | 0.922 |

Summary of ASD changes

In group 1 patients, degeneration of an adjacent segment occurred most commonly proximal to prior fusion (71.4%, 10/14), although degeneration of an adjacent segment occurred distally and both distally and proximally in a minority of patients (21.4%, 3/14 and 7.1%, 1/14), respectively. The average duration of development of ASD from surgery was 28.7 months (range 12–60 months). All 14 patients had radiographic signs of degeneration and were thus assigned to group 1. Only three patients (21.4%) had clinical signs and symptoms of degeneration.

Revision procedures

Three patients required revision procedures for adjacent segment disease. One patient had retrolisthesis (instability in extension) and two patients had stenosis with complete collapse of intervertebral disc space. A revision procedure was performed at 36 months in the patient with retrolishtesis and a revision procedure was performed at 12 and 32 months (Fig. 1), respectively, in the two patients with stenosis after primary surgery. In all three patients, wide decompression and extension of fusion with instrumentation was performed. The revision cases were included in the study and were subjected to follow-up until 5 years after primary surgery.

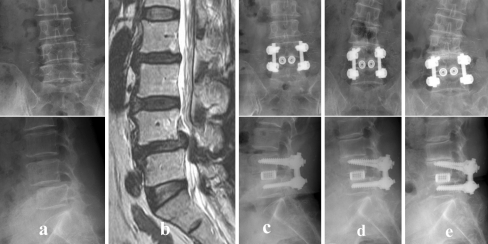

Fig. 1.

a, b A 72-year old woman with L4–5 degenerative spondylolisthesis (ODI score, 76; VAS score, 9) underwent L4–5 PLIF. c No ASD changes are seen at the first year follow-up (ODI score, 38; VAS score, 5). d Three year follow-up shows initiation of ASD changes (decreased disc space) (ODI score, 62; VAS score, 8). e Although a radiograph obtained at 5-year follow-up shows complete collapse with end plate sclerosis and coronal wedging of the L3–4 disc space, her symptoms were tolerated with 46 of ODI score and 6 of VAS

Clinical and functional outcome

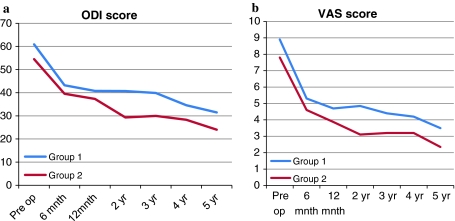

For both groups 1 and 2, the mean ODI and VAS scores were calculated before surgery and at each follow up session. As most radiographic ASD occurs between the second and third year after surgery, the mean ODI and VAS scores of both groups were compared preoperatively and at 2 and 3 years postoperatively, and the difference between the ODI and VAS scores between both groups was calculated at the same time. There was a significant decrease in the ODI and VAS scores at both the 2- and 3-year follow-up sessions as compared to the preoperative scores for both groups 1 and 2 (Fig. 2). In addition, there was a significant difference of VAS scores between groups 1 and 2 at the 2-year follow-up session after surgery (p = 0.045) (Table 4; Fig. 3).

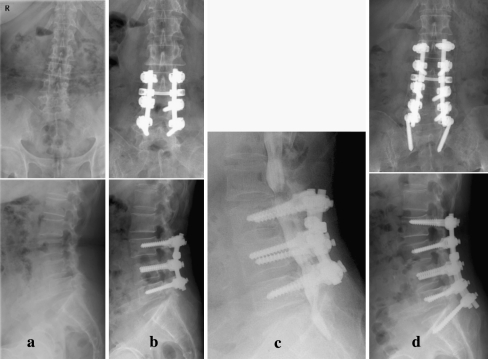

Fig. 2.

a, b A 68 year old female with degenerative scoliosis and L3–4, L4–5 stenosis underwent L3–4, L4–5 decompression and PLF. c At 32 months after primary surgery, the patient developed proximal and distal level stenosis. d Revision surgery was performed with extension of decompression and fusion with instrumentation

Table 4.

Adjacent segment degeneration

| Sr No. | Proximal/distal | F/up duration | Onset of ASD radiographic finding | Last f/up additional findings | Revision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pr | 24 | Traction spur | Endplate sclerosis, disc collapse | |

| 2 | Pr | 24 | Retrolisthesis | Angular instability | |

| 3 | Pr | 24 | Retrolisthesis | Endplate sclerosis | |

| 4 | Pr | 60 | Coronal disc wedging | Traction spur | |

| 5 | Pr | 48 | Retrolisthesis | Decrease disc space | |

| 6 | Di | 36 | Retrolisthesis | End plate sclerosis | |

| 7 | Pr | 12 | Traction spur | Decrease disc space | |

| 8 | Pr | 36 | Traction spur | Coronal wedging of disc space | |

| 9 | Pr + Di | 32 | Stenosis | Decrease disc space | + |

| 10 | Pr | 22 | Anterolisthesis | Angular instability | |

| 11 | Di | 24 | Angular instability | Retrolisthesis | |

| 12 | Pr | 12 | Stenosis | End plate sclerosis | + |

| 13 | Pr | 12 | Retrolisthesis | Disc collapse | |

| 14 | Di | 36 | Retrolisthesis | Disc collapse | + |

Pr Proximal, Di distal, F/up follow-up

Fig. 3.

A comparison between the ODI (a) and VAS (b) scores in group 1 and group 2 is presented

Discussion

There are several reports about adjacent segment degeneration with or without instrumented lumbar or lumbosacral fusion [7, 12–18]. There are convincing biomechanical and clinical data that spinal fusion creates a significant compensatory increase in motion in the adjacent mobile segment by increased stiffness of the fused segment [1, 2, 6, 18–20]. These levels are thought to be subjected to higher loads during normal activities as motion that is normally distributed over many levels is required to occur at fewer levels [1–3]. Ha et al. [1] applied lumbosacral fixation to cadaveric canine spines and an increase in motion and change in facet contact site pattern were noted. Subsequent studies have reported that in vitro biomechanical changes in an adjacent segment occur for an in vivo state as well [21–23]. From a biochemical perspective, Cole et al. [18, 19] investigated adjacent discs in a dog model and found marked changes in disc metabolism and composition after fusion. In vivo animal studies have demonstrated that although various biomechanical and biochemical changes occur in adjacent segments after fusion, clinical implications are contradictory. Many investigators have argued that the radiographic changes seen for ASD are nothing more than normal age related changes [8, 24–26]. In a more recent study by Guigui et al. [7] that compared PLF patients with age and gender-matched controls, significantly higher rates of degeneration next to fused segments were identified. However, most of these studies were retrospective and involved different patient populations and methodologies for ASD. Few studies have attempted to analyze various risk factors for causes of radiological ASD [4, 5, 17]. Few studies have compared the radiological incidence of ASD and its clinical and functional outcome for a long follow-up duration [7, 8].

Many risk factors can lead to progression of ASD. Individual patient characteristics such as age have been shown to be significant risk factors. Aota et al. [5] have observed that the incidence of ASD was much higher in patients with an age greater than 55 years. Several other studies have supported an increased level of ASD with increasing age [9, 24–26]. In our study, the mean age of patients was 63.6 years in group 1 and 63.4 years in group 2. Although the incidence of ASD was higher in patients older than 64 years, this finding was not statistically significant for ASD. We tried to examine gender in risk factor analysis, but we could not find any significance (p = 0.244). In contrast, Park et al. [4] also reported that female gender is a potential risk factor associated with ASD. Ha et al. [27] reported that higher expression of the estrogen receptor might aggravate the degenerative changes in the facet articular cartilage and might also be considered one of the causative factors for the degeneration in postmenopausal women. Therefore, there might be a genetic influence of early degeneration in females than males after instrumented posterolateral lumbar fusion. We also attempted to evaluate smoking as a risk factor for ASD changes. As there were very few cases with a history of smoking (n = 4) as compared to non-smoking cases (n = 64), it was not possible to determine any significance. The addition of instrumentation for fusion can lead to early development to ASD. The immediate rigidity produced by instrumentation caused more stress leading to accelerated degeneration at adjacent levels [24, 28]. With the addition of interbody fusion to instrumented posterolateral fusion, the rigidity of the fused segment increases [25]. However, some studies have shown no change in the incidence of ASD with the use of PLIF as compared to PLF [8, 9]. Similarly, we found no significant correlation between PLF, PLIF or the use of combined procedures (PLF + PLIF) and the incidence of ASD, even though there was a limitation for the number of cases and the number of fused levels. We excluded cases with fusion above L1 vertebrae as the thoracolumbar region has different biomechanical characteristics [29].

Another risk factor related to posterior instrumentation involves placement of the superior pedicle screw. Placement, which depends on the entry site selected, can damage the inferior facet of an adjacent segment [5, 26]. Alterations in facet load-bearing capability from such an injury can potentially contribute to ASD. Chung et al. [30] compared two pedicle screw insertion techniques for facet joint violation in a cadaveric study. These investigators found that superior facet joint violation was more common with the use of the mamillary process technique as compared to the use of the intersection technique. In the present study, all pedicle screws were inserted with the intersection technique and two different instrumentation configurations were used: (1) facet sparing with an offset connector in which the superior screw preserves the facet joint and (2) facet abutting with fixed head screws, which may violate the superior facet joint. In the instrumentation system with the use of an offset connector, the connecting rod is placed away from the superior facet joint to prevent its violation. We compared the radiographic incidence of ASD between the two configurations but could not demonstrate any significant difference, and we have used the intersection technique for screw placement in all patients.

The length of the fusion also plays an important role in the development of ASD, as a longer lever arm produced with multi-segmental fusions causes more stress at the remaining adjacent segments [2, 28, 31, 32]. Moskowitz et al. [33] followed 61 patients for up to 26 years and reported no correlation between back pain and the number of segments fused. Etebar and Cahill [24] showed 78% of patients with ASD had fusions of two or more segments. In contrast, Ghiselli et al. [34] reported that adjacent segment to a single-level fusion had a three times higher risk for the development of ASD than multiple-level fusion. Kumar et al. [8] found no increased risk of ASD with a longer fusion or with the addition of PLIF. We found that the length of fusion was not a significant factor associated with radiographic ASD changes, even though the extended fusion level was limited (L2 to L5–S1). The condition of an adjacent disc has been another factor implicated for ASD. Patients with pre-existing degenerative changes at an adjacent motion segment would have a worse long-term clinical outcome and would experience a higher rate of sequelae [28, 35]. In contrast, Throckmorton et al. [10] found no adverse impact on clinical outcome when lumbar fusion ended adjacent to a degenerative motion segment. Ghiselli et al. [34] found no significant correlation between preexisting radiographic degeneration and ASD. We found that of 11 patients with preoperative evidence of disc degeneration in an adjacent segment (based on MR images), four patients had grade II and seven patients had grade III disc degeneration. However, none of the patients had grade IV or V degeneration prior to surgery [11]. The reason for the lack of grade IV or V degeneration is that segments with grade IV or V degeneration in adjacent segments were included in the primary fusion procedure to prevent subsequent ASD. Among 11 patients, three patients had progressed to grade IV and V degeneration that was diagnosed by postoperative MRI and were included in group 1. Grade IV or V degeneration is a significant risk factor for ASD development, based on our findings.

The role of sagittal alignment for radiographic ASD has been studied by Kumar et al. [9]. These investigators found a significantly high incidence of radiographic ASD with an abnormal C7 plumb line and sacral inclination. Similar results have been reported by Rahm et al. [25] and Djurasovic et al. [36]. For short segment (one to two levels) fusion, the correction of sagittal alignment is less as compared to a long segment (more than three levels). In the present study, 51 patients (75%) underwent short segment fusion and 17 patients (25%) underwent long segment fusion. In addition, none of the fusions was beyond the dorsolumbar region and a level of fusion of more than five levels. Though we could not demonstrate sagittal alignment as a risk factor for the development of ASD, there was a definite non-significant trend toward less total lumbar lordosis prior to index surgery in patients who developed ASD.

There are contradictory data about the prevalence of ASD changes proximal or distal to fusion sites. As determined in a study by Brodsky et al. [12, 13] degenerative changes are equally distributed both above and below the fusion while Cochran et al. [37] found more common posterior translation at adjacent segments below the fusion. However, in both studies, distal ASD was more symptomatic and lead to back pain. Ha et al. [38] considered the sacroiliac joint as a distal joint to the fusion level and reported an increased incidence of degeneration with lumbosacral fusion. In the present study, we found a significant increase in ASD above the level of fusion as compared to below the level of fusion. We also had one case with combined proximal and distal ASD. In the present study, we could not find sacroiliac joint degeneration, as CT scans were not performed. Aota et al. [5] found that 78% of post fusion instability was in the sagittal plane and the most common encountered type was posterior translation. Similarly, our results suggest retrolisthesis is the most common type of radiographic ASD.

Posterior translation of an adjacent segment can lead to narrowing of the intervertebral foramen, impingement of the nerve root and central canal stenosis. Aota et al. [5] found that the average time for the diagnosis of radiographic instability was 25 months after surgery. Etebar and Cahill [24] also observed an average interval of 26.8 months between surgery and the appearance of radiological ASD. In our study, the average time for the onset of radiological ASD was 28.7 months post surgery. Radiographic evidence of ASD does not necessarily correlate with a poor prognosis [33, 39]. Most clinical studies show that functional outcomes are largely unaffected with asymptomatic ASD [5–7, 37, 40]. Kumar et al. [8] examined patients with a long follow-up of 30 years and found that radiographic changes at adjacent levels following lumbar fusion were not accompanied with a significant change in the functional outcomes assessed using validated outcome measures and performance tests. Even though we applied strict inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of patients, the incidence of ASD was not much different from the incidence reported in other studies, and the ASD changes following instrumented fusion were different from age related changes.

There were potential limitations in this study. Further investigation is still required to complete the differentiation criteria between ASD by stress concentration and normal aging related changes, since we notice that the adjacent segments of instrumented spinal fusions themselves, are simultaneously accompanied by some extent of natural aging related changes [9]. We believe, however, our definition of the radiographic evidence for ASD would contribute in certain extent to improve the differentiation criteria between ASD by stress concentration and ASD by normal age related changes.

ODI and VAS scores before surgery and at regular intervals post surgery were determined. As the mean onset of radiographic ASD was 28 months post surgery, we compared the ODI and VAS scores at the second and third year follow-up sessions with the preoperative scores. Even though the radiographs showed evidence of ASD changes, there was a significant decrease in the ODI and VAS scores for both groups 1 and 2 at the follow-up sessions. This finding suggests that there was no correlation between radiographic ASD for groups 1 and 2. In addition, there was a significant difference in the VAS scores between both groups for the second year follow-up. As the ODI and VAS scores had improved at the last follow-up, ASD should be stabilized radiographically over time and if a patient can tolerate pain during the onset of ASD, surgery may not be indicated. This finding confirms our hypothesis that there is no correlation between radiographic development of ASD and its clinical and functional outcome.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Ha KY, Schendel MJ, Lewis JL, Ogilvie JW. Effect of immobilization and configuration on lumbar adjacent-segment biomechanics. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6:99–105. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199304000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagata H, Schendel MJ, Transfeldt EE, Lewis JL. The effects of immobilization of long segments of the spine on the adjacent and distal facet force and lumbosacral motion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1993;18:2471–2479. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199312000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quinnell RC, Stockdale HR. Some experimental observations of the influence of a single lumbar floating fusion on the remaining lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1981;6:263–267. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198105000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park P, Garton HJ, Gala VC, Hoff JT, McGillicuddy JE. Adjacent segment disease after lumbar or lumbosacral fusion: review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:1938–1944. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000137069.88904.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aota Y, Kumano K, Hirabayashi S. Postfusion instability at the adjacent segments after rigid pedicle screw fixation for degenerative lumbar spinal disorders. J Spinal Disord. 1995;8:464–473. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199512000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frymoyer JW, Hanley EN, Jr, Howe J, Kuhlmann D, Matteri RE. A comparison of radiographic findings in fusion and nonfusion patients ten or more years following lumbar disc surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1979;4:435–440. doi: 10.1097/00007632-197909000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guigui P, Wodecki P, Bizot P, Lambert P, Chaumeil G, Deburge A. Long-term influence of associated arthrodesis on adjacent segments in the treatment of lumbar stenosis: a series of 127 cases with 9-year follow-up. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2000;86:546–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar MN, Jacquot F, Hall H. Long-term follow-up of functional outcomes and radiographic changes at adjacent levels following lumbar spine fusion for degenerative disc disease. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:309–313. doi: 10.1007/s005860000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar MN, Baklanov A, Chopin D. Correlation between sagittal plane changes and adjacent segment degeneration following lumbar spine fusion. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:314–319. doi: 10.1007/s005860000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Throckmorton TW, Hilibrand AS, Mencio GA, Hodge A, Spengler DM. The impact of adjacent level disc degeneration on health status outcomes following lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:2546–2550. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000092340.24070.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1873–1878. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200109010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brodsky AE. Post-laminectomy and post-fusion stenosis of the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;115:130–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brodsky AE, Hendricks RL, Khalil MA, Darden BV, Brotzman TT. Segmental (“floating”) lumbar spine fusions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989;14:447–450. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198904000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldner JL. The role of spine fusion. Question 6. Spine. 1981;6:293–303. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198105000-00018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirabayashi K, Maruyama T, Wakano K, Ikeda K, Ishii Y. Postoperative lumbar canal stenosis due to anterior spinal fusion. Keio J Med. 1981;30:133–139. doi: 10.2302/kjm.30.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CK. Accelerated degeneration of the segment adjacent to a lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988;13:375–377. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198803000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheh G, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, Buchowski JM, Daubs MD, Kim Y, Baldus C. Adjacent segment disease followinglumbar/thoracolumbar fusion with pedicle screw instrumentation: a minimum 5-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:2253–2257. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31814b2d8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole TC, Burkhardt D, Ghosh P, Ryan M, Taylor T. Effects of spinal fusion on the proteoglycans of the canine intervertebral disc. J Orthop Res. 1985;3:277–291. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100030304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole TC, Ghosh P, Hannan NJ, Taylor TK, Bellenger CR. The response of the canine intervertebral disc to immobilization produced by spinal arthrodesis is dependent on constitutional factors. J Orthop Res. 1987;5:337–347. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100050305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee CK, Langrana NA. Lumbosacral spinal fusion. A biomechanical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1984;9:574–581. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198409000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Axelsson P, Johnsson R, Stromqvist B. The spondylolytic vertebra and its adjacent segment. Mobility measured before and after posterolateral fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:414–417. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199702150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunningham BW, Kotani Y, McNulty PS, Cappuccino A, McAfee PC. The effect of spinal destabilization and instrumentation on lumbar intradiscal pressure: an in vitro biomechanical analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:2655–2663. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199711150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dekutoski MB, Schendel MJ, Ogilvie JW, Olsewski JM, Wallace LJ, Lewis JL. Comparison of in vivo and in vitro adjacent segment motion after lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:1745–1751. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199408000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Etebar S, Cahill DW. Risk factors for adjacent-segment failure following lumbar fixation with rigid instrumentation for degenerative instability. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:163–169. doi: 10.3171/spi.1999.90.2.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahm MD, Hall BB. Adjacent-segment degeneration after lumbar fusion with instrumentation: a retrospective study. J Spinal Disord. 1996;9:392–400. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199610000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiltse LL, Radecki SE, Biel HM, DiMartino PP, Oas RA, Farjalla G, Ravessoud FA, Wohletz C. Comparative study of the incidence and severity of degenerative change in the transition zones after instrumented versus noninstrumented fusions of the lumbar spine. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12:27–33. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199902000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ha KY, Chang CH, Kim KW, Kim YS, Na KH, Lee JS. Expression of estrogen receptor of the facet joints in degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:562–566. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000154674.16708.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu K, Zucherman J, White A. The long term effect of lumbar spine fusion: Deterioration of adjacent motion segments. In: Yonenobu K, Ono K, Takemitsu Y, editors. Lumbar Fusion and Stabilization. Tokyo: Springer; 1993. pp. 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panjabi MM, White AA., 3rd Basic biomechanics of the spine. Neurosurgery. 1980;7:76–93. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198007000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung KJ, Suh SW, Swapnil K, Yang JH, Song HR. Facet joint violation during pedicle screw insertion: a cadaveric study of the adult lumbosacral spine comparing the two pedicle screw insertion techniques. Int Orthop. 2007;31:653–656. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0249-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen WJ, Lai PL, Niu CC, Chen LH, Fu TS, Wong CB. Surgical treatment of adjacent instability after lumbar spine fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:E519–E524. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200111150-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chow DH, Luk KD, Evans JH, Leong JC. Effects of short anterior lumbar interbody fusion on biomechanics of neighboring unfused segments. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21:549–555. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199603010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moskowitz A, Moe JH, Winter RB, Binner H. Long-term follow-up of scoliosis fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:364–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghiselli G, Wang JC, Bhatia NN, Hsu WK, Dawson EG. Adjacent segment degeneration in the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1497–1503. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakai S, Yoshizawa H, Kobayashi S. Long-term follow-up study of posterior lumbar interbody fusion. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12:293–299. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199908000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Djurasovic MO, Carreon LY, Glassman SD, Dimar JR, 2nd, Puno RM, Johnson JR. Sagittal alignment as a risk factor for adjacent level degeneration: a case-control study. Orthopedics. 2008;31:546. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20080601-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cochran T, Irstam L, Nachemson A. Long-term anatomic and functional changes in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis treated by Harrington rod fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983;8:576–584. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198309000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ha KY, Lee JS, Kim KW. Degeneration of sacroiliac joint after instrumented lumbar or lumbosacral fusion: a prospective cohort study over five-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:1192–1198. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318170fd35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishihara H, Osada R, Kanamori M, Kawaguchi Y, Ohmori K, Kimura T, Matsui H, Tsuji H. Minimum 10-year follow-up study of anterior lumbar interbody fusion for isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:91–99. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200104000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyakoshi N, Abe E, Shimada Y, Okuyama K, Suzuki T, Sato K. Outcome of one-level posterior lumbar interbody fusion for spondylolisthesis and postoperative intervertebral disc degeneration adjacent to the fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:1837–1842. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]