Abstract

The transporters associated with antigen processing (TAP) allow the supply of peptides derived from the cytosol to translocate to the endoplasmic reticulum, where they complex with nascent human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I molecules. However, infected and tumor cells with TAP molecules blocked or individuals with nonfunctional TAP complexes are able to present HLA class I ligands generated by TAP-independent processing pathways. These peptides are detected by the CD8+ lymphocyte cellular response. Here, the generation of the overall peptide repertoire associated with four different HLA class I molecules in TAP-deficient cells was studied. Using different protease inhibitors, four different proteolytic specificities were identified. These data demonstrate the different allele-dependent complex processing pathways involved in the generation of the HLA class I peptide repertoire in TAP-deficient cells.

Keywords: Antigen Processing, Flow Cytometry, Immunology, Metalloprotease, Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC), Protease Inhibitor

Introduction

The newly synthesized proteome is sampled continuously by CD8+ lymphocytes as short peptides presented by human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I molecules at the cell surface. The majority of the peptides presented by HLA class I molecules are produced from proteolysis by the proteasome and other cytosolic proteases, such as tripeptidyl peptidase II (1–3), puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase (4), insulin-degrading enzyme (5), thimet oligopeptidase (6), and caspases (7, 8). These peptides are transported into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)2 by TAP, with subsequent N-terminal trimming by the metallo-aminoproteases ERAP1 and 2 frequently being required (9, 10). Peptide binding to nascent HLA class I molecules generates stable peptide-HLA complexes that are exported to the cell membrane where are they exposed to cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocyte recognition (for review, see Ref. 11).

TAP−/− humans (12) and mice (13) have a reduced functional CD8+ population but do not appear to have an increased susceptibility to neoplasms or viral infections. Thus, the TAP-independent pathways may be sufficient to control these diseases and allow individuals with this HLA class I deficiency to live normal life spans with only a limited susceptibility to chronic respiratory bacterial infections. In addition, evidence for TAP-independent pathways of antigen presentation by MHC class I molecules of particular but diverse pathogenic epitopes was reported previously (for review, see Ref. 14–16). The identified proteases involved in the generation of specific ligands in TAP-deficient cells include ER signal peptidase (SPase) (17, 18), ER signal peptide peptidase (SPPase) (19, 20), trans-Golgi network furin (21, 22), and lysosomal cathepsins (23). However, systematic studies of TAP-independent pathways involved in the generation of the overall peptide repertoire associated with different HLA class I molecules have not been reported. Studying the reexpression of newly synthesized complexes of different HLA class I molecules in the presence of diverse protease inhibitors allowed the determination of several allele-dependent processing pathways in TAP-deficient cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines

T2 is a TAP-deficient human cell line that express HLA-A2, -B51, and -Cw1 class I molecules on the cell surface (24). T2-B27 cells were generated by transfection of T2 cells with HLA-B27 (a gift from Dr. David Yu, University of California, Los Angeles). T2 and T2-B27 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Chemicals

Brefeldin A (BFA), chloroquine (CQ), and all protease inhibitors were from Sigma-Aldrich except leupeptin (Amersham Biosciences), pepstatin (Roche Applied Science), butabindide (Tocris), decanoyl-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-CMK (dec-RVKR) (Bachem), (z-LL)2 ketone (Merck), and lactacystin (Dr. E. J. Corey, Harvard University). The general specificity and activity of all inhibitors used in this study are summarized in Table 1. The normal HLA class I re-expression of at least one allele for each inhibitor demonstrates no toxic effect by the use of different inhibitors (see below).

TABLE 1.

General specificity of inhibitors used in this study

| Inhibitor | Abbreviation | Specificity | Reference | Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brefeldin A | BFA | Vesicle transport | 30, 31 | 5 μg/ml |

| Lactacystin | LC | Proteasome chymotryptic and tryptic activities | 32–34 | 10 μm |

| Epoxomicin | EPOX | Proteasome chymotrypsin-like activity | 35, 36 | 1 μm |

| E64 | E64 | Cysteine proteases C1 | 39 | 100 μm |

| Leupeptin | LEU | Trypsin-like proteases and cysteine proteases | 37 | 100 μm |

| Pepstatin | PEPST | Aspartic proteases | 37, 38 | 100 μm |

| 1,10-Phenanthroline | PHE | Metalloproteases and caspase-1 | 38, 40 | 50 μm |

| Leucinthiol | LeuSH | Metallo-aminopeptidases including ERAAP | 43 | 30 μm |

| Butabindide | BUT | Tripeptidyl peptidase II | 56 | 100 μm |

| Puromycin | PUR | Dipeptidyl-peptidase II and puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase | 57 | 0.5 μg/ml |

| Decanoyl-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-CMK | dec-RVKR | Furin and other members of the SPC family | 58 | 100 μm |

| (z-LL)2 ketone | z-LL2 | Signal peptide peptidase | 19, 20 | 100 μm |

| Chloroquine | CQ | Lysosomotropic agent | 47, 48 | 50 μm |

Acid Stripping and HLA Class I Reexpression

Cells were washed with RPMI 1640 medium in the absence of serum and incubated for 90 s with ice-cool acid-stripping medium (0.3 m glycine HCl and 1% BSA in water, pH 2.4) as reported previously (25). Culture medium was added to neutralize the pH. Cells were washed three times, resuspended in assay medium (RPMI 1640 medium with 1% BSA) at 106/ml, and incubated at 37 °C for 6 h in the presence or absence of inhibitors at the indicated concentrations (Table 1). Serum-free conditions were used throughout.

Flow Cytometry

HLA expression levels were measured using the monoclonal antibodies (Abs) ME1 (anti-HLA-B27) (26) in T2-B27 cells; polyclonal H00003106-B01P (specific for HLA-B class I molecules; Abnova) in T2 cells; and monoclonal PA2.1 (anti-HLA-A2) (27) and polyclonal SC-19438 (specific for HLA-C class I molecules; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in T2 and T2-B27 cells simultaneously as described previously (28). Samples (104 cells) were run on a FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using CellQuest Pro 2.0 software (BD Biosciences). Percentage of inhibition of HLA reexpression obtained by the addition of the indicated inhibitors (Table 1) was calculated utilizing the following equation.

|

Statistical Analysis

To analyze statistical significance, an unpaired Student's t test was used. p values < 0.01 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Endogenous Processing of TAP-independent HLA Ligands

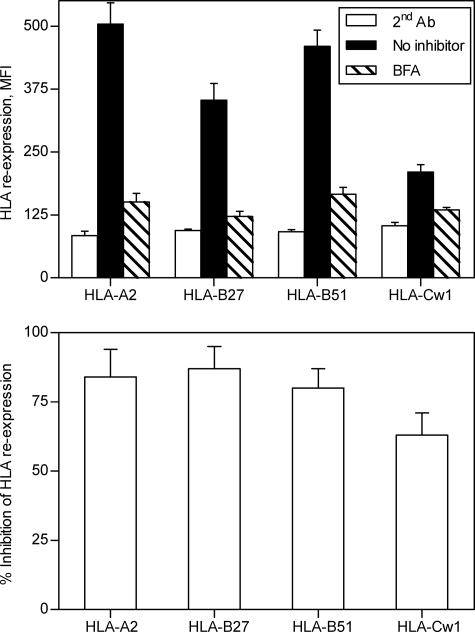

To examine the generation of the TAP-independent HLA-bound peptide repertoire, TAP-deficient T2 and T2-B27 cells, treated with acid to remove surface class I peptide complexes, were allowed to reexpress newly synthesized complexes for 6 h. The T2-B27 cell line was selected because it expresses one each of the endogenous HLA-A, -B, and -C alleles and an additional HLA-B class I molecule, thus mimicking a partial heterozygous haplotype. This expression pattern allows four different class I molecules to be studied. As reported previously for some MHC class I alleles (29), different reexpression levels were found in each of the four HLA class I molecules studied (Fig. 1, upper). To test whether TAP-independent ligands require endogenous processing, HLA reexpression was analyzed in the presence of BFA. This drug blocks class I export beyond the cis-Golgi compartment (30, 31), preventing the surface expression of newly assembled class I-peptide complexes from endogenous origin. The reexpression level of all four HLA class I alleles expressed by the TAP-deficient cells used was decreased significantly: 84% ± 10% for HLA-A2, 87% ± 8% for HLA-B27, 80% ± 7% for HLA-B51, and 63% ± 8% for HLA-Cw1 (Fig. 1). These results demonstrated that the generation of the TAP-independent HLA-ligands was generated primarily from proteins endogenously processed in TAP-deficient cells.

FIGURE 1.

Surface reexpression of HLA class I molecules after acid stripping in the presence of BFA. T2 and T2-B27 cells were untreated (black bars) or incubated with 5 μg/ml BFA for 6 h (hatched bars) after acid washing. Stability at the cell surface of HLA-A2, -B27, -B51, and -Cw1 class I molecules of the TAP-deficient cells was measured by flow cytometry using monoclonal Ab ME1 (anti-HLA-B27) in T2-B27 cells; polyclonal H00003106-B01P (specific for HLA-B class I molecules) in T2 cells; and monoclonal Abs PA2.1 (anti-HLA-A2) and polyclonal SC-19438 (specific for HLA-C class I molecules) in T2 and T2-B27 cells simultaneously. The data are expressed as MFI ± S.D. (error bars) (upper) or percentage of inhibition ± S.D. (lower) of HLA surface reexpression in presence of BFA and are the means of three or four different experiments.

Proteasome Inhibitors Differentially Affect the TAP-independent Expression of Distinct HLA Class I Molecules

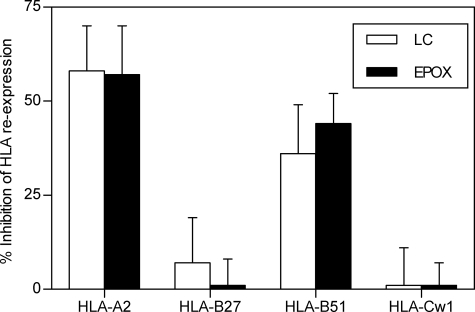

To study the involvement of different proteolytic activities in the generation of TAP-independent ligands presented by HLA class I molecules, the surface reexpression of different HLA class I molecules after acid stripping in T2-B27 TAP-deficient cells was performed in the presence or absence of different inhibitors. Previously, partial block (∼50% of inhibition) of HLA-A2 reexpression in TAP-deficient cells caused by the addition of lactacystin, a Streptomyces metabolite (32–34) (Table 2), demonstrated a role for proteasomes in HLA class I processing of TAP-independent HLA-A2 ligands (25). The involvement of multicatalytic complex proteasome in the processing of ligands presented by other HLA class I was studied. Both lactacystin and epoxomicin (35, 36), another proteasome inhibitor, partially block both HLA-A2 and -B51 reexpression (Fig. 2), implicating the proteasomes in the generation of HLA ligands presented by these alleles By contrast, in the same experiment, both proteasome inhibitors have no effect on the reexpression of HLA-B27 and -Cw1 class I molecules. Thus, these data indicate that the proteasome activity is not absolutely required to generate ligands bound to HLA-B27 and -Cw1 class I molecules.

TABLE 2.

Summary of inhibition of HLA reexpression

| Alelle | BFAa | LC/EPOX | LeuSH | z-LL2 | CQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-A2 | +b | + | + | + | − |

| HLA-B27 | + | − | + | − | + |

| HLA-B51 | + | + | + | + | − |

| HLA-Cw1 | + | − | − | − | − |

a For specificity of different inhibitors see Table I.

b + and − indicate percentage inhibition >35% and <10%, respectively. All + inhibitions show significant p values (p < 0.01) versus controls without an inhibitor.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of several proteasome inhibitors on surface reexpression of HLA class I molecules after acid washing. T2 and T2-B27 cells as in Fig. 1 were incubated with lactacystin (open bars) or epoxomicin (filled bars) at the indicated concentrations (Table 1) as in Fig. 1. The data are expressed as percentage of inhibition ± S.D. (error bars) as in Fig. 1 and are the means of four or five different experiments.

Metallo-aminopeptidase Inhibitors Specifically Block the TAP-independent Expression of Peptide-HLA-A and -B but Not -C Complexes

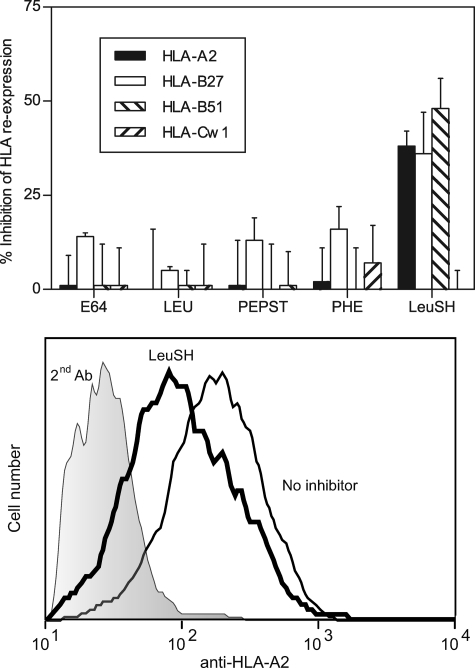

To characterize proteases distinct from proteasomes that may contribute to processing of HLA ligands, experiments with several specific protease inhibitors were performed. Leupeptin (37), pepstatin (37, 38), E64 (39), and 1,10-phenanthroline (38, 40) inhibitors were initially tested because they are specific for different protease families (Table 1) and cover a wide range of protease classes. These four inhibitors had no effect on the HLA reexpression of any of the four alleles studied (Fig. 3). Thus, the enzymes inhibited by these drugs cannot be formally involved in the generation of TAP-independent ligands.

FIGURE 3.

Surface reexpression of HLA class I molecules after acid stripping in the presence of several protease classes inhibitors. Upper, T2 and T2-B27 cells as in Fig. 1 were incubated with the indicated inhibitors at the concentrations summarized in Table 1. HLA-A2 (filled bars), -B27 (open bars), -B51 (right hatched bars), and -Cw1 (left hatched bars) surface reexpression was measured. The data are expressed as percentage of inhibition ± S.D. (error bars) as in Fig. 1 and are the means of three to six different experiments. Lower, a representative experiment with T2 cells stained with anti-HLA-A2 Ab is depicted. The code used is as follows: shaded histogram, second Ab alone (negative control); thin line, no inhibitor; and thick line, 30 μm leucinethiol.

In addition, as the activity of ERAP, an enzyme previously involved in antigen processing (41, 42), is not fully blocked by 1,10-phenanthroline at the concentration used in this study, the inhibitor leucinethiol (Table 2) (43) was used. A partial inhibition of surface reexpression of HLA-A2 (38% ± 4%), -B27 (36% ± 10%), and -B51 (48% ± 8%) but not HLA-Cw1 (0% ± 5%) in TAP-deficient cells treated with leucinethiol was found (Fig. 3). These inhibitions are similar to those reported previously in TAP-sufficient cells, where the surface quantities of the murine MHC class I molecules, Kk and Ld, decreased between 20 and 40% by specific ERAP inhibition (43). Thus, these data implicate ERAP, or other metallo-aminopeptidases, in the generation of a subset of TAP-independent ligands presented by three of four HLA class I molecules examined.

SPPase Is Involved in the Generation of TAP-independent HLA-A2 and -B51 Ligands

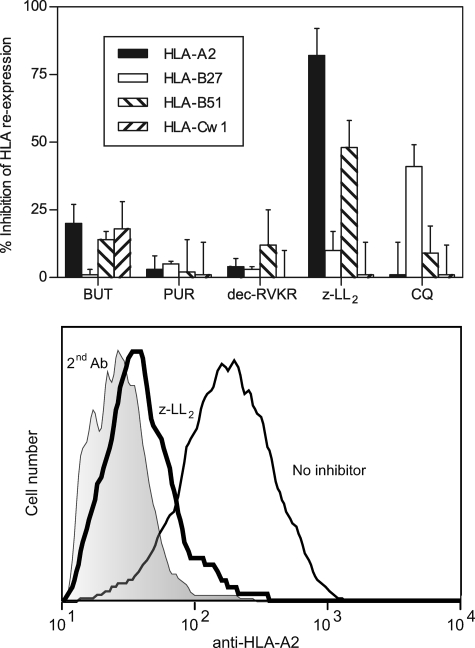

Different proteases such as tripeptidyl peptidase II (1, 2), puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase (4), and furin (21, 22) were previously implicated in antigen processing as being able to generate pathogen-derived peptides. The possible role of these enzymes in endogenous presentation of TAP-independent ligands was studied using available specific inhibitors (Table 1). Inhibition of HLA reexpression was not detected with any of these drugs (Fig. 4) in all HLA class I alleles studied, and thus, the enzymatic activity of these peptidases is not absolutely required in the generation of TAP-independent ligands.

FIGURE 4.

Outcome of different protease-specific inhibitors or a lysosomotropic agent on surface reexpression of HLA class I molecules after acid washing. Upper, T2 and T2-B27 cells as in Fig. 1 were incubated with the indicated drugs at the concentrations summarized in Table 1. HLA-A2 (filled bars), -B27 (open bars), -B51 (right hatched bars), and -Cw1 (left hatched bars) surface reexpression was calculated. The data are expressed as percentage of inhibition ± S.D. (error bars) as in Fig. 1 and are the means of three to six different experiments. Lower, a representative experiment with T2 cells stained with anti-HLA-A2 Ab is depicted. The code used as in follows: shaded histogram, second Ab alone; thin line, no inhibitor; and thick line, 100 μm z-LL2.

Different endogenous TAP-independent HLA-A2 class I ligands are derived by cleavage of the respective signal sequences generated by the SPase complex (16, 44). A specific inhibitor of this enzymatic activity is unavailable; thus, direct involvement of SPase complex in the generation of TAP-independent HLA-A2 ligands could not be studied. However, two SPase-processed peptides need further cleavage by SPPase (19, 20), allowing the hypothetical involvement of SPPase to be examined by treating TAP-deficient cells with the SPPase-specific inhibitor (z-LL)2 ketone (19, 20). This drug specifically inhibits TAP-independent HLA reexpression of HLA-A2 (82% ± 10%), and -B51 (48% ± 10%), but not -B27 (10% ± 7%) or -Cw1 (1% ± 12%). These results demonstrate the role of SPPase in the generation of TAP-independent ligands for some HLA class I molecules.

TAP-independent Expression of Peptide-HLA-B27 Complexes Is CQ-sensitive

Previously, three epitopes processed in an endosomal/lysosomal antigen processing pathway for murine MHC class I presentation in TAP-deficient cells were blocked in cells treated with CQ (23, 45, 46). Thus, the contribution of the CQ-sensitive (47, 48) processing pathway to the generation of overall TAP-independent ligands was evaluated. In our experiments, specific reduction (41% ± 8%) of the HLA-B27 surface levels in presence of CQ was detected (Fig. 4). In contrast, the reexpression of HLA-A2, -B51, and -Cw1 class I molecules was not altered by this drug (Fig. 4). These data indicate that the endosomal/lysosomal antigen processing pathway is HLA class I allele-dependent.

Summary of Inhibitions of HLA Class I Reexpression

With the drugs used in this study (Table 1), three different inhibition patterns of HLA class I expression were found (summarized in Table 2). The inhibition obtained in all HLA-class I alleles examined in presence of BFA indicates that most of the TAP-independent HLA-bound peptides were endogenously processed. The surface levels of HLA-A2 and -B51 class I were dependent on proteasome, metallo-aminopeptidases (probably ERAP), and SPPase activities. Metallo-aminopeptidases and CQ-sensitive processing are relevant for generating HLA-B27 ligands. By contrast, none of the compounds used in this study decreased HLA-Cw1 surface expression.

DISCUSSION

This study was undertaken to compare the generation of the peptide repertoire associated with four different HLA class I molecules in TAP-deficient cells. Previously, the expression of various HLA class I molecules was differentially affected by proteasome inhibitors in TAP-sufficient cells (25). These inhibitors blocked the reexpression of HLA-A2 (60%) and -B51 (80%) class I molecules. In contrast, HLA-B27 was largely insensitive to proteasome inhibitors (only 30% of inhibition of reexpression) (25). In the same study, the role of the proteasome in processing TAP-independent HLA-A2 ligands was reported (25). We found that a different MHC class I molecule, HLA-B51, is also proteasome-dependent in the generation of the HLA peptide repertoire in TAP-deficient cells. In addition, the proteasome inhibitors have no effect on the expression of TAP-independent peptide/HLA-B27 or -Cw1 repertoires. Thus, differential involvement of the proteasome in the generation of ligands bound to HLA class I molecules was found in this study. There was a direct correlation of the role of proteasomes in the processing of HLA peptide repertoires of TAP-dependent and -independent ligands between TAP-sufficient and -deficient cells.

The role of SPase in the processing of TAP-independent presented HLA-A2 peptides has been found previously (17, 18, 44). Moreover, SPPase catalyzes intramembrane proteolysis of two signal peptides after they have been cleaved from a preprotein as the signal sequence-derived HLA-E peptides (19, 20). Thus, sequential cleavage by SPase and SPPase was involved in the processing for some peptides. We found that the specific inhibitor for SPPase activity significantly decreased the HLA expression of some alleles in TAP-deficient cells involving these sequential enzymatic activities in the processing of TAP-independent ligands bound to HLA-A2 and -B51 class I molecules.

It is well documented that trimming of ligand precursors in the ER is important for the generation of appropriate peptides for HLA class I binding and that ER-resident aminopeptidase activity has an important impact on the repertoire of ligands presented in TAP-sufficient cells (for review, see Ref. 49). The present study demonstrates that metallo-aminoprotease-sensitive trimming is also required to generate TAP-independent ligands presented by different HLA class I molecules.

HLA-A2 and -B51 class I molecules demonstrated a similar HLA expression inhibition pattern involving the proteasome, SPPase, and metallo-aminopeptidase enzymatic activities in the generation of TAP-independent ligands. Thus, the most likely explanation is summarized via the following model. Multiple endogenous proteins are proteolyzed by the proteasome in the cytosol. Some of the generated peptides are released into the ER as indicated by the presentation in some instances of cytosolic proteins in cells lacking TAP (50, 51). This presentation of peptides could occur by passive diffusion (52), hydrophobic peptides with specific ability to traverse membranes (53), or unidentified transport. In parallel, SPase releases peptides with signal sequence into the ER. Finally, a fraction of total ER-peptides could be processed by SPPase activity and/or ERAP trimming prior to their binding to HLA-A2 or -B51 molecules.

The presentation pathway for extracellular antigens requires endocytosis and degradation in endolysosomal compartments. HLA class II molecules bind the peptides generated, and these complexes are transported to the cell surface (54). Reagents that prevent endosomal acidification block this type of processing, inhibiting the protein cleavage by endosomal enzymes, such as the acidophilic amine CQ. Previously CQ-sensitive endosomal processing of internalized endogenous transmembrane proteins (23) or viral particles (45) for the generation of murine MHC class I-binding peptides was reported. The current study shows the formation of the overall TAP-independent peptide-HLA-B27 complexes by a proteasome-independent but BFA- and CQ-sensitive pathway. These data imply that class I molecules on the cell surface are internalized to an endolysosomal compartment where they intersect with peptides either supplied by the lysosomal polypeptide transporter ABCB9, also named TAP-like (TAPL) (for review, see Ref. 55) or those directly processed by lysosomal proteases. In addition, some of these HLA-B27-restricted peptides need further trimming by metallo-aminopeptidases sensitive to leucinethiol.

In addition, inhibition of the HLA-Cw1 surface expression was not detected with the chemicals used in this study. Thus, the identification of the different peptidase(s) of the antigen processing pathway involved in the generation of HLA-Cw1 ligand awaits further molecular and cellular biology studies.

In summary, different and complex processing pathways involving at least four diverse proteolytic specificities in miscellaneous subcellular locations are required to generate the HLA class I peptide repertoire in TAP-deficient cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs J. A. López de Castro (Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa, Madrid, Spain) and David Yu (University of California, Los Angeles) for cell lines.

This work was supported by Fundación para la Investigación y Prevención del SIDA en España Foundation grants.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- BFA

- brefeldin A

- CQ

- chloroquine

- SPase

- ER signal peptidase

- SPPase

- ER signal peptide peptidase

- TAP

- transporters associated with antigen processing.

REFERENCES

- 1. Seifert U., Marañón C., Shmueli A., Desoutter J. F., Wesoloski L., Janek K., Henklein P., Diescher S., Andrieu M., de la Salle H., Weinschenk T., Schild H., Laderach D., Galy A., Haas G., Kloetzel P. M., Reiss Y., Hosmalin A. (2003) Nat. Immunol. 4, 375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guil S., Rodríguez-Castro M., Aguilar F., Villasevil E. M., Antón L. C., Del Val M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39925–39934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. York I. A., Bhutani N., Zendzian S., Goldberg A. L., Rock K. L. (2006) J. Immunol. 177, 1434–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stoltze L., Schirle M., Schwarz G., Schröter C., Thompson M. W., Hersh L. B., Kalbacher H., Stevanovic S., Rammensee H. G., Schild H. (2000) Nat. Immunol. 1, 413–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parmentier N., Stroobant V., Colau D., de Diesbach P., Morel S., Chapiro J., van Endert P., Van den Eynde B. J. (2010) Nat. Immunol. 11, 449–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kessler J. H., Khan S., Seifert U., Le Gall S., Chow K. M., Paschen A., Bres-Vloemans S. A., de Ru A., van Montfoort N., Franken K. L., Benckhuijsen W. E., Brooks J. M., van Hall T., Ray K., Mulder A., Doxiadis I. I., van Swieten P. F., Overkleeft H. S., Prat A., Tomkinson B., Neefjes J., Kloetzel P. M., Rodgers D. W., Hersh L. B., Drijfhout J. W., van Veelen P. A., Ossendorp F., Melief C. J. (2011) Nat. Immunol. 12, 45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. López D., García-Calvo M., Smith G. L., Del Val M. (2010) J. Immunol. 184, 5193–5199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. López D., Jiménez M., García-Calvo M., Del Val M. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16910–16913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rock K. L., York I. A., Goldberg A. L. (2004) Nat. Immunol. 5, 670–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saveanu L., Carroll O., Lindo V., Del Val M., López D., Lepelletier Y., Greer F., Schomburg L., Fruci D., Niedermann G., van Endert P. M. (2005) Nat. Immunol. 6, 689–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jensen P. E. (2007) Nat. Immunol. 8, 1041–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cerundolo V., de la Salle H. (2006) Semin. Immunol. 18, 330–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Kaer L., Ashton Rickardt P. G., Ploegh H. L., Tonegawa S. (1992) Cell 71, 1205–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Del-Val M., López D. (2002) Mol. Immunol. 39, 235–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johnstone C., Del Val M. (2007) Traffic 8, 1486–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Larsen M. V., Nielsen M., Weinzierl A., L. O. (2006) Curr. Immunol. Rev. 2, 233–245 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wei M. L., Cresswell P. (1992) Nature 356, 443–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Henderson R. A., Michel H., Sakaguchi K., Shabanowitz J., Appella E., Hunt D. F., Engelhard V. H. (1992) Science 255, 1264–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weihofen A., Lemberg M. K., Ploegh H. L., Bogyo M., Martoglio B. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 30951–30956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weihofen A., Binns K., Lemberg M. K., Ashman K., Martoglio B. (2002) Science 296, 2215–2218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gil-Torregrosa B. C., Castaño A. R., López D., Del Val M. (2000) Traffic 1, 641–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gil-Torregrosa B. C., Raúl Castaño A., Del Val M. (1998) J. Exp. Med. 188, 1105–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tiwari N., Garbi N., Reinheckel T., Moldenhauer G., Hämmerling G. J., Momburg F. (2007) J. Immunol. 178, 7932–7942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Salter R. D., Cresswell P. (1986) EMBO J. 5, 943–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Luckey C. J., Marto J. A., Partridge M., Hall E., White F. M., Lippolis J. D., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Engelhard V. H. (2001) J. Immunol. 167, 1212–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ellis S. A., Taylor C., McMichael A. (1982) Hum. Immunol. 5, 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parham P., Bodmer W. F. (1978) Nature 276, 397–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. López D., Samino Y., Koszinowski U. H., Del Val M. (2001) J. Immunol. 167, 4238–4244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Anderson K. S., Alexander J., Wei M., Cresswell P. (1993) J. Immunol. 151, 3407–3419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yewdell J. W., Bennink J. R. (1989) Science 244, 1072–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nuchtern J. G., Bonifacino J. S., Biddison W. E., Klausner R. D. (1989) Nature 339, 223–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fenteany G., Standaert R. F., Lane W. S., Choi S., Corey E. J., Schreiber S. L. (1995) Science 268, 726–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Omura S., Fujimoto T., Otoguro K., Matsuzaki K., Moriguchi R., Tanaka H., Sasaki Y. (1991) J. Antibiot. 44, 113–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee D. H., Goldberg A. L. (1998) Trends Cell Biol. 8, 397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schwarz K., de Giuli R., Schmidtke G., Kostka S., van den Broek M., Kim K. B., Crews C. M., Kraft R., Groettrup M. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 6147–6157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hanada M., Sugawara K., Kaneta K., Toda S., Nishiyama Y., Tomita K., Yamamoto H., Konishi M., Oki T. (1992) J Antibiot. 45, 1746–1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Umezawa H. (1976) Methods Enzymol. 45, 678–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kozlowski S., Corr M., Shirai M., Boyd L. F., Pendleton C. D., Berzofsky J. A., Margulies D. H. (1993) J. Immunol. 151, 4033–4044 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hanada K., Tamai M., Yamagishi M., Ohmura S., Sawada J., Tanaka I. (1978) Agric. Biol. Chem. 42, 523–528 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thornberry N. A. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 244, 615–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saric T., Chang S. C., Hattori A., York I. A., Markant S., Rock K. L., Tsujimoto M., Goldberg A. L. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3, 1169–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. York I. A., Chang S. C., Saric T., Keys J. A., Favreau J. M., Goldberg A. L., Rock K. L. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3, 1177–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Serwold T., Gonzalez F., Kim J., Jacob R., Shastri N. (2002) Nature 419, 480–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weinzierl A. O., Rudolf D., Hillen N., Tenzer S., van Endert P., Schild H., Rammensee H. G., Stevanoviæ S. (2008) Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 1503–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schirmbeck R., Melber K., Reimann J. (1995) Eur. J. Immunol. 25, 1063–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fromm S. V., Duady-Ben Yaakov S., Schechter C., Ehrlich R. (2002) Cell. Immunol. 215, 207–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ziegler H. K., Unanue E. R. (1982) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79, 175–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chesnut R. W., Colon S. M., Grey H. M. (1982) J. Immunol. 129, 2382–2388 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. van Endert P. (2011) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 68, 1553–1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Johnstone C., Guil S., García-Barreno B., López D., Melero J. A., Del Val M. (2008) J. Gen. Virol. 89, 2194–2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Neumeister C., Nanan R., Cornu T., Lüder C., ter Meulen V., Naim H., Niewiesk S. (2001) J. Gen. Virol. 82, 441–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lautscham G., Mayrhofer S., Taylor G., Haigh T., Leese A., Rickinson A., Blake N. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 194, 1053–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lautscham G., Rickinson A., Blake N. (2003) Microbes Infect. 5, 291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. van den Hoorn T., Paul P., Jongsma M. L., Neefjes J. (2011) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 23, 88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bangert I., Tumulka F., Abele R. (2011) Biol. Chem. 392, 61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rose C., Vargas F., Facchinetti P., Bourgeat P., Bambal R. B., Bishop P. B., Chan S. M., Moore A. N., Ganellin C. R., Schwartz J. C. (1996) Nature 380, 403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. McDonald J. K., Reilly T. J., Zeitman B. B., Ellis S. (1968) J. Biol. Chem. 243, 2028–2037 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Contin C., Pitard V., Itai T., Nagata S., Moreau J. F., Déchanet-Merville J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 32801–32809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]