Background: Insulin-stimulated dissociation of PRAS40 from mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 is proposed to promote signaling by enabling increased substrate binding.

Results: PRAS40 release from mTOR complex 1 does promote 4E-BP binding but not mTOR signaling.

Conclusion: Increased substrate binding is the result and not a cause of mTOR complex 1 signaling.

Significance: The mechanism of mTOR activation and the functions of PRAS40 phosphorylation remain to be defined.

Keywords: Akt PKB, Amino Acid, Enzyme Mechanisms, Insulin, mTOR, mTOR Complex (mTORC), 4E-BP, PRAS40, Rheb

Abstract

Insulin activation of mTOR complex 1 is accompanied by enhanced binding of substrates. We examined the mechanism and contribution of this enhancement to insulin activation of mTORC1 signaling in 293E and HeLa cells. In 293E, insulin increased the amount of mTORC1 retrieved by the transiently expressed nonphosphorylatable 4E-BP[5A] to an extent that varied inversely with the amount of PRAS40 bound to mTORC1. RNAi depletion of PRAS40 enhanced 4E-BP[5A] binding to ∼70% the extent of maximal insulin, and PRAS40 RNAi and insulin together did not increase 4E-BP[5A] binding beyond insulin alone, suggesting that removal of PRAS40 from mTORC1 is the predominant mechanism of an insulin-induced increase in substrate access. As regards the role of increased substrate access in mTORC1 signaling, RNAi depletion of PRAS40, although increasing 4E-BP[5A] binding, did not stimulate phosphorylation of endogenous mTORC1 substrates S6K1(Thr389) or 4E-BP (Thr37/Thr46), the latter already ∼70% of maximal in amino acid replete, serum-deprived 293E cells. In HeLa cells, insulin and PRAS40 RNAi also both enhanced the binding of 4E-BP[5A] to raptor but only insulin stimulated S6K1 and 4E-BP phosphorylation. Furthermore, Rheb overexpression in 293E activated mTORC1 signaling completely without causing PRAS40 release. In the presence of Rheb and insulin, PRAS40 release is abolished by Akt inhibition without diminishing mTORC1 signaling. In conclusion, dissociation of PRAS40 from mTORC1 and enhanced mTORC1 substrate binding results from Akt and mTORC1 activation and makes little or no contribution to mTORC1 signaling, which rather is determined by Rheb activation of mTOR catalytic activity, through mechanisms that remain to be fully elucidated.

Introduction

The mammalian target of rapamycin (TOR)2 complex 1 (mTORC1) controls cell size by signaling to the transcriptional apparatus, by regulating the translation of a cohort of mRNAs critical to the enlargement of cell size, and by control of autophagy (1). mTORC1 is composed of three tightly bound polypeptides in a 1:1:1 stoichiometry, i.e. mTOR, raptor, and mLst8 (also known as GβL) (2–4), retrieved largely as a homodimer of this trimer (5). Many other polypeptides can be retrieved with mTORC1 as the stringency of washing is reduced; among the most intriguing is PRAS40 (6–9), a protein first identified as a preferred substrate of insulin-stimulated, Akt-catalyzed phosphorylation (10). PRAS40 is also a substrate of mTORC1 (11–13), however, the physiologic function(s) of PRAS40 and thus of its phosphorylations remains unclear. Perhaps the best characterized direct substrates of mTORC1 are the translational regulatory proteins, S6 kinase 1 and 4E-BP. These bind directly to raptor (14–17), and their association with raptor is crucial to their phosphorylation by mTORC1 in vivo and in vitro. Binding occurs through one or more short motifs on these substrates, the best characterized being the so-called TOS motif (18), which in S6K1 and 4E-BP has the form Phe-Ac-φ-Ac-φ (where Ac = Glu/Asp and φ = Leu/Ile/Met); mutation of Phe in this motif eliminates the ability of 4E-BP or S6K1 to bind raptor and to be phosphorylated in a rapamycin-sensitive manner in cells. The binding of PRAS40 to raptor depends on a variant TOS motif, Phe-Val-Met-Asp-Glu (11). In turn, mTOR-catalyzed phosphorylation strongly promotes the dissociation of these substrates from raptor.

The activity of mTORC1 is controlled by a variety of inputs; insulin and growth factors up-regulate mTORC1 activity, whereas stressors such as hypoxia, energy depletion, glucocorticoids, and TNFα suppress mTORC1 activity (1). This regulation is accomplished primarily or exclusively by regulating the activity of the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC1/TSC2), which is the GTPase activator for the small GTPase Rheb (19). Rheb-GTP is a proximal activator of mTORC1, through its direct binding to the mTOR catalytic domain (20) and by additional mechanisms, such as the generation of phosphatidic acid by Rheb activation of PL-D1 (21) and perhaps by Rheb displacement of the mTOR inhibitor FKBP38 (22). In cells deficient in TSC function, mTORC1 is constitutively active and the impact of these upstream inputs is greatly attenuated or eliminated. By contrast, withdrawal of amino acids (or just leucine) is a potent inhibitor of mTORC1 signaling (23, 24) that does not significantly alter Rheb GTP charging, and whose inhibitory potency is only modestly diminished in TSC-deficient cells (25). Thus, amino acid withdrawal interferes with the ability of Rheb-GTP to bind and activate mTORC1 (26); the inhibitory effect of amino acid withdrawal on mTORC1 can be overcome by overexpression of mutant active forms of the rag GTPases (27, 28), which bind raptor and couple mTORC1 with Rheb (28).

Several observations point to the possibility that the activation of mTORC1 signaling, i.e. mTORC1 kinase activity in vivo, in addition to an activation/disinhibition of the mTOR catalytic domain, involves an enhancement of mTORC1 substrate binding capacity. Early work demonstrated that overexpression of S6K1 inhibited the mTORC1-catalyzed phosphorylation of 4E-BP (29) and more recently, it was shown that mTORC1 substrates S6K1, 4E-BP, and PRAS40 were each mutually competitive in their binding to raptor (6–8, 11–13). RNAi-induced depletion of endogenous PRAS40 has been reported to promote some increase in mTORC1-dependent phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP in serum-deprived cells (6, 7), although impaired mTORC1 signaling after PRAS40 depletion has also been observed (7, 12, 30). The finding that depletion of one mTORC1 substrate enhances the mTORC1-catalyzed phosphorylation of others suggests that even during insulin/nutrient stimulation, the availability of substrate binding sites on endogenous raptor may be limiting for mTORC1-catalyzed substrate phosphorylation. Wang et al. (5) provided the most direct evidence that raptor-mediated substrate binding is regulated, demonstrating that the activation of mTORC1 signaling by insulin treatment of 3T3-L1 adipocytes is accompanied by an increased ability of the extracted mTORC1 complex to bind to the 4E-BP polypeptide in vitro. In the present studies, we sought to characterize the regulation of substrate binding to mTORC1, gain insight into the underlying mechanism, and evaluate the contribution of this alteration to mTORC1 signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

293E cells (kindly provided by Dr Ramnik Xavier) and 293T cells were grown in high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma) and gentamycin (50 mg/ml, Invitrogen) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were plated on 6-cm plates and plasmid constructs were transiently transfected 24 h later using either Lipofectamine, or Lipofectamine 2000 for co-transfection experiments involving both plasmids and siRNA oligos according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). For all treatments (48 h post-transfection) 293E cells were initially serum starved in DMEM for 16 h, for insulin stimulation fresh DMEM was added for 1 h, then fresh DMEM was added again for a further 30 min in the presence or absence of 1 μm insulin (Sigma). For amino acid starvation, DPBS (Invitrogen, number 14040) was added for 1 h supplemented with 25 mm glucose (Sigma) and 1 mm sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen), fresh DPBS containing glucose and sodium pyruvate was then added for a further 30 min in the presence or absence of 1 μm insulin. To inhibit mTOR by Torin (31) (a kind gift from N. Gray and D. M. Sabatini) or rapamycin (LC Laboratories), and AKT by Akt inhibitor VIII, isozyme selective, Akti-1/2 (32) (Chemdea), fresh DMEM was supplemented with the appropriate inhibitor for 1 h, fresh DMEM was then added for a further 30 min with the inhibitor in the presence or absence of 1 μm insulin. For 293T cells (40 h post-transfection), fresh DMEM was added supplemented with 1 μm insulin for 30 min or DPBS supplemented with 25 mm glucose, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, and 25 μm LY294002 (Calbiochem) for 2 h. HeLa cells were plated on 6-cm plates and siRNA oligos were transiently transfected 24 h later using Oligofectamine according to the manufacturers instructions (Invitrogen). For co-transfection experiments plasmid constructs were transfected 24 h after siRNA oligos using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturers instructions (Invitrogen). 48 h post-siRNA transfection the medium was replace with DMEM lacking serum; 1 h later fresh DMEM ± insulin (1 μm) was added and the cells were extracted 30 min later. For amino acid starvation, the medium was replaced with DPBS supplemented with glucose and sodium pyruvate for 1 h, followed by fresh DPBS containing glucose and sodium pyruvate for a further 30 min prior to extraction.

GST Pulldowns and Immunoprecipitation

After their respective treatment, cells were washed in PBS and lysed in 500 μl of ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 20 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 5 mm EGTA, 50 mm NaF, 1 mm DTT, protein inhibitor mixture tablet (Roche applied Science), and 0.2% CHAPS or 0.2% Triton X-100) and harvested by scraping, lysates were then spun at 13,200 × g for 10 min at 4 °C in a tabletop centrifuge. For GST pull downs lysates were combined with 30 μl of glutathione-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) and rotated for 1 h and 30 min at 4 °C. GST pulldown assays were washed five times in 500 μl of ice-cold lysis buffer, and then 30 μl of Laemmli buffer was added for immunoblot analysis. For immunoprecipitates, 1 μg of anti-raptor or anti-PRAS40 was coupled to 10 μl of protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare), whereas 1 μg of anti-mTOR was coupled to 10 μl of protein G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) in lysis buffer while rotating for 1 h at 4 °C. FLAG immunoprecipitations used 20 μl of FLAG-agarose (Sigma). Immunoprecipitates were then processed as described for GST pulldown assays.

cDNAs and siRNAs

Expression vectors of eukaryotic GST-tagged proteins (pEBG-4E-BP[5A], pEBG-4E-BP[5A/F114A]), prokaryotic GST-tagged proteins (pGEX-4E-BP and pGEX-P70(355–505)), FLAG-tagged proteins (pCMV5-FLAG-P70, pCMV5-FLAG-Rheb, and pCMV5-Flag-mTOR) and Myc-tagged proteins (pcDNA3-Myc-raptor) were constructed as previously described (2, 11, 14, 20). Due to more robust expression of pcDNA3-Myc-raptor, pcDNA3-Myc-raptor[6A] was generated by cutting a fragment of pRK7-Myc-raptor[6A] (33) (a kind gift from Diane Fingar) using SbfI and FseI. PRAS40 siRNA duplexes with 3′ dTdT overhangs and scrambled controls have previously been described. To generate FLAG-raptor[4A] (S722A, S859A, S863A, S877A), three sequential PCR were performed using mutagenic primers at Ser722 (CGTTCTGTGAGCGCCTATGGAAACATC), Ser859/Ser863 (CTCACTCAGGCGGCCCCCGCCGCCCCCACCAAC), and Ser877 (CAGGCGGGGGGCGCCCCTCCGGCGTCC).

Antibodies

For immunoprecipitation experiments, anti-mTOR, anti-PRAS40 (Pro238), and anti-raptor (R1) were produced by Immuno-Biological Laboratories as previously described (11), whereas anti-FLAG was purchased from Sigma. For Western blotting antibodies were purchased from Sigma (anti-FLAG), Cell Signaling (anti-mTOR, anti-P70-T389, anti-4E-BP, anti-4E-BP-Thr37/Thr46, anti-4E BP-Ser65, anti-4E-BP-Thr70, anti-AKT, anti-AKT-Thr473, anti-GSK3β-Ser9, and anti-Myc), Santa Cruz Biotechnology (anti-P70) and Millipore (anti-PRAS40-Thr246 and anti-GST). Anti-raptor (Arg984), anti-PRAS40 (Pro238), and anti-PRAS40-Ser183 were produced by Immuno-Biological Laboratories as previously described (11). Polyclonal phosphospecific anti-raptor antibodies were produced by immunizing rabbits with the following peptides coupled to KLH: Ser722 (CRSVSpSYGNIamide), Ser863 (CAPApSPTNKGamide), and Ser877 (CQAGGpSPPASamide), where pS represents phosphoserine. Phosphospecific antibodies were purified by initially coupling synthetic peptides (both phospho and nonphospho) to Sulfo-link coupling gel (Thermo Scientific) via an N-terminal cysteine residue. Sera was first passed over the nonphospho column then the phospho column, antibodies were then eluted according to the manufacturers instructions.

Western Blotting

Lysates, GST pulldowns, and immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The membranes were blocked in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) and 5% powdered milk, primary antibodies were then diluted in the same solution and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed in PBST and secondary antibodies (horseradish peroxidase conjugated, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were then added, which were diluted in PBST containing 5% powdered milk for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were finally washed in PBST then analyzed by chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific) using imaging film (Kodak). For multiple analysis membranes were stripped using 1 m NaOH for 10 min at room temperature, followed by three washes in PBS.

Kinase Assay

These were performed essentially as previously described (6) using 0.3% CHAPS or 0.3% Triton X-100 in the lysis and wash buffers. The phosphate transfer reaction used 200 ng of substrate, a final volume of 40 μl, and a 10-min incubation with agitation at 30 °C. Substrates were expressed and purified from Escherichia coli as previously described (20).

Statistical Analysis

Western blots were quantified using Adobe Photoshop. Subsaturating exposures were scanned and for each experiment in a series the scan value of one condition was divided into itself (and thus assigned the invariant value of 1) and into each of the other scan values. To evaluate, in a statistically valid manner, the data from a series of experiments thus normalized, each of the mean ratios was compared with its expected value under the hypothesis of no effect (which is 1), using a one-sample t test. This takes into account that the value of one condition is without variation. The use of normalization is appropriate inasmuch as the absolute scan value is an artifact of the blotting condition and exposure time.

RESULTS

The Binding of GST-4E-BP[5A] to mTORC1 Is Regulated

We sought to devise a probe for the availability of the mTORC1 substrate binding site in intact cells using the well characterized substrate 4E-BP. Inasmuch as the ability of mTORC1 substrates such as 4E-BP and PRAS40 to bind to raptor is strongly inhibited by their phosphorylation, we employed a mutant of 4E-BP wherein all five of the mTORC1-catalyzed phosphorylation sites (Thr37, Thr46, Ser65, Thr70, and Ser83) were substituted with Ala, fused to the carboxyl terminus of GST to make GST-4E-BP[5A]. We showed previously that elimination of these phosphorylation sites enhances the ability of 4E-BP to bind raptor (2); more importantly, the inability of GST-4E-BP[5A] to be phosphorylated renders its association with raptor sensitive only to perturbations of mTORC1 or regulators of substrate binding to mTORC1. The interaction of GST-4E-BP[5A] with raptor is lost by mutation of the 4E-BP TOS motif (Phe114 to Ala), indicating that GST-4E-BP[5A] binds to raptor at the physiologic substrate binding site (Fig. 1A).

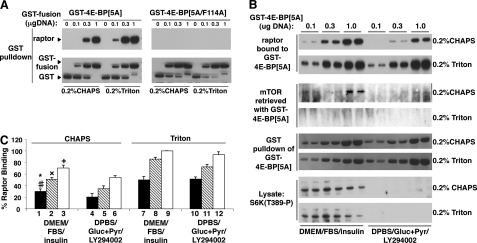

FIGURE 1.

The binding of GST-4E-BP[5A] to raptor is regulated by cell state. A, binding of 4E-BP[5A]or 4E-BP[5Ala/F114A] (F114A inactivates the TOS motif) to raptor in different detergents. 293T cells were co-transfected with GST-tagged 4E-BP[5A]or GST-tagged 4E-BP[5Ala/F114A] with empty vector at varying plasmid quantities. 40 h post-transfection cells were lysed in either CHAPS or Triton lysis buffer and lysates were subjected to a GST pulldown assay. Membranes were analyzed using the anti-raptor and anti-GST antibodies. B, effect of amino acid withdrawal, insulin, and detergent on GST-4E-BP[5A] association with raptor. 293T cells were transfected with varying amounts of GST-tagged 4E-BP[5A]. Forty h later the medium was changed to DMEM/insulin (1 μm)/10% FBS or DPBS/glucose (25 mm)/pyruvate (1 mm)/LY294002 (10 μm). Cells were lysed in a buffer containing either 0.2% CHAPS or 0.2% Triton and lysates were subjected to a GSH-Sepharose pulldown assay. Membranes were analyzed by anti-mTOR, anti-raptor, and anti-S6K-Thr389-P antibodies; GST-4E-BP[5A] was detected by Coomassie Blue staining. C, graphical representation of B, black bars represent 0.1 μg of DNA; hatched bars, 0.3 μg of DNA; and white bars, 1.0 μg of DNA. Mean ± S.E. from three experiments, each performed in replicate. #, p < 0.05, lane 1 versus 4; *, p < 0.01, lane 1 versus 7 and 10; ×, p < 0.01, lane 2 versus 5, 8, and 11; +, p < 0.01, lane 3 versus 6, 9, and 12; lane 7 versus 10, lane 8 versus 11, and lane 9 versus 12 all ns.

In an initial series of experiments, we introduced increasing amounts of cDNA encoding GST-4E-BP[5A] into 293T cells. Two hours prior to extraction, some cells were transferred from complete medium (DMEM + 10% FBS) to DPBS + glucose and pyruvate, followed by the addition of LY294002 30 min prior to extraction; this treatment sought to eliminate both the amino acid and Type 1 PI 3-kinase inputs to mTORC1. The cells were then extracted with either 0.2% CHAPS, which does not disrupt the raptor interaction with mTOR, or with 0.2% Triton X-100, which completely dissociates raptor from mTOR. The recombinant GST-4E-BP[5A] was then retrieved from the extracts with GSH-Sepharose, and the copurified raptor and mTOR were estimated by extracting the beads with SDS sample buffer followed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot. As seen in Fig. 1, B and C, GST-4E-BP[5A] retrieves endogenous raptor in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B, top two panels). Extraction of the cells with Triton X-100, which causes a dissociation of mTOR/hLst8 from raptor (Fig. 1B, compare 3rd and 4th panels from top), increases the amount of raptor recovered at each dose of GST-4E-BP[5A] when compared with CHAPS extraction (Fig. 1B, compare the top two panels), confirming that mTOR itself restricts the ability of GST-4E-BP[5A] to bind raptor. In addition, exposing the cells to amino acid withdrawal plus LY294002 prior to extraction significantly reduces the amount of raptor bound to GST-4E-BP[5A] when the cells are extracted in 0.2% CHAPS, but has little or no effect on raptor recovery when the cells are extracted in Triton X-100 (Fig. 1, B and C). This suggests that the cell state regulates substrate binding to raptor, but primarily when mTOR complex 1 is intact.

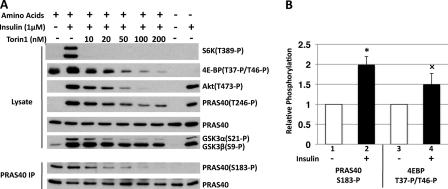

Insulin and Amino Acid Regulation of Akt and mTORC1 Substrate Phosphorylation in 293E Cells

To explore the mechanism(s) underlying the regulation of substrate binding to mTORC1 we turned to the 293E cell line where the activity of the insulin-PI 3-kinase pathway in serum-deprived cells is quite low and is strongly activated by insulin. This is reflected by the absence of detectable phosphorylation of Akt(Ser473) and Akt substrates PRAS40(Thr246) and GSK3β(Ser9) after overnight serum withdrawal, and the robust stimulation of these phosphorylations by insulin (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the level of phosphorylation of 4E-BP(Thr37/Thr46) and PRAS40(Ser183) in serum-deprived 293E cells is ∼70 and 50%, respectively, that seen after insulin stimulation (Fig. 2B); these high basal phosphorylations, which are catalyzed directly by mTORC1, are abolished by a brief withdrawal of medium amino acids (Fig. 2A) and thus reflect the ability of amino acids, independent of insulin, to stimulate mTORC1 activity. The much lower basal phosphorylation of S6K1(Thr389), another direct mTORC1 substrate, appears to reflect the need for a higher level of mTORC1 catalytic activity, as indicated by the much greater sensitivity of S6K1(Thr389) phosphorylation to inhibition by mTOR catalytic inhibitor Torin 1 as compared with the inhibition of 4E-BP(Thr37/Thr46) and PRAS40(Ser183) phosphorylation (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

The effect of insulin, amino acids, and Torin1 on mTOR signaling in 293E cells. A, 293E cells serum starved overnight were stimulated with insulin in the presence or absence of varying concentrations of Torin1; some cells were transferred to DPBS 1 h prior to insulin stimulation. Cells were lysed in a lysis buffer containing 0.2% CHAPS and aliquots were subjected to PRAS40 immunoprecipitation. After SDS-PAGE and electroblot, membranes were analyzed by anti-S6K-Thr389-P, anti-4EBP1-Thr37-P/Thr46-P, anti-AKT-Thr473-P, anti-PRAS40-Thr246-P, anti-PRAS40, anti-GSK3β-Ser9-P, and anti-PRAS40-Ser183-P antibodies. B, graphical representation of the effect of insulin on PRAS40-Ser183 and 4E-BP-Thr37/Thr46 phosphorylation. White bars, serum starvation; black bars, insulin. Mean ± 1 S.D. of three experiments. *, p < 0.01, lane 1 versus 2; ×, p < 0.05, lane 3 versus 4.

Insulin Enhances the Binding of GST-4E-BP[5A] to mTORC1 in an Amino Acid-dependent Manner in 293E Cells

As in 293T cells, extraction of serum-deprived 293E cells with Triton X-100 results in a much greater recovery of endogenous raptor with transiently expressed GST-4E-BP[5A] than does extraction in CHAPS (Fig. 3A). Extraction in Triton X-100, i.e. removal of mTOR from raptor, does not itself alter the amount of PRAS40 bound to raptor as shown by the raptor immunoprecipitate (Fig. 3C, third panel from top), so that the Triton X-100-induced increase in GST-4E-BP[5A] binding to raptor is not attributable to the displacement of PRAS40, consistent with the view that mTOR itself restricts access of GST-4E-BP[5A] to raptor. Insulin promotes the robust activation of Akt and phosphorylation of its substrates PRAS40(Thr246) and GSK3β(Ser9) (Fig. 2A), accompanied by a substantial increase in the binding of endogenous mTORC1 to GST-4E-BP[5A] in the CHAPS extract (Fig. 3, A and B). Despite the much higher basal level of raptor binding to GST-4E-BP[5A] in the Triton extract, insulin treatment may cause a further increase in the binding of GST-4E-BP[5A] that, however, is not statistically significant, at least with this number of observations (Fig. 3, A and B). Withdrawal of amino acids prior to the insulin stimulation, which inhibits the ability of insulin to stimulate S6K1(Thr389) phosphorylation, also inhibits insulin stimulated binding of mTORC1 to GST-4E-BP[5A], to a statistically significant extent in the CHAPS extract and possibly in the Triton X-100 extract, although the latter does not achieve statistical significance (Fig. 3, A and B).

FIGURE 3.

The effect of insulin and amino acids on the binding of transiently expressed GST-4E-BP[5A] and endogenous PRAS40 in vivo to endogenous mTORC1 and free raptor. A, the ability of transiently expressed GST-4E-BP[5A] to retrieve endogenous mTORC1 and free raptor from 293E cells. 293E cells were transfected with 1 μg of GST-4E-BP[5A] and stimulated by insulin in DMEM or after incubation in DPBS for 60 min as described under “Materials and Methods.” Cells were extracted in a buffer containing either 0.2% CHAPS or 0.2% Triton and subjected to a GSH-Sepharose pulldown assay. After SDS-PAGE, membranes were analyzed by immunoblot as described in the legend to Fig. 1B. B, graphical representation (mean ± 1 S.D.) of the combined results from three experiments as shown in A; white bars, serum starvation; black bars, insulin; and hatched bars, DPBS. ×, p < 0.02, lane 1 versus 2 and 5; +, p < 0.05, lane 2 versus 3 and 4; *, p < 0.001, lane 2 versus 6; lane 5 versus 6–8, all non-significant. C, the effect mTOR removal from mTORC1 on the ability of raptor to bind transiently expressed GST-4E-BP[5A] and endogenous PRAS40. The experiments were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2A except that endogenous raptor was immunoprecipitated. D, the effect of insulin and amino acid withdrawal on the binding of endogenous PRAS40 to endogenous raptor. The experiments were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2A except that endogenous PRAS40 was immunoprecipitated.

mTORC1 Binding of GST-4E-BP[5A] Varies Inversely with the Level of mTORC1-bound PRAS40

Amino acid withdrawal also prevents the ability of insulin to promote PRAS40 release from raptor, as seen both in the raptor (Fig. 3C) and PRAS40 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 3D). The ability of amino acid withdrawal to prevent both PRAS40 release from and increased binding of GST-4E-BP[5A] to mTORC1 occurs without any change in the robust insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of PRAS40(Thr246) but is accompanied by and probably due to the inhibition of PRAS40(Ser183) phosphorylation (Figs. 2A and 3D). The effects of amino acid withdrawal on PRAS40 binding to raptor indicates that insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of PRAS40(Thr246), although necessary for PRAS40 release from raptor in amino acid replete cells (see below), is not per se sufficient, and requires the additional phosphorylation of Ser183, which is catalyzed by mTOR itself.

Depletion of PRAS40 Enhances 4E-BP[5A] Binding to mTORC1 but Does Not Enhance mTORC1 Signaling in 293E and HeLa Cells

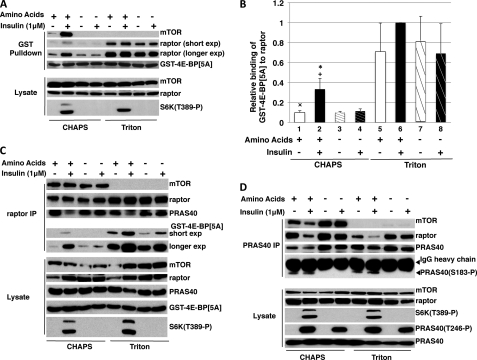

In the experiments shown in Fig. 3, the increase in GST-4E-BP[5A] binding to mTORC1 correlates closely with the extent of PRAS40 dissociation from raptor. We next sought more direct evidence to determine the role of PRAS40 in mTORC1 substrate binding, as well as the extent to which enhanced substrate access contributes to mTORC1 signaling. To examine the extent to which PRAS40 determines access of GST-4E-BP[5A] to mTORC1 we utilized siRNAs to deplete endogenous PRAS40 from 293E cells; moderate overall depletion of PRAS40 was obtained (Fig. 4A). Depletion of endogenous PRAS40 results in a substantial increase in the amount of endogenous mTORC1 recovered with transiently expressed GST-4E-BP[5A] from serum deprived, amino acid-replete cells, to a level ∼2/3 that caused by a maximal dose of insulin (Fig. 4, A and B). This provides direct evidence in support of PRAS40 occupancy of raptor as a major determinant of the ability of GST-4E-BP[5A] to bind to mTORC1. Moreover, the combination of PRAS40 RNAi and insulin yields no greater recovery of raptor with GST-4E-BP[5A] than does insulin alone, consistent with the view that insulin and PRAS40 depletion act to increase substrate access to mTORC1 through the same mechanism.

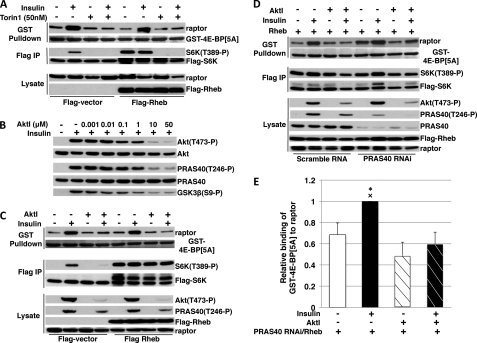

FIGURE 4.

RNAi-induced depletion of PRAS40 from 293E cells increases mTORC1 binding to GST-4E-BP[5A] but not mTORC1 signaling. A, the effect of insulin and PRAS40 RNAi on mTORC1 binding to GST-4E-BP[5A]. 293E cells were co-transfected with 2 μg of GST-4E-BP[5A] and 120 pmol of siRNA (scrambled or PRAS40-directed) and stimulated by insulin in DMEM or ± preincubation with Torin1 (50 nm) as described under “Materials and Methods.” Cells were extracted in a buffer containing 0.2% CHAPS and subjected to a GSH-Sepharose pulldown assay. After SDS-PAGE, membranes were analyzed by immunoblot as described in the legend to Fig. 1B. B, graphical representation of three experiments as described in A (mean ± 1 S.D.) showing the effect of insulin (lanes 1 versus 2 and 5 versus 6) and PRAS40 RNAi (lanes 1 and 2 versus 5 and 6) on GST-4E-BP[5A] binding to intact mTORC1 in 293E cells in DMEM; white bars, serum starved; black bars, insulin; and hatched bars, PRAS40 RNAi. ×, p < 0.001, lane 1 versus 2, 5, and 6; +, p < 0.001, lane 5 versus 2; *, p < 0.01, lane 5 versus 6; lane 2 versus 6, non-significant. C, the effect of RNAi-induced PRAS40 depletion on the phosphorylation of endogenous 4E-BP(Thr37/Thr46) and PRAS40(Ser183) in 293E cells. 293E cells were treated as in A and extracts were analyzed by immunoblot after SDS-PAGE. D, the effect of insulin and PRAS40 RNAi on mTORC1 binding to FLAG-4E-BP1[5A] in HeLa cells. Scrambled or PRAS40-directed RNAi (480 pmol) followed by FLAG-tagged 4E-BP1[5A] (5 μg) were transfected into HeLa cells. After 48 h, cells deprived of serum for 1 h were stimulated by insulin or carrier, extracted in buffer containing 0.2% CHAPS, and subjected to FLAG immunoprecipitation. Immunoblots of the FLAG IP and lysate are shown. Another experiment gave very similar results. E, the effect of RNAi-induced PRAS40 depletion on the phosphorylation of endogenous 4E-BP and S6K in HeLa cells. Forty eight h after introduction of PRAS40 or scramble RNAi, cells were transferred to DMEM without serum or to DPBS + glucose and pyruvate; 1 h later, the DMEM was changed to fresh DMEM (serum starved) or DMEM + insulin (1 μm; insulin) and the DPBS + glucose and pyruvate was replaced with fresh DPBS + glucose and pyruvate (DPBS). Cells were harvested 30 min later and analyzed by immunoblot after SDS-PAGE as shown.

Given the requirement for the amino acid-dependent phosphorylation of PRAS40 (certainly at Ser183 and perhaps other sites, see Refs. 11 and 13) for PRAS40 dissociation from raptor, it is obvious that the PRAS40 release cannot initiate signaling by mTORC1; mTOR catalytic activity must be operative before PRAS40 release can occur. Nevertheless, PRAS40 release may yet be a booster of mTORC1 signaling, because serum-deprived, amino acid-replete 293E cells already exhibit significant TORC1 activity, as indicated by the phosphorylation of PRAS40(Ser183) and 4E-BP(Thr37/Thr46), which are ∼50–70% of their maximal, insulin stimulated level (Fig. 2, A and B). In this circumstance, the insulin activation of Akt-catalyzed PRAS40(Thr246) phosphorylation may be sufficient, together with the amino acid-supported PRAS40(Ser183) phosphorylation, to release PRAS40 from raptor, and so enhance substrate access and mTORC1 signaling. If so, a reduction in PRAS40 sufficient to increase substrate access in serum-deprived, amino acid-replete 293E cells would be expected to increase mTORC1 signaling. Nevertheless, depletion of PRAS40 and enhanced substrate access to mTORC1 to 2/3 the level achieved by a maximal stimulation by insulin does not per se cause stimulation of S6K1(Thr389/Thr412) in serum-deprived, amino acid-replete 293E cells (Fig. 4A), nor does it enhance further the basal phosphorylation of the preferred mTORC1 substrate 4E-BP(Thr37/Thr46) (Fig. 4C). Moreover, RNAi-induced depletion of PRAS40 does not enhance the insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of 4E-BP(Thr37/Thr46) or S6K1(Thr389) (Fig. 4, A and B) (and in some experiments, reduced S6K1 phosphorylation is observed in response to insulin, an effect previously reported, Refs. 7, 12, and 30). Thus the level of PRAS40 binding to raptor is the dominant determinant of the ability of GST-4E-BP[5A] to bind to mTORC1 in cells, however, the substantial increase in substrate access caused by PRAS40 depletion alone is not sufficient to increase mTORC1 signaling in 293E cells. As in 293E cells, RNAi-induced depletion of PRAS40 from HeLa cells enhances mTORC1 binding to 4E-BP[5A] in serum-deprived but not in insulin-stimulated cells (Fig. 4D). Nevertheless, PRAS40 depletion causes little or no change in basal or insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of S6K1 or 4E-BP (Fig. 4, D and E). Clearly, increased substrate binding is not sufficient to increase mTORC1 signaling. Insulin stimulation of mTORC1 signaling must require an increase in mTOR catalytic activity, presumably achieved by Rheb-GTP binding to mTOR.

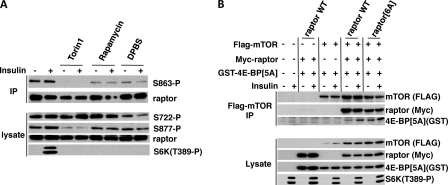

Rheb Overexpression Activates mTORC1 Signaling without Affecting GST-4E-BP[5A] Binding to mTORC1

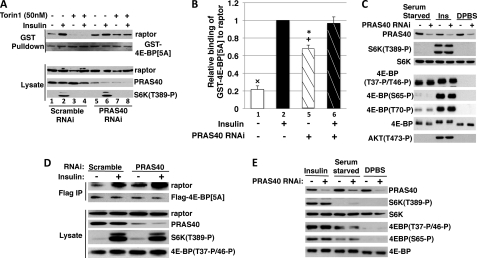

The inability of a substantial increase in substrate access per se to promote mTORC1 signaling at basal levels of mTOR catalytic activity led us to inquire whether an increase in substrate access is required for enhanced mTORC1 signaling. Transiently overexpressed Rheb spontaneously acquires high GTP charging and stimulates mTORC1 signaling independent of any stimulatory input from the PI 3-kinase/Akt or amino acid-regulated elements (20, 26). Rheb overexpression strongly stimulates S6K1(Thr389/Thr412) phosphorylation in serum-deprived 293E cells to an extent that is not further increased by insulin addition (Fig. 5A). Nevertheless, in serum-deprived cells Rheb does not cause a stable increase in the ability of mTORC1 to bind GST-4E-BP[5A], nor does it alter the insulin stimulation of GST-4E-BP[5A] binding to mTORC1. Thus, enhanced substrate access is entirely dispensable for robust mTORC1 signaling to S6K1, its least preferred substrate.

FIGURE 5.

The effect of Rheb ± an AKT inhibitor on GST-4E-BP[5A] binding to endogenous mTORC1 and on mTORC1 signaling. A, recombinant Rheb activates mTORC1 signaling without altering mTORC1 binding of GST-4EBP[5A]. 293E cells were transfected with 1 μg of GST-4E-BP[5A], 500 ng of FLAG-S6K, and 2 μg of FLAG-Rheb or 2 μg of FLAG vector. Cells were serum starved overnight and preincubated ± Torin1 for 1 h, followed by treatment with insulin as described under “Materials and Methods.” Cells were extracted in lysis buffer containing 0.2% CHAPS and aliquots of the extract were subjected to a GSH-Sepharose pulldown and FLAG immunoprecipitation. After SDS-PAGE and blot transfer, membranes were analyzed by immunoblot as shown; GST-4E-BP[5A] was visualized by Coomassie Blue staining. B, the effect of Akt inhibitor VIII, isozyme selective, Akti-1/2 on AKT(Ser473) phosphorylation and Akt signaling in 293E cells. Serum-starved 293E cells were preincubated with the Akt inhibitor at the concentrations shown, then stimulated with insulin. Cells were extracted in a lysis buffer containing 0.2% CHAPS, extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and membranes were analyzed by immunoblot as indicated. C, the Akt inhibitor VIII inhibits the insulin-stimulated binding of GST-4E-BP[5A] to mTORC1 in the presence and absence of recombinant Rheb but does not inhibit Rheb-stimulated mTORC1 signaling. 293E cells were transfected with 1 μg of GST-4E-BP[5A], 500 ng of FLAG-S6K, and 2 μg of FLAG-Rheb or 2 μg of FLAG vector. Cells were preincubated for 1 h ± Akt inhibitor VIII (30 μm) and then treated with or without insulin. Aliquots of cell extracts lysed with 0.2% CHAPS were subjected to GSH-Sepharose pulldown and FLAG immunoprecipitation and processed for immunoblot as described A. D, the component of insulin-stimulated GST-4E-BP[5A] binding to mTORC1 remaining in 293E cells depleted of PRAS40 is suppressed by the Akt inhibitor. 293E cells were co-transfected with 1 μg of FLAG-Rheb, 1 μg of GST-4E-BP[5A], 500 ng of FLAG-S6K, and 145 pmol of scrambled or PRAS40-directed siRNA. Cells were serum starved and preincubated with or without Akt inhibitor VIII (30 μm) for 1 h and then treated with or without insulin. Aliquots of cell extracts lysed with 0.2% CHAPS were subjected to GSH-Sepharose pulldown and FLAG immunoprecipitation and processed for immunoblot as in Fig. 5A. E, graphical representation of the data (mean ± 1 S.D.) from four experiments performed as described for the four right-most lanes of D, showing the effects of Akt inhibitor on the basal and insulin-stimulated binding of mTORC1 to GST-4E-BP[5A] in 293E cells depleted of PRAS40 and expressing recombinant Rheb. White bars, serum starvation; black bars, insulin; hatched bars, AKT inhibitor. ×, p < 0.01, second lane versus first; *, p < 0.001, second lane versus third and fourth; first lane versus third and fourth, non-significant.

Inhibition of Akt in the Presence of Maximal Rheb-GTP Inhibits Insulin Stimulation of GST-4E-BP[5A] Binding to mTORC1 but Not mTORC1 Signaling

We hypothesized that the inability of Rheb overexpression to confer a stable increase in substrate binding is due to a lack of PRAS40(Thr246) phosphorylation and displacement, whereas insulin, through Akt stimulates both Rheb-GTP charging and PRAS40(Thr246) phosphorylation. The ability of Rheb to directly activate mTORC1 and produce a maximal stimulation of S6K1(Thr389/Thr412) phosphorylation in serum-deprived 293E cells, without altering basal or insulin-stimulated substrate binding, enabled us to examine the effect of inhibiting Akt on mTORC1 substrate binding under conditions where Akt actions on TSC and Rheb GTP charging are bypassed. The Akt inhibitor Akti-1/2, which acts by preventing Akt activation (32) (and lacks the ability to inhibit preactivated Akt), causes a dose-dependent inhibition of the insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt(Ser473), PRAS40(Thr246), and GSK3β(Ser9) (Fig. 5B). At 30 μm, Akti-1/2 inhibits the insulin-stimulated increase in the ability of mTORC1 to bind GST-4E-BP[5A], both in the absence and presence of overexpressed Rheb (Fig. 5C). In the presence of insulin and Rheb, the inhibitory effect of Akti-1/2 on mTORC1 substrate binding is evident despite the inability of Akti-1/2 to inhibit Rheb-stimulated phosphorylation of S6K1(Thr389/Thr412). Thus Akt, acting at a site distal to Rheb, is required for insulin stimulation of mTORC1 binding to GST-4EBP1–5A, in part by catalyzing PRAS40(Thr246) phosphorylation and release from raptor. Importantly, however, inhibition of Akt-stimulated access of GST-4E-BP[5A] in the presence of high Rheb-GTP does not reduce mTORC1 signaling.

We inquired whether high-grade depletion of PRAS40 could reduce or eliminate the requirement for Akt in the control of mTORC1 binding of GST-4E-BP[5A]. PRAS40 was depleted with RNAi in the presence of overexpressed Rheb, and the effect of Akti-1/2 on insulin-stimulated binding of mTORC1 to GST-4E-BP[5A] was evaluated (Fig. 5D). As before, substantial overall depletion of PRAS40 in the serum-deprived cells is accompanied by an increase in the binding of mTORC1 to GST-4E-BP[5A], approaching ∼70% of the level seen with maximal insulin stimulation. Despite the extensive RNAi-induced depletion of PRAS40, insulin-stimulated PRAS40(Thr246) phosphorylation at ∼10–20% of the control level remains detectable. The Akti-1/2 inhibitor abolishes this residual PRAS40(Thr246) phosphorylation, and inhibits the residual insulin stimulation of GST-4E-BP[5A] binding to mTORC1. Whether the ability of the Akti-1/2 inhibitor to suppress the residual insulin-stimulated binding of GST-4E-BP[5A] to mTORC1 in the PRAS40-depleted, Rheb-overexpressing cells (Fig. 5E) is due to suppressed phosphorylation of the remaining PRAS40 or to loss of Akt action at some other site is not known.

GST-4E-BP[5A] Binding to mTORC1 Is Not Altered by Raptor P-site Mutations

Several reports have described the phosphorylation of raptor by AMP-activated protein kinase (34), by MAPK/Rsk (35, 36), in response to insulin (33, 37), and in mitosis (39, 40). Whereas AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation of raptor (Ser792) is inhibitory to mTORC1 signaling, the other multiple phosphorylations are reported to promote mTORC1 signaling. Insulin-stimulated sites of raptor phosphorylation consistently reported include Ser863, Ser859, and Ser877. In 3T3-L1 adipocytes, insulin is reported to stimulate the phosphorylation of Ser863 in a rapamycin/wortmannin/amino acid-sensitive manner. Mutation of Ser863 to Ala reduces phosphorylation at Ser859 but not Ser877. The raptor(S863A) mutant is reported to exhibit no alteration in its ability to associate with mTOR or bind 4E-BP in vitro, however, an mTORC1 containing raptor(S863A) is reported to exhibit a modest decrease in insulin-stimulated kinase activity in vitro and in signaling to S6K1 in vivo; mTORC1 containing raptor mutated to Ala at six Ser phosphorylation sites (serine 696, 855, 859, 863, and 877, and Thr706) is reported to show a ∼50% decrease in insulin-stimulated kinase activity in vitro. We sought to determine whether the putative stimulatory phosphorylations of raptor in response to insulin contributed to the ability of insulin to enhance GST-4E-BP[5A] binding to mTORC1. We find that the phosphorylation of endogenous raptor at Ser863, Ser877, and Ser722 is evident in serum-deprived 293E cells and insulin produces little (and in some experiments, no) further stimulation (Fig. 6A). The phosphorylations of Ser863 and Ser877 are consistently inhibited by Torin1 (200 nm), and usually by rapamycin and amino acid withdrawal, consistent with the conclusion that they are catalyzed by mTOR itself within the mTORC1. In 293E cells, we compared the ability of GST-4E-BP[5A] to bind wild type raptor or the raptor mutated to Ala at the six phosphorylation sites indicated above (33). Because substrate binding to free raptor is nonphysiologic, each raptor variant was coexpressed with an excess of recombinant wild type mTOR to ensure that raptor was contained entirely within an mTORC1 assembly. Insulin stimulates the binding of GST-4E-BP[5A] to recombinant mTORC1 containing both wild type or mutant (6 Ala) raptor, and GST-4E-BP[5A] consistently retrieves greater amounts of recombinant mTORC1 containing mutant raptor (Fig. 6B). Thus the loss of these six raptor phosphorylation sites does not impair GST-4E-BP[5A] binding to mTORC1 or its stimulation by insulin.

FIGURE 6.

Mutation of multiple raptor phosphorylation sites does not impair insulin-stimulated binding of GST-4E-BP[5A] to recombinant mTORC1. A, analysis of raptor phosphorylation in 293E cells. 293E cells were serum starved and cells were treated with or without insulin after preincubation with Torin1 (200 nm, 1 h), rapamycin (200 nm,1 h), or DPBS (1 h). Aliquots of extracts were subjected to a raptor IP and the extracts and IPs were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot with anti-raptor, anti-raptor-Ser863-P, anti-raptor-Ser722-P, anti-raptor-Ser877-P, and anti-S6K-Thr389-P antibodies. B, recombinant mTORC1 containing raptor mutant at six phosphorylation sites is unimpaired in its ability to bind GST-4E-BP[5A] in serum-deprived or insulin-stimulated 293E cells. 293E cells were transfected with 1 μg of FLAG-tagged mTOR and/or FLAG vector, 500 ng of Myc-raptor WT or Myc-raptor[6A] and/or Myc vector and 1 μg of GST-tagged 4E-BP[5A] and/or GST vector as indicated. Serum-starved cells were treated with insulin, extracted in a lysis buffer containing 0.2% CHAPS, and subjected to a FLAG immunoprecipitation. The lysates and FLAG immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and the membranes were analyzed using anti-FLAG, anti-Myc, anti-GST, anti-raptor, and anti-S6K-Thr389-P antibodies.

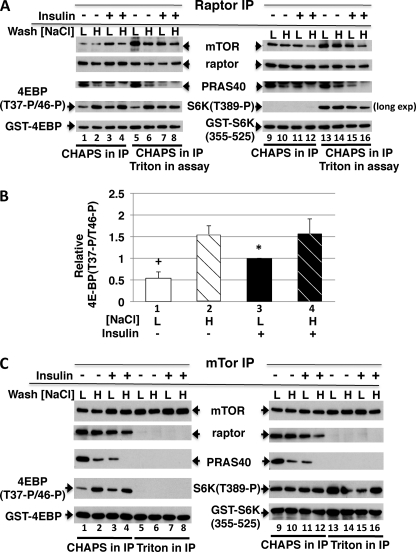

mTORC1 Phosphorylation of 4E-BP in Vitro Reflects Enhanced Access Rather Than mTOR Catalytic Activity

In vitro assay of kinase activity is often used to indicate the activity state of the kinase in vivo. This is generally valid when the kinase has been altered, e.g. by phosphorylation, in a manner that results in a change in its catalytic efficacy that is stable during extraction and immunoprecipitation. In the case of mTORC1, Sancak et al. (6) showed that washing mTORC1 immunoprecipitates with high salt buffers enhances the ability of mTORC1 to phosphorylate 4E-BP in vitro, and eliminates any apparent stimulation of 4E-BP phosphorylation by mTORC1 isolated from insulin-stimulated cells; we confirm this observation (Fig. 7, A and B, fourth panel from top, compare lanes 1 and 3 with 2 and 4). This behavior strongly suggests that the primary basis for the apparent insulin stimulation of the in vitro kinase activity of mTORC1 is an increased ability of mTORC1 to bind the 4E-BP substrate. The same raptor immunoprecipitates can be assayed with a substrate that lacks the TOS motif and thus the ability to bind raptor (GST-S6K(355–525)) (Fig. 7, A and C, lanes 9–16). When the CHAPS-extracted mTORC1 complex in the raptor IP is intact (Fig. 7A, lanes 9–12), no phosphorylation of GST-S6K(355–525) is detectable, illustrating the ability of intact mTORC1 to restrict phosphorylation of nonphysiologic substrates. Addition of Triton to the CHAPS-extracted raptor IP is sufficient to cause a partial dissociation of raptor from mTOR, which enables some GST-S6K(355–525) phosphorylation (Fig. 7A, lanes 13–16); this occurs to a similar extent whether the raptor is immunoprecipitated from serum-deprived or insulin-stimulated cells and washed with 0.15 or 0.4 m NaCl. The pattern of GST-S6K(355–525) phosphorylation after Triton addition to the raptor IP (Fig. 7A, lanes 13–16) indicates that the catalytic efficacy of the mTOR kinase is not detectably altered by the prior insulin treatment, reinforcing the view that the apparent insulin stimulation of mTORC1 activity reflected by 4E-BP phosphorylation in vitro reflects enhanced 4E-BP access rather than the catalytic efficacy of mTOR kinase.

FIGURE 7.

In vitro kinase assay of mTOR and mTORC1. A, the effect of insulin pretreatment and a high salt wash on the ability of a raptor immunoprecipitate to phosphorylate 4E-BP or TOS-less S6K(355–525) fragment in vitro. Serum-deprived 293E cells were treated with or without insulin, extracted in CHAPS-containing buffer, and subjected to a raptor immunoprecipitation. The immunoprecipitates were washed in CHAPS-containing buffer supplemented with 0.15 or 0.4 m NaCl and a kinase assay was performed with or without addition of 1% Triton X-100, using 200 ng of either GST-4EBP (left) or GST-S6K(355–525) (right) as substrate as described under “Materials and Methods.” After SDS-PAGE, the membranes were immunoblotted as indicated. Note that although raptor content is unaltered by addition of Triton, a partial dissociation of raptor from mTOR is achieved by Triton. B, quantitation of the effects of insulin pretreatment and NaCl wash (0.15 m = L, 0.4 m = H) on the ability of the raptor IP to catalyze the phosphorylation of GST-4E-BP in vitro. The results represent four experiments (mean ± 1 S.D.) corresponding to lanes 1–4 in A. +, p < 0.01, lane 1 versus 2–4; *, p < 0.05, lane 3 versus 2 and 4; lane 2 versus 4, non-significant. C, the effect of insulin pretreatment and a high salt wash on the ability of an mTOR immunoprecipitate to phosphorylate 4E-BP or the TOS-less S6K(355–525) fragment in vitro. Serum-deprived 293E cells were treated with or without insulin, extracted in either a CHAPS-containing or a Triton-containing buffer, and subjected to mTOR immunoprecipitation. The immunoprecipitates were washed in the lysis buffer supplemented with 0.15 m (L) or 0.4 m NaCl (H) and a kinase assay was performed using either GST-4E-BP (left) or GST-S6K(355–525) (right) as substrate and analyzed as in A. Note that the pattern of 4E-BP phosphorylation by the mTOR IP extracted in CHAPS corresponds to that of the raptor IP, whereas mTOR extracted in Triton does not phosphorylate GST-4E-BP but avidly phosphorylates GST-S6K(355–525) in an insulin- and NaCl-independent manner.

This conclusion is further supported by assay of an mTOR IP. The mTOR IP prepared from a CHAPS extract contains a mixture of mTORC1, mTORC2, and whatever other mTOR complexes or free mTOR exist. When extracted in Triton, the mTOR IP is devoid of raptor and rictor/sin1. Extracted with CHAPS, the mTOR IP shows an insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of 4E-BP in vitro (Fig. 7C, lanes 1–4), whereas when extracted in Triton, the mTOR IP does not catalyze phosphorylation of 4E-BP, due to the complete dissociation of raptor (Fig. 7C, lanes 5–8). In contrast, phosphorylation of GST-S6K(355–525) by the mTOR IP in vitro is robust and unaffected by insulin, NaCl washing, or mode of extraction (Fig. 7C, lanes 9–16). Phosphorylation of GST-S6K(355–525) by the mTOR IP from CHAPS is likely due to mTORC2 (inasmuch as mTORC1 does not phosphorylate GST-S6K(355–525) at this substrate concentration; Fig. 7A, lanes 9–12). The activity of mTORC2 is certainly stimulated by insulin (as seen by Akt(Ser473) phosphorylation; Fig. 2A) yet this is not reflected by the phosphorylation of GST-S6K(355–525) in vitro. The mTOR IP prepared from Triton contains mTOR from both complexes, and its activity in vitro toward GST-S6K(355–525) also shows no effect of the prior insulin treatment. Thus mTOR kinase assays utilizing 4E-BP do not reflect the catalytic activity of mTOR, the major determinant of signaling in vivo, but rather 4E-BP binding. As shown above (Figs. 3–5), variations in the ability of mTORC1 to bind 4E-BP, at least in response to insulin, is due predominantly to the extent of PRAS40 release, an epiphenomenon of mTOR and Akt activation that makes little or no contribution to mTORC1 signaling in the cell. We therefore view such assays as an unreliable measure of mTORC1 signaling in the cell.

DISCUSSION

Using the ability of a transiently expressed, nonphosphorylatable 4E-BP mutant to retrieve endogenous or recombinant mTOR complex 1, we readily confirm the observation that insulin increases the ability of mTOR complex 1 to bind 4E-BP. We have examined the mechanism responsible for the insulin-induced increase in substrate binding and more importantly, the significance of this phenomenon both to mTOR complex 1 kinase activity as measured in vitro and most importantly, to mTORC1 signaling in vivo. As regards the mechanism for the insulin-induced increase in 4E-BP binding to intact mTORC1, our results indicate that the ability of 4E-BP to bind to mTORC1, both in insulin-stimulated 293E and HeLa cells and in vitro assays of the mTORC1 kinase activity, is determined predominantly by the extent to which mTOR complex 1 has been depleted of PRAS40. Insulin induces the displacement of PRAS40 from raptor through the concurrent dual phosphorylation of PRAS40 at Ser183 (by mTOR) and Thr246 (by Akt); importantly, phosphorylation of PRAS40 at either site alone is not sufficient to displace PRAS40 or to increase substrate binding to mTORC1. Although there are several mTOR-catalyzed sites of phosphorylation on raptor, we find little evidence that phosphorylation of raptor contributes to the insulin-induced increase in binding of 4E-BP to mTORC1; insulin stimulates raptor(Ser863 or Ser877) phosphorylation very modestly (as with 4E-BP(Thr37/Thr46) and PRAS40(Ser183)) and mTOR complexes containing raptor mutants lacking these and several other phosphorylation sites exhibit basal and insulin-stimulated 4E-BP binding that is if anything, somewhat greater than mTORC1 containing wild type mTORC1 raptor.

Our most important conclusion, however, is that the insulin-induced changes in the PRAS40 content of mTORC1 and mTORC1 substrate binding (measured as described above) are not important drivers or determinants of mTORC1 signaling in vivo, but rather are a result of mTORC1 activation when it occurs concomitant with the activation of the Akt kinases. In other words, insulin enhanced substrate access in serum-deprived 293E cells, where basal mTORC1 activity toward 4E-BP(Thr37/Thr46) and PRAS40(Ser183) is already substantial, is an effect predominantly of Akt activation and not causal to mTORC1 activation, or sufficient per se to boost mTORC1 signaling. Thus, RNAi-induced depletion of PRAS40, although capable of increasing the association of GST-4E-BP[5A] to mTORC1 in vivo to about 70% of the extent of insulin does not cause increased signaling of mTORC1 to S6 kinase 1 or 4E-BP in 293E or in HeLa cells. Nor is increased substrate access necessary for Rheb-induced stimulation of mTORC1 signaling; Rheb overexpression, although strongly activating mTORC1 signaling in 293E cells, does not increase the binding of GST-4E-BP[5A] to mTORC1. Whereas Rheb strongly promotes PRAS40(Ser183) phosphorylation, Rheb does not alter PRAS40(Thr246) phosphorylation and therefore does not cause the displacement of PRAS40 from mTORC1; 4E-BP binding is thus not altered, whereas signaling (to S6K1) proceeds in a robust manner. Insulin, through its activation of Akt, promotes the binding of GST-4E-BP[5A] to mTORC1 equally in the absence or presence of overexpressed Rheb; addition of an Akt inhibitor in the presence of overexpressed Rheb strongly inhibits the insulin stimulation of 4E-BP binding and the dissociation of PRAS40, but does not interfere with mTORC1 signaling to S6K1. Thus, insulin-induced displacement of PRAS40 and the consequent enhanced ability of other substrates to bind to raptor requires, and is a result of the activation of mTOR and Akt catalytic function, and is neither a primary cause of mTORC1 activation, nor we do not detect a significant subsidiary stimulation of mTORC1 signaling, at least in 293E cells.

Substantial genetic and biochemical evidence indicates that insulin activation of mTORC1 requires the action of Rheb-GTP (41). The present results prompt a reconsideration of the mechanism(s) by which Rheb activates mTORC1 signaling. Here we focus on the role of the direct interactions of Rheb with mTORC1, setting aside the questions of whether and to what extent Rheb-GTP interaction with FKBP38 (22) and activation of phospholipase D (21) contributes to mTORC1 activation. We observed that transiently expressed Rheb binds weakly to the mTOR catalytic domain, and in vitro this association is actually diminished by Rheb GTP charging. The evidence that this Rheb/mTOR interaction is physiologically significant was provided by the finding that mTOR bound to coexpressed wild type Rheb exhibits robust kinase activity in vitro, whereas mTOR bound to coexpressed inactive, nucleotide-deficient Rheb mutants is devoid of activity toward 4E-BP as well as to S6K1(355–525), which lacking the TOS motif, is a raptor-independent substrate (20). These results indicated that, at least in mTORC1, association with Rheb-GTP is needed for mTOR to acquire catalytic activity. The idea that insulin activation of mTORC1 is due, at least in part, to enhanced substrate access, first proposed by Wang et al. (5), was supported by the finding of Sancak et al. (6) that an 0.4 m NaCl wash of immunoprecipitated mTORC1, sufficient to reduce coprecipitating PRAS40, enhances the extent of 4E-BP phosphorylation achieved subsequently in vitro and eliminates an apparent insulin stimulation of mTORC1 activity assayed in vitro. These workers also reported that addition of Rheb-GTP can activate mTORC1 in vitro, and can overcome the inhibition by added PRAS40. How does Rheb-GTP activate mTORC1 in vitro and how is this activation related to Rheb action in vivo? Tamanoi and co-workers (42) confirmed the ability of Rheb-GTP to activate mTORC1 in vitro; they also observed that Rheb-GTP (but not Rheb-GDP) added to mTORC1 in vitro in the absence of Mg + ATP promotes the binding of 4E-BP to mTORC1, presumably by a mechanism that does not involve PRAS40 phosphorylation, either through a conformational change in mTORC1 or by displacement of an interfering protein, possibly PRAS40. We have been unable to confirm the ability of Rheb-GTP added in vitro to stimulate mTORC1 kinase activity toward 4E-BP or to enhance 4E-BP binding, both examined over a wide range of Rheb and 4E-BP concentrations. Nevertheless, our negative results and the results presented herein do not refute the possibility that Rheb-GTP promotes substrate access to mTORC1 in vivo by some phosphorylation-independent mechanism; the association of endogenous Rheb with endogenous mTOR has never been detected and (assuming such an association does occur) the putative phosphorylation-independent effect of Rheb-GTP on substrate access may simply be lost on cell extraction. It can be argued that Rheb overexpression may drive mTOR catalytic activity so strongly that displacement of PRAS40 and enhanced access of other substrates is obviated, whereas insulin may produce a less robust activation of endogenous Rheb whose impact on mTOR catalytic activity is amplified by a Rheb-GTP induced, phosphorylation-independent form of enhanced substrate access. Methods that monitor interactions in the intact cell, e.g. FRET, will be needed to further clarify the contribution of altered substrate access to the ability of Rheb to promote mTORC1 signaling in vivo. Nevertheless, the current data clearly demonstrate that phosphorylation-induced displacement of PRAS40 from mTORC1 is not caused by Rheb-GTP alone and is irrelevant to the ability of Rheb, and at least when overexpressed, to stimulate mTORC1 signaling in vivo. Based on available data, we conclude that in vivo, Rheb stimulation of mTORC1 signaling is predominantly, if not entirely due to stimulation of mTOR catalytic activity.

The present results, together with the previous results of Sancak et al. (6) and Sato et al. (42), also indicate that the conventional in vitro assay of mTORC1 kinase activity using 4E-BP phosphorylation is primarily an indirect measure of the extent of mTOR/Akt-induced displacement of PRAS40 from mTORC1 that occurred in vivo. When assayed in vitro, the PRAS40-depleted mTORC1 retrieved from insulin-stimulated cells catalyzes a more extensive phosphorylation of the added 4E-BP substrate. This assay is an inaccurate measure of the in vivo activation state of mTORC1 for several reasons; with regard to insulin, the phosphorylation of PRAS40(Ser183) in the absence of insulin is already 50% of its maximal insulin-stimulated level, a reflection of the ability of intracellular amino acids to promote mTORC1 activity. Consequently, the displacement of PRAS40 is more dramatically affected by the insulin-stimulated, Akt-catalyzed phosphorylation of PRAS40(Thr246); in this circumstance, mTORC1 catalyzed phosphorylation of 4E-BP in vitro is a much more accurate reflection of insulin-induced Akt activation than of Rheb-GTP induced mTOR activation. Certainly Akt, through its inhibitory action on the TSC, is also a regulator of Rheb GTP charging, and so Akt activity might be a valid surrogate for mTORC1 activity, at least downstream of insulin. Other mTORC1 activators, however, may not utilize Akt; thus Fonseca et al. (38), have shown that phorbol esters activate mTORC1 signaling without causing phosphorylation of PRAS40(Thr246) or PRAS40 displacement from mTORC1. These considerations indicate that in vitro assay of mTORC1 kinase using 4E-BP or other raptor-dependent substrates have limited reliability as measures of the activation state of mTORC1 in vivo. At this time, monitoring the phosphorylation state of direct mTORC1 substrates with phosphospecific antibodies in cell lysates remains the most reliable reflection of mTORC1 activity in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Diane Fingar for the gift of pRK7-Myc-raptor[6A] and David Schoenfeld for advice regarding statistics.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK17776 and CA73818.

- TOR

- target of rapamycin

- mTORC1

- mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1

- TSC

- tuberous sclerosis complex

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- DPBS

- Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline

- S6K1

- S6 kinase 1

- TOS

- TOR signaling.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M. N. (2006) Cell 124, 471–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hara K., Maruki Y., Long X., Yoshino K., Oshiro N., Hidayat S., Tokunaga C., Avruch J., Yonezawa K. (2002) Cell 110, 177–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim D. H., Sarbassov D. D., Ali S. M., King J. E., Latek R. R., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Sabatini D. M. (2002) Cell 110, 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Loewith R., Jacinto E., Wullschleger S., Lorberg A., Crespo J. L., Bonenfant D., Oppliger W., Jenoe P., Hall M. N. (2002) Mol. Cell. 10, 457–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang L., Rhodes C. J., Lawrence J. C., Jr. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24293–24303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sancak Y., Thoreen C. C., Peterson T. R., Lindquist R. A., Kang S. A., Spooner E., Carr S. A., Sabatini D. M. (2007) Mol. Cell. 25, 903–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vander Haar E., Lee S. I., Bandhakavi S., Griffin T. J., Kim D. H. (2007) Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 316–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang L., Harris T. E., Roth R. A., Lawrence J. C., Jr. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20036–20044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thedieck K., Polak P., Kim M. L., Molle K. D., Cohen A., Jenö P., Arrieumerlou C., Hall M. N. (2007) PLoS One 2, e1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kovacina K. S., Park G. Y., Bae S. S., Guzzetta A. W., Schaefer E., Birnbaum M. J., Roth R. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 10189–10194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oshiro N., Takahashi R., Yoshino K., Tanimura K., Nakashima A., Eguchi S., Miyamoto T., Hara K., Takehana K., Avruch J., Kikkawa U., Yonezawa K. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20329–20339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fonseca B. D., Smith E. M., Lee V. H., MacKintosh C., Proud C. G. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24514–24524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang L., Harris T. E., Lawrence J. C., Jr. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 15619–15627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nojima H., Tokunaga C., Eguchi S., Oshiro N., Hidayat S., Yoshino K., Hara K., Tanaka N., Avruch J., Yonezawa K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 15461–15464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beugnet A., Wang X., Proud C. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 40717–40722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Choi K. M., McMahon L. P., Lawrence J. C., Jr. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 19667–19673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schalm S. S., Fingar D. C., Sabatini D. M., Blenis J. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 797–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schalm S. S., Blenis J. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 632–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang J., Manning B. D. (2008) Biochem. J. 412, 179–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Long X., Lin Y., Ortiz-Vega S., Yonezawa K., Avruch J. (2005) Curr. Biol. 15, 702–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sun Y., Chen J. (2008) Cell Cycle 7, 3118–3123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bai X., Ma D., Liu A., Shen X., Wang Q. J., Liu Y., Jiang Y. (2007) Science 318, 977–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hara K., Yonezawa K., Weng Q. P., Kozlowski M. T., Belham C., Avruch J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 14484–14494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Avruch J., Long X., Ortiz-Vega S., Rapley J., Papageorgiou A, Dai N. (2009) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 296, E592–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roccio M., Bos J. L., Zwartkruis F. J. (2006) Oncogene 25, 657–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Long X., Ortiz-Vega S., Lin Y., Avruch J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 23433–23436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim E., Goraksha-Hicks P, Li L., Neufeld T. P., Guan K. L. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 935–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sancak Y., Peterson T. R., Shaul Y. D., Lindquist R. A., Thoreen C. C., Bar-Peled L., Sabatini D. M. (2008) Science 320, 1496–1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. von Manteuffel S. R., Dennis P. B., Pullen N., Gingras A. C., Sonenberg N., Thomas G. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 5426–5436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hong-Brown L. Q., Brown C. R., Kazi A. A., Huber D. S., Pruznak A. M., Lang C. H. (2010) J. Cell. Biochem. 109, 1172–1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu Q., Chang J. W., Wang J., Kang S. A., Thoreen C. C., Markhard A., Hur W., Zhang J., Sim T., Sabatini D. M., Gray N. S. (2010) J. Med. Chem. 53, 7146–7155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Logie L., Ruiz-Alcaraz A. J., Keane M., Woods Y. L., Bain J., Marquez R., Alessi D. R., Sutherland C. (2007) Diabetes 56, 2218–2227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Foster K. G., Acosta-Jaquez H. A., Romeo Y., Ekim B., Soliman G. A., Carriere A., Roux P. P., Ballif B. A., Fingar D. C. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 80–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gwinn D. M., Shackelford D. B., Egan D. F., Mihaylova M. M., Mery A., Vasquez D. S., Turk B. E., Shaw R. J. (2008) Mol. Cell. 30, 214–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carrière A., Cargnello M., Julien L. A., Gao H., Bonneil E., Thibault P., Roux P. P. (2008) Curr. Biol. 18, 1269–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carriere A., Romeo Y., Acosta-Jaquez H. A., Moreau J., Bonneil E., Thibault P., Fingar D. C., Roux P. P. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 567–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang L., Lawrence J. C., Jr., Sturgill T. W., Harris T. E. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14693–14697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fonseca B. D., Lee V. H., Proud C. G. (2008) Biochem. J. 411, 141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gwinn D. M., Asara J. M., Shaw R. J. (2010) PLoS One 5, e9197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ramírez-Valle F., Badura M. L., Braunstein S., Narasimhan M., Schneider R. J. (2010) Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 3151–3164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Avruch J., Hara K., Lin Y., Liu M., Long X., Ortiz-Vega S., Yonezawa K. (2006) Oncogene 25, 6361–6372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sato T., Nakashima A., Guo L., Tamanoi F. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12783–12791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]