Abstract

Muscle atrophy is caused by accelerated protein degradation and occurs in many pathological states. Two muscle-specific ubiquitin ligases, MAFbx/atrogin-1 and muscle RING-finger 1 (MuRF1), are prominently induced during muscle atrophy and mediate atrophy-associated protein degradation. Blocking the expression of these two ubiquitin ligases provides protection against muscle atrophy. Here we report that miR-23a suppresses the translation of both MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 in a 3′-UTR-dependent manner. Ectopic expression of miR-23a is sufficient to protect muscles from atrophy in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, miR-23a transgenic mice showed resistance against glucocorticoid-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. These data suggest that suppression of multiple regulators by a single miRNA can have significant consequences in adult tissues.

Keywords: MicroRNA, Skeletal Muscle, Skeletal Muscle Metabolism, Stress, Ubiquitin-dependent Protease, MAFbx/Atrogin-1, MuRF1

Introduction

Adult skeletal muscle has tremendous plasticity due in part to a dynamic balance between protein synthesis and degradation. Increased protein synthesis leads to muscle hypertrophy, whereas increased protein degradation leads to muscle atrophy. Physical activity, particularly resistance training, induces muscle hypertrophy, which is characterized by growth of existing myofibers and often brings about health benefits. On the other hand, various chronic diseases result in skeletal muscle atrophy, exacerbating the disease and compromising quality of life. Therefore, preventing and attenuating skeletal muscle atrophy is an important clinical issue.

Muscle atrophy occurs in response to fasting, chronic disease (e.g. cancer, diabetes, AIDS, sepsis, and sarcopenia), and disuse. Under these diverse conditions, atrophying muscles undergo accelerated protein degradation primarily through activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (1, 2) and a common series of transcriptional adaptations that together constitute an “atrophy program” (3). In multiple models of skeletal muscle atrophy, the muscle atrophy F-box/muscle-specific ubiquitin E3-ligases atrophy gene-1 (MAFbx/atrogin-1)3 and muscle RING-finger protein-1 (MuRF1) are up-regulated and appear to be essential for accelerated muscle protein loss (4). Overexpression of either MAFbx/atrogin-1 or MuRF1 in skeletal muscle fibers leads to atrophy or remarkable ubiquitination of muscle proteins, suggesting that increased expression of these genes induces muscle atrophy through protein degradation (5, 6). Interestingly, knock-out mice lacking either of the enzymes are resistant to various types of atrophy, suggesting that these two genes are essential for atrophy-related protein degradation (5, 6). Notably, neither knock-out mouse shows any muscle hypertrophy phenotype, suggesting these two genes are not involved in normal muscle growth.

Recent studies have revealed a new aspect of muscle gene regulation in which small, non-coding RNAs, known as microRNAs (miRNAs), play fundamental roles in diverse biological and pathological processes, including differentiation and morphogenesis of skeletal muscle (7). miRNAs are ∼22 nucleotides in length and inhibit target mRNA expression through translational repression or mRNA decay by interacting with their 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTR) (8–10). miRNAs are usually transcribed as pri-miRNAs that range in length from a few hundred to thousands of nucleotides, have a characteristic hairpin secondary structure, and are cleaved to pre-miRNAs by the RNase III enzyme, Drosha. These pre-miRNAs are exported from the nucleus by Exportin-5 and processed into ∼22 nucleotide miRNAs by another RNase III enzyme, Dicer. Finally, single-stranded miRNAs are integrated into the RNA-induced silencing complex that directs miRNA binding to the 3′-UTR of target mRNAs.

miRNAs inhibit target mRNA translation and thereby alter the levels of critical regulators. Thus, they play fundamental roles in diverse biological and pathological processes. In the skeletal muscle several muscle-specific miRNAs have been reported to play multiple roles in the control of muscle growth and differentiation. Chen et al. (11) showed that muscle-specific miRNAs, miR-1 and miR-133, down-regulate serum-responsive factor and histone deacetylase 4, respectively, to control muscle differentiation. It has also been shown that the myogenic regulatory factor, MyoD, induces miR-206 to promote myogenesis (12, 13). These studies have revealed the importance of muscle-specific miRNAs in skeletal muscle development, but there have been few reports on the function of miRNAs in adult skeletal muscle plasticity.

Here we report that a single miRNA regulates two key molecules involved in muscle atrophy, MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1. A bioinformatics approach identified miR-23a as a potential miRNA that targets MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1. We showed that miR-23a binds to the 3′-UTRs of both MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNAs to inhibit their translation and forced expression of miR-23a in myotubes and myofibers results in resistance to muscle atrophy. Furthermore, miR-23a transgenic mice were resistant to dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy. These findings strongly support a functional role for miR-23a in muscle physiology and suggest a new therapeutic target for skeletal muscle atrophy.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

C2C12 (American Type Culture Collection) mouse skeletal myoblasts were maintained at subconfluent densities in 20% FBS in DMEM. At 80–100% confluence, myogenesis was induced by changing the medium to 2% horse serum in DMEM. After incubating for 4 days in 2% horse serum in DMEM, more than 80% of cells formed multinuclear myotubes. To induce muscle atrophy in vitro, cells were incubated with 10 μm dexamethasone (Dex) in 2% horse serum in DMEM for 12 or 24 h. After treatment, cells were harvested in appropriate buffers or used for morphological analysis.

Myotube Transfection

C2C12 cells were seeded in 6-well plates 24 h before transfection. Cells were transfected with 1 μg of each vector or 20 nm concentrations of synthesized miRNA duplex (WAKO, Osaka, Japan) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in serum-free Opti-MEM (Invitrogen). Medium was replaced with FBS-containing medium after incubation for 6 h. 24 h after the plasmid transfection, the medium was replaced again with differentiation medium containing 2% horse serum in DMEM, and cells were cultured for 4 days. Finally, 10 nm (final concentration) concentrations of locked nucleic acid (LNA; underlined) antisense oligonucleotides (5′-GGA AAT CCC TGG CAA TGT GAT-3′) or random LNA (for negative control) were transfected and treated with 10 μm dexamethasone for 24 h.

Myotube Morphological Analysis

After Dex treatment, myotubes were photographed directly in culture plates using an IX71 fluorescent microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with an EM-CCD digital camera (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Shizuoka, Japan). The diameters of more than 50 myotubes were measured using ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Vectors

For pCXbG-miR-23a, a region including miR-23a was amplified from human genomic DNA by PCR using two primers, 5′-AAA GTC GAC CTT TCT CCC CTC CAG GTG C-3′ and 5′-AAG ATA TCT CGA GAC AGG CTT CGG GGC CTC TC-3′. The PCR product was digested with SalI and EcoRV and introduced into pCXbG at the XhoI and EcoRV sites. The chicken β-actin promoter in the pCXbG drives a common transcript for eGFP, and pri-miR-23a is processed to generate eGFP mRNA and mature miR-23a. pCXbG was generated from pCX-eGFP (14). The DNA fragment including the eGFP fused with the blasticidin resistance gene, XhoI, and EcoRV sites was amplified by PCR using pTracer-EF/Bsd (Invitrogen) and peGFP (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Mountain View, CA) as templates. This fragment was inserted into the EcoRI sites of pCX-eGFP to yield pCXbG.

For pLuc2EXN-atrogin-1 3′-UTR and pLuc2EXN-MuRF1 3′-UTR, a 300-bp fragment of the MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 3′-UTRs, including the putative miR-23a binding sites, were amplified from mouse cDNA by PCR using Ex TaqHS (TaKaRa, Osaka, Japan). Primer sequences for amplifying the MAFbx/atrogin-1 3′-UTR were 5′-TCT CTA GAA TCC CAG CAC ACG ACA ACA CTT C-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTC TCG AGG ACT CCG TTT CCA TGG CTG AC-3′ (reverse). Primer sequences for amplifying the MuRF1 3′-UTR were 5′-AAG AAT TCG GAA GTG TGT CTT CTC TCT GCT C-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAG AAT TCA AGG AAA GGA AGT AGG CAT CTC-3′ (reverse). Amplified fragments were cloned into the EcoRI and XbaI sites of the pLuc2EXN plasmid. pLuc2EXN was generated from pGL3-Control (Promega Co., Madison, WI) by cloning the Luc2 gene upstream of additional EcoRI and XbaI sites.

pLuc2EXN-atrogin-1 3′-UTRΔ and pLuc2EXN-MuRF1 3′-UTRΔ were generated by site-directed mutagenesis as described previously (15). Briefly, pLuc2EXN-atrogin-1 3′-UTR and pLuc2EXN-MuRF1 3′-UTR plasmids were used as templates for PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis with the QuikChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Primers used to generate pLuc2EXN-atrogin-1 3′-UTRΔ (mutated nucleotides are underlined) were 5′- GCC GAT GGA AAT TTA CAC ACT ATA ATT CCA CAT G-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAT GTG GAA TTA TAG TGT GTA AAT TTC CAT CGG C-3′ (reverse) primers. Primers 5′-GTA TGT TTT TAA AAT AAC CGT TTT GTA TAT ACT TGT ATA TG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAT ATA CAA GTA TAT ACA AAA CGG TTA TTT TAA AAA CAT AC-3′ (reverse) and additional mutagenic primers 5′-GTA TGC TTT TAA TCC AAC CGT TTT GTA TAT ACT TG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAA GTA TAT ACA AAA CGG TTG GAT TAA AAG CAT AC-3′ (reverse) were used for pLuc2EXN-MuRF1 3′-UTRΔ.

To confirm translation inhibition of MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 by miR-23a, we constructed expression vectors of FLAG-tagged MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 with/without their 3′-UTRs. Both MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 ORFs with 3′-UTRs were amplified from mouse cDNA by PCR using Ex TaqHS polymerase (TaKaRa) and cloned into the tibialis anterior (TA) vector (Invitrogen). Specific primers for the cloning of atrogin-1 ORF+3′-UTR were 5′-AGG ATC CAT GCC GTT CCT TGG GCA GGA C-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACT CGA GGC TTG TTT GCC AAG AGC ATG CAT AG-3′ (reverse). Primers for cloning MuRF1 ORF+3′-UTR were 5′-AAG GAT CCA TGG ATT ATA AAT CTA GCC TGA TTC CTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAG AAT TCT TTA TTT TTG AGG CAG AGT CTC TCT ATG-3′ (reverse). The PCR fragments, atrogin-1 ORF+3′-UTR and MuRF1 ORF+3′-UTR, were subcloned into pcDNA3.1 using BamHI-XhoI or BamHI-EcoRI sites, respectively. After cloning, a DNA fragment containing the FLAG tag of f:PGC-1 (a kind gift form Bruce Spiegelman, Harvard Medical School) was inserted upstream of each insert with a BamHI site. For expression vectors of FLAG-tagged MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 without their 3′-UTRs (atrogin-1 Δ and MuRF1Δ, respectively), we truncated the 3′-UTRs.

A reporter vector for pri-miR-23a∼27a∼24–2, pGL3–23P639 (16), was kindly provided by Dr. V. Narry Kim (Seoul National University). All plasmid DNAs were transformed and amplified in Escherichia coli DH5-α and were purified using the plasmid Midi kit (Qiagen, Duesseldorf, Germany).

Reporter Assay

HeLa cells (ATCC) were seeded in 6-well plates 24 h before transfection. Cells were transfected with 0.1 μg of pLuc2EXN-atrogin-1 3′-UTR, pLuc2EXN-MuRF1 3′-UTR, or pGL3–23P639 (16), 0.1 μg of LacZ, and 1.8 μg of pCXbG-miR-23a with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were lysed 24 h after transfection, and luciferase activity was measured using the luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). Luciferase activity was normalized to LacZ activity as previously described (17).

RNA Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells and animal tissues using ISOGEN (WAKO) according to the manufacturer's protocols, and 1 μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (RT; Invitrogen). Oligo-dT primers were used to generate cDNA, and an aliquot of the RT reaction was used directly for PCR with Ex TaqHS (TaKaRa, Osaka, Japan) and gene-specific primers. Primer sequences were: MAFbx/atrogin-1, 5′-GGG AGG CAA TGT CTG TGT TT-3′ and 5′-TTG TGA AAA AGT CCC GGT TC-3′; MuRF1, 5′-ACC GAG TGC AGA CGA TCA TCT C-3′ and 5′-AAA GTC AAT GGC CCT CAA GGC-3′; GAPDH, 5′-GTG GCA AAG TGG AGA TTG TTG CC-3′ and 5′-GAT GAT GAC CCG TTT GGC TCC-3′; β-actin, 5′-TGA CAG GAT GCA GAA GAA GA-3′ and 5′-GCT GGA AGG TGG ACA GTG AG-3′. GAPDH and β-actin were used as internal standards.

MicroRNA Analysis

For microarray expression profiling of miRNAs, C57BL6/J mouse skeletal muscle, embryonic fibroblast, and ES cell RNA preparations were labeled and hybridized to an Affymetrix GeneChip miRNA Array in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Normalized microarray data were managed and analyzed by GeneSpring (Agilent Technologies), and unsupervised hierarchical clustering using Pearson's correlation was performed with GenePattern software (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA).

The TaqMan MicroRNA reverse transcription kit and TaqMan MicroRNA assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were used according to the manufacturer's protocols for real-time PCR quantification of mature miRNA expression. In miRNA quantification, each RT reaction contained 10 ng of purified total RNA. The reactions were incubated for 30 min at 16 °C, 30 min at 42 °C, and 5 min at 85 °C. Real-time PCR reactions for each miRNA (10 μl volume) were performed in triplicate, and each 10-μl reaction mixture included 1 μl of RT product. Reactions were carried out with an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system in 96-well plates at 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min.

By using specific RT primers for pri- and pre-miR-23a, 500 ng of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with ThermoScriptRT (Invitrogen) as previously reported (18). Briefly, 500 ng of total RNA, 1 μl of 10 mm concentrations of specific RT primer (5′-TGG TAA TCC CTG GCA ATG TG-3′), and 2 μl of 10 mm dNTP were mixed, and distilled water was added to a total volume of 12 μl. The mixture was heated at 85 °C for 5 min, then at 57 °C for 5 min. After chilling on ice for 2 min, 4 μl of 5× cDNA synthesis buffer, 1 μl each of 0.1 m DTT, RNase inhibitor (ToYoBo, Osaka, Japan), and ThermoScriptRT (15 units/μl) were added to the mixture. The contents were gently mixed and incubated at 57 °C for 60 min and heated at 85 °C for 5 min to terminate the reaction. For quantification of pri- and pre-miR-23a, 1 μl of RT product was amplified by PCR using Ex TaqHS (TaKaRa) in a total reaction volume of 50 μl. Primer sequences for PCR were as follows: Pri-miR-23a forward (5′-TCC AGG TGC CAG CCT CTG-3′), pre-miR-23a forward (5′-CTG GGG TTC CTG GGG AT-3′), and a common reverse primer with the same sequence as the specific RT primer for pri- and pre-miR-23a. PCR conditions for both pri- and pre-miR-23a were 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 57 °C for 15 s, and extension at 72 °C for 15 s for extension. PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels containing 5 × 10−5 % ethidium bromide for 30 min, and fluorescent images were acquired under UV light by LAS3000 (FujiFilm Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Western Blot

Western blot was performed as described elsewhere (15) with following antibodies: anti-fast-MyHCs (MY-32, Sigma), anti-eIF3-f (Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA), anti-FLAG (M2, Sigma), and anti-γ-tubulin (AK-15, Sigma) antibodies.

Animal Experiments

Adult (8 weeks) male C57BL/6 mice (Clea Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) were housed in temperature-controlled quarters (21 °C) with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle and provided with water and food ad libitum. To induce skeletal muscle atrophy, 25 mg Dex/kg of body weight was injected intraperitoneally for 7 days at 9:00 a.m. For control mice, normal saline was injected intraperitoneally for 7 days. After Dex treatment, animals were sacrificed, and muscles were harvested in appropriate buffer or embedded with O.C.T. compound. The animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Tokyo and Waseda University.

Electric Pulse-mediated Gene Transfer

Electric pulse-mediated gene transfer was performed as described previously (17). Briefly, both TA muscles were injected with 20 μg of plasmid DNA under anesthesia (50 mg/kg of intraperitoneal sodium pentobarbital). Within 1 min after injection, an electrical field was delivered to the injected tibialis anterior muscle using a SEN-3401 electric stimulator (Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) through a Model 532 two-needle array (BTX Instrument Division Harvard Apparatus, Inc., Holliston, MA). Eight pulses that were 100 ms in duration, 1 Hz in frequency, and 100 V in amplitude (200 V/cm) were delivered by placing the needle arrays on the medial and lateral sides of the TA muscle so that the electrical field was perpendicular to the long axis of the myofibers. The mice were allowed to recover for 4 days before dexamethasone injection.

Generation of Transgenic Mice

For muscle-specific miR-23a transgenic mice, a 4.8-kb XhoI-EcoRI DNA fragment of the mouse muscle creatine kinase (MCK) promoter from the MCK-hGHpolyA plasmid (15) was excised and inserted upstream of the eGFP coding region of pCXbG-miR-23a using SalI-EcoRI sites. The muscle creatine kinase promoter, preferentially active in adult skeletal muscle, drove the expression of miR-23a independent of upstream signals. For conventional miR-23a transgenic mice, pCXbG-miR-23a was linearized using SalI-EcoRI sites and injected into C57BL6/J oocytes. Genotyping was carried out by PCR, and fluorescence microscopy was used to confirm transgene expression in adult skeletal muscles. Skeletal muscle samples were harvested from the F1 generation of transgenic lines (#345 and #355) and wild-type littermates (C57BL6/J background) at 8 weeks of age.

Immunohistochemistry

Anti-myosin heavy chain (MyHC) 2a (SC-71) and 2b (BF-F3) monoclonal antibodies were used as primary antibodies for immunostaining of O.C.T.-embedded cross-sections from mouse skeletal muscle (19). Mouse anti-dystrophin antibody (D8043, Sigma) with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody was used to identify muscle fiber shape. Cross-sections were fixed in PBS with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100, and incubated with primary antibody overnight. Secondary antibodies were either FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or R-PE-conjugated anti-mouse IgM (for MyHC 2a and MyHC 2b, respectively; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA). Finally, coverslips were mounted in VECTA SHIELD (Vector Laboratories, Ltd., Burlingame, CA). Cross-sectional area was measured with ImageJ Software.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± S.E. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) was determined by Student's t test or analysis of variance followed by the Dunnett test for comparisons between two groups or multiple groups, respectively.

RESULTS

miR-23a Interacts with 3′-UTRs of MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNAs

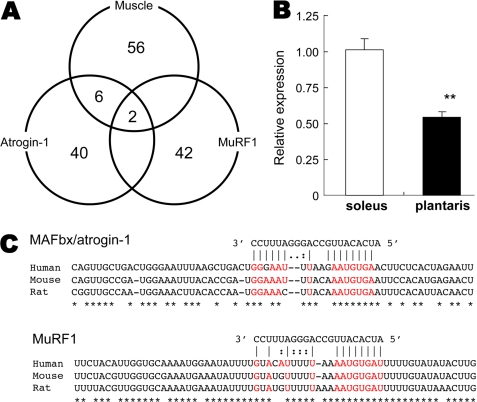

To investigate miRNA function in muscle atrophy, we first employed microarrays to identify miRNAs in skeletal muscle (supplemental Table S1). We then narrowed down the miRNAs that could potentially interact with MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 using a bioinformatics approach. As a result, 48 and 44 candidate miRNAs were nominated to interact with MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 3′-UTRs, respectively. These results were based on computationally predicted target genes found in the online data base TargetScan5.1 (Fig. 1A). Among them, two miRNAs, miR-23a and 23b, were nominated as common candidate miRNAs that could potentially interact with both MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1. Another online data base, MicroCosm Targets, also nominated miR-23a and 23b as candidates. The sequence for miR-23a differs by a single nucleotide from that of miR-23b, but otherwise the two genes have identical seed sequences; hence, they likely target the same mRNAs. The functional difference between them has yet to be determined. Notably, microarray (supplemental Table S1) and TaqMan probe-based quantitative real-time-PCR (data not shown) revealed dominant expression of miR-23a in skeletal muscle. miR-23a has been previously reported to be up-regulated in hypertrophic hearts of mice with transgenic expression of activated calcineurin A (20) and mice treated with a β-adrenergic agonist (21). However, there is no report addressing the physiological function of miR-23a in skeletal muscle. We first found that miR-23a was highly expressed in slow-twitch soleus muscle compared with fast-twitch plantaris muscle (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Identification of miRNAs that target both MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 in skeletal muscle. A, microarray analysis sets the top 10% of miRNAs (n = 64) as highly expressing miRNAs in skeletal muscle. An online data base (TargetScan) nominated 48 and 44 candidate miRNAs that could target MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 3′-UTR, respectively. Among them, only two miRNAs, miR-23a and 23b, could target both genes. These were also found to be highly expressing miRNAs in skeletal muscle. B, fiber type difference in expression of miR-23a is shown. Expressions of miR-23a in slow-twitch soleus and fast-twitch plantaris muscle were determined by real-time PCR. C, sequence alignment of putative miR-23a binding sites in the 3′-UTRs of MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 show a high level of complementarity and sequence conservation. Values are relative to soleus muscle (n = 4). Data are presented as mean ± S.E. **, p < 0.01.

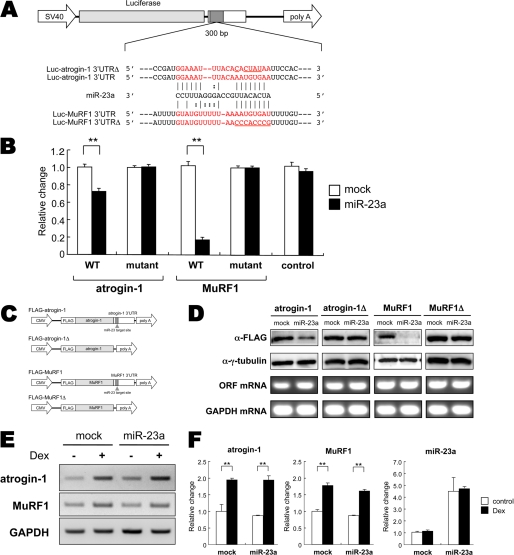

Our bioinformatics analysis revealed that the putative miR-23a binding sites in the 3′-UTRs of both MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 are highly conserved in human, mouse, and rat (Fig. 1C). To investigate the functional interaction of miR-23a and these molecules, the 3′-UTRs of MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA were subcloned downstream of a luciferase reporter (Fig. 2A). We co-transfected a miR-23a overexpression vector (pCXGb-miR-23a) and each reporter vector (pLuc2EXN-atrogin-1 3′-UTR and pLuc2EXN-MuRF1 3′-UTR) into HeLa cells and measured luciferase activity 24 h later. We also constructed reporter vectors with mutations in the putative miR-23a binding sites of the 3′-UTRs (pLuc2EXN-atrogin-1 3′-UTRΔ and pLuc2EXN-MuRF1 3′-UTRΔ). A luciferase vector without any 3′-UTR sequence, pLuc2EXN, was also transfected as a negative control. As expected, luciferase activity was markedly reduced when the miR-23a expression vector was co-transfected with pLuc2EXN-atrogin-1 3′-UTR or pLuc2EXN-MuRF1 3′-UTR (Fig. 2B). The miR-23a-induced decrease in luciferase activity was not observed for any of the mutant reporter vector. Luciferase mRNA levels were not affected by miR-23a overexpression (supplemental Fig. S1), suggesting that miR-23a mediated translational repression of MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 in a 3′-UTR-dependent manner.

FIGURE 2.

miR-23a targets and suppresses MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expression. A, the MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 300 bp-long 3′-UTRs, including putative miR-23a binding sites, were cloned downstream of luciferase under the SV40 promoter. The reporter vector constructs are shown for wild-type UTRs (Luc-atrogin-1 3′-UTR and Luc-MuRF1 3′-UTR) and their mutants (Luc-atrogin-1 3′-UTRΔ and Luc-MuRF1 3′-UTRΔ). B, HeLa cells were co-transfected with Luc-atrogin-1 3′-UTR (WT), Luc-atrogin-1 3′-UTRΔ (mutant), Luc-MuRF1 3′-UTR (WT), Luc-MuRF1 3′-UTRΔ (mutant), or original vector (control) along with either the miR-23a expression vector or a mock vector. Luciferase activity was measured, and the presented values indicate luciferase activity relative to mock co-transfection (n = 6). C, expression vectors for MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 are shown. A DNA fragment of either atrogin-1 or MuRF1 was cloned downstream of FLAG. FLAG-tagged expression vectors were constructed with (FLAG-atrogin-1 and MuRF1) or without the full-length 3′-UTR (FLAG-atrogin-1Δ and MuRF1Δ). D, miR-23a inhibits atrogin-1 and MuRF1 protein expression but not mRNA in a 3′-UTR-dependent manner. HeLa cells were co-transfected with each FLAG-tagged atrogin-1, MuRF1, atrogin-1Δ, and MuRF1Δ expression vector in addition to either a miR-23a expression vector or a mock vector. Protein expression was detected with anti-FLAG antibody. γ-Tubulin was used as a reference control. RT-PCR measured mRNA expression of constructs (ORF for atrogin-1 or MuRF1). GAPDH was used as an internal control. E, miR-23a does not affect Dex-induced mRNA expression of atrogin-1 or MuRF1. F, expression of MAFbx/atrogin-1, MuRF1, and miR-23a RNA was quantified using quantitative PCR. Values are relative to the mock control (n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± S.E. **, p < 0.01.

To confirm the translational inhibition of these genes, we cloned the MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 genes, including their 3′-UTRs, into an expression vector with a FLAG tag (Fig. 2C). We also generated expression vectors for MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 without 3′-UTRs (atrogin-1Δ and MuRF1Δ, respectively) as controls (Fig. 2C). Protein, but not mRNA expression in FLAG-tagged MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1, was reduced by co-transfection with the miR-23a expression vector (Fig. 2D). On the other hand, neither mRNA nor protein expression in atrogin-1Δ and MuRF1Δ was suppressed by miR-23a (Fig. 2D).

Next, we confirmed whether overexpression of miR-23a affected endogenous mRNA expression in MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1. C2C12, a mouse myoblast cell line was transfected with an miR-23a expression vector and treated with 10 μm Dex for 12 h. Despite high expression of miR-23a, no change was observed in MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA expression in response to dexamethasone treatment (Fig. 2, E and F), suggesting that miR-23a could interact with the 3′-UTRs of MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 to down-regulate their translation.

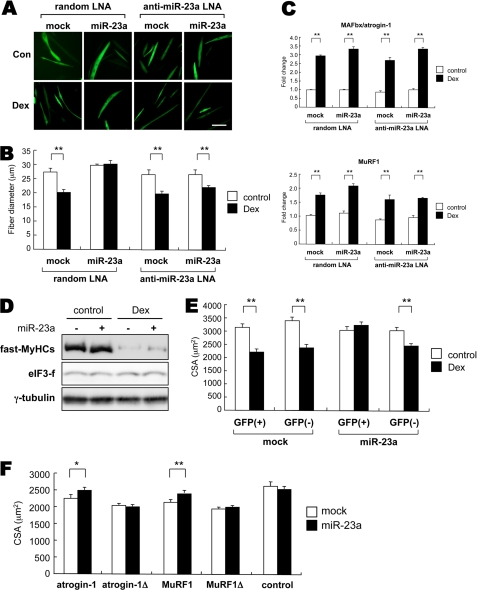

miR-23a Promotes Resistance to Dexamethasone-induced Muscle Atrophy in Vitro and in Vivo

We investigated miR-23a function using an in vitro model of muscle atrophy with forced expression of miR-23a. The miR-23a expression vector with GFP was transfected into C2C12 cells followed by induction of myogenesis. We then treated the myotubes with 10 μm Dex for 24 h and measured myotube diameter using GFP expression as a transgene marker. We also employed LNA antisense-mediated silencing of miR-23a to ascertain if miR-23a expression is necessary for atrophy resistance. LNA antisense oligonucleotides bind selectively to miRNAs and down-regulate their function by forming rigid duplexes with their complementary miRNAs (22) (supplemental Fig. S2). In mock-transfected cells, myotube diameter decreased significantly with Dex treatment (27.9 ± 1.2 versus 20.7 ± 1.0 μm, p < 0.001), whereas the diameters of myotubes expressing miR-23a did not decrease with random control LNA oligos (29.2 ± 0.1 versus 29.2 ± 1.2 μm) (Fig. 3, A and B, left). As expected, an anti-miR-23a LNA oligos canceled myotube atrophy resistance despite miR-23a overexpression (mock, 26.3 ± 1.2 versus 19.3 ± 0.8 μm, p < 0.001; miR-23a, 26.2 ± 1.1 versus 22.4 ± 0.9 μm, p < 0.01) without affecting MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA expression (Fig. 3, A–C). We also examined if the miR-23a-mediated modulation of MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expressions affects their target proteins. As a result, fast-MyHCs, which are targets for MuRF1, were decreased with dexamethasone treatment, and overexpression of miR-23a attenuated the Dex-induced protein degradation of fast-MyHCs (Fig. 3D). On the other hand, eIF3-f, which is a target for MAFbx/atrogin-1, was not decreased despite of high dose of dexamethasone (500 μm for 24 h).

FIGURE 3.

miR-23a overexpression counteracts dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy. A and B, The myotube diameter of mock or miR-23a expression vector-transfected C2C12 myotubes after dexamethasone treatment is shown. After myogenesis was induced, either random LNA-oligo (control) or LNA-oligo against miR-23a (anti-miR-23a) was co-transfected followed by 10 μm Dex treatment for 24 h. Transfected eGFP-positive myotubes were analyzed (n > 50). The bar indicates 50 μm. C, miR-23a overexpression or knockdown did not affect dexamethasone-induced MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA expressions (n = 3). D, shown is miR-23a attenuated Dex-induced decreases in target protein for MuRF1, fast-MyHC. C2C12 myotubes were transfected with either synthesized miR-23a duplex or control duplex and treated with 500 μm dexamethasone for 24 h. γ-Tubulin was used as a reference control. E, CSA of miR-23a or mock vector-injected TA muscle. Saline or 25 mg/kg Dex was injected into mice (n = 4 per treatment group) for 7 days. Cross-sections were stained with anti-MyHC 2b antibody for fast-twitch fiber staining. eGFP-positive fast-twitch muscle fibers (GFP(+)) were analyzed. eGFP-negative fast-fiber CSA (GFP(−)) values were also determined and used as an internal control. n > 80 fibers per group. F, CSA of miR-23a expression vector or mock vector-transfected muscle fibers with atrogin-1/MuRF1 with/without its 3′-UTR is shown. miR-23a and mock expression vectors were transfected with either atrogin-1, MuRF1, atrogin-1Δ, or MuRF1Δ into tibialis anterior muscle by electric pulse-mediated gene transfer (n >100 fibers per group). Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

We next analyzed the effect of miR-23a overexpression on atrophy resistance in adult muscle fibers by using electric pulse-mediated gene transfer to introduce pCXbG-miR-23a into the TA. Given that dexamethasone induces fast-twitch fiber-oriented atrophy (23), we quantified the cross-sectional area (CSA) of GFP and MyHC 2b double-positive fibers. We found that fiber CSA in mock-transfected muscle decreased significantly (3178.8 ± 130.7 versus 2249.7 ± 86.5 μm, p < 0.001) after 7 days of dexamethasone treatment (25 mg/kg daily intraperitoneal injection), whereas miR-23a positive fibers were obviously resistant to muscle atrophy (3013.5 ± 99.4 versus 3150.0 ± 92.6 μm) (Fig. 3E). The CSA for GFP-negative fast-twitch fibers was also quantified as an internal control and revealed that dexamethasone could induce atrophy in fast-twitch fibers (mock, 3320.8 ± 100.5 versus 2411.6 ± 77.8 μm, p < 0.001; miR-23a, 2947.5 ± 113.5 versus 2431.2 ± 75.8 μm, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3E).

To confirm whether the inhibition of muscle atrophy was caused by miR-23a-induced down-regulation of the two genes in their 3′-UTR-dependent manner, either MAFbx/atrogin-1 or MuRF1 expression vector with/without its 3′-UTRs (same vectors shown in Fig. 2C) was co-transfected with the miR-23a expression vector into adult muscle fibers. The CSA values for eGFP positive fibers were determined for each case because the co-expression rate of co-transfected plasmids in skeletal muscle fibers is more than 99% (24, 25). Compared with the blank vector-transfected control, CSA for fibers transfected with either MAFbx/atrogin-1 or MuRF1 was significantly lower, suggesting that overexpression of either enzyme could induce muscle atrophy and that miR-23a overexpression counteracted muscle atrophy in a 3′-UTR-dependent manner (Fig. 3F). Collectively, these results suggest that miR-23a expression is sufficient to attenuate skeletal muscle atrophy in vitro and in vivo.

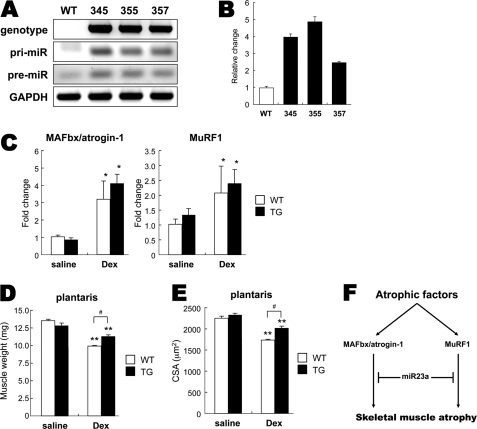

miR-23a Transgenic Mice Are Resistant to Muscle Atrophy

We found that electric pulse-mediated gene transfer of miR-23a into adult mouse skeletal muscle attenuated dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy in vivo (Fig. 3E). This finding prompted us to generate miR-23a transgenic mice because our model was insufficient for analyzing whole muscle resistance to atrophy. We first attempted to generate transgenic mice with muscle-specific overexpression of miR-23a with eGFP driven by the muscle creatine kinase promoter (supplemental Fig. S3A). Although the DNA constructs were generated and expressed successfully in differentiated myotubes (supplemental Fig. S3B), we obtained seven lines of transgenic mice that all expressed low levels of the miR-23a transgene. Because of technical difficulties associated with generating muscle-specific transgenic mice overexpressing miR-23a, we settled on an alternative approach. To this end we generated miR-23a transgenic mice under a powerful (chicken β-actin) promoter and successfully obtained three transgenic lines with high-level expression of the miR-23a transgene (Fig. 4, A and B).

FIGURE 4.

miR-23a transgenic mice are resistant to muscle atrophy. Shown are representative images of tail genomic DNA genotyping and pri- and pre-miR-23a analysis by PCR (A) and quantification of mature miR-23a in muscle biopsy by real-time PCR (n = 3) (B). C, TG and wild type littermates (WT) were injected with 25 mg/kg Dex. After 24 h, MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNAs were quantified by RT-qPCR in plantaris muscle (n = 3 per group). D and E, mice were injected with 25 mg/kg dexamethasone for 7 days and sacrificed. Muscle weight (n = 8) (D) and CSA of fast-twitch fibers (fibers >200) (E) were measured in plantaris muscle. Data are presented as the mean ± S.E. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, compared with WT control; #, p < 0.05 between Dex-treated WT and TG. F, shown is a model for the role of miR-23a in muscle atrophy. The integrated suppression of MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 by miR-23a results in resistance to muscle atrophy.

The miR-23a TG mice looked similar to WT littermates in body weight (supplemental Fig. S4B). We first quantified MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA levels in transgenic mouse skeletal muscle because forced miR-23a expression may affect basal and inducible expression patterns for both genes. Mice were sacrificed 24 h after dexamethasone injection, and mRNA expression in plantaris muscle was quantified by quantitative real-time-PCR. As expected, MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNA levels in transgenic animals (TG) were comparable with those in the wild type (WT) littermates (Fig. 4C). This suggests that miR-23a transgene expression does not affect MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 mRNAs in the same manner as it does in vitro.

Next, we treated mice with dexamethasone to test if transgenic mice were resistant to skeletal muscle atrophy. After 7 days of dexamethasone treatment, mice were sacrificed, and muscle weight was measured. In transgenic mice, plantaris muscle weight was significantly higher than that of the wild type littermates (9.94 ± 0.13 (WT) versus 10.85 ± 0.19 mg (TG), p < 0.01) (Fig. 4D). Given that dexamethasone is known to induce fast-twitch fiber-oriented atrophy, we also quantified CSA for fast-twitch muscle fibers in transgenic and wild type plantaris muscle. Loss in CSA was significantly lower in transgenic mice than in wild type mice (1739.1 ± 26.8 (WT) versus 1907.9 ± 31.1 μm (TG), p < 0.001) (Fig. 4E). Consistent with our findings in cultured myotubes and electric pulse-mediated gene transfer experiments, forced expression of miR-23a in skeletal muscle results in resistance against muscle atrophy.

Because miR-23a is reported as a cardiac hypertrophy-related miRNA and is activated by calcineurin signaling, we sought to investigate potential cardiac phenotypes. Although increased expression of miR-23a was observed in transgenic mice heart tissue (supplemental Fig. S4A), the heart weight and β-MyHC, which is known to be up-regulated in hypertrophic heart, were not affected in transgenic animals (supplemental Fig. S4, C and D).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that miR-23a is a novel regulator of muscle atrophy through post-transcriptional regulation of both MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 and plays a key role in protection against skeletal muscle atrophy. We demonstrated that a single miRNA down-regulates two specific regulators that function in the same physiological context. miR-23a interacts with the 3′-UTRs of both MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 to suppress their translation, and forced expression of miR-23a in cultured myotubes and adult skeletal muscle results in resistance to glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy. These findings suggest that forced expression of miR-23a in skeletal muscle could provide resistance against atrophy by regulating both MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 genes (Fig. 4F). Although miR-23a is reported as a cardiac hypertrophy-related miRNA, our transgenic model did not show any cardiac abnormalities. If accompanied by a proper drug delivery system, miR-23a could serve as a viable therapeutic target for this clinically relevant problem that can be affected by and exacerbate many chronic diseases.

Transcription factors regulate multiple targets at once by binding to specific promoter sequences, allowing a single transcription factor to orchestrate gene expression to shift toward a specific profile. miRNAs also contribute to this process (26). Recent studies using proteomic approaches have demonstrated that a single miRNA can suppress the production of hundreds of proteins (27, 28). The multi-targeting ability of miRNAs is attracting more attention and is a topic of vigorous research. In this study miR-23a repressed MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 at the protein level without affecting mRNA expression (Fig. 2, B and D–F). Although this repression was not very strong, the integrated repression of both proteins in the same physiological context induced significant resistance to atrophic signals.

MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 are both important regulators of atrophy, but recent studies have focused on the functional differences between them. MAFbx/atrogin-1 induces muscle atrophy by repressing muscle protein synthesis through MyoD and eukaryotic initiation factor 3-f degradation (29, 30). On the other hand, MuRF1 targets myosin heavy chains and myofibril-associated proteins, resulting in loss of sarcomere structural stability (2, 31). Our data suggest that miR-23a affects MuRF1 more than it does MAFbx/atrogin-1. The physiological implications of MuRF1-oriented regulation by miR-23a merits further research considering that target function could define miRNA function.

Cardiac and skeletal muscles are classified as striated muscle, and they show many similarities in structure and gene expression. However, it remains unclear whether their miRNAs are somewhat different even if they target the same mRNAs. The muscle atrophy regulators, MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1, are expressed in both types of muscle. It was previously reported that miR-23a targets MuRF1 to induce cardiac hypertrophy (21); however, our results in cultured myotubes and transgenic mice clearly demonstrate that miR-23a does not promote skeletal muscle hypertrophy but prevents myotube atrophy (Fig. 3 and 4E). Such a discrepancy may arise from the difference in MuRF1 function in cardiac and skeletal muscle. In cardiac muscle, gene disruption of MuRF1 and its homologues results in severe cardiac hypertrophy, demonstrating that MuRF1 functions to prevent pathological cardiac hypertrophy (32, 33). Such gene disruption induces milder hypertrophy in skeletal muscle (33). These results suggest that MuRF1 serves to maintain homeostasis in cardiac muscle but acts as a regulator of atrophy in skeletal muscle. This may underlie the difference in miR-23a function in cardiac and skeletal muscle. These results collectively imply that miR-23a can target the same genes in both cardiac and skeletal muscle but exhibit distinct functions given the difference in target gene function in each muscle.

A recent report revealed that miR-23a targets regulators of alternative splicing, CUGBP and ETR-3-like (CELF) proteins, thereby influencing alternative splicing in post-natal heart development (34). Surprisingly, miR-23a transgenic mice did not show cardiac abnormalities or hypertrophy, although we observed a 2.5-fold induction of miR-23a expression in their hearts (supplemental Fig. S4). This may indicate that although expression of miR-23a is required during heart development, uncoordinated induction is not sufficient to induce abnormalities.

The functional role of stress-responsive miRNAs in adult tissues has been gaining attention (35). Various stresses induce miRNAs (36, 37), and this has been clearly demonstrated in cardiac muscle. Pressure overload or calcineurin activation induces pathological cardiac hypertrophy (38, 39), contexts in which miR-195 and miR-208 play important roles (20, 37). Several miRNAs, including miR-23a, are up-regulated during hypertrophic stress, and miR-23a overexpression in cardiomyocytes induces myocyte hypertrophy (20). Lin et al. (21) reported that miR-23a is induced by β-adrenergic stimuli or activated calcineurin via NFATc3 in cardiomyocytes. We tested whether the calcineurin-NFAT pathway was sufficient for inducing miR-23a expression in skeletal muscle by treating skeletal myocytes with a β-adrenergic agonist or activating the calcineurin pathway. We observed no alteration in miR-23a expression, although miR-23a reporter activity was slightly increased with NFAT overexpression or constitutively active calcineurin (supplemental Fig. S5, A–C). This implies that the transcriptional control of miR-23a in skeletal muscle is different from that in cardiomyocytes.

Muscle-specific miRNAs encoded in the MyHC intron regulate host gene expression in cardiac muscle in response to stress signals (40). miR-208a, which is encoded in the fast MyHC intron, regulates slow MyHC, including its intronic miR-208b and miR-499. It is interesting to note that evolutionarily conserved miRNAs regulate host gene expression in an inter-locus manner, which strongly implies the importance of the evolutionarily conserved “functional unit” in certain miRNAs. It is widely known that some miRNAs are transcribed as a polycistronic miRNA cluster in which two or three miRNAs are generated from a common pri-miRNA, another example of a functional unit. miR-23a is included in a polycistronic miRNA cluster with miR-27a and miR-24–2 (16), which is conserved from zebrafish to human. Such unique transcriptional control is thought to contribute to highly coordinated regulation of miRNA target genes. Interestingly, miR-23b, which is nearly identical to miR-23a, also resides in this polycistronic miRNA cluster, suggesting that this cluster consists of evolutionarily conserved functional units. Elucidation of the transcriptional control of this miRNA cluster may provide significant insights into the physiological relevance of the miRNAs encoded therein.

miRNA regulation is an attractive target for clinical therapies. Several miRNAs have been implicated in disease development, such as cancer, heart disease, and cholesterol/lipid metabolism. Our results suggest that miR-23a may attenuate muscle atrophy. Therapeutic manipulation of miR-23a expression could potentially maintain skeletal muscle function by suppressing MAFbx/atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expression. Our discovery of the miR-23a physiological role in preventing the atrophy program should lay the foundation not only for further understanding the mechanisms that underlie muscle wasting in diverse diseases but also for developing novel therapies for these debilitating conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. R. Sanders Williams (Duke University) for encouragement. We also thank Dr. Atsushi Inoue (National Research Institute for Child Health and Development, Japan), Dr. Eric N. Olson (University of Texas), Dr. Bruce Spiegelman (Harvard Medical School), Dr. Masanobu Satake (Tohoku University, Japan), and Dr. V. Narry Kim (Seoul National University, Korea) for vector constructs.

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-aid for Young Investigators (A) 18680047 and 21680049 (to T. A.) and in part by the “Establishment of Consolidated Research Institute for Advanced Science and Medical Care,” Encouraging Development Strategic Research Centers Program, the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan, and the Takeda Science Foundation (2009) and Suzuken Memorial Foundation (2009).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and Table S1.

- MAFbx/atrogin-1

- muscle atrophy F-box/muscle-specific ubiquitin E3-ligases atrophy gene-1

- MuRF1

- muscle RING-finger 1

- miR

- microRNA

- Dex

- dexamethasone

- MyHC

- myosin heavy chain

- LNA

- locked nucleic acid

- CSA

- cross-sectional area

- NFAT

- nuclear factor-activated T cells

- TA

- tibialis anterior

- R-PE

- R-Phycoerythrin

- RT

- reverse transcriptase

- TG

- transgenic

- eGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Glass D. J. (2010) Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 13, 225–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cohen S., Brault J. J., Gygi S. P., Glass D. J., Valenzuela D. M., Gartner C., Latres E., Goldberg A. L. (2009) J. Cell Biol. 185, 1083–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lecker S. H., Jagoe R. T., Gilbert A., Gomes M., Baracos V., Bailey J., Price S. R., Mitch W. E., Goldberg A. L. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 39–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sacheck J. M., Hyatt J. P., Raffaello A., Jagoe R. T., Roy R. R., Edgerton V. R., Lecker S. H., Goldberg A. L. (2007) FASEB J. 21, 140–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bodine S. C., Latres E., Baumhueter S., Lai V. K., Nunez L., Clarke B. A., Poueymirou W. T., Panaro F. J., Na E., Dharmarajan K., Pan Z. Q., Valenzuela D. M., DeChiara T. M., Stitt T. N., Yancopoulos G. D., Glass D. J. (2001) Science 294, 1704–1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gomes M. D., Lecker S. H., Jagoe R. T., Navon A., Goldberg A. L. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 14440–14445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Rooij E., Olson E. N. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2369–2376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen K., Rajewsky N. (2007) Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Djuranovic S., Nahvi A., Green R. (2011) Science 331, 550–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huntzinger E., Izaurralde E. (2011) Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen J. F., Mandel E. M., Thomson J. M., Wu Q., Callis T. E., Hammond S. M., Conlon F. L., Wang D. Z. (2006) Nat. Genet. 38, 228–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim H. K., Lee Y. S., Sivaprasad U., Malhotra A., Dutta A. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 174, 677–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosenberg M. I., Georges S. A., Asawachaicharn A., Analau E., Tapscott S. J. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 175, 77–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Okabe M., Ikawa M., Kominami K., Nakanishi T., Nishimune Y. (1997) FEBS Lett. 407, 313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Akimoto T., Pohnert S. C., Li P., Zhang M., Gumbs C., Rosenberg P. B., Williams R. S., Yan Z. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19587–19593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee Y., Kim M., Han J., Yeom K. H., Lee S., Baek S. H., Kim V. N. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 4051–4060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akimoto T., Sorg B. S., Yan Z. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287, C790–C796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jiang J., Lee E. J., Gusev Y., Schmittgen T. D. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 5394–5403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schiaffino S., Gorza L., Sartore S., Saggin L., Ausoni S., Vianello M., Gundersen K., Lømo T. (1989) J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 10, 197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Rooij E., Sutherland L. B., Liu N., Williams A. H., McAnally J., Gerard R. D., Richardson J. A., Olson E. N. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 18255–18260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin Z., Murtaza I., Wang K., Jiao J., Gao J., Li P. F. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12103–12108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elmén J., Lindow M., Silahtaroglu A., Bak M., Christensen M., Lind-Thomsen A., Hedtjärn M., Hansen J. B., Hansen H. F., Straarup E. M., McCullagh K., Kearney P., Kauppinen S. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 1153–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schakman O., Gilson H., Thissen J. P. (2008) J. Endocrinol. 197, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Donà M., Sandri M., Rossini K., Dell'Aica I., Podhorska-Okolow M., Carraro U. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 312, 1132–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rana Z. A., Ekmark M., Gundersen K. (2004) Acta Physiol. Scand. 181, 233–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lim L. P., Lau N. C., Garrett-Engele P., Grimson A., Schelter J. M., Castle J., Bartel D. P., Linsley P. S., Johnson J. M. (2005) Nature 433, 769–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baek D., Villén J., Shin C., Camargo F. D., Gygi S. P., Bartel D. P. (2008) Nature 455, 64–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Selbach M., Schwanhäusser B., Thierfelder N., Fang Z., Khanin R., Rajewsky N. (2008) Nature 455, 58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tintignac L. A., Lagirand J., Batonnet S., Sirri V., Leibovitch M. P., Leibovitch S. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2847–2856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lagirand-Cantaloube J., Offner N., Csibi A., Leibovitch M. P., Batonnet-Pichon S., Tintignac L. A., Segura C. T., Leibovitch S. A. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 1266–1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clarke B. A., Drujan D., Willis M. S., Murphy L. O., Corpina R. A., Burova E., Rakhilin S. V., Stitt T. N., Patterson C., Latres E., Glass D. J. (2007) Cell Metab. 6, 376–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fielitz J., Kim M. S., Shelton J. M., Latif S., Spencer J. A., Glass D. J., Richardson J. A., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2486–2495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Witt C. C., Witt S. H., Lerche S., Labeit D., Back W., Labeit S. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 350–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kalsotra A., Wang K., Li P. F., Cooper T. A. (2010) Genes Dev. 24, 653–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bommer G. T., Gerin I., Feng Y., Kaczorowski A. J., Kuick R., Love R. E., Zhai Y., Giordano T. J., Qin Z. S., Moore B. B., MacDougald O. A., Cho K. R., Fearon E. R. (2007) Curr. Biol. 17, 1298–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kulshreshtha R., Ferracin M., Wojcik S. E., Garzon R., Alder H., Agosto-Perez F. J., Davuluri R., Liu C. G., Croce C. M., Negrini M., Calin G. A., Ivan M. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 1859–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Rooij E., Sutherland L. B., Qi X., Richardson J. A., Hill J., Olson E. N. (2007) Science 316, 575–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hill J. A., Karimi M., Kutschke W., Davisson R. L., Zimmerman K., Wang Z., Kerber R. E., Weiss R. M. (2000) Circulation 101, 2863–2869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Molkentin J. D., Lu J. R., Antos C. L., Markham B., Richardson J., Robbins J., Grant S. R., Olson E. N. (1998) Cell 93, 215–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van Rooij E., Quiat D., Johnson B. A., Sutherland L. B., Qi X., Richardson J. A., Kelm R. J., Jr., Olson E. N. (2009) Dev. Cell 17, 662–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.