Abstract

Apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) plays important structural and functional roles in plasma high density lipoprotein (HDL) that is responsible for reverse cholesterol transport. However, a molecular understanding of HDL assembly and function remains enigmatic. The 2.2-Å crystal structure of Δ(185–243)apoA-I reported here shows that it forms a half-circle dimer. The backbone of the dimer consists of two elongated antiparallel proline-kinked helices (five AB tandem repeats). The N-terminal domain of each molecule forms a four-helix bundle with the helical C-terminal region of the symmetry-related partner. The central region forms a flexible domain with two antiparallel helices connecting the bundles at each end. The two-domain dimer structure based on helical repeats suggests the role of apoA-I in the formation of discoidal HDL particles. Furthermore, the structure suggests the possible interaction with lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase and may shed light on the molecular details of the effect of the Milano, Paris, and Fin mutations.

Keywords: Apolipoproteins, Atherosclerosis, Cholesterol, HDL, Lipoprotein, Lipoprotein Structure

Introduction

Heart disease remains the leading cause of death in the United States (1). Plasma levels of HDL are negatively correlated with the incidence of atherosclerosis, and the mechanisms of the anti-atherogenic effects of HDL are mainly related to its involvement in the pathways of reverse cholesterol transport (RCT)2 (2). ApoA-I, the major protein component of HDL, plays four important roles during RCT as follows: stabilizing the HDL particle structure; interacting with the ABCA-I transporter (3); activating LCAT (4); and acting as a ligand for the hepatic scavenger receptor B1 (5).

As illustrated schematically in Fig. 1A, plasma apoA-I (243 amino acids, 28 kDa) is encoded by two regions of the gene. The first 43 residues are encoded by exon-3 and the 44–243-region is encoded by exon-4 (6). Sequence analysis has suggested that the exon-3-encoded region forms a G* helix, and the exon-4-encoded region contains 10 tandem 11/22-residue repeats thought to form lipid-binding class A amphipathic helices that represent the fundamental lipid-binding motif (7–9). In prior studies, we derived consensus sequences for the two types of 11-residue repeats (A and B) that divide the exon-4-encoded region into a series of putative helical segments with different homologies (10). This analysis describes the five AB repeat motifs in the central region of apoA-I as follows: AB1(H2/H3), AB2(H4), AB3(H5), AB4(H6), and AB5(H7). This analysis (8, 10), NMR assignments (11, 12), and most recently hydrogen-deuterium exchange measurements (13) have provided different distributions, flexible regions, and positions for these putative helical tandem repeats. Segment deletion and point mutation studies have elucidated the possible conformation and function for each helical segment (14–22).

FIGURE 1.

Overall structure of Δ(185–243)apoA-I dimer. A, illustrations of the helix distribution from sequence analysis, consensus sequence model analysis, Δ(185–243)apoA-I crystal structure, and hydrogen exchange of plasma apoA-I and Δ(1–43)apoA-I crystal structure. Exon-3-encoded region (residues 1–43) is green. Exon-4 -encoded region (44–243) is ice-blue. Consensus sequence peptide (CSP) A and B homology sequences are in purple and cyan, respectively. Prolines are labeled in yellow. Five AB repeats are labeled with black dotted lines with arrows. B, overall structure of Δ(185–243)apoA-I monomer. C, two different views showing the homodimer with dimerization interface composed of two antiparallel five AB repeats. The N-terminal helix bundles are connected by the central segment hinge. Each region is colored to correspond to A. D, temperature factor distribution. The orange dotted circles show the most flexible regions.

ApoA-I exists in lipid-free, lipid-poor, and lipid-bound states and, as a consequence, has a flexible and adaptable structure similar to the molten globular state (23). This flexible nature has hindered high resolution structural studies. A single low resolution (∼4 Å) crystal structure of Δ(1–43)apoA-I has been reported (24). Although this crystal structure substantiated many features of the secondary structure predictions, the low resolution hinders a detailed analysis of the structure such as stabilizing and dimer interactions. The crystal structure did not provide any information about the N-terminal 43 residues that are suggested to be essential to stabilize the structure of lipid-free apoA-I (16, 19).

Here, we report the 2.2-Å crystal structure of Δ(185–243)apoA-I. The structure substantiates many features of the secondary structure predictions of the type A and B helical repeats with different homologies. The structure also shows the molecular details of the stabilization of lipid-free apoA-I by the N-terminal exon-3-encoded residues and suggests the role of dimerization in the assembly of HDL. In addition, the structure suggests how the central domain may function as hinge region to facilitate a monomer to dimer conversion. With a semicircular backbone formed from antiparallel helical repeats, the structure allows us to model the formation of discoidal HDL particles with different geometries. The central domain may form a tunnel to translocate lipid during the interaction with LCAT. Finally, the structure provides molecular details that may underlie the structural and functional effects of apoA-I mutations such as Milano, Paris, and Fin (25–27).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construct Design

The intrinsic lipid binding properties and large hydrophobic surface of apoA-I result in substantial aggregation at low protein concentration (15). The structural flexibility of apoA-I that can adapt to the significant geometry changes from discoidal nascent HDL to spherical mature HDL leads to multiple conformations (23). The C terminus (residues 185–243) (15, 21) of apoA-I has the highest hydrophobicity and is responsible for the initiation of lipid binding and self-association substantiated by our studies of the apoA-I peptide (residues 198–243). Furthermore, our mutation studies have clearly identified the region 185–190 as a flexible loop (17). This evidence led us to delete the C terminus (residues 185–243) to overcome the problems of aggregation.

Previous studies have utilized different expression systems to produce mutated forms of apoA-I that result in extraneous residues at the N terminus. Expression in mammalian cell lines produces apoA-I with the six residues pro-sequence (17, 20). Expression in insect cell lines as a His-tagged protein with a TEV cleavage site results in five non-native residues. Similarly, adenovirus expression systems result in an extraneous six amino acids (18, 20, 22). Multiple studies have suggested that the N-terminal region is involved in stabilizing interactions with other regions of the protein (16, 20). Consequently, such extraneous residues might disrupt the conformation and interactions in other parts of the molecule. Thus, we developed the His6-MBP-TEV expression system in Escherichia coli to produce wild type and truncated apoA-I with a single glycine at the N terminus derived from the TEV cleavage site according to the protocol described before (28).

Gateway recombination cloning was used to facilitate the construction of the fusion protein expression vector. PCR was used to generate PCR products with corresponding products flanked with attB1 and attB2 on N and C termini, respectively, and the inserted TEV protease recognition site right before the N terminus of the wild type or truncated human apoA-I proteins. PCR products were recombined by Gateway cloning into the donor vector pDONR221 (Invitrogen) to yield entry clones and then into destination vector pDEST-His6-MBP (from addgene.org originating from Dr. David Waugh) to generate His6-MBP-apoA-I fusion expression vectors.

Protein Expression and Purification

Native wild type and Δ(185–243)apoA-I proteins were overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) CodonPlus-RIL (Stratagene) cells at 30 °C with 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 4 h. Cells were collected and lysed in a buffer containing 50 mm sodium phosphate, 150 mm NaCl, 25 mm imidazole, pH 8.0. Soluble fusion proteins were purified using HisTrap columns (GE Healthcare) with an FPLC system (GE Healthcare). The purified fusion proteins were treated with His-tagged TEV protease (Invitrogen) to release the target proteins with one extra non-native glycine at the N terminus. A second run through the HisTrap column removed the His-tagged TEV protease, His6-MBP tag, and left the pure target proteins to elute from the column. Fractions containing target proteins were pooled, concentrated, and loaded onto a Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare) gel filtration column. Native Δ(185–243)apoA-I was eluted as two peaks with retention times corresponding to dimer and monomer proteins.

Se-Met-labeled Δ(185–243) was overexpressed in E. coli B834(DE3) cells (EMD Biosciences) at 30 °C with 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for overnight and purified in the same manner as the native Δ(185–243)apoA-I with 2 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (Hampton Research) in the purification buffer.

Crystallization and Data Collection

Crystals of the native and Se-Met-labeled Δ(185–243)apoA-I were grown at room temperature using the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method. The well buffer contained 0.15 m KBr, 30% polyethylene glycol monomethyl ether 2000 for native and 0.1 m KSCN, 30% polyethylene glycol monomethyl ether 2000 for Se-Met. The crystals appeared in 1–2 weeks and grew to full size in 4–8 weeks with a typical dimension of 0.05 × 0.1 × 0.4 mm3 for native and of 0.05 × 0.1 × 0.6 mm3 for Se-Met. Fresh crystals were transferred into a cryo-protectant buffer containing 15% glycerol and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for data collection. A full 2.0-Å native data set was collected from a single crystal at the Brookhaven National Laboratory X4C beamline and processed with HKL2000 (29). A full 2.4-Å single wavelength anomalous dispersion data set was collected from a single crystal at the Brookhaven National Laboratory X4C beamline at the peak wavelength 0.9788 Å. Data collection statistics are shown in supplemental Table S1.

Structure Determination, Refinement, and Model Building

The diffraction from Δ(185–243)apoA-I was phased by the single wavelength anomalous dispersion method, using the 2.4-Å Se-Met Δ(185–243)apoA-I data set collected at the peak wavelength 0.9788 Å. The PHENIX suite (30) was used to solve the structure. Phenix.autosol was used to identify the three Se-Met sites in the protein and generate a high quality electron density map with the phase derived from the selenium sites. Phenix.autobuild was used to build the model of Se-Met Δ(185–243)apoA-I. After iterative rounds of model building and refinement, 180 of total 184 amino acids were identified in the model of Se-Met Δ(185–243)apoA-I.

The structure of native Δ(185–243)apoA-I was phased by molecular replacement using phenix.automr with Se-Met Δ(185–243)apoA-I as the search model. Subsequent refinement of coordinates, individual B factors, and TLS groups (31) were done in phenix.refine with tight geometric B factor and hydrogen bond restraints. Crystallographic refinement statistics and structure validation are shown in supplemental Table S1. Chimera (32) and Modeler (33) were used to create the different models with the Δ(185–243)apoA-I and Δ(1–43)apoA-I crystal structures.

RESULTS

Overall Structure

In this study, we generated a homogeneous Δ(185–243)apoA-I and obtained a 2.2-Å structure of native Δ(185–243)apoA-I that identified residues 3–182 in the structural model (supplemental Table S1 and Fig. S1).

As illustrated in Fig. 1B, one molecule of Δ(185–243)apoA-I (∼80% helix) forms an approximate half-circle. Each monomer interacts with a symmetry-related molecule to form a homodimer. The dimer has an approximately semi-circular architecture with a height of ∼17 Å and a diameter of ∼110 Å (Fig. 1C). The backbone of the dimer consists of two long antiparallel helices with proline kinks located at positions that punctuate the junctions of the tandem sequence repeats. At each end of the dimer there is a loose bundle composed of four helices and an extended segment. The N-terminal exon-3-encoded segment of each monomer forms the first helix. An extended strand and a short second helical region form the connection to the third long parallel helix of the bundle in each monomer. The fourth helix formed by the C-terminal residues of the symmetry-related molecule is incorporated into the helix bundle burying the hydrophobic residues and stabilizing the bundle. This organization results in an in-register interaction of the two central helical regions (H5 and AB3) with the two antiparallel helices connecting the helix bundle at each end. As shown in Fig. 1D, the central helical segment has the highest temperature factors, suggesting a degree of flexibility in this region.

Repeat Sequence Homology, Sequence Conservation and Structural Relationship

Fig. 1, B and C, shows the structure of the monomer and dimer, respectively, with the structural elements colored in accordance with the repeating sequence and homology features illustrated in Fig. 1A. The structure demonstrates close concordance to the sequence analysis.

In the monomer (Fig. 1B), the N-terminal 43 residues (exon-3-encoded) form a major helix (residues 7–34) and a minor helix (residues 37–41). The major helix starts at Pro7 and the helix is kinked at Val21. The minor helix, oriented at ∼90° to the major helix, forms a connecting turn to the first 11-residue B repeat of H1 (residues 44–54). This B repeat has an extended structure antiparallel to the major helix. Notably, this repeat has extremely low homology (∼8%) to the consensus sequence and to the other B repeats in apoA-I. The second B unit of H1 (residues 55–65) that has the highest homology (∼47%) forms a short helical extension to this extended region terminated by Gly65. Pro66, at the start of the first A repeat of H2 together with Val67, Thr68 forms a turn. The remainder of this A repeat and the following 22-residue AB segment H2/H3(AB1) that does not contain a proline forms a continuous helix. The high homology 22 residue AB repeats that follow form an almost continuous helix that is kinked by the proline residues at the start of each A segment.

The dimer backbone has an exact AB antiparallel pairing in these five continuous AB repeats with the central region H5(AB3) and prolines in register (Figs. 1C and 6A). The last two C-terminal repeats (H6(AB4) and H7(AB5)) interact with the N-terminal bundle domain of the symmetry-related molecule stabilizing the dimer formation.

FIGURE 6.

Five AB repeats form backbone and dimerization interface in the Δ(185–243)apoA-I and Δ(1–43)apoA-I crystal structures. A, illustrations of the dimerization interface of Δ(185–243)apoA-I and Δ(1–43)apoA-I crystal structure. Exon-3-encoded region (residues 1–43) is green. Exon-4-encoded region (residues 44–243) is ice blue. Consensus sequence peptide (CSP) A and B homology sequences are in purple and cyan, respectively. Prolines are labeled in yellow. Red dotted region shows the five AB repeat dimerization interface. B, comparing the dimerization interfaces of Δ(185–243)apoA-I and Δ(1–43) apoA-I crystal structures.

Sequence conservation analysis of apoA-I from 31 species identified eight completely reserved residues (34). Five of these are identified in our structure: Tyr18, Pro66, Arg83, Tyr115, and Pro121. All of these residues are in the helical structure as predicted except Pro66. Pro66 forms a turn with Val67 and Thr68 as shown in Fig. 1, B and C, instead of forming a helical structure at the start position of each A repeat like other prolines. This conservation implies Pro66 might have a vital function during the conformational change of apoA-I from the lipid-free to lipid-bound state.

N-terminal Helix Bundle

The helix bundle formed by the N terminus of the monomer and the C-terminal helix of the symmetry-related molecule buries the hydrophobic amino acids. Two aromatic clusters and two π-cation interactions are major features in the stabilization of the helical bundle.

The two aromatic clusters (N and C), one at each end of the bundle, are shown in Fig. 2. The N aromatic cluster formed by Trp8, Phe71, and Trp72 together with nearby leucines forms a hydrophobic environment that holds together the N terminus of the first helix, the second helical B unit of H1, and the helix of the first A unit of H2. At the other end of the bundle, Phe33, Phe104, and Trp108 form the C aromatic cluster that holds together the N-terminal helix and H4(AB2), again together with nearby leucines. The two aromatic clusters work as staples to hold the helix bundle together at each end. Phe71, Trp72 and Trp72, Trp8 in the N-aromatic cluster form typical edge to plane π-π interactions, whereas Phe33 and Trp108 form a less stable offset stacked π-π interaction suggesting the C aromatic cluster interaction is weaker and thus more readily to be disrupted by lipid.

FIGURE 2.

Structure of Δ(185–243)apoA-I dimer consists of N-terminal helix bundles and central segment hinge. N-terminal helix bundles of Δ(185–243)apoA-I dimer are stabilized by two aromatic clusters (N and C) and two π-cation interactions (N and C).

In the N-terminal helix bundle domain, π-cation interactions (35) are located at the N and C termini. Lys23 and Trp50 form the C π-cation interaction that holds the extended B section of H1 toward the helix bundle as shown in Fig. 2. Trp50 is in the middle of this section, and the π-cation interaction holds this extended section in a defined structure toward the N-terminal major helix presumably reducing the flexibility. Another π-cation interaction between Trp8 and Arg61 (Fig. 2) holds the short helix formed by the second B unit of H1 toward the N-terminal helix to cover the N-terminal aromatic cluster.

Central Segment Hinge

The H5(AB3) region of opposing monomers forms two antiparallel helices connecting the helix bundles at each end (Fig. 2). The B factor distribution and less defined electron density showed this to be the most flexible part of the structure as illustrated in Fig. 1D. This repeat is unique among the repeating AB motifs. Leucines and a centrally located alanine are the only hydrophobic residues. The two antiparallel helices have the hydrophobic residues lining their interacting faces where Leu122 and Leu126 form a leucine zipper-like interaction with Leu137 and Leu141 on the symmetry-related molecule. Centrally located in the two helices, the Ala130 residues face each other and leave a large space (∼5 Å) between them. In addition and unique to this repeat, a single Arg123 occupies a position at the edge of the hydrophobic face that projects toward the hydrophobic region at each end of the antiparallel AB pair. Finally, residues 135–141 do not form a well defined α-helical structure but form a loose approximately helical segment stabilized by a salt bridge (Glu136–Lys140).

Salt Bridge Interactions

Salt bridge interactions add stability to the helix conformation (36). Generally, i + 4 salt bridges are more stabilizing than the i + 3 salt bridge, whereas triad salt bridges such as Arg-Glu-Arg stabilize the α-helix by more than the additive contribution of two single salt bridges (37).

Inspection of the helical wheel of the AB consensus sequence (10) shown in Fig. 3A suggests that intra-helical i + 4 salt bridges, Glu5–Arg9, Arg11–Glu15, and Glu16–Arg20, may provide important stabilization of the AB repeats, whereas i + 3 salt bridges Glu4–Arg7 and Glu15–Arg18 may provide additional stabilization. The strongest stabilization may come from a salt bridge triad, Arg11–Glu15–Arg18. Analysis of the five AB repeat units from the sequence of apoA-I suggests that modification of these potential salt bridge interactions through sequence variation occurs resulting in different contributions to the stability of each helical region.

FIGURE 3.

Salt bridge interactions in monomer and between monomers. A, illustration of the potential salt bridges in the CSP-AB model and observed salt bridges in the five AB repeats from the monomer of the crystal structure on helix wheel diagrams. Salt bridges between i,i + 4 are connected with electric blue dotted lines with arrows. Salt bridges between i,i + 3 are connected with cyan dotted lines with arrows. Residues labeled with red star form salt bridge triads. Unusual salt bridges are connected with red dotted lines with arrows. Negatively charged residues are red; positively charged residues are blue; hydrophobic residues are white; prolines are yellow; neutral residues are light green, and histidine residues are blue and white. B, two major (N and C) salt bridge networks consisting of salt bridges between monomers and within the monomer hold the dimer of the crystal structure together. Arg171 and Arg151 labeled by red dotted lines are the positions corresponding to the Milano and Paris mutation, respectively. C, H6(AB4) and H4(AB2) region is the possible LCAT interaction region. Surface colored with residue charge is shown to identify possible charged residues that are responsible for the formation of salt bridges with LCAT.

Inspection of the structure identified the salt bridges of the monomer illustrated in the helix wheel of each segment shown in Fig. 3A. All the salt bridges occur in the five AB repeating sequences suggesting they function to stabilize the backbone of the structure.

H2/H3(AB1) and H7(AB5) have two salt bridges, one i + 4 and one i + 3 each. In addition, there is an unusual Lys88–Asp89 salt bridge in H2/H3(AB1). Analysis of the helix wheels indicates a potential for more salt bridges suggesting that these two AB repeats are more flexible perhaps due to their function as the start and end of the five AB repeat backbone. H4(AB2) and H6(AB4) have four salt bridges, two i + 4 and two i + 3 each. In addition, there are two strong stabilizing salt bridge triads in H4(AB2) and one in H6(AB4). The A unit of H6(AB4) has the highest homology (∼61%) and H6(AB4) is believed to be the region that interacts with LCAT. Unlike the H4(AB2) sequence in which the salt bridges are distributed evenly over the hydrophilic surface of the helix, the salt bridges of H6(AB4) are located in one region providing a possible interacting surface for LCAT. (H5)AB3 has one i + 4, two i + 3 salt bridges, and one salt bridge triad.

Interestingly, most of the salt bridges occur close to the start or end of the AB motifs adjacent to the prolines suggesting that these salt bridges may help stabilize the adjacent proline kinks. Notably, the Glu120–Arg123 salt bridge crosses Pro121 (between H4 and H5) and may provide stabilization to hold Arg123 into the hydrophobic area in the central hinge segment.

Salt bridges between monomers provide additional stability to the dimer. The supplemental Fig. S2 shows the two symmetry unique regions of the four areas of inter-molecular salt bridges in the dimer. Lys96–Glu169 and the triads Asp89–Arg173–Glu92 and Glu85–Arg177–Asp89 with the relay of the Arg173 and addition of Lys88 form the N-Inter-salt bridge network as shown in Fig. 3B. This salt bridge network stabilizes the interaction of H2/H3(AB1) in one molecule with the antiparallel H7(AB5) in the C terminus. The C-Inter-salt bridges formed by His155–Glu111–Arg151 are shown in supplemental Fig. S2. With the relay of Glu111 and Arg151, it connects the intra-monomer salt bridges Lys106–Glu110, Lys107–Glu111, and Glu147–Arg151 to form an extensive C-Inter-salt bridge network as shown in Fig. 3B. These salt bridge networks stabilize the interaction of H4(AB2) in one molecule with the C-terminal H6(AB4). Lack of salt bridges between H5(AB3) repeats enhances the flexibility of the hinge region. All the intermolecular salt bridges are situated on the outside surface of the backbone formed by the five AB repeats. This positioning results in a clear hydrophobic inside surface to the backbone. The distances of the salt bridges in the monomer and between the monomers are listed supplemental Table S2.

Surface Properties

The supplemental Fig. S3 shows the well defined hydrophobic interface between the five AB-repeating motifs. The H5(AB3) repeats only need a small change in orientation at the proline kink or at the less structured 135–141 residues to expose the hydrophobic residues.

In the N-terminal bundle, an opening between the extended region formed by the first B repeat in H1 and the body of the bundle is apparent as shown in Fig. 4A. This may represent an entrance site for phospholipid and/or free cholesterol into the hydrophobic core. Interestingly, the C π-cation is directly accessible through the opening suggesting that it may function as a gate to the hydrophobic core.

FIGURE 4.

Surface properties of the Δ(185–243)apoA-I crystal structure. A, possible lipid entrance tunnel at the N-terminal helix bundle with surface colored according to the residue hydrophobicity. Enlarged figure shows the direct access to the C π-cation from the tunnel with the surface colored according to the residue charge. B, inside and outside view of the amphipathic tunnel formed by the central AB repeats (H5/H5) with surface colored according to the residue hydrophobicity or charge. The amphipathic central tunnel has a hydrophilic outside surface composed of charged residues and a hydrophobic inside surface of hydrophobic residues with Ala130 in the center of the tunnel forming a possible portal for the transportation of lipid by LCAT.

An additional interesting feature is the significant opening (central tunnel) formed by the opposing positions of Ala130 in the middle of H5(AB3) repeats clearly visible in Fig. 4B. The central tunnel has a strongly charged outside surface (Glu125, Glu128, Lys133, and Glu136) and a hydrophobic inside surface (Leu126, Leu137, and Ala130).

DISCUSSION

Stabilization Effect of N-terminal 43 Residues

The structure clearly demonstrates the role of the N-terminal 43 residues encoded by exon-3 in forming a helical structure and making intra-molecular interactions with the first section of the exon-4-encoded repeats and inter-molecular interactions with the C terminus of the second molecule in the dimer to form a loose bundle. In addition to forming a helix bundle to cover the hydrophobic surface, it contributes Trp8 and Phe33 to aromatic clusters at each end of the helix bundle that stabilizes the bundle. It also forms two π-cation interactions with H1 that hold the extended segment of the first B repeat of H1 in place. This extended segment may work as a gating mechanism for the entrance of lipid into the hydrophobic core as shown in Fig. 5A. Disruption of the two π-cation interactions by lipid and concomitant dissociation of the N-terminal helix and H1 may open the gate allowing lipid access to the hydrophobic core and disruption of the aromatic clusters at each end. Unhinging of the bundle can then occur at the loop between the short helical second B sequence of H1 and the first A repeat of H2 (Gly65, Pro66, Val67, and Thr68) and at the top of the bundle at the short helical segment at right angles to the bundle axis (Ala37–Gln41). This dissociation and unhinging would result in the extension of the helical backbone. Minor adjustment of the torsion angles of Glu80 may contribute to this unhinging by straightening the helix encompassing repeat H2/H3(AB1). Pairing with the C terminus (residues 185–243) not included in our structure would result in a closed double belt of helices to form the nascent HDL disc. The salt bridges between the antiparallel five AB repeats of the dimer pair maintain the integrity of the backbone. Opening of the N-terminal helix bundle would result in a hydrophobic inside surface of the dimer, although the outside surface remains hydrophilic as shown in supplemental Fig. S3.

FIGURE 5.

Stabilization of first 43 residues for apoA-I and possible monomer conformation in solution. A, stabilization of the first 43 residues for apoA-I in solution and a possible mechanism for unhinging of the N-terminal helix bundle upon lipid binding. B, possible Δ(185–243)apoA-I monomer. The two conformational states interconvert dependent on protein concentration with the central AB repeats (H5) folding or unfolding.

Two-domain Structure in Solution and Monomer to Dimer Conversion

Several studies have suggested that apoA-I has two folding domains with a more rigid N-terminal domain (residues 1–189) and a less organized C-terminal domain (residues 190–243) (15, 19, 21). In our studies, deletion of the C-terminal region (residues 185–243) resulted in an increase of the helical content by ∼8% (supplemental Fig. S4A and Table S3) with increased unfolding cooperativity (supplemental Fig. S4, C and D) and no change in tertiary structure (supplemental Fig. S4B), further supporting the concept that the 1–184-residue region is an independent folding domain. 8-Anilino-1-naphthalene sulfonate fluorescence (supplemental Fig. S5A), n-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside binding (supplemental Fig. S4E), 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine clearance (supplemental Fig. S5C), and EM data (supplemental Fig. S5B) provide additional evidence for independent folding. The C terminus (residues 185–243) is probably flexible in solution without defined structure and little helical content until it binds to lipid. Our solution characterization clearly showed a monomer-dimer equilibrium (supplemental Fig. S5D) with concentration, and the dimer observed in the crystal structure has a higher α-helical content (∼80%) than the ∼59% observed in dilute solution (supplemental Table S3).

The structural analysis indicates that H5(AB3) is the most flexible region in the structure. Indeed, residues 136–141 exist in a poorly folded “helix-like” conformation. Our previous studies of Δ(136–143)apoA-I suggested that this region has little helical conformation (18). These observations lead us to suggest that the H5(AB3) repeat may function as a hinge in the monomer form of Δ(185–243)apoA-1 in dilute solution. The last two AB repeats may fold back to replace the corresponding segments from the opposing molecule of the dimer as shown in Fig. 5B. Recent hydrogen-deuterium exchange experiments (13) suggest that residues 7–44, 54–65, 70–78, 81–115, and 147–178 form α-helices, although residues 116–146 and 179–243 lack defined structure. The major difference in helical distribution in the crystal structure compared with hydrogen exchange data is in the central section as shown in Fig. 1A, which is unstructured. The 185–243-residue segment also lacks structure in solution. In summary, our crystal structure together with the hydrogen-deuterium exchange experiments substantiates the two-domain structure of apoA-I in solution with H5(AB3) functioning as a hinge determining the monomer to dimer conversion with protein concentration.

Comparison with Structure of Δ(1–43)ApoA-I

The prior crystal structure of Δ(1–43)apoA-I shows the formation of a dimer of dimers (24). Although the resolution of the Δ(1–43)apoA-I crystal structure is low, dimerization of the five AB-repeating motifs is clearly a common feature exhibiting the same five AB repeat antiparallel-interacting motifs as shown in Fig. 6. This evidence further supports the concept that the five AB repeats function as the major dimerization interface and as the main backbone to determine the size of the HDL particle.

The absence of the N-terminal 43 residues to stabilize the lipid-free structure and shield the hydrophobic surface of the helices results in a dimer-dimer interaction to cover the hydrophobic surface. Small changes in the proline kinks between the five AB-repeating motifs occur to satisfy the overall geometry and result in a different shape (curvature) of the five AB-repeating motifs. Furthermore, in the Δ(1–43)apoA-I structure, the first B unit of H1 (44–55) only forms a partial helix as in Δ(185–243)apoA-I. H1(BB), and the first A unit of H2 forms a dimer interaction with the C-terminal H8(BB) and H9(A) repeat region. This implies a potential dimerization ability and possible dimerization interface in full-length apoA-I. To illustrate these features, we used our structure of Δ(185–243)apoA-I as backbone and aligned the 165–182-residue segment with that of Δ(1–43)apoA-I to derive a possible conformation for the full length of apoA-I as shown in supplemental Fig. S6. Following lipid binding and unfolding of the N-terminal helix bundle, interaction of the exposed H1(BB) and the first A unit of H2 with the C-terminal H8(BB) and H9(A) to form the dimer results in a “double loop” model.

Formation of HDL and Different Geometries of HDL Particles

The “horseshoe-shaped” Δ(1–43)apoA-I crystal structure (24) has led to the widely accepted “double belt” model for apoA-I on discoidal HDL particles. Different models for two apoA-I molecules bound to ∼96 Å diameter POPC-apoA-I discoidal particles have been proposed with different interactions of the N- and C-terminal regions of the two monomers (38–43). A different double belt model (44, 45) has been proposed from sequence analysis and simulation studies. A common feature of these models is the registration of H5/H5 repeats (38–40, 44). Sequence analysis (44) and sequence conservation analysis (46) propose three pairs of buried inter-helical salt bridges in the double loop model in discoidal HDL. MD simulations of spherical and discoidal HDL models suggest that two buried inter-helical salt bridges Asp89–Arg177 and Glu111–His155 are conserved to maintain the H5/H5 registration of the double belt model, although Glu78–Arg188 is unstable (45, 47). These two salt bridges are identified in our crystal structure at the outside surface with very strong interactions (2.6 Å for Asp89–Arg177 and 2.9 Å for Glu111–His155) as shown in Fig. 3B. Our structure shows that the H5/H5 registration is present in the lipid-free structure and does not require major structural rearrangements on formation of an HDL particle. Thus, the apoA-I dimer of our crystal structure may represent the intermediate state during the process of HDL assembly. Upon binding to lipid, the helix might rotate to expose the hydrophobic surface to the lipids and thus bury the inter-helical salt bridges identified on the outside surface in our crystal structure.

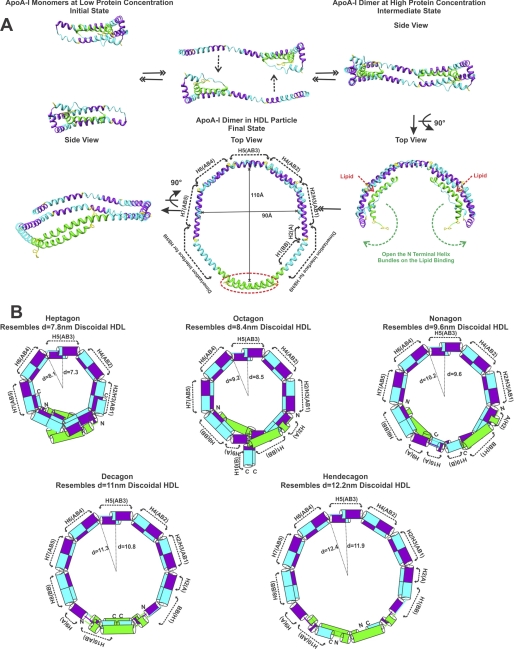

Fig. 7A suggests a mechanism for the formation of the discoidal HDL particle from the monomer of apoA-I in solution based on sequential “unhinging” of the N-terminal bundle. In the initial state, monomeric apoA-I has a two-domain structure with the organization of the N-terminal region similar to that proposed for monomeric Δ(185–243)apoA-I with H5(AB3) forming a loop and undefined structure in the C-terminal segment 185–243. Interaction with lipid, perhaps mediated by the C terminus, may bring the monomer apoA-I molecules into close proximity resulting in a transformation to the dimer intermediate state. Our crystal structure represents this intermediate state because of the high protein concentration during the crystallization. Increased proximity to the phospholipid surface of the membrane bilayer (possibly because ofthe interaction with ABCA-I) leads to opening of the N-terminal helix bundle by disruption of the π-cation and aromatic cluster interactions through the gate in the N-terminal helix bundle thus exposing the inside hydrophobic surface of the dimer. The apoA-I dimer can then insert into defects in the membrane surface. Unhinging of the N-terminal domain residues and extended helix formation in the region before H2/H3(AB1) results in binding to the C-terminal region of the opposing molecule to form a double belt discoidal HDL particle as final state. As demonstrated in Fig. 7A, changing the loop regions before AB1 in the crystal structure into helix and adjusting Pro66 to the same kink angle as Pro121 results in the final state. This final state model has a dimension ∼90 × ∼110 Å and illustrates the possible dimerization region with H8 and H9.

FIGURE 7.

Discoidal HDL particles formation mechanism and size variation. A, possible mechanism of discoidal HDL particle formation from monomer apoA-I in solution through three states. B, HDL models based on the crystal structure resemble different sizes of discoidal HDL particles.

The dimerization of Δ(185–243)apoA-I as an antiparallel double belt with the five repeating AB motifs produces a semicircular backbone with a radius of ∼110 Å. The stabilization of the structure by the first 43 amino acids together with the intermolecular salt bridges on the outside surface of the double belt may restrict the proline kink angles and further stabilize the structure. With the five AB-repeating motifs as backbone, progressive unhinging of the N-terminal bundle by forming different dimerization interfaces with the C-terminal region (residues 185–243) together with small changes in the proline kinks can change the diameter of the HDL particles. Lipid content may be the dominant factor to determine the size of the HDL particles. According to the Δ(1–43)apoA-I crystal structure, H8 and H9 may form dimer interactions with H1 and the first A of H2. Unlike the five AB-repeating motifs that have a stringent dimerization structure, the N-terminal 43 residues, H1, and the first A unit of H2 together with the B-B-A-A-B motifs of H8, H9, and H10 in the C terminus may form different dimerization interfaces to accommodate different HDL disc size. The most recent simulation studies of discoidal HDL (48) also suggest that the N and C termini are more flexible with the “sticky” N terminus involved in interactions with the opposing N terminus or the backbone region. As shown in supplemental Fig S7, A and B, Δ(185–243)apoA-I can form different sizes of rHDL particles with POPC at an 80:1 ratio, although WT and plasma apoA-I can form major 9.6 nm rHDL particles.

We propose that the different sizes of discoidal HDL particles may be modeled as progressive polygons (hepta-, octa-, nona-, deca-, and hendecagon) with sides corresponding to the AB-repeating motifs as shown in Fig. 7B. The hinge region (Gly65, Pro66, Val67, and Thr68) is opened in the heptagon, octagon, and nonagon models. The larger decagon and hendecagon require the further unhinging at position (Ala37–Gln41) that leads to the possible partial dimerization of the N-terminal 43 residues. With dimerization interfaces similar to the Δ(1–43)apoA-I structure as the second smallest and our model from the Δ(185–243)apoA-I structure as the largest HDL particle, the diameters of the particles change from ∼7.3 to ∼12.4 nm corresponding to the five subclasses of rHDL: 7.8, 8.4, 9.6, 12.2, and 17.0 nm in diameter (49). Heptagon, octagon, nonagon, and hendecagon possibly resemble the 7.8, 8.4, 9.6, and 12.2 nm rHDL. Furthermore, the AB-repeating motifs may tilt at small angles ∼10° to the plane and further modify the size of the particle. This tilt can be identified in the crystal structures. MD simulation also suggests that apoA-I can assemble a range of dynamic lipoprotein particles, containing a continuously variable number of lipid molecules by the incremental twisting or untwisting of a saddle-shaped apoA-I double belt structure that creates minimal surface patches of lipid bilayer (48). This twisting or untwisting can be achieved by varying the tilt angles of each of the AB-repeating motifs by changing the proline kink angles.

LCAT Interaction and Central Tunnel in Helix 5

The central step of RCT is the activation of LCAT by apoA-I to esterify the cholesterol molecules in nascent, phospholipid-rich HDL into cholesterol ester resulting in spherical, cholesteryl ester-rich, mature HDL (2). Segment deletion (14), replacement with the sequence of the C-terminal segment (50), and reversal of the sequence (51) suggest that H6(AB4) is involved in LCAT activation. Mutations of Arg149, Arg153, and Arg160 in this region lead to loss of LCAT activity possibly through the disruption of salt bridge interactions between LCAT and apoA-I (52). Mutation E110A/E111A H4(AB2) has also been shown to affect LCAT activation (53). In the Δ(185–243)apoA-I structure the antiparallel interaction and intermolecular salt bridge stabilization (Glu111, His155, and Arg151) of these two segments would suggest that any disruption of the interaction through mutation of either segment would affect LCAT binding or activation. As shown in Fig. 3C, Glu110, Arg149, Arg153, and Arg160 are on the outside surface of the apoA-I dimer backbone and may form salt bridges with LCAT during the interaction. Thus, mutation of these charged amino acids can disrupt the interaction of apoA-I with LCAT. As shown in supplemental Fig S7C, POPC-cholesterol-Δ(185–243)apoA-I rHDL particles can activate LCAT and convert free cholesterol into cholesteryl ester similar to POPC-cholesterol-WT apoA-I rHDL particles. This suggests that the C-terminal domain of apoA-I (residues 185–243) is not required to activate LCAT.

Recent simulation studies have suggested that the central domains (H5/H5) in apoA-I may form an amphipathic presentation tunnel for migration of hydrophobic acyl chains and amphipathic cholesterol from the bilayer to the active site of LCAT (54). The simulation results predict that the solvent side surface of the tunnel is composed of Glu125, Lys133, Glu136, and Lys140. Among these, Lys133 and Lys140 may form intra-helical salt bridges with Glu136 and inter-helical salt bridges with Glu125, although the lipid side is covered by five Leu residues with the Ala130 residues lining the top and bottom of the tunnel and Glu129 on the solvent side (54). Our crystal structure clearly shows a central hole, ∼5 Å diameter, between the antiparallel H5 domains formed by the opposition of Ala130 as shown in Fig. 2. The surface clearly shows that the tunnel has a hydrophobic inside surface (Leu126, Leu137, and Ala130) and strongly charged outside surface (Glu125, Glu128, Lys133, and Glu136) as shown in Fig. 4B. Lys133, Glu136, and Lys140 formed intra-helical triad salt bridges as shown in Fig. 3A. Unlike other antiparallel pairs of AB units and the MD simulation results, there are no inter-helical salt bridges between the helices in this domain. Upon lipid binding, the rotation of the helix to face the leucines toward the lipid-binding surface may enlarge the tunnel and re-arrange the salt bridges. In addition, the flexibility and partial helical character of this region (residues 135–141) may contribute to the opening. Furthermore, this repeat contains the uniquely positioned Arg123 in the hydrophobic face. We suggest that this basic residue is poised for interaction with a fatty acid produced by LCAT hydrolysis of the sn-2 chain of a phospholipid.

Milano, Paris, and Fin Mutations

ApoA-IMilano (R173C) and apoA-IParis (R151C) are natural variants of apoA-I that manifest HDL deficiencies. The low levels of plasma HDL would suggest that carriers of the Milano and Paris mutation would be at high risk for atherosclerosis, but the contrary was reported (55). Other studies suggest that this anomaly results from antioxidant activity because of the incorporation of a free thiol (25). However, monomeric apoA-IMilano can be found on the surface of HDL3 ranging from 30 to 40% of the apoA-I mass (26), and for apoA-IParis ∼10% of the total plasma pool of apoA-I is monomeric (56). The monomeric form on HDL3 suggests that these mutations disrupt the dimerization ability of the apoA-I. As shown in Fig. 3B, in the crystal structure, Arg173 and Arg151 are key residues in the two intermolecular salt bridge networks that stabilize the five AB repeat backbone. The mutation of the Arg173 and Arg151 might cause the disruption of the inter-helical salt bridges Arg177–Asp89 and His155–Glu111 that determine the H5/H5 registration. In the Milano and Paris double belt model, different helix registration is proposed due to the formation of the disulfide bond between the cysteine residues with fewer or no inter-helical salt bridges (34). This decrease in inter-helical salt bridges might cause instability in the antiparallel double helix backbone thus leading to the monomeric form of the protein.

Family members with the apoA-IFin (L159R) mutation have reduced plasma HDL cholesterol (20%) and apoA-I (25%) compared with unaffected family members. Proteolytic degradation of apoA-IFin in plasma is thought to account for the low apoA-I concentrations (27). As shown in supplemental Fig. S8, Leu159 is situated in the middle of the N-terminal bundle near the residues involved in the formation of the aromatic cluster and the π-cation interaction in the hydrophobic core. Mutation of this Leu into a strongly charged Arg will disrupt the hydrophobic core, destroying the aromatic cluster and the π-cation interaction. The consequent disruption of the N-terminal helix bundle and its stabilizing role in the structure may render the lipid-free apoA-I accessible to the protease thus leading to degradation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Olga Gursky for advice with CD experiments and discussion, Cheryl England for providing the plasma apoA-I, and Dr. Qun Liu and Dr. John Schwandof at Brookhaven National Laboratory beamline X4C for excellent assistance. We thank Dr. Shobini Jayaraman for help making rHDL and LCAT activation assay, Donald Gantz for EM, and Michael Gigliotti for lipid TCL analysis. We thank Dr. Bob Sweet in Department of Biology, Brookhaven National Laboratory, for organizing Rapid Data 2010. We also thank Dr. James Head for advice for crystal structure refinement and Dr. G. Graham Shipley and Dr. Donald M. Small for reviewing the manuscript and valuable advice.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant P01-HL026335.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S8, Tables S1–S3, “Experimental Procedures,” and additional references.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3R2P) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- RCT

- reverse cholesterol transport

- apoA-I

- apolipoprotein A-I

- LCAT

- lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- TEV

- tobacco etch virus

- POPC

- 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- Se-Met

- selenomethionine

- rHDL

- reconstituted HDL.

REFERENCES

- 1. Heron M., Hoyert D. L., Murphy S. L., Xu J., Kochanek K. D., Tejada-Vera B. (2009) Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 57, 1–134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fielding C. J., Fielding P. E. (1995) J. Lipid Res. 36, 211–228 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fielding C. J., Shore V. G., Fielding P. E. (1972) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 46, 1493–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee J. Y., Parks J. S. (2005) Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 16, 19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Acton S., Rigotti A., Landschulz K. T., Xu S., Hobbs H. H., Krieger M. (1996) Science 271, 518–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marcel Y. L., Kiss R. S. (2003) Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 14, 151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andrews A. L., Atkinson D., Barratt M. D., Finer E. G., Hauser H., Henry R., Leslie R. B., Owens N. L., Phillips M. C., Robertson R. N. (1976) Eur. J. Biochem. 64, 549–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Segrest J. P., Jones M. K., De Loof H., Brouillette C. G., Venkatachalapathi Y. V., Anantharamaiah G. M. (1992) J. Lipid Res. 33, 141–166 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Segrest J. P., Jackson R. L., Morrisett J. D., Gotto A. M., Jr. (1974) FEBS Lett. 38, 247–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nolte R. T., Atkinson D. (1992) Biophys. J. 63, 1221–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Okon M., Frank P. G., Marcel Y. L., Cushley R. J. (2001) FEBS Lett. 487, 390–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Okon M., Frank P. G., Marcel Y. L., Cushley R. J. (2002) FEBS Lett. 517, 139–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chetty P. S., Mayne L., Lund-Katz S., Stranz D., Englander S. W., Phillips M. C. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 19005–19010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sorci-Thomas M., Kearns M. W., Lee J. P. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 21403–21409 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laccotripe M., Makrides S. C., Jonas A., Zannis V. I. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 17511–17522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rogers D. P., Roberts L. M., Lebowitz J., Datta G., Anantharamaiah G. M., Engler J. A., Brouillette C. G. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 11714–11725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gorshkova I. N., Liadaki K., Gursky O., Atkinson D., Zannis V. I. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 15910–15919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gorshkova I. N., Liu T., Zannis V. I., Atkinson D. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 10529–10539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fang Y., Gursky O., Atkinson D. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 6881–6890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fang Y., Gursky O., Atkinson D. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 13260–13268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saito H., Dhanasekaran P., Nguyen D., Holvoet P., Lund-Katz S., Phillips M. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23227–23232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gorshkova I. N., Liu T., Kan H. Y., Chroni A., Zannis V. I., Atkinson D. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 1242–1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gursky O., Atkinson D. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 2991–2995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Borhani D. W., Rogers D. P., Engler J. A., Brouillette C. G. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 12291–12296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bielicki J. K., Oda M. N. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 2089–2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Franceschini G., Frosi T. G., Manzoni C., Gianfranceschi G., Sirtori C. R. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 9926–9930 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McManus D. C., Scott B. R., Franklin V., Sparks D. L., Marcel Y. L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 21292–21302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nallamsetty S., Waugh D. S. (2007) Nat. Protoc 2, 383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Otwinowski Z., Minor W., Charles W., Carter (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H. (2010) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Painter J., Merritt E. A. (2006) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 39, 109–111 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) J. Comput Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fiser A., Do R. K., Sali A. (2000) Protein Sci. 9, 1753–1773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Klon A. E., Segrest J. P., Harvey S. C. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 10895–10905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gallivan J. P., Dougherty D. A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 9459–9464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marqusee S., Baldwin R. L. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 8898–8902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Olson C. A., Spek E. J., Shi Z., Vologodskii A., Kallenbach N. R. (2001) Proteins 44, 123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Davidson W. S., Hilliard G. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27199–27207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Silva R. A., Huang R., Morris J., Fang J., Gracheva E. O., Ren G., Kontush A., Jerome W. G., Rye K. A., Davidson W. S. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12176–12181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bhat S., Sorci-Thomas M. G., Tuladhar R., Samuel M. P., Thomas M. J. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 7811–7821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Silva R. A., Hilliard G. M., Li L., Segrest J. P., Davidson W. S. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 8600–8607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Davidson W. S., Silva R. A. (2005) Curr. Opin Lipidol. 16, 295–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bhat S., Sorci-Thomas M. G., Alexander E. T., Samuel M. P., Thomas M. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33015–33025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Segrest J. P., Jones M. K., Klon A. E., Sheldahl C. J., Hellinger M., De Loof H., Harvey S. C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 31755–31758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Catte A., Patterson J. C., Bashtovyy D., Jones M. K., Gu F., Li L., Rampioni A., Sengupta D., Vuorela T., Niemelä P., Karttunen M., Marrink S. J., Vattulainen I., Segrest J. P. (2008) Biophys. J. 94, 2306–2319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bashtovyy D., Jones M. K., Anantharamaiah G. M., Segrest J. P. (2011) J. Lipid Res. 52, 435–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jones M. K., Catte A., Patterson J. C., Gu F., Chen J., Li L., Segrest J. P. (2009) Biophys. J. 96, 354–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gu F., Jones M. K., Chen J., Patterson J. C., Catte A., Jerome W. G., Li L., Segrest J. P. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4652–4665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cavigiolio G., Shao B., Geier E. G., Ren G., Heinecke J. W., Oda M. N. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 4770–4779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sorci-Thomas M. G., Curtiss L., Parks J. S., Thomas M. J., Kearns M. W. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 7278–7284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sorci-Thomas M. G., Curtiss L., Parks J. S., Thomas M. J., Kearns M. W., Landrum M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 11776–11782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Roosbeek S., Vanloo B., Duverger N., Caster H., Breyne J., De Beun I., Patel H., Vandekerckhove J., Shoulders C., Rosseneu M., Peelman F. (2001) J. Lipid Res. 42, 31–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chroni A., Kan H. Y., Kypreos K. E., Gorshkova I. N., Shkodrani A., Zannis V. I. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 10442–10457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jones M. K., Catte A., Li L., Segrest J. P. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 11196–11210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sirtori C. R., Calabresi L., Franceschini G., Baldassarre D., Amato M., Johansson J., Salvetti M., Monteduro C., Zulli R., Muiesan M. L., Agabiti-Rosei E. (2001) Circulation 103, 1949–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Perez-Mendez O., Bruckert E., Franceschini G., Duhal N., Lacroix B., Bonte J. P., Sirtori C., Fruchart J. C., Turpin G., Luc G. (2000) Atherosclerosis 148, 317–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.