Background: Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling is a major target in anti-angiogenic therapies.

Results: Calcium (Ca2+) influx through reverse mode Na+/Ca2+ exchange (NCX) is required for VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation through the PKCα-B-Raf pathway.

Conclusion: Reverse mode NCX regulates endothelial cell (EC) responses to VEGF and thus angiogenic functions.

Significance: This identifies a novel biological mechanism in ECs, potentially providing new strategies for targeting misregulated angiogenesis.

Keywords: Calcium, Endothelium, ERK, Protein Kinase C (PKC), Sodium Calcium Exchange, Angiogenesis, VEGF

Abstract

VEGF is a key angiogenic cytokine and a major target in anti-angiogenic therapeutic strategies. In endothelial cells (ECs), VEGF binds VEGF receptors and activates ERK1/2 through the phospholipase γ (PLCγ)-PKCα-B-Raf pathway. Our previous work suggested that influx of extracellular Ca2+ is required for VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation, and we hypothesized that this could occur through reverse mode (Ca2+ in and Na+ out) Na+-Ca2+ exchange (NCX). However, the role of NCX activity in VEGF signaling and angiogenic functions of ECs had not previously been described. Here, using human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs), we report that extracellular Ca2+ is required for VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation and that release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores alone, in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, is not sufficient to activate ERK1/2. Furthermore, inhibitors of reverse mode NCX suppressed the VEGF-induced activation of ERK1/2 in a time- and dose-dependent manner and attenuated VEGF-induced Ca2+ transients. Knockdown of NCX1 (the main NCX isoform in HUVECs) by siRNA confirmed the pharmacological data. A panel of NCX inhibitors also significantly reduced VEGF-induced B-Raf activity and inhibited PKCα translocation to the plasma membrane and total PKC activity in situ. Finally, NCX inhibitors reduced VEGF-induced HUVEC proliferation, migration, and tubular differentiation in surrogate angiogenesis functional assays in vitro. We propose that Ca2+ influx through reverse mode NCX is required for the activation and the targeting of PKCα to the plasma membrane, an essential step for VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation and downstream EC functions in angiogenesis.

Introduction

Angiogenesis, the generation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vasculature, is central in physiological processes including embryonic development and the female reproductive cycle (1, 2). Unregulated angiogenesis plays a crucial role in the progression of pathophysiological conditions such as diabetic retinopathies, atherosclerosis, and aggressive tumor growth (1, 2).

VEGF is indispensable for endothelial cell (EC)3 maintenance under physiological conditions, and abnormal VEGF signaling has also been implicated in the anarchic angiogenesis that is the hallmark of numerous diseases (3). In the adult, ligation of VEGF to its primary receptor VEGFR2 (Flk1/KDR) results in a complex response, involving the activation of phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1), Src kinase, and PI3K (3–5). Ultimately, this primes the endothelium for angiogenesis through the mobilization of downstream effectors such as endothelial nitric-oxide synthase, PKC, MAPKs, and the transient increase of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) (3). Given the importance of VEGF signaling in pathophysiological angiogenesis, it is not surprising that more than 20 reagents targeting the VEGF pathway are currently being evaluated for the management of aggressive tumor growth (6), and anti-VEGF therapy is successfully being used for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration (7) and some cancers (8). Despite the enormous progress made in the study of angiogenesis over the last 20 years, therapeutic outcomes, particularly in the oncology field, remain variable and often transient (9, 10). Consequently, there is an urgent need to further characterize the complex biological response of ECs to VEGF.

The Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) is a plasma membrane protein ubiquitously expressed in mammalian cells (11, 12). The exchanger can extrude Ca2+ from cytosol in exchange for Na+ (forward-mode) or work in reverse mode (Ca2+ in and Na+ out) depending on the transmembrane concentration gradients for Ca2+ and Na+ and the membrane potential (11, 12). There are three mammalian NCX isoforms (NCX1–NCX3) that are products of separate genes. NCX is a low Ca2+ affinity, high capacity transporter. Based on measurements of ionic fluxes, intracellular Na+ and/or Ca2+ concentrations, and the reversal potential of the Na+-Ca2+ current, it is widely accepted that NCX exchanges three Na+ for one Ca2+ across the plasma membrane (13–15), although different coupling ratios have also been reported (16). The primary physiological function of the NCX is to extrude Ca2+ during excitation-contraction coupling on a beat-to-beat basis in the heart (11). NCX is also expressed in a number of nonexcitable cells including vascular smooth muscle, glia, kidney, and adrenal chromaffin cells (11). Endothelial cells have also been shown to express the cardiac NCX1 isoform (17–20) and in particular the spliced variants NCX1.3 and NCX1.7 (21). In the endothelium, the role of NCX activity in cell signaling has not been studied extensively, although limited studies have implicated Ca2+ entry through reverse mode NCX in the activation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (22).

In a recent study, we reported that voltage-gated Na+ channels (VGSCs) are involved in VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation through the modulation of membrane potential (Vm) and subsequent PKCα activity. We proposed that this could occur through inhibition of reverse mode NCX activity and diminished Ca2+ entry (23). Although NCX has been shown to be capable of operating in reverse mode (24) and to have significant impact on EC functions such as NO production or Ca2+ influx in “classic” Ca2+ readdition protocols in HUVECs (22), the role of NCX activity in VEGF signaling and angiogenic functions has not been previously studied. In the present study, we investigated whether influx of extracellular Ca2+ is required for VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation and the role of reverse mode NCX activity in this process.

We report that extracellular Ca2+ is indeed required for VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation and that release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores alone, in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, is not sufficient to trigger ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Moreover, VEGF-induced Ca2+ transients and ERK1/2 activation were attenuated by a panel of reverse mode NCX inhibitors, and VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation was suppressed by reducing NCX1 protein expression with siRNA. Furthermore, inhibition of the Na+/K+-ATPase with ouabain, a treatment that would favor reverse mode NCX activity, augmented VEGF-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. In addition, reverse mode NCX inhibitors suppressed total PKC activity in response to VEGF in situ and the translocation of PKCα to the plasma membrane. Finally, we report that inhibition of reverse mode NCX attenuated VEGF-induced HUVEC proliferation, chemotactic migration, and tubular differentiation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Thapsigargin, SN-6, and KBR-7943 were purchased from Tocris. 3′,4′-Dichlorobenzamil (DCB), VEGF-A (VEGF hereafter), amiloride, and nifedipine were purchased from Sigma. SEA0400 was synthesized by Taisho Pharmaceutical (Saitama, Japan). The suppliers of all other reagents are indicated in the text. HUVECs were from pooled donors (TCS Cellworks, Buckingham, UK) and were cultured according to the supplier's instructions.

Cell Culture and Protein Extraction

HUVECs were maintained in large vessel EC growth medium with the addition of endothelial growth supplements (TCS Cellworks) and grown as described previously (23). For the VEGF stimulation assays, the cells were washed twice with PBS and then serum-starved for 1 h in a serum-free physiological buffer containing 144 mm NaCl, 5.4 mm KCl, 2.5 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 5.6 mm d-glucose, and 5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, at 37 °C. Inhibitors or control vehicle were added 30 min before the beginning of each experiment. The cells were activated by the addition of 50 ng/ml VEGF, maintained for the indicated times at 37 °C, and the reaction was terminated by washing the cells once with ice-cold PBS, placing them on ice, and immediately applying cold lysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% v/v Triton X-100, 0.5 mm DTT, 1 mm PMSF, 1% v/v protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), 1 mm NaF, 5 mm bpVphen (Calbiochem), 5 μm fenvalerate (Calbiochem), 1 mm Na3VO4, and 1% v/v phosphatase inhibitor cocktails I and III (Sigma). The cell homogenate was incubated for 10 min on ice and then centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until further use. Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Sigma), with BSA (Sigma) as the protein standard. HUVECs were used between passages 3 and 9.

Western Blots

Western blotting was performed as previously described (23), using the NuPAGE electrophoresis system (Invitrogen). Protein bands were visualized using the ECLplus chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham Biosciences). The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-phospho-p44/p42 ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204), rabbit anti-p44/p42 (total-ERK), rabbit anti-phospho-PLCγ1 (Tyr-783) and peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, from Cell Signaling. Mouse anti-PLCγ1, mouse anti-B-Raf, and mouse anti-PKCα were from Santa Cruz. The mouse anti-NCX1 was from Swant, and the mouse anti-GAPDH was from Abcam Labs. Films were scanned, and the optical densities of bands of interest were determined using Gel-Pro Analyzer 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics). The optical density of phospho-proteins was normalized against the corresponding protein loading controls. The ratio of phospho/total protein of the unstimulated controls in each experiment was arbitrarily set as 1. The values of the experimental conditions are represented as fold × normalized unstimulated controls from at least three independent experiments.

Gene Silencing

siRNA was used to knockdown the expression of NCX1, the predominant NCX isoform in HUVECs (21). The siRNA duplexes (siGENOME SMARTpool) (Dharmacon) had the following accession numbers: NM_001112800, NM_001112801, NM_ 01112802, and NM_021097; nontargeting siRNA pool was the control. Transfections were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions, essentially as detailed previously (23). Briefly, subconfluent cultures (∼40–50%, 2 × 105 cells) were transfected at 37 °C with siRNA using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). The final concentration of siRNA was 100 nm in OPTIMEM (Invitrogen), and transfections were carried out for 4 h at 37 °C and terminated by the addition of two volumes of endothelial complete medium (TCS Cellworks). Transfected HUVECs were maintained for 48 h prior to any further treatment.

B-Raf Activity Assay

The B-Raf activity assay was carried out essentially as described in detail previously (23) using the B-Raf kinase cascade kit (Upstate). At the end of the assay, the beads with immunoprecipitated B-Raf from each experimental condition were heated for 5 min at 95 °C with 1× loading buffer and subjected to Western blot to ensure equal amounts of B-Raf in each experimental condition.

Total PKC Activity Assay

PKC activity was determined according to the method of Heasley and Johnson (25), as modified by Xia et al. (26). HUVECs in 24-well plates (∼2 × 104 cells) were incubated for 1 h in serum-free buffer. Inhibitors or vehicle were applied 30 min before the addition of 50 ng/ml VEGF. After 10 min of VEGF stimulation, the medium was aspirated, and the cells were placed in 60 μl of serum-free buffer supplemented with 50 μg/ml digitonin (Sigma), 5 mm EGTA, 25 mm β-glycerolphosphate (Calbiochem), 7.5 mm MgCl2, 100 μm ATP, 1 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer Life Sciences; specific activity, 3000 Ci/mmol), and 100 μm of PKC-specific peptide substrate (Calbiochem) corresponding to the 4–14 amino acids of myelin basic protein. The reaction proceeded for 10 min at 37 °C and was terminated by the addition of 25 μl of 25% (w/v) ice-cold TCA (Sigma). 60 μl of the reaction mixture were spotted on P81 phosphocellulose filters (Millipore). The filters were washed three times for 10 min in 75 mm H3PO4, and the peptide-associated 32P radioactivity bound to the filters was quantified by scintillation counting, with Optima GoldTM (Perkin Elmer) as the scintillant. Specific PKC activity was determined by subtracting the counts per min obtained from VEGF-stimulated cells pretreated with 5 μm of the PKC inhibitor GF109203X (GFX; Calbiochem) for 30 min and then treated as normal.

PKCα Translocation Assay

PKCα translocation to the plasma membrane was determined as described previously (23, 26). Serum-starved HUVECs (∼1 × 106 cells) in serum-free medium were stimulated with 50 ng/ml VEGF in the presence of various concentrations of NCX inhibitors for 10 min. The cells were suspended in 1 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer without detergents, homogenized by passing 20 times through a 21-gauge needle, sonicated three times for 20 s with 1-min intervals on ice, and finally centrifuged for 10 min at 5000 × g. The cleared supernatant was diluted with lysis buffer to 4 ml and ultracentrifuged for 1 h at 100,000 × gav in a Ti-32 rotor (Beckman). The supernatant was collected as the cytosolic fraction, and the membrane fraction was resuspended in 1× Western blot loading buffer and heated for 10 min at 95 °C. PKCα translocation to the membrane fraction was then determined by Western blot.

[Ca2+]i Measurement

Measurements of [Ca2+]i were carried out according to our previously published method (23). Serum-starved HUVECs (1 × 104 cells/well), attached to a sterile flat clear-bottomed black-walled 96-well microtitre plate (Corning) were washed twice with PBS and loaded with the Ca2+ dye indicator Fluo-4NW (Invitrogen) for 45 min at 37 °C in the dark. The Fluo-4NW solution was freshly prepared prior to each experiment by adding 10 ml of Hanks' balanced salt solution (Invitrogen), supplemented with 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, and 100 μl of 250 mm probenicid stock solution (Component B; Molecular Devices), to one bottle of Component A (Fluo-4NW dye mix; Molecular Devices).

Following the incubation period, equal volumes of Hanks' balanced salt solution containing the appropriate concentrations of inhibitors or vehicle were added, and the cells were incubated for a further 15 min. The plate was then transferred in the assay chamber of a FLIPR plate reader (Molecular Devices), and HUVECs were challenged with 50 ng/ml VEGF in Hanks' balanced salt solution for 400 s at 37 °C. The [Ca2+]i was monitored immediately after the addition of stimulant, as a measure of changes in fluorescence intensity at 37 °C on a FLIPR (Molecular Devices) with excitation of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 525 nm (cut-off, 515 nm). The data points were acquired every 2 s. Typically, immediately before the assay, an end point fluorescent reading with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 525 nm, respectively, was obtained to ensure uniform dye loading of all the sample wells. Background fluorescence was measured for 20 s prior to the addition of stimulant, and the results are presented as a ratio of sample fluorescence at any given time point divided by background fluorescence. All of the experimental conditions were in triplicate and were assayed simultaneously.

Transwell Migration Assay

The migration assay was as described previously (23, 27). Briefly, serum-starved HUVECs, labeled for 1 h with 1 μm CellTracker green 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate (Molecular Probes) were placed into the upper chambers of a 3-μm pore FluoroblokTM insert (Becton Dickinson Biosciences) containing 350 μl of serum-free medium with inhibitors or vehicle. The inserts were precoated on both sides with 50 μg/ml collagen I for 2 h. Approximately 3 × 104 cells were plated onto each filter. After adding 800 μl of MCDB-131 medium containing 50 ng/ml VEGF-A (Sigma), the assay plates were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 16 h. Basal HUVEC migration was assessed by seeding 3 × 104 HUVECs in the upper chamber without adding the chemoattractant (VEGF-A) in the lower chamber and was subtracted from the number of the migrating cells in the presence of VEGF-A. Images of the migrated cells in the lower chamber were obtained with an inverted fluorescent microscope at 10× magnification (Olympus LX70, Middlesex, UK) and a digital camera (cool SNAP pro-color; Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD). Typically, images were acquired from five randomly chosen fields of view. The numbers of migrated cells were counted using Image Pro-Plus 5.0 software (Media Cybernetics). The data were expressed as percentage migration relative to untreated (control) cells.

Tubulogenesis Assay

The assay was carried out essentially as described previously (23, 28). Briefly, the cells were plated at a density of 3 × 104 cells/well in 24-well plates precoated with 300 μl of Matrigel (Becton Dickinson Biosciences) in complete HUVEC medium, with or without NCX inhibitors. The cells were incubated for periods of 4 h before images were obtained and quantified for tubular length using Image Pro-Plus 5.0 software.

Proliferation Assay

3 × 103 HUVECs/well were seeded into 96-well plates (Nunc) precoated with 50 μg/ml collagen I for 2 h, in complete EC medium. The following day, the medium was aspirated, and 100 μl of MCDB-131 medium containing 0.1% (w/v) BSA and 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone was added. Where appropriate, the medium contained 50 ng/ml VEGF and different concentrations of NCX inhibitors or vehicle. Each condition was tested in triplicate. After incubation for 48 h at 37 °C in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in air, the relative number of cells in each well was determined by the alkaline phosphatase assay as described previously (23).

Data Analysis

The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. of the mean. Where applicable, statistical significance was determined by the Student's paired, one-tailed t test. The values of p < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

Extracellular Ca2+ and Na+ Are Required for VEGF-induced ERK1/2 Phosphorylation

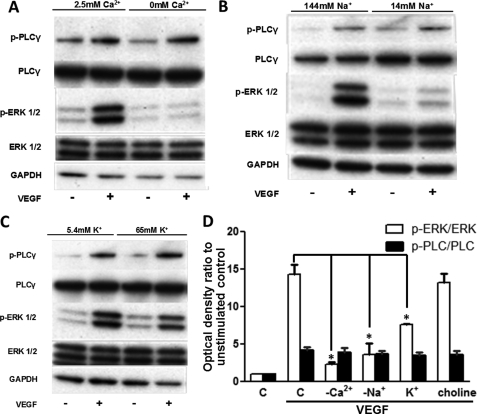

HUVECs were exposed to 50 ng/ml VEGF for 10 min in a nominal Ca2+-free medium (Ca2+ was omitted), a low Na+ medium (extracellular Na+ concentration was reduced 10-fold by choline chloride substitution), and a high K+ medium (65 mm K+ was added). By omitting Ca2+ from the extracellular buffer, the increase in phospho-ERK1/2 levels upon VEGF stimulation (14.2 ± 1.2-fold versus unstimulated control) as determined by densitometry of Western blots was significantly inhibited (2.22 ± 0.33-fold, p = 0.004, n = 3; Fig. 1, A and D). Isotonically decreasing [Na+] from the extracellular buffer also resulted in a pronounced reduction of the phospho-ERK1/2 levels when the cells were stimulated with VEGF (14.1 ± 0.8-fold down to 3.58 ± 1.44, p = 0.01, n = 3; Fig. 1, B and 1D). Similarly, depolarizing the cell membranes by adding 65 mm K+ also caused a significant reduction of ERK1/2 activity (13.2 ± 0.6-fold down to 7.59 ± 0.1, p = 0.005, n = 3; Fig. 1, C and D), presumably by decreasing the influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular space (22). As a control for the latter treatment, [Na+]o was reduced by the same amount (65 mm); this noticeably decreased ERK1/2 phosphorylation (not shown), consistent with the result of the second experiment. However, increasing the osmolarity of the medium to a similar extent by the addition of 65 mm choline chloride had no significant effect on VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 1D and supplemental Fig. S1). The controls confirmed that the effect of applying high K+ was not due to a change of osmolarity but more likely due to decreased passive influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular medium (22). Under all of these ionic conditions, phospho-PLCγ levels were not significantly altered in the VEGF-stimulated cells (Fig. 1D), indicating that the extracellular ions had no effect on VEGFR-2 activity and that the samples were equally stimulated (4, 23).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of ionic substitutions on phospho-ERK1/2. A–C, HUVECs were serum-starved in complete physiological medium for 45 min, the medium was aspirated, and the cells were incubated for 15 min in media with the following ionic substitutions: Ca2+ omitted from the buffer (A), Na+ ions isotonically substituted with choline chloride to 14 mm (B), and buffer contains 65 mm K+ (C). HUVECs were stimulated with 50 ng/ml VEGF for 10 min. ERK1/2 and PLCγ activation was determined by Western blot. Total ERK1/2 and GAPDH protein levels were used to demonstrate protein loading. Representative immunoblots are shown (n = 3). D, optical densities of the p-ERK1/2 and p-PLCγ bands in A–C and supplemental Fig. S1 were determined and normalized against the corresponding total protein loading controls. The normalized optical density of the unstimulated control (bar C) sample for each experiment is arbitrarily set to 1. The mean value of the ratio for each condition is expressed as fold × unstimulated control value. The bars represent the means ± S.E. from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus the VEGF stimulated control.

Influx of Extracellular Ca2+ Rather than Ca2+ Release from Internal Stores Is Crucial for VEGF-induced ERK1/2 Phosphorylation

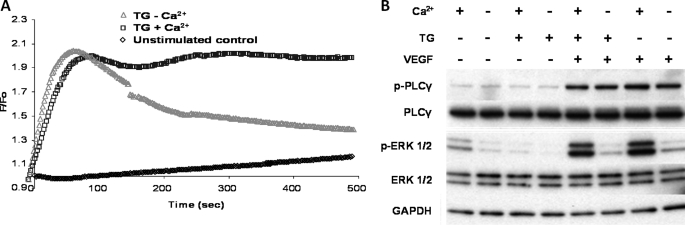

HUVECs were treated with the inhibitor of the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase thapsigargin (TG; 4 μm) (29) for 2 min prior to VEGF stimulation (50 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of extracellular Ca2+. Application of TG resulted in a rapid and robust increase of [Ca2+]i in the presence of extracellular Ca2+. The Ca2+ response peaked within 2 min and remained at this level for the duration of the experiment (500 s; Fig. 2A). In contrast, when TG was applied in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, although the initial response was similar to the TG + Ca2+ condition, the tonic (sustained) component of the Ca2+ transient decayed toward the level of the unstimulated control (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Role of extracellular Ca2+ as opposed to Ca2+ release from internal stores in ERK1/2 phosphorylation. A, representative time courses of Ca2+- sensitive Fluo-4NW fluorescence recorded during TG stimulation of HUVECs. Serum-starved HUVECs were stimulated with TG (4 μm) at time 0 in the presence (blue squares) or absence (red triangles) of extracellular Ca2+. The unstimulated control (black diamonds) is also shown. Fluorescence intensity was measured every 2 s at 37 °C on a FLIPR plate reader (Molecular Devices) with excitation of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 525 nm. n = 3 in triplicate. B, HUVECs were serum-starved in a complete physiological medium for 45 min, the medium was aspirated, and the cells were incubated for a further 15 min in a medium where Ca2+ was omitted as indicated. HUVECs were then stimulated with 4 μm TG for 2 min. Subsequently, where indicated, 50 ng/ml VEGF was applied for 10 min. ERK1/2 and PLCγ activation was probed as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Representative immunoblots are shown (n = 3).

Next, we tested the effects of TG and TG + VEGF, on ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the presence or absence of extracellular Ca2+. TG itself had no effect on the levels of phospho-ERK1/2 or phospho-PLCγ, irrespective of the presence of Ca2+ in the extracellular medium (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, when VEGF (50 ng/ml) was added 2 min after the application of TG at the peak of the Ca2+ response (Fig. 2A), no appreciable ERK1/2 phosphorylation could be detected in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 2B) As shown in Fig. 1A, extracellular Ca2+ was required for VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2B). Additionally, extracellular Ca2+ did not affect phospho-PLCγ levels. In conclusion, influx of extracellular Ca2+ (the later phase of the [Ca2+]i transient), rather than release of Ca2+ from the internal stores (the early phase), was essential for ERK1/2 phosphorylation by VEGF.

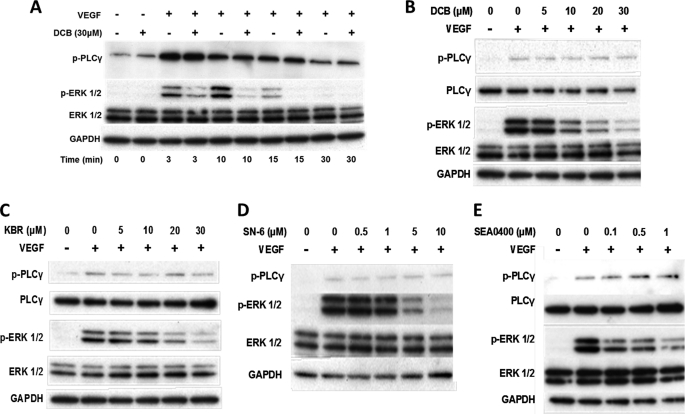

Reverse Mode NCX Inhibitors Attenuated VEGF-induced ERK1/2 Phosphorylation

ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the presence of the NCX inhibitor DCB (30) was studied using an antibody that specifically recognizes p-ERK1/2. Stimulation of serum-starved HUVECs with 50 ng/ml VEGF resulted in a marked increase in the levels of p-ERK1/2, peaking between 3 and 10 min and returning to basal levels after 30 min, as previously reported (23). Preincubation of HUVECs with 30 μm DCB for 30 min reduced the phospho-ERK1/2 levels in comparison with the vehicle-treated control (0.5% v/v Me2SO; Fig. 3A). On the other hand, p-PLCγ levels, at each time point analyzed, were not apparently affected by DCB treatment (Fig. 3A, top panel). DCB also inhibited VEGF-induced activation of ERK1/2 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3B and supplemental Fig. S2). To exclude any nonspecific effects of DCB attributed to its chemical similarities to amiloride, HUVECs were pretreated with various concentrations of amiloride, challenged with VEGF and ERK1/2 activation assayed by Western blot. Amiloride (up to 30 μm) had no apparent effect on VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in comparison with the untreated control (supplemental Fig. S3).

FIGURE 3.

Effect of NCX inhibitors on VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. A, serum-starved HUVECs were preincubated (for 30 min) with 30 μm DCB or vehicle (0.5% v/v Me2SO) prior to VEGF stimulation (50 ng/ml) for the times indicated. B, ERK1/2 and PLCγ activation was analyzed by Western blot as described in Fig. 1. The effect of DCB was also dose-dependent. C–E, serum-starved HUVECs were preincubated for 30 min with various concentrations of the reverse mode Na+-Ca2+ exchanger inhibitors KBR-7943 (C), SN-6 (D), or SEA0400 (E) prior to stimulation with VEGF (50 ng/ml) for 10 min. ERK1/2 and PLCγ phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blot. Representative immunoblots are shown (n = 3).

HUVECs were pretreated with the reverse mode NCX inhibitors KBR-7943 (KBR; Fig. 3C) (31), SN-6 (Fig. 3D) (32), or SEA0400 (Fig. 3E) (33), at concentrations reported to be selective for reverse mode NCX (34), for 30 min prior to stimulation with VEGF. All three inhibitors attenuated VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3, C–E, and supplemental Fig. S4–S6) without any significant effect on phospho-PLCγ (supplemental Fig. S4–S6). The effect of KBR and SEA0400 was also time-dependent (supplemental Figs. S7 and S8, respectively). Additionally, in the case of KBR, at all of the time points tested, phospho-PLCγ levels were not detectably affected by KBR treatment (supplemental Fig. S7). We concluded that (i) VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation involves reverse mode NCX activity, (ii) based on the lack of effect on PLCγ phosphorylation, reverse mode NCX activity did not directly influence VEGFR-2 activity (4, 23), and (iii) the samples were equally stimulated. Thus, our original hypothesis was supported by the use of pharmacological inhibitors.

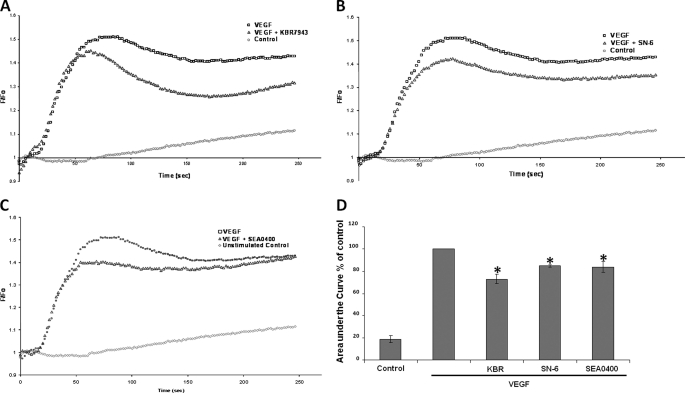

Inhibitors of Reverse Mode NCX Diminished the VEGF-induced [Ca2+]i Response

The effects of the same panel of NCX inhibitors (KBR-7943, SN-6, and SEA0400) on VEGF-induced Ca2+ transients were then investigated. VEGF stimulation of serum-starved HUVECs resulted in a rapid increase in fluorescence that peaked at ∼60 s. Bulk cytosolic Ca2+ levels remained significantly higher than the baseline for the duration of the experiment (5 min). Preincubation of the HUVECs for 15 min with the reverse mode NCX inhibitors KBR7943 (10 μm), SN-6 (10 μm), or SEA0400 (1 μm), prior to VEGF stimulation, resulted in a partial decrease in the initial phase of the Ca2+ response (Fig. 4, A–C, respectively) with a protracted suppression of the subsequent tonic Ca2+ response. Thus, KBR7943 (10 μm), SN-6 (10 μm), and SEA0400 (1 μm) suppressed the Ca2+ response, quantified as area under the curve, by 26.9 ± 3.9%, p = 0.01; 15.1 ± 1.1%, p = 0.003; and 16.2 ± 5.0%, p = 0.04, respectively, in comparison with the VEGF-stimulated control (arbitrarily set to 100%) (Fig. 4D). In all experimental conditions, n = 3 in triplicate.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of reverse mode NCX inhibitors on Ca2+ transients. Representative time courses of Ca2+-sensitive Fluo-4NW fluorescence recorded during VEGF stimulation of HUVECs are shown. Serum-starved HUVECs were stimulated with VEGF (50 ng/ml) at time 0. A–C, the following traces are shown: unstimulated control (red circles), VEGF-stimulated control (black squares), 20 min of preincubation with 10 μm KBR7943 (A), 20 min of preincubation with 10 μm SN-6 (B), 20 min of preincubation with 1 μm SEA0400 prior to VEGF stimulation (blue triangles) (C). Fluorescence intensity was measured every 2 s at 37 °C on a FLIPR plate reader (Molecular Devices) with excitation of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 525 nm (n = 3 in triplicate). D, the area under the curve of the Ca2+ trace was calculated for each condition. The area under the curve of the VEGF-stimulated control was set to 100%. The bars represent the means ± S.E. (n = 3 in triplicate). *, p < 0.05 versus VEGF-stimulated control.

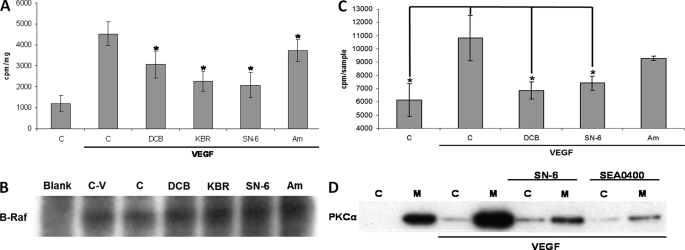

Reverse Mode NCX Inhibitors Attenuated VEGF-induced B-Raf, Total PKC Activities, and PKCα Translocation to the Plasma Membrane

VEGF is known to activate ERK1/2 in ECs through a pathway that involves PLCγ, PKC, and B-Raf, in a manner reported to be independent of Ras (35, 36). We have recently shown that tetrodotoxin, a VGSC inhibitor, decreases VEGF-induced B-Raf activity (23). Thus, we investigated whether inhibiting NCX activity would influence ERK1/2 phosphorylation by reducing B-Raf activity. VEGF stimulation of serum-starved HUVECs for 10 min resulted in an ∼4-fold increase in B-Raf activity in comparison with the vehicle-treated control (1195 ± 373 and 4534 ± 567 cpm/mg, respectively; n = 4 for both; Fig. 5A). Preincubation of HUVECs for 30 min with 30 μm DCB, 20 μm KBR, or 10 μm SN-6 resulted in significant decreases to the incorporated radioactivity to the substrate of the kinase assay (3068 ± 635 cpm/mg, p = 0.005; 2266 ± 468 cpm/mg, p < 0.001; and 2074 ± 613 cpm/mg, p < 0.001, respectively, n = 4 in all cases) in comparison with the vehicle treated control (0.5% v/v Me2SO, 4534 ± 567 cpm/mg, n = 4). Amiloride (30 μm), used as a negative control of DCB, had a much less pronounced effect on B-Raf activity (3728 ± 529 cpm/mg, p = 0.001, n = 4). To ensure equal B-Raf immunoprecipitation, subsequent to the activity assay, the amount of B-Raf protein associated with the beads corresponding to each sample was assessed by Western blot (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of NCX inhibitors on B-Raf and PKC activity. A, serum-starved HUVECs were preincubated for 30 min with 30 μm DCB, 20 μm KBR, 10 μm SN-6, or 30 μm amiloride (Am) as a negative control or vehicle (0.5% v/v Me2SO) prior to VEGF (50 ng/ml) stimulation for 10 min. B-Raf was immunoprecipitated overnight from total cell extracts. Subsequently, B-Raf activity was assayed using an immunoprecipitation kinase cascade kit (Upstate) by determining radioactivity incorporated into the substrate (myelin basic protein) by scintillation counting. Specific B-Raf activity was determined by subtracting the background radioactivity in a control sample (Blank) containing no anti-B-Raf Ab. The bars represent mean counts per min per milligram of input protein per sample ± S.E. from four independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus the VEGF-stimulated control. B, B-Raf immunoprecipitation equivalence in different samples was assessed by Western blot. Sample abbreviations are as in A; the control sample with no anti-B-Raf antibody (Blank) is also included. A representative immunoblot is shown (n = 2). C, serum-starved HUVECs were pretreated with vehicle (bar C) (0.5% v/v Me2SO), 30 μm DCB, 10 μm SN-6, or amiloride (Am) (30 μm) for 30 min and stimulated with VEGF (50 ng/ml) for 10 min. PKC activity, in situ, was determined by measuring the radioactivity incorporated into a PKC peptide substrate with scintillation counting as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The bars represent mean counts per sample ± S.E. from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus the VEGF-stimulated control. D, serum-starved HUVECs were incubated for 30 min with 10 μm SN-6 or 1 μm SEA0400 prior to stimulation with VEGF (50 ng/ml) for 10 min. Subsequently, the cells were lysed in a detergent-free buffer and ultracentrifuged for 1 h (105 × gav). The supernatant was collected as the cytosolic fraction (lanes C), and the pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (membrane fraction, lanes M). PKCα distribution to each fraction was determined by Western blot and subsequent probing with an anti-PKCα monoclonal antibody. A representative immunoblot from three independent repeats is shown.

The possibility that the observed reduction in B-Raf activity by NCX inhibition was due to a decrease in PKC activity was investigated. VEGF stimulation of serum-starved HUVECs for 10 min resulted in an ∼2-fold increase in the incorporated radioactivity to the peptide pseudo-substrate in comparison to the untreated control (6136 ± 1244 and 10885 ± 1720 cpm, p = 0.01, n = 3, respectively; Fig. 5C). Preincubation of HUVECs with 30 μm DCB or 10 μm SN-6 resulted in a significant decrease in the incorporated radioactivity to the substrate (6852 ± 633 cpm, p = 0.04; 7414 ± 548 cpm, p = 0.042, respectively; n = 3 in both cases) in comparison with the vehicle-treated control (0.5% v/v Me2SO). Amiloride (30 μm) was associated with a reduction in PKC activity, but this was not statistically significantly different from stimulated controls (9304 ± 157 cpm, p = 0.28, n = 3).

The effect of the reverse mode NCX inhibitors SN-6 and SEA0400 on VEGF-induced PKCα translocation to the plasma membrane, a process that correlates with PKC activity (26), was investigated next. Crude membrane and cytosolic fractions from VEGF-stimulated HUVECs were separated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Treatment of serum-starved HUVECs with VEGF resulted in the translocation of PKCα to the membrane fraction (Fig. 5D). This effect was suppressed by preincubating the cells with SN-6 (10 μm) or SEA0400 (1 μm) prior to VEGF stimulation (Fig. 5D). Thus, our findings are consistent with PKCα being the main Ca2+-sensitive intermediary linking reverse mode NCX activity to VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation.

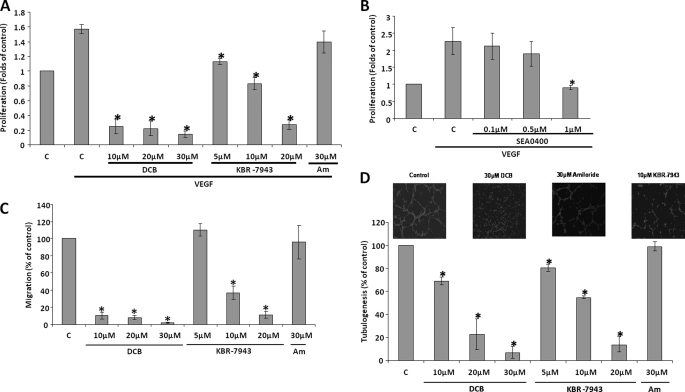

Effects of Reverse Mode NCX Inhibitors on HUVEC Proliferation

HUVECs were challenged with VEGF for 48 h in MCDB-131 medium in the presence of various concentrations of inhibitors (Fig. 6A). VEGF stimulation resulted in an ∼2-fold increase in the number of viable cells in comparison to the untreated controls, in agreement with a previous study (37). DCB had a significant impact on HUVEC proliferation because 10 μm DCB reduced HUVEC proliferation to ∼20% of the vehicle-treated control (0.1% v/v Me2SO); 20 or 30 μm DCB did not produce a further reduction. Additionally, 5 μm KBR-7943 reduced HUVEC proliferation to levels similar to the untreated control, and 10 μm KBR-7943 had a more pronounced effect. 20 μm KBR reduced the number of viable cells to similar levels as DCB. On the other hand, application of 30 μm amiloride had no statistically significant effect on VEGF-induced HUVEC proliferation. SN-6 could not be applied in this assay because in our hands it was not soluble in the MCDB-131 medium, and attempts to resuspend the compound by heating at 37 °C and sonication resulted in loss of activity (not shown). KBR-7943 and DCB are known to have off target effects at concentrations close to those that inhibit reverse mode NCX (34). As a result, the more potent and specific reverse mode NCX inhibitor SEA0400 (33) was used in the proliferation assay. SEA0400 at 1 μm reduced HUVEC proliferation to the levels of the unstimulated controls (0.86 ± 0.07, p = 0.046, n = 3) after 48 h of exposure to VEGF (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of NCX inhibitors on angiogenesis functional assays. A, HUVECs were exposed to VEGF (50 ng/ml) for 48 h in the presence of the indicated concentrations of DCB and KBR-7943, in MCDB-131 containing 0.1%w/v BSA. Bar C, control; bar Am, amiloride. The number of viable cells was determined using an alkaline phosphatase assay. The absorbance of the control sample (no VEGF stimulation) is arbitrarily set as 1. The bars represent the means ± S.E. from four independent experiments in triplicate. *, p < 0.05 versus the control. B, the effect of SEA0400 on HUVEC proliferation was determined as in A (n = 3). C, HUVEC migration toward VEGF was assessed in a FluoroblokTM assay in the presence of the indicated concentrations of DCB, KBR-7943, or amiloride, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” 50 ng/ml VEGF was used as a chemoattractant in the lower chamber. Bar C, control (0.1% v/v Me2SO); bar Am, amiloride. After 16 h, the migrated cells were fixed with 4% w/v paraformaldehyde and quantified. The mean number of migrating cells in the control wells is arbitrarily set at 100%. The bars represent the means ± S.E. from three independent experiments in duplicate. *, p < 0.05 versus the control. D, HUVECs (prelabeled with CellTracker green) were seeded in 24-well plates precoated with MatrigelTM in the presence of the indicated concentrations of DCB, KBR-7943, or amiloride in complete medium. Bar C, control (0.1% v/v Me2SO); bar Am, amiloride. The images were obtained after 3 h with an inverted fluorescent microscope and tubule lengths quantified with ImagePro software. The mean tubule length in control (C) wells is arbitrarily set at 100%. The bars represent the means ± S.E. from three independent experiments in duplicate. *, p < 0.05 versus the control. Representative images are shown in the inset, as indicated.

Effect of NCX Inhibitors on HUVEC Chemomigration

The involvement of NCX activity in HUVEC chemomigration toward VEGF was investigated. In FluroblokTM assays, DCB (10–30 μm) significantly reduced HUVEC migration toward VEGF to less than 10% of the vehicle-treated controls (0.1% v/v Me2SO; Fig. 6C). KBR-7943 also had a dose-dependent inhibitory effect: 5 μm KRB-7943 had no detectable effect, whereas 10 μm reduced migration to 37.1 ± 7.8% of the controls (p = 0.007, n = 3), and 20 μm decreased the number of migrating cells further to levels similar to DCB treatment (Fig. 6C). Again, amiloride had no apparent effect on the HUVEC chemotactic migration remaining at 95.9 ± 19.5% of the control value (p = 0.42, n = 3).

Effect of NCX Inhibitors on HUVEC Tubular Differentiation

HUVEC differentiation on Matrigel was disrupted by 10 μm DCB (69 ± 3.4%, p = 0.006, n = 3), whereas 20 μm-30 μm DCB almost completely abolished tubule formation (Fig. 6D). Similarly, KBR-7943 reduced tubule length in a dose-dependent manner; 5 μm KRB-7943 reduced tubulogenesis to 80.7 ± 3.6% of controls (p = 0.01, n = 3), 10 μm KRB-7943 produced a further reduction to 55.0 ± 1.5% (p < 0.001, n = 3), and 20 μm KBR-7943 almost completely abolished tubule formation. Importantly, again, amiloride had no apparent effect on HUVEC tubular differentiation (99.1 ± 3.8, p = 0.42, n = 3). Representative images of the tubulogenesis assay are shown in the inset of Fig. 6D.

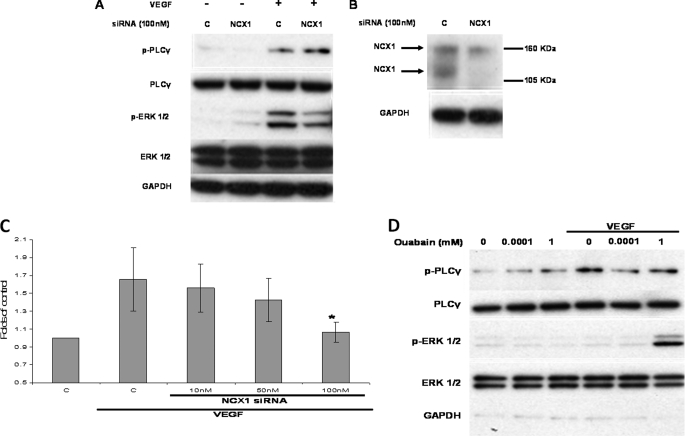

siRNA-mediated Knockdown of NCX1 Attenuated VEGF-induced ERK1/2 Phosphorylation and HUVEC Proliferation

No pharmacological inhibitors, including those used here (38, 39), are entirely specific for their target. Therefore, siRNA was employed to knock down the protein expression of NCX1, the predominant isoform in ECs (21), to complement the pharmacological data. In HUVECs transfected with NCX1-targeting siRNA, ERK1/2 phosphorylation in response to VEGF stimulation was reduced significantly in comparison with cells treated with nontargeting siRNA (14.3 ± 0.9-fold down to 5.7 ± 0.3 compared with unstimulated controls, p = 0.003, n = 3; Fig. 7A and supplemental Fig. S9). On the other hand, levels of phospho-PLCγ were similar (supplemental Fig. S9), suggesting that knockdown of NCX1 protein did not affect VEGFR2 kinase activity and that the cells were equally stimulated. Knockdown was confirmed by Western blot (Fig. 7B). The antibody recognized two bands with apparent molecular masses of ∼120 and 160 kDa in agreement with a previous study (21). Importantly, NCX1 knockdown suppressed VEGF-induced HUVEC proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of NCX siRNA on phospho-ERK1/2 and HUVEC proliferation. A, HUVECs transfected with control nontargeting siRNA or NCX1 targeting siRNA (100 nm for 48 h) were serum-starved and subsequently challenged with VEGF (50 ng/ml) for 10 min. ERK1/2 and PLCγ phosphorylation were determined as described for Fig. 1 (n = 3). B, in a parallel experiment NCX1 was immunoprecipitated from 500 μg of control or NCX1 siRNA-treated HUVECs (48 h). NCX1 knockdown was monitored by Western blot, and protein loading was demonstrated by GAPDH expression of the input cell lysates prior to immunoprecipitation (n = 3). C, HUVECs, transfected with NCX1-siRNA or control siRNA were exposed to VEGF (50 ng/ml) for 48 h, and proliferation was determined as in Fig. 6A. Bar C, control. The absorbance of the control sample (no VEGF stimulation) is arbitrarily set as 1. The bars represent the means ± S.E. from three independent experiments in triplicate. *, p < 0.05 versus the control. D, serum-starved HUVECs were pretreated with 100 nm or 1 mm of the Na+-K+ ATPase inhibitor ouabain for 1 min prior to application of VEGF (50 ng/ml) for 2 min. ERK1/2 and PLCγ phosphorylation was determined by Western blot. A representative immunoblot of three repeats is shown.

Inhibition of the Na+-K+-ATPase by Ouabain-augmented VEGF-induced ERK1/2 Phosphorylation

Treatment with high micromolar concentrations of ouabain is known to increase rapidly (within 1–3 min) [Na+]i and enhance reverse mode NCX in HUVECs (24). On the other hand, nanomolar concentrations of ouabain have been shown to activate ERK1/2 in rat renal epithelial cells (44) or neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (40) independently of changes in Na+ or Ca2+ through a mechanism that involves protein tyrosine phosphorylation (41). HUVECs were incubated with 100 nm or 1 mm ouabain for 1 min prior to the addition of VEGF. Neither concentration produced any obvious effect on ERK1/2 or PLCγ phosphorylation in the absence of VEGF for the 3-min duration of the experiment (Fig. 7D). Similarly, under control and 100 nm ouabain-pretreated conditions, brief (2 min) stimulation with VEGF did not induce any detectable ERK1/2 phosphorylation. However, following pretreatment with 1 mm ouabain, the phospho-ERK1/2 levels produced by similar (2 min) treatment with VEGF were increased (Fig. 7D). Thus, pretreatment of HUVECs with concentrations of ouabain that are known to inhibit the Na+ pump and increase [Na+]i in HUVECs (24) enhanced VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation, presumably by promoting reverse mode NCX activity.

DISCUSSION

Although the NCX can operate in reverse mode (24) and impact cellular functions such as NO production or Ca2+ influx in HUVECs (22), the role of NCX activity in VEGF signaling and angiogenic functions have not previously been investigated. Our main findings are as follows: (i) extracellular Na+ and Ca2+ are required for ERK1/2 phosphorylation in response to VEGF, and intracellular Ca2+ release is not sufficient; (ii) reverse mode NCX activity influences VEGF-induced Ca2+ transients and ERK1/2 activation via the PKCα-B-Raf pathway; and (iii) reverse mode NCX plays a significant role in HUVEC proliferation, chemomigration, and tubular differentiation.

Role of Extracellular Ca2+ in VEGF-induced ERK1/2 Phosphorylation

Our explicit assumption that influx of Ca2+ is required for ERK1/2 phosphorylation by VEGF was confirmed because this was abrogated in a nominal Ca2+-free physiological medium (Fig. 1A). The sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase inhibitor TG increased the initial phase of the HUVEC Ca2+ transient to a similar extent irrespective of the presence of extracellular Ca2+, because of leakage of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (42). However, TG alone failed to increase levels of phospho-ERK1/2 or phospho-PLCγ. On the other hand, when VEGF was added 2 min after TG pretreatment at the peak of the Ca2+ response, ERK1/2 phosphorylation was induced only in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 2B). In mast cells, TG induces ERK1/2 phosphorylation via activation of Ca2+ release-activated channels (43). This apparent discrepancy is not surprising, because Ca2+ is known to elicit different responses depending on the cell type (44). For example, in fibroblasts, increasing [Ca2+]i inhibited, while buffering of intracellular Ca2+ augmented EGF-induced phospho-ERK1/2 (45). Thus, we infer that Ca2+ influx rather than internal release, is essential for VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation in EC.

Role of Extracellular Na+ in VEGF-induced ERK1/2 Phosphorylation

Reduction of extracellular [Na+] 10-fold by isotonic substitution substantially decreased VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 1B). Complete removal of extracellular Na+ results in reverse mode NCX activity in cardiomyocytes and heterologous systems (11). This appears to contradict our proposal that reverse mode NCX is required for ERK1/2 phosphorylation by VEGF. However, the effects of extracellular Na+ on NCX activity in intact ECs are expected to be complex. VEGF initially depolarizes HUVECs (23, 46) and conversely removal of extracellular Na+ can hyperpolarize them (24). Membrane hyperpolarization would antagonize the drive for reverse mode NCX. Thus, it is plausible, that in our system reduction of extracellular [Na+] could inhibit reverse mode NCX. In addition, in neuronal slices (47), cardiomyocytes (48), and smooth muscle cells (49), reverse mode NCX has been linked to a Na+ influx pathway, promoting the reversal of the exchanger by increasing [Na+]i. Removal of extracellular Na+ should suppress such potentially associated mechanisms. Indeed, inhibitory concentrations of ouabain substantially enhanced VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation, as expected if reverse mode NCX was involved (Fig. 7D). This agrees with observations in parotid acinar cells where, although pretreatment with ouabain failed to activate ERK1/2, it substantially enhanced carbacol-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (50, 51). In cardiomyocytes, NCX is required for the Na+-K+-ATPase inhibitory effects to manifest (38). Taken together, our experiments suggest that transmembrane [Na+] plays a significant role in ERK1/2 activation, at least partially by regulating the mode of NCX activity. Further work is required to identify putative Na+ entry pathway(s) in ECs.

Effect of NCX Inhibitors on VEGF-induced ERK1/2 Phosphorylation and [Ca2+]i Transients

A panel of forward and reverse mode NCX inhibitors suppressed VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a dose- (Fig. 3, B–E) and time-dependent manner (Fig. 3A and supplemental Figs. S7 and S8). Importantly, under all conditions, phospho-PLCγTyr-783 levels remained unaffected. PLCγ is directly phosphorylated by VEGFR2 (4). Thus, VEGFR2 activity appeared to be unchanged by NCX inhibition. Additionally, because PLCγTyr783 correlates with activity (52), it can be inferred that similar to VGSC (23), NCX activity inhibits the pathway leading to ERK1/2 phosphorylation downstream of PLCγ.

In nonexcitable cells, agonist-induced Ca2+ responses consist of an initial transient (phasic) element, attributed to Ca2+ release from internal stores and a sustained (tonic) response attributed to Ca2+ influx (53). VEGF-activated ECs exhibited biphasic Ca2+ transients (23, 46) and an increase in [Ca2+]i is essential for VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (23). Preincubation of HUVECs with NCX inhibitors KBR-7943 (Fig. 4A), SN-6 (Fig. 4B) or SEA0400 (Fig. 4C) before VEGF stimulation resulted in modest inhibition of the transient Ca2+ response and partially suppressed the sustained component (Fig. 4D). Thus, reverse mode NCX could partially influence agonist-induced Ca2+ transients, as in smooth muscle cells (49, 54). Although NCX inhibition does not completely abolish the sustained Ca2+ response, this is not surprising, because a number of receptor- or store-operated channels have been implicated in regulating Ca2+ influx in ECs (55, 56). Nevertheless, it would appear that reverse mode NCX provides at least a proportion of the essential Ca2+ signal required for VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation.

Role of PKCα

We previously reported that VGSC activity influences VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation through Ca2+-sensitive PKCα (23). PKCα is involved in angiogenesis via stimulation of EC proliferation, migration, and tubular differentiation in vitro and in vivo (57–59). Thus, the effect of reverse mode NCX activity on PKCα activity was investigated using three complementary approaches. NCX inhibitors attenuated B-Raf activity (Fig. 5A), which is downstream of PKC in a number of systems (60) including ECs (35). Also, in an in situ PKC activity assay, inhibitors of reverse mode NCX activity diminished the PKC-dependent phosphorylation of a peptide pseudosubstrate (Fig. 5B). Moreover, SN-6 and SEA0400 suppressed VEGF-induced PKCα translocation to the plasma membrane fraction (Fig. 5C), a process that correlates with PKCα activation (26). Thus, we propose that PKCα is the Ca2+-sensitive enzyme, influenced by reverse mode NCX, linking VEGFR-2 ligation with ERK1/2 activation.

The Role of NCX in HUVEC Functional Assays

Inhibition of NCX activity with KBR-7943 and DCB significantly reduced VEGF-induced HUVEC proliferation (Fig. 6A). However, these agents can also inhibit additional ionic fluxes (31), and in cardiomyocytes the inhibition of forward mode NCX resulted in cytotoxicity (11). Because 10–30 μm DCB reduced the number of viable cells, the apparent decrease in HUVEC proliferation could be at least partially due to cytotoxic effects of inhibition of forward mode NCX.

Although KBR-7943 (up to 30 μm) reportedly has a minimal acute effect on NCX forward mode activity (31), it cannot be assumed that longer exposure would also be inactive because KBR-7943 gave reductions in HUVEC viability similar to DCB. Consequently, the assays where cells were exposed from 3 to 48 h to DCB or high concentrations of KBR7943 (20 μm) should be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, with the highly specific reverse mode NCX inhibitor SEA0400 (33), significant attenuation of HUVEC proliferation in response to VEGF was seen in the absence of any effects on viability (Fig. 6B).

NCX inhibitors suppressed HUVEC migration toward VEGF (Fig. 6C), a process crucial for neoangiogenesis (61) and requiring PKCα activity (59). The same NCX inhibitors also attenuated HUVEC tubular differentiation on extracellular matrices (Fig. 6D). Because PKCα (57) and ERK1/2 (62) are required for HUVEC tubular differentiation, these results provide further evidence that inhibition of NCX activity has potentially significant functional consequences on angiogenesis, at least in vitro.

Knockdown of NCX with siRNA

Knockdown of NCX1 (which will of course reduce both forward and reverse modes of action) attenuated VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 7A) and suppressed VEGF-induced proliferation (Fig. 7C), without reducing cell viability. Consequently, the reduction of HUVEC proliferation by NCX1 siRNA can be attributed to the attenuation of ERK1/2 signaling, rather than cell death.

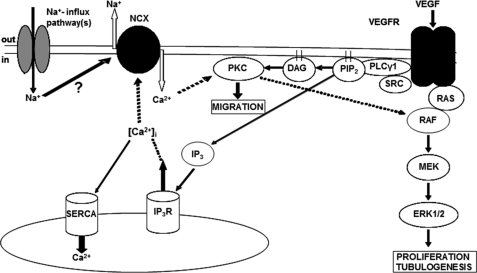

Concluding Remarks and Proposed Mechanistic Model

To summarize, the major finding of our study is that Ca2+ influx though reverse mode NCX is a crucial modulator of VEGF signaling through the PKCα-B-Raf-ERK1/2 axis and thereby the angiogenic properties of HUVECs in vitro. These results are consistent with the following model (Fig. 8): ligation of VEGFR leads to activation of PLCγ and the generation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and DAG. Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate releases Ca2+ from internal stores, increasing [Ca2+]i and activating NCX. Ca2+ influx through reverse mode NCX then targets PKCα to the plasma membrane where, through its association with DAG, it becomes fully activated. In turn, PKCα activates Raf through a Ras-independent mechanism resulting in ERK1/2 phosphorylation, ultimately enhancing HUVEC proliferation, migration, and tubular differentiation. Regulation of the membrane potential by VGSCs (23) and potentially associated Na+ influx mechanism(s) could provide further degrees of regulation of reverse NCX and fine-tune the HUVEC response to VEGF.

FIGURE 8.

Proposed mechanism of reverse mode NCX involvement in VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Bold lines show direct interactions. Dashed lines show indirect interactions. Activation of PLCγ downstream of VEGFR leads to the generation of diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3). Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate leads to Ca2+ release from the internal stores activating the NCX. Ca2+ influx through the exchanger targets PKCα to the plasma membrane and ultimately results in ERK1/2 activation. IP3R, inositol triphosphate receptor; SERCA, sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase.

As this study was submitted, Li et al. (63) reported that inhibition of the Ca2+ release-activated channel Orai1 suppressed VEGF-induced Ca2+ entry and EC angiogenesis, although the effects on downstream signaling were not investigated. Given the importance of Ca2+ influx on VEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (23) (Fig. 1A), the effect of Orai1 suppression on phospho-ERK1/2 merits further investigation. It is conceivable that Ca2+ influx through reverse mode NCX regulates short term EC responses to VEGF, whereas influx through Orai1 could affect longer term responses through loading of internal Ca2+ stores. Nonetheless, the report of Li et al., in agreement with our work, highlights the importance of Ca2+ influx in angiogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the members of the Tumour Biology and Metastasis Team, Cancer Research UK Cancer Therapeutics Unit at the Institute of Cancer Research for scientific input throughout this project.

This work was supported by British Heart Foundation Studentship FS/06/22 (to P. A.) and by National Health Service funding to the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S9.

- EC

- endothelial cell

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- NCX

- Na+-Ca2+ exchanger

- PLCγ1

- phospholipase Cγ1

- TG

- thapsigargin

- VGSC

- voltage-gated sodium channels

- DCB

- 3′, 4′-dichlorobenzamil

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- GFX

- GF109293X

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinases

- NO

- nitric oxide

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- TCA

- trichloroacetic acid

- VGSC

- voltage-gated sodium channel.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chung A. S., Lee J., Ferrara N. (2010) Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 505–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adams R. H., Alitalo K. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 464–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olsson A. K., Dimberg A., Kreuger J., Claesson-Welsh L. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 359–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takahashi T., Yamaguchi S., Chida K., Shibuya M. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 2768–2778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gerber H. P., McMurtrey A., Kowalski J., Yan M., Keyt B. A., Dixit V., Ferrara N. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 30336–30343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heath V. L., Bicknell R. (2009) Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 6, 395–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferrara N. (2010) Nat. Med. 16, 1107–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crawford Y., Ferrara N. (2009) Cell Tissue Res. 335, 261–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kerbel R. S. (2008) N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 2039–2049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bergers G., Hanahan D. (2008) Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 592–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blaustein M. P., Lederer W. J. (1999) Physiol. Rev. 79, 763–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lytton J. (2007) Biochem. J. 406, 365–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reeves J. P., Hale C. C. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 7733–7739 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crespo L. M., Grantham C. J., Cannell M. B. (1990) Nature 345, 618–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matsuoka S., Hilgemann D. W. (1992) J. Gen. Physiol. 100, 963–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fujioka Y., Komeda M., Matsuoka S. (2000) J. Physiol. 523, 339–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sage S. O., van Breemen C., Cannell M. B. (1991) J. Physiol. 440, 569–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Juhaszova M., Ambesi A., Lindenmayer G. E., Bloch R. J., Blaustein M. P. (1994) Am. J. Physiol. 266, C234–C242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li L., van Breemen C. (1995) Circ. Res. 76, 396–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sedova M., Blatter L. A. (1999) Cell Calcium 25, 333–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Szewczyk M. M., Davis K. A., Samson S. E., Simpson F., Rangachari P. K., Grover A. K. (2007) J. Cell Mol. Med. 11, 129–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Teubl M., Groschner K., Kohlwein S. D., Mayer B., Schmidt K. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 29529–29535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andrikopoulos P., Fraser S. P., Patterson L., Ahmad Z., Burcu H., Ottaviani D., Diss J. K., Box C., Eccles S. A., Djamgoz M. B. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16846–16860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liang G. H., Kim M. Y., Park S., Kim J. A., Choi S., Suh S. H. (2008) Pflugers Arch. 457, 67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heasley L. E., Johnson G. L. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 8646–8652 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xia P., Aiello L. P., Ishii H., Jiang Z. Y., Park D. J., Robinson G. S., Takagi H., Newsome W. P., Jirousek M. R., King G. L. (1996) J. Clin. Invest. 98, 2018–2026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eccles S. A., Court W., Patterson L., Sanderson S. (2009) Methods Mol. Biol. 467, 159–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jones N. P., Peak J., Brader S., Eccles S. A., Katan M. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118, 2695–2706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fleming I., Fisslthaler B., Busse R. (1995) Circ. Res. 76, 522–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kleyman T. R., Cragoe E. J., Jr. (1990) Methods Enzymol. 191, 739–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Watano T., Kimura J., Morita T., Nakanishi H. (1996) Br. J. Pharmacol. 119, 555–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Iwamoto T., Inoue Y., Ito K., Sakaue T., Kita S., Katsuragi T. (2004) Mol. Pharmacol. 66, 45–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matsuda T., Arakawa N., Takuma K., Kishida Y., Kawasaki Y., Sakaue M., Takahashi K., Takahashi T., Suzuki T., Ota T., Hamano-Takahashi A., Onishi M., Tanaka Y, Kameo K., Baba A. (2001) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 298, 249–256 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Watanabe Y., Koide Y., Kimura J. (2006) J. Pharmacol. Sci. 102, 7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Takahashi T., Ueno H., Shibuya M. (1999) Oncogene 18, 2221–2230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Doanes A. M., Hegland D. D., Sethi R., Kovesdi I., Bruder J. T., Finkel T. (1999) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 255, 545–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zeng H., Sanyal S., Mukhopadhyay D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 32714–32719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reuter H., Henderson S. A., Han T., Matsuda T., Baba A., Ross R. S., Goldhaber J. I., Philipson K. D. (2002) Circ. Res. 91, 90–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ozdemir S., Bito V., Holemans P., Vinet L., Mercadier J. J., Varro A., Sipido K. R. (2008) Circ. Res. 102, 1398–1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dmitrieva R. I., Doris P. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28160–28166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu J., Tian J., Haas M., Shapiro J. I., Askari A., Xie Z. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27838–27844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Putney J. W., Jr. (2001) Mol. Interv. 1, 84–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chang W. C., Nelson C., Parekh A. B. (2006) FASEB J. 20, 2381–2383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Berridge M. J., Bootman M. D., Roderick H. L. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 517–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cook S. J., Beltman J., Cadwallader K. A., McMahon M., McCormick F. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 13309–13319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dawson N. S., Zawieja D. C., Wu M. H., Granger H. J. (2006) FASEB J. 20, 991–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Platel J. C., Boisseau S., Dupuis A., Brocard J., Poupard A., Savasta M., Villaz M., Albrieux M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 19174–19179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Eder P., Probst D., Rosker C., Poteser M., Wolinski H., Kohlwein S. D., Romanin C., Groschner K. (2007) Cardiovasc. Res. 73, 111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Poburko D., Liao C. H., Lemos V. S., Lin E., Maruyama Y., Cole W. C., van Breemen C. (2007) Circ. Res. 101, 1030–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Plourde D., Soltoff S. P. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 290, C702–C710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Soltoff S. P., Hedden L. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 295, C588–C589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Singer W. D., Brown H. A., Sternweis P. C. (1997) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66, 475–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Parekh A. B., Putney J. W., Jr. (2005) Physiol. Rev. 85, 757–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lemos V. S., Poburko D., Liao C. H., Cole W. C., van Breemen C. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 352, 130–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Abdullaev I. F., Bisaillon J. M., Potier M., Gonzalez J. C., Motiani R. K., Trebak M. (2008) Circ. Res. 103, 1289–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nilius B., Droogmans G. (2001) Physiol. Rev. 81, 1415–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xu H., Czerwinski P., Hortmann M., Sohn H. Y., Förstermann U., Li H. (2008) Cardiovasc. Res. 78, 349–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wong C., Jin Z. G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33262–33269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang A., Nomura M., Patan S., Ware J. A. (2002) Circ. Res. 90, 609–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Marais R., Light Y., Mason C., Paterson H., Olson M. F., Marshall C. J. (1998) Science 280, 109–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lamalice L., Le Boeuf F., Huot J. (2007) Circ. Res. 100, 782–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mavria G., Vercoulen Y., Yeo M., Paterson H., Karasarides M., Marais R., Bird D., Marshall C. J. (2006) Cancer Cell 9, 33–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Li J., Cubbon R. M., Wilson L. A., Amer M. S., McKeown L., Hou B., Majeed Y., Tumova S., Seymour V. A., Taylor H., Stacey M., O'Regan D., Foster R., Porter K. E., Kearney M. T., Beech D. J. (2011) Circ. Res. 108, 1190–1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.